Sacred Cinema: An Interview with Luna Marán

by: Astrid Korporaal , October 5, 2023

by: Astrid Korporaal , October 5, 2023

Luna Marán is a producer, director, cinematographer, exhibitor, and cultural manager. Born and raised in the Indigenous Zapotec community of Guelatao de Juaréz, Oaxaca, she has worked for over a decade in out-of-school education, through the guiding principles of gender equality, diversity, and communality.

As co-founder of the Itinerant Audiovisual Camp (2012-2019), the JEQO (2019) self-managed space for feminist community cinema, and the Cine Too Lab seedbed for audiovisual projects, Marán has been active in questioning and shaping the role of cinema in the social and political life of communities. Her work in Guelatao has become an important national reference in Mexico for audiovisual training and exhibition. She also writes critically and poetically about the roles of women and art in her environment.

***

I spoke with Marán about the role of emancipation in her work, particularly in the way it connects to the Zapotec culture and their philosophy of ‘comunalidad.’ In her recent documentary Tio Yim / Uncle Yim (2019), she addresses the tensions between the role of her father, musician, philosopher, and activist Jaime Luna, within the community and her family. What does it mean to make a film as a family, and what is the relationship between intimacy and emancipation?

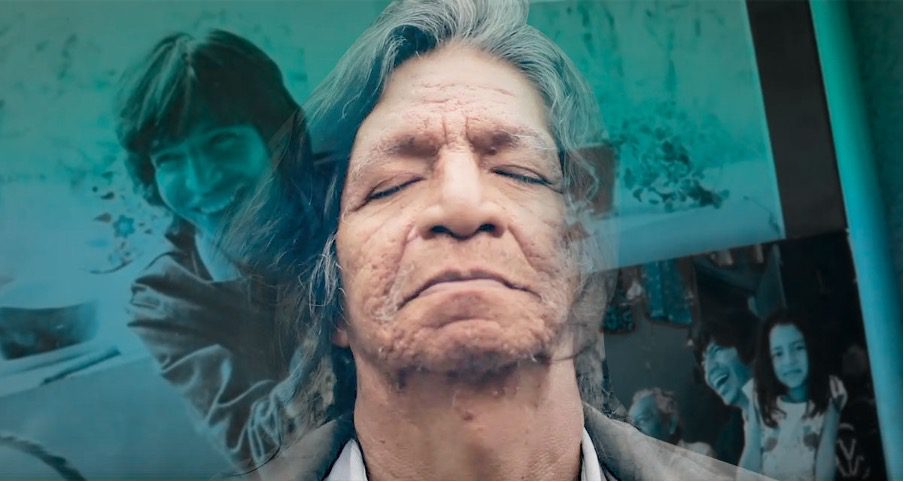

By including dialogues with her family members about the need and the use of the work in the film itself, Marán shows us how they negotiate the power dynamics and intimate truths of their shared reality. Marán’s father, mother, sister, and brother discuss whether this film might be a way for Jaime Luna to continue his storytelling after the loss of his singing voice through alcoholism. Marán’s brother questions why he needs to appear on camera, and her sister reflects on how they might discuss their father’s travels, work, and addiction without giving the impression that he was an absent or negligent father.

The presence of the camera in these conversations recalls a wider history of feminist filmmaking, for example Suzanne, Suzanne (1982) by Camille Billops and Joseph Hatch, or more recently Archana Phadke’s About Love (2019), where a daughter bringing her camera into a family dynamic challenges patriarchal assumptions of the passivity of this role. When done with care, as in Marán’s film and the examples above, a much more complex picture of familial relations and gender dynamics emerges, blurring the gendered and racialised associations with expressions of vulnerability or strength. Women play an important role in this film, especially Marán’s mother, who speaks about her own part in the establishment of an autonomous Zapotec radio station in Gelatao de Juaréz. She also reflects on the metamorphosis of love from her first infatuation with Marán’s father to her current care for him and their family. The film and its protagonists refuse to frame social and political activism as a subject of the past and younger, headier days, or as an interest which has been subsumed by domestic life. Rather than being cut off from social life by their domestic surroundings, Marán’s mother and father are both shown as surrounded by a family life that affirms and grounds their ties to a wider community.

Whether in scenes where the mother is folding plastic bags for re-use in the living room while listening to the community radio, where the father is sitting behind his laptop reciting the messages of support he has received via Facebook, or when the family attends a town meeting and festival, the viewer is presented with images of enduring emotions that feel more real than dramatised conflicts between generations, genders, or cultures. In a similar manner to Phadke’s film, which is set in Mumbai, Tio Jim refuses a wholesale colonialist rejection of the traditions and habits of older generations. Instead, the conversations we witness as viewers reflect a profound understanding of the ongoing legacies of colonial, patriarchal oppressions. It is these legacies that work through in the pressures and solitude that can lead to alcoholism and exhaustion, and which perpetuate the expectations of monogamy and heteronormativity that Marán also examines in her works.

The conversational mode, which is also used in one of her earlier films Me parezco tanto a ti / I look so much like you (2011), allows for a sense of trust and safety to be communicated, both with her interlocutor-protagonists and the viewer. This a counter-cinema of the real where the spectator is not assumed to be part of a system of social surveillance. In watching these films and the intimate, intergenerational dialogues at their heart, we can have the sensation that they are mainly intended for the community Marán is a part of. Yet we can also feel what it would mean to be part of a community where emancipation is a shared journey, and in which healing is always relational.

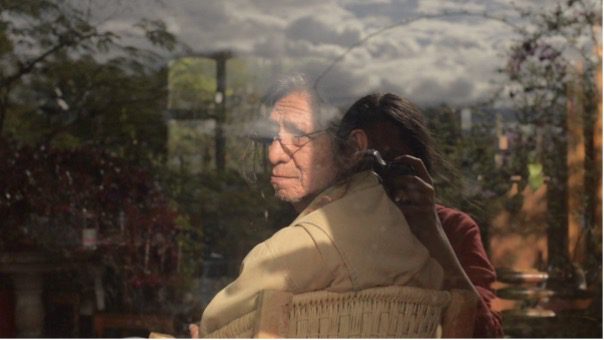

The recurring method Marán uses in Tio Yim of shooting through the windows of their home is not a way of creating distance between herself and her protagonists. Instead, the reflective surfaces include her in the conversation, while also signifying that the walls of this home are porous and supported by a sense of solidarity that resonates between the inside and the outside, the domestic and the public, the personal and political, as well as the human and the more-than human. Through her films as well as her work with the Cine Too Lab, Marán continues a genealogy of Indigenous filmmaking and media activism.

This genealogy is often associated with the re-appropriation of dominant modes of media production and dissemination. Even more important, perhaps, is the genealogy of feminist and decolonial filmmakers who have nurtured viewing and production possibilities accessible for their own communities, from the kitchen table to the cinema in the jungle. The communal way of life in Gelatao, which involves commitment preserving the land, is presented to us in the form of a microcosm where wider relations are never far away or closed off. Not shying away from complexities, the focus of the work of emancipation is not the spectacular exploitation of tensions, but the continuity of intentions.

***

Astrid Korporaal: In your article ‘Nuestro Proprio Espejo’ (Our Own Mirror), you write about the political importance of film for indigenous peoples in Mexico to see themselves represented on the screen. This representation is political, because it counteracts the erasure that takes place in mass media and gives community members self-esteem and pride in their own culture. Your most recent film, Tio Yím (2019), addresses difficult subjects such as alcoholism with a lot of respect and care. It seems to me that everyone involved in the film has committed to a radical honesty, even when they feel reluctant to be recorded on camera. This, I think, makes the representation that takes place in the film not only about visibility, but also about the opportunity to reflect on shared values. How do shared values play a role in your filmmaking?

Luna Marán: Yes, communality is a concept that encompasses the ways of living and being of Zapotec communities. This concept includes a way of seeing the world that puts the ‘sense of commonality’ at the center. For this, solidarity is necessary. Communality is a system of values, and solidarity is a value that is necessary for communality.

AK: You consciously connect the forms of community media established in your local town of Gelatao the Juárez to the legacy of your parents and grandparents, who fought to protect the rainforests in this area, and the larger Zapotec revolutionary movement. This has included an autonomous radio station, (XEGLO, La Voz de la Sierra), a television station (Canal 12 Nuestra Visión), and now also filmmaking and film workshops. How important have these outlets for expression been particularly for the women of the town, as media work is a community responsibility and run by assembly?

LM: I can’t speak for all the women in my town, but I can speak for myself, and for me they have been life changing. Growing up with content that reinforces cultural identity and pride in this identity has been very important. My work is a continuity, with some current reflections on the image, its forms of production and what might allow for the building community from the cinematographic practice. Reflections on subjects like feminism are things that our generation contributes to that continuity.

AK: You have spoken about Cine Too, the local cinema in Gelatao, and its importance as a space of joyful gathering for the community, a place of magic. How far can this sense of community extend, do you think?

LM: It is not easy for me to measure. but I think Cine Too is a project that serves as an inspiration in other territories and that continues to live a process of making itself exist every day. Cine Too is a theatre in a community of 500 people, it works with exhibition, production, and training as its axes. There are relationships with many projects, for example, we are part of the CEDECINE exhibition project network ‘Film Exhibition Community,’ and we collaborate with many others daily, inside and outside the community. As mentioned in ‘Nuestro Proprio Espejo,’ the word Too in Zapotec means magical or sacred, because for us the cinema, the movies, have that strange power, they can change our mood, our thoughts, and our deepest fantasies. We look at each other to know how we are, to imagine ourselves, to confront ourselves, to contain ourselves, to project ourselves into the future. This will be a continuous task that from generation to generation will allow us to continue making and producing material that allows us to look in the mirror, recognise ourselves, imagine ourselves and change ourselves according to our own critical processes.

Fig. 4: Luna Marán, Tio Yim (2019).

AK: You create your films in between other projects for the local community, such as documenting local festivals, events, and cultural activities. In Tío Yim and Me parezco tanto a ti (2011), conversations and learning between generations feel just as important as technical imagery or visual effects. How do you see the educational activities you are involved in as contributing to a different, revolutionary relationship between consuming images and creating action?

LM: I do not see these actions as separate; I believe that ‘to make a new image is to create a new world.’ For me, making an image is a political, in the same way intimate and personal relations are political. Cinema builds memory, for me it is a way of responding to my own interests, but also of reflecting collectively on a theme or issue. I would like people who see my films to be encouraged to make their own films or stories. It takes a lot of different points of view to understand the complexity that we inhabit.

More about Laura Marán:

Cine Too Cinema, https://cinetoo.org/ (last accessed 10 September 2023).

Marán, Luna (2020), ‘Nuestro Proprio Espejo’, Albora: Geografía de la Esperanza en México online, 17 May 2020, https://www.albora.mx/nuestro-propio-espejo/ (last accessed 10 September 2023).

Uncle Yim on Guidedoc, https://guidedoc.tv/documentary/uncle-yim-documentary-film/ (last accessed 10 September 2023).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey