Essential Work: An Interview with Civil Rights Photographer Doris Derby

by: Heather Diack , June 25, 2022

by: Heather Diack , June 25, 2022

Doris Derby (11 November 1939 – 28 March2022), was an administrator, professor, documentary photographer, speaker, and author who earned her Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College in New York, and Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Illinois. She was one of the organisers of the March on Washington in 1963. After teaching elementary school in Yonkers, New York, Dr Derby joined the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi to work with grassroots organisers in Black communities and take steps to impact societal change.

As a ten-year Civil Rights Movement veteran (1962-1972), her work has been recognised in several publications, documentaries, and online publications. Dr Derby is a contributor to Hands on the Freedom Plow, a book that features 50 SNCC women’s contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. Her book, POETAGRAPHY: Artistic Reflections of a Mississippi Lifeline in Words and Images: 1963-1972, contains a combination of the poetry and documentary photographs she created while working in Mississippi. Her forthcoming book is PATCHWORK: (PPP) Paintings, Poetry and Prose; Art and Activism in the Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1972. An extensive volume of her photographs, A Civil Rights Journey by Doris Derby, was recently published by MACK Books (2021).

From 1990 until her retirement in 2012, Dr Derby was Georgia State University’s founding Director of African American Student Services and Programs, and an Adjunct Associate Professor in the Anthropology Department.She lived in Atlanta with her husband, retired Army Veteran and actor, Bob Banks. In 2011, Dr Derby was honoured with the Georgia Humanities Award by the Governor of Georgia for her work and photographs depicting the life of struggling Americans who defied the post-emancipation status quo brought about by political, economic, social, and cultural domination and exploitation. Her images have been shown in numerous museums, galleries, universities, and websites including the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, the Krannert Art Museum in Illinois, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, the Rose Library of Emory University, in Atlanta, the Art Gallery of Jackson State University, the Turner Contemporary Art Museum in Margate, England, the Photographers Gallery and the Website of Apollo Magazine, in London, England.

In April 2021, I had the privilege of speaking with Dr Doris Derby. The following interview is an edited transcript excerpted from our many hours of conversation.

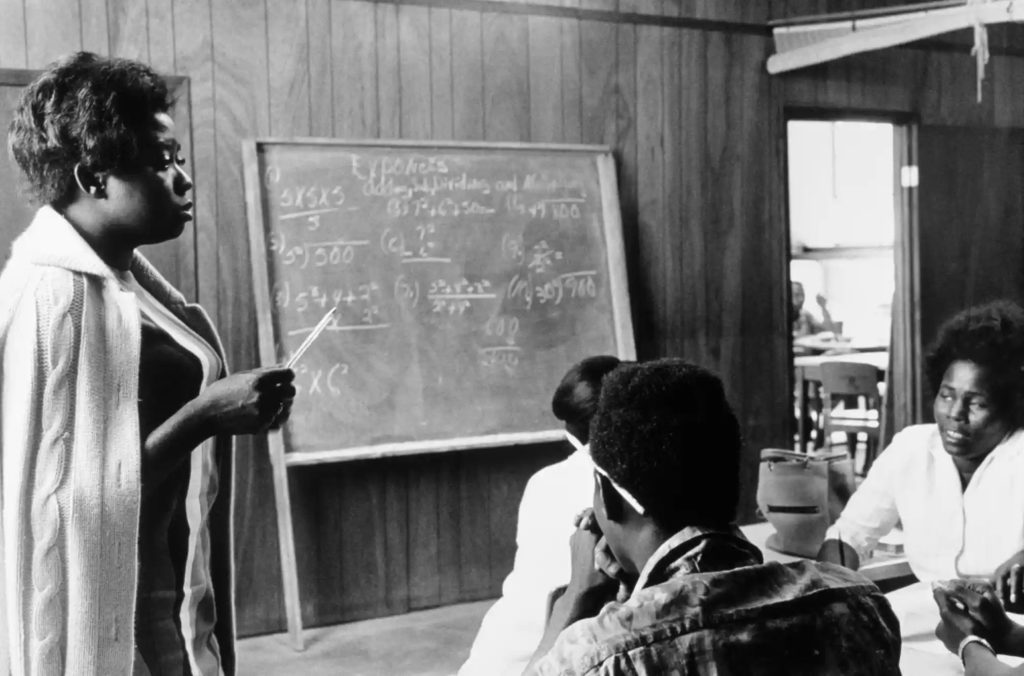

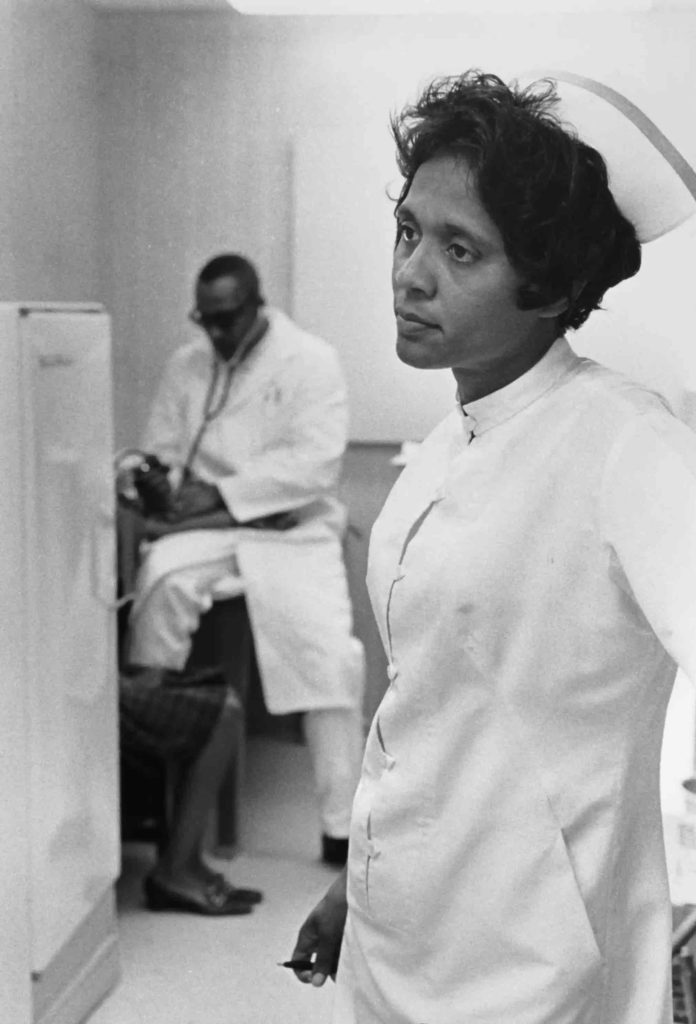

After being recruited by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the early 1960s, she committed herself to a life of art and activism, using photography as an instrument of community-building. Her photographs of the Civil Rights Movement and beyond depict the lived experiences of Black people amidst the oppression and inequities of race relations in the Southern United States. While based in Mississippi during the 1960s and early 1970s, Derby took thousands of photographs, documenting the work of voter registration, political organisations, sewing collectives, vegetable growers’ collectives, health care workers, math teachers, and many others. In other words, the crucial scenes of community organising and mobilisation that remain too frequently under the radar of most iconic, high-circulation images of the Civil Rights Movement. Dr Derby’s thoughtful, humanising, and personal pictures speak volumes about the necessity of intersectional awareness and advocacy in the name of change. They also emphasise the essential role of women. Inspired by the visual lyricism of Roy DeCarava, Gordon Parks, Käthe Kollwitz, and others, Derby developed her own unique blend of photojournalism and art, often through the intimacy of portraiture.

In contrast to the climactic and violent images of protests, funerals, and murders that dominated the front pages of popular media as the Civil Rights Movement unfolded, Dr Derby’s photographs intentionally spoke directly to Black communities about the power of Black agency. In this interview Dr Derby and I discuss the formative influence of her formidable family, her photographic practice, and her career as an educator, anthropologist, photojournalist, painter, and poet. We touch on the politics of representation, social justice, and the importance of recognising essential work, even within seemingly ordinary acts.

*

Heather Diack (HD): Let’s start at the beginning. How did you become interested in photography?

Doris Derby (DD): Well, my father was a photographer and he regularly photographed whatever his family was doing, and other people that he knew. He had a really nice camera, and he would take the pictures and then transfer them to slides. Then, using a slide projector, he would show the pictures at a family event. I actually have his slide projector and screen. My sister has his original camera. When we were young my father gave my sister and I each a brownie camera so we would take pictures, and later my brother, who [was] born nine years later, got a camera, so we all took pictures.

HD: So, before you started working with SNCC, you were already taking pictures, but did taking photographs become more important to you once you joined the Movement?

DD: Well, I don’t say that was more important because it’s always important in that respect, to document family. Don’t forget, as an undergraduate student I was also an anthropology major, and as a cultural anthropology student I was interested in people. I was interested in cultural anthropology, not, you know, in terms of numbers and how many people did this, and that—I was interested in it from more of a grassroots point of view of people in communities, what was happening, who they were, what they are doing, what are some different aspects of people living in some particular situation.

All I did in the Movement was not something that was, at the core of it, new, or starting in the 1960s. In the South, the environment was different, but my motivation and my impetus for doing what I did was from when I was young. When I was in elementary school, fourth grade, I realised that we lived in a community that was predominantly white, predominantly Italian. But it had a sprinkling of other ethnic groups, and we had a sizeable Black community … We got along with everyone as an integrated community.

My girlfriends and I, we would go to the movies every Saturday. We would be looking to see if there were any Black people in the movie. Hardly ever, if ever! There was maybe a native in a Tarzan-like movie, or a maid or a butler. This was not something very impressive, but, nevertheless, we would say, ‘oh there’s a Black person, look!’ On the other hand, as I was telling you, my father documented our family life. And we had oral history. From my grandparents on both sides, we had a very illustrious history of achievements and struggles that our family members had gone through. My grandparents kept newspaper articles of everything that occurred that related to them or their community. My paternal grandparents were from Boston, Massachusetts. My maternal grandparents married and lived in Bangor, Maine, a predominantly white town. My maternal grandfather was from Virginia. And my maternal grandmother was from the Virgin Islands, and I think born in Haiti, as she spoke French as a mother language.

HD: You come from such a big family, and as you’ve described, there were so many family members who went after their ambitions, who were creative and inspiring, setting an example for you. With your studies in anthropology and your interest in art, how did those things really come into being in your adult life?

DD: To give you some background, before I went to work in SNCC, all of this activism was already formed. The environment and the struggle were more pronounced in many ways in Mississippi, but my father faced discrimination in the North, so I knew about discrimination. When I was growing up, I knew about the fact that we didn’t have any Black visual images. We used to listen to the radio, being very excited listening about Jackie Robinson in the Dodgers being the first Black man playing baseball, or Joe Louis, a Black fighter. I didn’t see many Black visual images, but I knew that we had them. Growing up in the Bronx, I also spent time in Harlem, and I experienced the Black community around the Apollo theatre, the liberation bookstore, the Schomburg collection at the public library, the YMCA, and other historical Black places.

HD: In Harlem, you were exposed to these various Black institutions and sites of creativity. You’ve described a large family network and the lived experiences of each of these individuals who you didn’t see represented in larger media, for example, when going to the movies or finding them in the so-called popular culture, right? So, you yourself begin to take photographs. You begin creating the archive documenting the history of what you had around you. One of the things that’s so notable about your photographs, is how they document meaningful moments, but also everyday moments. If you had to describe your approach to taking pictures, to photography, would you say that it comes out of the formative family relationships that you’re describing?

DD: I think, yeah. I’m formed by family and community. And church, and the arts.

HD: The difference between New York and then coming down South must have been quite jarring on many levels.

DD: Well, you know when I went from the Bronx to Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, you had the Main Street. And you know, the Main Street had the biggest stores, and hotels and certain places that Blacks couldn’t go. Then you had another street coming off of Capitol Street, which was the main Black street, primarily Black businesses. It had clubs and grocery stores, it had law offices, dental offices, doctors’ offices, churches, the YMCA, and houses on the little streets off of the Main Street. This was called Farish Street, the heart of the Black community.

But when you went to the rural area, that’s where segregation, racism was blatant and very oppressive. And part of the blatancy was that Black people didn’t have any kind of stores, hardly ever. You have large numbers of majority Black communities, and they were held back, didn’t have much. You had sharecropper plantations, former slave plantations. So, that is the physical environment. I didn’t go straight from New York to the rural area. But later, within a month of my arrival, I went with some SNCC workers. We tried to get the people to vote, to do this, to do that. But it was quite different from the city. I just learned how violent it was there, how destitute people were, the poverty was horrible to witness.

HD: You’ve described part of your time in Mississippi as a combat zone, and you refer to yourself as a veteran, alluding to the widespread violence and oppression in the South. What role did you see photography and visual culture playing in that, in the struggle?

DD: Even before I left New York, I was involved in producing visual art. I wanted to see positive visual images, and I started to say, ‘I’m going to find visual artists and photographers who are making positive Black images. They could be struggling, they could be happy, or they could be doing what people do, families, whatever. I want to see that, I want to see who’s doing what, and I want to be able to do it myself.’

Perhaps in order to show other people, whether it’s in books or whether it’s in movies, I want to know where it is so that I can tell people ‘here’s where this information is. Here’s who’s doing this.’ And you can get to know these people, because in documenting, doing great images and putting them somewhere else, people will [come to] know about them.

HD: Are there particular artists from that time whom you see as your influences?

DD: So yes, I knew Tom Feelings and his work, and there was Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Ernest Critchlow, and Norman Lewis. I knew about them, one way or the other, because they were based in Harlem. Tom Feelings was younger, and also, I talked to George Wilson. I mean those are some of the artists I came to know. James Van Der Zee. Roy DeCarava. And Gordon Parks. I met the Tuskegee photographer P.H. Polk, from Bessemer, Alabama in 1965, when I was working at Tuskegee University for a few months. He was very nice and friendly, and we had good conversations. I went to his studio from time to time, talked to him, saw his photos and the artwork and sculpture he had displayed in his yard. It made a lasting impression on me. I always wanted to have artwork in my yard. Mr. Polk was a painter before turning to photography, so was Roy DeCarava, and so was I, as will be seen in my upcoming second book, Patchwork: Paintings, Poetry and Prose.

Often when I look through my camera lens, I am thinking about how that image would look as a painting. Even though my paintings have never been made from a photograph, rather from memory and what I see, a mixture of image sources, and the spirit from my mind’s eye. So now another person that I would say influenced me was Käthe Kollwitz. I really liked her work, which I came across when I was in New York, and I just loved her depictions of women and children and families in times of war and poverty.

HD: This leads to my next question, which has to do with your focus on women, the role of women in the struggle, and the way that you capture that. A lot of your photos are close-ups of individuals. For example, the nurse at the Tufts Delta Health Clinic: it’s such a beautiful portrait. It’s very pensive. And there is another one, where you have a civil rights attorney crossing the street. I’m wondering if you could say something about the way you chose to photograph them. These portraits possess a certain kind of intimacy that both you and Käthe Kollwitz have in your images, between you, the creator of the work, and your subject.

DD: Here’s the thing. As a painter looking very closely at the image over and over again, I can make it the way I wanted you to see it. When you’re painting, you’re going to keep going and looking back and forth. Maybe you think it looks like it’s finished? It’s not really finished, there’s something else you want to put in. And you’re thinking about it and you’re creating, images created from my head, from my heart, from something that I saw that I say, ‘I’m going to paint this.’ When I was taking pictures, when I had time to take pictures, I was taking them fast. But if there are people there and I got more time to take the picture, to think about it, I am looking at it more as an image for a painting. I’m thinking, ‘Oh, this might be a painted picture that I could make’. It has that spirit in it. It’s not just a picture of somebody that I’m taking you know: it’s capturing the kind of things I want to convey through a painting, that takes a lot more time and study. Thinking about it, in looking at the person, what is the essence of what they are trying to tell me? How does this picture depict them, their situation, and their spirit? I wanted to depict that about women and children, men too. Sometimes I know the person, sometimes not.

Don’t forget, I went to other places before I went to the South. I lived on a mission in a Navajo Indian reservation in Farmington, New Mexico in 1959, and I saw what was happening to the American Indian population, how they were destroyed. The children were brought to the mission often because their parents got drunk, got arrested, put in jail, or were hurt some way. We would go out during the week to teach Bible school to the kids. We had Indian kids, we also had migrant Black children from Texas. I was young, I met some young Navajos and talked a lot with them. I saw the sweat lodge. I didn’t go in it, but I was there. I watched the sunset, so some of my paintings, you know, have a sunset. Because I remember so vividly, people were poor, very poor, suffering, but keeping their culture and history alive. The sunsets were beautiful, just as their culture, such as their crafted turquoise jewellery.

That was in 1959. And in 1960, I spent the summer in Nigeria in different ethnic communities. Nigeria didn’t become independent from the English until 1960. I won a scholarship to go with this group called the Experiment in International Living, based in Putney, Vermont. I was the youngest one in the group, the only undergrad. The NAACP gave scholarships, and I got one. On the way back, we went to Rome, Italy, and Paris, France. So, I have around a thousand pictures of my work, my stay, in Nigeria, I have some beautiful pictures. And they still hold up, in colour and in black and white. There was such diversity there, great art, music, dance, dress, traditional culture. They treated us with greatness.

HD: Those experiences in New Mexico and Nigeria must have been very influential.

A number of your photographs are particularly community-oriented, documenting acts of community. We’ve talked a little bit about how your individual portraits show a tremendous amount of sensitivity and respect for the people that you’re photographing. Similarly, those are aspects of your photographs of groups, whether it’s the vegetable cooperative or people working in a classroom. With those particular images, did you see them as documents to help mobilise people?

DD: Well, I guess, the intention was two- or three-fold, you know. I was documenting positive images of us doing a wide variety of things that we need to do as a community, as individuals, to say, ‘this is what we’re about.’ Positive, you know, trying to do things for our family, whatever is needed—and, as you know, my father did so many things for his family and community. Through his own efforts for our family, I could see other families who were doing the same things. They were planting food and harvesting, they were doing happy things, taking us to parades or to other things. So, these are things which people do. You don’t have to have all these material things. Being involved in voting and other aspects of good citizenship, these are activities that people do in the community, these are things that I saw at the time, so that’s what’s happening—let me take pictures of that. But this shows that Black people are doing what other people do, or they want to try. It may not be as polished. That’s my whole story: we want to show that in the books.

HD: I wanted to know your thoughts on the relationship, in your experience, between the Civil Rights Movement and the women’s movement. Do you feel that Civil Rights influenced the feminist movement?

DD: It definitely did. There were a lot of a young Black and white women involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Many white women were in SNCC and this started expanding and turning a certain way. Some of the Movement people were talking to white SNCC members, saying that they have to organise in the white community. Because it’s not just the racial situation in the Black community, it’s the white community that needs to have more organising, and as people in the white community want to do better, there’s a lot that needs to be better. So, you had some of the whites going back to their hometowns, to their communities, to start organising the white communities and you also had some women who felt that there wasn’t enough going on for women’s situations and status. Some felt that some of the men were so much more in the forefront. They didn’t like them being ‘macho.’

But yeah, when you bring to light how one group is oppressed, another group that’s oppressed says, ‘well, I’m oppressed. And I need to make some difference, I need to change things.’ White men were oppressing everybody, so they needed to do better, they needed to be told about what was going on.

Then you had also the gay rights movement, and then the disabled people and the aged, like we’re being held down. You had many other movements that came to being, came more to the forefront after seeing the Black Civil Rights Movement. It was about people not being held down because of one thing or another. We are human beings, and we need to be free, we need to be able to determine our own destiny and to use talents in the best way that we can. You know, that’s all, to be able to accomplish and be happy. Not being exploited.

HD: On a related note, given the recent surge of visible activism in the United States, especially during the past year (2020-2021), and the increasing recognition of the need to acknowledge essential work, the ordinary things people do every day, I’m wondering if you see connections between the present and the impetus of your earlier work?

DD: Definitely. The essential workers are the ones that are doing so many of the jobs that are needed, and they don’t get rewarded for that. Essential workers definitely. That was brought out in another way to say, look, the people here, they’re doing their job, they’re doing a good job, taking care of us, and they need to be paid. Much better than what they do. So many of them are getting sick, they’re taking chances. Why are some people getting so much money? For so many things—millions of dollars! They don’t need it, just wasting it, squandering it. While others are working hard every day just working to make ends meet.

HD: And, of course, looking at essential work we can see how disproportionately it is of women and women of colour, who should be paid more, who should be respected more for their service, for their essential work.

DD: Yeah, all the essential workers, men and women. You know when you go to the hospital you see people cleaning and they’re holding your hand, it’s like you may be in a life-or-death situation. Pay him. Whatever they need. Pay people more. You know they go, get training, somebody who learns how to be a good cleaner and knows not to use this kind of powder or that kind, all that comes from experience. So, people should be paid for their experience. Definitely they need to be paid more.

HD: And do you still think that visual images can play a role in that kind of activism and mobilisation?

DD: Well, I think it is because we are seeing so much of it on TV. And with the virtual now, I’ve been able to show my work to many people across the country that would not have been able to be at an exhibition in person. And there have been more panel discussions about the work. And that kind of thing is important. The visual images, for example, the still photographs of the essential workers, are certainly missing. But the increase in virtual interviews and conversations bringing groups of people together to tell this story helps. All of this is important. To say, you know, we need more equity.

HD: So, here’s one more question—that is perhaps too broad—but, if you had to say which photographs from your archive are the most meaningful for you, would you be able to?

DD: I would not. When you say, ‘what are the most meaningful?’ I would have to say it’s not one or two. I am working on a new book that’s going to be published by MACK, and we’re in the process of selecting photographs and talking about them. We want to use a handful to say, ‘this is what the book is about.’ A minimum of ten would have to be out there to show the variety of photographs, and the stories that are being told within the broad framework of those photographs. If I give you a photograph, I say okay, one photograph of the people on Farish Street. That’s one photograph that’s going to open a whole door to maybe 500 photographs. And then let’s take another photograph of the Tufts Delta Health Clinic, the Committee for Civil Rights Medical Initiatives, so right there that one would open up the door to several hundreds more.

Then I’ll say that we’ve got another one [about] the right to vote, the push for voting legislation to be passed. I’m going to tell you about the poverty in the Mississippi Delta where the majority of Black people were living—that’s several hundreds of photographs. And then I might tell you about the Head Start Program. This right here, is going to open up to several more photographs. Then you have the shootings, and the murder of two young men at Jackson State University in 1970. I’m going to show you a whole set of photographs related to the hearings. I’m going to show you pictures of the funeral and the protest, the burial. I’m not going to give you one or two pictures. I’m not going to do what the newspapers did—a picture here and there. Not just a big picture that shows this big moment, and that’s the end of it. I would say, a minimum of ten pictures. I’m going to show you a picture of the cooperatives, and that’s going to open up a door a to several more stories. I’m going to tell you about the farmers in Lafayette, Louisiana and their farm cooperative. That’s going to open doors to show their life: how did they live, what did the farm children do? How did the children learn about what their parents do, how did the people come together and have a warehouse where they bring their raw materials, their vegetables and get them ready for produce sales? What about these children—I’m going to show you all these pictures, different children, how they look and how they feel. So, I can’t give you less than 10. And that’s really pushing it.

*

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey