Mineral Memories: Photography & Disappearance in Argentina

by: Jordana Blejmar , June 25, 2022

by: Jordana Blejmar , June 25, 2022

The Argentine dictatorship was marked by repression, terror, and censorship. The military installed hundreds of Clandestine Centres of Detention and Torture. It is estimated that around 30,000 people were kept prisoner illegally in these clandestine centres, tortured and ‘disappeared,’ some thrown alive into the River Plate to drown, others buried in anonymous graves. Around 500 children—of whom only around 130 have been found so far by the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo—were illegally adopted or ‘appropriated,’ sometimes raised, in perverse fashion, by the murderers of their parents.

The military regime relied on a conservative, chauvinist, and politicised take on gender. The dictatorship affirmed that the only legitimate type of family was Christian, patriarchal, and traditional. The State was promoted as the Great Father, the nation as the ‘Great Argentine Family’ and the military as the ‘chosen children’ (Filc 1997: 50). Official discourse also represented citizens as immature children in need of discipline from a strict father (Jelin 2006: 178). As Elizabeth Jelin has argued ‘national myths are rooted in images and metaphors of traditional gender roles,’ such as the idea that women physically reproduce the nation, while men protect it: the ‘masculine heroism of the soldiers’ and ‘feminized image of the idealized motherland.’ In this complex dynamic, ‘the female body becomes the mother who gives birth to the sons of the nation, but also the place where the Other can be penetrated, hence the necessity of protecting and disciplining women’ (Jelin 2012: 344). In such nationalist discourse, typical of the authoritarian regimes of not just Argentina, but across the Southern Cone, the ‘impure’ children (the guerrilleros) were seen as the result of a violation of the nation.

Despite the links between gender and sovereign violence during the dictatorship, the specific experiences of gender-based violence were not part of public discourse in the immediate post-dictatorship period. Indeed, in the cultural climate of the 1985 Trials of the Juntas, ‘rape was part and parcel of torture. It was not seen as a specifically gender-related act. The main focus was on enforced disappearance as the epitome of State Terror … Compared to that, the rest seemed less important … At the same time, the rules of law and the cultural climate of the time saw rape as an affront to one’s ‘private honour’ (honor privado)’ (Jelin 2011: 344). It is not surprising, therefore, that the first conviction for sexual violence carried out during the dictatorship in Argentina dates only from 2010.

In recent decades there has been a consistent effort to recognise gender violence in the context of war and totalitarian regimes, not just in Latin America but worldwide. In 1993, the United Nations Security Council incorporated rape as part of its agenda when discussing the creation of the Yugoslavia Tribunal. In 2008, the Council recognised sexual violence as a matter of security, and unanimously voted in favour of a resolution that considered certain instances of sexual violence carried out against women and girls to be a tactic of war designed to dominate and instil fear in specific ethnic groups or communities (Jelin 2012: 345). Sexual and gender-based violence was common in Clandestine Centres of Detention and Torture. Only now, not least in the wake of the 2015 Not One Less feminist movement, this type of violence committed during the dictatorship is seen less as an attack on dignity or ‘private honour’ and more as a crime against humanity, and as a tool used by perpetrators to exercise terror and neutralise resistance. [1]

This article looks at the different ways, whether implicit or explicit, intentional or unintentional, in which the photographic work of Paula Luttringer (born in 1955 in La Plata, Argentina) bears witness to those who, like her, survived torture—including gender-based violence—during the dictatorship. The text is based on frequent video call and phone conversations that I had with Luttringer over the course of several months in 2021, usually in the afternoon after she had returned from the daily walks she started to take during lockdown in the south of France, where she lives. Luttringer is not only an accomplished and skilful photographer, but also a sharp reader of her own work. Her images document the legacies of the traumatic past and the remnants of clandestine centres of torture and extermination. But more than registering an exterior reality, her photographs allow us to witness a tiny fragment of the interior lives of survivors, especially women. With her camera, Luttringer captures not so much places but the (eerie) atmospheres that inhabit both sites of detention and torture and places seemingly unrelated to the dictatorship—a slaughterhouse, a dry forest. Photography becomes here an affective, and effective, tool of survival and resistance, and the means to weave together voices, gazes, and memories.

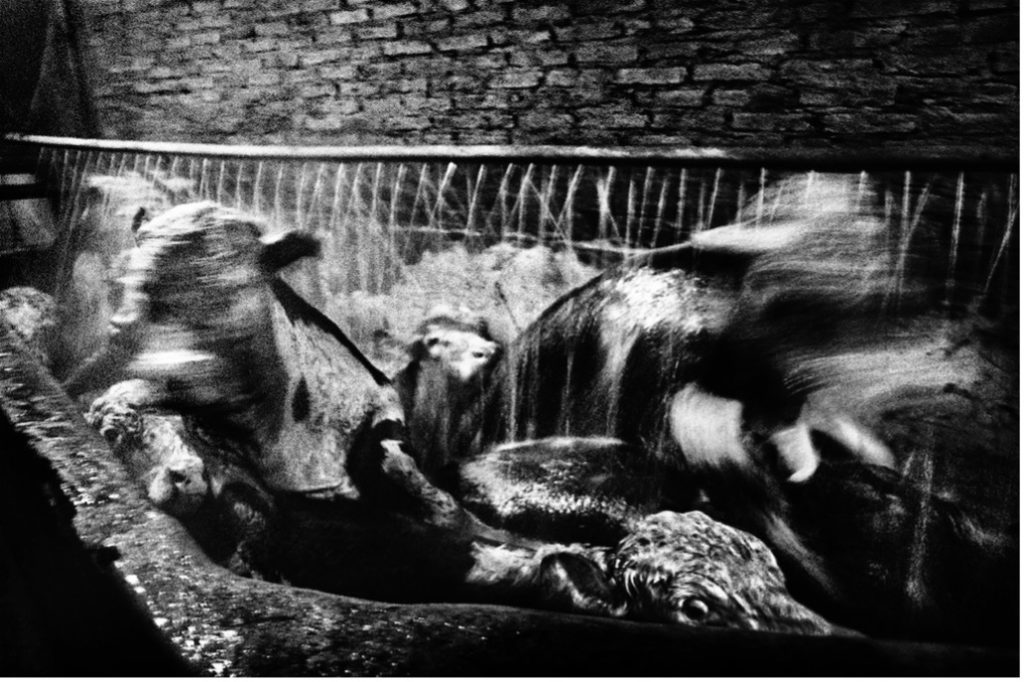

Bestial Violence

The Slaughterhouse (1995), Paula Luttringer’s first photographic project, is comprised of snapshots of various days in an Argentine abattoir (Fig. 1), the gaze focused on the desperate cows and the aftermath of their slaughter, their heads and legs hanging from cold chains (Fig. 2). Though these are black and white photographs it is almost possible to see and smell the red blood covering the dead bodies, almost hear the deafening metallic sound of the machines. The seriality of these images echoes the temporality of a storyboard or graphic novel. A game of lights and shadows, these blurry, fragmentary, and out-of-focus photographs create a sense of the uncanny, producing confusion in the viewer, not least because we cannot distinguish day from light, outdoors from indoors. The perpetrators/butchers are faceless. The uniforms and tools hanging from stained white walls evoke the administrative nature of murder, the bureaucratised massacre.

The Slaughterhouse was Luttringer’s her first photographic project. ‘I wanted to do work related to the Argentinian people,’ she explains, ‘and I thought of the beef industry … I had thought that this was all I was doing. But later, when I showed my photographs to my friends, they said that they could see I was actually telling my own story’ (Foster 2020). During her high-school years in the university city of La Plata, Luttringer was one of the leading members of the political organisation UES (Union de Estudiantes Secundarios/ Secondary School Students Union). She then joined the Peronist guerrilla organisation Montoneros. On 31 March 1977, a year after the coup, she was abducted by the military and held in the Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture (CCDT) known as ‘El Sheraton.’ She was seven-months pregnant. In June that same year she was taken, blindfolded, to a military hospital located in Campo de Mayo (she only found out the exact location in 2008), where she gave birth to her eldest daughter. She saw her daughter once before her child was taken away. She did not know whether she would see her again. Around July, she was blindfolded and led to a car, where her daughter was put into her arms. She spent July and August in the Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture with her baby. After five months, she was blindfolded again and put into a car with her daughter. She thought her captors were going to kill her, but she was sent to a civilian jail. The police told her that she had twenty-four hours to leave Argentina. She spent two years in Uruguay and then six years in Brazil where she had another daughter. She then moved to France, where she currently lives. In 2011 she gave testimony in the trials of those responsible for the abduction of babies during the dictatorship. In 2018, she testified against her torturers and on behalf of her friends and compañeros who are still missing. Her testimony was crucial for condemning the perpetrators, as she is one of the few survivors of ‘El Sheraton.’

In 1992, Luttringer returned to Argentina for the first time since going into exile. She lived there until 1998, when she returned to France. In 1993, she visited an exhibition by Adriana Lestido comprised of photographs of mothers in prisons and of their children. She realised that photography might be a useful medium to express what she could not say with words. She was forty years old, and had never studied photography, but Lestido encouraged her to join her workshop. She also joined a second workshop, led by Juan Travnik, a renowned Argentine photographer. The images of The Slaughterhouse evoke her life under terror, but they also resonate with what Luttringer has described as ‘the collective memories of many young people of my generation who had been kidnapped and ‘disappeared’’ (Foster 2020).

Luttringer’s work is part of a wider corpus of texts by contemporary writers (Martín Kohan, Carlos Busqued, Agustina Bazterrica) and artists (Carlos Alonso, Cristina Piffer, Sameer Makarius) that connect the image of the ‘slaughterhouse’ to the country’s violent history of dictatorships, read in these texts as a succession of butcheries, hauntings, beheadings, and sacrifices (Blejmar 2018). Esteban Echeverría’s short story ‘The Slaughterhouse’ (1871), widely considered to be the origin of Argentine literature, is a key reference for all these works. In Echeverría’s El matadero, a member of the Unitarios political party, representative of liberal and European values and symbol of ‘civilization,’ is taken to a slaughterhouse by the barbarian Federales, all supporters of the caudillo and dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas, Governor of Buenos Aires between 1829 and 1832, and again between 1835 and 1952. The butchers tie the Unitario to a table and rape him so violently that they end up killing him. This story connects political violence during the birth of the nation-state to the animalisation and ‘feminization’ of victims’ bodies.

Paula Luttringer’s The Slaughterhouse can also be read as an allegory of the way sovereign violence is always gendered. ‘My cows never look like bulls. There is no doubt to me that I am taking photographs of the female gender’ (Interview with the author, 6 December 2021). Nevertheless, while her entire work is marked by gendered experience of violence, that was never a conscious choice. ‘In the 1970s, we [women] were allowed to do everything. That was revolutionary about my generation and about our political project’ (interview 6 December 2021). Her aim was always to try to understand how survivors, including herself, deal with the pain of living after experiencing incarceration and torture. She quickly realised, however, that she could only do this in conversation with other women. When she started to interview survivors in 2000, she talked to one or two men, but in their accounts, they always used the words of the period prior to the coup, a discourse of politics and revolution. She wanted instead to hear the fissures and wounds in those accounts, and she was only able to find them in women’s testimonies.

‘I don’t blame men, though I am the one who was possibly incapable of interviewing them. At the same time, it is also true that women tell’ (Interview with the author, 6 December 2021). For Luttringer, women are extraordinary storytellers: ‘I remember my Lithuanian grandmother, how she used to tell me about her past. There is something very powerful about the role of women in the intergenerational transmission of histories within families. They speak about everything, with details and bravery. The things that the women survivors told me touched me profoundly’ (Interview 6 December 2021). In her meetings with survivors, Luttringer asks them about their lives after disappearance, about their physical and psychological wounds, what their relationships with men are like now, whether they have even spoken about what happened with their mothers (she does not ask about their fathers), and their children. It is an honest conversation between women, with no euphemisms or reservations.

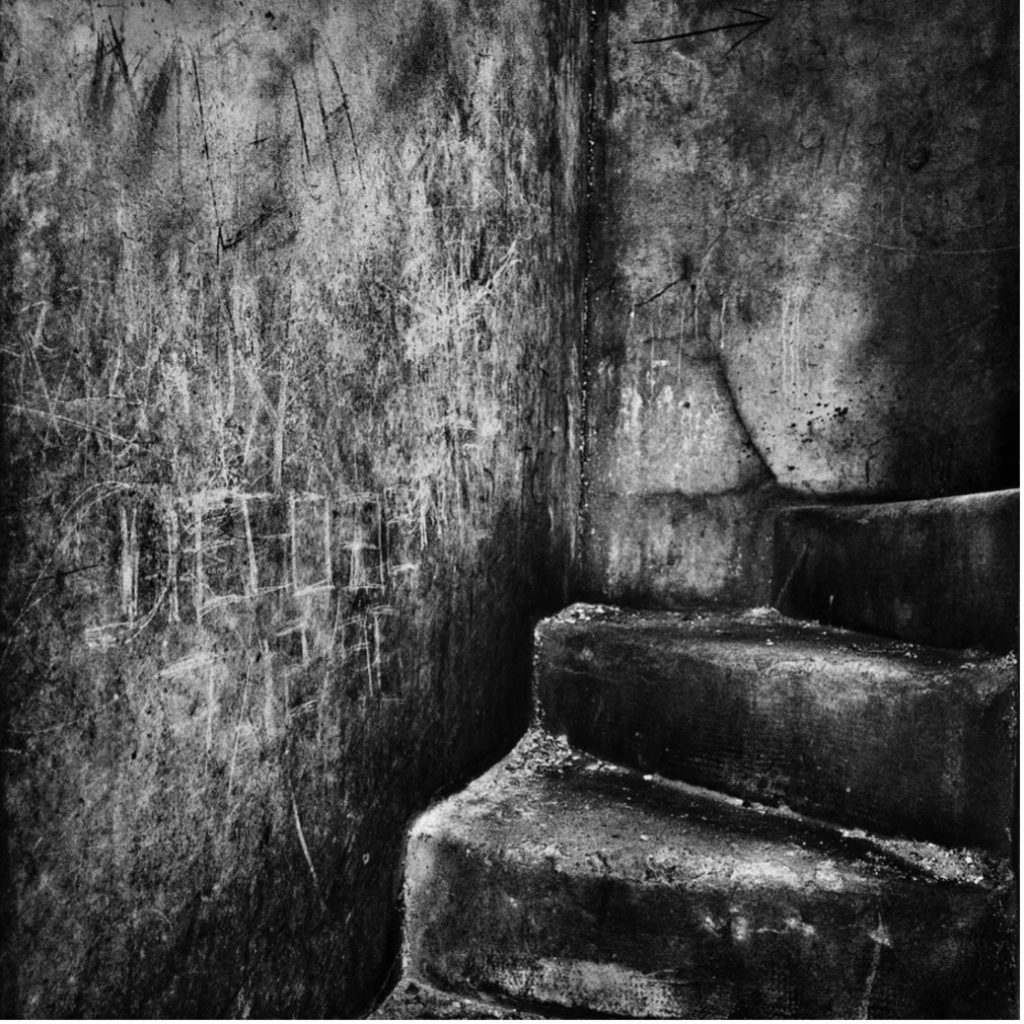

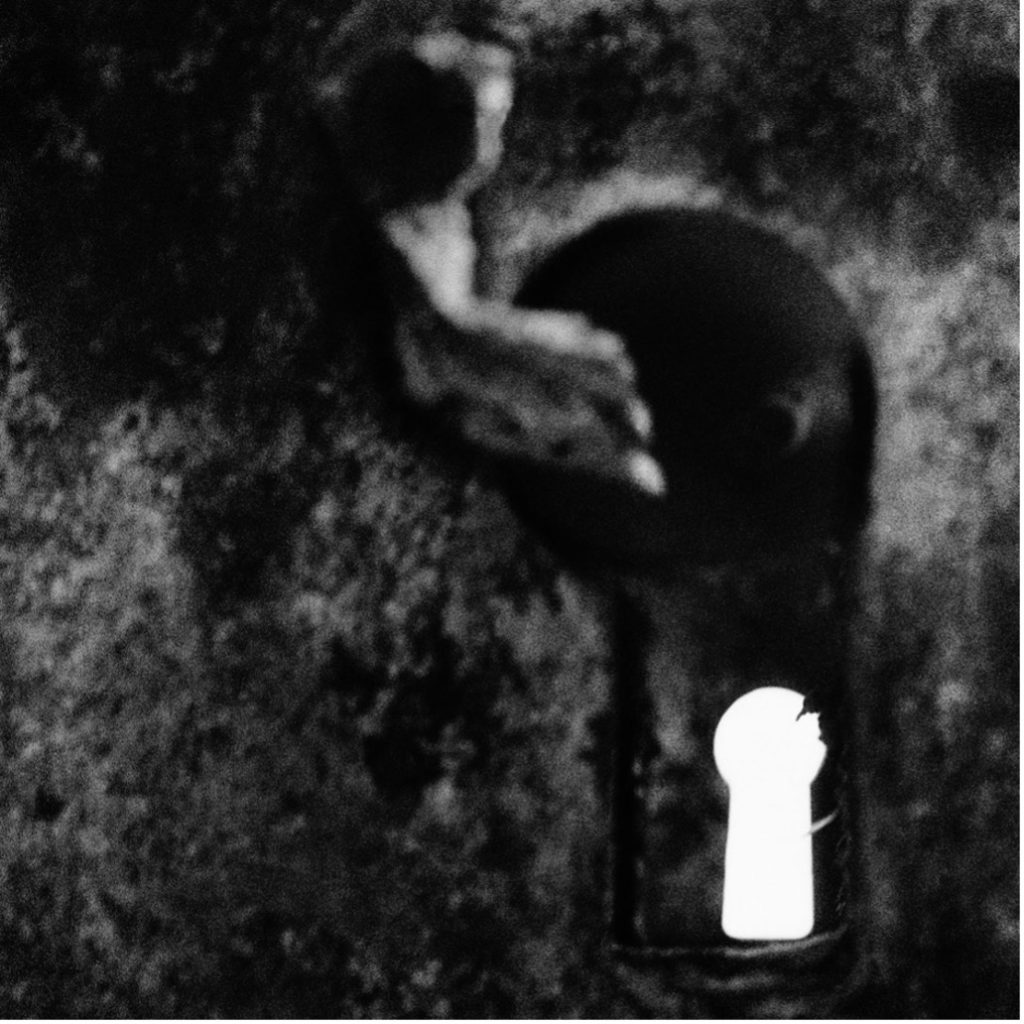

We find fragments of these interviews in El lamento de los muros [The Wailing of the Walls] (2000-2010), Luttringer’s second series, ‘a project by a woman, for women, wholly supported by women’ (Foster 2020). For this work, she interviewed around fifty survivors who do not often talk about their experiences in public. Their testimonies accompany black-and-white images of Clandestine Centres of Detention and Torture, often taken at close range, the camera focusing on details midst unrecognisable backgrounds: a flower growing from between rocky soil, an old football, an impenetrable door with a lock, an unsettling shadow, a stain on a bare wall, an ant escaping from a crevice, and a broken window.

In The Slaughterhouse the cows have no way out, no opportunity to survive the butchery, or to oppose those who will slaughter them. Conversely, though this project speaks of the horror of the detention centres, it also highlights what has not entirely disappeared and speaks of the survivors’ agency. ‘The imprints of subjectivity left on these deteriorated walls that expose the years lapsed almost brutally,’ writes Cecilia Macón, ‘refer to human wills that used to be there; the wills of people who suffered, of the people who tortured, and also of the ones who tried to disguise themselves … behind masks. There is an intention to focus on the agency of those who participated in the events, in their imagination behind such action, in their hidden feelings’ (2017: 99). The focus on the agency and emotions of those trapped by and on those walls, and on the eerie atmosphere that persists at those sites, is evident, for example, in a photograph of a dark and terrifying staircase that also shows illegible inscriptions on the wall (Fig. 3).

Many of the testimonies that accompany the images of The Wailing of the Walls refer to gender violence. We read, for example: ‘There were no cotton pads, no cloth; nothing. They didn’t give you anything. When we had our period we would drip blood, and I’ll never forget how they would drag us out into the corridor and beat our legs with sticks, saying: look how they drip and bleed, just like dogs, like bitches, leaving a trail of blood behind them.’ (Marta Candeloro, abducted on 7 June 1977 in Neuquén and taken to the Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture called ‘La Cueva’). Next to a photograph of a lock promising a world beyond the prison walls (Fig. 4) we also read: ‘I cannot be in closed places. For example, I go to the bathroom, and I have to leave the door open; I can’t tolerate being locked up. I think it has to do with the issue of the hood, the feeling of suffocation and rape … All rape also involves a lot of guilt and also a lot of shame. It is one of the most degrading forms of torture for a woman’ (María Luz Pierola, abducted in Concordia on 25 February 1977 and taken to the Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture known as ‘La Casita de Paracao’). If in this photograph the hole in the door lets some light in, perhaps evoking some hope of being heard or seen, another photograph of a blurry heavy deadlock and no visible openings conjures up secrecy, what remains in the shadows, behind locked doors. We read in the caption next to this image: ‘In my case it [rape] was prior to torture and always by the boss, it was always like that, it was always the leader of the mob. That’s why the greatest difficulties I had to overcome were those to do with sexual relationships … It was really difficult to receive a caress again, to feel it as a caress rather than as groping. With her [another prisoner] it was different, she had a really great figure, and the guards would come and rape her without torturing her. The sensation of repulsion and distress that is produced by having to watch someone being raped at your side is different from other types of torture … They would hit all of us, they used the cattle prod (picana) on all of us, but this situation created a much greater sense of repulsion and distress’ (Beatriz Pfeiffer, abducted in Concordia on February 25, 1977. She was then taken to the Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture known as ‘La Casita de Paracao’). María Luz Pierola and Beatriz Pfeiffer were together when they were kidnapped and they were kept together, chained to each other, in the CCDT. María Luz was eighteen years old and Beatriz nineteen or twenty. During the day, when they were not being tortured, they told each other stories and talked about films as a way to hold on to life.

In a chapter from The Civil Contract of Photography (2008), provocatively entitled ‘Has anyone ever seen a photograph of rape?’ Ariella Azoulay argues that rape is an invisible object, one that often occurs in a private space. She affirms that the great achievement of feminist movements and the sexual revolution has been ‘to remove rape from its sexual context and restructure it as an act of violence,’ and to have constituted ‘the rape victim’s position as one of legitimate grievance’ (220). Azoulay adds that ‘presence before the gaze generates new conditions of speech and makes intervention possible,’ although ‘accessibility to the gaze doesn’t mean that the object is necessarily visible’ (241). In other words, there must be changes in the legal and civilian spheres too, to recognise rape as a state of emergency.

Photographs like Luttringer’s, which evoke and at the same time do not explicitly show sexual violence, are important because fighting in the visual arena ‘is an inseparable part of any struggle in the political arena, for it is in the visual arena, through and by means of images, that women and men train themselves to feel, see, think, judge and act’ (281). Her decision to include testimonies of torture and sexual violence—which in fact never took place in ‘a private space,’ but rather in public buildings converted into Clandestine Centres of Detention, Torture and Extermination—is motivated by an understanding of sexual violence in the context of the dictatorship not as an attack on dignity, personal morality, or ‘private honour,’ but instead as a crime against humanity.

Fading Away

When Luttringer started The Wailing of the Walls in 2000, that view of sexual violence and rape was not common in Argentina. It is only perhaps now, in a cultural climate transformed by feminisms, and following changes in the law regarding sexual crimes during the dictatorship, that the object of these images becomes truly visible to the gaze, that we can really see it. One of the motivations for the The Wailing of the Walls was precisely to give visibility to survivors from different Clandestine Centres spread around the country, not just those located in the capital. In this sense, this project reminds me of the photographs of women that Helen Zout took for her work Disappearances (2000-2006), many of those women survivors of CCDT in Bahía Blanca, La Plata, and the Province of Buenos Aires.

Luttringer and Zout not only share similar aesthetic approaches but also life stories. They met in the 1970s in La Plata and attended the same high school. Zout was in the year below Luttringer, and they were both members of the UES. Zout was also pregnant when she narrowly escaped being kidnapped during the military regime. Between 1983 and 1986 she was a photojournalist for the newspaper La Razón, and between 1990 and 2007 she was a photographer for the Cámara de Senadores of the Provincia de Buenos Aires. She was also the photographer and curator of the Museo de Arte y Memoria de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. She met Luttringer when they were fourteen or fifteen years old, and they saw each other again only twenty-five years later, when they were forty-five and forty-six years old, respectively. ‘Helen,’ says Luttringer, ‘had not changed a bit. She was always very clever. The things that some of us saw many years after the facts, she had already seen them. Her fascinating and imaginary interior world was there even before the dictatorship, and it never changed’ (interview with the author, 6 April 2021). Zout also speaks fondly of Luttringer, with whom, she says, she is united by politics and ‘a life story’ (email 6 May 2021).

Zout’s Disappearances is comprised of black-and-white, nightmarish and out-of-focus images of the traces of the dictatorship’s crimes, of survivors, of the planes used for ‘death flights’ to dispose of victims’ bodies, and of skulls found by forensic anthropologists after the dictatorship.[2] The series also includes photographs taken from a police archive, legal documents that had the double objective of covering the traces of the crime and keeping a record of the killings. There is one photograph taken from this archive that is particularly striking. It shows a perpetrator holding two guns, wearing a suit and a mask. Writer Martín Kohan (2018) highlights the sinister irony of this picture of a repressor who appears here ‘encapuchado’ [hooded], an image that evokes not only the uniform of the Ku Klux Klan, but also the disappeared, who were forced to use hoods while in captivity. However, says Kohan, this mask is not made to prevent the bearer from looking/knowing but to prevent others from recognising him. This photograph also speaks of the patriarchal nature of totalitarian regimes, the macho attitude of torturers, but also their cowardice, as he does not show his face.

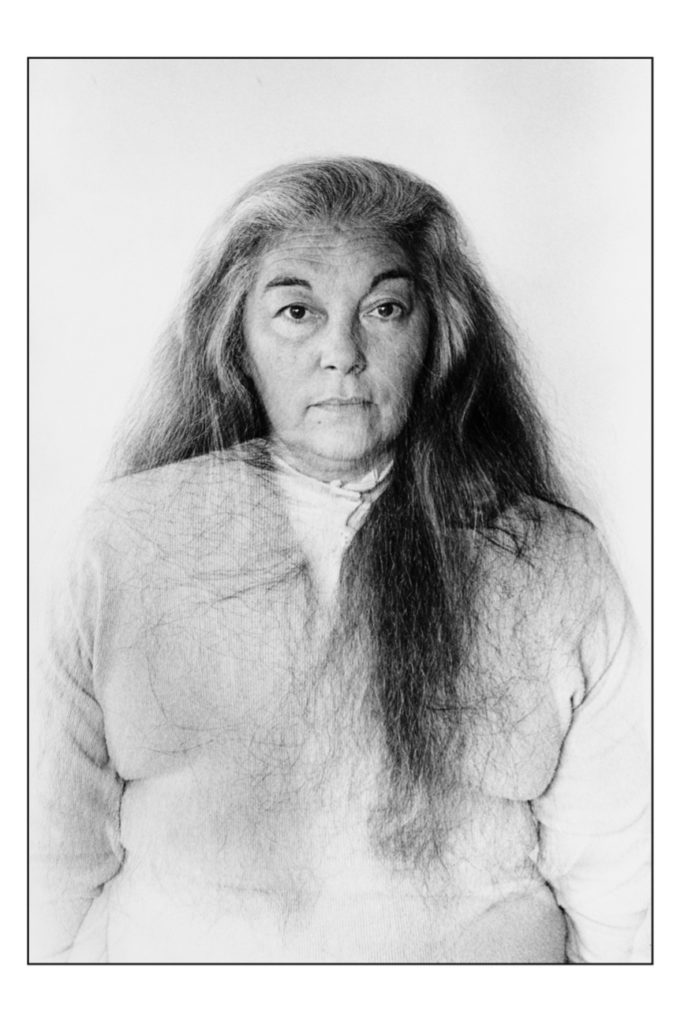

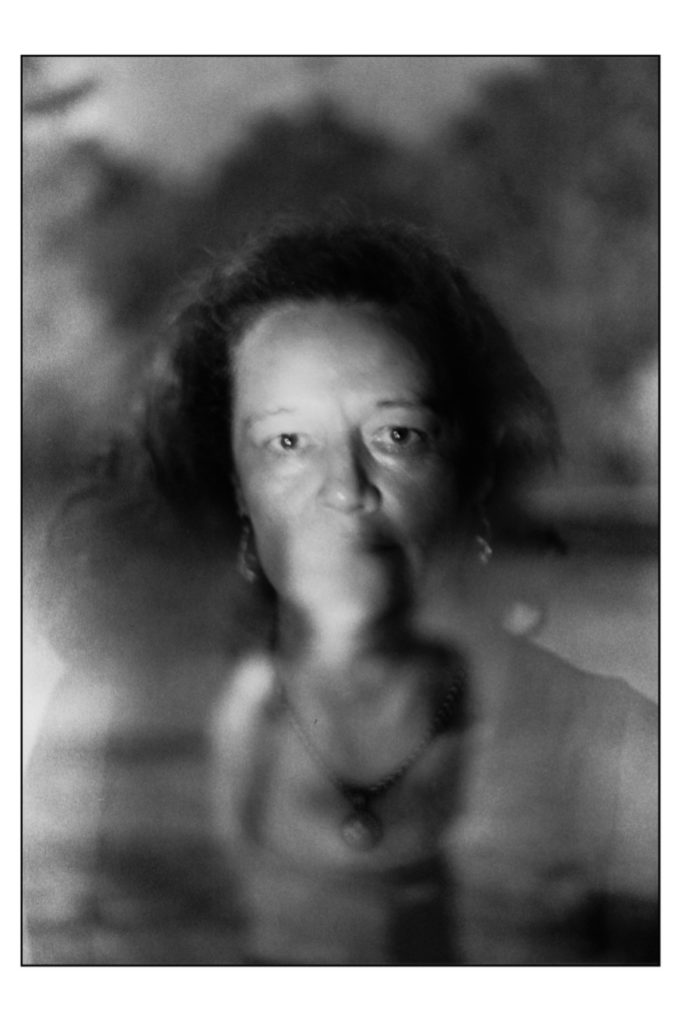

Except for the portraits of Víctor Basterra and Julio López—the latter was disappeared twice, first during the dictatorship and then in 2006 after giving testimony against the perpetrator Miguel Etchecolatz—the survivors in Zout’s series are all women. There is, for example, a photograph of a spectral figure, a survivor of the so-called ‘circuito Camps,’ Nilda Eloy, who looks like an apparition: white, blurry, eternally young, a gothic image of someone who appears to have just been resuscitated (Moreno 2006) (Fig. 5). ‘Nilda has very long and grey hair,’ says Zout, ‘she looks like those people who were stuck in time after a traumatic event’ (cited in Fortuny 2014: 75). The rest of the photographs of the women survivors are equally spectral. In all these pictures, they look otherworldly, like the living dead.

Like Luttringer, Zout uses techniques of double and slow exposure to capture the visual uncertainty of death and the idea of broken spaces and times due to trauma. There is a blurry photograph of Adelina Alaye, mother of Carlos Esteban Alaye, disappeared in 1977, and an equally out-of-focus photograph of Cristina Gioglio, survivor of the Clandestine Centre Arana, taken at a distance, barely recognisable, surrounded by cars piled on top of each other. During her detention-disappearance, Cristina could hear the guards from her cell. They played truco (an Argentine card game) to decide whether to keep her alive or not. She survived, but suffered all manner of torments while acting as cook and slave for her captors.

Luttringer says that in Zout’s photographs the women survivors look like spots or stains: ‘Zout strips the survivors of matter, her photographs are heavily washed. They are like white stains (manchas) as if someone’s spirit had emerged from those white spots. It is a stain that is here but at the same time is not here, because it evokes a disappeared person. Zout has managed to materialise the idea of disappearance in one of the most beautiful ways that I know’ (Interview 6 December 2021). Disappearance and torture have disrupted notions of times and place in all these images, inhabited by doppelgängers, shadows and silhouettes. Here, survivors unfold in pairs, both unable to leave the past behind—a past that in any case has not passed—and also trying to live in the present.

There is one photograph in The Wailing of the Walls that was not taken in a clandestine centre, but Luttringer is not interested in revealing which one (Fortuny 2014). She does not want to lose the uncertainty because, she says, in some ways survivors have never left those walls. In Disappearance, there is a photograph of Patricia Chabat, survivor of the clandestine centre known as La escuelita, in Bahia Blanca, that expresses this experience of fragmented identity (Fig. 6). ‘It was very difficult for me to interview her,’ says Zout, ‘her gaze is very intense. It looks like she is coming from a distance, but at the same time she is very close to the camera. It is as if she had two bodies’ (Interview with the author 14 December). Another photograph captures the blurry outline of another female survivor. In this case there is not even a name to bind together the different selves of the survivor, only identified as: ‘M. survivor.’ Many of the women photographed by Zout died young.

During her interviews with the women survivors, Luttringer also took pictures of them, but she did not include these portraits in The Wailing of the Walls, because ‘to me the focus of that project were always the walls’ (Interview 6 December). Walls also feature in The Slaughterhouse. One of the most powerful pictures in that series is a photograph of a wall of white shiny tiles covered by blood stains. But the walls of the Clandestine Centres that we see in The Wailing of the Walls are not glossy and pristine, but dark and rough, some made of stone or a similar material. As a gemmologist, Luttringer knows how to listen to the mineral memories of these walls. Marks on the walls echo the political slogans graffitied in public spaces during the 1960s and 1970s, and also memorial walls inscribed with the names of the disappeared. These walls become sites of tactile encounter when people touch the engraved letters and somehow feel connected to their loved ones, as happens, for example, in the Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism in Buenos Aires. As a photographer, Luttringer is not only able to listen to the wailing of the walls, she also knows how to make the walls ‘speak.’

Stains on the Wall

In a poignant text that Luttringer wrote for The Wailing of the Walls after winning the Guggenheim Fellowship in 2000—when she was still an amateur photographer but already an expert gemmologist—she wrote that the walls of the Clandestine Centres are covered by strange figures and stains, like the ones often found on precious stones displayed in sixteenth and seventeenth-century curiosity cabinets. These figures and stains were thought to be ‘the result of acts of violence which had taken place to these minerals, in whose immutable substance they left their imprints for all eternity’ (unpublished). Clandestine Centres of Detention and Torture in Argentina made use of existing buildings which were repurposed before being revamped following the collapse of the Military Junta in 1983, or simply neglected. Luttringer wonders: ‘[h]ave those nondescript frontages by which thousands of city dwellers pass daily kept traces of the dreadful events they harboured, as have the imagined stones of display cabinets?’

Luttringer takes chilling photographs of the walls of Argentina’s sites of horror partly to answer that question. Humidity, the passage of time, and decay have produced ghost-like stains on the wall, shadows of human silhouettes that evoke both the terrifying perpetual absence-presence of both the perpetrators and the victims in those places (Fig. 7). Her photographs of surfaces, textures and stains on the walls are true-to-life and abstract at the same time, combining the tradition of ‘straight’ photography, recording the world as the lens ‘sees’ it, and the abstract form. These images evoke not just the stories told by inanimate things—walls, objects, stones- but also the ‘emotions’ and ‘mood’ of material things, their ‘vibrant matter’ (Bennett 2010) and their agency.

‘When I walked the Clandestine Centres the stains on the wall always caught my attention,’ says Luttringer. She adds that during those visits she was always accompanied by a story written by Uruguayan poet Juana de Ibarbourou called The Humidity Stain (1944). In Ibarbourou’s story a young girl is fascinated by a humidity stain on the wall of her bedroom. At night, before falling asleep, the girl makes wonderful discoveries, as she imagines that they look like the Coral Islands, the profile of Bluebeard, and the face of Abraham Lincoln. When her parents ask a painter to cover the stain she feels completely at a loss, longing for her spectral friends and her imaginary universe.

Stains and shadows are expressive, and resist figuration at the same time; an apt quality to evoke both disappearance and the acts of sexual violence described by survivors in The Wailing of the Walls. Luttringer’s third project Cosas desenterradas [Unearthed Things] (2012), also relies on the expressive language of shapes and textures to bear witness to torture and sexual violence during the dictatorship, a crime that poses several challenges to photography and visual discourses more generally.

This series is comprised of photographs of different objects found during excavations undertaken by archaeologists at the former Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture known as ‘Club Atlético,’ active between February and December 1977: a ping pong ball that the perpetrators used to play with while prisoners were being tortured (Fig. 8), a solitary sock, worn away and barely recognisable as such, a fragment of a lightbulb, a shoe decayed by time and humidity (Fig. 9).

Unlike the images of The Wailing of the Walls, the objects here are photographed against a white background, placed in the middle of the image, as if the massacres had wiped out everything, even the walls and floors where the crimes took place. This decision reminds us that this concentration camp was demolished at the beginning of 1978, to allow for the construction of the 25 de Mayo freeway, one of the most ambitious architectural projects of the dictatorship. Now just a plaque, placed under the flyover, refers to the dark past that lurks underneath. These objects are thus the only evidence, the only witnesses, of the crimes. They have lost their utilitarian function and cannot speak, but they are not mute. ‘Objects hold memory,’ says Luttringer, ‘when people see a picture of a sweater, a button, a shoe that had been worn by someone who ‘disappeared’ during the dictatorship, the very style of the object confirms its truth’ (Foster 2020). But objects do not speak for themselves. It is through our interrogation of them, through an archaeological gaze, that they look at us from their hidden times and buried spaces.

Unearthed Things includes a sort of ‘triptych strictly centred on sexual violence’ (Macón 2017: 98), comprised of the images Corpiño (bra), Medibacha en microfilament (Tights in Microfilament), and Cachiporra (Blackjack). These images always carry the risk of attracting a morbid gaze, or of merely shocking the viewer with their graphic content. But Luttringer presents these findings as both pieces of clothing and as shapeless objects at the same time, as figurations and abstractions. The bra is the only object that she photographed more than thirty times. (Fig. 10) She was not allowed to touch the objects, so an archaeologist wearing white gloves assisted her. Luttringer asked her to put the bra (strictly speaking its pieces) on top of a translucent piece of paper like the kind her father, who was an architect, used for his work. She then asked the archaeologist to remove it and to put it on the paper again several times so she could take photographs of the object looking different every time. She wanted the bra to represent different bras, to evoke all the women who had been detained and disappeared in those sites. She wanted to tell the stories of women with different lives and backgrounds: students, workers, cooks, employers, members of the bourgeoisie. ‘It didn’t matter where we came from, what was important was that we were all together, fighting for the same objectives’ (Interview 6 December 2021).

After giving testimony in the 2018 trials, something radically changed for Paula Luttringer. For twenty years she never spoke about what happened to her, not even with her family. During that period, she also showed only a fragment of her work, even though she never stopped taking pictures. She was afraid that public exposure of her images would jeopardise the case against her captors. She was concerned less about what might happen to her than about knowing that her testimony was important for sending those responsible for the disappearance of her friends to jail. When she received exhibition invitations, she would put them in a drawer. Now that the trials have taken place, it is as if a wall has been broken and she has found a way to work with her archives again. The lockdown enforced by the pandemic has helped this process. As a producer of documentaries in France, she travelled a great deal and did not spend more than two or three weeks in the same place. Being at home allowed her to open her archives and discover images taken a long time ago that she is now preparing to exhibit for the first time on a new website.

She is working on a new project/exhibition comprised of three panels. The first will exhibit twenty 8×10-inch photographs with the negatives of the bra found at the Club Atlético. They are uncanny and spectral images: ‘what I like about the negatives,’ she says, ‘is that they look like abstract drawings, you can’t tell that what you are looking is a bra; it looks like a bird, stains or just a shape’ (Interview 6 December). A second panel has nine 9×12-inch photographs of underwear that she has never shown before. She has duplicated the same black-and-white image of the object, but each iteration has a lower grade of shade, as if the object were gradually dematerialising until it almost disappears. A third panel has 27 8×12-inch frames with fragments of conversations between Luttringer and the women survivors (the project is provisionally titled Conversando/Conversing). These panels will be accompanied by an unframed canvas with double-exposed and superimposed portraits of the women.

Luttringer’s formalist eye—her use of extreme close-ups and of light and shadows, her monochromatic images and careful consideration of framing—proposes an approach to the legacies of the dictatorship—physical wounds, objects, sites of horror—that is at the same time documentary and expressive, a gaze that captures both realities and emotions, and sites and atmospheres. This is, in my view, one of the main attributes of her work: she takes pictures of the outside world to let viewers glimpse a tiny portion of the convulsive interior lives of survivors. Those who have not experienced torture will never know what it is like to live day after day, night after night, with the burden of such excruciating memories, of being unable to escape smells or noises that transport survivors to the darkest places and times of their lives. Those memories cannot be shared. But images can.

The Bark of History

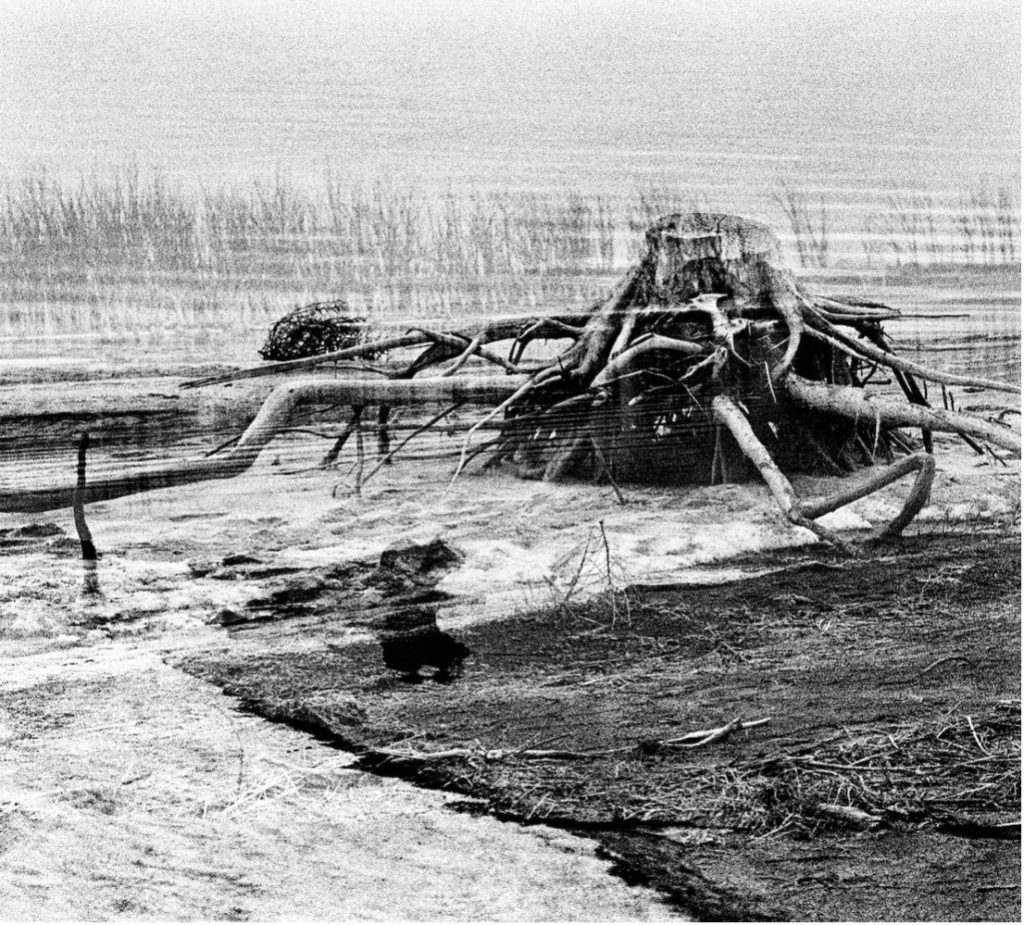

In Lignum Mortuum [Death Wood] and Entrevero [Entanglement] (both from 2015), comprised of photographs of a dead forest, Luttringer puts the links between documentary and imagination into tension even further. The images of these series are eloquent and loud, even when at first sight they seem to say that there is nothing here to see at all, even when they refuse to give any information about the past.

If the focus of her previous projects was the experience of women survivors and the strength of the collective, these two series turn the gaze towards Luttringer’s own inner life, to her own internal struggles. At the same time, the images speak of several collective tragedies: both series explore the devastating consequences of the lack of public policies to protect the infrastructure of small towns during and after the dictatorship. In 1985, after a season of heavy rains, flood water broke through a dam in a salt-lake and inundated a spa town called Villa Epecuén. Within days the whole town disappeared. When shifting weather patterns later led to drought, the remains of the town and all its trees re-emerged, glistening with salt, drying, and bleaching ‘like bones in the sun’ (Luttringer). She travelled to this ghost town to take pictures of its architectural ruins. At the end of the working day, she went into the forest and took pictures of the dead trees. It would be those images, and not those of crumbling infrastructures, that ended up the focus of both series. [3]

Lignum Mortuum is comprised of black-and-white pictures and, as with the images of The Slaughterhouse, it is not clear what time of day they were taken, as everything is presented in a gloomy grey tone. One image is a close-up of an amputated trunk that appears to be lit up from the inside (Fig. 11). Another shows a felled tree. In the background we can see an out-of-focus lake and a lonely and skeletal tree. A third photograph also shows a severed, spiky trunk, its interior comprised of what appears to be a furry texture. The camera angle makes the figure resemble some sort of strange animal, or even a woman lying with her legs open, her intimate parts exposed.

In the photographs of the dead forest of Villa Epecuén, Luttringer looks at the trees, or what is left of them, as if she were interrogating dead witnesses. In a short but evocative book called Bark (2014), Georges Didi-Huberman writes about his disappointment with Auschwitz, a place of barbarism that has now been converted into a place of culture and an exhibition of a theatrical memory. In sharp contrast, he argues, Birkenau has been kept not as a museum, but as an archaeological site. Unlike at Auschwitz, Birkenau requires visitors to interrogate their own gaze. It demands, in other words, imagination and the need to ‘listen’ to the testimonies of the soil, the trees and the walls, what Didi-Huberman calls ‘the bark of history,’ everything that the murderers left behind because they considered these remains too superfluous and too innocent to function as evidence of their crimes.

All these texts and images propose an understanding of memory that shifts from human-centred ideas of transmission to an experience of trauma associated with environmental loss and endangered ecologies. In the case of Luttringer’s images, they mourn the absent bodies of the dictatorship: ‘I can’t deny,’ the photographer says, ‘that when I was walking through that place, I felt a shudder related to my story’ (interview with the author, April 2021). At the same time, they transmit what scholars have recently called an ‘ecological grief’ (Craps 2020). If we tend to associate grief and mourning with human losses, ‘ecological grief’ expands the circle of the grieveable beyond the human. These landscapes are about past and present but also about the future of the planet. At the same time, they are less about documenting the fragility of nature than about revealing something of Luttringer’s interior life. ‘I don’t go to nature to document it but to be part of it. The images that arise when I am in the wild reflect what is inside me at the time’ (interview with the author, April 2021).

‘Survivors of political violence,’ says Luttringer, ‘share some problems in common. We have gaps in our recollection, and sometimes we get unexpected flashes of memory. These flashes are not words but images, mental pictures. We cannot choose when these mental images come to us. We cannot erase the mental pictures that arrive, and we cannot change what they reveal. If we try to shut them out, they insist. The flashes of memory arrive during good moments in our lives, when we are relaxed … They burn in our mind, yet they cannot be shared with anyone else’ (Foster 2020). Photography allows Luttringer to create images that suggest what is on her mind, even though they cannot fully convey the whole dimension of trauma.

‘Accidental’ remembering characterises both The Slaughterhouse and the last series I address here, Entrevero. While Luttringer was photographing the tree trunks of Villa Epecuén, she accidentally put rolls of exposed film into the camera and used them again. When she developed the film in Paris, she realised what she had done, and was furious at the wasted time and material. When she later returned to the film and made a contact sheet, however, she saw different worlds superimposed on each other, haunted landscapes of broken trees and unearthed roots layered on top of each other in similar fashion to layers of memory (Fig. 12). In English, Entrevero translates as ‘entanglement, confusion, disorder,’ an apt term for these double-exposed photographs of twisted branches, roots that grow in queer directions and that look like the arms of some sort of alien creature, and trunks that rise horizontally and contra natura, all creating eerie spaces of superimposed spectral times and anachronisms (Didi-Huberman 2002).

If ‘photography is the art of the return and hence the art of the uncanny’ (Raymond 2019: 8), these images are doubly uncanny. The dying trees emerging from the salty waters point, allegorically, to an ‘unhappy reality that comes to light’ (Raymond 10). But the uncanny in this series does not stop there because that (phantom) reality was only visible to Luttringer after developing her films, on the negatives (she uses an analogue camera). ‘The photographic negative,’ writes Raymond, ‘is the essence of the photographic uncanny in its ability to take what is quotidian and common—a bright sky, a building, and men standing before the building—and make it appear otherworldly’ (12).

I associate the images of Villa Epecuén with Luttringer’s experience of motherhood in captivity, not least because nature (from the Latin word ‘natura,’ meaning ‘birth’) has often been personified as maternal. In Inca mythology the Pachamama (the Earth Mother or Universe Mother) is also a fertility goddess who controls planting and harvesting. There is something about a forest that is almost dried out, but still resists disappearance that speaks to the fact that Luttringer is one of the few women who gave birth in captivity and survived the dictatorship with her daughter. When she was forced to leave the Clandestine Centre, she could not bear the thought of leaving her friends and compañeros behind. Before leaving, the disappeared filmmaker Pablo Szir, who had helped her to look after her baby, hugged her, whispering that she had to leave that hell and tell the world what was happening there. Photography became her way to speak not so much about her traumatic experiences, but rather about the difficulty of speaking about them afterwards, and of bearing witness in spite of all.

Final Words

In The Unwomanly Face of War, originally published in 1985, Svetlana Alexievich writes: ‘[w]hen women speak … [their] stories are different and about different things. ‘Women’s’ war has its own colours, its own smells, its own lighting, and its own range of feelings. Its own words. There are no heroes and incredible feats, there are simply people who are busy doing inhumanly human things. And it is not only they (people!) who suffer, but the earth, the birds, the trees. All that lives on earth with us. They suffer without words, which is still more frightening’ (2017: xiv). In the testimonies of women survivors of the Rwandan genocide, gathered by Jean Hatzfeld in Life Laid Bare (2000), the women recall how the Hutus massacred the Tutsis alongside cows, the victims trying to hide from the killers as best they could in swamps and bushes, keeping quiet like ‘fish in ponds’ (83). When the women recall the horrors of the genocide, how they were cut with machetes and how they witnessed their loved ones perish, they often use images taken from nature to talk about those painful memories and their lives today. ‘I think that from now on a gulf in understanding will lie between those who lay down in the marshes and those who never did. Between you and me, for example’ (40), says one of the victims. ‘I see only obstacles in my life, marshlands around my memories, and the hoe reaching its handle out to me’ (85), says another woman. Similarly, Luttringer says that sometimes, when she tries to remember something about those years, it is as if her memories were covered in a mist or haze. In all these accounts, nature suffers, and at the same time offers survivors images that help them break the wall of silence and narrow that ‘gulf,’ that ‘marshland,’ that separates them from those who have not suffered similar things, even though that gap can never be entirely removed.

In Luttringer’s work both human and more-than-human, people and animals, trees, and stones, are all ‘grieveable,’ all worth mourning. Her photographs tell the stories of survivors, of ‘people who are busy doing inhumanly human things’ and also remind us of the expressive power of photography and abstraction, perhaps because disappearance confronts us with the terrifying experience of ‘losing the human form.’ [4] It takes an attentive and compassionate eye, and a skilful artist, to see a person—a mother, a daughter, a militant, a friend—where others can only see desperate beasts, pieces of clothing, dried wood, or a stain on the wall.

Notes:

[1] One example of this change of paradigm was the exhibit Mujeres en la ESMA: Testimonios para volver a mirar [Women in the ESMA: Testimonies to Look Again], inaugurated in 2019 at the ex-ESMA, the former Navy School of Mechanics that functioned as a Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture (CCDT) during the dictatorship, and which has been now converted into a Museum and Site of Memory. The exhibition is based on survivors’ court testimonies about violence against women and sexual crimes committed by the ESMA Task Force. Their website states that ‘[s]et in dialogue with the new sensibilities awakened by the women’s movement today and their street demonstrations, the exhibition takes a new look at the functioning of the clandestine centre ESMA through a gendered perspective, an aspect that to date has been absent in the Museum’s permanent exhibition’ (museositioesma.gob.ar). One of the most interesting aspects of the exhibition is indeed its self-reflexive approach towards its own curatorial narratives. This self-reflection is expressed in the use of a gendered perspective to revise and correct the language originally used to describe what happened in that site of horror. For example, the word ‘torturados’ has been highlighted with a red pen and the word ‘torturadas’ has been inscribed in handwriting next to it. Moreover, Women in the ESMA offers a transgenerational perspective on recent Argentine history, picking up ideas and slogans used by contemporary women’s movements, such as the notion of sisterhood or the phrase ‘We Want to be Alive,’ to refer to both the violence suffered by women at the ESMA and their strategies of survival and resistance. For more about this Clandestine Centre of Detention and Torture from the perspective of women survivors see Ese infierno: Conversaciones de mujeres sobrevivientes de la ESMA (2001).

[2] See www.helenzout.com.ar (last accessed 14 June 2022).

[3] See Blejmar 2021 for a more detailed analysis of this work.

[4] Losing the Human Form is the title of a 2013 exhibition on Latin American art, politics, and memory from the 1980s inaugurated at the Museo Reina Sofia.

REFERENCES

Actis, Munú et al. (2001), Ese infierno: Conversaciones de cinco mujeres sobrevivientes de la ESMA, Buenos Aires: Altamira.

Azoulay, Ariella (2008), The Civil Contract of Photography, New York: Zone.

Bennett, Jane (2010), Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Durham and London, Duke University Press.

Blejmar, Jordana (2018), ‘Reses, sombras, siluetas: Sobre El matadero de Paula Luttringer’, in Gabriel Gatti y Kirsten Mahlke (eds), Sangre y filiación en los relatos del dolor, Madrid: Iberoamericana, pp. 209-220.

Blejmar, Jordana (2021), ‘La corteza de la historia en las imágenes espectrales de Paula Luttringer’, Revista Atlas, 21 June 2021, https://atlasiv.com/2021/06/21/la-corteza-de-la-historia-en-las-imagenes-espectrales-de-paula-luttringer/ (last accessed 18 February 2022).

Craps, Stef (2020), ‘Introduction : Ecological Grief´, Special Issue Ecological Grief of American Imago, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp. 1-7.

Didi-Huberman, Georges (2002), Survival of the Fireflies, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Didi-Huberman, Georges (2014), Bark, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Filc, Judith (1997) Entre el parentesco y la política: Familia y dictadura 1976-1983, Buenos Aires: Biblios.

Fortuny, Natalia (2014), Memorias fotográficas: Imagen y dictadura en la fotografía argentina contemporánea, Buenos Aires: La Luminosa.

Foster, Alasdair (2020), ‘Paula Luttringer: A Keeper of Memories’, Taking Pictures, 7 March 2020, https://talking-pictures.net.au/2020/03/07/paula-luttringer-a-keeper-of-memories/ (last accessed 18 February 2022).

Hatzfeld, Jean (2000), Life Laid Bare: The Survivors in Rwanda Speak, New York, Other Press.

Jelin, Elizabeth (2006), Pan y afectos: la transformación de las familias, Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Jelin, Elizabeth (2012), ‘Sexual Abuse as a Crime against Humanity and the Right to Privacy’, Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 343-350.

Kohan, Martín (2018), ‘Huellas de desapariciones: las fotos de Helen Zout’. In Jordana Blejmar, Mariana Eva Perez and Silvana Mandolessi, El pasado inasequible: desaparecidos, hijos y combatientes en el arte y la literatura del nuevo milenio, Buenos Aires, Eudeba, pp. 71-88.

Macón, Cecilia (2017), Sexual Violence in the Argentinean Crimes Against Humanity Trials: Rethinking Victimhood, London: Lexington Books.

Moreno, María (2006), ‘Sombras’, Radar Pagina/12, 19 March 2006, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-2877-2006-03-19.html (last accessed 18 February 2022).

Raymond, Claire (2019), The Photographic Uncanny: Photography, Homelessness, and Homesickness, London: Palgrave.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey