Her Story: On the Possibilities of Trans Short Form Media

by: Laura Stamm , October 5, 2020

by: Laura Stamm , October 5, 2020

Her Story (2016), the web series created by trans actor and activist Jen Richards, took both audiences and critics by surprise with its authentic and groundbreaking presentation of a trans love story. The series was nominated for a 2016 Emmy in the category of Outstanding Short Form Comedy or Drama Series, alongside web content created for network cable channels, including Comedy Central, Lifetime, and AMC. [1] With the rise of binge-watching formats and distracted spectator practices, short form web series cater to a growing desire for complete narrative arcs in a compressed timeframe. [2] When Her Story screened at queer film festivals, in fact, programmers screened all six episodes back-to-back in a film slot, as if it was a feature film. [3] The web series format also appeals to independent directors and producers because it allows them an opportunity to create their work with low production costs and reach a wider range of audiences than traditional-format series that screen on cable or premium streaming channels. Because the series targets marginalised audiences (queer, trans, and trans people of colour) who are disproportionately unlikely to be able to afford cable and streaming platforms like Netflix and Hulu, Her Story’s web platform provides wider access to its most important viewers. YouTube’s platform further allows for a global audience and viewing community because it does not have region restrictions, and content can easily be translated into other languages with user-generated subtitles. By 2016, only shortly after the series’ release, Her Story fans had translated the series into 10 languages, and it had been watched in 127 countries. (Film Independent 2016)

In recent years, short form media on YouTube has allowed queer audiences to find the kind of mirroring representations they have never had available to them in mainstream media. For instance, the Canadian web series Carmilla (Jordan Hall and Ellen Simpson, 2014-2016), a vampiric lesbian love story garnered a young lesbian global cult following. Audiences’ adoration of Laura (Laura Hollis) and Carmilla’s (Natasha Negovanlis) love story spun off into online fan communities with users producing fan fiction and original art. [4] The queer viewership and fandom for Carmilla even lead to a feature length film titled The Carmilla Movie (Spencer Maybee, 2017). Carmilla proved that YouTube is a platform that enables audience visibility, and the series arguably made possible lesbian web series that would follow, such as the Canadian web series Barbelle (Gwenlyn Cumyn and Karen Knox, 2017- ). [5] Her Story enters into this market alongside other trans web series, such as Brothers and Eden’s Garden. [6] However, while many web series have effectively used YouTube as a launching pad for gaining network distribution, none of these critically acclaimed trans web series have been able to do so.

While Her Story’s independent production and YouTube streaming platform provides wider access and possibilities for audience engagement, it also begs the question of whether or not trans stories told by trans people can become mainstream. Trans representations produced by cisgender (from here referred to as cis) producers, such as Transparent (Jill Soloway, 2014-) and Pose (Ryan Murphy and Steven Canals, 2018-), appear to have no problem garnering financial support from investors and producers. [7] Furthermore, while many recent series, including Freeform’s Good Trouble (Joanna Johnson, 2019-) and HBO’s Euphoria (Sam Levinson, 2019-), have featured trans characters, these characters support the series’ protagonist’s narrative instead of having their own. Richards’ recent role on HBO’s limited series Mrs. Fletcher (Tom Perrotta, 2019- ) as protagonist Eve’s (Kathryn Hahn) community college instructor, Margo, serves as a prime example. Eve decides to register for a course on personal writing, and this decision thrusts her into a classroom and flirtation with a young man the same age as her son. Eve’s sexual transgressions are paralleled, or perhaps supported, by Margo’s own romance narrative as a trans woman dating a cis black man. Richards’s character does get a romance narrative, but it once again serves the show’s larger plot lines. Network television series appear willing to incorporate supporting trans characters and narratives, so long as they can easily write them off the show if need be.

Television networks’ apparent reluctance to centre a trans character’s story raises questions about the types of trans representations networks think audiences want to see. The lack of authentic trans representations set in our current historical moment suggests that narratives revolving around love and everyday concerns are reserved for heteronormative (and homonormative) characters and storylines. Dominant media frequently misrepresents trans bodies and experiences, which produces trans viewers’ need for authenticity, or felt authenticity, in alternative trans media. [8] While no media object can ever present a truly authentic experience, only the effect of authenticity, some representations ring truer than others. Like all viewers, trans viewers still crave mirroring images of themselves that create a feeling of recognition. Her Story’s authentic portrayal of trans experiences is a direct result of trans women’s participation in every level of production in front of and behind the camera, including writing, producing, and acting. The series first introduces the audience to Allie (Laura Zak), a cis lesbian reporter and writer for Gay LA magazine, on the lookout for the subject of her next story, a glimpse into what the LA dating scene looks like for a trans woman. From here, the series introduces Violet (Jen Richards), a trans woman bartender, and Paige (Angelica Ross), a black trans woman lawyer for Lambda Legal and one of Violet’s closet friends. When Allie decides to write a piece on what it means to be a trans woman in LA, she approaches Violet, the only trans woman she has seen in person (or so she thinks), to tell her story. Allie enters the interview with the intense curiosity and voyeurism characteristic of many cis people’s thoughts about trans people, but her time spent working on the piece with Violet soon leads her to question her own assumptions about the queer community.

Troubling Gay LA

Allie and Violet begin the interview process for her Gay LA story during Episode 2, with Allie asking questions that are ‘too personal’, for example whether Violet was gay before transitioning, assuming that if Violet dates men now, she must have dated men in the past. Violet explains that there is no ‘normal’ for sexual preference after one transitions, and ultimately, her attraction to men stems from the assurance she feels with them. Violet states, ‘When I’m with a man, I have no doubt about my womanhood.’ She explains that next to a man’s body, her body appears obviously feminine, but next to a woman’s body, her femininity becomes precarious. The scene’s shot-revere-shot construction places the viewer’s identification with Allie, as she realises that she ‘doesn’t know shit about transgender issues.’ Allie does not know what it is like to wonder if people notice the size of your hands or are clocking the pitch of your voice. She does not know what it is like to fear the consequences of not passing. She realises, hopefully as cis viewers realise, that she does not know anything about what it is like to live as the T (trans) in the LGBTQ acronym.

The series tackles transphobia within the lesbian community through Allie and her friends, who could easily be confused as a rival lesbian clique from The L Word (Ilene Chaiken, 2004-2009). But instead of glamorising the image of LA lesbian identity, Her Story critiques its foundational exclusions. The lesbian community’s, as well as the feminist movement’s, all-too-frequent exclusion of trans women usually stems from a biological essentialist understanding of gender, womanhood specifically. Allie’s friend Lisa (Caroline Whitney Smith) exemplifies many of the trans-exclusionary radical feminist (TERF) beliefs present in the lesbian community, and demonstrates the ways in which seemingly progressive feminists often marginalise trans woman. [9] Lisa defends her beliefs that trans women are really men by arguing that trans women put cisgender women in women’s shelters at risk at a time when these women are at their most vulnerable. She defends her transphobia through her supposed defence of cis women’s rights. While viewers will likely recognise (and perhaps initially share) many of Lisa’s beliefs and arguments, viewers are taught alongside Allie to see the hypocrisy in trans-exclusionary ways of thinking. As the series progresses, and Lisa continues to purposely misgender trans women and deny their inclusion in the LGBTQ community, she becomes an abhorrent figure. The series portrays Lisa almost as villainously as Violet’s abusive partner Mark, equating her transphobic slurs with the physical violence trans women experience. [10]

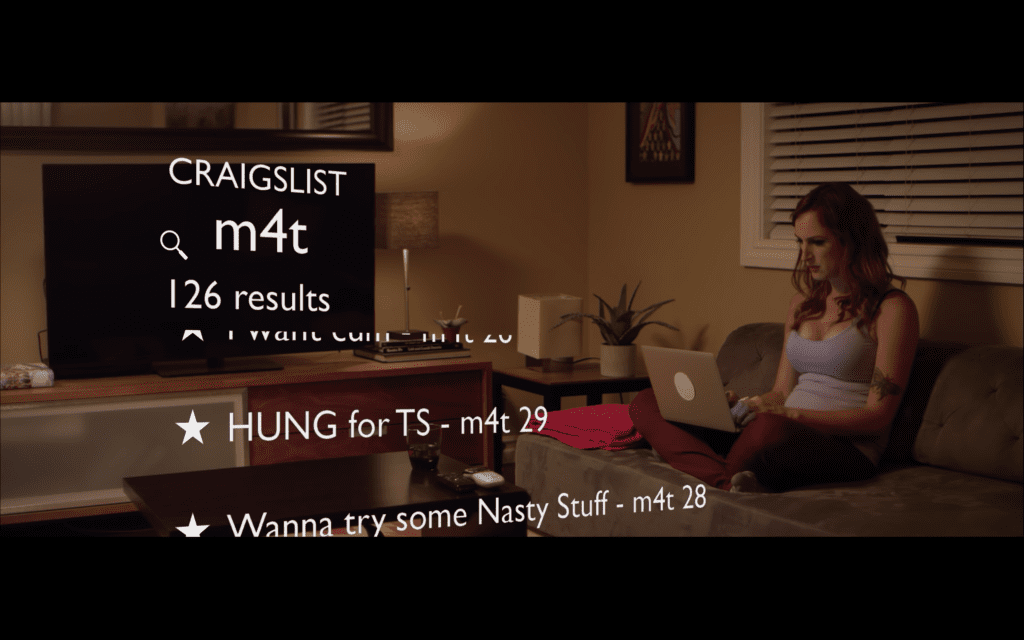

Zak and Richards originally met while working on the web series #Hashtag (Caitlin Bergh), a Chicago-based lesbian web series that ran from 2013-2015. (Film Independent 2016) #Hashtag, it is worth noting, is not available to stream for free on YouTube, unlike Her Story. While users can stream the trailer and the first episode for free, the rest of season one and all of season two requires a Tello subscription. #Hashtag explores queer relationships and dating in the age of social media. From the first episode, Liv (Zak) feels the effects of her Instagram obsession (and flirtation) on her relationship with the latest OkCupid crush. Richards appeared in a cameo as a waitress Zak’s character flirts with in a café, and that brief flirtation inspired the idea for a spinoff series centred on their budding romance. Her Story was, thus, initially conceived as a trans extension of the lesbian dating world portrayed in #Hashtag. Within the first two minutes of the first episode, Violet searches Craigslist for potential suitors. As Violet sits home alone on the couch, the search results pass over her image in superimposed text. Her search for men interested in trans women reveals that these men want a trans woman willing to fulfil their fetishistic fantasies or a passing trans woman willing to conceal her identity. Her search from women looking for trans women produces zero search results. This casual Craigslist search sets the tone for the series’ exploration of both Violet’s and Paige’s dating lives.

Richards, Ross, and the rest of the Her Story team used social media to reach out to trans viewers and successfully built a network of people not only interested in watching the series, but also interested in funding it. [11] The budget of the original project was only about $10,000 and Richards conceived of the series as a fun project to show their friends. When Katherine Fisher signed on to produce the series, she immediately doubled the budget to lend the series the production quality she felt it deserved. In the end, the final budget for the project ended up around $150,000, making the project much larger than Richards, a first-time writer and creator, could have predicted. (Film Independent 2016) The production team used web platforms at every level of production and distribution, from marketing and crowdfunding to streaming and live screening events. While a teaser of the series screened at NewFest, with a panel discussion led by Laverne Cox, Her Story’s official launch took the form of a public screening at California State University, East Bay. After the series then screened at OutFest, the team embarked on a college tour for screenings discussions with college students and faculty, using social media to alert local audiences of their arrival.

Possibly more than any other social media platform, Twitter provided a way for the crew to connect with audiences, both famous and not so famous. Many of the series’ production team members, including Zak, Ross and Richards, already had a strong following from the queer community, which meant that tweets about Her Story reached a pre-existing audience. [12] Twitter provided a built-in audience of followers, including celebrity friends, who anxiously waited for the series’ launch. Tweets from celebrities such as Kerry Washington, Janet Mock, and Laverne Cox became part of the team’s press campaign and pitch for the Emmy nomination. These tweets became a way to claim legitimacy and a space within the film industry.

Yet, what may make the project so successful is the way the series does not stop at finding its trans and queer audience members, but reaching further to connect outsider (cis and straight) viewers to the trans experiences. While Violet (understandably) initially approaches Allie with reluctance, she finds companionship and romance over the process of their interview. Allie often makes the mistakes many outside of the trans community might make, asking inappropriate questions and misusing trans terminology, making her an accessible point of identification for cis audiences. As Allie and Violet’s pedagogical relationship develops, so too does the audience’s learning and understanding of trans issues and identity. This identification places cis viewers in the position of an outsider encountering trans women, and developing a new queer consciousness. [13] The series shows cis audiences that their experience of gender is one experience, but it is not the only one. Through moments like Violet’s conversation about her voice, the series exposes the process of gendering—distinguishing between men and women (according to binary models of gender)—and daily anxieties trans people experience out of fear of being inappropriately gendered. While the process of gendering may seem like a passive process of noticing, trans writer Julia Serano argues the opposite. People actively gender compulsively; although most cisgender people do not realise how and when they compulsively gender others, trans people acutely see and experience their gendering. (Serano 2007)

Modes of Trans Media Production

The education of cis audiences is directly tied to Richards’s activist work, specifically her critiques of Hollywood’s history of having cis male actors depict trans women characters. Richards insists on a link between mainstream media’s portrayal of trans women by cis men and material violence against trans women. In Variety’s 2018 ‘Transgender in Hollywood Roundtable,’ she explains to viewers that if a cis-woman plays a trans woman, the film is saying that a trans woman is a type of woman; but if a cis-man plays a trans woman, the film is ultimately saying that a trans woman is a type of a man. [14] These portrayals, as seen in Dallas Buyers Club (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2013), The Crying Game (Neil Jordan, 1992), and The Danish Girl (Tom Hooper, 2015), perpetuate the notion that trans women are deceptive, a notion that stands at the root of material violence against trans feminine people. This continual recurrence of cis actors playing trans characters not only takes away already scarce opportunities from trans actors, but it also reinforces dangerous cultural beliefs about trans women in particular. This image of a man in a dress who attempts to ‘trick’ straight men into sex is one that leads to much violence against trans women, and specifically trans women of colour.

The ever-expanding realm of the digital, and YouTube specifically, has allowed trans content creators to speak back to mainstream media’s representations by telling their own stories. Oftentimes, these amateur videos take the form of direct-address, blog-style narratives with the video’s creator speaking into the camera about their transition, new makeup techniques, or feelings about their identity. Laura Horak in ‘Trans on YouTube’ argues that conventions of trans YouTube vloggers’ videos create a connection between their creator and viewer that can counter objectifying media portrayals of trans bodies. Horak explains, ‘YouTube’s predilection for the personal and the spectacular have made it a powerful tool for some trans people to construct the ways that their bodies are looked at and heard—and to connect geographically disparate people in intimate ways’. (2014: 581) The direct address style of most trans vloggers’ videos requires the vlogger to look directly into the camera, and thus directly at the viewer, breaking the fourth wall and creating conversational viewing practices. This low-tech self-generated media genre, through these conventions, has the potential to create trans communities for individuals who may not know another trans person in their physical surroundings.

These vlogs are explicitly pedagogical in that they teach trans viewers how to transition and/or live as a trans person; they also teach cis viewers about trans experiences. Horak only discusses the way that trans vlogs can create community and conversation within the trans community. However, I would argue that these videos also possess the potential for empathy-building and connection between trans vloggers and cis viewers. While trans vlogs on YouTube might be a bit too niche for the average cis YouTube browser, the video-making practices Horak describes do not only belong to transition vlogs. Rather, I suggest that these conversational modes of videomaking can serve as a sort of model for or precursor of narrative trans representation. Media does not need to be explicitly pedagogical in order to teach viewers empathy for others. Her Story’s conversational sequences between Allie and Violet formally mimic the direct address videos of trans YouTube users. In these scenes, we have Violet, a trans woman, sharing her story with Allie, a cis woman reporter. The shot/reverse-shot construction used to filmically tell Violet’s story builds viewers’ empathy with Violet’s experiences through their identification with Allie. From the beginning of the series, cis audiences are most likely to identify with Allie; not only because she is ‘like them’, but also because the series’ cinematography privileges her point of view.

The ways that trans women become visible in mainstream media have severe consequences for the material lives of trans individuals. Trans representation is always both a problem of visibility and invisibility. Representation is crucial, but the wrong kinds of representation are literally life threatening. Horak even suggests that all representation is dangerous, asserting, ‘Even when representation is ‘positive,’ increased media attention to trans people correlates with higher rates of violence and political backlash. While some trans actors have new opportunities many trans women of colour are at increased risk. When trans people are granted mainstream visibility, it is often as spectacularised objects of suffering, not as political speaking subjects’. (2018: 203) Too often, trans women are used to create a certain type of tragedy porn, a porn in which cis audiences are able to voyeuristically consume trans women’s excessive suffering. Representations that reflect trans death and oppression to cis audiences further serve to marginalise trans people by only portraying trans life when it is destined to end. These representations satisfy viewers’ spectatorial desire for tragedy, while also implying that trans lives cannot be made liveable within dominant society. [15]

When I screened the web series in one of my classes, a student commented that she braced herself throughout the six episodes, preparing for one of the beloved main characters to die. While this comment may seem jarring, it points directly to Her Story’s revolutionary potential. The bracing she described suggests the spectatorial expectations all viewers bring to trans media representation, expectations that stem from films like Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999), Albert Nobbs (Rodrigo García, 2011), and Bernice Procura (Allan Fiterman, 2018). Mainstream viewers, as this student pointed out, are used to seeing trans narratives that revolve around tragedy and their eventual death. These tragic trans narratives, perhaps more than anything else, suggest that living one’s life as a trans person is at best dangerous and at worst impossible. Most cis viewers have seen very few (if any) representations of trans people, and the few representations they do see powerfully shape how audiences consciously or unconsciously think about trans people and their experiences. Even if producers intend to raise awareness about such crimes, representations of violence against trans people reinforce the idea that trans lives only have meaning in the context of violence. Her Story jolts viewers with its refusal to tell a story of trans tragedy. While it does portray substance abuse and domestic violence, issues that disproportionately affect trans women, these struggles are only minor aspects of Violet’s story. Her Story shows viewers that Violet’s struggles do not make her life a tragedy. Rather than relying on narrative short hands and generic expectations, the series places audiences in a new diegetic world, a world created by trans women who live lives not so unlike their own.

Searching for Audiences’ Desires

Although Allie begins the series as an outsider to the trans community, her relationship with Violet changes both her understanding of the trans community and her subjectivity. Episode four opens with a voiceover monologue, in which Allie explains,

I had always thought myself firmly on the progressive side of every issue, but like too many in our community, I thought my tacit acceptance of the reality of trans people was sufficient. I never questioned their total absence from my world. I now see that our great disservice is not just to those we’ve excluded, but to ourselves. For our world is less rich without their stories, their laughter, their voices.

The monologue provides a voiceover for a montage sequence of Allie and Violet exploring the city together, talking, taking photos, running across Venice beach, and finally embracing in a hug and leaving the beach side-by-side. This opening comes at the halfway point in the six-episode series and marks a turning point in Allie and Violet’s relationship. Throughout the interview process, Allie realises that including trans people in the queer community in name only does little to actually change the way lesbians like Lisa think. Nominal trans representation does not lead to actual trans inclusion. Beyond this realisation, however, Allie begins to realise how her own world becomes much richer with Violet in it.

Again and again, the series positions its viewer to identify with Allie’s perspective, which, in this case, also means identifying with her education. While LGBTQ media often seeks to educate its viewer through a pedagogical form, Her Story’s pedagogy does not invoke explicitly pedagogical modes of representation. Rather, the series performs its pedagogy through viewers’ identification with Allie throughout her process of transformation. Over the course of the series’ six episodes, Allie’s outsider gaze transforms into one of desire, relationality, and closeness. The first episode opens with Allie and Lisa grabbing a drink and discussing Allie’s next Gay LA piece in the bar where Violet happens to work. As Allie begins to formulate her pitch for a story about trans women dating in LA, her gaze shifts to Violet. Allie approaches her piece for Gay LA with an almost ethnographic gaze, gazing at Violet’s body to determine her gender before choosing Violet as the object of her study. Despite her best intentions, Allie views the trans community as occupying a world entirely separate from her own. Allie’s scrutinising, outsider gaze characterises her initial interactions with Violet, but as their relationship develops, that gaze shifts. Her outsider, objective reporter gaze becomes an insider one, transformed by her desire for Violet.

As Allie and Violet’s relationship develops, Allie shares the formative experience that led her to pursue journalism, the moment in which Allie realised ‘the power of a true story well told.’ In high school, Allie ran an underground newspaper, and at this same time she heard that three teachers at her school were harassing female students. Understanding that the students were too afraid to speak out, Allie decided to write a piece about the ongoing harassment, telling a truth about something she didn’t suffer herself, as she puts it. The story ultimately put an end to the teachers’ inappropriate behaviour and solidified the power of Allie’s work. The goal of journalism, and perhaps any form of storytelling media, according to Her Story is to amplify the voices of those who may not otherwise be heard. Through their identification with Allie, the series encourages cis audiences to understand their role in trans oppression and take responsibility for their own involvement in perpetuating cultural stereotypes, even if that involvement is one of complacency.

Her Story seeks to reveal ‘the power of a true story well told’—to tell many of the truths of trans women’s experience that mainstream trans representations often elide. Richards has said that the series is loosely autobiographical, but the stories it tells extend beyond just her own. During a press interview for the series, Richards exclaimed, ‘People keep calling [Her Story] ‘Innovative!’ and ‘Groundbreaking!’—but it’s a fucking love story! People like me have always been a punchline for the straight male characters. But what’s her story? Now all of us who’ve been ‘other-ed’ by straight white men have a chance to explore that’. (Matz 2016) The series’ status as ‘groundbreaking’ makes explicit how limiting most media representations of trans experience have been. While not only denying the existence of material trans bodies by casting cis actors in trans roles, Hollywood media portrayals also frequently depict trans lives as tragic, doomed, and/or pathological. Instead of portraying the very real dangers of being trans in our world or making trans women the punchline of a joke, Her Story makes the revolutionary gesture of celebrating trans women’s triumph, joy, and love. This gesture to celebrate trans women’s love stories, while revolutionary in its break with traditions of trans representations, also breaks away from the idea that trans representations must be politically driven. When Allie first approaches Violet about the interview, Violet instantly responds that she’s not an activist, assuming that Allie would only be interested in a trans story that deals with political work. Violet’s assumption points to the way that dominant culture tends to mark trans women as ‘important’ or ‘significant’ when they discuss political trans issues. The notion that trans people need to prove their value or justify taking up space undergirds media representations that only focus on trans people’s activist contributions to the queer community. So, perhaps, a rom-com love story does, after all, constitute revolutionary trans representation.

Media Platforms and Radical Representation

Queer scholars have for decades debated the question of what makes representation radical. Is it a matter of form? Of content? Of audience reception and reading practices? While we could look in many places for a media’s radical potential, I suggest here that we look to the media object’s effects, what it produces. The success of a series like Pose, while groundbreaking in its critical acclaim, confirms the idea that in order for trans stories to make it to television screens, there must be a successful cis producer willing to back the project. Pose’s success relied on Ryan Murphy’s established name and reputation. The show’s critical acclaim, however, involves more than Murphy’s name alone. Critics’ positive reception of Pose tends to emphasise its significance as a historical document, and praises the way the series tackles AIDS crisis history. [16] Pose’s success further demonstrates how trans representation often receives widespread critical attention and viewership when it tackles political and/or historical concerns. Without the justification of history and politics, Pose would likely not have received the same popular and critical reception that it did. More specifically, we must ask whether audiences and networks would think a show about trans and queer communities of colour is worthwhile television were it not set in an AIDS crisis past.

Pose might offer certain types of trans representations, but we must also ask what type of trans representations it does not present. When critics and audiences praise these mainstream series for its representation of a trans past (specifically trans of colour), what does that say about the possibilities of trans representations set in the present? The historical pedagogy of Pose teaches audiences about a past they likely know very little about, but it also teaches audiences that trans representations must be explicitly historical and/or political in order to be seen. If we only conceive of radical trans representation as that which confronts trans political issues, we might actually reinforce the normalising assumption that trans people are not ‘normal.’ In other words, politically-motivated trans representation might ultimately have the normalising effect of keeping trans people out of the space of ‘the normal’ by keeping them in the space of ‘the political.’ By refusing trans people the types of romance, comedy, and sitcom narratives reserved for cis characters’ storylines, seemingly ‘radical’ trans representations deny the possibility of representing a full range of trans experience.

Over the last two decades, major television networks have debuted more and more series focused on gay and lesbian characters’ friendships, romances, and daily struggles. Beginning with Will & Grace’s (1998- ) breakout success, series focused on gay characters have found their way into the homes of Middle America. Does an audience exist for a trans equivalent of Looking (Michael Lannan and Andrew Haigh, 2014-2015), The L Word, and Queer as Folk (Ron Cowen and Daniel Lipman, 2000-2005)? [17] Or, are networks willing to invest in that audience? My framing of Her Story, here, creates a tension between the possibilities provided by YouTube’s independent (and user modified) streaming platform and media creators’ aspirations to network television screens that have historically perpetuated negative stereotypes of trans women, if they have not entirely ignored trans women’s existence. I do not claim to resolve that tension, but rather, I want to push at how we understand diversity in media with regard to different media platforms. One of the utopian visions of the digital is diversity of information—anyone can find anything they are looking for with the click of a mouse. Yet, if trans media content can only be found through very specific YouTube searches, it remains unlikely that viewers outside of trans and/or queer communities will ever encounter trans media. If mainstream audiences (cis, hetero, white, and/or male viewers) never see series like Her Story, its revolutionary power is stopped short.

In his conversation with Alex Juhasz, trans filmmaker Sam Feder explains his dissatisfaction with mainstream media,

At some point I stopped experiencing the joy of mainstream films and TV because I found most of it so offensive. So I stopped watching. Every other joke is homophobic, racist, sexist, transphobic, you name it! Why can’t mainstream comedy be more clever than that? This representational history is what most marginalised groups face. (Feder & Juhasz 2016)

The documentary Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen (2020), directed by Feder and produced by Cox, comprehensively demonstrates how mainstream cinema has degraded and mocked trans individuals since its silent-era origins. However, Disclosure never looks outside of mainstream media in its discussion of trans representation. While Richards and Ross are both featured as talking heads, their work on Her Story is never discussed. Her Story only appears in a blink-and-you-miss-it clip as part a montage of contemporary trans representations. The shot shown comes from a scene with Paige and one of her clients, a trans woman suing a women’s shelter for kicking her out because she is trans. Rather than highlight the groundbreaking storylines Ross portrays in Her Story, Disclosure only discusses Ross’ role on Pose. Ross’ Pose character, Candy, is killed by a John and found in a closet—yet, the film privileges this role on Pose presumably because of the series’ critical attention and popularity. In order for revolutionary web series like Her Story to receive the attention they deserve, we cannot continue to treat network television series as the only ones that matter.

Many of Her Story’s contemporaries have gone on to secure slots on network channels, such as HBO’s Insecure (Issa Rae, 2016- ), which started as a web series called Awkward Black Girl (2011), and Brown Girls (Fatimah Asghar), which started as a 2017 web series by the same name. [18] While audience and critical attention to Awkward Black Girl and Brown Girls has led to their place in HBO—the quality television mecca—Her Story has not had the same luck. Richards stated that the production team prepared treatments for 10 half-hour episodes, but despite the series’ Emmy nomination and critical acclaim as a revolutionary media project, not a single major network has made a move to acquire Her Story’s (Brighe 2016). Advocate claimed in 2016 that Richards’ series ‘could change everything,’ but why, years later, is that still not the case (Brighe 2016)? Even now, in a supposed revolutionary media moment when women, queer people, and people of colour are being featured more than ever in pop culture, trans stories told by trans writers remain absent from mainstream screens. The revolutionary potential of Her Story and its failure to become mainstream, demands that we, as media scholars and media consumers, investigate the persistent blinds spots of diverse media representation, to ask which stories we have not heard. It is not enough that we praise a series like Her Story for its potential; we must also be willing to investigate where we continue to fail as consumers of media.

Notes

[1] The series also won the 2016 Gotham Independent Film Award for Breakthrough Series—Short Form and a Special Recognition award at the 2017 GLAAD Media Awards.

[2] See Mareike Jenner.

[3] Her Story played at LA Film Festival, Melbourne WebFest, and Seattle WebFest, as well as NYC’s NewFest and LA’s OutFest, two of the largest queer film festivals in the US.

[4] See Vincent Terrace.

[5] Barbelle follows an on-again, off-again lesbian pop duo, and it recently released its second season on YouTube.

[6] See Raquel Willis.

[7] It is of course worth noting that Ryan Murphy has brought on Janet Mock to write seven episodes and direct three. Pose represents a strong step forward in trans folks’ involvement in the production of network television.

[8] The effect of authenticity I describe here comes directly out of Roland Barthes’ theorization of the reality effect.

[9] TERF emerged alongside trans women’s growing visibility during the 1970s, coinciding with the women’s movement and gay liberation. Germaine Greer and Janice Raymond were two of the founding figures of these sentiments. Raymond’s book provides the first thorough account of some radical feminists desire to exclude trans women from women’s spaces. Germaine Greer has more recently (and very publicly) asserted her belief that trans women are not women.

[10] I use partner as a sort of provisional term for Mark, as I am not sure how to best label his relationship with Violet. Violet explains their dynamic late in the series, detailing how her relationship with Mark began as an escort-client one, but turned into something else when he invited her to live with him out in LA and in exchange for the promise that Violet would get sober.

[11] The crowdfunding campaign for Her Story raised approximately $40,000 from over 600 different donors, which largely helped cover the cost of post-production labor.

[12] Richards currently has 43.4K followers on Twitter, while costars Ross and Zak have 64.4K and 8.4K, respectively.

[13] See Julia Serano for more on gendering and cis-privilege.

[14] Ramin Setoodeh hosted a roundtable of trans actors to respond to the Scarlet Johansson Rub and Tug controversy, in addition to sparking conversation around the increase in trans representation with actresses like Laverne Cox. The roundtable included Jen Richards, Lavern Cox, Chaz Bono, Trace Lysette, Alexandra Billings, and Brian Michael.

[15] HIV/AIDS activist Alex Juhasz’s and trans filmmaker Sam Feder’s (2016) conversation in Jump Cut reminds readers that visibility alone does not lead to progress. Too often, trans women are used to creating a certain type of tragedy porn, a porn in which cis audiences are able to voyeuristically consume trans women’s excessive suffering.

[16] See Caroline Framke.

[17] We might also consider The L Word: Generation Q here.

[18] Illana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson’s Broad City, which began as a web series, debuted on Comedy Central in 2014. Ingrid Jungermann’s web series F to 7th is also under production as a half-hour comedy at Showtime.

REFERENCES

Barthes, Roland (1989), ‘The Reality Effect’, in Richard Howard (trans.), François Wahl (ed.), The Rustle of Language, Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 141-148.

Brighe, Mari (2016), ‘The Emmy-Nominated Trans Web Series Her Story Could Change Everything,’ Advocate, July 31, 2016, https://www.advocate.com/transgender/2016/7/31/emmy-nominated-trans-web-series-her-story-could-change-everything (last accessed 30 November 2019).

Feder, Sam & Alex Juhasz (2016), ‘Does Visibility Equal Progress? A Conversation on Trans-activist Media’, Jump Cut No. 57, https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc57.2016/-Feder-JuhaszTransActivism/text.html (last accessed 30 November 2019).

Film Independent (2016), ‘Trans web series ‘Her Story’: 2016 Film Independent Forum’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LiwkisBJzcY (last accessed 1 December 2019).

Framke, Caroline (2019), ‘Pose Season 2: Diving Deeper Into One of LGBTQ History’s Darkest Chapters,’ Variety, 6 June 2019, https://variety.com/2019/tv/news/pose-season-2-preview-ryan-murphy-1203232474/ (last accessed 26 October 2019).

Greer, Germaine (2000), The Whole Woman, New York: First Anchor Books.

Horak, Laura (2014), ‘Trans on YouTube: Intimacy, Visibility, Temporality,’ Transgender Studies Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 572-585.

Horak, Laura (2018), ‘Trans Studies,’ Feminist Media Histories, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 201-206.

Jenner, Marieke (2017), ‘Binge-watching: Video-on-demand, Quality TV and Mainstreaming Fandom’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 304-320.

Matz, Courtney (2016), ‘Her Story: How a Web Series Can Save Lives,’ Film Independent, 2 November 2016, https://www.filmindependent.org/blog/story-web-series-can-save-lives/ (last accessed 17 October 2019).

Raymond, Janice (1979), The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, Boston: Beacon Books.

Serano, Julia (2007), Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, New York: Seal Press.

Setoodeh, Ramin (2018) ‘Transgender Actors Roundtable: Laverne Cox, Chaz Bono and More on Hollywood Discrimination,’ Variety, https://variety.com/2018/film/features/transgender-roundtable-hollywood-trump-laverne-cox-trace-lysette-1202896142/ (last accessed 25 November 2019).

Terrace, Vincent (2015), Internet Lesbian and Gay Television Series, 1996-2014, Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

Willis, Raquel (2015), ‘4 Trans Web Series You Have to Watch This Fall,’ Pride, https://www.pride.com/transgender/2015/9/19/4-trans-web-series-you-have-watch-fall (last accessed 18 December 2019).

Films & TV Series

#Hashtag (2013-2015), created by Caitlin Bergh (2 seasons).

20 Sum-Thing (2019- ), created by Hannah Stockman (1 season).

Albert Nobbs (2011), dir. Rodrigo García.

The Mis-Adventures of Awkward Black Girl (2011-2013), created by Issa Rae (2 seasons).

Barbelle (2017- ), created by Gwenlyn Cumyn & Karen Knox (2 seasons).

Bernice Procura (2018), dir. Allan Fiterman.

Boys Don’t Cry (1999), dir. Kimberly Peirce.

Broad City (2014- ), created by Illana Glazer & Abbi Jacobson (5 seasons).

Brothers (2014- ), created by Emmett Lundberg (2 seasons).

Brown Girls (2017), created by Fatimah Asghar (1 season).

Carmilla (2014-2016), created by Jordan Hall & Ellen Simpson (3 seasons).

Dallas Buyers Club (2013), dir. Jean-Marc Vallée.

Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen (2020), dir. Sam Feder.

Eden’s Garden (2015), created by Seven King (1 season).

Euphoria (2019- ), created by Sam Levinson (1 season).

Good Trouble (2019- ), created by Joanna Johnson (2 seasons).

Her Story (2016), created by Jen Richards (1 season).

Insecure (2016- ), created by Issa Rae (3 seasons).

Looking (2014-2015), created by Michael Lannan & Andrew Haigh (2 seasons).

Mrs. Fletcher (2019), created by Tom Perrotta (1 season).

Pose (2018- ), created by Ryan Murphy & Steven Canals (2 seasons).

Queer as Folk (2000-2005), created by Ron Cowen & Daniel Lipman (5 seasons).

The Carmilla Movie (2017), dir. Spencer Maybee.

The Crying Game (1992), dir. Neil Jordan.

The Danish Girl (2015), dir. Tom Hooper.

The L Word (2004-2009), created by Ilene Chaiken (6 seasons)

The L Word: Generation Q (2019- ), created by Ilene Chaiken (1 season).

Transparent (2014-2019), created by Jill Soloway (5 seasons).

Will & Grace (1998- ),created by David Kohan & Max Mutchnick (11 seasons).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey