Fragmentation & Reconstruction: Varda’s Radical Deconstructions of the Self

by: Kierran Horner , November 7, 2023

by: Kierran Horner , November 7, 2023

Introduction: The Multiple Self

In response to the request for proposals for the Reframing Varda conference, which were to be based on a single still or photographic image, I took the opportunity to analyse a shot from Varda’s first film, La Pointe Courte (1955) in which the two lovers’ faces are split yet enclosed by the frame (Fig. 1). This still image spoke to me of the construction of female identities in Varda’s work. In the films and art pieces analysed here, bodies are deconstructed, morphed, stretched, multiplied. The complex identities they represent become fluid and fluctuating. In this essay, I propose that Varda portrays female subjectivities in such terms, embracing the potential to be both the subject and the other within intersubjective relations: the self as a polysemous I.

Fig. 1: La Pointe Courte (1955): the lovers’ faces are split yet enclosed by the frame.

Fig. 1: La Pointe Courte (1955): the lovers’ faces are split yet enclosed by the frame.

There are several instances of the Cubist-inspired images of the overlapping lovers in La Pointe Courte. The characters are referred to simply as She (Elle) and He (Lui) [1]. In the first of them, She gazes into the camera as He stares off-frame. She tells him that She thinks that they only remain together out of habit. In the second, He asserts that He still loves her and is content in their relationship, reversing the gaze—the positionality and authority—of the two characters (Fig. 2). These shots, mere instants apart in the narrative, speak to a subject-other relation structured by gender equality, in opposition to the orthodox hierarchy of patriarchy. As Varda explained fifty years later in Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès, 2008), her compositions echo the abstract portraits of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Yet where such canvases depict single subjects observed from multiple perspectives, the images in La Pointe Courte form a single face from two entities: dual selves in a couple. [2] These compositions exhibit the implicit impact on the subject of an external other and the otherness inherent in every self. Speaking to such a multiplicity, feminist theorist Luce Irigaray writes that ‘[w]oman always remains several, but she is kept from dispersion because the other is always within her’ (1985: 31). For Irigaray, the elaborate essence, the polysemous I of the female figure, is sustained by the acceptance of the otherness within us.

Fig. 2: The position of the two lovers is reversed.

Fig. 2: The position of the two lovers is reversed.

These shots of the overlapping lovers in La Pointe Courte reflect a complexity which is echoed later in the film as the couple lie in bed together. Varda’s camera is positioned at the level of the bed filming them staring at the ceiling, discussing their partnership. She argues that they have lost the passion in their relationship. As He turns toward the camera to look at her, their visages overlap again, though now in a vertical version. They agree they know one another too well not to continue, but She asserts that their future relationship might be different: they may not live together, they might enjoy more freedom from one another outside conventional hetero-normative co-dependency. As Annette Raynaud wrote in a contemporaneous review of the film, She ‘is a female subject, capable of realising her full potential without ceding her ground to the man’ (1955: 267). The couple end the narrative together, acknowledging their resonance within one another, but their relationship is now defined by Her as fluid.

In the discussion that follows, I investigate further images in Varda’s films and artworks in which the fragmentation and reconstruction of faces and bodies interrogate the feminist implications of these corporal portraits. According to Julia Prest and Hannah Thompson,

[the] transformation of the corps morcelé into the corps rassemblé marks the point where the corporeal body coincides with the represented body. It is the moment where skin, bones and flesh become mediated through the artistic imagination (2000: 9).

I will argue that Varda exploits this conjunction of the material and the aesthetic to challenge traditional depictions of female bodies, deconstructing them into their formative elements in order to reassemble them as complex selves that are constantly in flux.

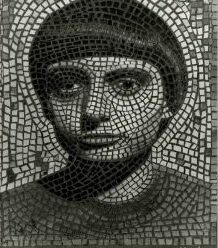

In two examples of photographic self-portraiture, Varda splinters her own face into multiple components: in Autoportrait (Mosaic Self-Portrait, 1949) and again, sixty years later, in Autoportrait morcelé (Fragmented Self-portrait, 2009). These shattered autoportraits speak to the complexity of their subject. According to Dominique Bluher, Varda’s intention is ‘to fix [the subject’s] identity and, at the very same time, to express its dynamic, changeable, and temporal openness to otherness’ (2019: 49). This sophisticated female self is evident in an early shot from Documenteur (1981) (Fig. 3). She films Sabine Mamou as Emilie (an avatar of Varda herself, not least as Emilie’s son Martin is played by her own child, Mathieu Demy), as she gazes through a chain link fence at Martin playing with other children. The diamond links of the fence splinter Emilie’s form, as in the two self-portraits, as Emilie contemplates her life and her son’s future after the breakdown of her relationship with the boy’s father. Once again, the female self is presented in a complex state of becoming, projecting forward from the present to the future.

Fig. 3: Splintered faces: Vardian Autoportrait and Autoportrait morcelé (© Succession Agnès Varda) [3]; Sabine Mamou as Emilie in Documenteur.

Fig. 3: Splintered faces: Vardian Autoportrait and Autoportrait morcelé (© Succession Agnès Varda) [3]; Sabine Mamou as Emilie in Documenteur.

Varda’s work employs such fractured corporeal images as metaphors for both the constitution of an ‘I’ that is fluctuating, never completed, and the discombobulation of a character at a particular point in the narrative. Kaja Silverman writes of the subject ‘rediscovering her-self’ in cinema as ‘splittings or divisions [which] produce both subject and object’ (1999: 97). Varda’s female characters are manifold selves, outwardly displaying the experiences and positions from which they are constructed within phallocentric inventions of intersubjective hierarchies, particularly of the masculine subject objectifying the feminine through the gaze. Thus, Varda shows the witnesses in Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), who act as mirrors for the perspectival multivalence of the vagabond Mona; the eponymous widows (including a silent portrait of Varda) in the installation piece Les veuves de Noirmoutier (The Widows of Noirmoutier) (2005), with its fourteen short video profiles; and the collected interviewees of Réponse de femmes: notre corps, notre sexe (Women Reply) (1975) who discuss their experiences of life in a society that defines them by their biological difference. It is especially prevalent in Varda’s exploration of complex multiplicity within presentations of the mirror image.

Mirroring the Gaze, Reflecting the Patriarchy

According to Teresa de Lauretis, the ‘specular image’ of the cinematic female form is ‘ob-scene, woman is constituted as the ground of representation, the looking-glass held up to man’ (1984: 15). Varda critiques the male possession of the image and the patriarchal objectification of the looked-upon throughout her work. For instance, in a trompe–l’œil sequence in Jane B. par Agnès V. (Jane B. by Agnès V.) (1988), the titular Jane Birkin is filmed looking into an ornate mirror, yet it is Varda who is reflected in the glass. The director undermines the spectator’s phallocentric expectations, denying a penetrative gaze at her ‘star,’ thwarting the speculative gaze, and refusing what the audience might expect, perhaps even desire to see. Irigaray argues that, as the male gaze seeks to speculate the inner secrets of the female figure, an exploration of the workings of the mirror itself helps contest this coveting and sexualising look (1994: 146). The result is a complex figure which repeats as a mise-en-abyme throughout Varda’s work.

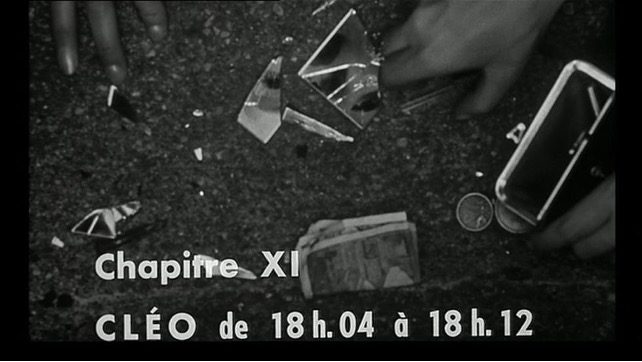

In Autoportrait, Varda photographs herself in a mirror and cuts the print into tiny fragments, before reconstructing it as a mosaic. The mirror is also at the centre of Autoportrait morcelé in which her face is reflected in shards of shattered mirror. She had previously used this aesthetic device in Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962). After Cléo watches the short film-within-a-film, Les fiancés du pont MacDonald (The Lovers of the Bridge MacDonald) she descends a stairwell with her friend Dorothée. On the last step, Dorothée drops her handbag, its contents spilling over the floor and her compact mirror shattering on the cobblestones of the alleyway. As Cléo bends to help her friend pick up her make-up and accessories, her splintered face reflects in the shattered glass (Fig. 4). This shocking moment intimates her inner anguish, the oscillation between self and other before her final acceptance of her-self as a polysemous composition of each performance. These splintered visages, portraits brisés, attest an amorphous subject that learns to deny the objectification of the penetrating gaze. They speak to what Diana Fuss has called the ‘postmodern identity’ which is ‘atomic,’ ‘fractured,’ and in which difference is ‘a product of the friction between easily identifiable and unitary components of identity (sexual, racial, economic, national…) competing for dominance within the subject’ (1990: 103).

Fig. 4: Cléo de 5 à 7: Cléo’s splintered face reflected in the shards of the shattered glass.

Fig. 4: Cléo de 5 à 7: Cléo’s splintered face reflected in the shards of the shattered glass.

Cléo’s journey towards this position begins with her mirror-reflection at the beginning of the film, where her sense of self has been fractured by the tarot-reading in which the fortune-teller reveals the presence of the ‘Death’ card. As Cléo descends the stairs from the fortune-teller’s apartment, Varda uses the staccato editing of the jump-cut to depict what Annabel Brady-Brown calls the singer’s ‘shattered sense of self’ (2017: 12). When she reaches the ground floor of the building, Cléo looks into a mirror and is both fractured and multiplied in a second mirror hanging opposite the first (Fig. 5). Her encounter with death instigates an odyssey towards an acceptance of this splintered multiplicity and its performance in the fleeting romance of her encounter with the soldier Antoine.

As well as representing Cléo as a self who comes gradually to resist definition by others, Varda’s film also plots its protagonist’s recognition of their importance. As Varda herself puts it, she ‘starts to listen to other people’ (Reardon 2018). Judith Butler writes of the essentialness of the other in subject-identities:

If the ‘I’ is separated from the ‘you’ or indeed the ‘they’, that is, from those without whom the ‘I’ has been unthinkable, then there is doubtless a rather severe disorientation that follows. Who is this ‘I’ in the aftermath of such a break with those constituting relations, and what, if anything, can it still become? (2015: 9)

The ‘I’ is nothing without the presence within it of ‘you’ or ‘they.’ Cléo experiences this need when she encounters the certitude of mortality.

In Jane B. par Agnès V., through a further reflection in a looking-glass, Varda denies the objectification of the male gaze by presenting Birkin as a nebulous female ‘I’ always becoming a more complicated version of itself. She films Birkin looking into a warped mirror, where her face is distorted, drawn out of form (Fig. 6). Later, she is filmed dancing in ten mirrors with seams running horizontally across each glass, splitting her at the waist. These sequences are deliberately esoteric, resisting capture and possession by the spectator-subject. Birkin is acutely aware of the gaze upon her, working with Varda to collectively compose her own sophisticated image.

Fig. 6: Jane B. par Agnès V: Birkin’s face distorted and drawn out of form in the mirror.

Fig. 6: Jane B. par Agnès V: Birkin’s face distorted and drawn out of form in the mirror.

Resisting the Sexualising Gaze

A sequence in Documenteur similarly plays on the device of a mirror reflection split by a join in the glass. Throughout the film, Emilie is doubled in windows and mirrors, alluding to the protagonist’s inner turmoil, as in Cléo. These shots build to a climax in the scene after Martin asks Emilie how she and his father met. Evidently upset, she tells him to stop repeating the same questions. A montage of a photograph of Emilie, Martin and his father, and murals of other families, is then interjected into the scene, suggesting that Emilie’s thoughts have nevertheless been stimulated by her son’s enquiries. This scene then cuts to a sheet of paper in a typewriter as Emilie writes. A close-up on the page reveals the phrase ‘Séparation de corps’ (Separation of bodies) repeated several times. [4] Above Emilie’s lines are typed, ‘Lettre Morte’ (Dead Letter) and ‘Lettre Mots’ (Letter Words) a couple of times each, then at the end of the page both ‘Mots Séparés’ (Separate Words) and ‘Phrase Brisée’ (Broken Sentence) are typed once. These esoteric slogans, as with the montage of portraits, reveal Emilie’s inner conflict, the breakup of her relationship, the dissociation in the script she is writing, and the distance of her body from an/other’s, her frustrated desire(s). At the foot of the page are written the words, ‘Brise de mer’ (Sea Breeze) (with its further play on ‘Brisée’), ‘Amer’ (Bitter) and ‘Amers’ (Bitters), riffing on the polyphones ‘à mer’(at [the] sea) and ‘amour’ (love), indicating the bi-lingual bitterness and fragmentation Emilie feels at her lost—and lacking—love.

As Emilie continues to type, there are inter-shots of a painting of a skeletal hand and the mural-family that interceded in her earlier conversation with Martin. A cut reveals her speaking on the phone as she wanders the same room looking out through an open door at the beach (‘à mer’) where her body is reflected several times in the room’s windows depicting its fracturing, as she writes in her script, but also multiplying it. She re-enters the room where her reflection is once more caught in a mirror, then—via an edit—walks into the bedroom. There she makes an inventory in voiceover of the possessions she and Martin’s father owned together, before she undresses slowly and reclines on the bed. Her naked form is reflected in large mirrors on the front of the doors of a wardrobe running parallel to the bed before the sequence is intercut with shots of Martin playing and neighbours working, then returning to the prone Emilie. As she looks into the mirrors, there is a cut to a still-life composition of a vanity-mirror, an empty vase, a photo of two lovers embracing, and a statue of a rose with its pink petals unfurling like frills or lips, indicating Emilie’s frustrated desires and the potential that they might be fulfilled. The shot returns to Emilie on the bed where details from paintings of a spaceman and a cowboy—signifiers of a certain tradition of super-masculinity—intercede. Emilie poses/ reposes nude—an odalisque, typically an eroticised portrait of a naked woman reclining on a divan—but the portrait is filmed in duplicate as it is also reflected in the mirror. As the camera passes over her naked body in reflection, she stares back into the lens, meeting the spectator’s gaze. Her face is split by a join in the mirror. It speaks to the fractured state of Emelie’s consciousness as she contemplates her position without the boy’s father and her unfulfilled sexual desires. But her steely look, returning the gaze, and her decision to undress and to contemplate her own image empowers her (Fig. 7). Reappropriating the artistic form of the odalisque, she achieves dominion over her body. Shortly after this sequence the camera tracks into a shop-window full of dismembered mannequins, shattered and rearranged, and an edit moves to a pan along a model’s detached leg. A match-cut then presents the human, entwined limbs of Emilie and Tom, her new lover, the camera tracking along their interwoven bodies. Emilie retains her agency even as the camera emblazons their bodies in a slow tracking-shot. She has reclaimed autonomy, relinquishing her-self to desire on her own terms.

Fig. 7: Documenteur: Emilie returns the gaze.

Fig. 7: Documenteur: Emilie returns the gaze.

Varda explores a similar artistic trope in Jane B. Here too Birkin’s nude female figure lies prone on a divan. The camera tracks along the contours of her body, displaying it part by part—toes, heel, calf, thigh—until it finally rests on her eye which, like Emilie’s, stares back into the lens. Emma Wilson writes of Varda’s treatment of this recumbent figure:

I see the reclining nude with her listlessness as a figure for thinking about opacity, vulnerability, and estrangement. This touches on questions about knowing and unknowing, about telling one’s own story or the story of another, that have preoccupied some strands of feminist philosophy and ethics. (2019: 6)

For Wilson, the reclining nude addresses an obscurity and a simultaneous susceptibility, a state in which one holds one’s own narrative, including one’s vulnerability, or trusts the telling of it to the vision of another. As Birkin reiterates in Jane B., her request to Varda to work on the film together was inspired by her impending fortieth birthday which raised for her questions about her-self, how she was portrayed in popular images after her youthful notoriety which often—witness the actresses’ apparent comfort with posing nude and the media’s obsession with sexualising her (youthful) female form—centred on Birkin’s naked body. The two women are in dialogue with these depictions throughout the film. In the slow tracking along Emilie’s and Birkin’s exposed bodies, Varda problematises patriarchal parameters pertaining to terms such as ‘feminine’ and ‘femininity.’ Her repertoire of techniques for filming the reclining female form—its representation through mirror-reflections, the presentation of a look that opposes the lens and the spectator’s objectifying gaze—shatters the figure into the multiple parts that constitute a subject, before reassembling them into a complex whole.

As Varda explained to Mireille Amiel in a 1975 interview, ‘For me, to be a woman is first of all to have the body of a woman. A body which isn’t cut up into a bunch of more or less exciting pieces, a body which isn’t limited to the so-called erogenous zones (as classified by men), a body of refined zones’ (2014: 74). These comments resound through her short TV documentary, Réponse de femmes: Notre corps, notre sexe (Women Reply), released the same year. The women in the film gather in a brightly lit studio to talk to camera about several topics affecting their daily lives, including motherhood, the non-consensual linkage of women’s sexuality to the exposed and fragmented female body, and the monetisation of images depicting nudity. After the opening inter-titles, the actress Caroline Baudry stands naked in medium shot stating that, ‘To be a woman is to live in a woman’s body. It’s me, my entire body.’ Over a close-up of her face she insists, ‘I am more than the hot points of men’s desire. I am not just sex and breasts,’ as the camera hovers in closeup above her individual breasts and pubic hair. ‘I am a woman’s body,’ Baudry asserts finally, over a medium shot taking in her whole, uncovered body (Fig. 8). Her words and Varda’s images parlay the director’s comments to Amiel: women are not simply ‘a bunch of exciting pieces.’ Baudry’s opening declaration cuts to a sequence of pictures, paintings and photographs ending with a close-up of a woman’s face and head—a collar about her neck indicating that she is likely clothed—asserting that, ‘Being a woman is also to have a woman’s head.’ The traditional locus of consciousness is emphasised, instead of erogenous zones deemed erotic within hetero-patriarchal convention. Varda’s approach anticipated Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990), fifteen years later, where Butler writes:

Not only is the gathering of attributes under the category of sex suspect, but so is the very discrimination of the “features” themselves. That penis, vagina, breasts, and so forth, are named sexual parts is both a restriction of the erogenous body to those parts and a fragmentation of the body as a whole. (1999: 46)

I do not suggest that Varda deconstructs binary definitions of sex, as Butler does. But I do posit that she explicitly satirises the eroticising gaze that fragments the female body into specific sexualised parts. Her compositions of the female form speak to a sovereign self that is above all, resistant to a reductionist gaze that compartmentalises women as a collection of eroticised body parts. Later in Réponse de femmes, the women and Varda (present in the text in voiceover and script) define themselves as beyond sexist categories. Baudry says, ‘I can no longer stand to be loved by misogynists,’ then Varda cuts to an arrangement of gathered men of all ages looking back into the lens of the camera as she continues, ‘How do we be women outside of men’s opinion?’ The gathered women offer alternative depictions of womanhood. The first of a group of three asks, ‘What is a woman’s body,’ the second follows with, ‘if we must all account,’ before the third finishes the question: ‘for our weights and measures?’ [5] In a patriarchal system, women’s bodies are catalogued by the sexualising reduction of the bust-waist-hips trinity, which must align to fit Western hetero-masculine definitions of ‘attractiveness.’ A later sequence presents a group of four, including Baudry, asking collectively, ‘How do we live our sex?’ They then answer their own question: ‘We do not appear naked in this film gratuitously,’ ‘Nor to be ogled,’ and ‘Pleasure not perversion.’ The nudity displayed in the film is not for male sexual gratification but a reappropriation of such images of women’s bodies and their presentation as complete entities in a multitude of equal forms, measurements, weights, ages. [6] Finally, the fourth of these women looks directly to camera and says, ‘You live in contradiction when you live in a woman’s body.’ This cuts to a single woman describing this absurdity: ‘We’re told, “Hide yourself, cover your sex.” And then we’re told, “Show yourself, your body sells!”’ The women’s comments critique the classic Madonna and whore paradox. Baudry restates this enigma when she says that she is told to show her legs: ‘the customers like it.’ Over shots of magazine adverts of nude women and various goods, including office furniture, the actress explains that she doesn’t condone the use of her body to sell products: ‘I don’t like my body being exploited to boost sales.’

Fig. 8: Réponse de femmes: ‘I am not just sex and breasts.’

Fig. 8: Réponse de femmes: ‘I am not just sex and breasts.’

In addition to the odalisque discussed above, Varda employed the compositional framing of another traditional art format in Lions Love (… and Lies) (1969). The shot of Viva composed as three body parts within picture-frames recalls the triptych, as her right leg, her breasts, and face are enclosed separately but, absurdly, with the picture of her head beneath her breasts (Fig. 9). In an obvious pastiche of this abbreviation of the female form to eroticised parts, the image might be described more as a dissection than a multiplication. Varda offers erogenous fragments of Viva’s body, yet uncannily reconstructs the dissevered pieces in a satirical grotesque: a being that could never survive except perhaps in the fantastical world of hetero-normative desire, with its one leg, two breasts, each dismembered, and a decapitated head hovering between them. Varda parodically offers the penetrative, masculine gaze a view on the naked female form but as a dissociated, cryptic figure and, as with Réponse de femmes (‘Being a woman is also to have a woman’s head’), places the head, and therefore the mind, at the centre of the arrangement. This notion reverberates through the film as Varda gives Viva wider agency as she presents a political perspective in which nudity is a challenge to bourgeois social norms. Throughout her films and artworks, women’s bodies are, for Varda, a site of political struggle. The director actively combats the diminution of female subjects to their (sexualised) bodies, even while giving value to the nude female form as a figure of sexual difference, highlighting difference through the pregnant belly in L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958) for instance, or the naked figures given voice in Réponse de femmes. Varda does so to create complete and complex images of women capable of mimicking the phallocentric gaze, mocking its attempts to parse women’s bodies into zones of the erotic at the expense of their inner lives.

Fig. 9: Lions Love (… and Lies): reconstructed body parts as a satirical grotesque.

Fig. 9: Lions Love (… and Lies): reconstructed body parts as a satirical grotesque.

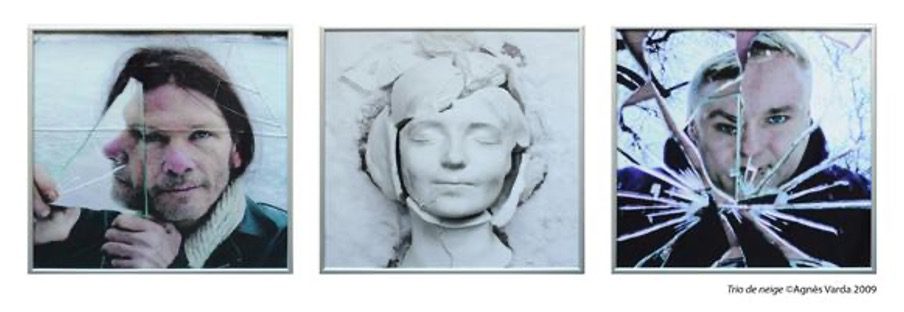

In Jane B. Varda discusses an example of this failure to acknowledge a woman’s consciousness. The director describes hearing as a child the story of L’Inconnue de la Seine (The Unknown Woman of the Seine)—who, in the 1880s, is believed to have completed suicide by drowning—and the death-mask made of her face because it represented an apogee of serenity and (therefore) feminine beauty. As Varda recounts: ‘No one knew anything about her. So everyone could fantasise about her. She was an extraordinary nobody. An amazing unknown.’ This anonymous woman’s legacy is decided by others who have fragmented her, diminished her-self, her subjectivity defined by others: a cast of one body part that represents an ideal of femininity. As the director comments in the film: ‘A frontal view of a motionless face. That’s all that remains of someone. A motionless face. Like an ID photo. Silent or speaking but facing us.’ The unknown woman has no voice of her own, her identity is beyond her own influence. Rosalyn Diprose writes that the notion of the ‘broken body,’ has traditionally been associated ‘with the bodies and sexuality of women’ (1994: 115). L’Inconnue de la Seine is broken and her sex and serene beauty set forever by a misogynist convention. In a later bid to posthumously apply to the unknown woman a complexity and ambiguity by which she might transcend possession by a gaze that silences her perpetually, Varda positions a shattered copy of the death-mask in her Portraits brisés series, between two other fragmented faces in a further triptych, Trio de neige (2010) (Fig. 10). Varda’s description of the death-mask and its later photographic representation speak to the rejection of the muting of the female voice. In her later digital films, she engages further with this excommunication of women, especially older women.

Fig. 10: ‘L’Inconnue de la Seine’ in Trio de neige (© Succession Agnès Varda). [7]

Fig. 10: ‘L’Inconnue de la Seine’ in Trio de neige (© Succession Agnès Varda). [7]

Varda’s Body of/at Work

Mireille Rosello writes of the celebrated, even notorious shots of Varda’s own body, principally her hands, in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000): ‘Body parts are isolated and scrutinised but the result is the exact opposite of the predatory fragmentation characteristic of a fetishising masculinist gaze’ (2000: 35). As we have seen, Varda denies, inverts, and parodies the speculative gaze at female forms. Rosello argues that she does so even whilst fragmenting women’s bodies into particular parts. In Les glaneurs, the artist films the left side of her face in close-up, particularly the eye which looks into the camera lens. She shows herself combing her hair in a mirror, parting it like opening the pages of an old diary to reveal layers of the past within. A minute earlier, Varda describes the digital cameras she uses over a pixellated portrait of her face which morphs with another shot of a mirror (Fig. 11). Here the images leave traces in the previous frame, images melding together like slow-exposure photography, a morph that creates an effect like a cracked mirror, the face once more appearing in shards, fragmented. According to Yvonne Spielmann, the ‘morph’ is a ‘crucial technique of simulation since parts of the image may be transformed in both ways, back and forth, so that two different moments in time hit each other in a single image unit, creating a paradoxical image position’ (1999: 144).

The morphed image creates an incongruous shot of past and present colliding and perhaps combining, progressing into a future, as each complex self does: imminent, becoming. Significantly, this sequence ends with the camera panning through the living room of Varda’s house on Rue Daguerre, to locate the director reclined on a sofa, but instead of the slow pan along her body as with Jane Birkin and Emilie in earlier examples, the director looks into the camera and holds up a hand to halt filming. Varda filmed her own body throughout her films—or allowed others to do so—especially in her autoportraits. In these later films, Varda fragments her own body with a characteristic glee, but also with an eye on the corporeal changes that mark the process of ageing. Maryse Fauvel (2005: 221) argues that in Les glaneurs the director ‘represents herself through fragments: her hands, her hair, herself disguised as a gleaner…she contemplates her left hand as an estranged part of her body.’ But where Fauvel argues that Varda films her hand as a separate entity, I have suggested elsewhere (2017, 2022) that Varda’s hand is a synecdoche of the director’s body on screen, representing a whole, signifying the inquisitive, probing intelligence of Varda and the projection of her-self towards the external world and its self-constitutive others. She focuses on her hand and other parts of her body as they signify the approach of age, the gradual, inherent degeneration of a younger carnal self.

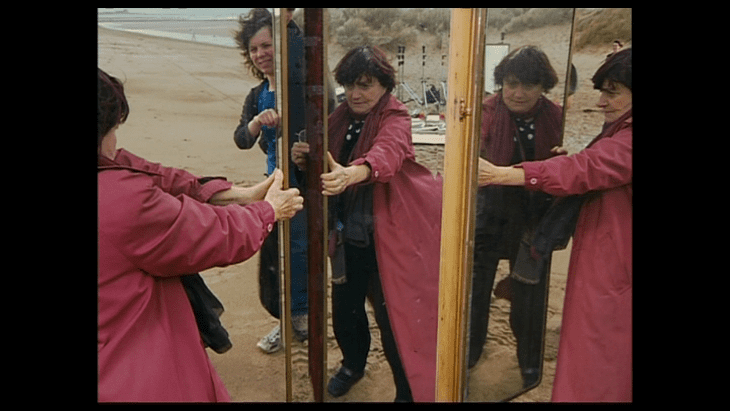

This was a feminist theme in Réponse de femmes, twenty-five years earlier, when a pair of women, one younger, one older, stand together and gaze back into the camera as the first concludes, ‘Men don’t give us the right to grow old.’ In contravention of such a prohibition, in Les glaneurs, its sequel Les glaneurs…deux ans après (The Gleaners…Two Years Later) (2002), Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008) and Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017), the camera fixes fragments of Varda’s body. These images are themselves sometimes splintered further, as if the director were focusing microscopically on the cellular decomposition of her ailing body. In Les plages, for instance, she reassembles her ageing self from the fragments of her past, piecing together the moments in time that constitute her multiple selves. Here, she introduces elements of her own past and presents them, much as she had for Birkin twenty years prior, progressing into a future, along with other aspects of her-self. At the outset of the film, she arranges a collection of mirrors on the beach, in which the director is reflected in mise-en-abyme, her image propagated into perennial becoming, reaching towards an imminent self (Fig. 12). The movement of the wind on these mirrors warp this portrait just as the in-camera morph did in Les glaneurs. These multiplied images resonate beyond the present into the instant of an impending future.

Fig. 11: Les glaneurs et le glaneuse: Varda’s face morphs into a shot of a mirror

Fig. 11: Les glaneurs et le glaneuse: Varda’s face morphs into a shot of a mirror

Fig. 12: Les plages d’Agnès: Varda reflected in a mise-en-abyme.

Fig. 12: Les plages d’Agnès: Varda reflected in a mise-en-abyme.

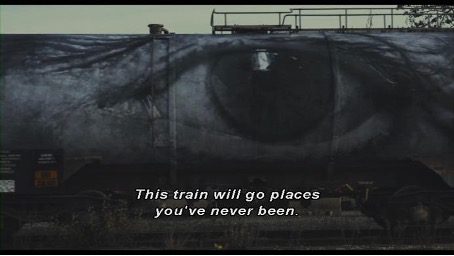

This sense of repetition drawing a self into a coming moment is also evident in Visages Villages. Recalling images of her feet filmed by the director herself in Les glaneurs, JR shoots Varda’s feet in order to enlarge the photograph and paste it onto a tank-car train carriage. More poignantly still, after Varda discusses the painful injections she needs to arrest the deterioration of her eyesight, JR creates an image of her eyes and pastes it onto another tank-car, commenting that it will ‘go places you’ve never been’ (Fig. 13). These moments allude explicitly to the haunting mortality signified by Varda’s ageing body. When the pair visit Henri Cartier-Bresson’s grave, JR asks Varda if she is afraid of death and the director answers, ‘I don’t think so. I think about it a lot. I don’t think I am afraid, but I might be at the end. I’m looking forward to it.’ ‘Really, why?’ JR asks. ‘Because that’ll be that,’ she replies with certainty.

Fig. 13: Visages Villages: Varda’s feet and eyes, enlarged and going places.

Fig. 13: Visages Villages: Varda’s feet and eyes, enlarged and going places.

Conclusion

Of course, the ultimate and inalienable disintegration of the self is denied in the legacy of Varda’s work. There is in the later films an unambiguous process of self-preservation at work, the plotting of the director’s life/narrative for posterity. This sense of writing autobiography is present at earlier points in her work; in her filming of ‘other’ bodies (Birkin, Emilie and Varda’s neighbours in Daguerréotypes [1975], for instance), because these are also, in a sense, depictions of Varda her-self. She consistently complicates notions of biographical portraits, as Isabelle McNeil has noted, as when she declares in Les glaneurs, ‘c’est toujours un autoportrait’ (‘it is always a self-portrait’). As McNeil puts it, this indicates how ‘the subjectivity of the filmmaker inevitably shapes any attempt to document’ (2010: 81). Each of these portrayals is also an account of Varda herself.

Varda’s films, photographs, and installations engage a feminist rhetoric on the gendered, hierarchical positions of subject and other. Through her own body and those of her subjects, she represents the (especially female) self as a nexus formed from multiple features, experiences, perspectives, and performances. The sequences she constructs counter what Jacqueline Rose has described as the sexualising of the female form in filmic tradition: ‘What classical cinema performs or “puts on stage” is the image of woman as other, dark continent, and from there what escapes or is lost to the system; at the same time as sexuality is frozen into her body as spectacle, the object of phallic desire and/or identification’ (2005: 111).

Traditional, patriarchally restrained cinema depicts women as sexualised others for the penetrative, phallic gaze. Yet, even as Varda’s works present the female body naked and fragmented, she denies, inverts, and mocks the masculinised look upon female forms, criticising the sexualising of women’s bodies that restricts them to eroticised parts and disposes of them when no longer youthful. Instead, she reconstitutes the female body as whole, complex, varied, ambiguous, and in flux, resistant to definition as simplified erogenous zones. Her feminist approach is sustained throughout her works when she returns again and again to ethical representations of women’s bodies. As she says in interview, ‘I think I was a feminist before I was born. I remain strongly feminist’ (Barnet 2016: 209). Angela Martin contended in a short piece for Spare Rib in 1978, ‘feminism is big enough to have many voices, many tunes’ (1978: 36). In Varda’s hands, film creates space for such a feminism.

Notes:

[1] Alain Resnais and Marguerite Duras would use the same device in Hiroshima mon amour (1959). Resnais worked with Varda on postproduction for La Pointe Courte and championed it at Cannes in 1955 (Koresky 2023: 24).

[2] The connection with what would become a ‘hallmark’ image in the films of Ingmar Bergman, notably Persona (1966), has also been noted. https://lyssaria.com/2020/07/26/connections-agnes-varda-ingmar-bergman/ (last accessed 5 August 2023).

[3] Images reproduced by kind permission of Ciné-Tamaris.

[4] Perhaps a Vardian allusion to the axe-wielding Jack Torrance in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), with its typed repetition of the phrase, ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,’

[5] English quotations from Réponse de femmes are taken from the subtitles to the Ciné-tamaris edition in Varda L’Intégrale (2012).

[6] It is perhaps more conspicuous in 2023 than it was in 1975 that this multitude is exclusively white.

[7] Images reproduced by kind permission of Ciné-Tamaris.

REFERENCES

Amiel, Mireille (2014 [1975]), ‘Agnès Varda Talks about the Cinema’, translated by Jefferson T. Kline, in Jefferson T. Kline (ed.), Agnès Varda: Interviews, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 64-77.

Beauvoir, Simone de (1988 [1949]), The Second Sex, London: Picador Classics.

Bluher, Dominique (2019) ‘The Other Portrait: Agnès Varda’s Self- Portraiture’, in Muriel Tinel-Temple, Laura Busetta & Marlène Monteiro (eds), From Self-Portrait to Selfie: Representing the Self in the Moving Image, Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 47-77.

Brady-Brown, Annabel (2017), ‘Oh La Varda’, Fireflies, No. 5 (October 2017), pp. 8-17.

Butler, Judith (1997 [1993]), Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’, New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith (1999 [1990]), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York & London: Routledge.

Butler, Judith (2015), ‘Introduction’, in Senses of the Subject, New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 1-16.

Diprose, Rosalyn (1994), The Bodies of Women: Ethics, Embodiment and Sexual Difference, London: Routledge.

Fauvel, Maryse (2005), ‘Nostalgia and Digital Technology: The Gleaners and I (Varda, 2000) and The Triplets of Belleville (Chomet, 2003) as Reflective Genres’, Studies in French Cinema, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 219-229.

Fuss, Diana (1990), Essentially Speaking: Feminism, Nature & Difference, London & New York: Routledge.

Gamboni, Dario (1997), The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution, London: Reaktion Books.

Horner, Kierran (2017), ‘Varda’s Chiasmic Hand: Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (2000), Les plages d’Agnès (2008) and Merleau-Ponty’s intersubjective relation’, Mise au Point, Vol. 9 (June 2017), https://doi.org/10.4000/map.2342 (last accessed 16 March 2023).

Horner, Kierran (2022), Haunting the Left Bank: Mortality and Intersubjectivity in the Films of Varda, Resnais and Marker, Oxford: Peter Lang.

Irigaray, Luce (1994 [1974]), Speculum of the Other Woman, translated by Gillian C. Gill, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Irigaray, Luce (1985 [1977]), This Sex Which Is Not One, translated by Catherine Porter, Ithaca, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lauretis, Teresa de (1984), Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema, Basingstoke & London: Macmillan.

McNeill, Isabelle (2010), Memory and the Moving Image: French Film in the Digital Era, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Prest, Julia & Hannah Thompson (2000), ‘Introduction: Elusive Bodies’, in Julia Prest & Hannah Thompson (eds), Corporeal Practices: (Re)figuring the Body in French Studies, Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 9-14.

Raynaud, Annette (1955), ‘To Give Them to the Other’, translated by Jennifer Wallace, in Peter Graham & Ginette Vincendeau (eds), The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks, New Expanded Edition, London: BFI Publishing (2022), pp. 265-267.

Reardon, Kiva (2018), ‘“Curiosity is a good thing”: An Interview with Agnès Varda’, Cléo: A Journal of Film and Feminism, Vol. 6, No. 1 (spring 2018), http://cleojournal.com/2018/04/11/curiosity-is-a-good-thing-an-interview-with-agnes-varda/ (last accessed 16 December 2022).

Rose, Jacqueline (2005 [1980]), ‘The Cinematic Apparatus: Problems in Current Theory’, in Sexuality in the Field of Vision, London: Verso, pp. 199-213.

Rosello, Mireille (2000), ‘Agnès Varda’s Les glaneurs et la glaneuse: Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady’, Studies in French Cinema, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 29-36.

Silverman, Kaja (1999 [1988]), ‘Lost Objects and Mistaken Subjects’, in Sue Thornham (ed.), Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 97-105.

Spielmann, Yvonne (1999), ‘Expanding Film into Digital Media’, Screen, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 131-45.

Wilson, Emma (2019), The Reclining Nude: Agnès Varda, Catherine Breillat, and Nan Goldin, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Young, Iris Marion (1990 [1980]), ‘Throwing Like A Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility, and Spatiality’, in Throwing Like A Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy and Social Theory, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 141-159.

Films & Art Works

Autoportrait (Mosaic Self-Portrait) (1949), Agnès Varda.

Autoportrait morcelé (Self-Portrait in Pieces) (2009), Agnès Varda.

Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962), dir. Agnès Varda.

Daguerréotypes (1975), dir. Agnès Varda.

Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les glaneurs…deux ans après (The Gleaners and I…Two Years Later) (2002), dir. Agnès Varda.

Jane B. par Agnès V. (Jane B. by Agnès V) (1988), dir. Agnès Varda.

Lions Love (… and Lies)/Lions Love (1969), dir. Agnès Varda.

L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008), dir. Agnès Varda.

La Pointe Courte (1955), dir. Agnès Varda.

Portraits brisés (2010), dir. Agnès Varda.

Réponse de femmes: Notre corps, notre sexe (Women Reply) (1975), dir. Agnès Varda.

Sans toi ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), dir. Agnès Varda.

The Shining (1980), dir. Stanley Kubrick.

Trio de neige (2010), Agnès Varda.

Varda par Agnès (Varda by Agnès) (2019), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les veuves de Noirmoutier (The Widows of Noirmoutier) (2005), dir. Agnès Varda.

Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017), dir. Agnès Varda & JR.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey