Intimacy & Play as Resistance: Reimagining Black Female Representation in the Photographs of Noncedo Charmaine

by: Deneesher Pather , June 25, 2022

by: Deneesher Pather , June 25, 2022

This article reflects on the photographs of contemporary South African artist, Noncedo Charmaine, whose works explore authenticity and beauty through intimate photographs of Black female and non-binary bodies. With play and connection as her guidelines, Charmaine’s portfolio reimagines depictions of Black female and non-binary bodies in diverse ways that celebrate their agency and individuality. [1] As an artist creating an alternative South African art archive, Charmaine’s photographs renew narratives of Black female bodies through an awareness of iconographical precedents and body politics.

As shown in her set of promotional photographs for Jamaican-Canadian artist d’bi Young’s Gendah Bendah (2011) music video, and her It has lived as Warriors (2018-2019) series, Charmaine’s photographs widen the breadth of Black female and non-binary representation through the inclusion of diverse body types, states of dress, and environments. [2] Using Charmaine’s own descriptions of her work obtained through personal interviews and e-mail correspondence with the artist, this article analyses Charmaine’s works as necessary inclusive, eclectic and, ultimately, empowered inclusions to the South African photographic archive. Read as playful and multidimensional portrayals of Black female and non-binary bodies photographed by a Black woman, Charmaine’s images of Black female bodies are necessary examples of the ‘oppositional gaze’ and ‘mirrored’ images that resist the harmful stereotypes that have plagued representations of Black female bodies in popular culture, art history, colonial, and apartheid-era photography.

Photography in South Africa has played a crucial role in navigating the country’s complex relationship with race, gender, and sexuality. Andrew Van Der Vlies has described South African public culture as ‘saturated with “affects associated with trauma”’ (2012: 95-96), where art continually engages with collective memory, notions of tradition, community, as well as personal and public identity. In a nation fraught with xenophobia, gender-based and homophobic violence, the art realm grants women, people of colour, LGBTQ+ and non-binary individuals a space to reflect on traumatic events with a sense of agency restricted to them in ordinary circumstances. [3] Zanele Muholi, Sethembile Msezane and Nandipha Mntambo are among a generation of South African visual artists who have, since the country’s transition to democracy in 1994, encouraged conversations about Black representation, decolonisation, gender, and sexual identity through photography. In their art, the body functions as a focal point to encourage re-imaginations of previously and contemporarily disenfranchised identities.

Like Muholi, Msezane and Mntambo, Charmaine’s photography shows a sensitivity to the cultural and political tensions that colour readings of marginalised bodies. In her words, her photographic ethos is concerned with ‘how we change that for the person that finds themselves in that block of the other’ (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November). The ‘other’ and descriptions of ‘otherness’ are employed to describe historically disenfranchised identities, to critique lingering colonial constructs in media and to challenge descriptions of bodies that reproduce racist, sexist, and homophobic stereotypes (Biscombe et al 2017; Farber 2010; Sey 2010; Sonnekus & van Eeden 2009). [4] For Charmaine, identities which fall under the category of the ‘other’ are those with features that have been historically—and that are presently—disavowed by western standards of acceptability. Her art, she states, advocates for ‘queerness,’ ‘authenticity,’ ‘love,’ and ‘beauty’ by showcasing people of colour, particularly Black female bodies, and Black women, in states and spaces that connote freedom from societal limitations, as well as racial and gender tropes (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November).

Exploring the Diversity of the Female Form: Charmaine’s Photographs of d’bi Young

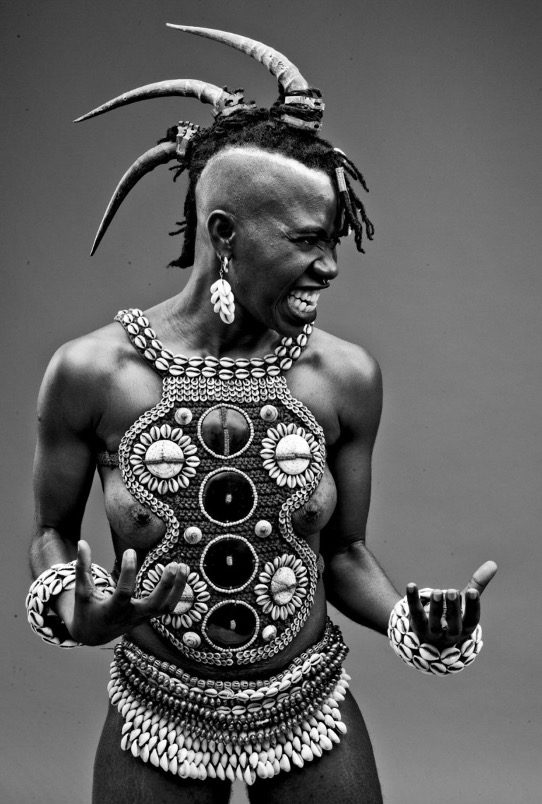

I came across Charmaine’s work on Between 10 and 5, a digital publishing platform that curates South African creative works and showcases artists. In a listicle showcasing twenty emerging Black womxn photographers (see Smith 2017), Charmaine’s arresting image of musician and poet d’bi Young (Figure 1) stood out to me as both fascinating and subversive.

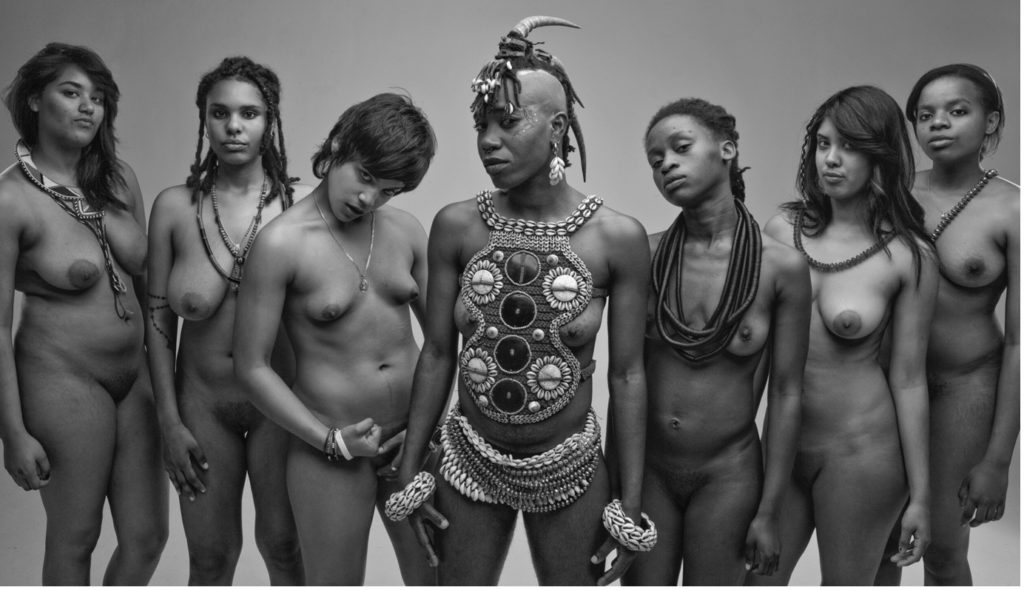

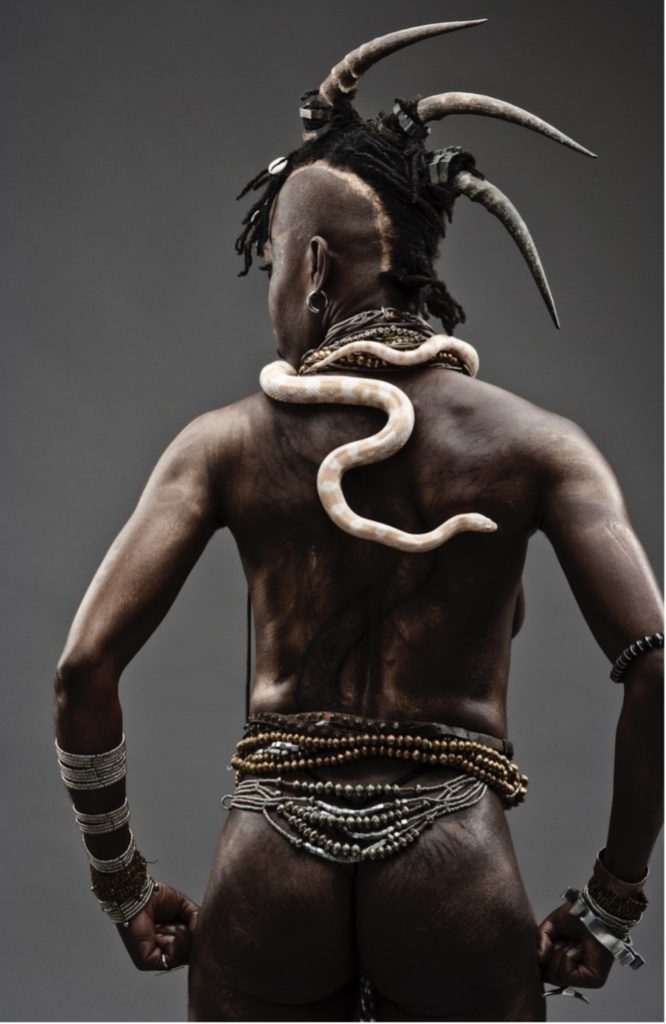

The photograph, I learned later, forms part of a series of promotional images from Young’s Gendah Bendah (2011) music video for their album, 333. [5] Gendah Bendah was filmed in Cape Town with a South African creative team assisting with co-direction, music production, cinematography, marketing, and costume design. As such, there is a prominent Southern African influence in the video’s creative process seen through allusions to Southern African traditional healing, and showcased by Young’s ritualistic dance movements, the use of smoke, ball pythons, and an elephant tusk as props. The creative team also feature as participants in the promotional photography and videography, including a series of photographs that depict Young and the female crew members posing nude and semi-nude adorned with African indigenous jewellery (Figure 2). Gendah Bendah’s lyrics resonate with current issues in South Africa’s social context, particularly Young’s commentary on undoing colonialism, the transcending of traditional gender roles, and the policing of female sexuality:

if yuh passive an meek yuh more female-ful /and if yuh black-work-inna-di-fields-fi-500 years slave-oomaan strong and assertive

yuh not beautiful / yuh look like a man / betta still an afrikan

to all my people who be fucking with genda lines. dissecting race/class/sexual orientation

what’s expected. the status quo. the institutionalized shit [6]

The political messages of Gendah Bendah are clearly expressed in all the photographs from the series. In Figure 1, Young is mostly naked except for a West African-inspired breastplate and strikes a power pose, flexes their muscles, and grits their teeth. Their braids are wrapped in spikes emerging like a crown from their head. Their body is heavily decorated with beads and cowrie shells, the latter being a symbol of wealth, fertility, and spirituality in many West African cultures (Odunbaku 2012: 235). In another photograph from the series (Figure 3), a ball python is draped around Young’s neck and back, while their hands are clenched, directed towards the viewer. In both photographs, their nakedness, in combination with the traditionally masculine stance they assume, communicates an embrace of both masculine and feminine energies. The presence of the snake and the statuesque quality of Young’s body connote a sense of power and divinity. Viewed in tandem with the lyrics and the video, the photographs communicate not only a resistance against the ‘passivity’ associated with traditional notions of the female form, but also a celebration of Pan-Africanism and the African design elements seen in the sartorial choices.

Struck by the photograph, in November 2020 I reached out to Charmaine with a request to interview her about her work. We met at an eatery in Victoria Yards in Johannesburg. When I arrived, she introduced me to her twin and fellow photographer Nonzuzo Gxekwa, and informed me that she was in Johannesburg to visit her family. I explained how I had found her work and that I planned to write about it for this special issue on photography and resistance. She expressed to me that she felt a bit uncomfortable with the formality of academic language. While she saw the language of academia as only comprehensible to a few, she saw photography as a democratic medium accessible to anyone. On whether she saw her own photography as a form of resistance, she said the following:

In a way, yes. Because I guess beauty is at the core of my photography. You see, in terms of aesthetics, people’s looks are just beautiful. But then, beauty is (also) subjective. But we also have a general view of beauty. So, in a way, I find that the things that I capture oppose the standard way of (viewing) beauty (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November).

She further expressed that her photographs are not only intended for those who have expert understanding about their formal properties. Rather, her intended audience is those whose beauty or worth has been overlooked, or even denigrated, by western normative standards.

Although Charmaine’s photographs of Young were in service to the promotion of the music video, the framing of the photographs relay sensitivity to the typical presentation of Black female bodies in popular culture. Charmaine (2021, personal communication, 12 October) stressed that she was wary of reproducing tropes of femininity in her work and was more concerned with capturing the individuality of Young with camaraderie and connection, stating, ‘I had been around females’ bodies that were “soft and feminine,” and here was a body that was not that. It became important that we capture this in a way that was not othering. In a way that was strong, in your face, and powerful.’

As Rana A. Emerson (2002: 122-123) has shown, music videos that feature Black women have tended to favour light-skinned, thin, young, and hyper-sexualised women. Despite their sexualisation, Emerson also demonstrates that music videos have served as a place for subversions of stereotypes about Black women (2002: 126,133). While many music videos portray Black women as being excessively sexualised, there is a rebellion against tropes with visual motifs that imply a sense of ‘agency,’ ‘independence,’ and ‘glamour’ through ownership of that sexuality. In a similar vein, Murali Balaji demonstrates that Black female artists are usually aware of their sexualisation and commodification in media spaces but can manoeuvre their own representation so that there is a better degree of what she refers to as ‘self-definition’ (2010: 17-18).

Though Figure 3 shows Young’s bare back and buttocks, the depiction suggests a resistance against appearing desirable to a white, heteronormative ‘male gaze,’ implied through the presentation of Young’s back as opposed to their front, the inclusion of metallic accessories, as well as through the addition of traditionally masculine signifiers such as spikes and snakes (Mulvey 1975: 13-14). In her editing of the photograph, Charmaine does little to brighten Young’s body. The little direct light in the image highlights Young’s head, tattoos, shoulder muscles, and the python wrapped around their neck. Instead of a commercialised image produced solely in service to promoting the video, the photograph suggests a collaboration in part between Charmaine and Young where the representation of the musician’s body is constructed on their own terms. Read as a photograph of a Black non-binary body taken by a Black female photographer, Charmaine’s photograph of Young could be seen as a manifestation of the ‘oppositional gaze,’ as posited by bell hooks (1992: 116). As the complex relations of Black women as spectators have typically been left out of white feminist literature on spectatorship, hooks’ (1992: 122-129) concept of the oppositional gaze refers to the unique outlook that Black female creatives adopt when imagining radical spaces of inclusion for Black women, and by extension, non-binary, and queer identities.

While the ‘oppositional gaze’ pertains to the representation and spectatorship of Black female bodies in film, Charmaine’s photograph of Young is in line with hooks’ (1992: 123) proposal for Black female ‘critical interventions,’ advocating for empowered and nuanced depictions of Black female (and non-binary) bodies. Charmaine (2021, personal communication, 21 October) expressed that it was important to her that she captured Young with their ‘comfort’ in mind, stating:

As a female photographer, I am learning things about myself first as a woman then as a photographer. The things that I have been exposed to, that influence my image making process and the images I produce. That image making is collaborative, it is important to have a conversation with the people involved. Be clear about your intention. Always check in if the person is comfortable.

As further suggested by hooks (1992: 130), the participation of the ’shared gaze’ among Black females is also imperative to the creation of empowered representations of Black females, and in the case of Charmaine’s images, non-binary individuals. Hooks (1992: 129) refers to the ‘direct unmediated gaze of recognition’ between Black females that negates the traumatic, othering gaze that has visualised spectatorship of Black female bodies in the past. Instead of objectification, the shared gaze reinforces the assertions of personhood between Black females through visualised affirmations of multiple ways of being. Young’s performative assertions of queered gender norms are, thus, reified through Charmaine’s lens. The shared gaze is additionally shown in Figure 2 where Young is seen surrounded by a group of women of colour. Viewing the photograph, the spectator is invited to look openly at the women and non-binary person pictured. The individuals are all naked, except for embellishments of mostly African-style necklaces; one woman flexes her muscles, akin to Young’s pose in Figure 1.

Again, in Figure 2, despite the nakedness of the women, there is a refusal of outright objectification as implied through their challenging stares. The editing of the photograph is minimal, and the women’s pubic hair, stretch marks, and skin dimples remain. Some of the women pictured also feature as extras in Gendah Bendah, with the video’s director, Wisaal Abrahams, standing to Young’s right, implying solidarity with Young and the women in the image. Interestingly, the music video itself does not feature any nudity, and the message of challenging gender roles is communicated through the actors interacting with male and female pictograms, through dance, and performative gesticulation. The disparity between the use of nudity in the photographs and its absence in the video is likely due to the restrictive policies on nudity on YouTube and Vimeo, which limit the audience reach. Where the video takes on a ‘softer’ approach to critiquing gender roles, the use of nudity and posing in Charmaine’s photographs express a more nuanced commentary on the spectatorship of female nudity, the range of female body types, and queering western normative ways of framing female, feminine, and non-binary bodies.

As both a commercial photographer and an artist, Charmaine’s approach to photographing bodies has not always been met with acceptance in the commercial realm. Charmaine expressed that she has experienced backlash in her attempts to photograph the naked or semi-naked female form. She recounted an experience she had with a male magazine editor when she was asked to produce photographs for a women’s month issue:

the pictures I submitted were of women, most of them were like, half-naked. And then the guy said to me, ‘This is not acceptable because it’s in the nude,’ And I said, ‘What about a woman in the nude? You know, we have images of guys (half-naked) and we consume them and it’s not a problem (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November).

Charmaine spoke about balancing the truth in her own approach, and fulfilling the expectations of her clients. She interpreted the editor’s refusal to publish the images of half-nude women for women’s month as implying that women cannot be celebrated if they do not conform to societally acceptable standards of female beauty. In her method, Charmaine makes a conscious effort to ‘celebrate’ the elements of herself, such as her race and her own nakedness, that have previously been interpreted as unworthy of visibility:

[b]ut there’s all these things, there’s so much about being Black that first and foremost, I think for me, it’s like seeing myself. It’s like saying ‘I’m worthy to be seen.’ It’s just celebrating ourselves before even going beyond home, you know what I mean? Because [for] so long, our sense of self has been warped and has been so influenced by other people. That’s what happens when you start to celebrate how your hair [looks], how you dress, how I choose to be tattooed, then everyone else is like, mmm, are you sure? (ibid).

Water as a Site of Healing in It Has Lived as Warriors (2018-2019)

Charmaine’s body-positive sentiments are echoed in another series of photographs, It has lived as Warriors (2018-2019) that includes images of Black women, including Charmaine’s sister Nonzuzo, submerged in a bathtub (Figure 4) and in the ocean (Figure 5). Journalist and cultural commentator Shaelyn Stout (2020) has written about the lack of images of Black women in water in global visual culture as indicative of an erasure of Black participation in public life:

[t]he lack of representation of Black people, specifically Black women, in water is inherent to negative historical connotations and stereotypes of Black relationships with water and swimming. Assumptions that ‘Black people can’t swim,’ for example, are rooted in years of legal segregation, systemic inequalities and the social and financial exclusivity of swimming spaces and education for Black and low-income individuals.

Stout (2020) further posits that the creation of visuals that celebrate the ‘joy’ and ‘freedom’ of water offsets the iconography of Black women as victims of traumatic situations, such as colonialism and apartheid. In Figures 3 and 4, the women depicted look blissful, with their eyes shut and their bodies supine. Although the women are mostly naked, the focal point of the photographs is arguably the beauty of the female forms against the textured surfaces of water. Here, Lynda Nead’s envisioning of a feminine ‘utopia’ is connoted with Charmaine’s intimate images of the women floating freely, naked and unfettered by the stares or limitations placed on their bodies by others. Janell Hobson (2003: 89, 100) maintains that body-positive portrayals of and by Black women are often salves to what she calls ‘unmirrored’ reductions of Black female figures that have reduced Black women to one-dimensional tropes.

Hobson uses Sander L. Gilman’s (1985) analysis of Black female iconography from nineteenth century Europe to show how Black female bodies, particularly Southern African Black female bodies—namely through their genitals and buttocks—were repeatedly associated with disease, decline, and overt sexuality in the medicinal and scientific realms. Consequently, images of Black females became icons in European intellectual spheres, including aesthetics, to signify the degradation of civilised life. Hobson (2003: 96) implies the creation of a semiotic chain where certain negative associations, such as aberration and lasciviousness, ‘stick,’ to use Sarah Ahmed’s (2004) term, negative associations to Black female bodies. To offset the destruction of ‘unmirrored’ images, Hobson advocates for the creation of ‘mirrored’ images which she states reclaim Black female ‘subjectivity’ and ‘agency’ (2003: 98). Mirrored images reinsert Black women positively into the aesthetic realm because they are manifestations of how Black women see themselves. Read as mirrored images, Charmaine’s photographs of women in water have a nearly baptismal quality to them, signalling a release from the old and a movement toward renewed states.

That is not to say that all bodies of water carry positive connotations. The ocean, for example, could be read as a distressing site for Black bodies considering the trauma of the transatlantic slave trade. Rinaldo Walcott (2018: 59-60) positions the turbulent voyage through the Middle Passage as the point of ‘rupture’ for Black slaves which, as he describes, made ‘Black people the symbols and symptoms of an emergent modernity.’ The ocean is thus positioned by Walcott as the locus of the global Black displacement, where a significant part of Black culture and history was lost due to loss of life and lack of material memory. Because of the inability of Black individuals to mourn their dead during the journey, Walcott labels it a ‘horrific psychic crisis,’ exacerbated by the absence of records of lived experiences of the event by Black individuals (2018: 60).

In South African history, beaches carry additional traumatic associations as whites-only exclusionary spaces, where the best spots were reserved for the European population. However, as Meg Samuelson shows, Black people’s enjoyment of the beach, and particularly the photographing of such moments by apartheid-era photographers such as Bob Gosani and Cedric Nunn, also established the beach as a place for Black liberation, defiance and ultimately, freedom (2014: 310). Samuelson, inspired by the works of Peter Abrahams and Lewis Nkosi, writes of the ‘beach-as-threshold,’ and repositions post-democratic narratives of the beach as spaces of potentiality where past racial suffering cannot be erased, yet can be challenged via revitalized connotations. [7] Charmaine holds a similar view to Samuelson in her conception of water as a liminal space with the potential for revival:

My images of women (in water) are about power, freedom. The freedom of individualism in their bodies, in their expression be it movement, nudity, tattoos. I find myself being drawn to water as it is the first space we encounter. We are housed there for the first 9 months of our lives. The first place where dreams and imaginings and life we experience. For me water is a place of remembering, of healing and of newness. (2021, personal communication, 21 October)

Water, for Charmaine, possesses power as a place of rebirth, but her mention of ‘healing’ also speaks to the need for curative imagery for and of Black women in water. With her reference to her subjects as ‘Warriors,’ Charmaine hints at the potency in multiplying the range of Black female representation, as well as the courage that it takes for her subjects to resist societal norms on acceptable nudity. However, as much as Charmaine’s work speaks critically in relation to the legacy of Black female iconography which has limited the full range of Black feminine representation, Charmaine emphasised to me that her approach is more playful than a serious pursuit:

I’m about play, and exploring, and not taking themselves too serious[ly]. But knowing that whatever that they experience in my work is deep, you know? Some of it is really like, even with the people I collaborate with, when we collaborate, there’s a sense of play that is involved. Because like, okay, this is you know a moment where we can let go of whatever, walls, or masks that you’re wearing and just be, you know? And hopefully in that experience you discover something about yourself as much as I the photographer am discovering about myself. But also, the world, you know? Through that little encounter (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November).

In her conversation with Sarah Nuttall, South African artist Penny Siopis (2010: 460), speaks about a generation of young artists who use ‘play’ in their art approach to tackle well-worn topics in the South African context, such as post-apartheid reconciliation, sex, sexism, and racism. She stipulates that although these artists challenge serious subjects, seriousness is not at the centre of their art. Rather, they reimagine how to engage with topics that have no easy answers or ends. Siopsis states that by doing so, the artists can free themselves and their work from the constraints of politicised lexicons (Nuttall 2010: 461). Charmaine refers to her art as ‘play,’ while an artist such as Muholi positions their work exclusively as ‘activism,’ despite including playful elements such as props and costumes (Abel-Hirsch 2020). While Muholi, as an advocate for the LGBTQ+ community, has focused on photographing and telling the individual tales of the participants in their work, Charmaine taps into the ‘sameness’ of Black female experiences by addressing and challenging the categories which Black females have been placed. Charmaine’s reluctance to label her work as activism potentially signifies a resistance to re-creating stereotypical representations of Black female bodies through her own work.

Figure 4 shows her sister, Nonzuzo, in a vulnerable state, naked and submerged in a bathtub, the intimacy of the photograph offset by the red wig and red tinge to the water. The picture, according to Charmaine and Nonzuzo, speaks to the intimacy of sisterhood, and the family rituals that occur behind closed doors:

And for me, I think it was more, it was seeing or remembering in our life we had someone who was free with their body and comfortable. And somewhere along the way it was lost because of all the influences and the things that we see out there. And it’s like how do we reclaim that space and start having these rituals for yourself? And your sisters? Or your friends? (Charmaine, N. 2020, personal communication, 7 November)

Referring to herself as an ‘advocate for humanness’ and ‘humans in their varied states,’ Charmaine uses her photographs to show that beauty is not restricted to certain bodies, races, or identities, but is present in all humans, whether that is acknowledged by mainstream media or not. This is an important intervention in the aftermath of apartheid and the dehumanisation of Black lives.

The resistance in Charmaine’s work is felt in her authentication of elements or circumstances otherwise disregarded. Through her photographs, she celebrates the beauty of Black women and non-binary individuals by showing them in states filled with joy, freedom, and power. Her photographic praxis reflects a sensitivity to the inner world of the subjects she captures, choosing to showcase their beauty and strength which she puts forth as points of connection for her audiences. Charmaine rejects the lens as an objectifying instrument, rather, her work creates examples of mirrored images of Black female and non-binary bodies and Black women that not only queer western heteronormative ways of looking, but advocate for the multidimensionality of all their states of being. In a country burdened with the weight of a violent past, and currently plagued with social and economic inequality, discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community, and gender inequality, Charmaine’s works are valuable reminders of how one can advocate for a transformed yet more equal future through figurations of the body. Her approach is not to minimise difference, but to work toward an inclusive aesthetic that advocates for the right for Black women and non-binary individuals to be seen and appreciated in all their states.

Acknowledgements:

This article would not have been possible without the contributions of my PhD supervisor Professor Amanda du Preez, my senior colleague Professor Lize Kriel, and the financial assistance of the Andrew Mellon Foundation.

Notes:

[1] The terms ‘female’ and ‘women’ are used interchangeably throughout this article but are not intended as exclusionary towards transgender women. Further, assumptions about the gender pronouns of some of the subjects analysed are made purely from the evidence of the photographs.

[2] d’bi Young identifies as non-binary and uses they/them pronouns.

[3] More than one in ten LGBTQ+ identifying students between the ages of 16 and 24 have experienced rape or sexual abuse at school between the years 2017 and 2019 according to the OUT LGBT Well-Being Survey (Nyeck et al. 2019: 3). In 2016, South Africa stood at number four in the highest female interpersonal violence death rate with 12.5 per 100 000 members of the population (World Health Organization 2020).

[4] Although James Sey (2010: 441) acknowledges Lacanian differentiation between the ‘Other’ and ‘other’ as a distinct category, the other scholars mentioned employ the terms ‘other’ and ‘otherness’ more generally as categories against a western heteronormative standard.

[5] Young’s music video Gendah Bendah (2011) can be accessed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q0RWbVN1ZjE

[6] Lyrics are taken from Young’s Soundcloud

[7] Samuelson refers to Peter Abrahams’ memoir Tell Freedom (1954) and Lewis Nkosi’s novel Mating Birds (1983) which she refers to as ‘black-centred representations of Durban beach’ (2014: 311).

[7] Samuelson refers to Peter Abrahams’ memoir Tell Freedom (1954) and Lewis Nkosi’s novel Mating Birds (1983) which she refers to as ‘black-centred representations of Durban beach’ (2014: 311).

REFERENCES

Abel-Hirsch, Hannah (2020), ‘Zanele Muholi’, hannahabelhirsch, https://hannahabelhirsch.com/Zanele-Muholi (last accessed 30 September 2021).

Ahmed, Sarah (2004), ‘Affective Economies’, Social Text 79, Vol. 22, No. 2, (Summer 2004). pp. 117-139.

Biscombe, Monique, Stephané Conradie, Elmarie Constandius & Neeske Alexander (2017), ‘Investigating “Othering” in Visual Arts Spaces of learning’, Education as Change, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 1-18.

Charmaine, Noncedo (2020), Interview at Victoria Yards, Johannesburg, 7 November 2020.

Charmaine, Noncedo (2021), Interview via e-mail, Online, 21 October 2021.

Emerson, Rana A. (2002), ‘”Where My Girls At?”: Negotiating Black Womanhood in Music Videos’, Gender and Society, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 115-135.

Farber, Leona (2010). ‘Introduction: The address of the other: the body and the senses in contemporary South African visual art’, Critical Arts, Vol. 24. No. 3, pp. 303-320.

Gendah Bendah (2011), dir. d’bi Young.

Gilman, Sander L. (1985), ‘Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-century Art, Medicine, and Literature’, Critical Inquiry, Vol 12. No. 1, (Autumn 1985), pp. 204-242.

Hobson, Janell (2003), ‘The “Batty” Politic: Toward an Aesthetic of the Black Female Body’, Hypatia, Vol. 18, No. 4, (November 2003), pp. 87-105.

hooks, bell (1992), Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston: South End Press.

Mulvey, Laura (1975), ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, Vol. 6, No.3, (Autumn 1975). pp. 6-18.

Nead, Lynda (1992), ‘Framing and Freeing: Utopias of the Female Body’, Radical Philosophy, Vol. 60, No. 12, (Spring 1992), pp. 12-15.

Nuttall, Sarah & Penny Siopsis (2010), ‘Short articles: an unrecoverable strangeness: some reflections on selfhood and otherness in South African art’, Critical Arts, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 457-466.

Nyeck SN, Debra Shepherd, Joshua Sehoole, Lihle Ngcobozi & Kerith J. Conron (2019), The Economic Cost of LGBT Stigma and Discrimination in South Africa, Los Angeles: Williams Institute.

Odunbaku, James B. (2012), ‘Importance of Cowrie Shells in Pre-Colonial Yoruba Land South Western Nigeria: Orile- Keesi as a Case Study’, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 2, No. 18, pp. 234-241.

Samuelson, Meg (2014), ‘Re-telling Freedom in Otelo Burning: The Beach, Surf Noir, and Bildung at the Lamontville Pool’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 307-323.

Sey, James (2010), ‘The Trauma of Conceptualism for South African Art’, Critical Arts, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 438-456.

Smith, Aimee-Claire (2017), ‘The 20 Emerging Black Womxn Photographers in South Africa You Should Know’, Between 10 and 5, 5 October 2017, https://10and5.com/2017/10/05/the-20-emerging-black-womxn-photographers-in-south-africa-you-should-know/ (last accessed 20 May 2021).

Sonnekus Theo & Jeanne van Eeden (2009), ‘Visual Representation, Editorial Power, and the Dual ‘Othering’ of Black Men in the South African Gay Press: The Case of Gay Pages’, Communicatio: South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 81-100.

Stout, Shaelyn (2020), ‘Essay: On Representations of Black Women in Water’, Postscript London, https://www.postscript.london/feature/on-black-women-in-water, (last accessed 30 September 2021).

Van Der Vlies, Andrew (2012), ‘Art as Archive: Queer Activism and Contemporary South African Visual Cultures’, Kunapipi, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 94-116.

Walcott, Rinaldo (2018), ‘Middle Passage: In the Absence of Detail, Presenting and Representing a Historical Void’, Kronos, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 59-68.

World Health Organization (2021), ‘Violence against women’, World Health Organization, 9 March 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (last accessed 20 May 2021).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey