Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: The Subversive Role of Music and Sound in Le bonheur & Cléo de 5 à 7

by: Natasha Farrell , November 7, 2023

by: Natasha Farrell , November 7, 2023

Le bonheur, c’est d’accepter la contradiction.(Happiness is acceptance of contradiction). [1] (Varda 1994: 70)

*

The interworkings of sight and sound in Agnès Varda’s early work are the focus of this essay, especially from the perspective of the filmmaker’s subversive cinematic representation of how signifying social and cultural modes construct our ‘reality.’ With reference to Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965) —her third, and probably most misunderstood and certainly most critically disputed feature film—and Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962), I argue that Varda explores dissonance between image, music, and sound to interrogate patriarchal constructs. By privileging viewer engagement over viewer identification, Varda reveals the contradictions at the heart of ideal femininity and the post-war nuclear family as a true innovator and dismantler of the patriarchy through cinematic means.

Speaking to Cahiers du cinéma in 1977, Varda spoke of the contrasting structural dialectics that manifest throughout her work: ‘All my films are constructed out of such a contradiction-juxtaposition. Cléo: objective time/subjective time. Le Bonheur: sugar and poison. Lions Love: historical truth and lies (television)/collective mythomania and truth (Hollywood)’ (2014: 85). [2] The intentional incongruity resulting from the visual and thematic binaries that shape Varda’s filmmaking is of course emblematic of the cinematographic strategies of her New Wave generation. However, Varda’s soundtrack also significantly contributes to the rich juxtapositions that she crafts in her films. Her films rely on an abundance of diegetic and non-diegetic music, voices of characters, dialogues, and diverse everyday sounds to explore the disquieting boundary where fiction and documentary—the illusion and the real—overlap and dialectically interact with each other. Varda was very much aware of the relationship between image and sound to shape perception in cinema: ‘Images, sound, whatever, are what we use to construct a way which is cinema, which is supposed to produce effects, not only in our eyes and ears, but in our “mental” movie theatre in which image and sound already are there’ (1986: 132). This is an aspect of her oeuvre which remains little explored and underappreciated. Claudia Gorbman’s work is a substantial first step in redressing this omission. As Gorbman notes ‘music is very often a structuring element in Varda’s filmmaking, but only rarely is it described as such by those who write about her work’ (2008: 27). [3] This essay seeks to fill this gap by exploring the subversive ways in which Varda’s soundtracks in Le bonheur and Cléo from 5 to 7 shape the viewer’s perceptions.

I ground my analysis in theory which affirms the feminist critique in the filmmaker’s early films ‘through their critical explorations of both the production of femininity and their representations, yet they are often not understood as such’ (Flitterman-Lewis 1996: 215). Focusing on a reading of film that postulates sound as central to inquiries of the entire sound-image, I frame my investigation using French theorist and musicologist Michel Chion’s approach. In Audio-vision, Chion explores the way in which images and sounds influence each other and underlines the multiplicity of possible effects generated by this relationship. Within Chion’s argument is his theory of reciprocity between sound and image: the two are interrelated and one cannot act on the other without being itself altered. The audio-visual world is consequently designated by Chion as ‘a contract,’ giving rise to a specific perception called ‘audio-vision’ (2021: 5). Employing the term ‘added value’ (2021: 13) to elucidate how sound and image transform each other in the viewer’s perception, Chion asserts that the effects of these two combined elements are more powerful than either could be on its own. Hence, ‘sound enriches a given image so as to create the definite impression … that this information or expression “naturally” comes from what is seen, and is already contained in the image itself’ (2021: 13-14).

Insisting on the role and place of music to question patriarchal structures in the two films, I will also consider and seek to remedy some of the critical misunderstandings and doubts surrounding Varda’s use of music in Le bonheur, of which Gorbman writes that: ‘the almost perfect ambiguity of Le bonheur and the debates to which this film gave rise may well derive from the difficulty the audience has (whether consciously or not) in assigning the music to one “side” or the “other” … an emanation of the hero or a commentary on him’ (2008: 31-32). My argument is therefore that, by presenting a transgressive depiction of the male protagonist’s perception of happiness, Varda’s intent was to achieve a contradictory evocation. The first part of this essay explicates the filmmaker’s usage of music in counterpoint and the effects of its repetitions. I contend that the musical scores in Le bonheur and Cléo de 5 à 7 are employed as subversive devices to spotlight the awareness of female subjectivity. In the last section, I turn to a comparative analysis of Varda’s explorations with voices of characters and dialogues in order to elucidate connections between her second and third films as the soundtrack pertains to representations of the feminine ideal: the pretty blonde. Illustrating one of her favourite motifs—which she evoked in her own text Varda par Agnès: ‘le bonheur, c’est d’accepter la contradiction’ (happiness is acceptance of contradiction) (1994: 70)—the relationship between image, sound, and music itself in Varda’s cinema is an opening which provokes the spectator to reflect on issues of gender, power, and identity.

‘I listened to Mozart, I Thought of Death’s Preponderance:’ Investigating Varda’s Idea of Contradiction and Musical Counterpoint in Le bonheur.

Le bonheur’s apparent focus on protagonist François’ (Jean-Claude Drouot) pursuit of marital bliss initially proved disconcerting to critics. Varda presents the female protagonists Thérèse (Claire Drouot) and Émilie (Marie-France Boyer) as mirror images of each other within a background of adultery, death, and suicide that does not appear to disrupt François’ bucolic domestic life. In the film’s denouement, Varda returns to the image of the happy family with Émilie succeeding Thérèse in the role of wife and mother. As a result, Le bonheur was either long neglected in scholarship (Bénézet 2014: 10) [4] or dismissed as more ‘feminine than feminist’ (Tigoulet 1991: 57-70). [5]

Prominent scholars such as Sandy Flitterman-Lewis have re-oriented understandings of the film as ‘profoundly feminist in its concerns’ (1996: 232). Varda, she continues, ‘produces an analytic view of the functions of the bourgeois housewife, of patriarchal dominance … and casts these all in the light of feminist critical evaluation’ (1996: 233-234). Of late, Heidi Holst-Knudsen (2018: 504-526), Susan Felleman (2021: 17-34), Rebecca DeRoo (2008: 189-209) and Amy Taubin (2008) have focused attention on Varda’s intermedial explorations critiquing the limitations and frustrations on women in Western modern culture. Flitterman-Lewis and Holst-Knudsen (2018: 506) both contend that the film’s complex visual aesthetic introduces a distancing effect ‘that highlights certain elements while leaving the spectator in the productive position of forming his or her own conclusions’ (Flitterman-Lewis 1996: 234). Despite these enlightened interpretations, the film continues to inspire critical debates. Furthermore, music and sound are rarely awarded their thematic and structural importance in Le bonheur’s ironic evocation of heteronormative domestic clichés which are ultimately shown to be more sinister than they appear.

Le bonheur famously opens on a shot of a sunflower, scored to a woodwind performance (orchestrated by Jean-Michel Defaye) of the fugue section of Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue in C minor, K.546. Mirroring the contrapuntal nature of the piece’s minor mode, the cutting back and forth between this languid flower and its blossoming counterparts at first reads as playful (Fig. 1). However, as the sharp quality of the woodwinds and the speed of the cuts increase, the effect conveys death, symbol of all the vibrancy lost; and in that juxtaposition between sound and image lies interpretive keys to the entire film. It is my contention that music is central to the inherent contradiction of the film—sugar and poison—which Varda is carefully crafting. Commenting on the soundtrack (both the fugue and the film’s other non-diegetic music source Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet in A major, K.581) Varda notes not only its quality of anguish but also their duality when she says: ‘J’ai écouté Mozart, et je pensais à la mort qui est au milieu des choses’ (I listened to Mozart, I thought of death’s preponderance) (1998). [6] Playing on viewers’ expectations of Mozart’s lilting tones, the film score is key to the construction of the film’s binaries because it reveals itself—despite all its apparent cheeriness—to be dark and twisted.

Fig. 1: The structural and thematic dominance of Mozart in Le bonheur (1965).

Fig. 1: The structural and thematic dominance of Mozart in Le bonheur (1965).

The filmmaker emphasised this ambiguity in a 1965 interview with Cahiers du cinéma when stating that her idea for Le bonheur started with family photos: ‘When you look more closely, you get an uneasy feeling. … The appearance of happiness is also a form of happiness’ (2014: 31). What Varda appears to be deconstructing is the myth of the French post-war nuclear family perpetuated by politicians and popular media as symbolising a ‘form of happiness.’ In a film that is shot like a fairy tale, a postcard, or an advertisement, the music’s dominant and insistent presence transposes cinematically that same sense of unsettling discord to provoke the viewer’s deliberation on situations that the ‘happy’ protagonists ignore.

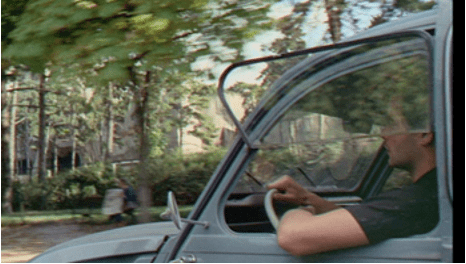

Consider the reprise of Mozart’s Fugue in C minor in the film’s montage sequence. Scored over images of Thérèse’s hands in close-up performing domestic tasks and with the children, the music is interwoven with sounds of the quotidian and nature. These shots cut to François locking the family door, and then in the van on his way to Vincennes. The latter jump-cuts to a series of images including ‘la porte dorée’ (the Golden Door) and a group of lions and birds at the zoo, before intercutting to the first shot of beautiful postal worker Émilie. Paralleling, and thereby contrasting with, the idyllic family picnics that Varda scores to Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet and long cuts that she favours at the beginning of the film, the shifts from the intrinsic sweetness of the clarinets to sections of the fugue have a clear rhythmic tie in with Varda’s choppier editing choices. Contrary to Dave Kehr’s assertion—in his review of the Criterion Collection’s 2008 DVD re-release of the film—that the film offers no clues as to whether it should be qualified ‘as either the most drippingly sentimental film ever made or the most dryly ironic’ (Kehr 2008: 5), Le bonheur is a deftly sustained cognitive dissonance exploration to subvert patriarchal structures.

In his texts such as Music in Cinema, Michel Chion is interested in the interrelationship between the character of a music and the purpose of an image, when the music seems to contradict what the spectator sees on the screen. Chion terms this effect, which ‘seems to exhibit conspicuous indifference to what is going on in the film’s plot, creating a strong sense of the tragic,’ ‘anempathetic music’ (2019: 244). While anempathetic music relies not on ‘distanciation but rather of tenfold emotion’ (Chion 2019: 244-45), the effect produced by the apparent disconnect between sound and image can also be in extreme cases a ‘contrapuntal didactic’ (1985: 124). The distinction outlined by Chion is that the latter breaks the identification process and calls for an intellectual stance (1985: 134), forcing the spectator to adopt a very distanced, or even critical, position in relation to the characters (as for example a happy tune that accompanies a tragic event). Varda’s play of variations and oppositions with the film’s non-diegetic Mozart pieces functions as a ‘contrapuntal didactic.’ The synthetic ‘warmth’ of the images and Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet counterposed against the darker rhythms of Mozart’s fugue and adagio each draw, to paraphrase Chion, a special charge from the other and alerts the viewer to the film’s implicit feminist critique. Le bonheur is perhaps Varda at her most confrontational, precisely because its sun dappled Edenic vision appears so pleasant on the surface. This is a world that operates around François’ whims. Everything, from the women who love him to the beautiful gardens he walks through, bends visually to the male protagonist. In Varda’s words, if the film hinges on ‘showing the clichés’ (2014: 55) of this too-perfect world, the contrapuntal nature of the music acts as an important signpost or audio-vision. Recalling the literary device of the unreliable narrator, Varda’s use of music in ‘didactic counterpoint’ engages the viewer to come to their own conclusions because it accentuates that he is a biased source of information.

Via the intermediary of the Mozart soundtrack, Varda performs a high-wire enactment of the fallacies of male privilege. Gorbman notes that one of the contradictions that arises in Le bonheur (a film essentially about denying the existence of conflict) stems from the audience’s uncertainty of how to read the Mozart music as either firmly planted in François’ imagination and conveying his perspective or objective (2008: 33). In some interviews, Varda offers insight into her complex strategy which supports a reading of the characters as unreliable and pure acidic satire. The film, Varda affirms, ‘is not a psychological portrayal of an egotistical man torn between two blondes. Rather, it’s an extremely detailed almost maniacal exposé in images and clichés of a certain kind of happiness’ (2014: 75). The juxtapositions of music and image crafted by Varda never exists in the actual, but only in the conceptual or symbolic Edenic space constructed by the film. Part of the shock of Le bonheur is the self-conscious dream world in which this cruelty occurs. There is no one to condemn François for his charmed life. Only we, the audience, can submit an objection. In the studied montage sequence, the give and take between the imperturbable and austere quality of Mozart’s fugue and the brightly coloured images transforms the perception of the other. The music ‘adds value,’ to borrow Chion’s expression, and imports such strong irony as to be clearly perceived as a commentary on François.

Further signalling viewer perception of the contradictions, both structural and cinematographic, is the device of repetition. Varda returns in the montage to shots of Thérèse confined to the home, bent to repetitive tasks. Yet, sounds of Thérèse’s sewing machine are eclipsed and adhere to the score’s syncopation. Through these subtle clues—the didactic counterpoint, and the effect of repetition—the film score calls attention not only to the façade of the male protagonist’s saccharine disposition, but also to myths about femininity and expectations of women in this era. The diegetic sound of the van’s motor juxtaposed with Mozart and imagery of the roaring lions confirms Varda’s subversive intent here to critique post-war heteropatriarchal values and a housewife’s role as an instrument in a biased social structure. The jump cut from the squawking birds to Émilie likewise conveys the leonine entitlement implicit in Francois’ worldview and foresees his pursuit of her (Figs. 2-3). Therefore, by presenting a hyperbolic pageantry of male happiness to its absurd extreme, the filmmaker’s intention is to denounce patriarchal hegemony.

Figs. 2 & 3: Dismantling the patriarchy through the intermediary of the soundtrack (Le bonheur, 1965).

Figs. 2 & 3: Dismantling the patriarchy through the intermediary of the soundtrack (Le bonheur, 1965).

Further illustrative of music’s role in the construction of the film’s satire are Varda’s pointed exaggerations and selective overamplification of the soundtrack. In a subsequent scene in which François runs to Émilie’s apartment, the performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet attenuates any audible real street sound. For Chion, sound and image create the ‘definite impression’ that the cinematic experience ‘naturally’ comes from what is seen, ‘and is already contained in the image itself’ (2021: 5). This ‘added value,’ he continues, ‘is what gives the (eminently incorrect) impression that sound is unnecessary, that sound merely duplicates a meaning which in reality it brings about’ (2021: 13-14). Therefore, the over-recording and cloying sweetness of the music undermines the protagonist because it roots both the character and his blasé happiness in artifice. Punctuating his skips and hops around a street post and as he leaps into the air, the music is reminiscent of a Gene Kelly musical such as Singin’ in the Rain (1952). Rather than promoting a male fantasy, Varda’s scoring of the scene reads like a caricature of Hollywood cinema (Fig. 4). While reinforcing the idea that François’ worldview is untrustworthy and his bliss, then, is a shallow one, the filmmaker’s explorations with sound restructure audience expectations of how screen images should be perceived. As Flitterman-Lewis states, ‘in exaggerating the conventions of both the melodrama and the musical, … Varda produces in Le bonheur a level of formal critique of commercial narrative cinema, just as certainly as she challenges patriarchal social relations’ (1996: 234). The filmmaker’s satirical intertexts to 1950’s Hollywood [Production Code-era] happy endings contribute to the argument that Le bonheur works as a social critique of media and deconstructs filmic myths.

Fig. 4: Mozart as a vantage point to parody classical Hollywood cinema (Le bonheur, 1965).

Fig. 4: Mozart as a vantage point to parody classical Hollywood cinema (Le bonheur, 1965).

The choice of Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue in C minor, K.546 is another significant marker of the juxtapositions between music and image to critique clichés of heteronormative structures, especially as it pertains to representations of the female characters Thérèse and Émilie. Importantly, Mozart’s K.546 went through a significant transition as the fugue element was composed five years earlier than the adagio, and later reworked and then recontextualised into the finished string quartet (Keefe 2017: 454-462). Although the rationale for Mozart’s return to his earlier fugue is unclear, the composer (influenced by Bach and Handel) embraces counterpoint at once more complex than was common in his earlier works. The revised fugue in Mozart’s Adagio is made up of alternating sections and introduces a similar dualism: ‘It is a strict, four-voiced fugue, with a deeply serious, “dualistic” theme, … and it contains all the devices of inversion’ (Einstein 1962: 273). [7] The themes of musical inversion and counterpoint parallel Le bonheur’s structural, thematic, and cinematographic aesthetics in which the ideal nuclear family is changed, reconstituted, and restored. Scored to sections of K.546, the film begins at the height of summer with images of the happy family and ends in autumn with the replication of the dead, drowned Thérèse by Émilie. The dualism in the darker Mozart chamber work—a transcription for strings of the melodic themes of the original piece—is an ironic musical metaphor of the interchangeability of women in the film. DeRoo has noted the structural link between the two women through the visual mirroring of their performance of identical domestic tasks (2008: 203). This structural and thematic link is also established through the music which strengthens the analogy in the parallel sequence towards the end.

The resemblance between the two female characters is exacerbated by Varda’s choice to cast near-identical blonde women as Thérèse and Émilie, which is a mordantly ironic condemnation of women as expendable and their role as guarantors of male privilege. Referencing the characters’ resemblance in her own monograph, Varda writes: ‘elles se ressemblent, elles ont presque les mêmes gestes. L’idée d’adultère se transforme en celle de glissement’ (they look like each other, they have almost the same gestures. The idea of adultery becomes a gliding movement) (1994: 67). Viewer perception of this cinematic ‘glissement,’ is further oriented by a diegetic traditional waltz which accompanies the street-dancing scene. Varda hints at its importance with a percussive drum roll that punctuates the cut from an establishing shot of dancing couples to a medium shot of François and Thérèse. Guided by the incessant rhythms of the music (the sweet main melody builds to the drumbeat), the beautiful blondes Thérèse and Émilie pass successively into François’ arms as if they suddenly became indistinguishable, mirroring each other in a dizzying game reminiscent of Hitchcock (Figs. 5-6). As David Schroeder affirms, Hitchcock’s association of the waltz to ideas of ‘chaos and disorder,’ ‘as it does in [Maurice] Ravel’s work,’ is influenced by German cinema (2012: 80). Representative of sexuality, also lasciviousness or a ‘dance of death,’ the waltz, explains Schroeder, was viewed by some Viennese writers as a mechanism ‘to avoid dealing with reality’ (2012: 77-78). The effect of Le bonheur’s waltz implies a play on these contradictions. The structural variables in the scene contrast sharply with the bouncy tune—oppositions such as public/ private joy, fleeting happiness and the apparently stable—ultimately symbolising transitoriness. Therefore, the waltz functions as an unsettling reminder of the ‘sugar and poison’ in this candy-coloured Eden. Coupled with the history of transition and musical inversion of Mozart’s K.546, the music offers a perfect attack by Varda upon societal ambivalence towards criticism of the patriarchy itself.

Figs. 5 & 6: The waltz, myths of domestic bliss and twin images of Thérèse and Émilie, reminiscent of the Hitchcock blonde (Le bonheur, 1965).

Figs. 5 & 6: The waltz, myths of domestic bliss and twin images of Thérèse and Émilie, reminiscent of the Hitchcock blonde (Le bonheur, 1965).

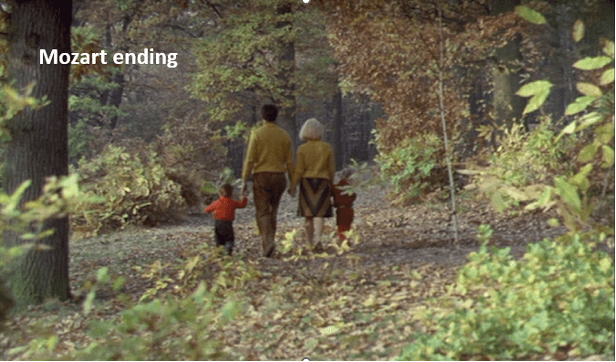

Le bonheur’s final sequence strikes a further dissonant note in the ‘happy ending’ distancing the film from everything—the nuclear family naturalised and eternalised by its pastoral surroundings—which critics like Johnston ([1973] 2006: 31-40) accused Varda of reproducing uncritically. The brightness and charm of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet gives way to the darker Adagio and Fugue in C Minor. Orchestrated with more menacing-sounding strings, Varda plays on variations in Mozart’s music (adagio/ fugue and strings/ woodwind) and the dialectics in the film’s circular narrative to critique the Edenic portrayal of the nuclear family. Paralleling Mozart’s music that is both changed yet unchanged, the persistently untroubled François is back to inhabiting a postcard vision of family life. But Thérèse—who supplemented the family income by working as a dressmaker—is dead, and Émilie, the young woman with her own apartment and job outside the domestic sphere, has lost her agency. With cinema, Chion affirms, ‘sound shows us the image differently than what the image shows alone’ (2021: 21). The combined effect of the score, device of repetition, and shot of mist emanating from François’ lips transpose the presence of death referenced by the filmmaker in interviews. Varda is at her most darkly ironic here, challenging expectations of Mozart’s music and autumn visuals which typically convey warmth and safety. The music orients the viewer to reject the image: to perceive it for what it really is—a fractured fairy tale. As the string’s crescendo builds, the smiling François, Émilie, and the children join hands, family bliss receding in the fadeout, the film’s oppositions between music and image function like a horror film (Fig. 7). By bringing into play the ironic reflection of the musical inversion, dualism, and history of transition in Mozart’s piece, the repetitions and oppositions in the Adagio and Fugue in C minor are thus central to the film’s deconstruction of the harmonious veneer of the post-war family, or as Varda puts it, ‘une pêche de plein été avec ses couleurs parfaites, et dedans il y a un ver’ (a summer peach with its perfect colours, and inside there is a worm) (Varda 1998).

Fig. 7: Deconstructing the image of the happy family (Le bonheur, 1965).

Fig. 7: Deconstructing the image of the happy family (Le bonheur, 1965).

‘Refusing to be This Cliché’: Subversive Effects of Cléo de 5 à 7’s Musical Score.

Paralleling the studied explorations with Mozart, Cléo de 5 à 7’s music illuminates the motif of contradiction—‘between the clichés of our mental life and the images of lived life’—which Varda states ‘is really the subject of all of my films’ (2014: 74). She uses diegetic and non-diegetic music contrapuntal to the image to critique entrenched gender stereotypes embodied by the film’s titular protagonist: a beautiful and popular blonde singer (Corinne Marchand) and her growth from a passive to an active woman as she waits for life-threatening biopsy test results. Varda eloquently explains that ‘Cléo is a woman-cliché, tall, beautiful, curvaceous. So, the entire dynamics of the film centres on the moment this woman refuses to be this cliché, on the moment when she no longer wants to be looked at but wants instead to look at others’ (2014: 73). While the viewer can perceive Cléo’s emotions by what is seen on the screen, insight into her fractured psychology is oriented and driven by the soundtrack.

Varda’s celebrated catalyst for the protagonist’s transformation is a musical scene which sends Cléo into investigation of her ideal beauty and her relationship to other people as much as it does with cancer itself. Cléo begins to sing ‘Without you’ (also known as the ‘Cri d’amour’ or ‘Cry of Love’), co-written by Varda and acclaimed film composer and frequent Jacques Demy collaborator Michel Legrand. [8] Juxtaposing the everyday and the surreal, the private and public performance contexts, Varda’s camera circles until the song’s third verse, where it stops. Shot in close-up, her framing allows Cléo to sing directly to the audience. Chion calls these effects ‘empathetic’ whereby the music reinforces or seems to adhere directly to the feelings generated by the scene, in particular the feeling that is supposedly felt by certain characters (2019: 244). At this point a black backdrop emerges behind Cléo and nondiegetic music, a string orchestra or ‘pit music,’ can be heard as the song shifts gears from the universal romanticism of a love ballad to existential lament about body horror and the terror of death: its despair- and decay-filled lyrics ‘seule, laide et livide’ (alone, ugly, and ashen) written by Varda herself. As she sings about her body being ravaged by despair, Cléo loses herself in the music, or as Gorbman eloquently describes, ‘she is the music’ (2008: 29). Since those around her on screen dismiss her fears, she turns to the viewer, in desperation, for understanding.

Contrary to Gorbman’s claim, with the juxtaposition of the Legrand/ Varda score, that ‘if “La Belle P.” is a song affirming life, the “Cry of Love” might be a summons to death’ (2008: 28), it is my contention that Varda’s usage of empathetic and anempathetic musical effects fulfils different and specific subversive effects. Operating as Cléo’s hit song within the narrative, ‘La Belle P. (La Belle Putain)’ which can translate to ‘The Flirtatious Whore,’ underscores the sexualised trope of the gold-digger whilst also representing Cléo’s celebrity status as a popular and coveted singer in Paris. Like her beauty, Cléo’s music and commercial value become fleeting commodities in the face of potential death. Varda engages with ‘La Belle P.’ as a device to challenge the incongruities of femininity: playing on viewer’s perceptions of Cléo’s apparent superficiality as an agency-less dolly, she interweaves the jazzy pop song—with its objectifying title and lyrics—throughout the film to highlight Cléo’s rich subjectivity.

The viewer first hears the recording of ‘La Belle P.’ in the film’s taxi scene as it plays diegetically on the radio. Illustrative of Chion’s concept of reciprocity between sound and image, how sounds can fill in gaps in the audience’s perception, Cléo’s ensuing dialogue (‘C’est mauvais! Ce disque est une trahison. Pourquoi ne pas refaire.’ (It’s awful! This recording is awful. They must do it again) and her visible embarrassment at the song construe her relationship to her musical output as actively self-critical. Varda also employs a voice-off outside Cléo’s window who declares that ‘you don’t often hear that song.’ This further orients understanding of the protagonist’s conflicted self-image. She will be discarded, disposable like the bouncy music.

Structurally paralleling with the taxi scene is the subsequent café Dôme scene. Symbolic of her growing agency, it is now Cléo who plays ‘La Belle P.’ on the jukebox. As she assesses her popularity and the song’s ephemerality, Cléo glides through the café to the disinterest of the patrons, hearing snippets of conversations about conflict (references to the Algerian War, to surrealism, to Picasso). The soundtrack’s opposition between the happy music and cacophony of chatter attaches its ‘indifference’ to the image, to borrow Chion’s expression (2019: 245). Foreshadowing the device of repetition in Le bonheur’s Mozart film score, the recurrent anempathetic music serves as a transposition of the female protagonist’s ‘new way of seeing the world’ (2014: 19). The subversive element is that Cléo’s interest is not on herself (she asks the taxi-driver to turn off the radio), or her beauty (she rebuffs a man’s offer to buy her a drink). Instead, Varda upends the stereotypes embodied in the ‘La Belle P.’ song, to project her protagonist’s gaze onto others. By so doing, Varda’s scoring of ‘La Belle P.’ in the café Dôme scene presents a counterpoint to the jazzy ‘Swing Swing Swing’ composed by Legrand that same year for Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962) which strengthened female alienation.[9]

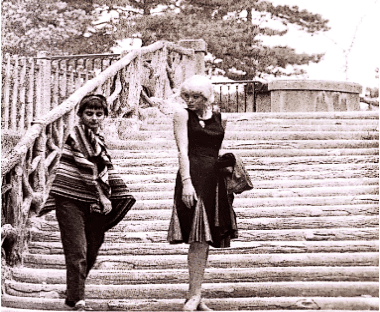

In the final reprise of ‘La Belle P.’ during the third act of the film, Varda directly challenges the male gaze. On the steps of Parc Montsouris, Cléo parodies her song by miming a series of exaggerated femme fatale poses and singing snippets of the lyrics’ references to her ‘precious and capricious body’ and ‘the blue of her audacious eyes.’ Through Cléo’s mocking of her own glamourous pop star image Varda subverts cinematic constructions of the female body as a vehicle of male sexual pleasure (Figs. 8-9). As the musical interlude in the park mixed with the theme of nature continues, the sounds of birds grow progressively louder on the soundtrack interrupting the cabaret-like performance. Symbolising freedom but also echoing other shots in the film, the sound of birds translates the idea that death is literally following Cléo on the streets of Paris. As Cléo looks for her own truth, music and image convey her strength of character and resilience.

Figs. 8 & 9: Re-appropriation of cinematic constructions of the body (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962).

Figs. 8 & 9: Re-appropriation of cinematic constructions of the body (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962).

It is therefore significant that Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), the only male character in Cléo from 5 to 7 that is in any way sympathetic to the protagonist’s existential crisis, is a French soldier reeling from the horrors of war in Algeria, where men like him are sent to die for no purpose. Varda explores the characters’ shared anxiety of death as a vantage point to unravel limiting representations of gender and identity: a woman objectified for her beauty and a man for his bravery. It is the music that has the last word as to their fate. In the film’s fadeout, as Cléo and Antoine turn towards each other (not romantically) but with understanding and compassion, four disparate, dissonant chords emerge on the soundtrack. Evoking and contrasting with the ominous sounds of the shuffling fortune-teller’s cards that accompany the film’s title sequence, the anempathetic music serves both to intensify the pathos of the image and to interrogate myths about ideal femininity. The viewer perceives that Cléo’s transformation is propelled not by the probability of death, but by her awareness of the life already surrounding her. The music cue in the film’s denouement can also be read as a metaphor for Varda’s feminist politics. As Hilary Neroni states, ‘Varda’s questioning stance provides a rich example of the very project of feminism itself’ (2016: 2). What distinguishes her work with music in Cléo (and Le bonheur) is its exploration of the contradictions of the feminine on the filmic screen.

Female Voices Subverting the Male Gaze

While Thérèse et Émilie are far less emboldened than the rich portrait of Cléo, both films present female characters as objectified for their sexual attractiveness to men, and can be read as feminist satires which elevate the voices of women. Although cinematic dialogue shapes the perception of images and gives them meaning that they would not normally have on their own, its role as an essential component of cinema is relatively little explored by theorists. Michel Chion is part of debates affirming the predominance of the human voice in the soundtrack, called ‘vococentrism,’ which serves to ‘hierarchize the perception around it’ (1982: 15). Adopting his concept, I argue that Varda taps into verbal plays often executed through ironic editing—between what the viewer hears the characters say to each other and the unsaid—to raise questions of agency in the face of objectification. In Le bonheur, for example, as the protagonists discuss Viva Maria (1965) starring Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau, Thérèse asks ‘quelle femme préfères-tu?’ (Which woman do you prefer?). François’ response ‘You’ intercuts to photographic images of the film’s female actors. This moment that Varda sets aside for contemplation recalls the taxi scene in Cléo de 5 à 7. Playing diegetically on the radio, a voice-off announces a new shampoo for American women made of whisky, which ‘revitalises the hair.’ As the acousmatic voice says this, Varda cuts to a shot of Cléo’s assistant Angèle (Dominique Davray) patting her hair. The effect of the dialogues and conspicuous, fragmented editing ‘add value’ and yield their hidden subtext. Staged by Varda in a quasi-carnivalesque play on the rules of cinematic illusion, both scenes nod to the way mass media reinforces tropes of ideal female beauty.

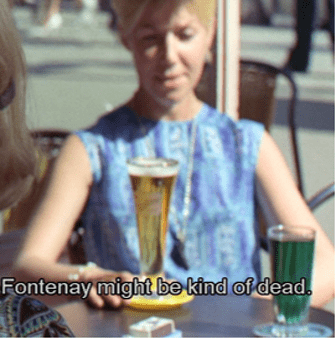

The hyper-feminine visual code that Varda examines closely—and, we may conclude, critically—is the stereotypical ‘pretty blonde.’ The ‘blonde’ as an idealised object and glamorous model of sexual and racial femininity emerges in mid-century Western culture, personified by Marilyn Monroe. The juxtaposition of purity and eroticism embodied in the image of the blonde manifests in each studied film, and in Le bonheur not only in the form of the Thérèse and Émilie characters but also Varda’s intertexts to popular iconography. The context and visual of the ‘pin-up’ to which the film returns repeatedly also serves as an ironic mise-en-abyme of the filmmaker’s visual artist background. Assembled in a collage adorning the masculine milieu of the carpentry shop, Varda playfully lingers on a shot of François standing in front of a poster of the 1960s French pop star Sylvie Vartan who resembles Corinne Marchand and Marie-France Boyer; ‘a sort of thought bubble,’ explains Holst-Knudsen, as ‘this guy has women on his mind all the time’ (2018: 517). Varda enriches this portrait of male entitlement by incorporating references to Vartan’s singing voice playing diegetically on the radio. Her voice serves to interrogate gender differences and spaces in the film. Within these heteronormative binaries, Varda plays on the classic opposition between the virgin (the mother) and the whore (object of desire), as suggested by François’ description to Émilie: ‘Thérèse is like a hardy plant. You’re like a wild animal set free. I love nature.’ While Émilie lives out a version of both narratives described by Dagmar Herzog—first a sexually liberated object of desire, evoked by her dialogue to François ‘I am free, happy, and you are not the first,’ and then a dutiful housewife and surrogate mother—her freedom is limited (2011:107). This is underscored by a darkly ironic line of dialogue in the café scene in which Émilie asks François if there are any cinemas and dance halls in the town, as she heard ‘Fontenay might be kind of dead’ (Figs. 10-11). The flirtatious banter foreshadows Thérèse’s death and is highly subversive. François believes he can simply add her, ‘le bonheur s’additionne’ (happiness works by accretion) and ultimately assimilates the once liberated Émilie to his cookie-cutter vision of conjugal happiness. Juxtaposed with the posters of Vartan and Monroe on the wall of Émilie’s apartment, echoing those of the pin-ups on the cabinet door in the carpentry shop, the dialogues crafted by Varda shape viewer understanding as female voices, faces, and bodies are indistinguishable.

Figs. 10 & 11: Ironic use of dialogue (Le bonheur, 1965).

Figs. 10 & 11: Ironic use of dialogue (Le bonheur, 1965).

Varda foregrounds questioning of the ‘pin-up’ with the explicit repetition of clichés where women are ‘dolls,’ or ‘desserts.’ The most notable example is when François tells his wife, ‘Moi, ce que j’aime, je le prends tous les jours’ (I indulge in my favourite foods daily), which intercuts to a shot of Émilie akin to the satirical juxtapositions crafted with Mozart’s music. The visual repetition and verbal play create a lulling effect before it culminates in Thérèse’s tragic death. As François searches for Thérèse in the park, he repeatedly describes her in stereotypical terms as ‘une jeune femme blonde’ (a young blonde woman). One of the shots dwells on the reaction of a middle-aged blonde woman. When François moves out of frame, she turns to the camera and shrugs her shoulders. Only within the piercing cry of young Gisou’s ‘Maman’ is the true austere reality of the situation presented. What should be a shocking moment is instead immediately compartmentalised and the power of the patriarchy to objectify women is underscored by François’ re-established nuclear family.

In both Le bonheur and Cléo de 5 à 7, Varda is clearly tapping into and interrogating how societal obsessions with images turn people into spectacles to consume. Varda employs sound and codes of Hollywood cinema in a subversive way to illuminate the protagonist’s self-discovery, with the overarching presence of death in both films strongly alluding to the Hitchcock blonde in danger. ‘Tant que je suis belle, je suis vivante et dix fois plus que les autres’ (As long as I’m beautiful, I’m ten times more alive than other people), Cléo declares when she speaks to her reflection at the bottom of the tarot reader’s stairs. The overarching presence of death around Cléo, punctuated with the sound of birds following her, underline clichés around female vulnerability. Together with words, vocal register and tone, explains Chion, draw attention to the image, giving it a presence and lending meaning to the story, in the same manner as a shot or a camera movement in cinema do (1982: 15-16). The whispery affected voice that actor Corinne Marchand adopts in this scene, adds another layer of understanding to the protagonist’s broken self as she tries (and fails) to re-assume the image. In addition to the power of the human voice to orient perception and create empathetic effects, Varda experiments with the sound of Cléo’s high heeled shoes, another gesture to modes and constructions of femininity. The viewer adopts Cléo’s point of view when she emerges from the Dôme café, as all sounds disappear except the sharp clip-clop on the sidewalk, while the camera encounters the threatening gazes of men staring at her. Therefore, Varda transposes the feeling of heightened awareness and entrapment that marks the female body as an object of desire. Playing on audio-vision, the juxtaposition of sound and image, she encourages the spectator to see the incongruities of a ‘beautiful, tall, blond woman who is in danger, who is attacked by fear and by illness’ (Varda 2011: 190).[10] By performing the dominant social order’s idea of the perfect woman and being defined by something that by its very nature is fleeting and disconnected, Cléo’s identity is compromised. Added to that contradiction, between ideological messages and lived experience, the soundtrack is a metaphor of the protagonist ‘walk[ing] towards something’ (Varda 2011: 190): this discovery of herself which, as Varda states, is ‘always the first step in claiming one’s feminism’ (2014: 73).

The discussion with the female taxi driver highlights Cléo’s increasing distance from her own position as an objectified woman and is the most overtly feminist moment in the film (Fig. 12). The character drives a car in the film: a traditional masculine task and profession in the 1960s. The cab driver’s dialogue to Cléo and Angèle, ‘C’est un dur métier pour une femme, et même un peu dangereux aussi, mais moi j’aime ça’ (tough job for a woman, dangerous too, but I like it), corresponds to what Chion terms ‘theatrical speech’ (2003: 65-66), which guides the action and transforms the meaning of the scene being played. The exchange and the protagonist’s response, ‘Et la nuit? Vous n’avez pas peur la nuit?’ (And at night; aren’t you afraid at night?) emphasise fear and vulnerability: the aspects of being a woman to which Cléo is attuned. As the taxi driver recounts a story about being attacked, replying ‘Je ne suis pas peureuse’ (I’m not the fearful type), the sequence seems to echo cultural preoccupations of Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) (1960) filled with references to American gangster pictures. The subversive element here is that the ‘tough guy’ is a woman. Although the film does not condemn either approach to femininity, the cutting, interpretation of actors, and particularly Angèle’s retort that the taxi driver is brave present the latter as a kind of hero on the streets of Paris and contrast with the ideal femininity represented by Cléo.

Fig. 12: Opposing responses to the feminine ideal (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962).

Fig. 12: Opposing responses to the feminine ideal (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962).

Speaking to Pierre Uytterhoeven in 1962, upon Cléo de 5 à 7’s release, Varda contrasts her filmmaking with that of Demy’s which ‘presents a certain reality—not presented as a problem to be solved. … I, on the other hand, make a cinema full of obstacles, of contradictions’ (2014: 11). In later films, such as L’une chante, l’autre pas (1977) and Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), Varda engages in a more frontal critique of gender norms and heteronormative structures using music and sound in counterpoint and conventions of the musical as an act of defiance. Taking as her point of departure and denouement, Mozart in Le bonheur and her collaboration with Michel Legrand in Cléo, Varda works with cinematic anempathetic and empathetic sound effects to comment on both the consequences and mechanics of a male-dominated social structure which views women as disposable. Upending expectations of certain music such as the problematic ‘La Belle P.,’ a traditional French waltz, and through visual intertext to Hollywood cinematic references, nods to her New Wave male counterparts, and media-reinforced gender norms actualised in the dialogues, Varda deconstructs social constructs of the ‘blonde.’ The soundtracks provoke the viewer to reflect on traditional gender roles, embodied in the ‘pin-up’ and stereotypical gender tropes. The rich juxtapositions between music, dialogues, and images, expose the logic of male entitlement to its most absurd extreme so that the films hold up a mirror to our most complicated realities.

Notes:

[1] Translations are the author’s own unless otherwise specified.

[2] Varda’s interview was published in English.

[3] Also see Crittenden (2014: 29-39).

[4] See also Alison Smith (1998) and Kelley Conway (2015). Following a brief analysis of Le bonheur’s critique of the male-dominated social order, Smith dismisses the film, admitting that despite its virtuosity and complexity, she finds it chilly and hard to like (45).

[5] It has also been labelled as a reactionary film. See Johnston ([1973] 2006: 31-40).

[6] See ‘Agnès parle du Bonheur’ (Agnès Talks About Happiness), which is featured in the Criterion Collection.

[7] According to the Oxford Dictionary of Music, musical inversion refers to ‘the turning upside down of a chord, interval, counterpoint, theme, tone row, or pedal point’ (Kennedy 2012: 230). In each of these cases, inversion has a distinct meaning.

[8] Varda wrote the lyrics of the song Sans toi. In this pivotal scene, Legrand plays the role of Bob: Cléo’s songwriter and musical accompanist.

[9] The upbeat music in Godard’s film punctuates its female protagonist’s struggles for agency. As Nana (Anna Karina) dances to ‘Swing Swing Swing’ on the jukebox, the contradiction of the ‘happy dance’ accentuates cinematographic illusions and the character’s alienation. Godard and Anna Karina made cameos in Cléo de 5 à 7.

[10] Varda’s interview was published in English.

REFERENCES

Barnet, Marie-Claire & Shirley Jordan (2011), ‘Interviews with Agnès Varda & Valérie Mréjen’, L’Esprit Créateur, Vol. 51, No. 1, pp. 184-200.

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, New York: Columbia University Press.

Chion, Michel (2021 [1990]), L’Audio-vision: son et image au cinéma, Paris: Armand Colin.

Chion, Michel & Claudia Gorbman (2021 [2019]), Musique au cinéma/ Music in Cinema, Paris: Fayard.

Chion, Michel (2003), Un art sonore, le cinéma. Histoire, esthétique, politique, Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma.

Chion, Michel (1985), Le son au cinéma, Paris: L’Étoile.

Chion, Michel (1982), La voix au cinéma, Paris: Éditions de l’Etoile.

Conway, Kelley (2015), Agnès Varda, Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Crittenden, Roger (2014), ‘The Sound of Agnès Varda’, The New Soundtrack, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 29-39.

DeRoo, Rebecca J. (2008), ‘Unhappily Ever After: Visual Irony and Feminist Strategy in Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur’, Studies in French Cinema, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 189-209.

Einstein, Alfred, Arthur Mendel & Nathan Broder (1962), Mozart, His Character, His Work, New York: Oxford University Press.

Felleman, Susan (2021), ‘Show the Clichés: The Appearance of Happiness in Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur’, Acta Univ. Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, No. 19, pp. 17-34.

Flitterman-Lewis, Sandy (1996 [1990]), To Desire Differently: Feminism and the French Cinema, New York: Columbia University Press.

Gorbman, Claudia (2008), ‘Varda’s Music’, Music and the Moving Image, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 27-34.

Herzog, Dagmar (2011), Sexuality in Europe: A Twentieth-Century History, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Holst-Knudsen, Heidi (2018), ‘Subversive Imitation: Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur’, Women’s Studies, Vol. 47, No. 5, pp. 504-526.

Johnston, Claire (2006 [1973]), ‘Women’s Cinema as Counter-Cinema’, in Sue Thornham (ed.), Feminist Film Theory, A Reader, New York: New York University Press, pp. 31-40.

Keefe, Simon P. (2017), Mozart in Vienna: The Final Decade, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kehr, Dave (2008), ‘4 by Agnès Varda’, New York Times, Entertainment Section, 22 January, p. 5.

Kennedy, Joyce, Michael Kennedy & Tim Rutherford-Johnson (2012), The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Neroni, Hilary (2016), Feminist Film Theory and ‘Cléo from 5 to 7’, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Quart, Barbara Koenig (1986), ‘Agnès Varda: A Conversation’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 126-138, http://womenfilmeditors.princeton.edu/assets/pdfs/VARDA_Conversation_Barbara_Quart.pdf (last accessed 14 July 2023).

Schroeder, David (2012), Hitchcock’s Ear: Music and the Director’s Art, New York: Continuum.

Smith, Alison (1998), Agnès Varda, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Taubin, Amy (2008), ‘Le Bonheur: Splendor in the Grass’, Criterion Collection, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/500-le-bonheur-splendor-in-the-grass (last accessed 14 July 2023).

Tigoulet, Marie-Claude (1991), ‘Voyage En Pays Féminin’, in Michel Estève and Bernard Bastide (eds), Agnès Varda, [Série: Études cinématographiques], Paris: Lettres modernes: Minard, pp. 57-70.

Varda Agnès & Bernard Bastide (1994), Varda par Agnès, Paris: Editions Cahiers du Cinéma.

Varda, Agnès (2008 [1998]), ‘Agnès parle du Bonheur’ (Agnès Talks About Happiness), in ‘4 by Agnès Varda’, Criterion Collection.

Varda, Agnès (2014), Agnès Varda: Interviews, in Jefferson T. Kline (ed.), Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Films

À bout de souffle (Breathless) (1960), dir. Jean-Luc Godard.

Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962), dir. Agnès Varda.

L’une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t) (1977), dir. Agnès Varda.

Le bonheur (Happiness) (1965), dir. Agnès Varda.

Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), dir. Agnès Varda.

Singin’ in the Rain (1952), dirs. Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly.

Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live) (1962), dir. Jean-Luc Godard.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey