Regarding Violence: Du Côté de la côte and Varda’s Politics of Disregard

by: Colleen Kennedy-Karpat , November 7, 2023

by: Colleen Kennedy-Karpat , November 7, 2023

Agnès Varda’s short documentary film Du Côté de la côte (Along the Coast, 1958) was commissioned by the French Office National du Tourisme to promote France’s glamorous Côte d’Azur as a vacation destination. At certain moments, Varda showcases the coast in whimsical detail: here, in a study of foreign tourists’ swimwear and colour preferences, there, in a bit of wordplay in the voiceover narration. But in the Carnaval sequence, the film abandons its light-heartedness to frame the community festival as a tradition that promises fun but portends a specifically gendered violence enacted by men on women. This essay presents a close reading of the Carnaval sequence in Du Côté de la côte in comparison with Jean Vigo’s city symphony À propos de Nice (1930), which also represents Carnaval using rich visual and thematic detail. My aim with this close reading is to identify and define what I will call Varda’s politics of disregard: formal signals that establish her cinematographic practice as the basis of an evolving feminist project of responsible visibility. I then turn to another example in her late documentary Les Plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008) to show how this politics of disregard resonates throughout her filmography.

My use of the term ‘disregard’ contains within it the paradox of drawing attention to something whilst also ostensibly claiming that this same object, event, or idea is not worthy of attention. As I will show, this disregard is emphatically not a lack of care. It is necessarily preceded by an act of looking, which constitutes disregard as a conscious refusal of further engagement. What is disregarded must thus be acknowledged before it is just as deliberately set aside—though what is disregarded is probably (and importantly) not forgotten. Indeed, it may be temporary, flagging something to be taken up more closely in another way or in a different context. Yet the constructed, contingent absence that results can also render the disregarded object all the more present—even omnipresent—despite the conscientious foregrounding of other objects or ideas. The politics of disregard thus becomes possible in film when its audience is made to see something that the filmmaker does not intend to valorise. This requires, first, the recognition that representation per se is not equal to endorsement: the visualisation of objects, events, or situations that are not always ‘named’ can allow a filmmaker to acknowledge their social reality. Formal disregard can then open the film to the presentation of such material without linking its purpose to an explicit commentary. Acknowledgement through form distinguishes disregard from ignorance or denial, though, as we will see, disregard, like denial, can serve a range of ideological purposes. Notably, it can play an integral role in crafting the means by which progressive art gives form to what Toni Morrison has identified as a process of choosing one’s battle.

In a 1975 speech delivered at Portland State University, Morrison urged antiracists to deploy selective engagement with discourses of racism, whose ‘very serious function is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.’ She described the ‘prison of reacting to racism’ as a kind of mental entrapment that can only be avoided by refusing to comply with racists’ endless requirements for proof of humanity. Faced with the impossibility of satisfying their demands, Morrison argues ‘you don’t waste your energy fighting the fever. You must only fight the disease. And the disease is not racism.’ Nor (we might extrapolate) is it sexism: ‘it is greed and the struggle for power’ (Morrison 1975). She does not address the role of violence in maintaining these systems of power, an issue relevant to both racism and sexism, but her point is that intellectual efforts must focus on the root problem as opposed to tangents that drain energy without bringing anyone closer to a solution. And art, she insists, can accomplish this goal. ‘All of the best art is political,’ she continues; ‘it has to do with the society and what’s wrong with it, and methods for its correction’ (Morrison 1975). Varda’s disregard operates in precisely this sense, underscoring problems with pressing personal and social consequences, yet recognising that addressing them more directly would neither cure the social diseases she has diagnosed nor advance the line of inquiry she aims to pursue in a given film.

In representing Carnaval in Du côté, Varda uses form and tone to acknowledge violence against women yet sets aside this violence as a defining aspect of the Côte d’Azur. Marking a disjuncture between the intended mood and the actions that are captured on film, this discrepancy invites analysis along the lines of disregard, which ultimately shapes Varda’s commentary on gendered violence. This essay will not extend a detailed account of disregard across Varda’s filmography, but will focus on two documentaries poised at either end of her long career. The documentary approach arguably positions this formal strategy closer to unmediated feminist praxis, yet facets of violent and/or criminal sexual encounters are also realised and variously disregarded in Varda’s feature films, including Les Créatures (The Creatures) (1966), Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), and Kung Fu Master! ((1988). No matter the genre, her restraint in representing sexual violence never dismisses what takes place, even as her representations disregard many of the real and weighty consequences of these actions. Generally speaking, then, Varda’s disregard serves two functions: firstly, it emphasises that women are not defined by their victimhood—nor, more controversially, by their role in perpetrating sexual crimes, as in Kung Fu Master! —and secondly, it proposes an empathy rooted in shared experience as an alternative to sensationalist anger.

The disregard that Varda enacts through form in Du Côté de la côte suggests that this violence forms a backdrop to every woman’s life, not only during Carnaval and not only along the southern coast of France. Such experiences are unfortunately not so limited in time and space. Indeed, gendered violence in Varda’s oeuvre creates a taxonomy of misogyny that recognises and realises on film the near-constant pressure such threats can exert on people’s lives. Yet by disregarding such misogynistic violence, Varda refuses to grant it the power to define the feminine experience. In life, of course, facing chronic disregard provokes immense frustration. Experiencing the disregard of actual social structures forms a major impetus for the feminist movement and other progressive causes, as Varda shows through several examples in Les Plages d’Agnès. In one such instance, when discussing the abortion rights activism of the 1970s in France, Varda pronounces: ‘J’essayais de vivre un féminisme joyeux, mais en fait j’étais très en colère,’ which has been subtitled in English and captured in still frames as ‘I tried to be a joyful feminist, but I was very angry’ (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1. ‘I tried to be a joyful feminist.’

As this duplication indicates, versions of this image have become a meme circulated online to mark Varda’s personal milestones such as her birthday (Fig. 1, upper) as well as more general events like International Women’s Day (Fig. 1, lower). The spirit of the comment captures the oscillation between the joyful solidarity and deeply rooted anger which both prompt women to take action. Unfortunately, to be disregarded as a person, or to have our own experiences disregarded, is common and relatable enough that representing it becomes a necessary problem for certain narratives to come to life. With reason, Varda’s own declaration is intercut with segments of Sans toit ni loi, which explores this social disregard in depth, and key moments from L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t) (1977), her quasi-musical exploration of feminist activism in France. But narrative disregard is not an endorsement of social disregard; quite the contrary: representing disregard can offer pointed critique of how such inconvenient truths are handled. Incorporating disregard into both documentary and fiction films, Varda establishes disregard as a sort of politics, an approach we can track across her collected works. The cumulative weight of the regard touching on the same subject highlights the irony at the root of this politics. We know what we’ve seen whether or not a filmmaker further acknowledges or offers a road map to navigate its repercussions. Varda trusts her viewers to note these observations, and wrestle with them independently.

Another caveat, equally crucial, is that the regard may only perceive a fraction of the actual problem. This, in turn, limits the scope of the disregard revealed or underscored through the work. As Jennifer Stob has argued, Varda overwhelmingly presumes a formally rigid gender binary in her work, a presumption that extends to her representations of violence. Her tendency to focus on ‘selves and bodies like her own: white, European, middle-class, cis-gendered, and invested in heterosexual hegemony’ necessarily results in a partial understanding of what, exactly, society tends to render invisible (Stob 2022: 16). Varda’s filmography grants only the barest regard towards queer issues, for example, despite her beloved husband Jacques Demy’s painful decline and eventual death from AIDS in an era when it was widely stigmatised as a gay men’s disease. Still, her framing of interpersonal violence as systemically grounded in gendered hierarchies holds insights that apply beyond the formally inflected binaries that undergird her films.

Du Côté de la côte: Violence, Privilege, Rage

With these caveats firmly in mind, what follows is a sample application of Varda’s disregard to the representation of gendered violence in Du Côté de la côte, detailing what Varda shows us—her regard—along with how and to what ends she constructs her film’s disregard for the same. Disregarded in Du côté is how public assaults on women are an unsurprising, even expected component of a traditional cultural festival. A range of assaults are captured on Varda’s camera, but their full weight is disregarded through formal structures that include voice-over narration, editing, and cinematography.

These approaches and their role in framing disregard emerge even more clearly in comparison with similar films, some of which Varda cites more or less directly in Du côté. Examining what he calls Varda’s ‘applied cinephilia’—that is, her propensity for citing other films in her work—Tim Palmer contends that Du côté ‘re-enacts the frenzied carnival of Jean Vigo’s À propos de Nice (1930)’ (2022: 87). While both filmmakers are taking on the same geographic subject, the claim that she ‘re-enacts’ Vigo’s experimental city symphony rather overstates Varda’s debt in terms of her style and her goals for the film. Beyond its origins as a commissioned work to promote tourism, Du côté frames a critique of popular culture that expands Vigo’s focus on class by adding gendered layers and setting gender apart as its own concern. Taking Vigo and Varda’s films together, comparing their formal approaches to Carnaval prompts significantly diverging analyses. The critical convergence of gender and violence amidst ‘the frenzy and exhaustion’ of Carnaval forms the crux of the sequence offered here for close reading (O’Neill 2019: 102).

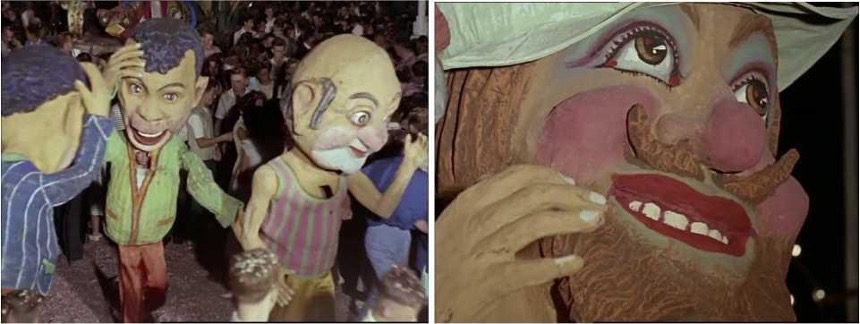

Vigo’s treatment of peak Carnaval celebration begins at ground level with the parade, where high and low classes mix in the gathered crowd. The parade is also where he situates the géants processionnels: portable, gigantesque figures based in folklore, generally humanoid in design, with occasional animal géants as well (Fig. 2). They are more closely associated with Carnaval traditions in northern France and in Belgium [1], but are also part of festivities elsewhere, including France’s southern coast. Vigo’s géants—among which are many racist caricatures, which is not developed as a point of critique—are generally shown in groups, in daylight, and at some remove from the attending crowd (left), with multiple examples of a single type occupying the same frame. The head pictured here (right) is one of the film’s most fantastic designs, and one of the rare instances where a single géant occupies the frame. The géants are filmed from various angles: from a low angle that captures or even exaggerates their towering height, from above, and at street level.

Fig. 2: Vigo’s géants.

Fig. 2: Vigo’s géants.

Following the parade, Vigo shows the merriment of human revellers. Using camera speed to represent a sort of altered state, Vigo creates ‘a dream-like sequence’ that underscores certain ideas about Carnaval as a vehicle for popular escapism rather than a more critical, lived experience of the event (O’Neill 2019: 103). Vigo anchors this sequence with repeating shots of a vivacious group, made up almost entirely of women, situated on a platform literally above the fray (Fig. 3). In his commentary track on the Criterion Collection DVD release of À propos, Michael Temple points out that Vigo himself appears on the platform, and one of the dancing women is his wife. A few grotesque masks appear in the first shots of these women, offering a visual transition from the géants. But unlike the mixture of angles that capture the géants, the revellers are always filmed at low angle, though with variety in their vantage points and frame rate, including slow motion shots. The women look right into the lens, aware of the camera, yet they never seem to take its presence as an intrusion. Their movements appear spontaneous, intimate, and occasionally risqué—a sharp contrast with an earlier sequence’s staid, rigidly partnered ballroom dancing that Vigo associates with the city’s upper crust. The playful, flirtatious mood of these images is not to be taken lightly, as Vigo intercuts them with signs of death: military ships that point to colonial violence overseas; stark white funereal monuments. In juxtaposition with these memento mori, the montage conveys the resilience of their joy.

While Varda’s film differs from Vigo’s in its primary focus, she does not fully retreat from class conflicts. Delphine Bénézet underscores how Du côté ‘deconstructs some of the myths the Riviera is built on, and sheds light on the lingering gap between the more and the less privileged’ (2014: 98). Varda inscribes class most clearly on the allocation of space, emphasising gates and barriers—garden fences, hotel doors, café windows—that separate those who pass through them and those who do not. Importantly, this marking of public space is how Varda segues into her Carnaval sequence (Fig. 4). A series of street signs overtly indicate restricted access, and she captures two especially serendipitous juxtapositions: in one, a sign reading ‘Dream Heights’ is posted alongside one warning ‘No Outlet (Dead End)’ (left); another image uses standard signage to refuse entry to Eden Avenue (right). These images suggest a metaphorical content warning for what follows, opening visual parentheses on the sequence to be disregarded in the evaluation of the film’s overarching subject.

Rather than class, Varda’s Carnaval sequence centres gender as the key measure of privilege that determines experience. Women are present at the celebration, but as victims of assaults that range from the mildly irritating, like throwing confetti, to forcibly violating—while men are depicted as their victimisers. This sequence offers a study of systemic sexism, showing what women endure for ‘fun’ under the guise of tradition, while its formal differences compared to the rest of the film cultivate a conscientious disregard for these harrowing conditions. Formally, Varda signals this disregard most clearly by withdrawing the film’s contextualising voice throughout the Carnaval sequence. Up to this point the visuals had, from the very first shots of the film, been accompanied by two voices—one coded male, the other female—but neither is given anything to say about what transpires at the Carnaval ball. Just before the camera descends into the tightly packed gathering, the male voice declares ‘De la nostalgie naît le carnaval (Carnaval is born of nostalgia)’ [2] before falling silent, leaving a lingering question: nostalgia for what? Are Varda’s revellers seeking some paradise lost, or one that lies out of their reach? Comparisons to the biblical garden of Eden abound in Du côté, but what we see during Carnaval hardly presents a rarefied idyll.

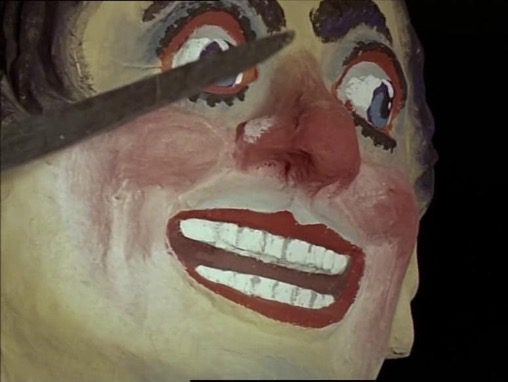

In contrast with Vigo’s otherworldly Carnaval, Varda demonstrates the festival’s harsh mundanity by bringing her camera unflinchingly close to her subjects, human and nonhuman alike. As in À propos, Varda puts the géants processionnels on full display, but in contrast to Vigo’s dispassionate observation, she invests these gargantuan caricatures with a more immediate sense of horror. Close-up framing dominates her shots of the géants, and even with some distance she frames them much more tightly than Vigo does in his parade shots. Compared to Vigo’s fantastical géants, in Du côté they retain an element of grotesquerie while caricaturing more quotidian human forms (Fig. 5). In passing, we might note the absence of overtly racist imagery among Varda’s géants, but Varda also shows several animalistic géants—particularly rats—composing and editing these shots to align them suggestively with human men (Fig. 6).

Nearly all of the humanoid géants are coded masculine, except one: an elderly woman wearing a headscarf and an expression that combines sorrow with concern. This female-coded géant appears more than once, her movement and facial expression positioning her as a symbolic witness—but to what? It could be any number of violent acts; the party’s human men are no less grotesque than the géants, but in their actions as opposed to their appearance. In stark contrast to Vigo’s freewheeling revellers, the women at Varda’s Carnaval seem to let down their guard only in the rare moments in which they share space in the frame with one another. The seemingly constricted space—there are often fences in the background—and the darkness that surrounds the outdoor venue combine with Varda’s tight framing to obscure the full dimensions occupied by géants and party goers alike. The editing darts around this space, but never seems to leave it until the burning effigy marks the end of the festival. Du côté thereby conveys an intense feeling of forced proximity to others, especially strangers, and reflects the anxiety that this proximity can evoke, particularly among people who are vulnerable to unwanted contact. Indeed, Varda’s camera captures assaults on women that provoke varying degrees of distress, some of which are very difficult to screenshot because they pass so quickly (Fig. 7).

The sequence’s most extreme reference to violence comes as the editing points the female géant’s gaze towards another géant whose poised blade and deranged visage threaten bloodshed (Figs. 8a-f). While this behaviour is not associated with an actual person, Varda’s six-shot montage offers up a human victim: a woman isolated in the frame and seemingly out of harm’s way. But this sense of protection is dispelled by a leering tilt downward over her body (Figure 8a), which turns out to be less clothed than first glance might suggest (Fig. 8c). This shot—which, notably, also moves the woman’s head out of frame—is intercut with a close-up of the géant (Fig. 8b, 8d), filmed in a horizontal left-to-right pan that centres the path of the knife. The intersecting trajectories of the moving camera are as suggestive as the juxtaposition of these subjects, creating through form the murderous levels of violence that Varda cannot or would not depict outright. In the midst of this symbolic stalking, the headscarved géant reappears (Fig. 8e). This time, the camera lingers a bit longer as she turns, seeming to follow the knife with her gaze. This cinematography and the shot’s placement in this sequence connect the act of witnessing to this implicit threat. The transitional cutaway from the witness reveals a lizard géant (Fig. 8f), which both defuses the tension and, once again, visually aligns man with animal, this time just before turning attention to the actual human assaults captured on camera (of which Fig. 7, above, shows two examples). Notably, the film shows no consequences for any of its represented acts of violence beyond the fact that they have been seen. In this sense, the lone female géant can be understood as a proxy for Varda’s own gaze, which regards with grief and trepidation the violence that transpires at Carnaval yet refuses to elaborate on its meaning or to offer any direct response.

At the end of the Carnaval sequence, Varda’s spectacular, explosive effigy (Fig. 9, left). suggests the dangerous culmination of long-simmering rage. The contrast with Vigo’s more deconstructed composition (Fig. 9, right), which frames a discarded head among other detritus, could not be clearer. At the end of his film, Vigo bookends his géants on parade not with a burning effigy, but with an abandoned and inverted visage de géant intercut with shots of smokestacks and controlled flames that merely allude to destruction. His emphasis seems to be on the difficult labour undertaken after dreamlike revelry, showing in the final sequence a series of close-ups on working men. Varda’s conclusion, on the other hand, feels vengeful, her camera framing fiery destruction at frighteningly close range.

Without a voice to guide the visuals, the violence unleashed in the Carnaval sequence is presented instead in counterpoint to music: an upbeat, celebratory march, possibly recorded on-site, as the audio quality departs from that of other music in the film. The voices that until this point have made sense of the images by locating them geographically and contextualising their meaning have either abandoned the viewer or been drowned out by the oblivious marching band. Varda’s disregard is most legible in this conspicuous refusal to verbally address what the film has just repeatedly shown and is further reinforced in the language used when the narration finally resumes. As the camera cuts in, then even closer on the fire that engulfs the king of the géants, the music turns cacophonous, then mournful, and then the male voice chimes in over these last, fiery visuals:

Carnaval brûle. La terre tremble. Le soleil s’affale. Les eaux se reforment. Carnaval est mort, le silence va régner. Le silence en réponse à tant de questions: en réponse aux volcans, aux tourbillons. (Carnival burns. The earth shakes. The sun sets. The waters settle. Carnival is dead, silence shall reign. Silence in response to so many questions: in response to volcanos, to whirlwinds)

Rather than unpack the significance of the violence on display, the narration turns away from human concerns entirely, as the visuals show extreme long shots of the sea and surrounding nature. And the silence in response to Carnaval is not just any silence, but a dominant one that can withstand the most uncontrollable forces of nature. Silence, then, may be the only possible response to the violent entitlement on display during Carnaval. Varda’s hand has been forced, perhaps—this is, after all, a film ostensibly meant to attract tourists! —but the least she can do is show this violence, however fleetingly, even if silence is the only possible riposte.

Once the Carnaval sequence has given way to nature, the film moves towards its conclusion. A series of shots sweep over the coastal landscapes, then the woman’s voice gives the film its final word:

La nostalgie de l’Eden, c’est un jardin. Ce n’est plus la Côte d’Azur, c’est un jardin transplanté, c’est une idée de jardin à fleur, à pelouse, à colonne … Si ces rêveries sont collectives, les jardins ne sont pas publics. (Nostalgia for Eden: that is a garden. No longer the Azure Coast, it’s a transplanted garden, an idea of a garden with flowers, a lawn, columns … Although these dreams are collective, the gardens are not public.).

This final message—delivered by a voice whose main function until this point had been to name locations—is that shared mythologies cannot guarantee a similar experience. Gates both literal and figurative are everywhere, shutting people out and/or shuttling them through the Côte d’Azur along whichever path their social status has predetermined for them. Women can expect to confront unsavoury behaviour from men, who apparently glide along a different track; these women, like Varda herself, will be expected to discount this as part of the total package. But Varda cannot help but see it, and with her camera she documents her observations. This subversive depiction of a lack of access and the dangers of full participation in local culture makes Du Côté de la côte something beyond, perhaps even something other than a straightforward, commissioned advertisement. [3]

Silence & Social Disregard: Les Plages d’Agnès

Although Varda approaches sexual assault and gendered violence in other ways in other films, centring the question of disregard can shed light on the unique profile of each iteration while accumulating broadly applicable insight into Varda’s feminist project. Her late documentaries offer some of the most highly developed articulations of her politics of disregard, showing how she came to deploy this strategy even in narrating her own life experiences. Her overtly autobiographical Les Plages d’Agnès presents ideas and events she demonstratively sets aside or plows through in order to focus more purposefully on what matters to her, thereby using disregard to define her vision of what matters to feminist action.

Perhaps the most trenchant example of disregard in Plages involves gendered violence, as Varda recalls the flasher who lived in her neighbourhood. Within a broader recollection of her formative years, Varda includes a comically hyperbolic reenactment of a typical encounter with the flasher. Deploying what Claire Boyle calls the ‘cartoon-style mise-en-scène’ of reenacted memories in Plages, Varda conjures a playful tone to reimagine a jarring aspect of her childhood (2013: 162). Through exaggerated performances and an even more exaggerated prosthetic that adds ludicrously unnatural spring to the exposed genitals, the ridiculousness of the reenactment undercuts the violence of the act it represents. This making light of a real, common enough form of gendered aggression contributes to Varda’s politics of disregard by using humour to defuse the act itself and shifting the crux of her argument to the community’s lack of response.

In the four shots that comprise the flasher sequence, Varda’s withholding of language operates as a form of disregard that gives way to broader arguments about the responsibility to observe and take action (Figs. 10a-f). The opening shot (Fig. 10a) tilts up from Varda’s sandals to her head, showing the city hall stairs in the background behind her. As though narrating her own inner monologue, Varda tells us in voice-over, ‘Je me souviens bien de ce quai. C’était notre cour et notre jardin (I remember this wharf quite well. It was our courtyard and our garden).’ The next shot uses a moving camera to allow the action to unfold in three key moments (Figs. 10b, c, d). First (Fig. 10b), the camera tilts up to show a girl standing at her hopscotch game, then pans left to right to follow her jumps in the foreground and to reveal in the background two women with a stroller. Here, still in voice-over, Varda sets the stage: ‘Une petite scène s’y jouait très souvent (A brief scene would play out here very often).’ Then (Fig. 10c) a flasher appears in the women’s path, opens his trench coat, and the camera stops with him centred in the frame before reversing the pan, as the girl in the foreground turns around to cross the screen. There is no narration of this action. The women gasp audibly before turning themselves and their pram around, while the girl, presumably the same age Varda would have been, sustains for a moment her full (if uncomprehending) gaze on the flasher, who stands at some distance and is not deliberately targeting her. The shot concludes (Fig. 10d) with the women exiting frame left, while in the foreground, the girl also jumps left and out of frame as the flasher closes his coat and climbs the stairs. Varda remarks in voice-over, ‘On ne s’occupait pas de lui (No one dealt with him).’ The next shot (Fig. 10e) shows an actor portraying Varda’s mother in extreme long shot, without camera movement. Varda continues in voice-over, ‘Et maman, juste en face du palais, lavait ses six pairs de draps et ne voyait rien (And just across from city hall, my mother would be washing six sets of sheets and didn’t see anything).’ Finally (Fig. 10f) Varda cuts in, changing the angle slightly while tightening the frame, and concludes her commentary: ‘Elle n’a jamais rien vu (She never saw anything).’

Through mise-en-scène, Varda shows how the flasher’s actions do not amount to a life-changing affront—still, what sticks in her memory is her community’s indifference. Varda herself saw this happen—apparently many times—as did many others; she learned even as a child to disregard the act itself. She includes it here firstly to demonstrate her own disregard, expressing this primarily through the anti-realist embellishment of her staging, yet this sequence also raises the more troubling idea that many others either did not see it or would never admit to seeing it, let alone take measures to stop it. Varda states that her mother never saw what happened, although the way she films her mother’s proximity to the scene casts doubt on this. But can feigned ignorance be (dis)proven? Failure to act against a witnessed offense amounts to a real and not unlikely social disregard for the flasher’s many victims, but is there culpability in actual ignorance?

Varda’s most pressing point stems from the ability to take advantage of this murky zone in which ignorance fuses with inaction. More haunting than the creep on the street is the ambiguity of her mother’s non-acknowledgment, which obscures whether she never actually saw the scene play out, or just wanted to avoid addressing it. Varda formulates this question through form and language just as she had done fifty years earlier in Du Côté de la côte. As with the violence at Carnaval, we see both the flasher and the women reacting to him, but Varda narrates neither his act nor their reaction. Instead, what she describes—and what becomes the point of the entire anecdote—is her mother’s silence. Repeating the claim that her mother never saw the flasher while doubling the shot of her on the boat suggests Varda’s doubts about this account. If it’s true that the flasher would lurk beside the entrance to city hall (!), situated directly across from where her mother used to do the washing—a chore that, to be fair, would require focused attention and strenuous labour—it nevertheless defies belief that anyone could have been so oblivious to a lewd, public act that happened ‘very often’ on the quay where their own children were playing.

Varda further links the flasher to her presence in that space by recalling a more innocent detail of her childhood: the lifebelt she wore while on board the houseboat (Fig. 11). The gangplank that (appropriately enough) provides a transition between the reenactment and her childhood memory situates the far corner of city hall in the background; meanwhile, the same spot where Varda staged the flasher is shown in the background of Varda’s vintage photograph of herself as a child, wearing the lifebelt she talks about in voiceover. Varda’s narration may have moved on to a different memory, but the visual repetition of that space retains a lingering shadow of the unspoken act that precedes it in her film.

Varda’s insistence on the invasive nature of these traumatic memories demonstrates the need for our communities to observe and respond to these kinds of disruptions as they happen. Failing at this task amounts to an abdication of responsibility and a breach of trust whose lingering effects can prove more consequential than the initial disruption. ‘On ne s’occupait pas de lui’ criticises a community unwilling to assume this responsibility; at a more personal level, ‘Elle n’a jamais rien vu’ takes aim at a more devastating target, suggesting a general lack of maternal protection couched in a refusal to acknowledge what was happening in plain sight. The flasher sequence in Plages thus uses formal techniques of disregard to encapsulate its cost as an actual social practice, emphasising its profound effect on interpersonal relationships that are supposed to be built on trust and care.

In itself, reenacting the city hall flasher, a memory that is silly and disturbing in roughly equal measure, is not especially valuable to Varda’s self-narration or to her feminist project. Its significance stems instead from the flasher’s impunity within a social system that insists on not seeing a transgression that regularly, maybe even predictably disrupts the peace. Varda’s politics of disregard ensures that her audiences can no longer claim not to see what Varda has so plainly projected before us. Unable to feign ignorance, we might choose to deny what we see (that is, what she has purposefully included so that we see it), or else we accept Varda’s invitation to disregard it as she elucidates more crucial observations about why this aspect of gendered existence has remained stubbornly invisible in the first place.

Varda’s disregard underscores the critical importance of seeing, of recreating moments and representing people that inflict harm. Varda’s tendency to visualise a range of gendered violence, even when it makes up only a tangential component of a broader arc, forms the core of her politics of disregard. Visibility is important to her, and her documentaries share what she has seen through direct representation, as we have seen here in Du Côté de la côte and Les Plages d’Agnès. Likewise, Varda’s fiction films also frame disregard by representing social systems that render certain actions and behaviours invisible. What Varda disregards in and through her films becomes an integral part of what we see, even if she does not engage it beyond the validation of cinematic representation. Systematic forces are constantly shaping our lives, but disregard means that we need not allow what these systems inflict on us—no matter how horrific—to define us. Our actions (and inactions) matter at least as much as our experiences, even if our experiences are what provoke us to act.

Aligned with the spirit of Morrison’s (1975) crucial advice to engage only with deliberation and care, Varda’s disregard aims to shepherd the audience towards more effective methods for social correction, based on her understanding of the problems we face and her abilities as a filmmaker to represent them. Her overarching goal is to focus our conversations and actions on the changes that will have the most impact, on what Morrison (1975) framed as fighting the disease rather than disguising, downplaying, or denying its symptoms. As feminists, Varda insists that we must not forgo the pleasures of solidarity, even if we feel the pressing weight of the myriad injustices there are to fight, and even if we see the peril in a particular course of action. There are points of darkness that can overpower the light that shines on the bigger picture. The accuracy of Varda’s vision and the effectiveness of her strategy, rooted as they are in various forms of social privilege, merit further debate. But ultimately, Varda’s politics of disregard emanates a kind of optimism, acknowledging why we have every right to our anger while insisting that we can—we must—save our best energy for joy.

Acknowledgements:

In memoriam Alan Williams (1947-2023), early and steadfast champion of Varda’s work in the context of French cinema history.

Notes:

[1] Géants are also a key element of the Belgian film Quand la mer monte (2004), the directorial debut of Varda veteran Yolande Moreau, where they are presented as a practice designated by UNESCO as part of that region’s intangible cultural heritage.

[2] All translations are my own unless otherwise stated.

[3] Varda’s short film found a respectably wide audience and was screened in the company of some of her peers’ best work. Kelley Conway (2015: 31) reports that it was programmed in French theatres alongside Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959), a classic mid-century arthouse film that sold over two million tickets, hitting just below the threshold for France’s top twenty feature releases of 1958 (Simsi 2000: 28 & 75).

REFERENCES

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, London: Wallflower.

Boyle, Claire (2013), ‘“La vie rêvée d’Agnès Varda”: Dreaming the Self and Cinematic Autobiography in Les Plages d’Agnès,’ in Fabien Arribert-Narce & Alain Ausoni (eds), L’Autobiographie entre autres: Écrire la vie aujourd’hui, Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 149-166.

Conway, Kelley (2015), Agnès Varda, Urbana: University of Illinois.

Morrison, Toni (1975), ‘A Humanist View’, speech delivered at Portland State University, 30 May 1975, transcription available https://www.mackenzian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Transcript_PortlandState_TMorriso n.pdf (last accessed 5 March 2023).

O’Neill, Rosemary (2019), ‘Agnès Varda’s Du Côté de la Côte: Place as “Sociological Phenomenon”’, in Catherine Dossin (ed.), France and the Visual Arts since 1945: Remapping European Postwar and Contemporary Art, New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 93-105.

Palmer, Tim (2022), ‘Beside Du Côté de la côte (1958): Agnès Varda’s Early Applied Cinephilia’, Short Film Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 77-91.

Simsi, Simon (2000), Ciné-Passions: 7e art et industrie de 1945 à 2000, Paris: Dixit.

Stob, Jennifer (2022), ‘Agnès Varda’s Formalist Feminism’, in Colleen Kennedy-Karpat & Feride Çiçekoglu (eds), The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda: Feminist Practice and Pedagogy, London: Bloomsbury, pp. 15-28.

Films

À propos de Nice (1930), dir. Jean Vigo.

Les Créatures (The Creatures) (1966), dir. Agnès Varda.

Du Côté de la côte (Along the Coast) (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

Hiroshima mon amour (1959), dir. Alain Resnais.

Kung Fu Master! (1988), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les Plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008), dir. Agnès Varda.

Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond ) (1985), dir. Agnès Varda.

L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t ) (1977), dir. Agnès Varda.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey