The Sarah Everard Clapham Common Vigil: London, 13/03/2021

by: Margherita Sprio , March 28, 2021

by: Margherita Sprio , March 28, 2021

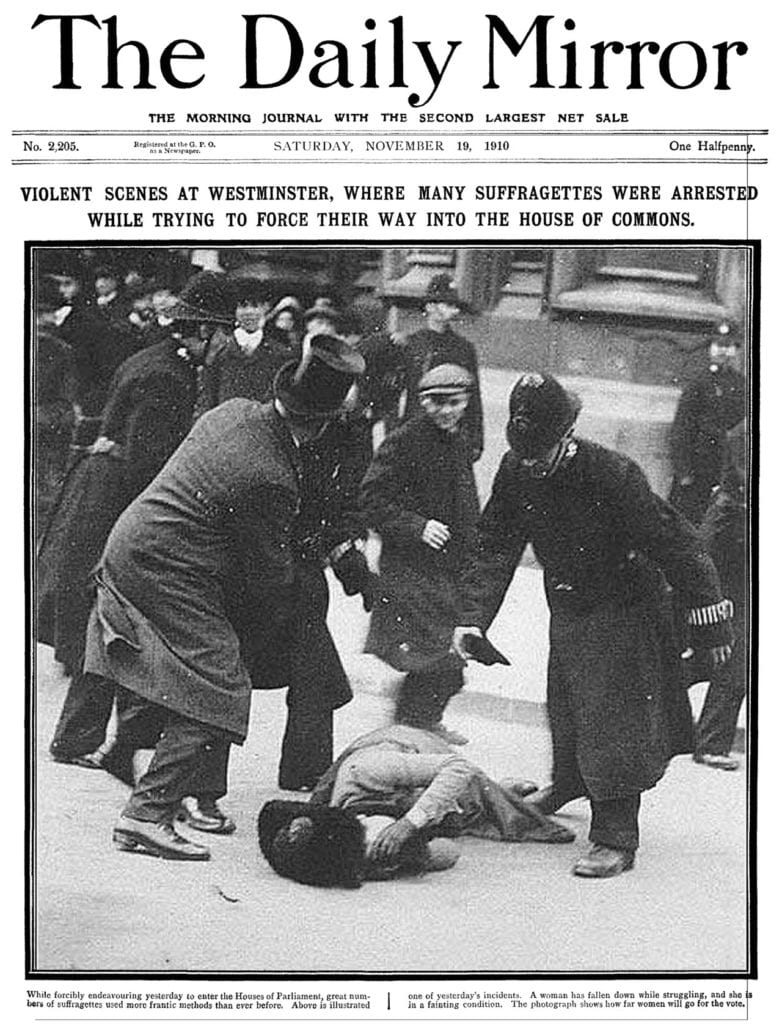

One of Sarah Everard’s friends has asked for her tragic murder not to be politicised, but of course this death is as political as all other deaths of women at the hands of men. [1] As we can see from the image of the front page of The Daily Mirror in 1910, the ‘manhandling’ of women, in this instance the suffragettes, by the police is not new or recent. To conflate these occurrences is to point to the immediate truth that the alleged kidnapping and murder of Everard was at the hands of a serving Metropolitan police officer. Without wanting to prejudice the court case in any way, but also because of the feelings of nausea that accompany any mention of his name, here he will be referred to as Mr Policeman.

It is now known that Mr Policeman had ‘indecently exposed’ himself to a different woman in a South London fast-food restaurant on 28 February 2021, only four days before he allegedly committed this murder. Had he been suspended for this action, Everard could still be alive today—we shall never know. What we do know is that such an offence was not deemed disturbing enough to stop this officer from continuing to serve his country via his usual day job as a Parliamentary and Diplomatic Protection Officer for government buildings. It was after this work shift guarding the American Embassy in Battersea in London that he allegedly kidnapped and murdered Everard. Evidence-based medical research, as well as audiences that form part of the global obsession (Turnbull 2015) with television crime dramas that feature violence against women as the central core of their narratives, already know that it is very unlikely that men commit such crimes against women only once. (Magestro 2015) It is highly probable that men who expose their genitals to women in a public space are very likely to repeat such offences, as well as commit others that are worse. (Jung 2018: 576-592) Mr Policeman had been a serving police officer since 2018, after having previously worked as a car mechanic.

It would seem that there are questions to be asked about the filtering process for training new recruits that might miss the rampant misogyny that exists in its ranks. Serving police officers are a mirror into existing views of women that society holds, and so it is not a surprise that some hate women as much as other men do. The experience of the behaviour patterns of some men when in groups with other men is something that most women could offer a negative perspective on. If this is considered in the light of those who are paid to serve and protect us when we already know that ‘bad apples’ [2] exist in all aspects of society, it might offer a clue as to why women never feel entirely safe to walk alone in public spaces. The recent widespread media coverage in Britain of the lengths that women go to in order to feel comfortable when walking in their already demarcated public spaces, is something that also gives a good indication of the amount of energy women have to exert in order to partake in a basic human right.

The double bind that has seen restrictions placed on all bodies during the pandemic—trying not to get ill with Covid whilst also needing fresh air and exercise—has also highlighted the different ways that men and women are forced to behave in order to stay safe. The restrictions placed on us by our governments are countered by those we place on ourselves. There is an inner voice that tells us it is safer not to go out for a walk at night after our working day under the current lockdown rules, as there are so few people out, and this makes a woman more vulnerable than at other times. Were there to be any visible police presence we might feel safer—or not. During lockdown, it has been common to see the occasional slow-moving police van in London’s popular large parks. However, this is so that social distancing rules could be enforced, rather than for other forms of public safety, since the scale of such spaces would suggest the need for larger numbers of officers.

There was a sudden influx of numerous officers on the night of the Vigil for Everard at Clapham Common in South London on 13 March 2021. This was an unexpected presence, because the Reclaim These Streets Vigil had been cancelled due to police pressure and bullying, and yet women had independently wanted to go to the site where Everard had last been seen alive. Reported numbers of participants have varied from between five hundred to a thousand throughout the day, and similar events had been planned throughout other parts of Britain. Women wanted to pay their respects, to mourn, to grieve and to be with other women—there were some men there too, but in much smaller numbers. Women held candles, laid flowers, shone torches from their mobile phones. This is the very symbol of what women search for when out alone at night—a light source that offers them comfort and a clearer path to safety.

We all willed Everard to be found alive and well in the days between her reported disappearance and her discovery in woodlands, but we all had our doubts too. Women do not simply disappear, and her last sightings on street cameras showed us the ordinariness of walking home alone through the city at night. The circumstances of what exactly happened next are yet to be determined, but we do know that subsequent to Everard’s body being found in Ashford, Kent, another serving Metropolitan Police Officer who was guarding the cordoned area of the crime scene, decided to send out a sick meme to colleagues on WhatsApp that joked about her kidnap and murder. He is said to have shared the meme which showed six different images the day after Everard’s body was found. Some of his colleagues reported the incident to their superiors, which then resulted in the officer being removed from the murder investigation and placed on restricted duties with no direct involvement with the public. As well as revealing the existing culture of the Metropolitan Police, this action echoed another similar incident last year, and this shows that in spite of the phrase that is so often repeated—that ‘lessons have been learned’–it would seem that nothing at all has changed.

On 7 June 2020, the bodies of sisters Nicole Smallman, 27, and Bibaa Henry, 46, were found at Fryent Gardens in Wembley, London, two days after a birthday party in the local park. They had been stabbed multiple times by a male teenager not known to them, and it was reported that the murder was an ‘unprovoked and random attack’. Aside from the issue of the very slow response from the police when their disappearance was reported, which led to the family taking it upon themselves to return to where the women were last seen in the park, and for their bodies and the murder weapon to be discovered by Smallman’s partner, there is a chilling similarity between the type of culture of policing exhibited both here and in the case of Everard. Subsequent to the cordoning off of the crime scene where the sisters were found, two Metropolitan Police Officers were suspended after ‘inappropriate photos’ were taken by them and shared on WhatsApp. It was claimed that both officers took selfies next to the sisters’ bodies, and their mother rightly claimed that such pictures ‘dehumanised’ her children, ‘They were nothing to them and what’s worse, they sent the pictures on to members of the public.’ Wilhelmina Smallman, the Church of England’s first female archdeacon of colour said, ‘If ever we needed an example of how toxic it has become, those police officers felt so safe, so untouchable, that they felt they could take photographs of dead black girls and send them on. It speaks volumes of the ethos that runs through the Metropolitan Police.’ [3]

A further investigation was launched to examine the conduct of an additional six officers who allegedly were either aware of, received, or viewed the inappropriate photographs and failed to challenge or report them. As a result of this, thirteen officers in total were informed that their conduct was under investigation for potential breaches of standards of professional behaviour. Of these thirteen, two were suspended and five were put on restricted duties. Not wanting to belabour the issue of the training that is offered to police recruits, it is worth noting that the encrypted modality that governs the functionality of WhatsApp, means that officers are free to choose what they photograph and send to each other. However, might it also be true that officers in Everard’s case knew that their behaviour towards the sick meme they were sent could land them in trouble, so it was easier to report their colleague and hence avoid what had happened to others in the case of Smallman and Henry. What we never get to hear about is what exactly is done to change the culture from the inside once these appalling acts are discovered. The performative nature of vilifying a few ‘bad apples’, suspending or even sacking them, does not deal with the misogyny within the police force and the wider society at large. (Chan 1996: 109-134)

A Facebook group had been set up in preparation for the planned event for Sarah Everard before the vigil was forced to be cancelled. On Clapham Vigil stated: ‘We have come no further. Our only freedom right now is to walk, and we can’t do it alone at night without fear of harm. So let’s walk together.’ One woman who attended the vigil, and will remain nameless, reported that she witnessed a man expose himself there. The Metropolitan Police have launched an appeal describing him as ‘white, aged approximately 50 years old, around 5ft 6ins tall with grey hair’ and that he was wearing ‘a red waistcoat or vest over a shirt and light-coloured trousers.’ Curiously, they go on to say that ‘We also cannot discount that there may have been other instances of this nature in and around the Clapham Common area, so I would urge anyone who has witnessed this to get in contact.’ There had been much whispering between women about creepy men cruising the Common at night—women are on constant alert for such discomforts. An event that was in honour of a murdered woman would not have stopped these types of men coming out to play. The now-iconic image of Patsy Stevenson’s arrest at the Everard vigil, taken by The Times photographer Jack Hill, returns us to the start of this essay and the main image that accompanies it.

Like every circular narrative, we end at the point from which we started. As the suffragettes protested for our right to power, the four women who were arrested at the Vigil were all confined to the darkness of the hour. Why did the Metropolitan Police decide to come out in large numbers and with full force as soon as daylight was fading? Is darkness the time when some men feel they can behave as they like, and use as much disproportionate physical aggression as they see fit? The stillness of the women being arrested, their inability to fight back against such brute force, and the sheer number of officers holding them against their will, echoed the experience of women globally. As the world watched in horror and rage at the mistreatment of women who were masked against COVID and holding flowers and candles, the Metropolitan Police singlehandedly tarnished the last piece of trust women across London (and beyond) had in them.

One final addition to this piece that haunts the spaces occupied so far, is the death by drowning of Blessing Olusegun who was a 21-year-old student from South London who had been undertaking a work placement as a carer for elderly patients with dementia in Bexhill in East Sussex. On 18 September 2020, a week into her placement, Blessing was reported missing, and was later found dead on Glyne Gap Beach in Bexhill-On-Sea. At the time, the police said that here was no evidence of external or internal injury, so her death was deemed ‘inconclusive’ and was not treated as suspiciousTop of Form. An online Bottom of Form petition started by her friends is calling for Sussex Police to continue actively investigating her death, describing Blessing as, ‘Our beautiful gorgeous talented independent Queen.’ The petition, which currently has more than 35,000 signatories, also states that Blessing’s last conversation was with her mother, at around 00.30 am. Like Everard, who spoke to her partner on her walk home on the night she is believed to have died, Blessing also contacted her partner via text messages, as well as speaking to a close family friend asking them to ‘stay on the phone to her as she goes for a walk in the night’. It is to be welcomed that the tragedy of Everard is shining a new spotlight on this case, but why is it that all deaths of women are not given the same amount of attention and police investigative resources?

Cressida Dick, the first ever woman Metropolitan Police Commissioner, sought to reassure women in the wake of Everard’s death by saying ‘it is thankfully incredibly rare for a woman to be abducted from our streets.’ She neglected to mention the significance of the behaviour patterns of some of her serving officers, or to offer any reassurance about how both current and future police training might be addressed by recent events. It was not lost on any of her listeners that in this instance, it had been one of her serving officers who had abducted and murdered a woman. It is the conduct of her officers and their use of social media to further denigrate women that needs to be urgently addressed. (Bullock 2018: 245) She went on to fully support the officers who aggressively ‘manhandled’ the attendees of the Vigil using the pandemic as the cover for such violence. In another constabulary, the recent release of a vivid CCTV street recording [4] shows a probationary police officer with West Midlands Police, grabbing Emma Homer on a dark street last July 2020. In his defence, his lawyer argued he should not have to do community service because it would be ‘difficult’ for him to work with criminals. Instead the officer was sentenced to a 14-week curfew, banning him from leaving his house between 7 pm and 7 am and ordered to pay Homer £500 compensation and £180 court costs.

RIP:

Sarah Everard (1987-2021)

Nicole Smallman (1993-2020)

Bibaa Henry (1974-2020)

Blessing Olusegun (1999-2020)

Notes:

[1] See Helena Edwards’ article here: https://www.spiked-online.com/2021/03/13/this-is-not-what-sarah-would-have-wanted/ (last accessed 28 March 2021).

[2] The bad apples metaphor originates from the proverb, ‘A rotten apple quickly infects its neighbour’ (English use 1340). The term was first used in the media by the American police in relation to the beating of Rodney King when the filmed police brutality he received by four police officers caused global outrage in 1991. The officers responsible were subsequently acquitted of any wrong doing which sparked the Los Angeles riots in 1992. More recently, the term was again used in defence of the use of excessive police brutality in the deaths of Breonna Taylor (2020) and George Floyd (2020). In Britain it is a term that became synonymous with the murder of the teenager Stephen Lawrence and the subsequent Inquiry (written by William Macpherson, 1999) into the way that his death was mismanaged by the London Metropolitan Police.

[3] For the full interview, see – https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-53198702 (last accessed 28 March 2021).

[4] The film is available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/mar/19/west-midlands-police-officer-attacked-woman-pc-oliver-banfield (last accessed 28 March 2021).

REFERENCES

Books:

Magestro, Molly Ann (2015) Assault on the Small Screen: Representations of Sexual Violence on Prime Time Television, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Turnbull, Sue (2014) The TV Crime Drama, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Journal Articles:

Bullock, Karen (2018), ‘The Police Use of Social Media: Transformation or Normalisation?,’ Social Policy and Society, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 245-258.

Chan, Janet (1996), ‘Changing Police Culture’, The British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 109-134.

Jung, Sandy (2018), ‘Sexual Violence Risk Prediction in Police Context’, in Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, Vol. 30, No.5, pp. 576-592.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey