The Varda Vue in California: The Poetics of Cinema in Mur murs & Documenteur

by: Mathias Barkhausen , November 7, 2023

by: Mathias Barkhausen , November 7, 2023

Introduction

‘I always make a distinction between fiction and documentary,’ Agnès Varda asserted during an audience discussion at the Cinémathèque Française in January 2019. Those familiar with her work may shake their heads in disbelief, as she had spoken of seeing her filmmaking as subjective documentary filmmaking before (Westley 2006). This designation may seem an appropriate description for films such as Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès, 2019), Visages Villages (Faces, Places, 2017) or Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I, 2001), but it is more unruly when looking at her late short films. In Le lion volatil (2003), a lion statue comes to life and then disappears; in Les 3 boutons (2015) a young woman is given a magical dress by her postman, through which she then experiences the world anew. In these films, fantastic elements break into Varda’s cinematic worlds and breathe magic into the everyday, as it does in her documentaries Daguerréotypes (1975) and Mur murs (1981). How are Varda’s contrasting statements to be evaluated? Is there a way to reconcile their contradictions? My essay will deal with precisely these questions. How can Varda’s idiosyncratic poetics be described, what poetological programme should we identify? Where in her work do we find the boundaries of documentary, where those of fiction? I will concentrate on two of her lesser-known films to find my answers.

Mur murs and Documenteur (1981) are feature-length films made at the beginning of the 1980s. Their common subject is life in Los Angeles, but they differ significantly in conceptual approach. While Mur murs is dedicated to the Chicano neighbourhoods and the lives of the African-American population represented in a series of murals, Documenteur shows the character Emilie (Sabine Mamou) and her son Martin (Mathieu Demy) trying to gain a foothold in the city. Discussing these two films, Serge Daney claimed that ‘All good documentarists position themselves between fiction and documentary in the zone of the virtual’ (2000: 114). In what follows I discuss them as two sides of the same coin, both conceptually and thematically.

Mur Murs: If These Walls Could Talk

The very title of Mur murs tells us what to expect. It is a play on words between French and English in which ‘mur’ (singular) and ‘murs’ (plural) mean ‘wall/ walls,’ but together they make up the word ‘murmurs,’ whispering. Walls whisper. It seems to play with the expression ‘If these walls could talk.’ The film begins in the dark with a few bars from a Spanish-language children’s song before the picture opens with a boy in front of a painted and graffitied wall. The title of the opening credits announces Mur murs, a film by Agnès Varda, made, as stated in brackets, in ‘Los Angeles 1980.’ The credits are superimposed from left to right. The boy walks with one hand on the wall, opening the film as a master of ceremonies opens a curtain.

This shot achieves several things. The title clearly announces the film as the work of the auteur ‘Varda.’ [1] However it also, to an extent, asserts the city Los Angeles as co-author. The reference not only serves as a topographical and temporal classification but also points to a collaborative process. The attribution of the film to the documentarian as its controlling authority is countered by the presence of the city, not as a large settlement administered under the name ‘Los Angeles’ but rather as a social structure that shows itself in images. On an enunciative level, the credits provide instructions (through the absence of actors’ names and the intertitle ‘realisé et commenté par Agnès Varda’ [directed and commented by Agnès Varda]) to read the film as a documentary, made without a script and presented by ‘Varda’ with an external commentary. Varda is thus the instance that cinematically accesses Los Angeles as a reality, while ‘Varda’ vouches for the presentation of the images and lays out the creative process in a poetic commentary. This commentary lists a variety of tourist activities undertaken by a visitor to Los Angeles, but then the voice interjects: ‘As for me, I mostly saw walls. Graffiti-covered walls, as beautiful as paintings … This was the beginning of a surprising and joyful discovery … They are living, breathing, seething walls; and talking, wailing, murmuring walls.’ [2]

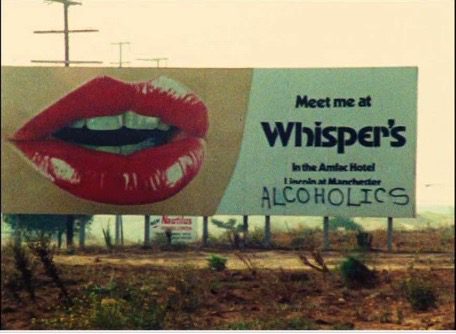

Even as Varda summarises what she has seen, the camera still shows a wall, which can thus be understood as an impersonal counterpart to the personal commentary. This static image suggests a technomorphic camera, a camera that embodies the director herself. Its controlled camerawork is maintained in large sections of the film and strives to create an intersubjectivity which balances personal commentary with impersonal technology. As the commentary continues it suggests an opposition between this intersubjectivity and a commercialised gaze: billboards on highways are juxtaposed with the titular murals (Figs. 1 & 2).

Fig. 1: Mur Murs, TC 02:57.

Fig. 1: Mur Murs, TC 02:57.

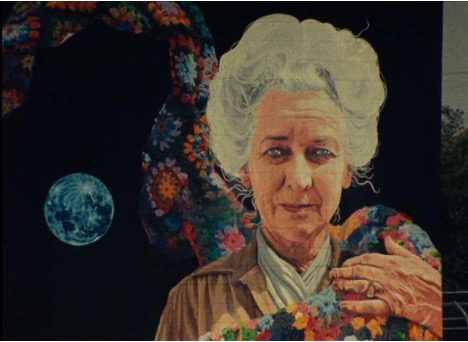

Fig 2: Mur Murs, TC 03:11.

Fig 2: Mur Murs, TC 03:11.

The aesthetic values of the murals are juxtaposed with the commercial interests of the soulless, mendacious posters: Fig.1’s promise of whispering is fulfilled in the murals’ authenticity. There is also a sonic change: guitar riffs give way to cheerful flute music, marking a transition in the image of Los Angeles presented by the film, but also imbuing it with a progressive rhythm and energy. The montage offers a paratactic sequence of different walls. On an affective level, we settle into the music and the colourful paintings even as the gallery of images prevents the formation of an orthodox cause-effect narration. In the course of this montage, the film dispenses with Varda’s commentary and allows the murals literally and figuratively to speak for themselves. They murmur the names of their creators, an effect which functions both as an index for the artist—’Herron was here’—and as a corrective mimesis for Los Angeles as image, emphasising that these murals show both what Los Angeles might be and what it really is: a city not of the rich and famous but of ordinary people.

The juxtaposition of murals can be understood as a democratising process: the montage places painted human faces next to one another in an egalitarian manner. This is not a filmmaker coming in from the outside to provide explanations or to contextualise this art in its relation to other traditions of painting; these pictures stand side by side on an equal footing. In contrast to the advertising billboards, they are anthropomorphised, in multiple senses. The terms ‘anthropos’ (human) and ‘morphē ‘(form, shape) combine to emphasise both that the paintings are forms given by human beings and that they themselves possess human-like qualities through their whispering.

The murmur of the walls not only seems mysterious but is also taken for granted by the voiceover as if there is no need to explain why walls are speaking. This nonchalant integration of an element of fantasy into the film’s realistic register can be seen as in the literary tradition of magical realism, a popular genre in Latin America, in which the boundaries of everyday life are occasionally transgressed with fantastic elements. This intrusion of the magical into the world of the everyday is negotiated as a matter of course (Brunner/ Hüningen 2011). Accessing this genre in the context of contemporary Los Angeles is not an arbitrary choice. It needs to be understood in the context of these portraits of Californian Chicano culture.

The commentary resumes after a short pause, provoking a break within the film’s presentation of its own authorship. While ‘Varda’ talks about travelling west to east, Varda’s handheld tracking shot captured from a moving car shows the light falling between an avenue of palm trees. The result is a play with the distance between the filmmaker and the filmed, a game the film continues to play. At times, it seems to be Varda’s camera-eye, at others it is the creation of an impersonal visual record. Mur murs is thus a documentary that understands itself as a form of art and formulates a claim to being artful, portraying the painters of the murals and other artists as well as finding indirect analogies between the murals and the cinema screen. Its first protagonist is an English photographer in Venice Beach, who fulfils a mirror function to the director. He is seen on roller skates taking photos which are shown on the screen. He claims that his interest is to show moving people in front of the murals. Of course, by definition, photography does not or cannot show movement, but this film image captures both: a camera pans through the area in which the photographer is working. What is thematised is a reversal of medium specificity and the object of representation. As a static medium, photography freezes fleeting moments of human movement, while the moving film places the static walls in their relation to the moving inhabitants. The encounter encompasses not only the meeting of two people but also that of human and artwork, and artwork and artwork. Analogous to the inclusion of the paintings at the beginning, the film unfolds a juxtaposition of realities. The Los Angeles of Mur murs is characterised by street gangs, racism, street music and the everyday hustle and bustle that finds expression in the painting, which is itself part of everyday life. The encounter includes both planned and spontaneous interactions: as we look at the painting of a second artist, a parade with horses moves through the street. Instead of breaking off the shot, the film reflects on this moment and uses it as an element of dynamism, both in its depiction of everyday life in LA and as a transition to the artworks that follow. This spontaneity of recording and research, as Delphine Bénézet puts it, ‘directs the spectator’s attention to the tentative quality of the film’ (Bénézet 2014: 76). It also strives for authenticity by laying the filming situation open.

Bénézet speaks of Mur murs as a ‘vibrant patchwork of scenes and locations’ (Bénézet 2009: 87). I would add, of course, voices. The amalgam of voices and images results in a polyphony in which artists are interviewed in front of their respective artwork. Varda develops this communicative situation into a combination of ‘I speak to you about me and my art’ and ‘I show you what they say about themselves and their art.’ In this respect, Mur murs is an attempt to reflect both on the communicative conditions of documentary filmmaking and on the media within which that communication takes place.

Murals & Film as Artforms of Visibility

In historically Black neighbourhoods, Varda’s team encounters murals by Black artists before turning to the street gang tags of Chicano neighbourhoods. Interviews with individual members of these groups encourage us to associate ‘Varda’ with an ethno- and sociographic interest in the lifestyles of marginalised people. People are arranged in front of paintings as if they were part of them, as well as in front of houses and objects. The approach of letting marginalised groups speak for themselves is diametrically opposed to that of dominant US mass media and politics in the 1970s, which might be described more as ‘I tell you about them’. This approach shifts away from dominant discourse about these groups, towards the creation of something like a counter public. For example, the film draws attention to the community-building element of gang violence. The gang markings of who and what belongs to whom are transferred from the walls to the bodies of the members, which ‘Varda’ refers to also as murals. These body murals are anthropomorphic in the sense that they give shape to people and their lives.

However, rather than indulging in an idealisation of the gangs, the film records a found moment in which a street musician comments on their behaviour. ‘Why are we burning ourselves?’ he sings, but his song also offers an answer: ‘What we need is unity.’ ‘Varda’ points out that the musician’s ethnic background is Hispanic, but he sings a blues melody: in these ethnically diverse neighbourhoods, the American myth of the melting pot is fulfilled.

Mur murs finds the answer to these questions where they arise: on the street. The song is not only a resident’s contribution to a discussion about gang crime: it shows how this discussion is condensed into an art form. Art in general, and here the murals in particular, provide access to an analysis of how society functions (Smith 1998: 62).

Murals & Mur murs: Familiar and Alien at Once

Murals in public spaces are easily accessible; the residents almost stumble over them. This moment of stumbling is intentional, as emphasised by one of the artists towards the end of the film. As he explains, he designs his paintings in such a way that they provoke the passers-by to stop—because the paintings are both realistic and strange.

This poetological agenda is close to the ostranenie of Russian Formalism, but it is also the defining aesthetic of Mur murs as a documentary. The alienation of what is experienced through the whispering wall, the targeted use of music, the performative dimension of the protagonists’ presence in the film, all provoke a sharpened eye for the everyday. The whispering voice in Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967) intends to whisper truths of universal validity; in Mur murs truth is fragmented and polyphonic as multiple voices from various locations speak out from within the structure of the film. The enunciation is characterised by fractures and contradictions from which the attribution of Mur murs as a documentary can arise, but which also approaches the essayistic. It circles around its subject matter and attempts to grasp it through the literal and metaphorical capture of many different voices. Bénézet characterises Varda’s approach as that of a cinéaste passeur, a ‘mediator between filmed subject and spectators, but also space and time and moment of screening’ (2014: 71). As cinéaste passeur, Varda curates a cinematic time capsule of different realities. Her voice can be located variously throughout the film. At times, it appears as a ‘present absence’ (Hartmann 2012: 152) when she speaks offscreen and thus becomes a social actor of the hors champs, structuring the moment of the recording (Hartmann 2012: 152). At others, her reflections have been recorded later and edited in. There is thus no single position from which the mediation takes place.

Sound design similarly makes it clear that ‘Varda’ refuses to adhere to documentary purity. Sound and image are not synchronised. The ironic inclusion of a pig’s grunt when filming the artwork Pig Paradise not only marks the artefactual status of the result but also creates the kind of distance that direct cinema had sought to overcome (Beyerle 1991: 29). The film repeats a game with the concepts of distance and proximity. This, as well as the low provocation of dramatic scenes, does not allow the film to be classified as cinéma vérité.

It is thus most appropriate to seek to characterise Varda’s method in Mur murs in its relation to other areas of her work. An empathetic view of the magic of everyday life and the hardships of ‘the little people’ can also be found in her documentary Daguerréotypes (1975), in which, alongside sober, realistic interview sequences, the director is portrayed as a magician of Paris’s Rue Daguerre. There is, too, a close relationship with her short film Black Panthers (1968), in which she deals with protests against the arrest of Huey Newton: in a mixture of poetic commentary and interview, she establishes a position of closeness to the protesters, but reflects on her outsider status as a white person. Mur murs can be seen against the background of the performative and group/auto-ethnographic documentaries that emerged in the mid-1980s, such as the work of Marlon Riggs (Tongues Untied, 1989) and Allie Light (Dialogues with Madwomen, 1994), where subject positions such as those of Black homosexual men or women experiencing mental ill health problems represent themselves in their own work–a mode of self-authorship which has affinities with but must be differentiated from Varda’s collaborative solidarity.

Of Mur murs we can thus say that Varda presents ‘Varda’ as an enunciator who strives for an effect of authenticity through personal experience. On one hand, the integration of obvious ‘handles’ into the life of the wall is part of a strategy of authentication in which fictional elements in non-fictional registers work towards the documentary effect (Fludeirnik, Falkenhayner & Steiner, 2015: 11). The whispering of the walls is not real, but it is truthful. On the other, her playful approach to the realities of people’s lives through their art is an attempt to use film to create a space for their experience. Technically, the mere documentation of what is ‘there’ reaches its limit at the inner life. But film-specific devices such as voice-over or non-synchronous sound can get past this to create an idea of life. In this respect, play between fiction and fact can be identified as the media-specific characteristics of the art form. The wall’s two-dimensionality resembles that of the cinema screen: both open up a three-dimensional, virtual space in which the ‘creative treatment of actuality’ (Grierson 1933: 7) can take place, be it in the form of larger-than-life faces or whispering objects. Walls, like cinema, are places of encounter, bringing together fantastic things and people as well as those taken from reality.

In the oscillation between closeness and distance, separation and self-incorporation of the documentarian, us and them, as well as the juxtaposition of the realistic and the fantastic, the film opens up a reflection on art as a collective experience that transcends ethnicities and national borders. Everything is worth recording and painting. Varda inscribes herself into this tradition: a photograph shows her playing ball with her son Mathieu Demy in front of a wall. It is the same wall with a similar visual motif with which the companion film Documenteur begins (Figs. 3 & 4):

Fig. 3: Mur murs, TC 1:17:40.

Fig 4: Documenteur, TC 00:43.

Documenteur: Lying Proofs?

They say that every ending has a beginning: the first shot of Documenteur breathes life into the last shot of Mur murs. In front of a wall, a woman and a boy are playing ball. On closer inspection, one does not recognise Agnès Varda or any well-known actress: it is Sabine Mamou, the editor of Mur murs. The credits title this second film Documenteur ‘an emotion picture by Agnès Varda.’ The title is then specified as an acronym of the words ‘dodo cucu maman vas-tu-te-taire,’ marking it as ‘un film de fiction.’ Rather than merely establishing the subject matter of what is filmed, the film formulates a statement about the film’s access to the visual. The title is in fact a portemanteau of the French words document (the document) and menteur (the liar). ‘Document’ is etymologically derived from the Latin documentus (the proof). Documenteur is, therefore, a lying proof–an oxymoron. What does one want to prove with a lie? The title is phonetically strikingly similar to the French term for documentary film, documentaire, as well as documentary filmmaker, documentaire again. To be more precise, the two words are a phonetic minimal pair–they differ by only a single sound. In the film as in language, this minimal change sets a shift in meaning in motion.

At a second glance, the syllables in the parenthetical addition to the title do not add up to the name of the work. Only the second part can be translated simply: ‘Shut up, Mama.’ In the case of ‘Dodo cucu,’ we have to approach it associatively. François Niney notes that the strongly didactic documentaries used in French school lessons were called ‘docucu’ (2012: 21). All in all, there is nevertheless no clear picture of how the title of the ‘emotion picture’ is to be understood. Perhaps it is a ‘Mama, shut up, stop lecturing me’? Maybe it is just a false trail?

These docucus are characterised by their explanatory commentary, so the film has been shot in what Bill Nichols calls the expository mode (Nichols 2001: 105-109). Contrasting this, an associative, poetic voice-over sets in, unmistakably attributable to ‘Varda.’ The image is subordinate to the commentary and follows it logically. As if in response to the proverb, ‘It is often said that when you are up against a wall is when you have to show your real face’ (Documenteur, TC 01:21-01:24), murals, as we saw in Mur murs, are edited together, images of people opening their mouths in an expressionist manner. But while the paintings in the previous film articulated the feelings of their creators, here they are those of the passers-by. The director’s voice provokes irritation with the reading instructions provided by the credits. This assertion of a ‘film de fiction’ sets in motion a diegetisation of the narrative instance. Where is the enunciation located? In the personal Varda, or the impersonal one that uses ‘Varda’ as a textual structure? At this point, the film shows no interest in dogmatically formulated rules of staging; it remains unclear if the voice can be located outside or inside the diegesis. The label ‘documenteur,’ which is to be considered a leitmotif, comments on the story that unfolds afterwards, establishing the interdependence of the fictional and the factual. Our knowledge of the factual dictates the rules of how the diegesis is to be constructed. The ball game is elevated to an asserted or possible reality, supported visually by the wall images already known from a viewing of Mur murs and therefore constructed as non-fictional. These images confer credibility on those of Documenteur. The most significant reading instruction, that of the title, thus loses a certain interpretive authority. Since fiction cannot be accused of lying (see Eitzen 1998), such a reproach to the film hardly holds up. Does the lie only emerge in the concatenation of fictional and non-fictional images? Whichever way one reads it, one can see Documenteur’s diegesis as closely related to an afilmic reality, an impression that is repeatedly undermined in what follows.

The painted faces on the walls are followed by human ones—mostly those of unkempt men. These too are cut paratactically, but the people turn and look directly into the camera. This gaze constitutes the registration of the recording situation on the part of those filmed: in the words of Karsten Witte, it provokes a denunciation of the fiction contract (1993: 29), though I would modify this description to an account of the permeability of the boundaries between fiction and documentation. This gaze into the camera reflexively refers back to enunciation (Metz 1997: 31); it addresses the viewer and marks the performative character of acting in front of the camera at this point. The extradiegetic voice-over then introduces the woman played by Sabine Mamou as the protagonist. ‘Varda’ explains, ‘that woman … she is mostly like me, and she is real. But I don’t recognise myself in that woman.’ The truth, or a lie?

A Study in Perspective

The woman can be understood as a mirror figure. The frame captures her looking at something beyond the right side of the picture before she turns her head and looks to the left. The spectacle clearly states that a gaze is being cast–in conventional film language, as the first element of a point-of-view structure before a second shot suggests what that gaze captures. In such cases, the point-of-view structure serves subjectification; it is an offer of empathy with the seeing character (Branigan 1984: 80). Documenteur refuses this standard expression of film language at this specific moment because when the character here looks to the left from her perspective, the camera pans to the right with her, instead of switching to a separate shot. The character surveys the surroundings with her gaze; the camera does the same but still has a different perspective. For Roger Odin, it is first the identification of the camera gaze and then the identification with the gaze that fully initiates diegetisation (Odin 2006: 39). Avoiding this form of identification encourages a realistic reading for the film, analogous to the voice-over, by which one can formulate ‘she is similar to me, and she is realistic.’

It is attributions coming from outside, through the voice-over, that try to explain the character of Emilie (Mamou). Emilie does not speak. She is characterised by her surroundings: empty, greyish, and rainy. The people around her do not talk, either to each other or her. She casts aimless glances around the space of the pier. The camera imitates these glances and explores the faces of the fishermen, partially detaching itself from its agenda of imitation and commenting on the character beyond observation. For example, the film mounts a shot of a full fishing bucket, in doing so figuratively declaring Emilie to be the proverbial fish out of water.

From this moment with the bucket, the film begins to slide into a diegetic reality as the son Martin takes up the word ‘disgusting’ from the voice-over into the dialogue. On the level of sound, there is a shift from the controlled voice-over to the dialogue with the ambient soundscape. The short dialogue is quickly interrupted, and another voice then takes over the spoken commentary and continues it in terms of content. The presence of ‘Varda’ as both the organising instance and a threshold figure between fiction and reality is terminated at this point. The first scene ends with the leaving of the jetty and the exposed introduction of the main characters. In the next scene, the plot begins to unfold.

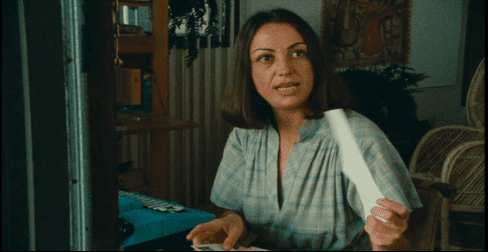

As the audience glides into the diegesis, the relationship between proximity and distance between the main character and the audience is shifted. The new closeness is constructed through various procedures: the camerawork is limited to Emilie, and her conversation with her employer Delphine dispenses with conventional techniques such as shot/reverse shot. Likewise, the conversation is followed by a point-of-view shot. The view from the window is accompanied by her thoughts (Figs. 5 & 6).

Fig. 5: TC 06:38.

Fig. 6: TC 06:53.

In this respect, the film now strives for the second level of audience identification mentioned by Odin (that of the character’s gaze) and strives not only for diegetisation but also for a perspectivisation within the diegesis, namely that it is strongly linked to the perception of the main character. It can nevertheless be described as strongly realistic. The replacement of the extra-diegetic voice-over from the opening of the film with a homodiegetic voice is both a break with the previous staging and a construction of simultaneous fiction/ non-fiction.

Mixing Elements of Documentary & Fiction

When looking out the window, Emilie becomes an observer, not a voyeur. What she observes sets off associative chains in her, which at some point also determine the images that the visual narrative instance shows. A shot of her former partner, whose composition is reminiscent of Renaissance nude paintings, follows before the image proves flexible by breaking away again and showing the protagonist looking for a flat. The view of the naked male body is not an expression of lust but of an intimacy that finds expression through the inner peace of the man’s body (Fig. 7). The timing of the voice-over is detached from the timing of the image recording, which is fed on a narrative level by the protagonist’s memories. The contrast to the first scene is significant: if the main character was still unknown and enigmatically closed off at the beginning, we now get to know her intimate secrets. Her associations jump from the body to a feeling of being at home to the house, from the house to house-hunting.

Fig. 7: TC 07:46.

Fig. 8: TC 08:50.

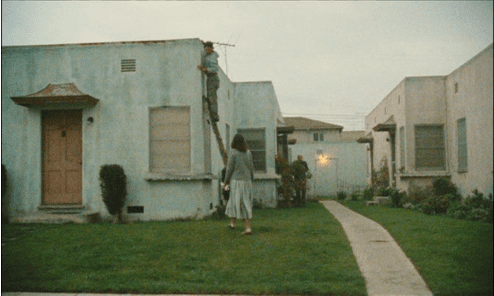

Emilie wanders through the city, aimless and determined at the same time. The first task is to find a flat, by running from door to door. The whole thing is filmed via a long shot, with the residents looking into the camera so that one can conclude that it is not an arranged shoot (Fig. 8). Sabine Mamou meets the people in her character of Emilie; the people seem to be social actors rather than performers. [3] As is so often the case, elements that are understood as reading instructions for fictionalisation collide with those that are located more in the non-fictional sphere. The confrontation of a character representation with an uninformed environment creates friction in both a realistic effect and a media-reflexive one that asks about the concrete conditions of filming. Robert Kramer’s Walk the Walk (1996) proceeds similarly by giving actors roles and letting them act out scenes with amateurs. This way, the human body becomes the interface between fiction and reality, and a special authenticity of what is filmed emerges in the here and now (Tröhler 1998: 83-84). Thus, in these moments, friction is revealed in different approaches, inviting the audience to reflect on the multi-layered processes of reception: is Documenteur a document or an as-if?

Serge Daney claims that Documenteur is more a sketch of a feature film (Daney 2000: 115). This might be attributed to a low narrativisation of the events: Emilie is a character without a distinct agenda. She is an ‘outsider that remains radically outside’ (Smith 1998: 81). It is hardly possible to sketch a model of a plot. Dramaturgically, little information about her past is laid out, and the few dialogues are hardly explicative. The film does without an exposition that would lay out the information relevant to the plot (Hartmann 2009: 46), rather, it relies on an atmospheric initiation that captures the narrative rhythm and the atmosphere of the circumstances of life in Los Angeles from whose ‘lyrical-associative forms a … connection to thematic structures’ can emerge (Hartmann 2009: 265). The thematic structures I see in this film are the search for meaning, introversion, and life in precarious circumstances in Los Angeles. The low narrativity also results from the fact that many scenes in which Emilie is physically present are subsequently intercepted by close-ups of human faces, thus interrupting the flow of the plot. Emilie and her fellow human beings are phenotypical outsiders to society, so the film depicts experiences that are individual but not exceptional.

This is particularly salient through the employment of the amateur actress Mamou, who brings no role profile due to her unfamiliarity. Since no star image overlays her performance, she offers the audience a maximum basis for identification. Tröhler understands such figures as indices for a historical situation to which these figures refer (Tröhler 1998: 87). Through the protagonist, the film shows a fascination with the residents, where the main character sometimes wonders what is going on in people’s minds but fails to gain that knowledge. About halfway through the film, the main character says that sometimes she goes to watch a certain woman when she feels lost. The woman named Millie (a phonetic anagram of Emilie), is located as another mirror figure within the diegesis. Emilie knows nothing about her but imagines how she would behave in Millie’s place. Like the Russian matryoshka doll figure, the film reveals its possible levels: that of the extra-filmic reality, the diegesis, as well as a possible metadiegesis. With each reduction of the matryoshka, there is an increasing fictionalisation, which is thematised because Emilie knows no facts about her fascination, i.e. Millie. Instead, she makes things up.

As she continues to roam the city, the protagonist observes an arguing couple, whose quarrel cannot be traced on the sound track due to the low level of the (by implication) spontaneous recording. Now, neither the ‘found’ moments (to which one rather attributes the quality of documentary) nor the scenes with Mamou as Emilie are lies, since, as Eitzen (1998) points out, one cannot accuse fiction of lying. It might be argued that the question of its potential status as ‘a lie’ determines whether a film works as documentary. As a hybrid form, Documenteur complicates this idea. The camera films the argument of the couple, the editing mounts a shot of the observer Emilie behind it. Only in the concatenation of the images do the introspection and thus the resulting fictionalisation emerge, but this does not make the two chain elements more fragile. The integration of these found moments into the narrative remains Varda’s core procedure. These moments on the streets are not only rooted in reality; they also refer to it as the basis of their claim to truth. But their connection to the fictional character of Emilie shows how this truth is understood in terms of fiction. Truth is subject to the perspective here. These moments are seen from the eyes of either the main character or the camera, as the motif of the window suggests. Just as Mur murs uses walls as a metaphor for the film itself, Documenteur uses two recurring pictorial elements as motifs: window and mirror.

Calling the screen a window has a long and sometimes controversial tradition in film studies. Put simply, the window can rather be located in a realist tradition (Elsaesser/ Hagener 2007: 26). It provides a glimpse into diegeses that are not closed but reach out and into the non-diegetic world (Elsaesser/ Hagener 2007: 28). On the side of the realist tradition, André Bazin insists with his notion of ‘Montage interdit’ (1958) that film perception is structurally related to human ocular perception, and that film should therefore aim to depict a certain social reality (Elsaesser/ Hagener 2007: 41-42). In this respect, the image of the window differs from that of the frame, which produces the reality-constructing quality of the film image. Here, the impression of realism derives from the gaze of the protagonist looking through the window. But this is undermined when the image as daydream becomes progressively more arranged and the image composition approaches the concept of the frame. It can thus be concluded that the film argues, by means of its protagonist, that the deformation of reality given perspective by the window and Emilie’s observation through it, is constructed and manifested by the frame. In these fictionalised moments, window and frame come together. Even though Emilie closes herself off from the audience with her back turned to the camera, it is clear what she is seeing, and as a result our empathy for her increases.

The frontal shot invites a psychological penetration (Brinckmann 1997: 207). In the pictorial motif of the mirror, a complex interrelation of (self-)perception and introspection emerges. Sabine Mamou’s character repeatedly looks at her reflection on a wall in her flat. The gaze in the mirror can mean many things. At this point, it is less interested in the medial qualities of film than in a narrative characterisation of Emilie’s inner life. Based on familiar and conventional forms of representation, the visual language explains Emilie as vulnerable and exposed. As can be seen in the distorted mirror image (Fig. 9), she herself does not know who exactly she is.

Fig. 9: Documenteur, TC 46:09.

Fig. 10: Documenteur, TC 15:03.

As these images suggest, these two motifs, mirror and window, occasionally coincide. The emphasis on a personal perspective is central here: instead of a ‘fly on the wall’ documentaire, we are presented with a ‘woman at the window’ documenteur (Fig 10).

The image of the mirror enables us to approach other character relationships besides that of Varda–Emilie–Millie. While searching for his mother in her new neighbourhood, son Martin observes a man sitting at the window typing on his typewriter. The man remains relatively profile-less—we learn little about him. As with Emilie at the beginning, we have to characterise him, in common with most of the people she meets, or who are observed by her or Martin, through both their environment and their fellow human beings. Individuality and collectivity clash again and again in these moments. We get to know the people in Los Angeles through their encounters with Emilie, but their individual stories are repeatedly touched upon, only to be placed as beyond Emilie’s experience. It is these experiences on which the viewer depends. Everything beyond that is speculation.

Documenteur as Trompe-l’œil

The unfolding diegesis is based on the afilmic world. This may sound banal, but in the constant comparison with reality, confusions arise that can decide the pragmatic status of the filmic world. Emilie meets a team of male filmmakers who want to make a documentary about wall paintings in Los Angeles. She is spontaneously asked to record the voice-over before the film is to be shown at the Cannes Film Festival. The character hesitantly but gladly accepts the offer and visibly enjoys this task. The protagonist speaks the exact same sentences already familiar from Mur murs. Images of the exact same murals appear, but they are filmed in a different image format than that of Mur murs so they must either have been reshot or cropped. The decisive undermining occurs when the statements are played again: the voice one recognises is not Emilie’s, but that of Agnès Varda, a fact that is waved away by the characters with the comment that they always sound different on recordings. One could attribute this to the fact that Emilie is the director’s mirror figure, but actually this constellation implies even more. The construction is not a classical mise-en-abyme, a work of art that contains itself or refers to itself. Films by Varda’s colleagues can be cited as examples of such a constellation; Truffaut’s La nuit américaine (Day for Night, 1973), for example. [4] Since it aims at the artfulness and awareness of the illusory quality of a medium, abymisation typically takes place in fictional texts (Wulff 2012). Thus, when the fictional refers to and questions the factual, it does not thematise itself to the same extent as if both films had been constructed as fictional. As a result, metalepsis appears as a means of revealing both the artifice and artfulness of the documentary. It also is a way of ennobling the open boundaries of the fictional. The narrowing of the reference levels of fact and fiction described above results here in an indissoluble knot, the threads of which are spun and woven together with relish by Varda/ ‘Varda.’ Emilie enjoys this moment of work; it gives her a task and a purpose. Otherwise, she and her son continue to drift without purpose through the coastal town characterised by silence, desolation, and disorder. The two characters hardly seem to develop at all; dramaturgically, no tension curve can be discerned. The film ends abruptly with a visit to a fair in a Hispanic district. Martin eats candy, and Emilie looks around, then kisses her son on the head. Thematically and figuratively, the film ends where it begins: with Mur murs.

The terms ‘documenteur’ and ‘mockumentary’ are used as synonyms in the German-language translation of François Niney’s Le Documentaire et ses faux-semblants (2012) as well as in the original. To what extent this is appropriate remains questionable when one compares the speech act of Documenteur with that of common mockumentaries. Etymologically, the mockumentary already suggests the act of mocking. As a rule, mockumentaries do not fictionalise their subjects: they refer specifically to a documentary aesthetic and exhibit it clearly. Documenteur’s play between clearly marked fictional moments and found moments recorded as improvised provokes an uncertainty that is much more difficult to resolve than in the case of most mockumentaries, in which one can relatively quickly set the safe attribution of the lie. The title Documenteur offers both certainty and questioning at the same time: can one speak of an intentionally false statement in fiction? If fiction cannot lie, can it speak truths?

In Niney’s typology, Documenteur could rather be classified as trompe-l’œil. The film suggests that the charms of deliberately chosen and well-understood illusion are worth more than prefabricated truths (2012: 201). At the same time, this understanding falls short since the film’s counter-image of Los Angeles is not a lie but a perspectival truth. As Bénézet (2009: 89) points out, the film oscillates between subjectivity and objectivity without committing itself to either position. In this respect, its play between closeness and distance takes place not only in its staging, which is distanced at the beginning and then moves close to Emilie’s personal experience, but also in the instructions it provides for reading the film. At the beginning, a warning is given, so to speak, against entering into the fiction contract. But this approach does not detract from the validity of the experiences offered by what follows. The concept of the ‘documenteur’ can thus be made fruitful in a new way: not as synonymous with mockumentary, but as the basis of a proposal that, while film can never adopt an objective observational perspective, its subjective gaze is always an act of fictionalisation.

The Varda Vue

At the beginning of this essay, I described Mur murs and Documenteur as two sides of the same coin. Documenteur describes seeing, Mur murs describes being seen. Mur murs gives people a face and a platform, Documenteur gives them a story. In Mur murs, street art directs the viewer’s gaze to the hardships, desires, and joie de vivre of the Chicano community; in Documenteur, found objects provide access to its protagonist’s inner life. Both films understand creative work as empowerment: Emilie finds herself in sound recording; the artists of Mur murs mark their neighbourhoods as their own. Together, Mur murs and Documenteur open a space of experience that lies at the intersection of imagination, observation, and encounter. According to Serge Daney, ‘Every film that successfully connects with our lives is a document, the rest is docucu’ (Daney 2000: 115). The techniques discussed in the essay point to a cinema that explores and exploits the distinction between fiction and documentary in order to ‘connect with our lives.’ It is this way of seeing that I call the Varda vue.

Notes:

[1] I will differentiate between Varda, the real person grounded in reality, and the persona ‘Varda,’ the director present in the film.

[2] For both Mur murs and Documenteur, there is an alternative English language version, which Varda has dubbed herself. I have used these versions while writing this paper.

[3] I use Bill Nichols’ phrase ‘social actors’ (2001) as the term for participants in documentary film.

[4] In this film, François Truffaut plays the director of the melodrama Je vous présente Paméla. We follow both the plot of the film and its staging.

REFERENCES

Beyerle, Mo & Christine N. Brinckmann, (eds) (1991), Der amerikanische Dokumentarfilm der 60er Jahre: Direct Cinema und Radical Cinema, Frankfurt am Main/ New York: Campus, pp. 29-53.

Branigan, Edward (1984), Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film, Berlin/ Boston: De Gruyter.

Brinckmann, Christine N. (1997 [1996]), ‘Das Gesicht hinter der Scheibe’ in Christine N. Brinckmann (ed.), Die anthropomorphe Kamera: Aufsätze zur filmischen Narration. Zürich:Chronos, pp. 200-214.

Brunner, Philipp & James Hüningen (2011), ‘Magischer Realismus’, Lexikon der Filmbegriffe, https://filmlexikon.uni-kiel.de/index.php?action=lexikon&tag=det&id=2981 (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Bénézet, Delphine (2009), ‘Spatial Dialectic and Political Poetics in Agnès Varda’s Expatriate Cinema’, Journal of Romance Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 85-100.

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), The Cinema of Agnès Varda. Resistance and Eclecticism, London: Wallflower Press.

Daney, Serge (2000), ‘MUR MURS und DOCUMENTEUR von Agnès Varda’ in Christa Blüminger and Serge Daney (eds), Von der Welt ins Bild: Augenzeugenberichte eines Cinephilen, Berlin: Vorwerk 8, pp. 114-117.

Eitzen, Dirk (1998), Wann ist Dokumentarfilm? Der Dokumentarfilm als Rezeptionsmodus, Montage AV, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp.13-44.

Elsaesser, Thomas and Malte Hagener (2007), Filmtheorie zur Einführung, Hamburg: Junius.

Fludeirnik Monika, Nicole Falkenhayner & Julia Steiner (2015), ‘Einleitung’, in Monika Fludeirnik, Nicole Falkenhayner & Julia Steiner (eds), Faktuales und Fiktionales Erzählen. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven, Würzburg: Ergon, pp. 7-22.

Grierson, John (1933), The Documentary Producer, Cinema Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.7-9.

Hartmann, Britta (2009), Aller Anfang: Zur Initialphase des Spielfilms, Marburg: Schüren.

Hartmann, Britta (2012), ‘Anwesende Abwesenheit: Zur kommunikativen Konstellation des Dokumentarfilms’, in Julian Hanich & Hans J Wulff (eds): Auslassen, Andeuten, Ausfüllen: Der Film und die Imagination des Zuschauers, München: Fink, pp.145-159.

Metz, Christian (1997), Die unpersönliche Enunziation oder der Ort des Films, Münster: Nodus.

Nichols, Bill (2001), Introduction to Documentary, Bloomington/ Indianapolis: Bloomington University Press.

Niney, François (2012), Die Wirklichkeit des Dokumentarfilms. 50 Fragen zur Theorie und Praxis des Dokumentarischen, Marburg: Schüren.

Odin, Roger (2006), ‘Der Eintritt des Zuschauers in die Fiktion’, in Alexander Böhnke, Rembert Hüser & Georg Stanitzek (eds), The Title is a Shot. Das Buch zum Vorspann, Berlin: Vorwerk 8, pp. 34-41.

Smith, Alison (1998), Agnès Varda, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Tröhler, Margrit (1998), ‘WALK THE WALK oder: Mit beiden Füßen auf dem Boden der unsicheren Realität. Eine Filmerfahrung im Grenzbereich zwischen Fiktion und Authentizität’, Montage AV, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 79-90.

Westley, Hannah (2006), ‘Second reel’, The Guardian, 28 August 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2006/aug/28/art.france (last accessed 9 August 2023).

Witte, Karsten (1993), ‘Was haben Kinder, Amateure, Sterbende gemeinsam? Sie blicken zurück’, in Ernst Karpf, Doron Kiesel & Karsten Visarius (eds), Kino und Tod. Zur filmischen Inszenierung von Vergänglichkeit, Marburg: Schüren, pp. 25-51.

Wulff, Hans J. (2012), ‘Mise-en-abyme’, Lexikon der Filmbegriffe, https://filmlexikon.uni-kiel.de/index.php?action=lexikon&tag=det&id=7500 (last accessed 22 April 2023).

Films

Black Panthers (1968), dir. Agnès Varda.

Daguerréotypes (1975), dir. Agnès Varda.

Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her) (1967), dir. Jean-Luc Godard.

Dialogues with Madwomen (1994), dir. Allie Light.

Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda.

La nuit américaine (Day for Night) (1973), dir. François Truffaut.

Le lion volatil (2003), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les 3 boutons (2015), dir. Agnès Varda .

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnes) (2008), dir. Agnès Varda.

Mur murs (1981), dir. Agnès Varda.

Tongues Untied (1989), dir. Marlon Riggs.

Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017), dir. Agnès Varda and JR.

Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), dir. Agnès Varda.

Walk the Walk (1996), dir. Robert Kramer.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey