The Texture of Time: Varda & the Possibility of a Feminist Essay Film

by: Lydia Tuan , November 7, 2023

by: Lydia Tuan , November 7, 2023

The term ‘essay film,’ used to define the aesthetic of a cinematic category that blurs the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction and alternates between the documentary and the experimental, has been prominent in recent scholarship, notably within the Anglophone context. However, other than occasionally using the term ‘film-essai,’ French scholars prefer to emphasise the essayistic aspect of the category, with expressions such as ‘essai cinématographique,’ the ‘essai filmique,’ or even the ‘essai au cinéma.’ According to Timothy Corrigan, film’s essayistic form emerged from the photographic essay and, as such, began with the work of Left Bank directors in Paris, especially Chris Marker, who inaugurated a new aesthetic characterised by the political use of voice-over. [1] Their films (especially those of Marker, Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda) stand out from the work of other directors less contentiously associated with the French New Wave by highlighting socio-political issues and drawing on documentary as the most suitable film genre for producing politically-committed cinema.

Whilst numerous women’s essay films can be found in the European Francophone context, Agnès Varda’s use of the essayistic form is particularly remarkable in that her aesthetic has been formative in defining her own status as an auteur. [2] While she made documentaries throughout her career, the beginnings of her autobiographical essayistic turn can be traced to the 1990s (a decade marked by the passing of her husband, Jacques Demy, in 1990) until her own death in 2019. Jacquot de Nantes (1991), the first of these films, focuses on Demy’s life as a filmmaker and as Varda’s husband, paying homage to his life with re-enactments of moments from his childhood. The film includes a scene from Demy’s death and heralds Varda’s more confident essayistic aesthetic in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000), followed by its sequel two years later, Les glaneurs et la glaneuse… deux ans après (The Gleaners and I… Two Years Later) (2002).

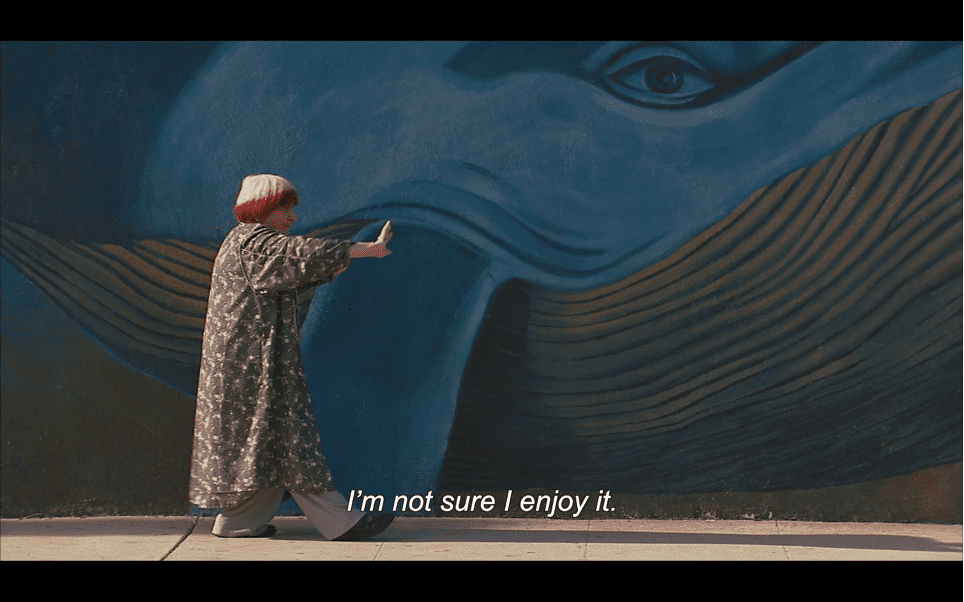

In 2008, with Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès), Varda began to transform herself more explicitly and consciously into a work of art, placing herself in the centre of the frame with mirrors framing and reflecting her in the first scene of the film. In Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017) enlarged images of various body parts are attached to buildings and trains. Varda’s last film, Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), features a more explicit self-exploration of Varda as an established auteur, in which she explains how her work evolved over the years and influenced the cinematic medium as a whole. [3] In this final film, Varda continues to put her contribution to the history of French cinema on display by framing her own body as the very subject of her filmmaking.

This article therefore considers Varda’s essay films as primarily a form of self-portraiture through detailed analyses of Les glaneurs et la glaneuse and Visages Villages by exploring Varda’s use of the essayistic form to make connections between biological time (acknowledging Varda’s on-screen presence in her films as both a director and an aging woman) and cinematic time. These films, categorised as documentaries that feature the essayistic aesthetic, are characterised by an abundance of close-ups of Varda’s body. This device both underlines the intimate relationship between the filmmaker and the cinematic image and shows how Varda frames and treats her body as a cinematic, haptic image. It is in this very exploration of her identity as a director and an aging woman that Varda’s approach to the essayistic can be defined as feminist. My discussion of Varda’s framing of her body as an art object invites further reflection on how Varda’s use of the essayistic might have influenced the work of other contemporary female directors who have also emphasised the corporeal dimension of filmmaking, treating cinema as a temporal medium of self-portraiture and self-preservation.

The Essay Film

The essay film as an aesthetic form dates back to the early 1940s. The term was used by the mid-1950s and understood as an aesthetic liberation from the narrative structure of fiction films. [4] This understanding coincided with the popularisation of ciné-clubs in France between the early 1940s and the late 1970s, which introduced French audiences to the idea of watching films for intellectual debate as well as entertainment (Corrigan 2011: 66). [5] By the 1970s, the essay film had gone global, and was adopted by filmmakers such as Wim Wenders, Harun Farocki, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Trinh T. Minh-ha.

Despite the consensus that the essay film is, by definition, undefinable (Moure 2004: 36), Timothy Corrigan emphasises the generic and aesthetic connection between the essayistic and the experiential confrontation of a subjectivity with the public domain: ‘the essayistic acts out a performative presentation of the self as a kind of self-negation in which narrative or experimental structures are subsumed within the process of thinking through a public experience’ (2011: 6). Like the paradoxical meaning set by Moure in his definition of the essay film, Corrigan underscores that the essay film can both be a presentation of the self or its disruption: ‘Essayistic expression (as writing, as film, or as any other representational mode) thus demands both loss of self and the rethinking and remaking of the self’ (2011: 17). Thus, the essay film puts forward a voice and implies a performance of the self that is central to the definition of the essayistic. As such, Laura Rascaroli recognises the essay film’s traditional link to political cinema as a fundamental component of the essayistic aesthetic: ‘to speak “I” is, after all, firstly a political act of self-awareness and self-affirmation’ (2009: 2).

The connection between the essay film and the self has led to the scholarly claim that voice-over narration is a common, though not defining, characteristic (Lopate 1992: 19; Rascaroli 2008: 37-38; Rascaroli 2020: 75-76; Önen 2019: 93). By contrast, David Oscar Harvey’s theory of the ‘non-vococentric’ essayistic argues that the prioritisation of a vococentric essay film departs from Alexandre Astruc’s 1948 definition of the caméra-stylo focusing attention on the non-vococentric image (Harvey 2012: 7). Harvey contends that the subject of the filmic self-portrait has the capacity to express itself beyond the presence of a human voice narrating its thoughts. Harvey states: ‘rather than taking the form of a voice-over remarking upon images, the voice emerges from the play and arrangement of the images’ (2012: 19).

The primary interrogation of the self that is core to the essay film is likely to explain its fascination for Varda. Her cinema is driven by the attempt to simultaneously construct and deconstruct the individual through the framing of parts of her own body in close-up as the primary expression of self. Varda portrays her body as both complete and incomplete, stuck in a process of constant integration and disintegration, in which the fragmentation of the body functions as an essential aspect of her essay films and the very basis of her feminist filmmaking. [6]

From Astruc’s ‘Caméra-Stylo’ to Varda’s ‘Corps-Stylo’

Varda’s major feature-length films since 2000 have focused on a separate body part, with the very texture of her body, skin, or eyes becoming the cinematic fabric of her essay films. On the one hand, Varda’s presentation of her body as a work of art and subsequent fragmentation of it into images to be analysed cast light on her own creative process and motivations for making her films. Varda’s cinema is self-conscious: her films are saturated with references both to cinema as a medium of representation and to the language of filmmaking. [7] The films work as cinematic reconstructions of her own physical being, aesthetic duplications of the self that interpret, very literally, the definition of the essay film as a subjective or personal camera.

On the other hand, Varda’s camera works as a microscope zooming in and temporally tracking the aging process of her own body and its metamorphosis, in addition to highlighting her life as a woman. Through this process, Varda splits into multiple personas, becoming at once the filmmaker, an aging woman, a spectator of her own aging, and the protagonist in her own film. Thus, Varda produces a uniquely corporeal cinema in which cinematic time becomes explicitly biological and is visualised on screen as texture. This combination of body image and time image may therefore be read quite literally as a corporeally organised filmography. In this respect, it seems fitting to redefine her well-known theory of cinécriture—‘writing with cinema,’ Varda’s attempt to capture the specificity of cinema and its autonomy from other arts such as literature or painting—as corps-stylo (‘body-pen’): writing the self with and through the body.

Varda’s prioritising of the presence of the corporeal as the primary material of the temporal, cinematic image in her use of the essayistic is consistent with Harvey’s characterisation of the filmic self-portrait as privileging non-vococentrism (Harvey 2012: 7). In Les glaneurs et la glaneuse…deux ans après, Les plages d’Agnès and Visages Villages, Varda’s subjectivity is expressed through the surface of the image rather than sound and narrative voice. Delphine Bénézet reframes Varda’s approach as carnal cinematography whereby shots of the body intrigue the spectators, creating what Bénézet calls ‘Varda’s cinema of interpellation’ (2014: 123). Bénézet’s reference to ‘carnal cinécriture’ (cinécriture charnelle) cites Kate Ince, who—combining haptic theory with Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception as typically done by other haptic film scholars writing on phenomenological film theories—argues that the carnality of Varda’s cinécriture results from the erotic gaze she casts on the framed subject (2013: 604).

Building on the term ‘carnal cinécriture,’ this article considers the framed subject—that is, the framed flesh—by moving away from Ince’s idea that it results in an erotic gaze presupposed by the presence of an external, male gaze. I argue that images of framed flesh in Varda’s essay films represent markers of time in relation to Varda’s physical centrality in her own cinema, in which her various temporalities as a framed subject, a woman, and a director are all inscribed and narrated spatially through close-ups of her fragmented body parts. I apply Ince and Bénézet’s concept of ‘carnal cinematography’ more specifically to the relationship between Varda and her understanding of cinema as an art form as suggested above and propose that Varda considers her own body as a cinematic object, at times as a cinematic image or surface, and at others as a camera.

It is, therefore, essential to stress the significance of the temporality of the cinematic image in Varda’s essay films. In Les glaneurs, the exaggerated close-up of her skin fills the profilmic space, becoming at that moment a tactile surface of the cinematic image. When Agnès walks backwards in a scene in Les plages d’Agnès, her body mimics that of a rewinding camera as she attempts to access the memories of her youth and represents cinema as a corporeal medium (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Agnès walking backwards in Les plages d’Agnès (2008).

Fig. 1: Agnès walking backwards in Les plages d’Agnès (2008).

Time is also haptic for the filmmaker, and every frame of her body serves as an image of the texture of time, both biological and cinematic. As a result, the spectatorial gaze in Varda’s feminist essay films is internal, looking out from within. This mode of understanding Varda’s multiple corporeal close-ups suggests that viewers assume the gaze of Varda’s gaze on herself as a subject. This is a fundamental feminist mode of filmmaking. For art historian Jennifer Stob, ‘Varda always located the origins of her feminism in her personal search for identity as a woman, and in her own body’s negotiation of the roles of artist, lover, and mother’ (2022: 16). In Les glaneurs, Deux ans après, and Visages Villages, Varda puts her own body on display not as an object of desire, but rather as the primary mode through which to centralise cinema as a main subject in her essay films, explore her relationship with the medium, and, to a greater extent, self-consciously establish herself as an auteur in the history of French post-war cinema. The viewer also adopts the perspective of an aging woman as the primary gaze through which to see the world that Varda offers on camera. In the remainder of this article, I will consider Varda’s feminist, corporeal filmography through a temporal framework focusing on the parallels between cinematic time and biological time in all three films.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse: The Hand of Agnès

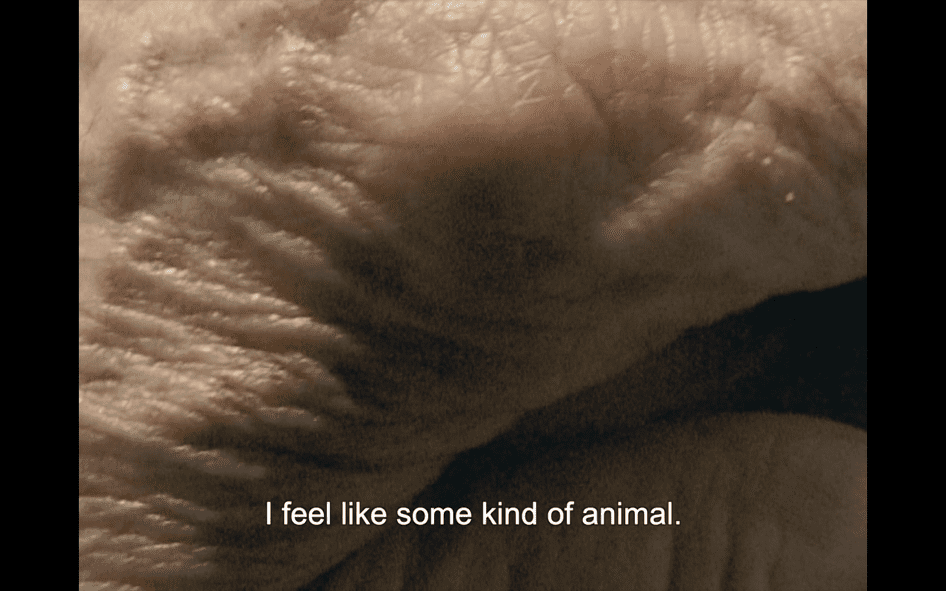

In Les glaneurs, Varda very often frames her hands in close-ups that reveal the texture of the skin. The emphasis on the hand in this film is important for its relationship to cinema, in which the framing of the hand emphasises the manual, tactile act of filming and editing. At the beginning of the film, Varda tells us through voiceover that this film is both autobiographical and socio-cultural. She is as interested in the construction (or ‘gleaning’) of a self-portrait as she is in meeting and speaking to people who glean by necessity or choice. The gesture of gleaning in this film structures the content and theme of the film as well as its technique: Varda’s cinematic essay is the result of ‘gleaning’ from archival images and footage. Within the film, she explains the parallel between this approach and the socioeconomic importance of gleaning in French history, whereby laws have protected the right of French citizens to glean at certain times of the day and in certain areas.

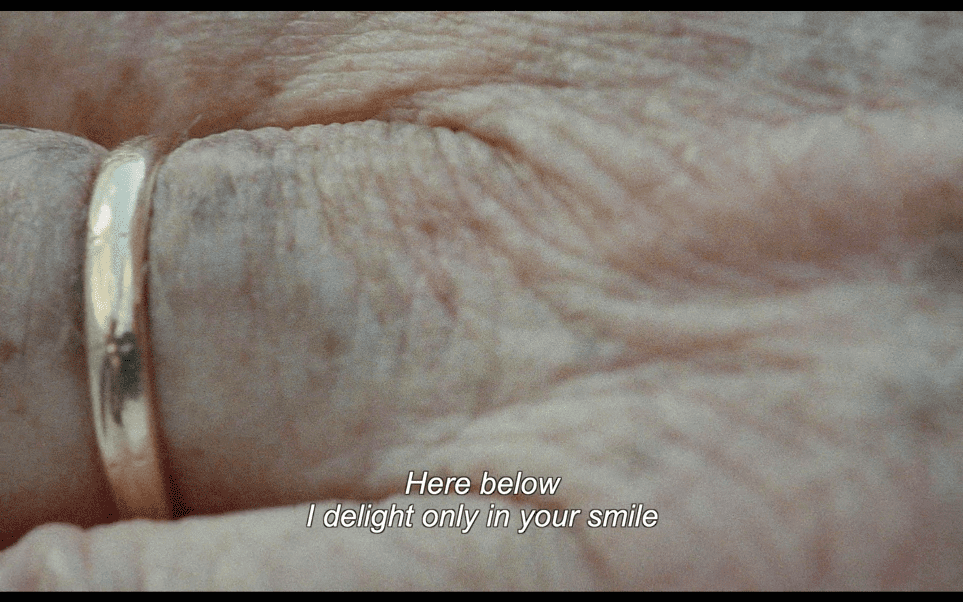

Varda’s intention with Les glaneurs is to create a manual self-portrait. She describes it as a self-portrait constructed by one hand filming the other. As she frames Rembrandt postcards purchased on a trip to Japan, Varda exclaims that filming one hand with the other produces the effect of ‘rentrer dans l’horreur’ (entering into the horror) of her body, making her feel like a strange and savage animal. Filming the self thus produces a brief out-of-body experience, in which the hand being filmed momentarily becomes a separate entity from that of the filmmaker. It becomes a foreign entity through the very process of self-representation, entering, she explains, into the horror of the unknown. At the end of Deux ans après, Agnès reflects on the making of her first film and refers to journalist Philippe Piazzo’s view that the close-ups of Agnès’ hands and hair evoked her framing of Demy’s arms and hands in Jacquot de Nantes. Her portrait of Demy framed his skin in close-up, tracking the camera down his arm to his ring finger. The scene represents his life history and passing of time from childhood to the present, or more precisely the ‘present’ that Varda shares with him as at the time of shooting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Extreme close-up of Jacques Demy’s hand in Jacquot de Nantes (1991).

Fig. 2: Extreme close-up of Jacques Demy’s hand in Jacquot de Nantes (1991).

The shot focuses on the temporality of its subject and is a haptic engagement with temporality, whereby the camera’s touching of the skin via the close-up is tantamount to touching the past, touching history, and touching the passage of time itself. It is undoubtedly an intimate image, in which the extreme close-up reflects the desire to maintain and capture the intimacy between the character and the viewer (as well as Varda herself), to understand and feel through touch.

Varda’s attempt at self-portraiture in Les glaneurs was not universally well-received. When Agnès reunites with Alain Fonteneau in the sequel to Deux ans après, Alain admits to not liking her self-portrait, especially the close-up shots of her wrinkles and age spots on her hands. These are precisely the scenes that feature a cinematic ‘gleaning’ of her body and reveal her engagement with the essayistic as feminist mode of filmmaking. The act of framing in close-up, both literally and figuratively, highlights the introspection and self-reflection that allows for the director’s essayistic engagement with the self, one that is predicated on assuming the perspective of Agnès reflecting on her own aging and corporeal transformation through time. Read through the perspective of a feminist essay film, the role of the digital camera in Les glaneurs highlights the proximity and instantaneity of the new technology offered by the digital. As a device, it also functions as a mirror and a microscope in relation to her own identity as an aging woman, which goes beyond her use of the camera as a filmmaker. The irrelevance that Alain finds in Varda’s own self-portrait is predicated on the idea that Varda holds one identity as the film’s director, overlooking the multiple presences and roles that Varda takes on in her film.

Varda is very much aware of her own multiple presences in Les glaneurs. As the film’s French title suggests, she presents herself as a female gleaner amongst other gleaners, as she compares filmmaking to a creative form of gleaning. The physical, tactile, and manual gesture of bending down to pick up something from the ground is used to evoke the manual side of filmmaking. Through the importance of the hand in the film, the texture of time is also evoked through the parallel between touch and sight. In other words, Varda’s filmmaking is one that invites the viewer to ‘touch’ her body through sight. The resulting image in close-up embodies the intimacy produced by her cinema, shot from her point of view, as well as the ability of digital filming techniques to create an instantaneous cinema.

The image of the heart-shaped potato, which has become a well-known symbol of the film, also plays an important role in the construction of her self-portrait. At times, it replaces Agnès’ body and acts as a metaphor for the self. Varda frames the potato in close-up, emphasising the dusty and spotted surface of the potato as an extension of the sunspots and wrinkles on her own aging hands (Figs. 3-4).

Figs. 3-4: Close-up of Agnès’ hand and close-up of a heart-shaped potato in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (2000).

Figs. 3-4: Close-up of Agnès’ hand and close-up of a heart-shaped potato in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (2000).

She finds pleasure in watching the potato grow, sprout, shrivel, rot, as much as she enjoys watching herself age. Varda links her film to the maturation of her own biological body, and she compares the surface of her skin to that of a potato, studying herself as she physically changes over the course of filming. It is no coincidence that the final images of the film, as well as the closing credits of Deux ans après, show heart-shaped potatoes, wrinkled, sprouting, and decaying but as proudly curated as works of art (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Close-up of a wrinkled and sprouting potato in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse…deux ans après (2002).

Fig. 5: Close-up of a wrinkled and sprouting potato in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse…deux ans après (2002).

As Mireille Rossello writes on the topic of the director’s self-portrait as an old woman, allusions to death in Varda’s cinema are often ‘framed in such a way as to question our assumptions about coherence, and Varda’s seemingly parenthetical close-ups on her ageing hands, on her white hair, are also the equivalent of gleanable filmic material: what we cannot make sense of during a first viewing is like what was not harvested by a grubbing machine’ (2001: 33).

Varda’s film is not limited to images of death, as these ‘parenthetical close-ups’ are not merely parenthetical. I argue that the scenes focusing on her aging present us with an image of temporality as a cinematic concept. Cinema, like the human body, captures temporality and records it on its surface: it is an audiovisual medium, like a wrinkled and germinated potato, which bears on its surface the inscriptions of a temporal passage. I therefore propose that the corporeal close-ups of her hands should not be regarded as a feminist response to accepted beauty standards, but as reflections of her fascination with cinema as an audiovisual and spatial-temporal art form. Varda’s attempts to grab at trucks passing by on the motorway highway (Fig. 6) likewise evoke the desire to capture and hold on to time. As a temporal medium, cinema fulfils the same role. Varda makes this connection by framing both herself and the heart-shaped potato in close-up as an extension of herself in place of the cinematic medium.

Fig. 6: Agnès ‘capturing’ a truck with her hand in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (2000).

Fig. 6: Agnès ‘capturing’ a truck with her hand in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (2000).

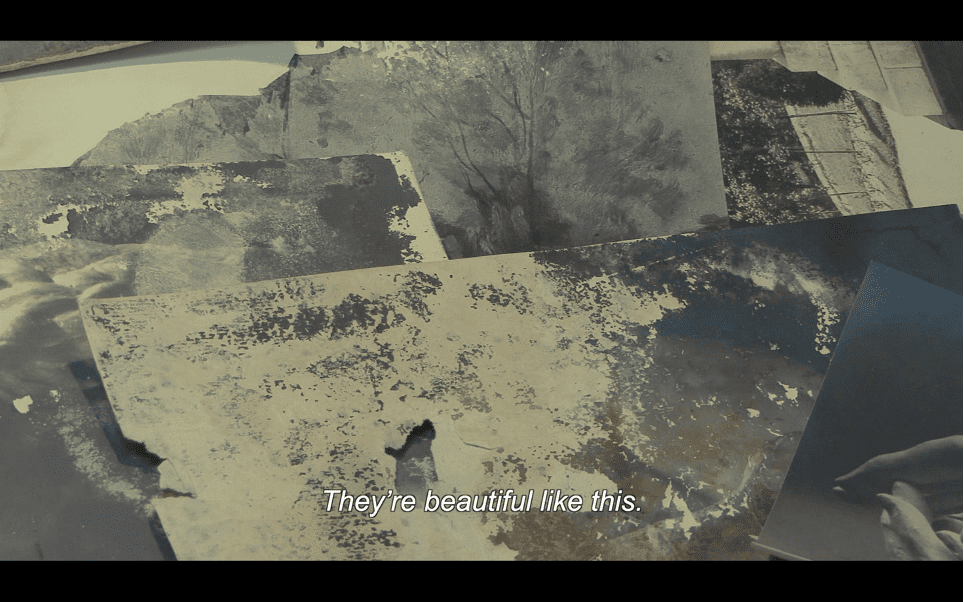

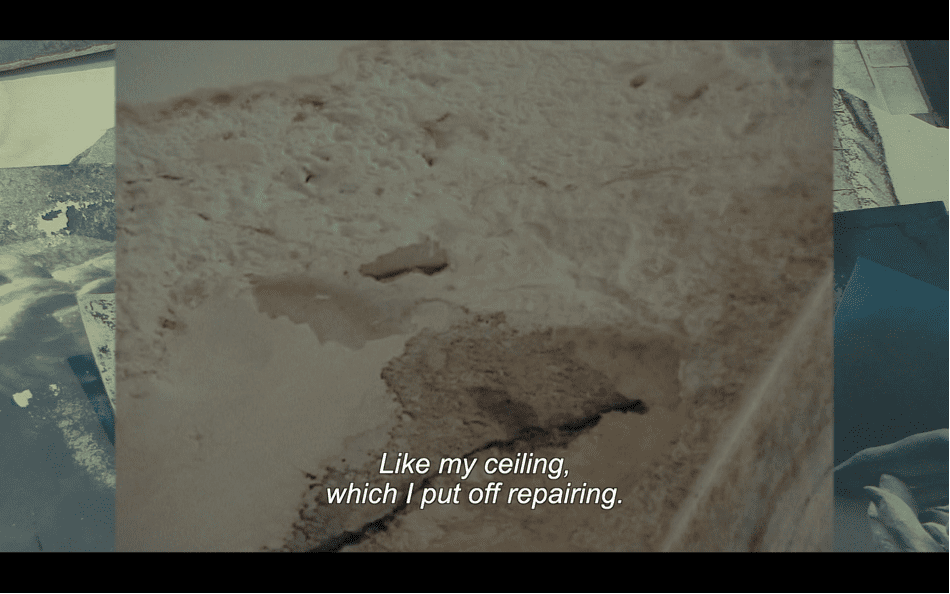

More generally, the core of Varda’s work is delineated by her interest in surfaces and the textures of objects. In Les plages d’Agnès, her fascination with surfaces, their textures, and appearances is highlighted in the scene when Agnès recalls her enrolment at the École de Vaugirard, where she met Demy and began an apprenticeship restoring photographic prints. She explains finding beauty in damaged surfaces, accounting for her refusal to repair the water-damaged ceiling of her own home (Figs. 7-8). Just as the cinematic image contains the marks of time passing, temporal wear and tear are crucial for Varda since they incorporate time.

Figs. 7-8: Agnès compares deteriorating photos to her water-stained roof in Les plages d’Agnès (2008).

Figs. 7-8: Agnès compares deteriorating photos to her water-stained roof in Les plages d’Agnès (2008).

Visages Villages: The Eye of Agnès

In one scene in Visages Villages, Agnès tells street artist JR, that she wants to paste a photo of the naked Guy Bourdin on the ruins of a building. Pasting a ruin on a ruin would have created an image-en-abyme, she explains to JR, who remains unconvinced. In Normandy Agnès decides to visit a house under construction, which has holes for windows, as a possible location upon which to paste Bourdin’s picture. As the team approaches the house, JR jokes that despite being in Normandy, one of the oldest regions in France with many architectural wonders, Agnès is still set on pasting the image on an ugly building under construction. The photo is finally pasted on a WW2 bunker that fell off a cliff onto a beach. The next day, the image has been washed away by the morning tide.

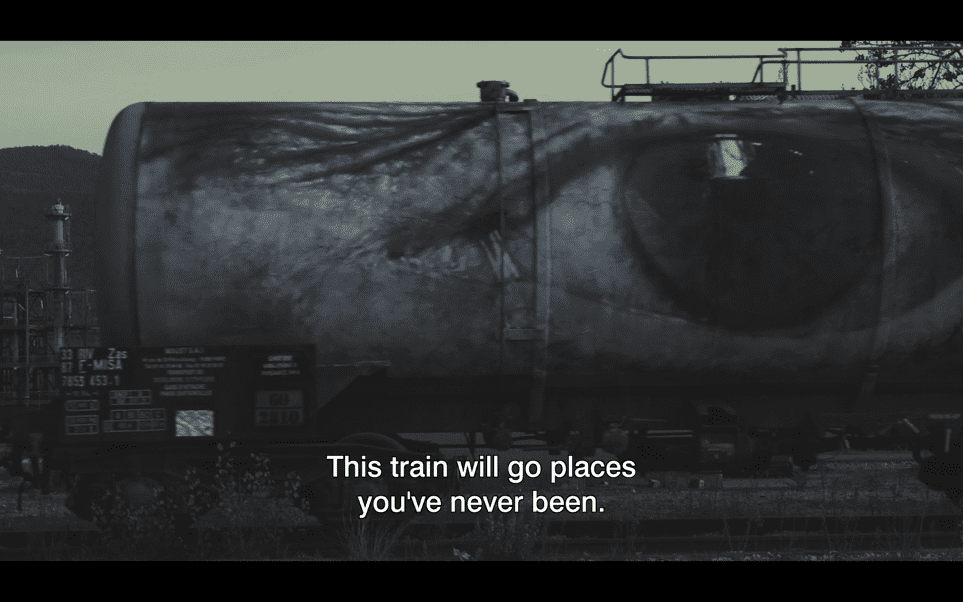

Agnès’ initial insistence on pasting Guy’s photo on ruins befits her fascination with ruined surfaces, decay, and preservation. It also reflects the importance of the texture of the image. Pasting an enlarged (and ephemeral) image onto a surface is to project it into a given space, adding to the texture of the existing canvas or, in this case, the building’s façade. The tactility of the image is thus transformed by the surface of its canvas. At the end of the film, when Agnès and JR exchange gifts, she takes him to Rolle in Switzerland to meet Jean-Luc Godard. JR gives her blown-up images of her eyes and toes, pasted on the surface of a train (Fig. 9) to enable her fragmented body to travel and reach places she can no longer visit. She compares the shape of her feet to the heart-shaped potato she gleaned from Les glaneurs, the documentary which led to various photographic exhibitions and art installations in Europe. [8]

Fig. 9: Blown-up image of Agnès’ eye pasted on the exterior of a train in Visages Villages (2017).

Fig. 9: Blown-up image of Agnès’ eye pasted on the exterior of a train in Visages Villages (2017).

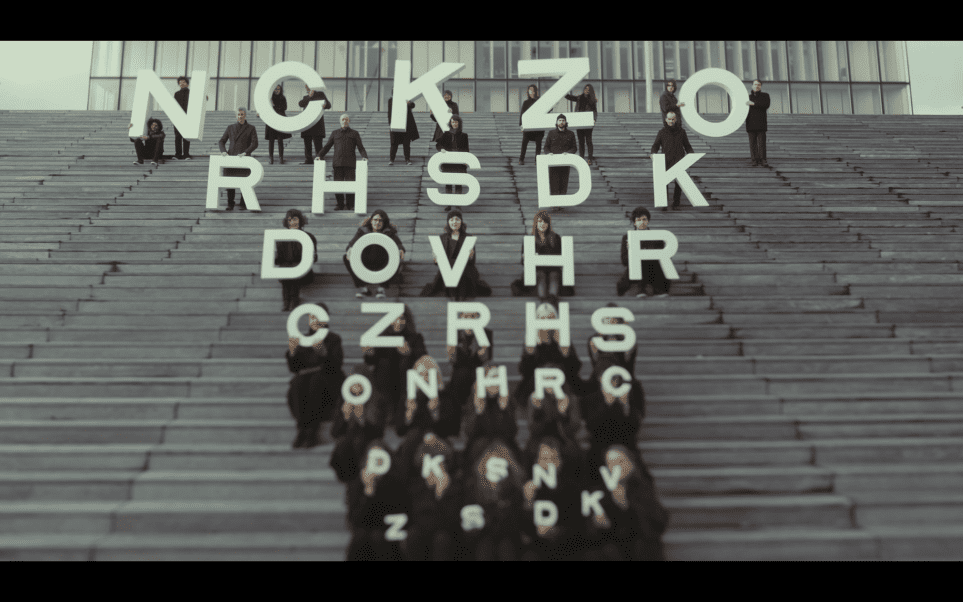

The main focus of Visages Villages is Agnès’ diminishing vision. Thirty minutes into the film, she admits suffering from glaucoma, and we follow her to the hospital where she receives eye injections. With the help of JR, Agnès re-enacts her own vision test in the film, and we see‒through the blurring of the small letters and the small, trembling movements made by the extras holding up large block letters‒ the re-enactment of Agnès’ blurred eyesight (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10: Agnès’ vision test in Visages Villages (2017).

Fig. 10: Agnès’ vision test in Visages Villages (2017).

Although vision is the main focus of these two scenes, the tactility of the image and the temporal representation of its surface remain central as the viewer sees the profilmic image from Agnès’ point of view. Being blurred, the texture of the image is inaccessible, and the spectator is unable to touch the texture of the image just as Agnès is unable to see clearly. Viewers embody her point of view, and, like an unfocused camera, we are unable to capture the fleeting image. Like Guy’s ephemeral image pasted on the bunker, Varda shows us the ephemerality of time (and of her own youth) in these images and the need for a camera to capture these moments that elude her. The real gift, however, appears at the end of the film when JR removes his glasses, which Varda described earlier as ‘dark screens’ keeping them apart (Fig. 11). She remains unable to capture his face clearly, just as she was unable to capture the trucks passing by on the highway in Les glaneurs. Both images present the texture of time and the inability to capture it without cinema’s intervention.

Fig. 11: JR’s blurry face in Visages Villages (2017).

Fig. 11: JR’s blurry face in Visages Villages (2017).

Conclusion: The Feminist Essay Film

The essay film is both embodiment and disembodiment. It is, arguably, a tool of self-deconstruction in its attempt to capture the totality of the framed subject by focusing on its fragments. Varda’s use of the extreme close-up is therefore a technique through which the fragmentation of the body is achieved, as well as a technique that can be associated with the essayistic within the cinematic context. The essay film relies on the extreme close-up to establish an emotional and physical link with the framed subject in a haptic manner, allowing the spectator to feel the traces of a temporal past–to touch a memory.

Varda’s essay films display their status as films. They abound with references to cinema and filmmaking, such as actors re-enacting her memories in Les plages d’Agnès, and Varda looking at herself and reflecting on her artistic achievements in Visages Villages and Varda par Agnès. She associates self-discovery and self-understanding with the creation of a film, so that the end product reflects the essayist’s constructed body. When Varda discusses her fascination with mosaics whilst her employees set up an art installation of her photos in mosaic form in Les plages d’Agnès, the mise-en-abyme shows how the making of a film and the process of constructing the self always involve the act of piecing something together, like making a mosaic. Varda frequently returns to this type of mise-en-abyme in her essay films, all of which highlight cinema as a temporal medium and focus on the process of shooting and editing a film.

In recent years, the essay film, especially the type of self-portrait essay film discussed in this article, has increasingly become a format through which female directors have expressed their own subjectivities on film through the literal framing of their own bodies as the very material of the film itself. Varda has achieved this prolifically, projecting her own body in her films via intimate close-ups to represent the parallels between biological and cinematic time. Through the term ‘feminist essay film,’ the essayistic is arguably reappropriated by predominantly female filmmakers to express their subjectivity as female subjects in their own cinema, in which their cinema portrays and adopts their perspective as women. In the case of Varda, the extremity of this perspective extends to the representation of the director’s own body as her cinema, in which her essay films represent disembodied body parts that altogether form a separate cinematic corpus. Varda’s influence carries much weight and reputation, as traces of her framing her own body in close-ups can be found in the cinema of Alina Marazzi and Naomi Kawase, who have both employed the essayistic in documentaries about their own lives. [9]

Marazzi’s Un’ora sola ti vorrei (For One More Hour with You) (2022) tells the story of her mother, who committed suicide when Marazzi was seven, using archival footage as well as footage shot by her grandfather with a camcorder. However, rather than focusing on the female body framed in close-up, Marazzi’s film focuses on extreme close-ups of the director’s handwritten letters to her mother. Like Varda’s essayistic autobiographical documentaries, Marazzi’s film is essayistic and autobiographical, presenting a mise-en-abyme of her own life history through close-ups of letters and records of medical examinations and treatments undergone by her mother prior to her death. Whilst it does not show bodies, Marazzi’s film is evocative of Varda’s ‘carnal cinematography,’ as both directors treat the cinematic image as an extension of the directors’ memories and bodies. The extreme close-up is employed to frame the tactility and temporality of the surface of both the framed object and the cinematic image itself. The female body and its extensions in the form of letters and documents become the temporal canvas on which they inscribe their subjectivities and identities.

In reframing Varda, this article has reconsidered how her feminist approach to the essay film is rooted in a corporeal, biological perspective whereby the auteur interweaves her body into the creation of her own cinema by employing her own body as the departing point through which to reflect on her personal life and career accomplishments. While other prolific directors, such as Nanni Moretti in Caro diario (1993), have employed a similar approach by making their own bodies and corporeal ailments into the main subject of their films, Varda takes her corporeal representation a step further by treating her films literally as a separate corpus that mirrors her physical form. If Les glaneurs are the hands in Varda’s filmography, then Visages Villages are her eyes. This aesthetic reconstruction of her own biological body through a reflection of the films she has made over the years represents a uniquely feminist approach in using her body as the platform through which to establish her ethos as a prolific director in the male-dominated context of French post-war filmmakers.

Notes:

[1] For a more thorough discussion of the association between the Left Bank Group and the essay film (Corrigan 2008: 41-61 & Corrigan 2011: 8 & 50-75).

[2] For a discussion of Francophone women’s essay film, see, for example, Monterrubio Ibáñez 2023.

[3] While Varda par Agnès was not originally released as a film but a two-part television special, I refer to the work as a film, as following its release, it was subsequently shown as a single feature film in some venues.

[4] Timothy Corrigan’s list of films that shaped the history of the essay film include Alain Resnais’ Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog, 1956) and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967) by Jean-Luc Godard (2011: 36, 58 & 63-64). Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues states that the use of the term ‘essai’ goes back to the 1920s with Eisenstein and was used by Hans Richter in 1940. Liandrat-Guigues notes that in October 1965, Godard described Pierrot le fou (1965) as an ‘essai de film,’ interpretable both as ‘filmic essay’ or literally as an ‘attempt of a film’ (2004: 8-9). Laura Rascaroli further remarks that the first mention of the term was traced back to a 1927 written note by Eisenstein on his own work about the filming of Das Kapital (2017: 2).

[5] Laura Rascaroli also writes about the ability of essay film to challenge the spectator intellectually as an individual rather than collectively as part of an audience (2009: 5-36).

[6] Corrigan also discusses the ‘disembodiment’ of the body present in Varda’s cinema (2011: 73).

[7] Varda’s emphasis on the naked body and the female body is also a topos of her cinema. Earlier films such as L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958) and Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965) include numerous shots of naked women, as well as—especially in Le bonheur—a geometric framing of the body emphasising the female shape. Emma Wilson notes Varda’s fascination with framing human flesh in close-up (Wilson 2019: 48-49).

[8] See Varda’s exhibition ‘Patates & compagnie’ at the Musée d’Ixelles in Belgium and LUX Scène Nationale in Valence, France (2016) which included an installation with six hundred kilogrammes of potatoes. Other film essayists curated art installations derived from their films: Chris Marker (1990-2008); Chantal Akerman from 1995; Godard (2006). For Conway, the language of art installations is influential in Varda’s filmmaking (Conway 2015: 89-109).

[9] For a discussion of how Naomi Kawase represents her own body in her earlier films (Tuan 2022: 285-307).

REFERENCES

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), ‘Cinécriture and Originality’, in The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, New York: Columbia University Press (Directors’ Cut), pp. 111-137.

Conway, Kelley (2015), Agnès Varda, Champaign: University of Illinois Press (Contemporary Film Directors).

Corrigan, Timothy (2008), ‘“The Forgotten Image between Two Shots”: Photos, Photograms, and the Essayistic’, in Karen Redrobe & Jean Ma (eds), Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography, Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 41-61.

Corrigan, Timothy (2011), The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker, New York: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David Oscar (2012), ‘The Limits of Vococentrism: Chris Marker, Hans Richter and the Essay Film’, SubStance, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 6-23.

Ince, Kate (2013), ‘Feminist Phenomenology and the Film World of Agnès Varda’, Hypatia, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 602-617.

Liandrat-Guigues, Suzanne (2004), ‘Un art de l’équilibre’, in Diane Arnaud, Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues, and Murielle Gagnebin (eds), L’essai et le cinéma, Seyssel: Éditions Champ Vallon (L’Or d’Atalante).

Lopate, Philip (1992), ‘In Search of the Centaur: The Essay-Film’, The Threepenny Review, No. 48, pp. 19-22.

Monterrubio Ibáñez, Lourdes (2023), ‘Women’s Essay Films in Francophone Europe. Exploring the Female Audiovisual Thinking Process’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, pp. 1-35.

Moure, José (2004), ‘Essai de définition de l’essai au cinéma’, in Suzanne

Liandrat-Guigues & Murielle Gagnebin (eds) (2004), L’essai et le cinéma, Editions Champ Vallon, pp. 25-40.

Önen, Naz (2019), ‘Essay Film as a Dialogical Form’, JOMEC Journal: Journalism, Media, and Cultural Studies, No. 13, pp. 93-103.

Rascaroli, Laura (2008), ‘The Essay Film: Problems, Definitions, Textual Commitments’, Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 24-47.

Rascaroli, Laura (2009), The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film, New York, NY: Wallflower Press.

Rascaroli, Laura (2017), How the Essay Film Thinks, New York: Oxford University Press.

Rascaroli, Laura (2020), ‘Compounding the Lyric Essay Film: Towards a Theory of Poetic Counter-Narrative’, in Julia Vassilieva & Deane Williams (eds), Beyond the Essay Film: Subjectivity, Textuality and Technology, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 75-94.

Rosello, Mireille (2001), ‘Agnès Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse: Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady’, Studies in French Cinema, Vol, 1, No. 1, pp. 29-36.

Stob, Jennifer (2022), ‘Agnès Varda’s Formalist Feminism’, in Colleen Kennedy-Karpat & Feride Çiçekoglu (eds), The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda: Feminist Practice and Pedagogy, Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 15-28.

Tuan, Lydia (2022), ‘The Matter of Manual Traces: Letters, Photographs and Bean Paste in Naomi Kawase’s Cinema of Touch’, Film-Philosophy, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 285-307.

Wilson, Emma (2019), The Reclining Nude: Agnès Varda, Catherine Breillat, and Nan Goldin, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Films

Caro diaro (Dear Diary) (1993), dir. Nanni Moretti.

Jacquot de Nantes (1991), dir Agnès Varda.

L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse… deux ans après (The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later) (2002), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008), dir. Agnès Varda.

Un’ora sola ti vorrei (For One More Hour with You) (2002), dir. Alina Marazzi.

Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), dir. Agnès Varda.

Visages Villages (Faces Places) (2017), dir. Agnès Varda.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey