The Sunflower’s Redemption: Agnès Varda’s Life & Art

by: Sandy Flitterman-Lewis , November 7, 2023

by: Sandy Flitterman-Lewis , November 7, 2023

‘I don’t believe in aging. I believe in forever altering one’s aspect to the sun’. (Virginia Woolf 1965: 187).

*

Agnès Varda’s third feature, Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965), was—and continues to be—her most controversial film, mostly due to the misapprehension of its lyrical irony and joyful cynicism. She says that she thought of the Impressionist painters (and there is stunning evidence of this in the vibrant pastoral compositions), as artists who, in their melancholy painted happy scenes. And the Mozart-accompanied images of delightful picnics and happy outings for this family of four, awash in sunflowers and vivid natural landscapes, do just that. But the husband has an affair and then explains to his wife how his happiness has doubled, and she drowns in the beautiful lake. The family of four’s outings then continue in autumnal hues, with the lover replacing the wife. Viewers who failed to understand the sharp critique of bourgeois marriage assailed Varda for praising that very institution. An unfortunate feminist misreading, often proposed by prominent scholars at the time, interpreted the husband’s actions literally and uncritically, taking his avowal of ‘double happiness’ as the filmmaker’s point of view. But any recognition of Varda’s ironic strategies will understand that the resulting replacement of the wife by the lover (household chores included) signals a bitter recognition of patriarchal power and its ability to destroy women’s lives. As Varda characteristically says that it’s like ‘une pêche de plein été avec ses couleurs parfaites, mais dedans il y a un ver’ (a summer peach with its perfect colours, but inside there’s a worm) (Varda 1998). And she has the last laugh, as the sumptuous images of Le bonheur’s sunflowers have become an icon of Varda’s film career, so much so that one of her final installations (her third phase, as a visual artist, as she prefers to be called) is a cabane (shack) made of the discarded 35-millimetre films, filled with brilliant artificial sunflowers, which are now seen as a sign of her resilience and powerful beauty.

My suggestion of the sunflower’s trajectory in Varda’s career is also a way of understanding her unique blend of personal testament, documentary material, fictional composition, and social vision. Sometimes these strategies are mixed in a single work (as in Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) [1985] or, arguably, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse (The gleaners and I) (2000), and sometimes they are divided among separate compositions that can be read in tandem (as in the double collage/ portrait Jane B. par Agnès V. (Jane B. by Agnès V.) (1988) and the disastrous Le petit amour (Kung-fu Master!) (1988), or the Los Angeles duo Mur murs (1981)—a pun on ‘walls’ and ‘whispers’—and Documenteur (1981)—which Varda subtitled as ‘an emotion picture’. Sometimes a fiction is constructed around a pressing contemporary social issue, as in L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t) (1977) (excruciatingly relevant in these devastating times), and sometimes Varda invents a new autobiographical form that combines innovative revisitings with cinematic clips, bits of wisdom, and comments on aesthetic theory, as in Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008) or Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), the title of which is taken from the 1994 book which began this project at mid-career and demonstrates Varda’s uncanny kind of foresight.

Varda’s Voice

Strategies of self-representation have always been a hallmark of Varda’s art. It is this distinctive personal voice, one that transcends mere subjectivity, that has persevered over the years, through her various invented forms as she has renovated cinematic language (a principal tenet of the New Wave, the Boys’ Club from which she was often excluded), redefined the nature of cinematic documentary—a preferred form for Varda—and expanded the notion of visual art in her later installations, autobiographical films, and masterclasses (although she typically likes to call them ‘conversations’). Parenthetically, this last avatar of her personal voice, her fifteen years as a visual artist, carries within it her earliest artistic expression, photography. The mix of registers—the social, the cultural, political, and the personal—has always intrigued Varda, and these are what transform her autobiography into broader cultural statements. But the personal aspect is always there—a generative force that explores the world around her and produces ever-evolving visual and aesthetic forms. ‘People are at the heart of my work. Real people,’ she maintains, describing the double movement between self and other that grounds her cinematic and artistic practice (Varda 2019-20). The sunflower traces the undeniable and unique assertion of self, Agnès Varda’s complex identity as an artist and as a woman. As I say in To Desire Differently, ‘[Varda’s] effort not only to constantly articulate challenges to dominant representations of femininity, but also to express what it means to see—to film—as a woman, means that a profound feminist inquiry is at the centre of all her work’ (Flitterman-Lewis 1996: 264). There is a tenuous but essential balance here: Varda continually associates her expansive film work with her identity in a dialectical movement that enriches both. As she stated as early as 1975, ‘finding one’s identity as a woman is a difficult thing: in society, in private life, in one’s body. This search for identity has a certain meaning for a woman filmmaker: it is also a search for a way of filming as a woman (filmer en femme)’ (Varda 1975: 46). The sunflower, abundant in Varda’s third fiction feature, becomes a leitmotif in her last works, down to the pervasive golden yellow that brightens the slipcase of the Criterion DVD box set and forms the last of the ‘cinema shacks’ that populate her third phase as a visual artist. The sunflower thus signals the permutations/ transformations of self and art that traverse her six-decade career.

Le bonheur sits firmly within the category of Varda’s ‘first fiction films,’ situated between, on the one hand, two inaugural features—the radically experimental La Pointe Courte (1955) and the dazzling Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962)—and on the other, what she considers a misunderstood failure—the fractured fairy tale of Les créatures (The Creatures) (1966). As such, we can consider Le bonheur exemplary of her fiction film phase, and the sunflower as symbolic of her desire to reaffirm the representational capacity of cinematic discourse. The film, a well-constructed circular narrative, uses sunflowers to provide the authenticating pastoral background while augmenting the seductive natural beauty of the setting, something that functions as ironic commentary on the idyll. In fact, the exaggerated brilliance of these blooms paradoxically works as both a naturalising feature and a distancing device. It establishes a primary element in Varda’s cinematic language, as she goes on to create multi-layered narratives that engage elements of the objective documentary world in philosophical, metaphoric, aesthetic, and meditative constructs that far exceed the literal representation of stories.

Four decades later, after a rich period of experimentation with different intersections of narrative and documentary, each with a variation on the process of personal intervention, Varda embarked on what she called the ‘third phase’ of her career, as a visual artist and creator of installations. Dominique Bluher, a close friend for decades (she even knits Varda a purple sweater in one episode of Agnès de ci de là Varda [2011]), summarises this ‘Third Life’ in this way: ‘[T]his last creative period, which Varda began at the age of 75 at the Venice Biennale, shows photographs, films, and video formats that Varda combined to create cross-media installations … [demonstrating her] joy of media play and experimentation’ (Bluher 2022). And it is here that Varda re-envisions and realises an often-asserted lifelong dream of articulating documentary and fiction in a single work. Three-dimensional autonomous structures involving video projections, scenic innovations, and new forms of audience invocation allowed for the objective (and material) documentary world to engage with artistic structures. It is also the very radical way in which Varda inserts herself into these constructions, creating a new understanding of the personal and of authorship itself. In over twenty large-scale installations and numerous smaller ones, plus new photographic works and repurposed older ones, Varda energetically expanded the parameters of her artistic vision and redefined artist-spectator relations by creating participatory works in three dimensions. As Kelley Conway notes in her excellent video essay in the Criterion DVD box set, Varda has always loved to interact with her audience, and installations provide ‘a new cultural marketplace,’ the perfect locus of exchange for which the films had laid the groundwork (Conway 2020). Each installation requires an active form of viewing, as the somewhat passive recipient of images in the theatre is transformed into an interactive, questioning, engaged participant. From the papier-mâché potato costume that allowed Varda to mingle with the gallery guests in her first installation, Patatutopia (2003), to the meditation on loss and memory in Les veuves de Noirmoutier (The Widows of Noirmoutier) (2006), to the solemn evocation of the silent heroism of Les Justes au Panthéon (2007), these installations both harken back to the early pioneering force of La Pointe Courte and project into the future with a sense of her ongoing, irrepressible creative energy, her refined sense of social engagement, and her desire to share both of these.

And thus, we return to Le bonheur’s sunflowers, finding their renewed significance in this twenty-first century form. Agnès Varda’s very last installation prioritises sunflowers as they become associated with this third phase and thus with both a reminiscence and a certain kind of culmination of her lifetime of artistic practice. As she describes the cabane/ film hut/ shack [1] constructed of discarded 35mm film of Le bonheur and filled with potted sunflowers she says:

My nostalgia for 35mm cinema films turned into a desire to recycle them… I build huts with abandoned copies of my films… They’ve become huts, favourite houses of an imaginary world… This is the third hut I’ve built. I imagine a specific form for each of my films. Le bonheur was made in 1964 and told the story of a happy family, played by Jean-Claude Drouot, his wife, and children [an aside: real people in a fictive world]. They liked picnics. (Varda 2019).

She continues, ‘I shot the film in Ile-de-France with Impressionist painters in mind. The music was by Mozart. The credits were shot near a field full of sunflowers, flowers redolent of summertime and happiness.’ (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Sunflowers and summertime in Le bonheur (1965).

Fig. 1: Sunflowers and summertime in Le bonheur (1965).

She goes on to say:

I made this greenhouse with its special double windows out of a complete copy of the film. … Visitors will be able to go inside and see the film’s transparent images close up … You’re surrounded by the film’s duration and images of a time long past … Is this nostalgia again or recycling? A royal arch made of empty 35mm film boxes invites us to make our way into the kingdom of the second life of films. (Varda 2019) (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Shack of Happiness (Programme 15, Supplements: Installations #9 2009-2019: 1:00:30-1:04:42).

Fig. 2: Shack of Happiness (Programme 15, Supplements: Installations #9 2009-2019: 1:00:30-1:04:42).

Varda thus cleverly uses the past to evolve an art of the future; her protean creative self guides us into a new generation of image-making, and thus has the power to endure in our imaginations. The cinema shacks do indeed create worlds as Varda embraces the transitions of time before our eyes.

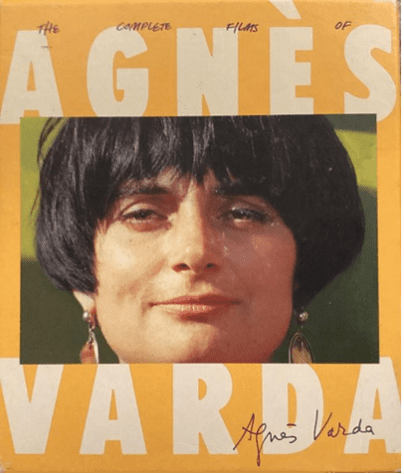

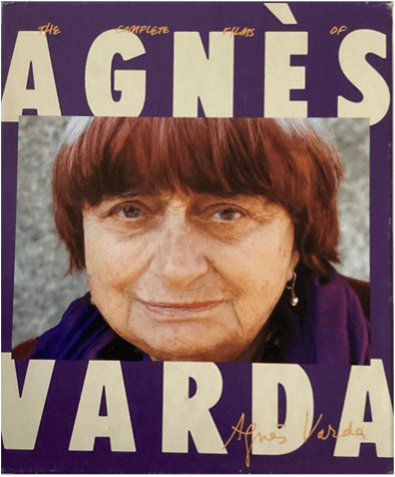

Varda’s authorial process of continuity and transformation is imaginatively represented by the Criterion DVD box set slipcase (2020). It features two portraits of Varda, one on either side of the box: Young Varda framed in sunflower gold—a photo that she and daughter Rosalie call ‘chic moderne’—on the one side, and octogenarian Varda, framed in Vardian purple—now referred to by others as ‘diminutive,’ and ‘charming’—on the other (Fig. 3). Put another way, we have the Agnès of Oncle Yanco (Uncle Yanco) (1967), full of fun and exploration, and the Agnès of The Beaches of Agnès, contemplative and joyfully self-ironic, with lessons learned from a lifetime of creative engagement.

Fig. 3: Portraits of Agnès Varda on both sides of the Criterion DVD box set slipcase: Uncle Yanco ©1967 Ciné-tamaris (upper); photograph by Mathieu Demy © Ciné-tamaris (lower).

Fig. 3: Portraits of Agnès Varda on both sides of the Criterion DVD box set slipcase: Uncle Yanco ©1967 Ciné-tamaris (upper); photograph by Mathieu Demy © Ciné-tamaris (lower).

In a sense the box set’s definitive collection demonstrates Varda’s foresight in providing newer generations of viewers a roadmap through her career, and seasoned veterans the opportunity to revisit and reimagine old cinematic friends. Just as Cléo’s trajectory through Paris (that takes the shape of the human heart) gave us a dazzling new view of the City of Light (most of the film takes place outdoors in public spaces), Criterion’s box set gives us a luminous and comprehensive pathway through the productive genius of our effervescent pioneer. And the sunflower traces this trajectory as well, as we see Varda repurposing its iconic presence in both the early fiction film and in her final installation.

Happiness

Indeed, Varda had already presented her own timely reassessment of Le bonheur in Criterion’s earlier box set, Four by Agnès Varda (2007), where, as preface to Amy Taubin’s essay, she re-evaluates her initial statements about the film in light of its retrospectively considered irony. In 1965, ever the companion to the presentation of her films, Varda stated, somewhat provocatively, ‘This film is a day in the country in which love and picnics have great importance. But children do as well, because it’s about a family where happiness can’t be conceived of without children’ (Varda 2007). And although the film eventually establishes a conflict between the happy family and pernicious male desire (whence the critique), all familial happiness does seem to revolve around the children. Domesticity itself is meaningless without the flurry of repetitive activity involving the kids. In this film they hold a central role in the maintenance of happy familial relations. (Parenthetically, note that the lover, Emilie, is depicted in abstract modernist spaces—white walls, and angular shelves—until she becomes Thérèse’s replacement, and the household chores begin again). And yet, despite what I see as early limitations, the sentiment about children (and family) is one that Varda seriously champions for the entirety of her career. She does this with the same kind of revisioning we see in Mary Cassatt, for example, whose portraits of mothers and children defy the romanticising patriarchal view of the subject. For its 1965 inauguration Varda continues, ‘I would like this film to make the viewer think about “the vivid brightness of our short-lived summers” and about the Impressionists. In their paintings, there is a vibration of colour that seems to me to correspond to a certain idea of happiness’ (Varda 2007). Here we have the Agnès of art history, her acute sensitivity to the formal characteristics of oil painting through the ages, and a purely material justification for the visual excess of the film. ‘But,’ she adds, suggesting her simultaneous awareness of the underlying critique of bourgeois marriage and male desire:

I will also respond with other formulas: ‘Happiness is mistaken sadness,’ and the film will be subversive in its great sweetness … Happiness adds up; torment does too. ‘Happiness is not gay:’ these are the words we hear at the end of Max Ophüls’s Le Plaisir. (Varda 2007)

These words were later adapted by such melodrama revisionists as Fassbinder, Godard, Sirk, and Haynes. In the same booklet, now writing in 2006, Varda adds an addendum:

I reread what I wrote, here and there, about Le bonheur. I will add that when asked why Mozart, I would say that his happy music was heart-wrenching. I read the critics of Le bonheur, those from the sixties and from the nineties. It seems as if they are discussing a film that has grown away from me, even if its topic remains true (what does one do about the other’s desire?), and its treatment fits the storytelling (with different colour palettes); but I feel like I have dropped a bouquet of flowers somewhere, then turned around and walked away. (Varda 2007)

Married Life

By 2019, Varda has turned around yet again with her presentation of Le bonheur in the comprehensive Criterion box set. Here she does not exactly disavow the film, but rather begins to tease out the contextualising relations that will reverberate in the valedictory context of this collection. Three films about couples are found in programme 5 ‘Married Life’: Le bonheur (1964), Les créatures (1966), and Elsa la rose (1965), thus putting into productive dialogue one popular but controversial film, one perceived failure, and one tender, poetic documentary that had been hard to see for a long time. Significantly, in the context of my study here, two of these films sit in dialectical relation to each other in the ‘third life’ of Varda’s creative project. An early ‘film hut’ constructed of 35mm film strips and called the ‘Cabane de l’Ėchec’ (The Shack of Failure) repurposes Les créatures and gives it new life near the start of her career as an installation artist. And, as I have noted above, the ‘Serre du bonheur’ (The Greenhouse of Happiness) is built of 35mm strips of Le bonheur. The two versions of marriage in the programme ‘Married Life’ reassert themselves in this modern, reflexive form, and, as is typical of Varda, allow for renewed discussion and contemplation of life-defining issues. Their presence in the catalogue of ‘film shacks’ engenders a rereading of each film, such that earlier interpretations (a failure, and a vexed celebration of domesticity) become complex rewritings of the films in relation—the dialectic of the shacks, so to speak.

In addition, in this programme 5 there is also a number of richly provocative supplements, most, if not all, taken from the earlier 2007 Criterion quartet:

1) Varda’s 1998 introduction to the film, made for ARTE’s television emission, in which she discusses the production of a new negative that restores the brilliant colours, and she makes the defining statement: ‘With all the prefabricated images of happiness in the media, it’s worthwhile deconstructing the clichés’ (Varda 2020). [2]

2) ‘Two Women of Le bonheur’ (2006) in which Rosalie remembers the film with the two female principals, Marie-France Boyer and Claire Drouot (‘The film helped us keep a sense of humour about things,’ says Drouot of their enduring 45-year marriage).

3) ‘Thoughts on Le bonheur,’ a sequence that brings together four critical thinkers (a journalist, a producer, a film critic, and a feminist activist) in 2006 to discuss their thoughts about the film and about happiness as a concept—exactly the kind of conversation that Varda delights in—unwittingly revealing the huge differences in perception between men and women, and the surprising formulation of ‘Chromatic Logic’ that structures the film.

4) Two short fanciful documentaries, one in which ‘The people of Fontenay respond to the question: What is Happiness? (une enquête [survey] that re-envisions another New Wave staple, Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s 1961 Chronique d’un été), and another (‘Bonheur: Proper Noun or Concept?’) in which definitions by great writers conclude with Varda writing on her courtyard wall a phrase by French poet Louis Aragon: ‘Qui parle du bonheur a souvent les yeux tristes’ (who speaks of happiness often has sad eyes) (Aragon 1967).

Here, even in this relatively early introduction from 1998, Varda is already suggesting the third part of the triad in ‘Married Life’ by bringing the poet and his love poem (‘What Would I Be Without You?’) (Aragon 1967) into this early meditation on happiness and introducing into the discussion an intriguing poetic statement that engages us in complex thought.

Two more supplements round off programme 5 and once again we are taken on a voyage through time. In supplement 5, ‘Jean-Claude Drouot Returns to Fontenay aux Roses,’ the fictional husband (and hero of the 1960s popular television series Thierry La Fronde), still handsome, but in a rugged, aged way, retraces his steps and meets with members of the cast and other locals forty-two years after the film’s production. They reminisce, they joke around, and in a true work of memory they contemplate the film, its characters, and villagers from the distance of years. There is joy, even fellow-feeling, and yet upon consideration of these conversations, the film in fact offers us a fable of masculinity in a feminine voice. Drouot calls it a film about desire (a masculine interpretation to be sure), yet in reality his own marriage has lasted close to fifty years. Agnès speaks fondly of the ‘little family of the tournage’ while Drouot asserts that his memory of the film suspends time. And as viewers of this supplement, we negotiate the differences between the film we have seen and the reality of its production, present, and past—an unlikely exercise for a film that offers up so much frivolity and sumptuous visual beauty.

Supplement 6 has a title that suggests fantasy and adventure, ‘Démons et Merveilles du Cinéma.’ However it is quite the opposite: in fact it represents the documentary spontaneity of a portion of a 1964 television programme directed by Jean-Claude Bergeret. Here we are on the set of Le bonheur with young Varda, who, in directly addressing the camera, speaks about the collaborative effort of the shoot: ‘The director doesn’t do anything. [He] has a vision, but the actual work is done by others.’ In other words, the director might go behind the camera, framing the action, organising rehearsals, but the real work is done by this little community. And to the question ‘What is happiness to you?’ she responds, ‘At the moment it’s a film I’m making. Lots of work. Lots of fun’ (5.6. Varda 2020). It is interesting to note that if we substitute ‘installation’ for ‘film’ this statement could be attributed to the later Varda, the visual artist. The energy, the passion, and the recognition of collective work (this can extend to her subjects as well, who are often seen as participants, as in Gleaners or Visages Villages (Faces, Places) [2017]), are all hallmarks of Varda’s embracing aesthetic. And finally, in a kind of haiku of a trailer, Supplement 7 provides us with Mozart, quick scenes of picnics, children, passion, credits, and of course sunflowers. The iconic bloom appears boldly between representative shots and written announcements of the Prix Louis Delluc Award for 1965, the producer Mag Bodard, and the authorial signature, Agnès Varda. I have run through this little catalogue of Supplements that comprise an essential part of programme 5, ‘Married Life,’ to offer some idea of how in this ‘third life’ Varda constructs not only her history, but the joyfully aging, energetic, and ever-creative auteure that she is. I alluded earlier to the way in which Varda builds her history, and the history of her oeuvre, with temporal looping and reassessments that always reveal her feminist project: her effort, as I say, to filmer en femme. With these supplements (that might even act as Talmudic commentary) our readings of the original films are enhanced, remembered, and introduced to new viewers while all the while revealing the transformations of the self that are an integral part of Varda’s art.

Fontenay-Aux-Roses, Noirmoutier, Paris

Early assessments of Le bonheur seem, characteristically, to miss the point, as in Roy Armes’s blinkered formalist description, eschewing the possibility of a feminist reading that was obviously there:

The source of Agnès Varda’s individuality, and the sense of life and vitality one finds in her films, is her training as a photographer… All her films are impeccably shot, with a sharp grasp of detail and a keen interest in a documentary approach, most clearly apparent in the backgrounds of her films … She shows a great sensitivity to tiny variations of light and the atmosphere they produce … and has made a bold and imaginative use of colour (in Le bonheur). Despite her literary interest and tendency to abstraction Varda remains a true filmmaker whose central preoccupation is with seeing. (Armes 1966: 84-5)

Yet despite this patronising description that makes Varda sound like a playful cat with a butterfly toy, Armes cites one of her most oft-quoted phrases, currently used in practically every retrospective and series devoted to her. He just gets the emphasis wrong. Varda states: ‘In my films I always wanted to make people see deeply. I don’t want to show things, but to give people the desire to see’ (Armes 1966: 85). This is not a statement about seeing, but about sharing, and the invocation of desire removes vision from its purely physical status. It can also be read as her aesthetic philosophy. Whether it is about the brilliance of Le bonheur’s dazzling colour scheme or about clochards (tramps) on the rue Mouffetard, Varda always wants us to share with her, to partake of her compassionate vision, to see things differently so that we may perpetually learn.

Because in programme 5 Varda has chosen to group Le bonheur (whose title can be either celebration or ironic undercutting) with Les créatures (a Surrealist fantasy about two types of creation, also suggested by a modified reading of the title as Les créateurs), and Elsa la rose (a love poem about love poems), we must now consider the three films in relation, as each presents a complex and unexpected view of its female characters. All three women are quite complicated beneath their surface readability or the presence of clichés. Thérèse, the perfect loving wife in Le bonheur, exists for the happiness of her beloved husband and their children… until she does not. Her suicide (?) is the only thing that she orchestrates on her own, an act of defiance preceded by her request that François make love to her. As he lolls contentedly under a tree, the picture of satisfaction, Thérèse puts her plan into action. This is what led one critic to remark, ‘The film’s ending is terrifying. It’s a cruel tale’ (Varda 2020). But it is the cruelty of this tale that leads to the feminist interpretation. The resumption of domestic tasks by the lover-turned-wife is all you need to know in order to understand the sharp critique of patriarchy’s institution of marriage and the egotism of masculine desire. As for Les créatures (whose return to the black and white of La Pointe Courte and Cléo de 5 à 7 signals a renewed interest in photography’s palette), the image of the exquisite, icy Catherine Deneuve reduced to silence and brief handwritten notes, suggests that beneath the glacial beauty lies a volcano of turbulent emotions. Meanwhile, her writer husband, responsible for the car crash that has reduced her to silence, wanders the remotely beautiful island of Noirmoutier (here again the black and white cinematography creates an atmosphere that is uncannily haunting) encountering bizarre strangers and incorporating them into his fictions, such that neither he nor we understand which is truth and which is imagination. Both kinds of creation (masculine author’s work and feminine childbirth) culminate in the wife’s delivery of a baby boy, and her resumption of speech. And all is well in this madcap fable of a world. And yet there is an emotional subtext here that justifies the placement of this cinematic failure in the programme called ‘Married Life.’ Noirmoutier, a veritable lieu de mémoire [3], holds a special place in the Varda-Demy love story. It is here that the couple, early in their marriage, chose this wild coastal place to establish a vacation residence, a rugged land of productive joy. Each of them was at work on separate projects, punctuated by long walks on the windy terrain. Varda dedicated Jacquot de Nantes (1991) to Demy, and Noirmoutier is the site they returned to in the magical days of their reconciliation and Demy’s declining health. While Varda’s first cinema shack is called ‘La Cabane de l’Ėchec’ (The Shack of Failure), it is really an energetic renewal of passion—in life, in memory, and in cinema, and thus is now called ‘The Shack of Cinema.’ Varda recalls this in her notes in the pamphlet accompanying The Beaches of Agnès:

Noirmoutier Island. Long walks on the beaches. Shared love and the gift of space. A place of calm and work, facing the ocean. Time to reflect on why and how to be a filmmaker in such a messed-up world … A film in 1966: failure! As a good gleaner and recycler, I salvaged copies of the film. Christophe Vallaux designed a metal structure, and we built a large hut. The walls are made of film. A movie-lovers hut! [4] (Varda 2008: 8)

And now we come to Elsa et la rose, neither documentary nor poetic meditation, but rather a cinematic hybrid through which Elsa, the enduring muse of poet Louis Aragon and winner of the prestigious prix Goncourt, speaks and gently rebels against this stifling definition, with love remaining intact. In this inventive collage that moves back and forth in time, from old Russian photographs of Elsa’s youth to Parisian re-enactments of their first meeting at the Bar du Dôme in Montparnasse in Paris, the poet Aragon imagines Elsa’s childhood, the before-time of their relationship, and then references their first meeting through repetitions of Le Dôme’s revolving door, the lovers now quite old. Stunning in its evocative capacity, with repeated images of the elderly couple (Fig. 4) and Aragon’s incantatory poetry read by actor Michel Piccoli, this is a reflective meditation on time, memory, poetry, and love. All the while, it deconstructs the myths around this legendary couple, adding an unexpected depth to their enduring relationship and lightening the mood with a little bit of laughter. As Varda says in her 2007 introduction in her courtyard, desk set up and a painting of a rose in the background, Aragon’s poetry in the volume Les Yeux d’Elsa (Aragon 1944) is ‘like the indefinable form of laughter’ (5. Varda 2020). She continues speaking of Elsa’s multiple roles noting her fascinating courage in accepting her dual status, the true Elsa, aging gracefully, as companion and accomplice to her husband’s poetry, while she was also the dream Elsa, the poet’s muse and the perfect rose, mythical, and adored. Yet Elsa Triolet was also a prolific writer (seventeen books) who made and sold jewellery, lived the century’s great historic moments, and refused to be defined solely by the poet who loved her. In answer to Varda’s question, ‘With all these poems written for you, does that make you feel loved?’ Elsa responds, ‘No, it’s the rest. Life’ (5. Varda 2020).

Fig. 4: Elsa la Rose: Aragon and Elsa reminisce (Programme 5).

Fig. 4: Elsa la Rose: Aragon and Elsa reminisce (Programme 5).

Cinema Shacks & Other Installations

And so it is that near the end of a six-decade career, Agnès Varda has chosen fifteen years of praxis as a visual artist and added a final punctuation of… SUNFLOWERS. ‘The old cinéaste has become a young visual artist,’ declares Varda in The Beaches of Agnès (15. Varda 2020). As she sits inside her first cinema shack, composed (as noted) of discarded 35mm film stock of Les créatures, alongside stacked film cans, Varda reiterates, ‘What is cinema (echoes of Bazin)? A light source captured by images either dark or colourful. And when I’m here it feels like cinema is the house I live in. It’s like I’ve always lived here’ (15. Varda 2020). Visiting one of these cinema shacks is an extraordinary experience: you are surrounded by celluloid, the images of which you can peruse up close in stasis, while imagining or remembering their projection in their earlier form. Varda has truly deconstructed the cinematic apparatus. Kelley Conway cites Varda’s passion for people and places which, she says:

has allowed [her] to conceive and operate the multiple rooms of the art gallery, adapting her storytelling to fill huge polyvalent spaces and manipulate viewers through the plastic realm of her imagination, which is given shape, brought to life, or cobbled, recycled, and reconstructed from found objects, recovered footage, and reimagined memories.’ (Conway 2015: 123)

For her final installation Varda has added potted sunflowers, a forest of gleaming blooms that surround viewer-participants as they enter this magical space. In his notes to another edition of The Beaches of Agnès art critic Luc Vancheri questions how a series of segments from a film reel in the shape of a shack manage to maintain both the film itself, and projected cinema at the same time. He argues that since light is passing through the physical celluloid of the film stock, the film is still being projected and revealing its hidden images. The viewer of the shack has the choice of examining the images themselves or the light that is being refracted and filtered through the celluloid (Vancheri 2010). This is indeed a summary that would make Varda proud, as her aim, it seems, is to give her viewers yet another kind of experience of the cinema while retaining its essential elements.

Varda’s self-presentation, a hallmark of her innovative cinécriture, is perhaps most evident in The Beaches of Agnès as she takes us through her life and career in a typically imaginative way, a cinematic puzzle (a word she likes to use to describe her collage-like constructions). The elegance of Michael Koresky’s assessment at the end of his remarks on programme 15 The Beaches of Agnès allows us particular insight into the functioning of these Cinema Shacks:

There are even ghosts here representing the materiality of film itself. Near the end of The Beaches of Agnès, Varda shows off her ‘cinema shacks.’ When the light streams through them, it is as though cinema has been reborn. Always gleaning and repurposing, whether in terms of physical formats or images or genres or modes of expression—Varda allowed us to see film as the endlessly regenerative form that it is. Whether making movies explicitly about her life or creating fanciful worlds, she gave us the privilege of seeing through her eyes.’ (Koresky 2020)

Varda’s ‘I’

Here Virginia Woolf, that patroness of women’s self-expression, returns to us. Earlier I alluded to the fact that Varda’s subjective voice was very different from that celebrated by her male compatriots. Her personal voice, everywhere apparent in the three phases of her artistic production, and always expressed in the social terms of dialogue and connection, diverges widely from the ‘masculine singular’ of the New Wave band of brothers (Sellier 2008). For them, the personal mode of expression provided a vehicle for romantic longing, for nostalgia, and for a way of claiming a universal centrality for their subjective experience. On the other hand, Varda’s personal voice is socially constructed, mediated by the countless other voices she engages across the range of her films, her travels, and her encounters. Woolf describes the shadow of the ego in literature this way:

[But] after reading a chapter or two a shadow seemed to lie across the page. It was a straight dark bar, a shadow shaped something like the letter ‘I.’ One began dodging this way and that to catch a glimpse of the landscape behind it. Whether that was indeed a tree or a woman walking I was not quite sure. Back one was always hailed to the letter ‘I.’ (Woolf 1965: 1987)

You can see this shadow in the cinema of the New Wave through François Truffaut’s celebratory prediction of 1957: ‘The film of tomorrow seems to me even more personal than a novel, individual, and autobiographical, like a confession or a private diary’ (cited in Armes 1966: 5). By the late fifties Varda had already engaged in a cinema that demonstrated her personal stamp, but it was through original invention, the assertion of a female voice, and an attention to those ignored by the grand topics of the current cinema. This curiosity, that endured the entire six decades of her career, went beyond the borders of the self to redefine authorship in social terms. Geneviève Sellier cites an important early observation of Varda’s: ‘I believe in encounters. According to their possibilities, people meet for an instant, a minute, or a lifetime… Everyone, one way or another, needs it. Those who know it are already less unhappy than those who don’t’ (Sellier 2008: 219). This spirit of collectivity, pronounced early in Varda’s career, became the structuring watchwords of her final film, Varda par Agnès: ‘Inspiration, Création, Partage’ (2019). [5] She details each category in the film, and lest we forget, we have Varda seated on the beach in a director’s chair, facing the blue expanse of sea and sky with the inscription of the triad, imprinted on tee shirts, coffee mugs, coin purses, and totes. But the real importance here is the emphasis on ‘partage,’ sharing, for it is this dialectical process that makes Varda’s sense of self so different from the masculine solipsism of the New Wave guys. Again, Sellier is eloquent on this point: ‘With this declaration [on the importance of encounters], we can measure the ideological separation between Varda and the young Cahiers filmmakers. Instead of the claim, inherited from romanticism, of a tragic solitude that alone permits the construction of a self, Varda maintains that each person is constructed through the encounter with another’ (Sellier 2008: 219).

Nowhere is this sacred connectivity more evident than in one of the most important of Varda’s installations, ‘Les Justes au Panthéon’ (2007), about which she states, ‘Occasionally I got to work on the inside of history’ (Varda, Varda par Agnès [2019]). This is a modest comment for this installation, commissioned to accompany the dedication of a plaque in the Panthéon—the vast mausoleum in central Paris reserved for France’s illustrious figures who contributed to French history—honouring the thousands of ordinary people who hid, and therefore saved, Jews (mainly children) during World War II. It is inventive in its engagement of the viewer, in keeping with Varda’s ‘third life’ philosophy of finding new ways to immerse her viewers not only in her vision but in the possibility of inventing their own. As I note in my essay in the anthology The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda, ‘Les Justes au Panthéon is a breath-taking combination of historical recognition and minutely detailed, intensely personal fictive vignettes which inscribe a distinctive female voice and sensibility in this institutional hall celebrating great men’ (Flitterman-Lewis 2022: 83). On the floor of the immense space are photographs, like open books, of rescuers both named and anonymous, and some actors who portray them (Fig. 5). There is a large tree on a screen at one end of the hall and four filmed loops, two in black and white, two in colour. Varda points out that the black and white footage is shot from a distance, imitating the objective, impersonal stance of newsreels; the same episodes are shot in colour, focusing on details and intimate gestures. Varda explains that people can combine images from both screens and construct their own stories, a true culmination of Varda’s cinematic desire in three dimensions. In addition, when the installation is presented cinematically in The Beaches of Agnès, Varda prefaces it with a memory of her own adolescence during the War—checked pinafores and chants in praise of Maréchal Pétain. [6] She thus embeds the installation and her creative process within an account of personal memory. She disappears physically in order to turn her own memories into wider significance—historical and cultural memory. By manipulating temporalities and making the installation part of her own subjective and creative history, Varda invents a way to personalise the historical and to immortalise the ephemeral.

Fig. 5: Les Justes (Programme 15, Supplements: Installations #8 Hommage aux Justes 34:10-45:01).

And finally, we return to sunflowers. ‘The Greenhouse of Happiness’ is a deceptively simple title for an inventive installation that provokes so many different feelings and serves as a joyful culmination of an extraordinary career. This happily aging, energetic, ever-creative auteure welcomes viewer-participants into the world she has created and eagerly explains her process. She emphasises the Sunflower Shack’s importance not only because it is the most recent (we expected her to live forever) but because it best expresses her philosophy. Traditionally a ‘greenhouse’ is defined as an enclosed structure, most often of glass, used for the cultivation or protection of tender plants; Varda uses her celluloid greenhouse to cultivate new ideas and experiences, and to revisit past ones. Dominique Bluher provides a very thorough definition of ‘shacks’ in the context of this installation, and in so doing reveals what intrigues Varda most—the recycling and repurposing of elements of past works into new and unexpected creative structures. This in itself distinguishes Varda’s cabane work from other installations. Apart from her interest in marginal communities and ordinary folk, and her recycling of unexpected elements into aesthetic constructions, Varda has consistently provided a non-judgmental, non-condescending enthusiastic exploration of childhood. In later work her celebration of family abounds: ‘I’ve always loved having children around,’ she says, and ‘The kitchen is the heart of the home’ (Varda 2008). Imagine Spielberg or Scorsese making such a statement! And we can see this in the emphasis she places on the participation of her own children, Rosalie and Mathieu, in many of her films (Rosalie in One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, Mathieu in Documenteur and Kung-fu Master! for example). They have now become powerful agents of her legacy. And notably, the career-resuming The Beaches of Agnès contains the memorable sequence of the whole family dancing on the beach in flowing white attire while Agnès, the master of ceremonies, dances in black. Varda’s ‘Cinema Shack: The Greenhouse of Happiness’ re-enacts this love in the context of an art installation, once again bringing a feminine voice and concerns into the austere spaces of gallery exhibition. Varda exults in giving Le bonheur a second life, as nature and cinema are recombined in a playful interactive game. But, as is usual with Varda, there is a contemplative undertone. In Interview Magazine she describes her life’s process through the three phases of her career—as photographer, cineaste, and visual artist. In the spirit of the vitality and beauty of the sunflower she declares: ‘I’m curious. Period. I find everything interesting. Real life. Fake life. Objects. Flowers. Cats. But mostly people. If you keep your eyes open and your mind open, everything can be interesting. The secret is that there is no secret’ (Obrist 2018).

Acknowledgements:

In memory of my beloved colleague and friend Alan Williams, whose enthusiasm for and knowledge of French cinema fuelled my imagination for half a century.

*

This is a version of a keynote lecture presented at ‘Reframing Varda’ (1-2 September 2022, Humanities Research Centre, University of York, convened by Prof Erica Sheen and Dr Nicole Fayard). I wish to thank the organisers, the participants, and an array of colleagues and friends who sustained me, cheered me, and brought me sunflowers: Sharon Flitterman-King, Nadine Boljkovac, Colleen Kennedy-Karpat, and Joel Lewis.

Notes:

[1] Bluher says, ‘It is extremely difficult to find an English equivalent for cabane. In French, cabane relates to several simple kinds of small constructions crudely built of natural, found, or salvaged materials. Although it refers to shacks, sheds, huts, or cabins built for adults’ shelter, storage, or leisure, the term is also very closely associated with special self-constructed children’s places such as secret hideaways, forts, or treehouses’ (Bluher 2022: 195-96).

[2] This and subsequent translations are mine.

[3] Lieux de mémoire, or sites or memory, are historical and cultural artefacts that embody the memorial heritage of a given community (Nora 1997).

[4] Original spelling reproduced.

[5] Varda par Agnès was originally conceived as a two-part television mini-series and later released as a feature film.

[6] French viewers especially would appreciate the paradox inherent in juxtaposing images of Pétain’s collaborationist government with those of the sacrifice of the Justes.

REFERENCES

Armes, Roy (1966), French Cinema Since 1946, Vol. 2: The Personal Style, London: A. Zwemmer/ A.S.Barnes.

Aragon, Louis (1944), Le Crève-Coeur et Les Yeux d’Elsa, Londres: La France Libre.

Aragon, Louis (1967 [1956]), Le Roman inachevé, Paris: Gallimard.

Bluher, Dominique (2022), Notes to Exhibition ‘The Third Life of Agnès Varda,’ Silent Green, 9 June-20 July 2022.

Bluher, Dominique (2021), ‘Varda’s Third Life,’ Camera Obscura 106: Future Varda, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp.195-6.

Conway, Kelley (2008), ‘Varda’s Unique Approach to Self-Representation in The Beaches of Agnès,’ No. 15, The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (2020).

Conway, Kelley (2015), Agnès Varda. Baltimore: University of Illinois Press.

Conway, Kelley (2020), ‘Varda’s Unique Approach to Self-Portraiture,’ No. 15, The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (2020).

Flitterman-Lewis, Sandy (1996), To Desire Differently: Feminism and the French Cinema, New York, Columbia University Press.

Flitterman-Lewis, Sandy (2022), ‘Passion Commitment Compassion: Les Justes Au Panthéon by Agnès Varda’, in Colleeen Kennedy-Karpat, and Feride Cicekoglu (eds), The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda: Feminist Practice and Pedagogy, London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 83-97.

Koresky, Michael, ‘Notes to The Beaches of Agnès (2008)’, No. 15, The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (2020).

Nora, Pierre (1997), Les Lieux De Mémoire, Vol. 1: La République La Nation, Paris: Gallimard.

Obrist, Hans-Ulrich (2018), ‘The Life and Times of International Treasure Agnès Varda’, Interview Magazine, 5 September 2018, https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/the-life-and-times-of-international-treasure-agnes-varda (last accessed 15 May 2023).

Sellier, Geneviève and Kristin Ross (2008), Masculine Singular: French New Wave Cinema, Durham: Duke University Press.

Vancheri, Luc (2010), ‘Les Cabanes d’Agnès Varda: de “l’échec” au “cinéma”’, July 2010, Paris, France, pp. 121-132 ⟨halshs-00597943⟩ (last accessed 1 June 2023).

Varda, Agnès (1975), ‘Propos sur le cinéma recueillis par Mireille Amiel’, Cinéma 75, No. 204, December 1975, pp. 38-55.

Varda, Agnès (1998), ‘Agnès Varda on Le bonheur’, The Criterion Channel, https://www.criterionchannel.com/le-bonheur/videos/agnes-varda-on-le-bonheur (last accessed June 12, 2023)

Varda, Agnès, Chris Darke, Adrian Martin, Amy Taubin Ginette, Vincendeau and Criterion Collection (2007), 4 By Agnès Varda, Irvington N.Y: Criterion Collection, n.p.

Varda, Agnès (2008), Sleeve notes on The Beaches of Agnès (2008), The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (2020).

Varda, Agnès (2019), ‘Agnès Varda « Trois pièces sur cour : la serre du bonheur, à deux mains et l’arbre de Nini”’, Domaine De Chaumont-Sur-Loire, Agnès Varda | Domaine de Chaumont-sur-Loire (domaine-chaumont.fr) (last accessed 12 June 2023).

Varda, Agnès (2019-2020), Gallery Exhibition, Walter Reade Theatre, Frieda and Roy Furman Gallery, Lincoln Center, New York City, 20 December 20-6 January.

Woolf, Leonard (ed) (1965), Virginia Woolf, A Writer’s Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf, London: The Hogarth Press.

Films

4 by Agnès Varda (2007), dir. Agnès Varda.

Agnès de ci de là Varda (Agnès Varda: From Here to There) (2011), dir. Agnès Varda.

Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1961), dir. Agnès Varda.

Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda.

Elsa la rose (1965), dir. Agnès Varda.

Jacquot de Nantes (1990), dir. Agnès Varda.

Jane B. par Agnès V. (Jane B. by Agnès V.) (1987), dir. Agnès Varda.

L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t) (1976), dir. Agnès Varda.

La Pointe Courte (1955), dir. Agnès Varda.

Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965), dir. Agnès Varda.

Le petit amour (Kung-fu Master!) (1987), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les créatures (The Creatures) (1965), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008)

Les veuves de Noirmoutier (The widows of Noirmoutier) (2006), dir. Agnès Varda.

Mur murs (1980), dir. Agnès Varda.

Oncle Yanco (Uncle Yanco) (1967), dir. Agnès Varda.

Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), dir. Agnès Varda.

The Complete Films of Agnès Varda (2020), dir. Agnès Varda.

Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), dir. Agnès Varda.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey