‘Risky Images’: A Conversation with Phumzile Khanyile

by: Brian Michael Müller , June 25, 2022

by: Brian Michael Müller , June 25, 2022

Award-winning South African photographer and activist Phumzile Khanyile met Brian Müller to talk about her emerging career, the 2015 Gisele Wulfsohn Mentorship Program, and how instances of violence and childhood trauma continue to inform and shape her creative practice.

*

Brian Müller (BM): Let’s start at the beginning. Can you tell me about your early years?

Phumzile Khanyile (PK): I was born in Soweto in 1991. My childhood was up and down like any other. We moved around a lot, so I didn’t really have friends—there was definitely an element of isolation and I became extremely shy and withdrawn. I lost myself in story books. My fondest childhood memories were playing under our peach tree, but my worst would definitely be the fights that would happen at home. [1]

My dad was abusive towards my mom, and I would witness a lot of that mess. From my understanding they loved each other and there were good moments, however, it just never worked out. There was a lot of conflict at home so now and again we’d have to move to a safer space. Luckily, my mom found the courage to leave him. My family photograph album doesn’t have any pictures of him. Our album had more women in it—I could count the number of men who feature on one hand. Eventually, he went on to marry someone else.

I’ve been to a lot of schools: Dominican Convent, Malvern Primary… After primary school I wanted to go to an art school, but my mom had other ideas. I went to six different high schools in five years. I attended Christian Academy, then after a year of depression my mom conceded and enrolled me in Pro Arte Alphen Park, a boarding school. I was so naughty, and I got into a lot of trouble—I was in detention in my first week there. It was insane. I had a very traumatising experience there—I don’t really want to talk about it, but it’s something I’m still working through as part of my next photographic project—so the following year I went to Abbotts High School. My last year of school I home schooled, so there was no matric dance for me. If you had told me ten years ago where I’d be today, I wouldn’t have believed you.

Growing up it was just me, my sister, mom, and grandmother, so there wasn’t any male influence really, my brother came later in the game. Basically, I was raised by women. Family life was tricky because my mom and gran, Nomvo, would get into arguments and fights, however, there were also good moments—it’s just that the bad ones leave deeper scars.

My Childsplay series came about when I was photographing an editorial assignment while I was still studying at the Market Photo Workshop (MPW). I was beginning to stay true to my voice as a photographer. The work talks about how one can’t really run away from childhood scars. They’re something I still battle with today.

BM: Photography seems to be your principal method of confronting and processing these scars. How did you get into photography?

PK: To be honest, I never thought about photography, nor was I interested. Then, in 2013, I was going through a deep depression and my mom thought I needed to get out the house and do something. She told me about the MPW and so I went and started the foundation course. My mom and sister thought I took good images and wanted me to explore it further, so I did the intermediate course and eventually the Advanced Programme in Photography. To my surprise, it’s something that came naturally to me, and I had some great trainers who constantly pushed my limits.

I guess my love for creating images started a long time ago when I would lose myself in books. It’s one of the reasons I love reading—you get to create a whole movie in your mind. Growing up I was constantly in my own world; the family would joke around saying, ‘Oh she can’t hear us, she’s in her own world again.’ It was here in this imaginary world that I learnt to cope with and process what was happening to me and around me. Photography allowed me to share this world. So, photography itself wasn’t necessarily a coping method for me, but was a way of visualising the world where I learned to cope. I love that photography can transport people’s minds and emotions without saying a word.

In general, the way I look at photography is: ‘I can only tell you what I know and have experienced.’ It is very hard to not look back, because I find it is the only way to find yourself and what makes up your DNA and when looking at South Africa’s history a lot was disrupted for black families. For example, my surname isn’t really my surname, but because of the apartheid rules as a black person your surname had to correspond with the area you live in, and so I find looking back is part and parcel of moving forward, a lot of clues about who I truly am are in the past somewhere.

BM: In terms of ‘looking back,’ elsewhere you mention that you ‘have lost all of [your] family albums at home’ (Dee 2017) and, in some sense, are trying to (re)create them. Can you elaborate on this?

PK: My family albums were actually stolen which is so odd because who does that? The images that survived were the ‘bad’ photos that we kept in a box under the bed, and in these images there really isn’t any type of curation, the images themselves weren’t taken professionally, some have too much flash, some are double exposures, bad pictures we took of each other … The kind of stuff I like. [2] My family album would definitely look like the messy box images.

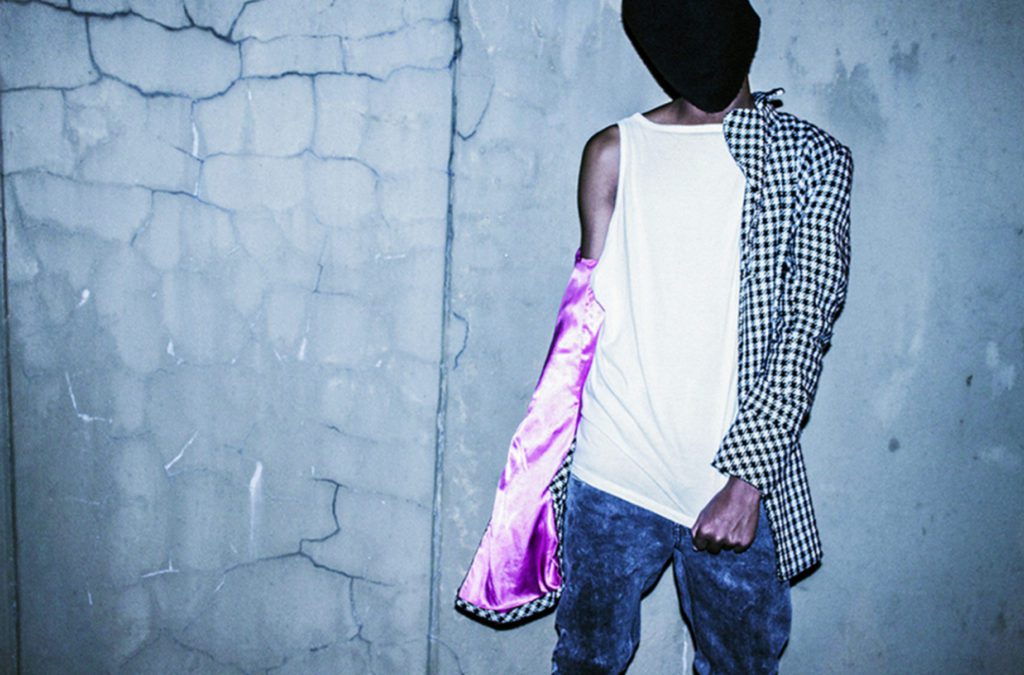

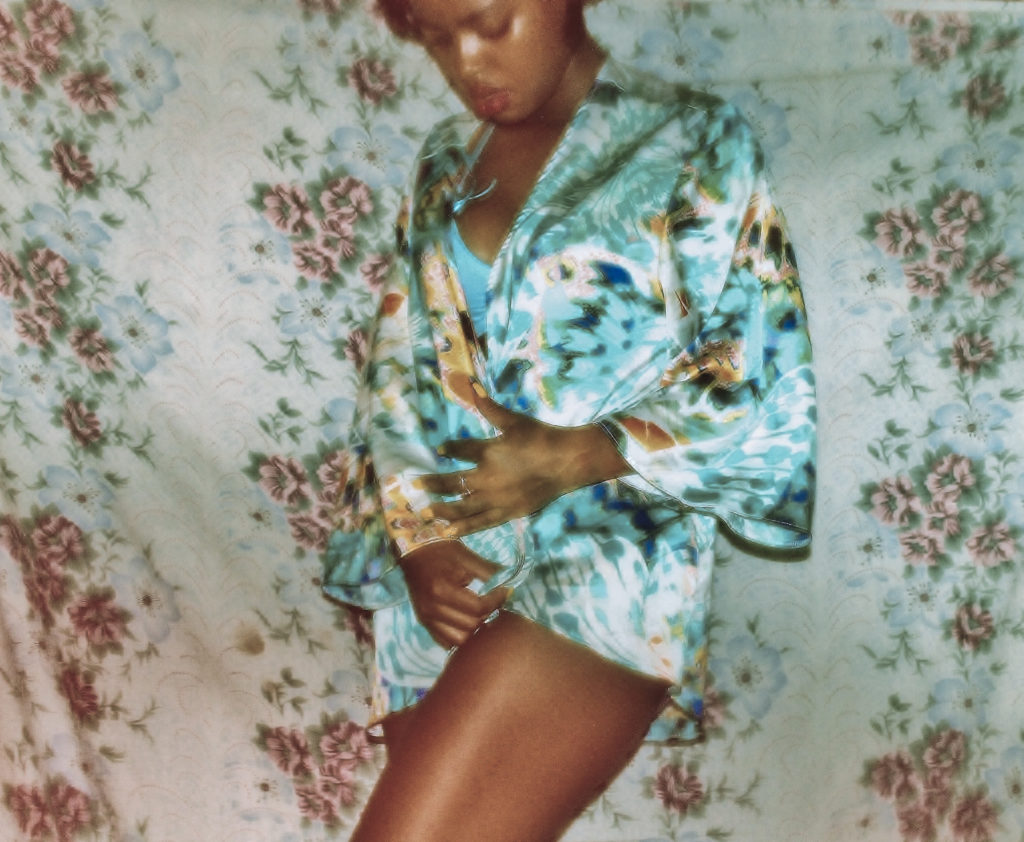

BM: And many do! I love your world-making praxis to get these ‘messy’ photographs: draping headscarves and chiffon dresses—these complex symbols of femininity and sexuality—over your digital camera to give your image the visual effect of old polaroids and prints made from imperfect negatives. [3] In thinking more about this process, I’m really interested in the clandestine nature of your production process. I have a wonderful mental image of you waiting for your grandmother to fall asleep or go to church so you could get out your camera, take pictures and then quickly pack everything up before she gets home and catches you.

PK: Yeah, I knew that my gran wouldn’t approve of my poses and dress code, so I would wait for her to leave or go to sleep and then I would go into her wardrobe to get stuff to wear. When she went to church, I knew I had about 3 hours to photograph and move stuff around the house, but when she was around I would wait for her to sleep and then I would photograph quickly and quietly. I didn’t want to be caught in her black heels and see-through lace nightie that’s for sure!

My grandmother’s understanding of photography is different to mine. She knows there are photographers who go around taking images of people and, of course, photographs in newspapers, but what I was doing was different to her understanding. Firstly, I was photographing myself and, secondly, I was switching personas. She doesn’t understand that photography can be conceptual. To her, it just looks like I’m taking risky images of myself with it happening in secret and all. I would put some of my images up in my bedroom—obviously the less risky ones—and she would sometimes come look at them.

My gran isn’t someone who shares her feelings easily. I heard she was excited to see me on the television; maybe getting recognised for my work is helping to change her perception of photography.

BM: Another article about you and your work notes that photographing indoors wasn’t your first choice but you were forced into it after being ‘attacked on the streets.’ (Almino 2017) Can you tell me a bit about this?

PK: Originally, I only wanted to photograph outdoors because my homelife was complicated and my gran didn’t understand what I was doing. Then one day I was attacked when I was walking home from MPW with a friend who lived a few doors down from me.

At the time, I was working on a school project that was inspired by the Where’s Wally? children’s books.[4] I would wear a striped dress similar to Wally’s striped outfit and photograph myself hiding outdoors or amongst crowds of people and the viewer would need to look for me in the photograph. One day when I was walking home from school—I had all my equipment with me—we stopped to shoot an image when we were attacked by five men with weapons. I don’t remember anything about them. I can’t tell you what they looked like or what they wore… I can’t really remember anything… I can tell you their heights but that’s really all I remember about them. They beat us up. I tried to run away but I couldn’t because I was in that dress; they caught me and hit me hard on the head. I have suffered from migraines ever since.

I told the attackers they could take everything, but I asked if I could keep the SD card in the camera and the hard drive which had all my originals. They didn’t care and took everything; I lost almost all my work. To recover some of the images I had to scan some small reference prints which just added to the aesthetic.

After that I started to photograph almost exclusively indoors. I hope to revisit the project again one day but not yet.

BM: I’m sorry that happened to you and you are suffering from migraines because of it—it’s a regular reminder of this traumatic incident. This element of violence definitely permeates throughout much of your work. One of the photographs that immediately comes to mind for me is the image of you straightening your hair with the clothing iron at home.

PK: That element in the work is really the true me coming out. It started to show around September 2014 when I began the Advanced Programme in Photography at the MPW, and began working on my 1411 Mohapi Street series. This is the only consistent place I have ever known. We would move somewhere and then have to move back to Mohapi Street, and so the cycle continued. It’s the only place I identify as home but I’ve always had a complicated relationship with this place. It was so weird that the place I most identified as home would also make me feel completely uncomfortable and out of place. I guess what made it home was the familiarity of it all, and how in this house different generations of woman fought to be heard and seen. That house has a lot of bad memories for me [and] this project is an attempt to work through what happened there. We lived under a lot of tension, we constantly had to tiptoe around because anything could spark an outburst of suppressed emotions. So there’s definitely a sense of a lot of who I was died while growing up in that house; however, it’s also the only place that I know as home. I definitely have a love-hate relationship with my childhood home. 1411 Mohapi Street would later grow into my Plastic Crown series, but I see 1411 being more intimate than Plastic Crowns.

BM: Speaking of ‘intimacy’ and things a little personal, in Plastic Crowns one of the most memorable aspects is your use of multi-coloured balloons in the images as well as the exhibition space. I understand these are symbolic of multiple sexual partners—of which your grandmother disapproves. Can you tell me a little bit about this element?

PK: Balloons are the freest things I know—you just let them go and they are gone. The balloons are a so-what-if-I-did part of the work; suppose I did have multiple partners, so what?

My gran would conclude a lot of things for herself including telling people that I was lesbian. This happened because a friend slept over one night in the same room as me, and my gran made assumptions about me and my sexuality. I remember this happened soon after a woman was killed in Naledi township for being a lesbian and I was deeply upset that someone who was supposed to care about me and look out for me, would do that and put me in potential danger. [5] So, the balloons are an element of ‘Let’s Say I did, Let’s say I AM, now what?’

In high school I thought I liked an Indian girl in my class but then I realised I’m not a lesbian, but that I was in love with the way she carried herself, the way she dressed, her confidence … she had amazing qualities that I really admired and connected with. This whole experience helped my thinking around Plastic Crowns and connect with my gran’s ideas of what it meant to be a good woman—ideas like cleaning and domestic work.

My partner and I were actually talking to our daughter about this last night. When you call someone a ‘woman’ you prescribe what society has said a woman is, and it limits that person. If that person deviates from that then they are seen as a problem. I think that’s what I was ultimately trying to do with Plastic Crowns—not just questioning gender and sexuality but questioning how we learn to be human. Since the birth of my daughter these feelings have intensified, but Plastic Crowns was really taxing on me and halfway in I hit a brick wall. I was tired of looking through the clothes and dresses and myself and everyone around me. I started feeling like I was suffocating, I needed a break. That’s how my Lady-Zile series came to be. There really isn’t a story there, I wish there was. I just needed a break and to focus on something different.

BM: Can you tell me about your experience of creating Plastic Crowns during the 2015 Gisele Wulfsohn Mentorship in Photography?

PK: To be honest, I never thought I’d get the mentorship, because when I read up on Gisele I was like ‘no ways am I getting it!’ but that’s when I discovered that activism isn’t only about documenting and being in the front lines. I learned that this girl from a small place like Moletsane in Soweto also has a voice, and that I am allowed to share it. [6]

The mentorship was a crazy time, but I wouldn’t change it. Initially there was difficulty in getting a consensus on who my mentor should be. Everyone had ideas about who would be the best fit and eventually I was like ‘I’m going with Ayana and that’s that.’ Ayana was a great mentor—she taught me so much more than how to take photographs or how to present yourself in professional settings. [7] We started a friendship beyond the studio and even now the mentorship is over we are still working together. I am involved in a residency program with her starting soon—I don’t know all the details yet but it’s very exciting!

I think I approached the mentorship in the same way I approached my job as Musa Nxumalo’s assistant. I went in asking questions: ‘What happened to you?’ ‘How did you get here?’ I’m interested in what they are thinking and the space they were in when they come up with their project ideas. I go into these things without expecting anything. I don’t go in with my CV or wanting a job. I just want to learn as much as I can and there is something special about connecting with people at the height of their success.

Ayana and the mentorship definitely helped launch my career and took me from student to professional, and I’m always grateful for that. I was also honoured that Plastic Crowns became the first exhibition showcased at the new Market Photo Workshop by a young black female. I think Gisele would be proud of that. I think, beyond the work, Gisele and I would have probably gotten along very well. I love what she stood for—there’s a lot I can tell through a person’s photography. I am honoured to be a part of that.

The truth is I still think the art industry in South Africa is small and very much still in the same hands, we definitely need to create more platforms not only to showcase our work, but [also] to own. Mentorships are really important, but capital is really the only thing that can help women, people of colour, and the queer community compete on the same level as everyone else. I also think artists give of themselves more than they received in return. I know a lot of great artists who are still not where they need to be, and the reality is living off art is hard in this country.

Notes:

[1] An image of this peach tree (from the 1141 Mohapi Street series) can be seen on Khanyile’s personal website: https://phumzilekhanyile.portfoliobox.net/1411mohapistreet

[2] One image from this collection—an image of Khanyile as a child, crying in the bathroom—can be seen on her personal website: https://phumzilekhanyile.portfoliobox.net/phumzilekhanyile

[3] Bonzon (2018a, 2018b) argues Khanyile’s use of fabric to create grains and the application of digital blurring techniques—what she refers to as ‘visual noise’—are ‘a political and visual strategy to materialise patriarchal norms, revisit familial heritage and colonial memory.’

[4] Where’s Wally? is a series of children’s puzzle books first published in Britain in 1987. In an attempt to localise the books for international audiences, Wally’s name was changed depending on the target country. In South Africa it was published in English as Where’s Wally? and in Afrikaans as Waar’s Willie?

[5] It is unclear whose death specifically Khanyile is referring to but, arguably, the most publicised murder of a lesbian in Naledi was that of Lerato Moloi on 14 May 2017. Moloi had been raped, stabbed, and then stoned to death in a field. Photographs of Moloi’s almost-naked body were widely circulated on social media denying her and her family dignity in death.

[6] Soweto is a syllabic abbreviation for ‘South Western Townships’ and comprises approximately 30 smaller townships. Moletsane is one of these smaller townships.

[7] For more on the mentorship program and to hear feedback from Ayana V. Jackson and mentorship administrators, see Market Photo Workshop (2017).

REFERENCES

Almino, Elisa Wouk (2017), ‘Learning Political Lessons at the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair’, Hyperallergic, https://hyperallergic.com/376880/learning-political-lessons-at-the-154-contemporary-african-art-fair/ (last accessed 7 October 2021).

Bonzon, Julie (2018a), ‘Noise: The Re-materialization of the Digital in Phumzile Khanyile’s Photographic Series Plastic Crown (2015-2016)’, in Agile Objects: The Art and Anthropology of Re-materialization, Clore Centre, British Museum, 1-3 June.

Bonzon, Julie (2018b), ‘Photographic Disruptions of Womanhood and Domesticity in South Africa’, in Noise, Octagon Forum, IAS, UCL, Event co-organised with Elizabeth Went, 29 June 2018.

Dee, Christa (2017), ‘Self-discovery through Imagery—Plastic Crowns exhibition by photographer Phumzile Khanyile’, Bubblegumclub, https://bubblegumclub.co.za/photography/self-discovery-imagery-plastic-crowns-exhibition-photographer-phumzile-khanyile/ (last accessed 2 August 2021).

Market Photo Workshop (2017), ‘Phumzile Khanyile Gisele Wulfsohn 2015’, YouTube, 08:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5fmaeJZOCg (last accessed 2 August 2021).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey