‘I Cannot Be Sure That I Will Not Be Erased or Voided’: In Conversation with Katarzyna Kozyra

by: Aga Skrodzka , June 25, 2022

by: Aga Skrodzka , June 25, 2022

Katarzyna Kozyra is one of the most influential visual artists working in East Central Europe today. Her art explores the material body—especially in its non-normative figurations—and its role in social discourse. In her highly experimental works, Kozyra contemplates the influence of cultural oppression and domination on the symbolic lives of subjects that are excluded from the patriarchal systems of power. Risking public outcry, Kozyra uses her creative agency to imagine, and then methodically materialise, taboo images that challenge the codes of politeness and propriety traditionally used to control and limit those subjects’ presence in the world. She works in new media, but also draws on performance, dance, and choreography. Her experiments with different types of cameras have contributed to a new visual vocabulary and new ways of seeing.

*

Aga Skrodzka (AS): One of my favourite Kozyra quotes is a statement you once made about your creative agency. Namely, you said that your omnipotence gives you confidence to accomplish whatever you wish because you are potentially talented in any area. For quite some time now, I have been quoting this statement to myself before delving into any new project. There is something profoundly edifying in your vision of creative potency. Is there a lesson for all women in this statement? Do you see yourself as a mentor to other women, female artists and creators, women who have something to say? Do you direct your agency, your experience, and your accomplishments to other women?

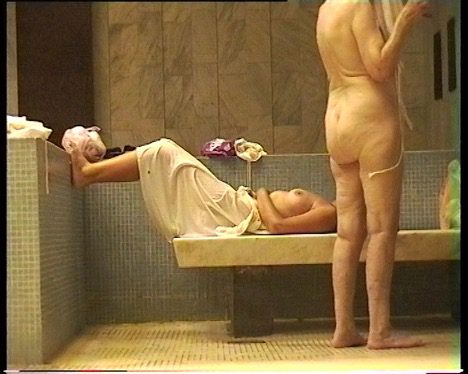

Katarzyna Kozyra: First and foremost, I made that statement to myself. As I was articulating it, I was simultaneously ‘inspecting’ it with great curiosity, but, really, I do believe that creative people are creative in every area. Because people either create or are afraid to create, and thus do not allow themselves to do it. Of course, men inherit the sense of omnipotence through specific acculturation processes and gendered upbringing. So, perhaps, women may feel themselves to be the addressees of my artistic statement. I have not considered it when creating art, but looking now at my experiments, which I made principally for myself, I see how they do concern women or contain the special layer that is uniquely readable, visible, and understandable by women if only they follow in my footsteps and dare to exit the male logic that organises the cognitive universum. If you look at my Bathhouse (1997) and Men’s Bathhouse (1999), you will see the difference in perception; the women’s bathhouse is not about naked bodies and the disparaging look at the ungainly bodies of old women. Instead, that space is about tenderness and mutual care. In the men’s bathhouse, I observed competition and domination, but in order to be allowed to enter that space I had to ‘dress’ as a man and inhabit that space as one.

AS: Aside from your creative activity, I have been watching your work as an organiser and animator of a group of female artists from East Central Europe called ‘Friends.’ It’s one of the many initiatives supported by the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation. Would you mind telling us about this community building project? Was it motivated by the increasingly complicated political and economic conditions in the art world in that region of Europe? How do you see this situation unfolding from your vantage point? What are the unique challenges (and perhaps advantages) of creating art under those circumstances?

KK: First, women artists from this region simply don’t know each other and don’t know about each other. Second, when I talk to the Polish art collectors and art aficionados, those who invest in art and who support me, I find that they only know the Polish female artists and those female artists who have made it to the top of the international art scene. They are not aware of all those exciting female artists from East Central Europe if those artists have not entered the international market. And much of this outstanding art will never enter the international market. Once again, I have to say that thinking about art in market and commodity terms is a misunderstanding. Polish collectors want either national artists or international celebrity artists.

In my answer to your question, I’d like to clarify a few things. The ‘Friends’ project has been conceived as an initiative that supports the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation. In turn, the foundation supports female artists from the region. The ‘Friends’ are a group of artist friends of the foundation, who help us conduct outreach in the name of artistic and female solidarity. The ‘Friends’ donate selected art works, which we issue in limited editions. Those objects then become tokens of appreciation for the patrons who wish to support the foundation. This exchange cements the relationships between the sponsors and the artists as well as the relationships among the artists. It also works to educate the collectors and to disseminate the works of the artists who are not sufficiently known. The first collection— ‘Friends 2019’—consists of my works alone. It takes the form of Duchamp’s boîte-en-valise. The second collection—‘Friends 2020’—includes works by female artists from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland, the so-called Visegrád Four. Why this choice? Well, we are simultaneously providing a transnational collaboration and publicity platform for female artists from these countries. We are interested in hearing from each artist as she defines herself as an artist, a woman, a human, an East Central European. We are collecting and sharing the artist’s statements from living artists, but also composing statements for female artists from the past, reconstructing their identities and creative visions. Thus, we are producing an archive that will allow us to learn about each other and educate others about our art. While we know about the female artists from the West and from Russia, we still don’t know ourselves, the artists from the somewhat overlooked and ignored liminal region of East Central Europe. In constructing this community platform, we are assisted by the curators and art institutions from the Visegrád Four countries. At the inception of this initiative, we had to make some choices, and I am fully aware that some of the very deserving artists did not get included in our first unveiling of the project, but we intend to extend our reach and include artists from other locations. I hope to widen and deepen the scope. For example, this year we are joined by female artists from Ukraine and Belarus.

Why this initiative? First, women’s voices are still not sufficiently heard. The art statements of male artists—even the statements that are poorly formulated and only partially thought-out—get promoted and circulated before and ahead of the most insightful statements by female artists. Second, throughout East Central Europe, there is still a minimal or non-existent art market, and the art market functions as a communication platform, not a perfect one, but a platform that disseminates knowledge on some level. In those countries of the region where there is a semblance of an art market, it predictably focuses on male artists. Generally, though, the system is very rudimentary. There are few galleries, few artist-run spaces, little public support, and the idea of arts patronage is not popular. Consequently, female artists have slim chances of being heard and seen. The political atmosphere is also difficult for female artists. Just look at what is happening now to women’s rights in Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia. But there is a unique silver lining here as well—this lack of art commercialisation and commodification leads to the conceptualisation and creation of art that is more emphatic, more diversified, and free of market limitations, thus more interesting for me. Under these conditions of scarcity and political hostility, art is not conceived as a product for sale. As such, this art does not have to be pretty, canonical, or schematic; it can afford to be shameless, insolent, brutal, or unsightly. It can address inconvenient truths and problematic issues. Art created outside of the art market has a completely different dimension and an independent point of view. This kind of art thinks differently. In this context, the voices of the female artists often participate in social and ideological debates. Their art provokes a different view of the world by bypassing and destroying stereotypes.

I feel that the culture and mentality in this part of Europe continues to situate the woman not as a human or a partner, but as a wife, mother, lover, and caregiver who must serve, nurture, assist and be available at all times to the superior male subject. This paradigm is so deeply ingrained in our culture that even the so-called liberal men, who are educated and politically progressive, still practice the subjugation of women, often completely oblivious to the effects of their words and actions. Let’s recall how in the very recent history of the Polish Women’s Strike (the pro-abortion movement), the liberal men joined in and offered their support using outrageously patriarchal arguments for why they decided to stand with their women. They lacked the self-awareness and the understanding of how their motivations were in fact reactionary. They are really sweet, but we, the protesting women, are often embarrassed by what the liberal men say. For example, some of the men who protested alongside women, who were demanding access to free and unrestricted abortion in the fall 2020 and spring 2021, explained their support for the initiative by saying, ‘we are here for our ladies, who organise our world and tend to it so beautifully. Now they are in the streets. We must help them!’

AS: The Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation is also sponsoring research projects. One of those projects led to the fascinating report about the presence and participation of women in Polish art academies. Conducted by a group of female art scholars, sociologists, anthropologists, and economists, and titled ‘Poor Chance to Advance?’ this report documents the gender gap between female students and female faculty in the art academy. The report sheds light on the long-standing disproportion between the female art students, who constitute 77% of the student body, and the female art professors, who constitute only 22% of the professorial staff. What is the effect of this situation on women graduating from art academies? Did this gender gap impact your art education? Can you imagine an alternative history, where Katarzyna Kozyra would be able to defend her diploma under the tutelage of a female artist, and not in the studio of Professor Grzegorz Kowalski? Or, to rephrase this question, what influence did the gender gap in your art education have on your artistic vision?

KK: It’s hard for me to say what could or would have been, but it is quite evident that art academies, just like most of other institutions, are governed by the uniquely male logic of power. It’s a system where men are awarded the primacy—they get promoted; they are appointed because they are still perceived as the breadwinners of the family. Ostensibly, they need the appointment and the promotion because they must earn a living. Women are not treated seriously as professionals because they are framed as those who stay home to give birth to children and then care for them as well as care for the house and the domestic life of the men. In academic art studios, the male logic governs the work and the treatment of students. In this respect, even the most progressive art professors can be sexist. Maybe without even being consciously sexist, because sexism is the norm. If there were more female art professors, the DNA of the art academy would undoubtedly change. At the moment, even if a solitary female artist gets lucky and is promoted to professorship, she has to play the game of paternalism, domination, and oppression. When it comes to the impact of this system on my own academic education, I had not thought about it while being a student, or after I had graduated. I simply did my thing. Although right now, as I reflect back on that early stage of my career, I realise that some of my choices were determined by the need I felt to prove to myself and others that I am at the right place and can do all the things that were expected of me and more. That was why I sculpted the helmets out of concrete. I had to show to my teachers that apart from making a sculpture about anorexia with the use of wire and clay, I could also sculpt the fuck out of concrete. As I’m now unpacking your question, I’m thinking that women at the art academy, both students and the rare female faculty, were and still are automatically treated with condescension. The institutional culture and logic of violence and oppression made that possible. Further, the women who ascended to positions of power within this system, created by and for men, feel somehow obligated to replicate the men’s behaviour, perhaps, to consolidate their precarious position in the men’s world. These are the women who laugh at the men’s sexist jokes and retell those jokes to others.

AS: My professional focus of a scholar who works primarily in cinema, studying photographic and cinematic images, makes me enter and appreciate your art through those channels. I like that you always document your performance art using a camera, thus providing those performances a more permanent life. As a result, you preserve and immortalise your body, the body of a female artist captured in the act of creation. You ensure that you and your art will not be erased from art history. What is your intention, now after a few decades of working as a visual artist, with regard to the role of the camera, the photographic, and the videographic expression? How do those media serve your art and your mode of expression? What determines your media choices?

KK: I beg to differ on the issue of ensuring my legacy. I cannot ever be sure that I will not be erased or voided. Look at Marie Skłodowska-Curie. She had to be erased before she was commemorated with pomp and circumstance. There are plenty of women who laboured, and continue to labour, to deliver first class achievements, but are mainly seen as the wives of some men. And not every one of those women will be rendered visible. When it comes to the kinds of media, I make my choices depending on the subject matter. In the end it is not the medium that determines my art. Rather, I determine the best medium. In that regard, Leni Riefenstahl has pioneered the innovative approach to the camera and its capabilities. She never allowed the camera technology to limit her view. She dictated what her camera could do by designing ways to optimise its use by building special elevator platforms, using rails, digging trenches, putting her camera operators on roller skates, and sending automatic cameras into air with the help of balloons.

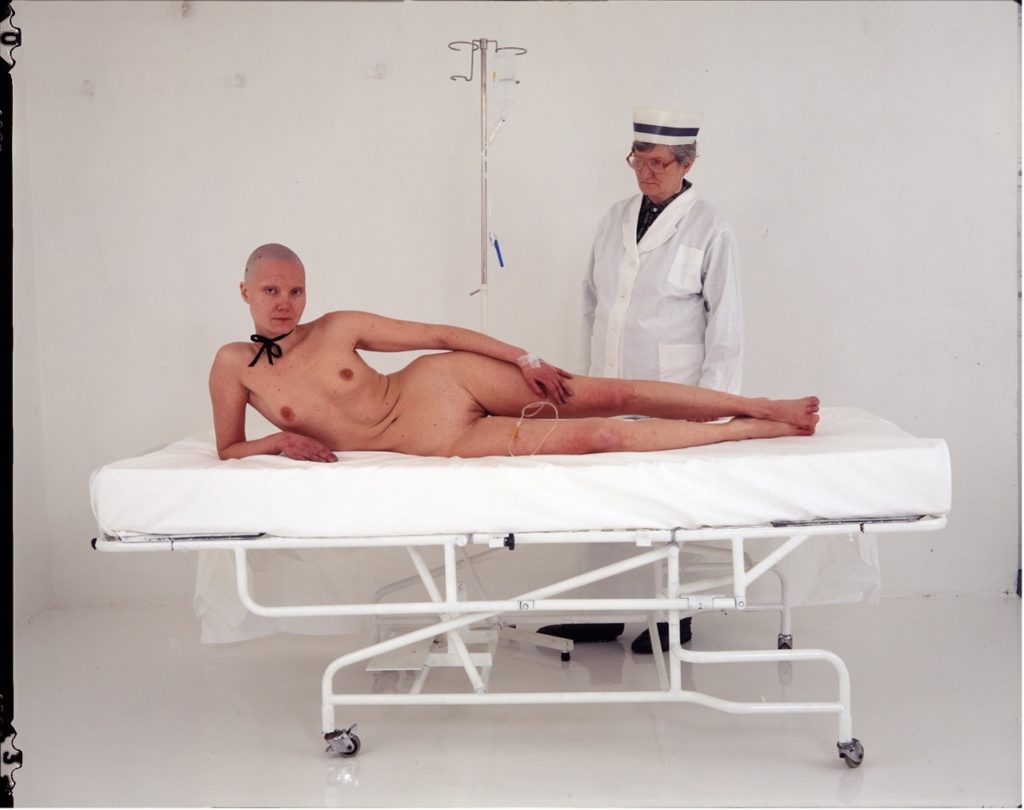

AS: Her collaborations with the Nazi propaganda machine have compromised her legacy and exposed her naïveté, but her film production innovations did transform the ways that the human body, especially body in motion, could and would be viewed for the rest of cinema’s history. It’s interesting that you mention Riefenstahl, because I have always viewed your work Olimpia (1996), which focuses on the stigmatised, sick body of the female artist—the body attacked by cancer and ravaged by chemotherapy—as direct sendup of Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), which creates and champions the idealised, ableist athletic body.

KK: That’s intriguing what you’re saying, but my Olimpia was not a reaction to Riefenstahl’s Olympia. In my work I engaged with a certain tradition in fine arts that treats the female body as an ornament, an accessory used for sexual stimulation, maybe even masturbation. Specifically, I was thinking about the 1863 painting by Édouard Manet titled Olympia. Upon its exhibition, the painting sent out immediate shock waves and disturbed the refined tastes of the French public, because suddenly the woman—an object—is gazing back at the subject, the intended male viewer, the male voyeur. She dares to return the gaze. In this Manet painting the woman-as-object is gaining subjectivity thanks to her confrontational gaze, which is not modest (as the female gaze was coded), not duplicitous, not choreographed for the optimal pleasure of the looking subject, who is assumed to always be male. On top of it, Manet’s Olympia is receiving flowers from a sponsor. What audacity! It is commonly believed that Olympia was a famous courtesan, but the model who depicts her was herself a painter, whose works were frequently exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon. But this fact is only now being discussed.

AS: Yes, the painting also depicts the Black female who is handing the flowers over to Olympia. This female remains the object, not erotic, but domestic. The difference between Olympia as an erotic object and the Black servant as the accessory to the White erotic object points to the racist hierarchy that shapes the sexist hierarchy.

But to return to the discussion of your art experiments, I look at your art from the early 1990s onwards and I see how consistently and systematically you visualise cast-out and non-normative bodies. In your projects we meet bodies that are disabled, sick, ageing, queer and hybridised. In an effort to tell us something new about these bodies and their place in our culture, you experiment with your camera. Would you please tell me how you approach these experiments?

KK: For example, in Bathhouse, I hid my camera not on my body but in a plastic shopping bag, with an opening cut out for the lens. I was not able to frame what I was filming in established, professional ways because I had to pretend that the bag was carrying my toiletries, not a camera. The bag would sit next to me on a bench and wait till someone walked into its view. Or I would carry it around as one carries a shopping bag if I saw something interesting happening in the bath space. In this way the world gets to be framed anew and afresh. There arises a multiplicity of planes, which are populated by independent actions (this effect resembles in-camera editing), new perspectives, and a new directionality of looking. In this gaze of the hidden camera there is a dose of Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt. My camera recorded the women in the bathhouse and the space of the bathhouse offhandedly. Consequently, the women’s actions and the relationships among them, not their bodies, became important. In some way, this experiment with the hidden camera allowed me to critique patriarchal visuality. Further, and what I like the most, there is the way that this camera fashions a look that is utterly alien or something like the look of a non-human species observing the human.

![Men’s Bathhouse, 1999. Artist in disguise. [Video still]. Photo by Katarzyna Kozyra. Courtesy Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation.](https://maifeminism.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/4.jpg)

AS: Now, after many decades of experimenting with different kinds of cameras, how would you describe your relationship with the camera? What is the camera for you in a philosophical, and maybe political, psychological, or even personal sense?

KK: The camera is a tool and a co-witness. It is a recorder of what is and what happens in reality. It’s a unique ‘authenticator’ that brings credibility, because not everything can be described in words. From these elements captured by the camera, one can construct an alternate reality.

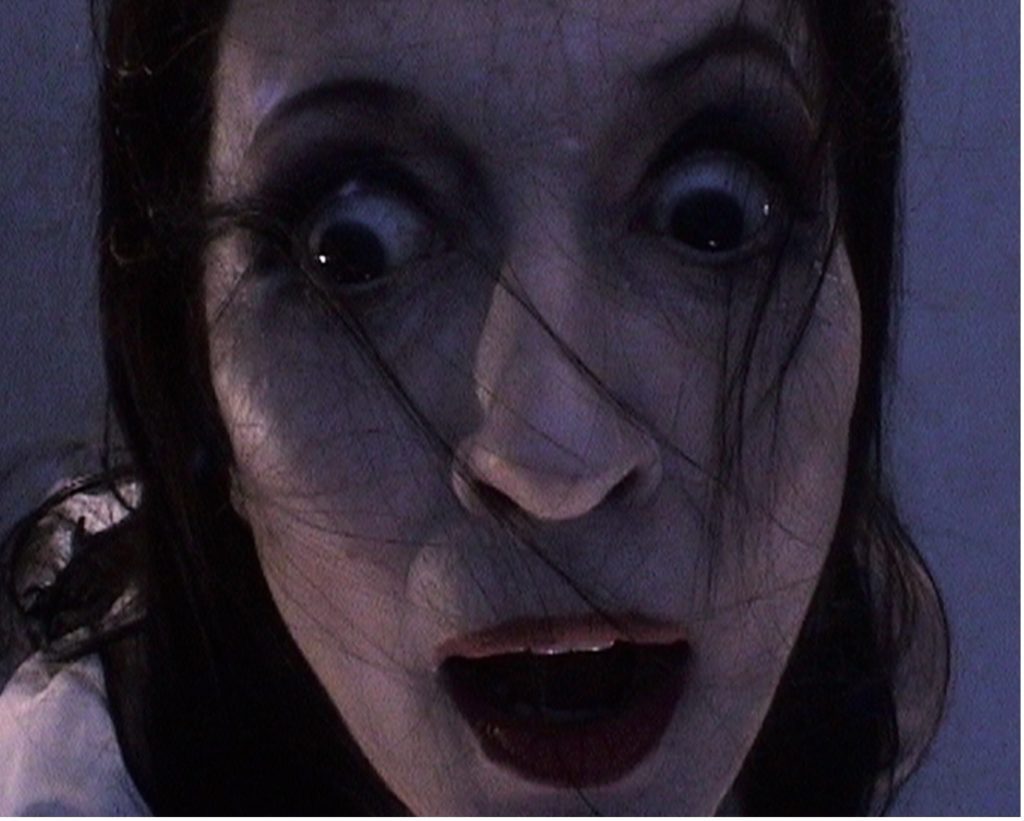

AS: When I look at your Faces (2006), where you equipped professional dancers with cameras rigged on their foreheads to record facial expressions during dance, I see how your experiment has forever changed our perception of those perfect bodies. In Faces we see that dance is not this unforced movement of beautiful bodies that glide across the stage, magically performing perfection. Suddenly your intimate face cameras unveil effort, strain, painful transformation, and mixed affect. Like the Soviet montage filmmaker, you install the camera where it is going to show us something completely unexpected, the Vertovian kino-pravda. Do you think about yourself as an innovator of vision and visuality?

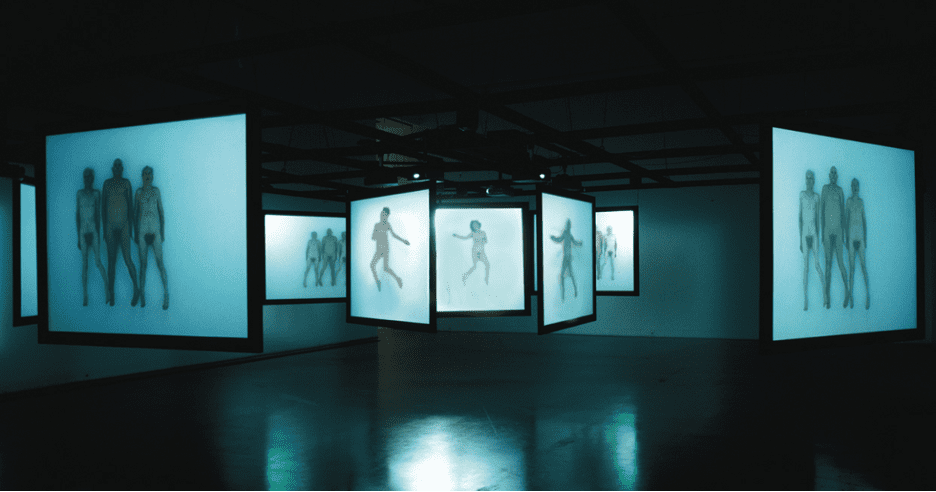

KK: Thank you for the analogy. In a sense, Faces took the next step after The Rite of Spring (1999-2002). There I used a film camera to take aerial photographs of the elderly naked performers, who were arranged on the set by me and my animators. Those frames had to then be cleaned up from partial images (because I used a film camera to take the photos) and edited into an animated film. At that stage of my work, I was very interested in the impossible choreography of the whole body, in setting the body. In Faces, I gave the dancers small cameras strapped to their heads and facing their faces during dance. At that time, I did not anticipate a specific result. I simply wanted to deepen the view and that’s it. Usually during dance performances, we sit quite a distance away from the dancers’ moving bodies. The lucky few sit in the first row. I was interested in capturing something in the dancers’ faces, and this something turned out to be completely contrary to the studied choreography of their bodies. For example, we get to see the involuntary signs of exertion–the sweat on the brow, the swollen veins, and grimaces.

AS: Do you think of your art as a form of resistance?

KK: My art is my art. Some see it as art of resistance. I guess, I do, too. My projects often originate in discord. Many see my art as a mere provocation. For me it is about new undertakings, new projects that take me into the unknown territories, so that I can research and learn something.

AS: And now a few questions shaped by the current circumstances. What does the female artist do during the COVID pandemic?

KK: The artist is cleaning up, sweeping, and organising. She is also absorbed in, and working on, Jesus (Looking for Jesus is my latest, multi-year project). Additionally, the artist is working with the foundation. She travels much less and reads much more. The artist is tending to her wounds after an unfortunate fall from a tree. When she is in good form, she is digging away in her garden in central Warsaw.

AS: What have you read recently?

KK: A mix of things–Hate, Inc. by Matt Taibbi, Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men by Caroline Criado Perez, This is War: Women, Fundamentalists and the New Middle Ages by Klementyna Suchanow, and Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations by Ronen Bergman.

AS: What does the Polish artist do when the government is hell-bent on reducing the Polish woman to a reproductive machine?

KK: She was reduced a long time ago. All of us wear burqas, but in some places, they are less physically visible. The Polish artist is also following the news at the independent OKO press portal, and she is trying not to give in to rage, and not to boil over.

AS: What does the artist do in a country where the right-wing organisations along with the government have recently set up ‘LGBTQ-free’ zones?

KK: The artist refuses to acknowledge these. This disgrace, however, does lead to the formation and consolidation of new resistance movements. One can hope that this bigotry and unapologetic thuggery will be met with a sharp turn to the Left.

Most of the time, though, I hunker down and work on my art and the foundation initiatives to help other female artists.

*

Learn more about these initiatives and the ways in which you can support them: http://katarzynakozyrafoundation.pl/en/foundation/

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey