‘Shaping a Space of Understanding’: Marilyn Stafford’s Street Photographs of Cité Lesage-Bullourde

by: Julia Winckler , June 25, 2022

by: Julia Winckler , June 25, 2022

Introduction [1]

I want to consider the legacy of a small, but important set of historical photographs of children, taken in the post-war period by the American-British photographer Marilyn Stafford (b.1925) in the narrow streets of the Cité Lesage-Bullourde neighbourhood, situated not far from the Place de la Bastille in Paris. [2] In 1961, less than a decade after Stafford’s chance visit, the Cité was completely demolished, and all the residents were dispersed to new high-rise buildings on the outskirts of Paris. [3]

These photographs are relevant to contemporary audiences for a number of reasons, and below, I locate and consider their significance through the lens of histoire croisée methodology, developed as a relational practice by Michael Werner and Bénédicte Zimmermann (2004, 2006). This method provides a conceptual framework, as it is concerned with understanding cultural histories and experiences through acts of framing that ‘shape a space of understanding’ (2004: 39). Source material including photographs and written documents are explored through visual analysis, archival research, and reflective practice in order to investigate inter-crossing viewpoints (regards croisées, a sub-category of histoire croisée). By combining past and present perspectives and exploring overlapping histories and temporalities, archival material is enriched, and a multiplicity of perspectives can be brought to bear on questions of place, experience and time. One consequence of using histoire croisée to frame research is that it acknowledges plurality, intersection, and convergence in active, dynamic ways. Relationships and interactions, for example between macro and micro histories, can be investigated through one another. This process evokes and works with the past in order to create new meanings and insights in the present.

Mobilising & Reactivating Stafford’s Cité Lesage Images

This essay mobilises and reactivates Marilyn Stafford’s Cité Lesage- Bullourde photographs from several perspectives. I discuss some of the social and historical dimensions of the photographs, as I revisit both the time they were made and the time they were reintroduced into the public sphere. I consider the history of the area alongside Stafford’s own experiences as a photographer, and describe what she herself recalls about her day spent in the Cité photographing the children. I track the story of the negatives, most of which were lost many years later, and tell the story of the rediscovery of the few remaining contact sheets. [4] This archival material has a life of its own and reveals Stafford’s working practices and editorial choices. On the contact sheets, sections have been marked up with a Chinagraph pencil; some contact images were cut out and are now lost. others have been stapled together. The surviving material has the patina of time and the photographer’s interventions embedded within it.

These visual documents have been reactivated through curation of several exhibitions in various contexts starting in 2017, consequently making them accessible to contemporary viewers who can gain insights into the difficult living conditions and physical infrastructure of the Cité. I discuss the photographs’ reception and describe some of the moving and powerful audience responses, including from former Cité residents Alain Dupont and Françoise Friedlander, who each got in touch via social media to share childhood memories after seeing Stafford’s photographs online. I have also been corresponding with urban scholars, including Isabelle Backouche, who has recently tracked public and administrative narratives that resulted in the large-scale post-war redevelopment of various Parisian districts, and with Jean-François Théry, who in the late 1950s conducted the only known study about the Cité Lesage-Boullourde. Noting that the neighbourhood was soon going to disappear, and that measures to relocate the inhabitants had already begun, Théry was concerned by how this would affect the residents, and in 1958, he asked, ‘[w]hat repercussions will the disappearance of the Cité have on its current population?’ (1959: 234, JW translation).

Very few known images of the Cité exist; this was a poor, small and little-photographed neighbourhood. Therefore, Stafford’s photographs are even more valuable, and—to borrow a term coined by Pierre Nora (1980)— can now be seen to function as ‘lieux de mémoires’ (sites of memory) of the former Cité and some of its children. In this essay, I hope to show that Stafford’s photographs and their reactivation and renewed circulation in the public sphere each represent small, but important symbols of resistance to forgetting and erasure from collective and cultural memory. I learned about Stafford’s work while doing comparative research as part of a collaborative, interdisciplinary team that tracked the history of social reform visions in Canada and explored how the emerging disciplines of social work and photography interacted. In particular, we worked with archival photographs commissioned by urban planning and public health departments, as well as philanthropic organisations in the first half of the 20th century, when cities like Toronto and Montreal vastly expanded.[5] Most of the photographs we surveyed documented migrant and working class communities in centrally located neighbourhoods. But these photographs were frequently used as ‘evidence’ by city administrators in order to label these areas as ‘slums,’ and this in turn would lead to the demolition of many residential areas under the guise of so-called ‘slum clearance.’ Following demolition, the residents would usually be rehoused on urban peripheries, leading to their further marginalisation, while the urban centres of cities became gentrified or were turned into business or administrative districts. This process started as early as the 1910s and continued up until the 1970s.

Our project challenged the labelling of these areas as ‘slums’ and we were critical of the lingering class prejudice that is palpable in the naming of children as ‘street urchins’ in historical, but also recent, writing on archival photographs of youngsters who lived in poverty. By investigating the histories of some of these lost neighbourhoods, census documents, oral history records, and also carefully scrutinising archival photographs and original glass plates and negatives, we could see that the streets and alleyways had also been an important terrain of communal activities, including small industry and informal economies, as well as a playground for children. Children at work or at play featured prominently in many of these photographs, but they would frequently only be recorded on the margins of those taken for site mapping purposes. Elizabeth Edwards uses the term ‘stowaways’—borrowed from Eelco Runia—for this kind of happenstance photograph (Edwards: 2014), where a subject’s presence in a photograph is unintentional. [6] Our project sought to put the children centre-stage. I also looked at parallel equivalences in the UK and France, probing the conditions under which these photographs were first made, and establishing the time of their rediscovery and recirculation in the public sphere. Frequently, this was more than half a century later.

I first met Marilyn Stafford (née Gerson), in late 2014 at an annual arts and literature festival in her hometown of Shoreham by Sea, near Brighton, where she gave a talk about her life. One of her photographs taken in Paris in the early 1950s shows a group of young boys helping each other onto a wall; just to their right, the steadying hands of an adult on standby come into view. I appreciated that this photograph was about the children: Stafford had portrayed them as independent protagonists. When I asked if she had taken any more street photographs of children in Paris, Stafford invited me to her home and showed me part of her photographic archive, much of which was still stored, at the time, in various boxes.

In recorded conversations that began in early 2015, and while sitting together in her home, Marilyn Stafford generously shared her passion for social justice and documentary photography (Fig. 1). [7] I learned that her photographic career had spanned three continents and lasted five decades, and that her commercial work included street photography, architecture, fashion photography, and portraiture. Originally from Cleveland, Ohio, Stafford moved to New York and then to Paris, Rome, Beirut and eventually London. Alongside her commercial work, however, she was always drawn to making documentary images. Early on in her career, while living in Paris, she started to take models wearing prêt-à-porter fashion out into the streets, in doing becoming one of the first photographers to merge street and fashion photography in the guise of an urban flâneur. She recalls that, ‘bringing the life of the streets into it was part of who I was.’

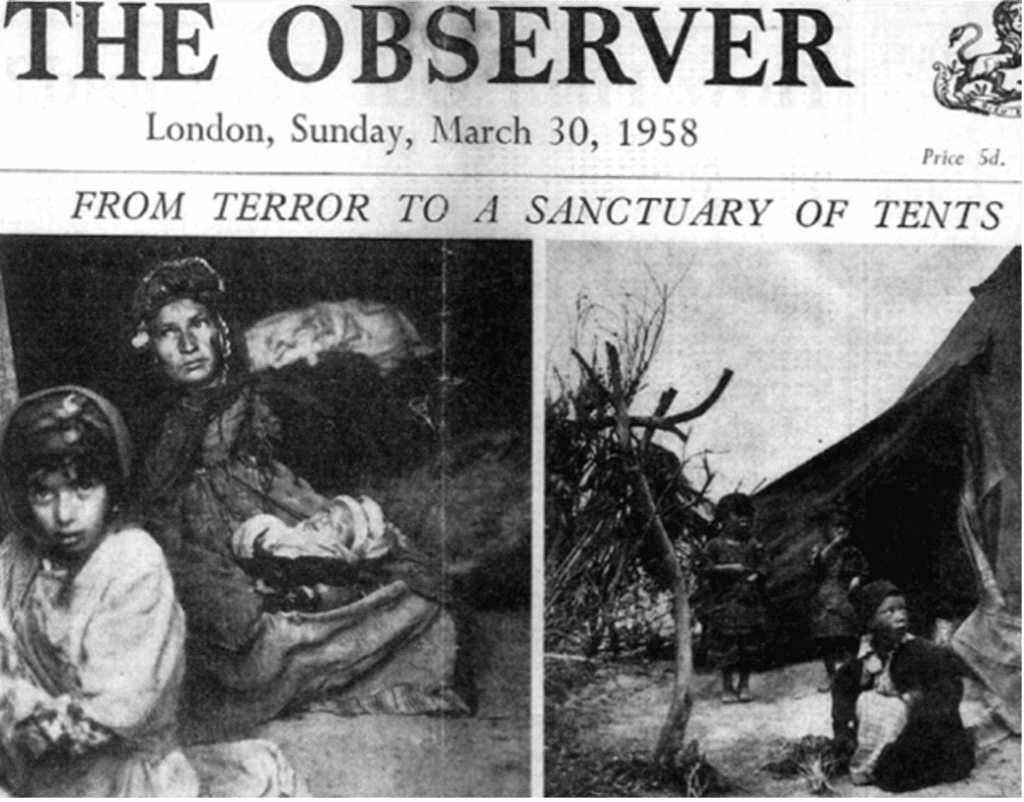

She frequently focused on social justice issues, hoping that her photographs would generate empathy and spur people to action. For example, in 1958, in the midst of the Algerian War of Independence, Stafford documented the plight of Algerian refugee families who had sought sanctuary just across the border in Tunisia in a makeshift camp. This included photographs of mothers comforting their small children, and of young children on their own in small groups. The Observer newspaper in London used two of Stafford’s photographs on its front page in late March 1958 (Fig. 2).

This was the first (but not the last) time that Stafford’s photographs would be used on the cover of a national newspaper. In the 1980s, just before retiring from working as a photographer, Stafford covered a story on the plight of sexual violence against women in India, which was published and raised funds to support a local women’s refuge. Showing compassion and solidarity and inspiring action has been a central tenet of her work and in 2017, she launched the annual Marilyn Stafford Fotoreportage Award for Women. [8] This has already become an important photographic award for women photographers performing socially engaged, political work.

Stafford explains that her deep affinity for migrants, displaced people and communities living on the margins of society stretches back to childhood, and growing up during the Depression, where she witnessed people being forced out of their homes. Although she moved to New York to become an actress, she was encouraged by a friend at the Screen Actors Guild to take up photography and was given a Rolleiflex camera. She gained some early experience with Fashion photographer Francesco Scavulla as his darkroom and studio assistant. At the age of 23, in December 1948, Stafford accompanied a friend to Paris. She recounts that she ‘instantly fell in love with France,’ and realised that she wanted to spend more time there, and so she returned in 1949. In 1951, whilst performing as a singer at Chez Carrère, she met Edith Piaf, and also became friends with Robert Capa, whose photographs of the Spanish Civil War had made the cover of many international magazines, and are now among the most iconic photographs of the Civil War. Being much younger than Capa, Stafford recalls that,

He was simply the most gorgeous person. He was like a big brother. I would go to him and ask him questions. Bob was open, he was Hungarian. I hadn’t any thought in my mind that I was good enough to take professional photojournalist photographs.

Encouraged by Capa, she took her Rolleiflex camera and ventured off by bus to discover the city and immerse herself in her new life. ‘I had two or three jobs in studios and studied with a studio photographer, but my feeling was to go out and find photographs.’

In doing so, Stafford joined an already-established tradition of urban street photography in Paris, which stretched back to Eugène Atget’s pioneering photographs of the city at the start of the 20th century, a time when it was undergoing large-scale transformation.[9] Atget’s documentation of traditional trades, neighbourhoods, and communities suffering economic hardship and destruction would influence Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and David Seymour (who co-founded the picture agency Magnum in 1947), as well as Willy Ronis, Robert Doisneau, Gisèle Freund, and Brassai, who each took engaged documentary photographs, portraying night work, demonstrations, widespread unemployment, poverty, poor housing conditions, and homelessness. André Kertész documented Parisian street life before emigrating to the US in 1936; Sabine Weiss recorded lives lived on the margins of mainstream society just over a decade later.

Stafford felt at ease, even though there were very few photographers—let alone women photographers— ‘wandering about the streets making photographs. It was not long after the end of the war and very few people had cameras.’ A photograph by Robert Doisneau called ‘Butterfly child, Aubervilliers, 1945,’ taken of a young girl carrying a heavy milk jug, strongly resemblances one of Stafford’s own early photographs of a girl holding a milk bottle. [10] Stafford understands that her picture may remind viewers of Doisneau’s photograph,

In a sense we have all seen the same event happening and it struck all of us. We are not unique—we are all seeing these slices of life which are around us, which need to be kept as part of a collective memory. This was part of the everyday life in Paris at the time. [11]

Unlike some of her contemporaries, Stafford never posed any documentary street scenes; instead, she tried to capture incidental moments that she witnessed spontaneously. Stafford was introduced to Cartier-Bresson by their mutual friend, the Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand, and she recalls that she would frequently accompany the established photographer on urban photography walks. Cartier-Bresson always tried to blend into the background, and Stafford would learn from him,

to wear something totally unobtrusive. He always wore a raincoat and a hat. I took the habit of understating whenever I went out to take photographs. It became a pattern in my life. Even though I later worked for years in the fashion industry, I always wore something very non-descript to not stand out.

The Area Around Place de la Bastille: Historical Context

Stafford vividly recalls the day she spent in the Cité Lesage-Bullourde in the early 1950s. She had taken a bus from the rive gauche to the rive droite, all the way to the end of the line near the Place de la Bastille, where she was drawn to the narrow streets near Rue Keller and Avenue Ledru-Rollin in the Quartier de la Roquette. She followed a sign pointing towards the Cité Lesage-Bullourde, and after walking through an alleyway that opened out into a small, enclosed neighbourhood she found herself in narrow streets that were full of children playing. [12]

Although Stafford did not know this at the time, the Bastille area had a strong and complex history of radicalism, suffering, and resistance. The barricades of the June 1848 uprising by French workers had been located right at the entrance to the nearby rue du Faubourg St. Antoine. The Cité Lesage-Bullourde was built, in part, with material from the demolition of the old Bastille St. Antoine fortress (see Le Monde, 30 January 1957). By the turn of the 20th century, the area had turned into ‘a vast network of streets and courtyards, of tired looking houses, of dilapidated and structurally unsafe dwellings, of alleyways and passages that were not easy to discern or navigate for outsiders’ (Winckler, 2013:290). Small tailor and carpentry shops, run by successive waves of immigrants from Italy and Poland, along with Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews had moved there at the turn of the 20th century, resulting in a dynamic and diverse neighbourhood with workshops and small factories interspersed with residential buildings. [13]

Prior to WWII, many refugees from Nazi persecution had moved to this area, as well as to the Marais district. During the German occupation of France, mass deportations of Jewish residents began in July 1942 from Paris, first to Drancy Internment Camp, then to Auschwitz (see Klarsfeld: 2001; 2006). [14] In a detailed study, the activist Serge Klarsfeld (2006) bears witness to some of the former Jewish residents of the Cité, who were deported and subsequently murdered at Auschwitz. At least 27 families with 58 children were deported from the Cité Lesage-Bullourde. [15]

In the only existing ethnographic study about life in the Cité, carried out during 1957-58 and preceding the demolition of all the residential housing, aforementioned urban sociologist Jean-François Théry paints a vivid picture of the area (1959: 187-240). [16] Based on conversations with magistrates, social workers, civil servants, and local residents, Théry observed that between 1945 and 1953, workmen and new families had taken over workshops and flats that had been left empty, following the large-scale deportations of Jewish families. As new residents moved in, the neighbourhood’s demographic changed (1959: 229); however, living conditions deteriorated further. The arrival of new migrant groups, primarily from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco led to even more crowded living conditions. Based on a study by the Préfecture de la Seine from 1953, referenced by Théry, 60% of family units had to share just one small room, which would usually also contain a tiny kitchen space (1959: 207). The same study revealed that of 199 units surveyed, only 11 had water, gas and electricity; 103 had gas and electricity (but no water) and 81 had only one element ‘of comfort;’ three units had none at all (1959: 208, 209). There were only 15 public toilets for all 534 residents, and one water source per 120 residents. [17]

Théry described that the Cité became ‘particularly lively’ in the evenings,

[w]hen taking a walk around 19 pm, one is immediately struck by the large number of children who occupy the streets, while laundry dries in the windows and homemakers circulate with large buckets of water that they have to take up several floors to their lodgings … From all the windows hang clothes, kitchen utensils, boxes. One gets a sense that inside these homes, every centimetre counts. (Théry 1959: 191, JW translation).

Children’s Creative Interactions

Marilyn Stafford’s photographs and recollections of the Cité mirror Théry’s observations,

what I found was lots of children in the streets; there were no playgrounds for them to go to; there were little groups of kids and few mothers around … the children were curious about me, friendly, open, and warm—they just gathered round. They did all their little tricks—some pictures just happened to be there on the spot, and in some of them they acted up little dramas. In one photo a little girl’s hands are cupped—perhaps because I had a Rolleiflex camera and held it like this, she was playing a game and pretended she held a camera, too. The Cité had some very lovely architecture but had disintegrated over the years. People were living in very crowded conditions.

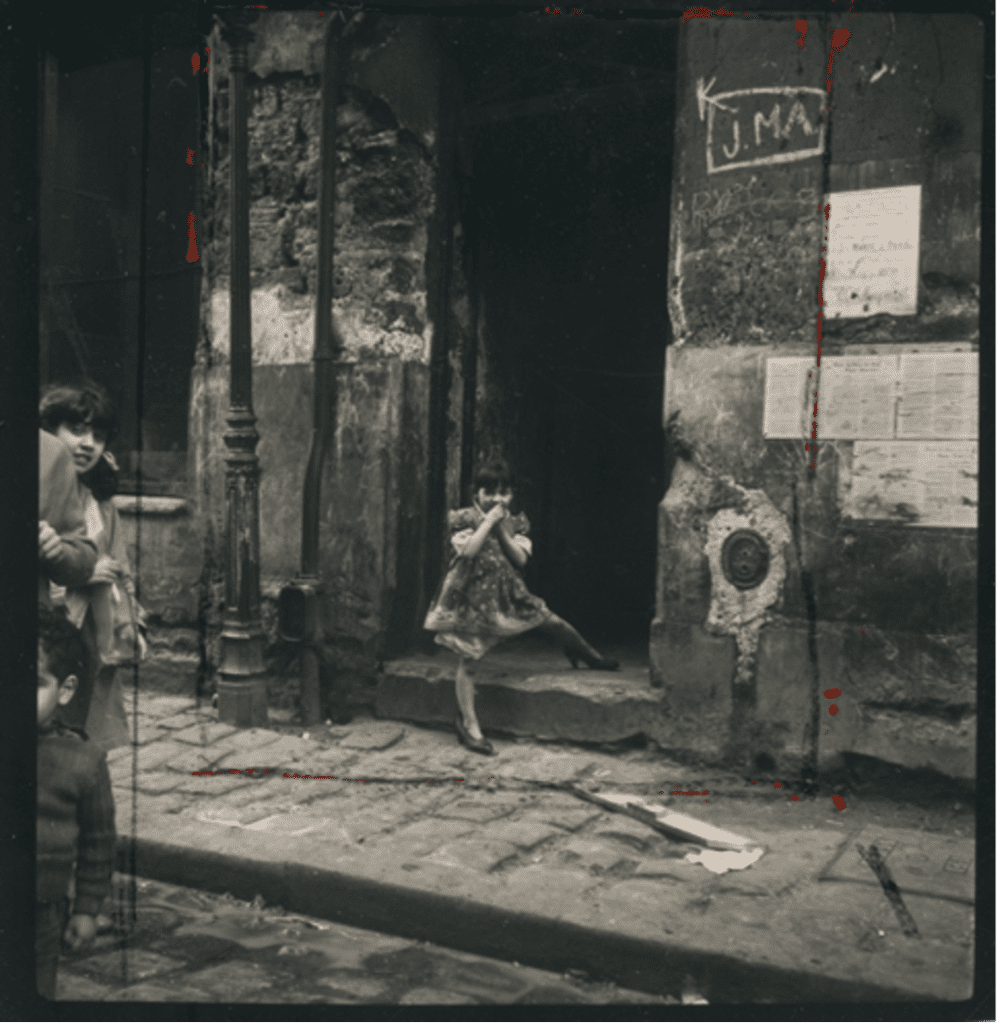

Stafford took several rolls of film, focusing on the children and their interactions. [18] Despite the harsh living conditions, Stafford remembers what she now describes as the energy of the children; her empathy with the children is palpable, as is the children’s playful movement in the narrow alleyways. Zooming closely into some of Stafford’s now-digitised contact sheets, it is possible to bring Théry’s and Stafford’s impressions back to life and to explore details (Fig. 3).

The central focus of this image is a young girl, who has been photographed standing in the entrance to a building. She wears oversized, high-heeled shoes and a dress with flower print. Her hands are folded together just below her chin, and she looks at the photographer a little tentatively. Just in view at the edge of the frame, is a group of three children, who are observing the photographer with curiosity. On a torn poster fragment the words ‘Pour la Paix en Algérie et pour l’Amitié’ are discernible, alongside chalk-drawn wall inscriptions. [19]

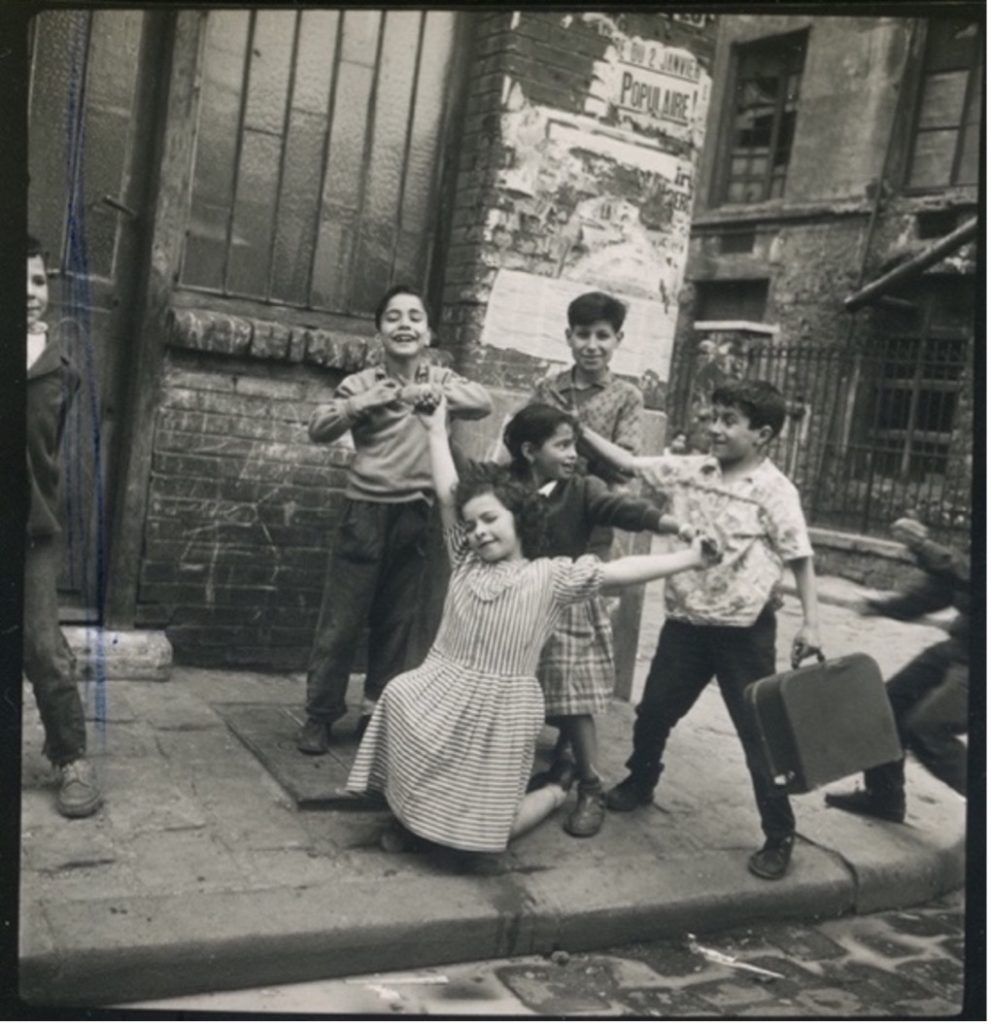

Another contact frame of a young girl wearing a short-sleeved dress with stripes running horizontally and vertically contains multiple storylines (Fig. 4). The stripes on the girl’s dress are in visual conversation with the lines of the brickwork behind her, with the pavement slabs, and even with the metal fencing of the saw-mill factory, Puzenat, situated just across the street.

There is hand-drawn graffiti, and torn poster fragments again refer to the crisis in Algeria. The children are standing on a central junction of the Cité, next to one of two small grocery shops. The girl kneels on the pavement as if taking a bow; her arms are stretched out, and she holds hands with a second, slightly younger girl, who stands behind her wearing a plaid skirt and dark top. Of the five children in the central group in this photograph, three are boys. They stand behind the two girls; everyone is either smiling or laughing. The boy in the light shirt is holding a small suitcase in one hand. With the other, he has made what looks like a V for victory sign but is possibly creating rabbit ears behind the head of the younger girl, who turns to see what he is doing. The suitcase adds to the intrigue of the photograph: why is the boy carrying a suitcase; what is inside? There is a lot of bravado—the street is the children’s playground—they have let Stafford into their game and allowed her to record their spontaneous street performance with her Rolleiflex camera. The photographer returns the affection of the children, and fashions a dynamic portrait, inspired by the growing canon of social documentary and humanist street photography. This photograph, like all the other photographs taken by Stafford in the Cité, captures moments in the children’s young lives, their future still lying ahead.

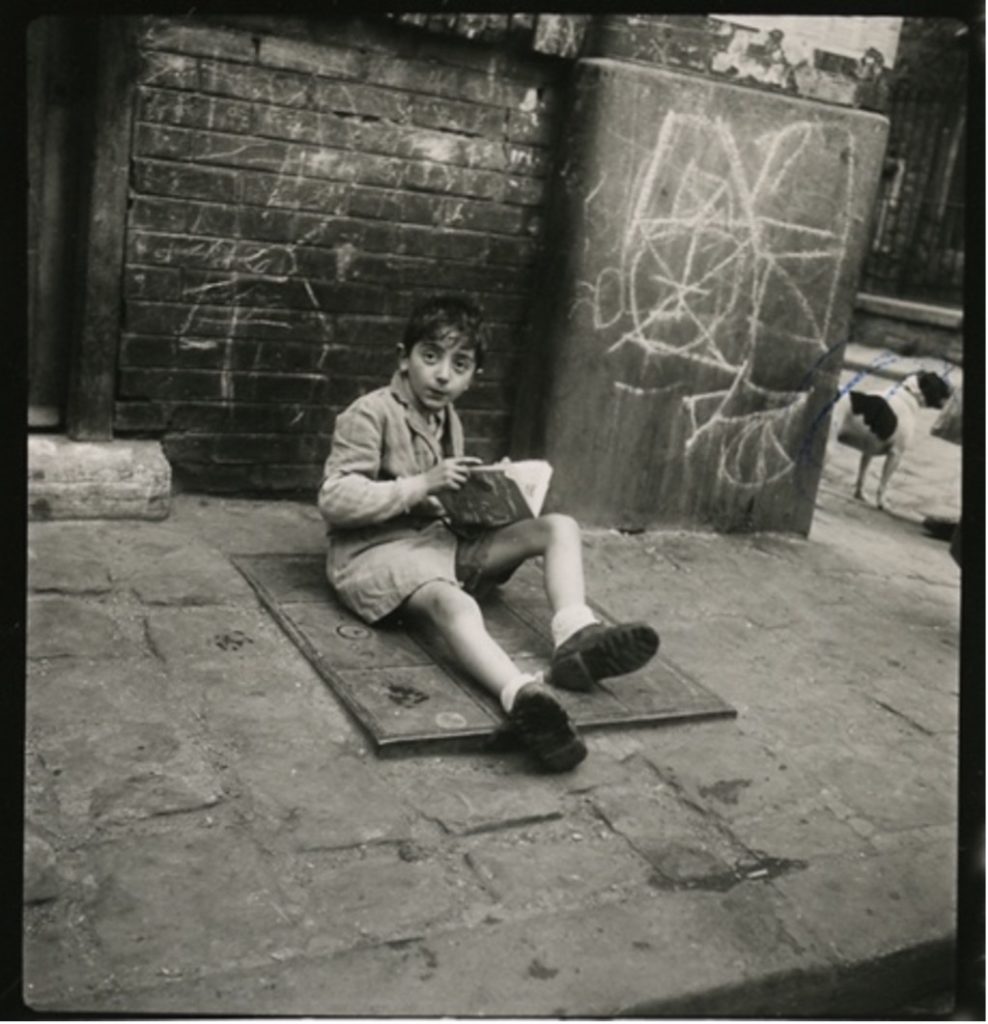

Children’s imaginative chalk drawings featured in some of Stafford’s photographs of the Cité; for example, in this image of a boy reading a comic novel (Fig. 5).

He is seated on a manhole cover at the main neighbourhood intersection, and his dignified posture and inquisitive curiosity towards the photographer defies the drabness of the surroundings. Framed by playful drawings of figures and shapes behind him, the boy has transfigured and transcended the immediate space around him, and has momentarily entered the word of his comic book.

Stafford’s images share an affinity with Helen Levitt’s work (1913-2009). Levitt began to make photographs of children playing and creating chalk drawings in the streets of New York in the 1930s (see Thomas 2018: 125). In her essay ‘Re-turning History,’ which explores Levitt’s street photographs in relation to the work of South African photographer Jansje Wissema, Kylie Thomas writes that,

[t]he photographs made by Levitt and Wissema provide a record of the social worlds the children they document inhabited; in this sense their works can be understood as intersecting with traditional forms of social documentary photography. At the same time the works of both photographers capture something of the way in which children refuse the “restraints that determine adult lives” (Elizabeth Gand 2011: 6) and, through creative play, transfigure the world they occupy. I read their photographs as a defence of forms of sociality that flourish outside of, and in spite of, the zones of administered life (Thomas 2018: 126).

Activating Photographic Archives as Dialogical Encounter: Regards Croisées

Stafford’s images remained suspended in time until the handful of surviving contact sheets resurfaced. At the invitation of the Alliance Française, Toronto, we created a small exhibition catalogue and had A0 poster size prints made from the contact sheets. This brought out all the details of the individual contact frames: for example, the children’s drawings and inscriptions on the outside walls of buildings. These enlarged contact prints, as well as 10 framed A3-size photographs from the series, were exhibited at the Pierre Leon gallery in Toronto throughout March 2017. [20]

We felt a strong sense of responsibility to pay tribute to the children and their families, and one way to honour their memory was to make extensive use of social media and Instagram as platforms to recirculate images online, in order to see if we could locate any of the children in the photographs or their descendants. L’Express, a leading Francophone newspaper, covered the exhibition under a title that underlined its significance—‘Pour que les enfants du Paris de l’après- guerre ne soient plus “invisibles”’ (‘So that the children of Paris after the war are no longer “invisible”’). A few months after the exhibition had finished, in August 2017, and responding to the appeal of the L’Express article, I was contacted via Instagram by a former resident, Alain Dupont. He wrote to say that he was born in the Cité in 1947 and had lived there until 1957, when his family was offered an apartment on a newly built housing estate on the outskirts of Paris. Dupont, who had lived in Batiment 3 for ten years, offered illuminating commentary. At first, his replies related directly to, and were inspired by, Stafford’s photographs. But soon, he became more involved in our project and started sending additional information, adding further context.

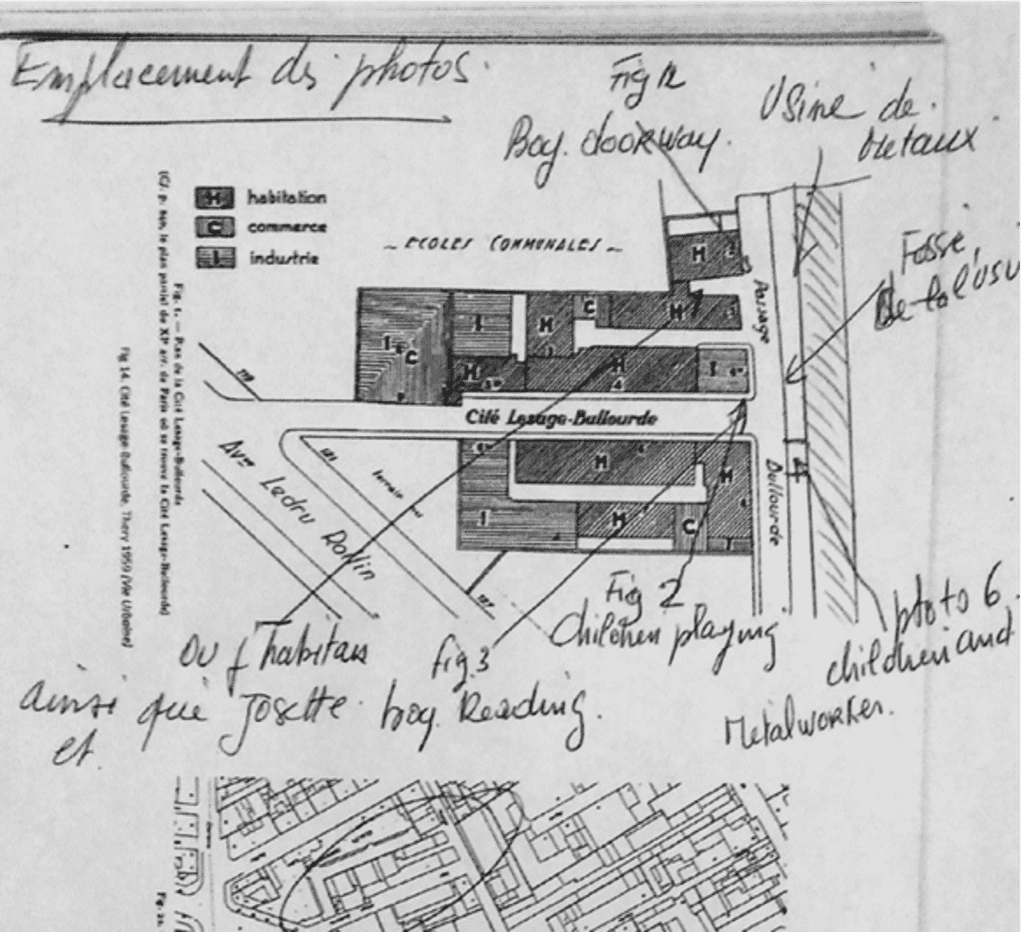

On the copy of a map originally produced by Jean-François Théry in his 1958 study, Dupont noted the exact locations where Stafford’s photographs had been taken in the Cité (Fig. 6).

For several months, we corresponded weekly, and as childhood memories flooded back, Alain Dupont sent story after story.[21] His account offers a personal and unique perspective of what life was like for residents who lived in the Cité around the time the photographs were taken. It begins with the arrival of his parents, who secured a tiny studio flat there in 1946. Below, I include just three short texts by Dupont, written in response to Marilyn Stafford’s photographs. These begin with Dupont’s parents’ arrival in the Cité,

After a difficult childhood, my father joined the army just before the start of WWII at the age of 19. He was made a prisoner and deported to Germany but managed to escape when Nazi Germany collapsed. He returned to Paris where he was reunited with his father and brother Paul who already lived in the Cité. Before meeting my mother, my father had moved into a 4×4 metre studio flat without running water at number 3, Cité Bullourde. I was born there in June 1947, during a summer heatwave, to my parents André, born in 1922 and Simone, born in 1924. They were two young people who had met a year earlier. At that point, my dad was working as a taxi driver, and my mother was a nurse. She agreed to move into this one room studio and adapted to it. The communal toilets on each floor were also the only source of running water for each flat. When my sister was born in 1955, our communal living space was reduced even more. [22]

Dupont also vividly writes about some of the neighbours who lived in adjacent flats. This short extract features some of the residents who lived in Batiment 3, none of whom we would have ever known about. Dupont movingly describes the solidarity and sense of community that existed in his building,

On our floor, our neighbours were Germaine and her son Gérard (he became an engineer); he slept on a pile of Mickey Mouse Journals that I had given him, and which served as a mattress. On the floor above us, (in fact it was the attic), lived a Chinese family and my mate Tchinguesse. Large families lived surrounded by the smell of roasts, and strange but pleasant cooking smells. Immediately next to us, and on her own, lived “Mère Solange” an old lady; at the end of the floor was “Père Joseph”, a Polish Jew who had survived the camps and who would later give his room to an Algerian family (right in the middle of the Algerian war). In 1954, many Jewish families from Algeria and Tunisia also arrived in the Cité; this included another friend, Tito. All of these residents intermingled without any problems, especially the children. We were happy, and had a normal life despite everything. [23]

In a last extract of his autobiographical narrative included here, Dupont describes the primary school on nearby Rue Keller. His account of the children’s resourcefulness in developing games and activities shines through:

We went to school between 8am and 6pm, and it wasn’t until when we left the classroom that the Cité belonged to us, but we didn’t roam around the whole neighbourhood, even though Marilyn Stafford’s photographs give the impression that children have been left out in the street. But it wasn’t like that, because there was no street lighting but for three or four gas lights, so on winter evenings all the children had to go straight home. In the summer we stayed out longer; our favourite place to hang out was by the sawmill at the end of the Passage towards Rue Ledru-Rollin. We made wooden swords, muskets, and sleighs with ball bearings as wheels, which annoyed the workmen. It is true that the pavements were our circuits—and watch out other pedestrians! [24]

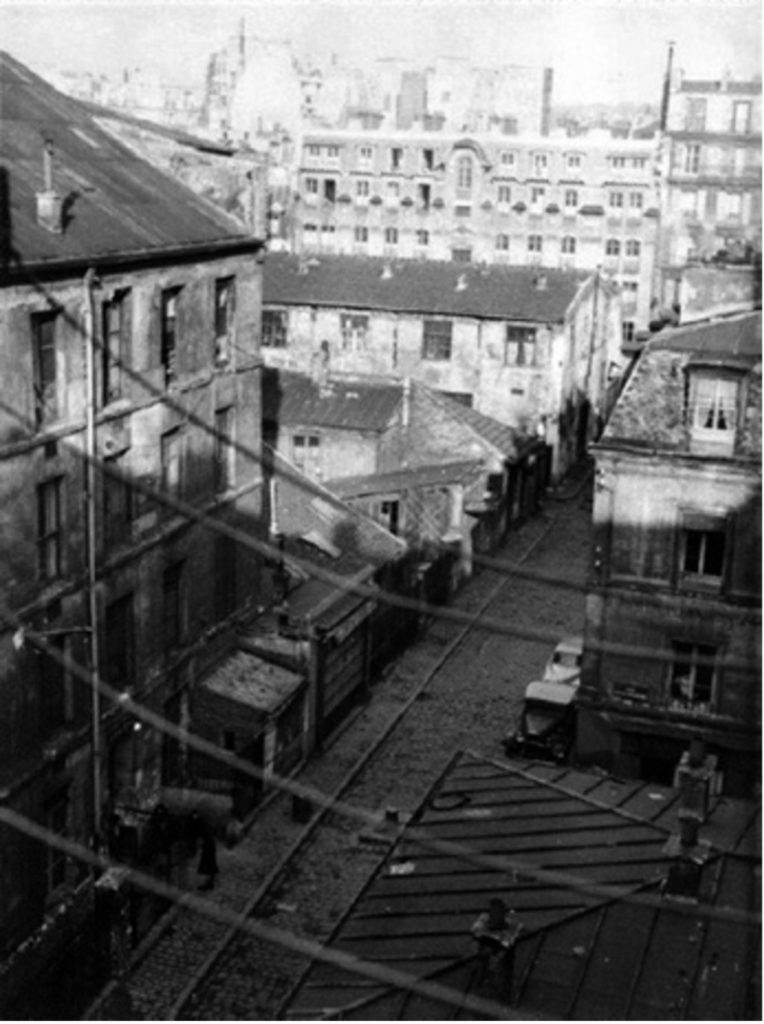

Alain Dupont also began to share some of his own family photographs, along with photographs a school friend of his, Josette Thomazeau had recently sent to him. The photograph included here (Fig. 7) was taken by Thomazeau’s aunt from the inside of her flat, and looks down at the passage below and the Puzenat sawmill factory, in front of which Stafford photographed many of the children.

This photograph, as well as those of Alain Dupont’s family (which included a picture of him as a toddler in a wooden crate outside his parents’ pallet business), are significant, as they offer new viewpoints and alternative representations of this neighbourhood. They extend the storyline of Marilyn Stafford’s photographs, help identify locations that feature in her images, and show other aspects of everyday life in the Cité. Most importantly, they—alongside Dupont’s expanding text—are now part of a growing collection of documents that help preserve the memory of the Cité.

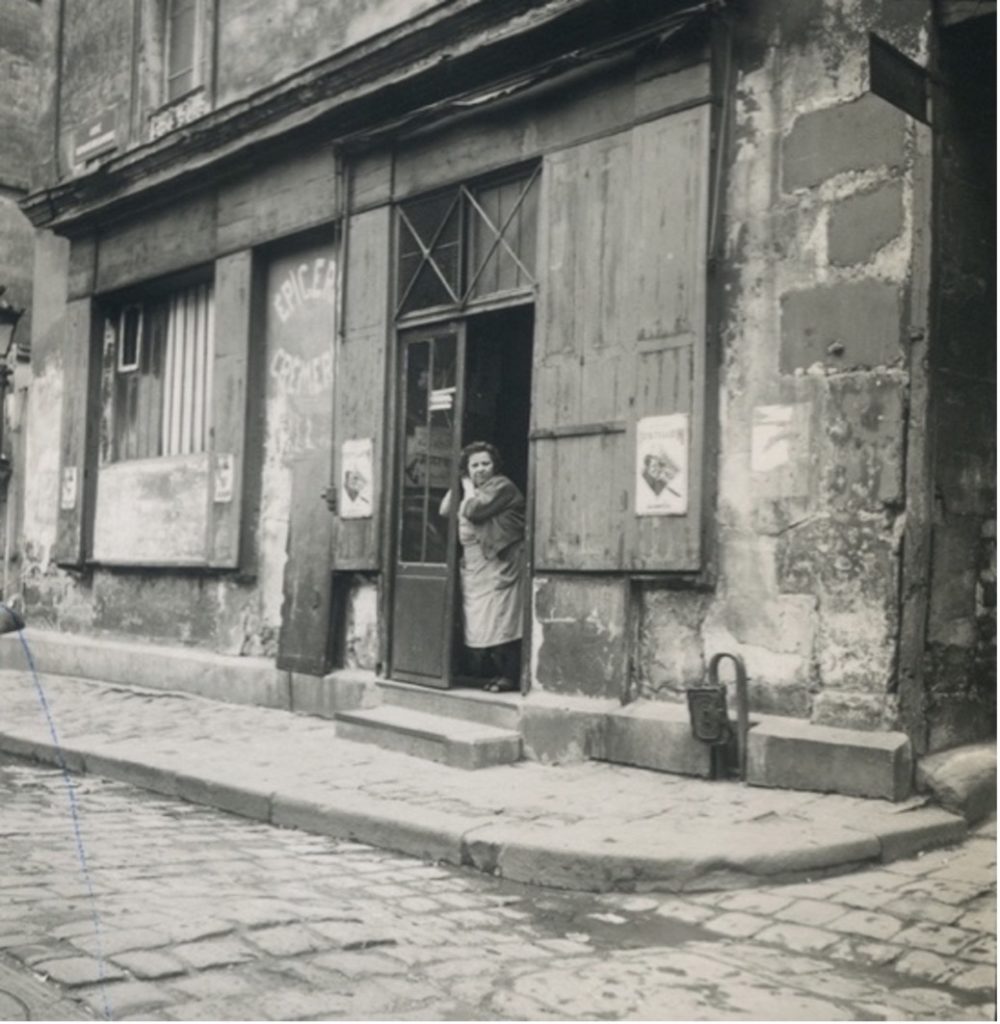

In 2018, we were contacted by another former resident, Françoise Friedlander, via social media. Friedlander was born in the Cité just one year before Dupont. In her emails, she wrote about the tragic loss of her father’s first wife Leah Rubinstein and their two daughters Germaine (17) and Rose (14), who were both arrested in the Cité and then deported to Drancy Internment Camp in 1943 together with their cousins, Fernande (21) and Marie (19) Rubinstein. [25] Françoise Friedlander’s brother Daniel, only three years old at the time, was saved by Mme Berthelet, a shopkeeper, who ran the only grocery shop located inside the Cité. Friedlander recalled that Mme Berthelet hid and protected her brother during the Nazi raid. After the war, Mme Berthelet continued to be very kind to Françoise Friedlander’s family and would often keep extra food for them.

In an extraordinary coincidence, Stafford photographed Mme Berthelet by chance during her visit to the Cité, without being aware either of her heroic wartime deeds, or her name (Fig. 8). [26]

Learning about the shopkeeper’s act of courage nearly seventy years after taking a photograph of her was a very moving experience for Marilyn Stafford. The stories that have been shared with us by these former residents have led to a further and unexpected deepening of the photographs’ storyline, and we can now identify some of the children and adults in Stafford’s photographs, and celebrate the bravery of Mme Berthelet.

Alternative Visions

Marilyn Stafford’s photographs continue to circulate, and in November 2020, I organised a photography study event with Patrice Roland from the Maison de la Recherche de l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle around this set of images, which were curated into an online exhibition interweaving Stafford’s Cité images with her and Alain Dupont’s stories. [27] Plans to return the photographs to Paris for the very first time since they were made near the Bastille seventy years ago—and to exhibit them at the Sorbonne—sadly had to be adjusted due to the pandemic. Instead, the online event brought Marilyn Stafford together with Alain Dupont and Jean-François Théry for the very first time. Friends, colleagues, and postgraduate students from across Europe and North America joined in the presentations and discussion. [28] Adrienne Chambon, who had developed the original research proposal for our Canadian project, and who had herself lived in Paris as a child in the 1950s, reflected on how all of the new emergent perspectives both complicated and enriched our original project. In her presentation, she highlighted that our approach of being attentive to context and multiplicity ‘defies simplification,’

when the photograph is examined through the gesture of the photographer, the children’s poses, their different temperaments: joy, complicity, thoughtfulness, decisiveness, apprehension, the children on their own, in groups or clusters, then each ‘scene’ is a whole world.

The world of the Cité was made palpable again in a short film put together by Ian Hockaday, with material provided by Alain Dupont, in which Dupont read out his story accompanied by photographs from his family archive. The correspondence between Dupont’s own voice, narrative, and family images in relation to Stafford’s photographs offered a deep personal connection. Responding to Dupont, Marilyn Stafford described feeling very moved to know that people have personal connections to the Cité. Their interchange compelled her to make a powerful comment on the role of photography,

I don’t think photography or photographs should just be dead items, a thing that one collects and sticks on the wall. I love the feeling that it has a relevance and a personal sense and for this reason I am just delighted that these children are coming back to life, for me, for them and for their families.

As part of the symposium, we also played a short video that I had recorded with Théry in 2019, in which I asked him to reflect on the legacy of his ground-breaking original study. Théry argued that in the case of the Cité, overcrowding had been one of the main problems; but another was the complete lack of maintenance or investment in any of the buildings and residential units. He explained that from the late 1950s, most social housing was moved outside of Paris to the outskirts; the fate of the Cité was not unique. While new housing constituted a real improvement in living standards at the time, some of the high-rise complexes generated new problems, such as social isolation or stigma. When asked what advice he would give to contemporary urban planners and councils, he advocated for urban renewal approaches on a case-by-case basis, and a careful consideration of whether existing infrastructures and neighbourhoods can be saved or modified. Théry acknowledged that there are in many cases continued effects on residents and descendants of displaced communities that have ongoing ramifications—articulated through a sense of having been pushed out to the margins of the city and loss of community.

Today, only the Passage Lesage endures as a reminder of the neighbourhood’s former existence, but it has been transformed beyond recognition. The small area now contains modern residential buildings and a large primary school near Rue Keller, where some of the original residential buildings once stood. Il était une fois l’école is a small museum that contains a reconstituted pre-WWII classroom with original wooden school desks and a blackboard. It is located within the school itself and is run by a team of volunteers, including Michelle Leprévost, who I also contacted as part of my research, but who could not attend the symposium, though has since shared some of the archival material with pupils at the school.

Using Stafford’s photographs as a point of departure, and combining a multiplicity of viewpoints (of a former resident, urban sociologist, academic researcher, audience participants, and the photographer herself), our understanding of the value of these documentary photographs was enriched and enlivened. These discussions validated the fact that photographs have relevance and can be mobilised as tools to help witness, support, or challenge perspectives.

Conclusion

This text has foregrounded the historical context and temporalities that can be explored through Stafford’s photographs of the Cité via Histoires Croisées methodology, and the account of the surviving contact sheets and their rediscovery and digitization many decades later, which led to their subsequent reactivation, circulation, and reception in the public sphere. These images have now been given a new life, which in turn has brought the opportunity for new audiences to engage with the work. In turn, Stafford’s photographs have invited the sharing and circulation of other kinds of images and evocations, starting with Alain Dupont’s family photographs and those of his former neighbour Josette Thomazeau, to the renewed circulation of historical maps and survey images and exchanges between Dupont and Jean-François Théry. The digital images shared between Dupont, Friedlander, Stafford and me have acted as aide-mémoire and offered evidence for family narratives to be retriggered, and for complex stories of diaspora and loss to resurface. Through this exchange of images and stories, opportunities to make and contribute to intergenerational memories have been numerous. Interactions and conversations around Stafford’s photographs have transformed how these are viewed and understood in the present: there is now a deeper emotional understanding of the community they represent, and of the physical destruction of the neighbourhood, and the subsequent dispersal of residents.

Prompted by Marilyn Stafford’s photographs, these new connections and evolving conversations between other researchers, former residents and the local school have enabled a reassessment of dominant historical narratives. In working with these photographs, I have sought to foreground underrepresented historical experiences, which are still largely absent from mainstream media, and to make connections to the present. The addition of different viewpoints, narrative perspectives and personal experiences continuously augments the photographs’ significance. Connecting with the original researcher, Jean-François Théry, and starting a correspondence with Isabelle Backouche, whose own work as an urban historian extends Théry’s research into the present, have helped gather important historical perspectives on how public and administrative narratives were used to designate the Cité as an ‘ilot insalubre’ (or ‘slum’), which was used to justify the neighbourhood’s demolition. By bringing in the perspectives of Dupont and Friedlander, this problematic labelling, which also affected how the residents were perceived, is resisted and rejected. By making space for community perspectives and re-presenting experiences of marginalisation in collaborative ways, narratives are repositioned and alternative visions and versions of the Cité and its residents shine through. Far from being an exercise in nostalgia, I consider the collaborative gathering and sharing of knowledge as a form of slow burn social and political activism, that continues to develop through dialogue and exchange.

Reflecting on their responsibility as film makers and storytellers, George Perec and Robert Bober ask pertinent questions about archival photography’s potential to make sense of—and recover—‘that which is banal, everyday, that which is ordinary, daily life’ (1979).

How to describe? How to tell, how to look, how to read these traces? How to begin to understand what hasn’t been shown, what hasn’t been photographed, what hasn’t been archived or stored. [29]

Stafford’s Cité Lesage-Bullourde images, made with curiosity and genuine interest, offer only partial, fragmentary glimpses of what life would have been like for some of the many children who lived there. But these photographs have resisted the combined forces of time and circumstance and remain poignant and powerful today. Taken at the very beginning of Marilyn Stafford’s career, they already exemplified her humanist, empathetic photographic vision. By returning these historical images to the public sphere, we seek to pay tribute to all of the Cité’s past inhabitants, and hope that the existence of the neighbourhood’s many children, including those without a photographic trace, is not erased from public memory, but becomes, and remains, visible once more.

Postscript:

The first retrospective exhibition of Marilyn Stafford’s work, A Life in Photography, curated by Nina Emett in collaboration with Marilyn’s daughter, Lina Clarke, opened at Brighton Museum on 22 February and ran until 8 May. This exhibition has now travelled to Dimbola Museum & Gallery, Isle of Wight, where it can be seen until 16 October 2022.

Notes:

[1] The quote in the title comes from Werner & Zimmermann (2004: 39).

[2] This essay extends a text written for the exhibition catalogue Les Enfants de la Cité Lesage Bullourde et Boulogne Billancourt, Paris, 1950s (2020), Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris.

[3] An article from 1961 in Le Monde announced the neighbourhood’s imminent erasure. The journalist noted that urban redevelopments and road widenings were taking place in the area that had contained the Cité Lesage-Bullourde (Louis-Léon de Dann, 29.12.1961). Over the next couple of decades, the whole area became gentrified; in 1984 the new Opéra Bastille was built just a couple of streets away.

[4] Most of the original negatives that Stafford took of the Cité Lesage-Bullourde were lost when a moving company mislaid some of her crates. Only four medium format negatives, three vintage prints, and eight contact sheets survive.

[5] This collaborative SSHRC project (2013-2017) included colleagues Adrienne Chambon (PI), Ernie Lightman, Bethany Good from the University of Toronto; Vid Ingelvics and Mary Anderson from Ryerson School of Image Arts and Julia Winckler, University of Brighton.

[6] Eelco Runia, “Presence,” History and Theory, Vol. 45, No. 1 (2006), pp. 1-29.

[7] All of the personal information and quotes were offered by Marilyn Stafford during recorded conversations between us (on these dates: 24.2.2015, 10.12.2015, 8.2.2016, 9.5.2016. 18.11.2016). For this text, I draw on the interview transcripts and the most recent conversation on the 21.2.2020, which was filmed by Ian Hockaday.

[8] The award is facilitated annually by the organisation FotoDocument and its director, Nina Emett.

[9] On Atget, also see the recent exhibition, Eugène Atget Voir Paris, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, June-September 2021.

[10] For a detailed appraisal of documentary street photography of Paris between 1900-1968, see Julian Stallabrass’s Paris Pictured (2002). This also features the work of Doisneau, whose work clearly had a subconscious influence on the young Marilyn Stafford.

[11] The image of a boy and balloon was another iconic motif mobilised by Stafford. Her own version of a boy playing with a balloon inside the Jardin des Tuileries calls to mind Le Ballon Rouge, a well-known French film made on location in the 20th arrondissement around Ménilmontant with non-actors, and released to huge acclaim in 1956. The plot focuses on a young boy who finds a red balloon and begins talking to this new imaginary friend. Made primarily with and for children, the film carries strong moral lessons as others try to steal or destroy the balloon; the boy is not even allowed to take it on the school bus. Marco Ianzagorta argues that the film’s consideration of ‘the brutal nature of the human condition,’ can be understood as a ‘means to provide social criticism to the complex social and political problems that plagued France during the postwar years. https://www.popmatters.com/the-red-balloon-le-ballon-rouge-2496144272.html (last accessed 28 May 2021). The theme of child and balloon had also been used during WWII, for example by emigré Fred Uhlman during interment, when the artist made a whole series based around his new-born daughter with balloon, connoting the possibility of freedom.

[12] The Cité Lesage was founded in 1864 by entrepreneur Mr. Lesage, and its name was changed to Lesage-Bullourde in 1877, to include the name of Mr. Lesage’s father- in- law. The family made their money through the yarn spinning industry (Théry, 1959: 192).

[13] Many neighbourhoods, including the 11ème, 19ème and 20ème arrondissements had offered cheap housing, and therefore became reception points for migrants; the continued lack of investment and deteriorating infrastructure, coupled with overpopulation, turned them into so-called îlots insalubres, which in turn led to the demolition of houses and streets, either by the city to create social housing, or more often, and as was the case with the Cité Lesage-Bullourde, the areas were gentrified. The writer Georges Perec described some of these interconnections in the film Le Belleville de Georges Perec (1976), emphasising the important connection between urban history, migration, urban destruction and renewal.

[14] During the ‘rafle du vélodrome d’hiver’ 12.884 Jewish residents, of whom 4051 were children, were taken to Auschwitz (see Klarsfeld, 2006). Jean Luc Pinol writes that, ‘almost 24 per cent of the Jewish children deported from Paris were arrested in the unsanitary areas on the right bank of the Seine … the 11th arrondissement—with many unsanitary areas— was the district with the most arrests. 1217 children lived there before deportation’ (Pinol 2018: 257).

[15] see Amejd, XIe (2013). At numbers 3, 4, 5 and 8, Cité Lesage Bullourde ’34 Jewish children were arrested’ (Pinol 2018: 254).

[16] Théry and I met up in Crozon-Morgat, France, 23.8.2019, to discuss his pioneering research. He told me that Louis Chevalier, the social historian, and author of Classes Laborieuses et Classes Dangereuses (1958) had been his thesis supervisor at the College de France. Focussing on working class lives in Paris, Chevalier’s work represented a much contested but ultimately successful methodological turn in how social research would be carried out in France from thereon, as Chevalier argued for an empirical approach to exploring urban developments. Chevalier, himself influenced by the work of Maurice Halbwachs (1950) on the importance of place in maintaining a sense of belonging, helped Théry understand that resident communities develop emotional connections to their neighbourhood and to each other. He invited resident associations and service providers to come and share practical knowledge with students in seminar style discussions and was critical of urban regeneration projects led from above that did not take into account the experiences of local residents. Chevalier developed these ideas further in L’Assassinat de Paris (1977).

[17] An ongoing problem with a persistent rat infestation appears to have also gotten worse (1959: 219).

[18] At the beginning of her career, Stafford rarely dated her contact sheets. Based on visual references contained in these photographs (i.e. promoting peace in Algeria, see further below) these images could have been made around 1954.

[19] ‘For Peace and friendship in Algeria’ (my translation). There had been uprisings in Algeria against French colonial rule since 1949. The poster helps date this particular image somewhat, as the French-Algerian war formally began in 1954; it could have also been an earlier peace plea, posted by one of the peace leagues in Paris. The Algerian War of Independence ended in 1962.

[20] The exhibition was called Photographic Memories—lost corners of Paris: the children of Cité Lesage-Bullourde and Boulogne-Billancourt 1949-1954 and ran for one month in March 2017. A more recent exhibition of the Cité images was co-organised at the invitation by Henri Scepi and with support from Patrice Roland and Ian Hockaday at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris in November 2020.

[21] Our correspondence began in August 2017, and continues to the present. Excerpts from Dupont’s recollections were first published in French in Dupont, 2020 and have been translated by the author for inclusion in this essay.

[22] Dupont, ‘Les enfants de la Cité’ (translated by J.W.) in Mémoires photographiques des coins perdus: Les Enfants de la Cité Lesage-Bullourde et Boulogne Billancourt, Paris, 1950’s 2020: 20-21.

[23] Dupont, p. 20-22.

[24] Dupont, p. 20-22 22.

[25] Personal communication with Françoise Friedlander, 2018, 2020; also see AMEJD XIe (2013: 33). 16-year-old twins Jeanne and Maurice Rubinstein were also arrested in the Cité with their parents that same day. Their older sister Ida was the only family member who was saved, as she had stayed over with another cousin (AMEJD XIE (2013: 33). Ida Rubinstein is the mother of Françoise’ cousin Thérèse Bourou-Rubinstein.

[26] The Pavillion de l’Arsenal also has some photographs taken in the cité in the 1940s and 1950s. Remarkably, these also include a photograph where Mme Berthelet can be seen just outside her shop with a group of children playing in the street. Isabelle Backouche has done some research on the images kept at the Pavillion d’Arsenal (see Backouche 2013, 2019).

[27] See http://www.univ-paris3.fr/regards-croises-autour-des-photographies-de-marilyn-stafford-608373.kjsp?RH=1236682598223. The full, two-hour recording is available at: https://vimeo.com/478238327/a4f595845a. Link to the online exhibition here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=821sVFkD7nQ (last accessed 14 June 2022)

[28] This had the welcome advantage that Stafford was able to participate on what was actually her 95th birthday.

[29] See Perec and Bober’s film Récits d’Ellis Island: histoires d’errance et d’espoir (1979) made using archival photographs showing European migrants, hoping for a better life in North America, arriving on in Ellis Island at the start of the 20th century.

REFERENCES

Association pour la Mémoire des Enfants Juifs Déportés (AMEJD XIe) (2018) Sur les traces des enfants juifs déportés du 11eme arrondissement de Paris, Mairie du 11ieme, Paris https:// amejd11e.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/livret_expo2018_ amejd11_lowdef.pdf (last accessed 25 February 2022).

Amejd, Xie (Association pour la Mémoire des Enfants Juifs Déportés) (2013), Fragments de parcours d’enfants deportés du 11ème arrondissement de Paris, livret https://amejd11e.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/2011_extrait- du- livre_fragments_dhistoires_lambeaux_de_mc3a9moire.pdf (Exhibition).

Amejd, XIe (2012), Fragments d’histoire(s): lambeaux de mémoire: enfants juifs déportés du XIe arrondissement de Paris (1942-1944), Paris.

Backouche, Isabelle (2013), Aménager la ville: Les centres urbains français entre conservation et rénovation (de 1943 à nos jours), Paris: Armand Colin.

Backouche, Isabelle (2019 [2016]), Paris transformé. Le Marais 1900- 1980: de l’îlot insalubre au secteur sauvegardé, Paris: Créaphis.

Brassai, (1987 [1933]), Paris de Nuit, Paris Musées, Paris Bober, Robert 1994 ‘En remontant la rue Vilin’ in Belleville, Belleville: Visages d’une planete, Françoise Meurier (ed), pp. 397-418, Paris: Creaphis.

Récits d’Ellis Island: histoires d’errance et d’espoir (1980), dir. Bober, Robert and George Perec.

Bober, Robert and Georges Perec (1980), Recits d’Ellis Island: histoires d’errance et d’espoir, editions P.O.L.

Chevalier, Louis (1984 [1958]), Classes Laborieuses et Classes Dangereuses, Paris: Hachette.

Chevalier, Louis (1977), L’Assassinat de Paris, Paris: Calmann-Levy.

Edwards, Elizabeth (2014) Magnum: One Archive, Three Views exhibition catalogue, De La Warr Pavilion, Brighton Photo Bienniale.

Halbwachs, Maurice (1950), La memoire collective, Paris: P.U.F.

Klarsfeld, Serge (2006), Les 11,400 enfants juifs déportés de France; Le Centre national d’information sur les enfants juifs déportés de France, Paris.

Hervouet, Q. (2017), ‘Exposition sur les coins perdus de Paris à l’alliance française!’, Le Metropolitain, 16 March 2017, https://lemetropolitain.com/exposition-sur-les-coins-perdus-de-paris-a-lalliance-francaise/ (last accessed 25 February 2022).

Les Fils et filles des déportés juifs de France: Le Centre national d’information sur les enfants juifs déportés de France, Paris.

Klarsfeld, Serge (2001), Vichy-Auschwitz. La Solution finale de la question juive en France, Paris: Fayard.

Le Ballon Rouge (1956), dir. Lamorisse, Albert.

Mémoires photographiques des coins perdus: Les Enfants de la Cité Lesage- Bullourde et Boulogne-Billancourt, Paris 1949-1954. Virtual exhibition hosted by Maison de la Recherche – Sorbonne Nouvelle. Created November 2020. http://www.univ- paris3.fr/exposition-memoires-photographiques-des-coins-perdus–615866.kjsp

Mouch, Lila (2017), ‘Pour que les enfants du Paris de l’après-guerre ne soient plus «invisibles»’ L’Express, 13 March 2017, https://l-express.ca/pour-que-les-enfants-du-paris-de-lapres-guerre-ne-soient-plus-invisibles/ (last accessed 25 February 2022).

Pinol, Jean Luc (2018), ‘Geodetic Data and Spatial Geography: New Assets for Urban History’, pp. 250-270, in Ian Gregory, Don DeBats and Don Lafreniere (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Spatial History, London: Routledge.

Ronis, Willy (1996), A nous la vie! 1936-1958, Paris: Eds Hoebeke.

Stafford, Marilyn (2016 [2014]), Stories in Pictures, a photographic memoir, Shoreham: Shoreham WordFest Publications.

Stafford, Marilyn (2021), A life in Photography, Liverpool: Bluecoat Press.

Stallabrass, Julian (2002), Paris Pictured, London: Royal Academy of Arts.

Théry, Jean-François (1959), ‘Les habitants de la Cité Lesage- Bullourde à Paris’ Vie urbaine, July-September 1959, No. 3, pp. 187-240.

Thomas, Kylie (2018), ‘Re-turning History: Helen Levitt, Jansje Wissema, the Burning Museum Collective, and Photographs of Children in the Streets of New York and Cape Town’, Critical Arts, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 122-136.

Winckler, Julia & Marilyn Stafford (2020), Photographic Memories – Lost Corners of Paris: The children of Cité Lesage-Bullourde and Boulogne-Billancourt 1949-1954 | Mémoires photographiques des coins perdus: Les Enfants de la Cité Lesage-Bullourde et Boulogne Billancourt, Paris, 1950’s. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Sorbonne Nouvelle.

Winckler, Lutz (2013), ‘Willy Ronis – Place de la Bastille ‘absolument vide comme le mot, mais impressionante et memorable’ in Hanns-Werner Heister and Bernard Spies (eds.) Mimesis, Mimikry, Simulatio, Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag Berlin.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey