Entropic Creativity: Agnès Varda’s Early Publications & France’s Post-war Film Ecosystem

by: Tim Palmer , November 7, 2023

by: Tim Palmer , November 7, 2023

Introduction: A New Agnès Varda Emerging

Agnès Varda needs a more accurate origin story—an account that considers her formative situation in France’s post-war film ecosystem alongside her own creative emergence. On- and off-screen, right from the start of her career in the 1950s, Varda was a brilliant, connected individualist. But our inherited Varda historiography skews us away from the actual post-war trade she entered, treating her initial output—especially her first shorts—and the cultural conversation she joined, as at best preambles, at worst, marginalia. Respondents shunt Varda instead towards the Left Bank of the nouvelle vague in the 1960s, with all its attendant assumptions about auteurism, the pre-eminence of fiction feature productions, and, most perniciously, the male-oriented values of a movement with only two women associates, one of whom, Paule Delsol, is still ignored by critics and historians (Palmer 2017). Delphine Bénézet, in her essential Varda study, grapples with these issues, arguing that Varda was ‘ahead of the technical and aesthetic changes associated with the New Wave years later… [and Varda’s] alternative approach to filmmaking make[s] her a special case, or “cas d’espèce” that needs to be fully understood and re-evaluated’ (2014: 3).

To address these entrenched historiographical problems, this article reframes Varda on two fronts. Firstly, it restores Varda’s initial output to where it belongs: the creative ferment of France’s Fourth Republic moving image ecosystem, 1946-1958. This era saw France’s production sector diversifying and rebuilding from scratch, based on variegated commissioned media, shorts and micro-features, essayistic experimentations made by a vanguard of (historically neglected) professional women, and filmmaking marked by an expansive yet ambivalent social conscience. In this context, as our new micro-history reveals, Varda’s post-war arrival, and passage into the 1960s, was a personal-professional breakthrough, but also a culminating synthesis of a period that has been represented too long via inaccurate New Wave polemics. Secondly, to explore more fully Varda’s post-war backstory, this article broadens our grasp of Varda’s initial work, connecting her short films to her photography and, in particular, analysing Varda’s long-overlooked authorship of books. While Varda published photographs in multiple 1950s Théâtre National Populaire (TNP; France’s leading national theatre company) collections, as well as in volumes such as Anne Philipe’s Le Temps d’un soupir (1963), she also, most crucially, spent the late 1950s writing a single-authored monograph, published as La côte d’azur (1961), a text that has since become vanishingly rare. An intertext to Varda’s corresponding film, Du côté de la côte (Along the Coast) (1958), this book demonstrates Varda’s essayistic artmaking and stylistic professionalisation, including craft facets new to the record, notably her melancholic poetry. In sum, not only do Varda’s book ventures showcase the variegated multimedia inherent to her emergence, and later work, but also how her practice hinged upon applied cinephilia, with multimodal affinities for cultures canonical and evanescent, traditional, and experimental. Above all, as we will see, it is the creative trope of entropy—production and destruction poised in proximate dichotomy—that underwrites and connects Agnès Varda to the post-war film culture whence she came.

Varda’s Cultural Nutrients: A Communal Micro-History of Post-war French Media

Let us jettison, to begin with, the critical baggage foisted upon us regarding France’s post-war media culture, the biased sample of commercial feature film analyses advanced by figures such as François Truffaut (1954: 15-29). No more Tradition of Quality epithets, therefore, but rather a better-faith model of a post-war moving image ecosystem that was, in fact, designed to foster media citizenship, to advance social and historical engagement through cinema, to enfranchise a new generation of filmmakers, journalists, teachers, filmgoers, and participants of all kinds. We can take our cue from Robert Favre le Bret, Secrétaire Général of the Cannes Film Festival’s organising committee, as it started operations in 1946 after a seven-year hiatus. Le Bret’s call to action came within a wide-ranging industrial compilation—part diagnosis, part prognosis—published in 1946 as Le Livre d’or du cinéma français. Its analyses spanned everything from shorts to exhibition, amateur filmmaking to commercial enterprise, genre studies to film education and criticism, with contributions from post-war notables as diverse as Jean Cocteau, Lucie Derain, and Jean Painlevé. In this frame, le Bret rallied for a cinema that would

take the initiative to renew among nations the spiritual chain of civilization … cinema has earned its place in the combat; it’s a weapon of knowledge; a discerning and magnificent eye; it can help discover the deepest humanity … by constant research … through the creations of this documentary art. (in Pascal 1946: 17-18)

As utopian as le Bret’s ideas might sound, his principles broached conceptual pragmatics that would galvanise a generation to follow. The tenets are especially visible among non-traditional essay filmmakers, people like Nicole Vedrès and Yannick Bellon, whose programmed berths at le Bret’s Cannes event instilled creative response among peers in the field. Note, too, le Bret’s climactic point about nonfiction and fiction modes, the hybrid fusion of documentary with art.

How, then, did le Bret’s discerning knowledge weapon cinema manifest, at Cannes and elsewhere? What were its core practices? And which signature texts would nourish Varda’s career after the mid-1950s? A useful point of entry is to create a post-war counter-canon, an alternative to the ‘ten or twelve’ films Truffaut claimed to ‘merit retaining the attention of critics and cinephiles, and so the attention of Cahiers’ (1954: 15). This yields a partial, but more inclusive, cultural trajectory across the next decade, providing stylistic backdrop, and direct cited acknowledgement, to Varda’s fledgling work. In doing this we can also reset certain prejudices, again traceable to Truffaut, allowing us to represent more vigorously the post-war film ecosystem’s ground-breaking works. Let us therefore:

Recognise women practitioners as contributing agents alongside men;

Set short films beside mediums and longer texts;

Hold commissioned or trade-initiated texts in the same regard as commercial features;

Value communal authorship and piecemeal or curtailed careers as equal to those of more longstanding directors;

Expand our textual coverage to acknowledge the post-war influx of Franco-African filmmakers;

Elevate essay films, or non-traditional nonfiction hybrids about social events or ideas, to the same rank as conventional fictions about individualist (male) protagonists.

In sum: overhaul the traditional criteria of (post-war French) film history, the usual tropes of cultural worth. From this comes a new, contingent lineage of cross-pollinating cinema—some films that are iconic, some effaced and unjustifiably obscure—that collectively takes us to Varda, whose work becomes central, rather than outlying, within France’s cultural output:

Paris 1900 (1947): Nicole Vedrès (Arguably France’s key post-war initiating film source)

Goëmons (1947); Colette (1950): Yannick Bellon

Le Sang des bêtes (Blood of the Beasts) (1948); Hôtel des Invalides (1952); Mon chien (1955); Le Théâtre national populaire (1956); La Première nuit (1958): Georges Franju

Afrique 50 (1950): René Vautier

Avec André Gide (1951): Marc Allégret

Guernica (1951): Alain Resnais and Robert Hessens

Les Statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die) (1953): Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Ghislain Cloquet

Afrique sur Seine (1955): Mamadou Sarr and Paulin Vieyra

Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog) (1955); Toute la mémoire du monde (All the World’s Memory) (1956): Alain Resnais

Dimanche à Pékin (Sunday in Peking) (1956); Lettre de Sibérie (Letter from Siberia) (1958): Chris Marker

Django Reinhardt (1957): Paul Paviot with Chris Marker

Ô saisons, ô châteaux (1958); L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958); Du côté de la côte (Along the Coast) (1958): Agnès Varda

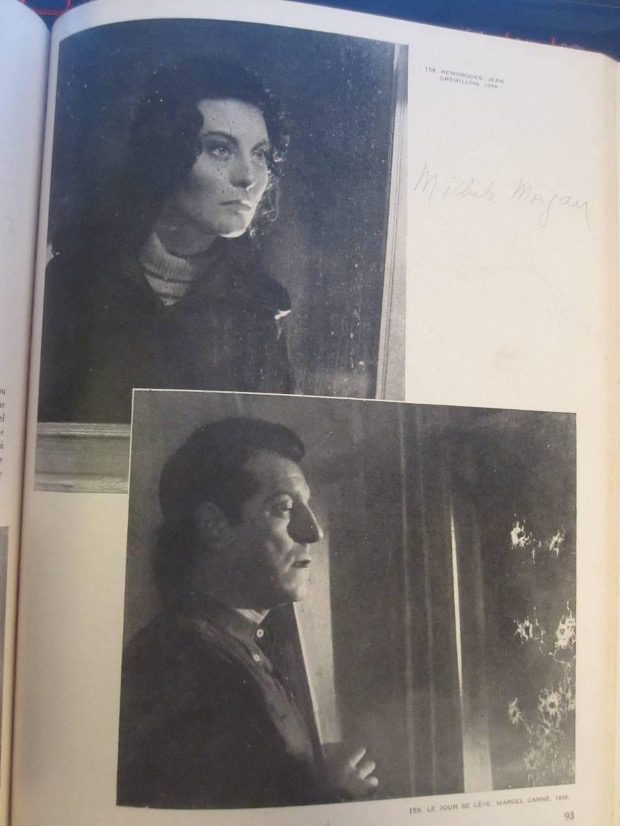

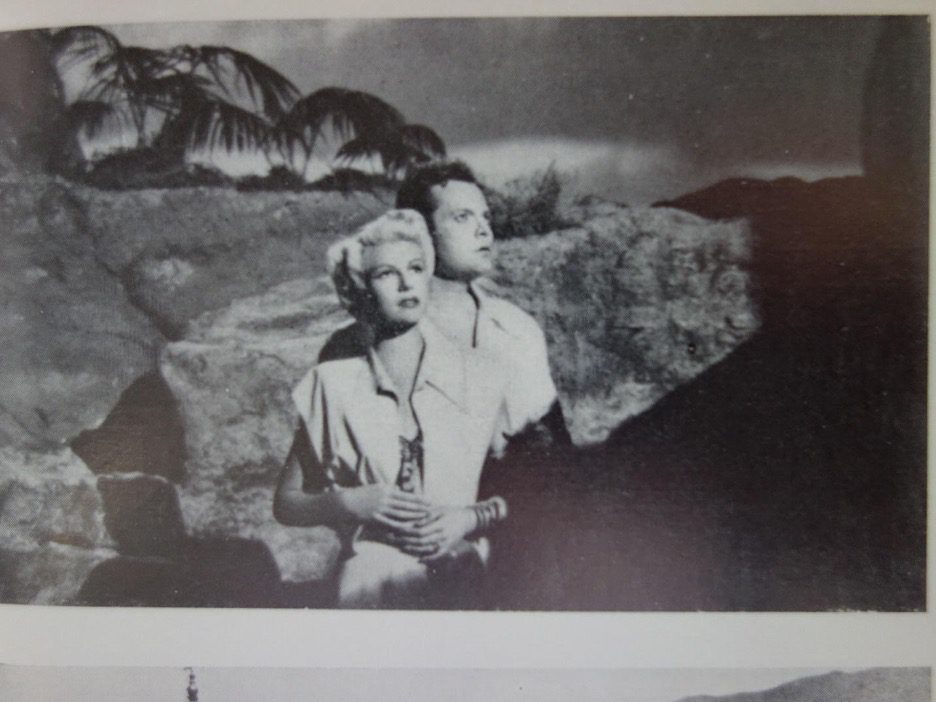

This screen itinerary foregrounds three main nodes of rejuvenating post-war practice, all of which were essential stimuli for Varda. First, there is the underrated yet headlining impact of Nicole Vedrès—journalist, critic, filmmaker, radio and television writer, scholar of fine arts, whose lifelong advocacy for media literacy is finally attracting overdue attention (Allain 2014, Liandrat-Guigues 2018, Russell 2018). Among Vedrès’ many contributions, equal in significance to André Bazin’s, the impact of Paris 1900, her proto-essay film, looms largest. It debuted at Cannes in September 1947, won the Prix Louis Delluc three months later, then, crucially, stayed in release across France (and internationally) for nearly a decade, hailed by Alexandre Astruc as a model for aspirant essay filmmakers (Palmer 2021: 125-126). Commissioned by Pierre Braunberger, whose traditionalist documentary approach Vedrès quickly superseded, Paris 1900 interwove footage from home movies, newsreels, fiction shorts, actualities, and Vedrès’ own directed inserts, to create a dazzlingly disjunctive portrait of France’s course from Belle Époque to World War I. In terms of direct descendancy, Vedrès hired and trained Resnais to edit her (literal) mounds of found footage; Resnais would later mentor Marker and Varda herself; Paris 1900 is duly referenced on-screen in Du côté de la côte (Palmer 2022: 84-87). More broadly, Vedrès popularised a collage aesthetic, media-making as an assemblage of fragments, a self-reflexively mediated, portmanteau treatment of an era, a place, and the humans found there, both as individuals and en masse. With her typically acerbic wit—similar to Varda’s own—Vedrès assessed her interventions as, ‘Once again, the epoch moved in our hands, it turned red, it took a train… and we could never catch up with it’ (1948: 4). And alongside Paris 1900, equally influential on Varda’s methods was Vedrès’ innovative 1945 pictorial film history, Images du cinéma français, an associational visual catalogue, distilled from the Cinémathèque Française archives, in which Vedrès used paired film stills to chart dichotomies of expression, including genre (‘Adventure,’ ‘Terror’), stylistic abstraction (‘In pursuit of forms’), and, perhaps most provocatively, renditions of gender on-screen (‘Men and women’) (Fig. 1). Such was Vedrès pioneering impact, as filmmaking-essayist-historian, that Lucie Derain acclaimed her ‘beguiling’ and ‘analytical’ breakthrough career, media work that ‘restores the raw value [of cinema design], at once simple and quasi-naïve, through the skilled and subtle oppositions of clichés’ (1946: 252).

Fig. 1: Nicole Vedrès’ ‘Hommes et femmes’ gender analysis, pairing a still of Michèle Morgan in Remorques (Stormy Waters)(1941) alongside Jean Gabin from Le jour se lève (Daybreak)(1939), in Images du cinéma français (1945). [1]

Fig. 1: Nicole Vedrès’ ‘Hommes et femmes’ gender analysis, pairing a still of Michèle Morgan in Remorques (Stormy Waters)(1941) alongside Jean Gabin from Le jour se lève (Daybreak)(1939), in Images du cinéma français (1945). [1]

Our second film ecosystem node is the complex of essayistic parameters, some initiated by Vedrès, that became norms, permeating the cultural groundwater of post-war France, thereafter suited for Varda’s own preoccupations. This was, as Antony Fiant and Roxane Hamery observe, a ‘production panorama… [of] alternatives, intersections, hybridizations’ (2008: 9). Traced through—and beyond—our post-war counter-canon above, these films were socially engaged, fixated upon representations of cultural memory, and, above all, steeped in melancholic creativity. More concretely they tended to be: highly self-reflexive, multimedia mixtures of actuality and fictional-editorial mediations; commissioned texts, initiated by gatekeepers of cultural history such as museums and journals; stylistically disjunctive, with ambivalent or caustic image-sound relations; and anti-dogmatic or dissident treatments of power and marginal peoples. As Nora Alter and Timothy Corrigan argue, post-war France was a motherlode of such essayistic habits, frequently hinging on the representation of stream of consciousness or thought itself. For them, Astruc was the era’s major respondent, whose ‘filmed philosophy’ and ‘caméra-stylo’ notions coalesced in a 1948 pledge that ‘the cinema being born will be much closer to a book than a performance; its language will be that of the essay, poetic, dramatic, and dialectic all at once’ (in 2017: 9). [2] On-screen, in this context, an unorthodox range of subjects, editorial positions, and rhetorical focal points became refrains. Textual centrepieces included: evocative buildings or urban structures (Blood of the Beasts, All the World’s Memory); travelogues that generate speculation more than stable knowledge (Letter from Siberia); a person’s recollections offered as a shifting subjective prism (Colette); history rendered via detritus, material debris and discarded relics (Statues Also Die, Night and Fog); and people of culture surveyed via disparate surrounding groups (Django Reinhardt). This, in sum, was the creative composite that was conducive to Varda’s work, shaping her screen sensibility.

The third main current of France’s post-war film ecosystem underwrote all of the preceding, an absolute bedrock of modern French cinema. This is applied cinephilia, the instantiation of practice based on critical study, an engagement with film history, via instruction and mentorship, as the active means for filmmaking evolution. After 1946, at le Bret’s Cannes, aligned to new post-war institutions like UniFrance (global film distribution coordinators) and the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC, France’s prestigious national film school), French applied cinephilia mobilised en masse. Tracing this process of conceptual pragmatics, treating film history as a fluid interchanging continuum, rather than the preserve of isolated elite (male) maker-geniuses, allows us to avoid the pitfalls of the auteur theory, denounced by Isolde Standish for ‘its inability to fully explain the production of a distinct body of films by a diverse group of individuals within an historical moment’ (2011: 148). On applied cinephilia, conversely, we should listen to Varda herself, defining her 1954 coming-of-age, as Resnais transmitted to her what he had learned from Vedrès, gleaned from Paris 1900, alongside the myriad films in release around them. Varda proclaimed:

When you edit … images and various references come to you completely naturally. I ended up thinking that I should see what he [Resnais] was talking about, and I started going to the cinema, to the Cinémathèque, to see new releases, to buy film journals … And I realized that I wanted to be a cinéaste (in Fieschi & Ollier 1965: 45).

The same applied cinephilia equation continues today; it is often articulated most fiercely by women or non-traditional filmmakers who see their professional progress as fugitive. In 2023, for example, Alice Diop, in conversation with her mentor, Claire Denis—whose work she always consults while in pre-production—stated, ‘What I mean is that you can borrow so much from the work of someone who speaks to you and penetrates you that you feel like you’re making films that expand something you saw in that film’ (in Wheatley 2023: 42). To this applied cinephilia dynamic—innovation and implementation as textually communal, an overlap creativity—we can now turn, analysing Varda not only as a consummate post-war filmmaker, but also as a publisher of books and visual media of all kinds.

Écriture-Ciné: Varda’s Post-war Publications

With our revisionist postwar micro-history in place, Varda (re-)emerges as an applied cinephile citizen within that history, particularly via her process of decision-making on- and off-screen. Two recent new conceptions of Varda’s career offer us specific revisionist points of entry here. Colleen Kennedy-Karpat isolates Varda’s ‘sustainable legacy,’ renewing our focus on Varda’s many artistic interactions, casting her career not in terms of ‘fixity or stasis’ but through the ‘transformative power of preservation as a process’ (2022: 3). Alongside that reframing cue is a related claim about intertextuality by Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, highlighting the crux of ‘Varda’s taste for proliferating forms’ (2022: 85). Clearly, this connective tissue of Varda’s work, her abiding affinity for multimodal crossover, needs further investigation. But rather than veering towards Varda’s later essay films and art installations to pursue this, the usual critical instinct, we should head in the opposite direction, turn Varda’s career on its head, finding fruitful, even defining evidence among her linchpin 1950s work. To do this, we need to reappraise Varda’s formative outputs, putting a gallery of hitherto forgotten works, especially her post-war publications, their images and words, back into view. As we will discover, in this context, the creative palette of a textually exponential, mixed media post-war Varda becomes newly, fascinatingly, accessible.

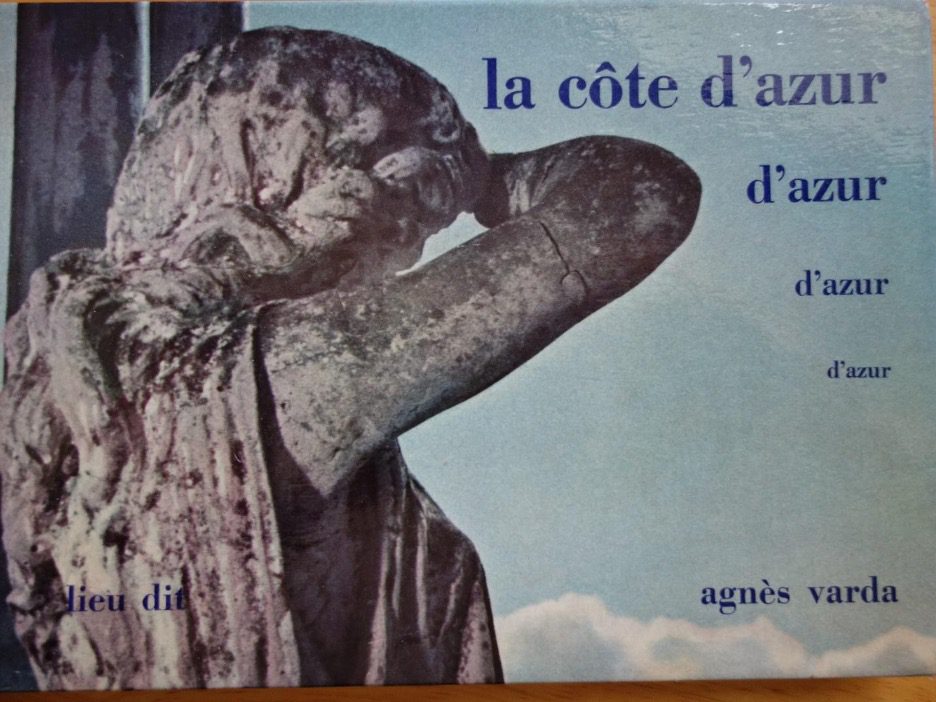

A primary source here is Varda’s La côte d’azur anthology, which is best thought of both as a vision statement, notating the creative methods Varda had devised during the 1950s; and an intertextual ‘cousin-album’ to her commissioned film Du côté de la côte (1961: n.p. [8]; see Fig. 2). In both guises, the book offers a fascinating set of micro-manifestoes, Varda’s work-in-progress reports on her young media career. Even in its title, the book is characteristically of Varda’s repertoire: it is technically called in full, La côte d’azur d’azur d’azur d’azur, the last six words shrinking on the cover in recessional typeface, as if Varda offers its contents in endless vanishing mise-en-abyme, like the famous parallel mirror café shot of her star-subject posed in self-scrutiny, in Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 à 7) (1962). Immediately within its pages, however, Varda elaborates her artistic points of departure. Typically arch or evasive when pressed about her methods—Varda’s alphabet of self-declarations in her later book Varda par Agnès, from ‘A for Anomorphosis’ to ‘Z for Zoubliés, Zabsents et Zombies’ (1994: 10-35) is representative—Varda is unusually candid about her modus operandi. Up front, Varda frames the entire côte project—encompassing the original Office National du Tourisme brief, the ‘medium-feature’ she directed, and the book we are now reading—as roaming fluidly ‘between’ the documentary mode and the reflective essay. Via this interstice, Varda sets out her beliefs about craft and practice: ‘It’s not about showing a region, town after town, like a voyage, but more about asking questions of a landscape, idea after idea, like how we chat [comme on bavarde]; hence “La Côte” is at the same time an actual place and a sociological phenomenon’ (1961: n.p.; [8]). Clearly, we should stop referring to Varda’s nonfiction works, post-war and otherwise, as documentaries; they emerge here as Astruc-Vedrès’ trains of thought, conversational mediations, in touch with, but not defined by, the already multifarious essay film mode. Ideally, Varda seeks to blur the actual boundaries between texts, the La côte commission-film-book becoming a kind of radiating composite, a triangulating web of conveyed experience. As such, Varda’s account comprises ‘a re-edition almanac, with complementary information and new materials for reflection … If the images of the film incite a commentary text, we hope that several extracts of the text revive the images of the film’ (1961: n.p.; [8]).

Fig. 2: Agnès Varda’s ‘cousin-album’ book, writing up her creative findings from the 1950s, La côte d’azur (1961).

Fig. 2: Agnès Varda’s ‘cousin-album’ book, writing up her creative findings from the 1950s, La côte d’azur (1961).

Issuing from Varda’s broader declarations, La côte d’azur provides more focused early professional findings. Some are small-scale epiphanies. One such intuition, unique to this book, is a poem actually written by Varda herself, signed modestly, ‘a.v.’ (1961: n.p. [18]). A miniature artistic affirmation, this La côte d’azur poem in- and of-itself represents a real contribution to Varda scholarship. Varda sets her piece beside four photographs, captioned ‘azure flora,’ of contorted tree branches, three leafy deciduous and one the blown fronds of a fragile young palm tree. The images are all deliberately slightly overexposed, so as to heighten their graphic contrasts, the black pools of diurnal shadows versus the thin greys and arid whites of bleaching sunshine. Newly reproduced (above) with my translation (below), Varda’s poem runs:

Palmier sauvage

tu perds tes palmes.

tu perds ton calme.

Oiseau volage.

tu perds tes plumes.

et du volume

Souffle sauvage

tu perds ton temps

tu perds ton vent

(Wild palm tree

you’re losing your palms

you’re losing your calm

Flighty bird

you’re losing your feathers

and your form

Wild breath

you’re wasting your time

you’re wasting away.)

(1961: n.p. [18])

With this poem, Varda’s response to the Mediterranean landscape clearly signals her enduring fascination with ubiquitous, inexorable entropy. Discovering organic splendour, those dancing subtropical palm trees, Varda records the onset of decay, decomposition, a summer being overrun by autumn. Turning her gaze upwards, catching the kinetic blur of a bird in the azure overhead, Varda conveys merely dissolution, an unravelling, corporeal disintegration. And in the very respiration of the landscape, those eddies of swirling wind, Varda feels and recounts the ticking clock of mortality itself. Velocity; dispersal. Energy; stasis. Here, poignantly captured in minutiae, is that characteristic old Varda head on young shoulders, the surge and dissipation of her diegetic world depicted—emphatically—as two sides of the same canvas. The same instinct runs through Varda’s post-war peers, whether it is Vedrès finding World War I’s noxious roots in the pageantry of Belle Époque Paris, or Bellon, in Colette, interweaving its subject’s unstinting artmaking with her corporeal decline. And this rise-fall equation crystallises Varda’s early work. Take L’Opéra-Mouffe, another post-war entropy piece, whose preface shows a pregnant woman’s body (which may either be Varda’s or that of her regular model, Maria G [Lacoste and Sandrin 2023: 24-31]), shot in stark chiaroscuro close-up, belly twitching with gestation, chest pulsing with breath, skin rife with tactile goosebumps—before a brutal cut takes us to a close-up of a nearby market vendor hacking open a pumpkin with a long, serrated knife. Varda’s everyday Mouffe opera hinges too upon an interior tableau of euphoric young lovers whose bodily bliss is counterpart to Varda’s outdoor studies of the aged, the infirm, the homeless, the vagabond humans that inhabit her Paris milieu, the compromised people that Varda intimately observes, and will continue to observe, for the rest of her career.

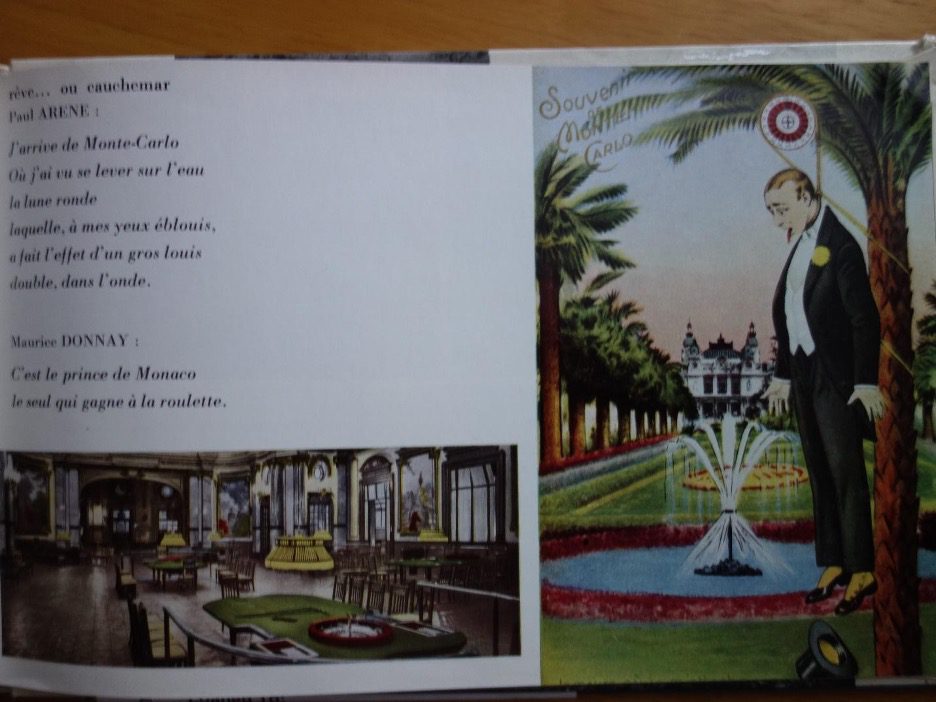

Cued by all this, La côte d’azur’s central parameter, a barometer of Varda’s early media, is her precisely modulated eye for juxtapositions, jagged confluences of layout and content. Recall too Du côté de la côte, Varda’s companion film, for its gallery of regional incongruity: like imported exotic architecture situated in old-fashioned French coastal villages, or ostensibly joyous Nice festivals that mask grisly sexual assaults. Yet, while on-screen Varda’s edits propel us quickly, even subliminally, through these contrasts, on the page Varda’s dissonant montages take on an even more measured impact. La côte d’azur’s actual book format allows Varda to construct two-fold page-spread diptychs, shot/reverse shot pairings that remain, that co-exist. This expressive design makes overt a subtextual instinct of Varda’s work, right from the beginning, revealing the shaping influence of surrealism. For these are deeply disconcerting fusions: angular agave succulents next to desiccated industrial telegraph poles; dour black-and-white Victorian photography beside exuberant Pablo Picasso colour caricatures; the beguiling interior of a Monte Carlo casino affixed to a ‘souvenir’ postcard of a bankrupt aristocrat, tongue lolling, hanging in a roulette-shaped noose from a palm tree (Fig. 3). Characteristically, too, Varda oscillates between past and present, offering next to contemporary shots of incoming tourist hordes obsolete ephemera such as Victorian train timetables, out-of-date Michelin maps, and old car advertisements. The book even allows Varda to perform textual augments impossible in her analogue filmmaking, like daubing colour highlights on top of her coastline photography, as if she herself vandalises the landscape. In—disharmonious—sum, Varda at once prizes cultural history, no matter how obscure the source; while simultaneously, in her gleeful re-arrangements, showing us that textually, for her, nothing is sacred.

Fig. 3: Agnès Varda’s discordant visual montages in La côte d’azur: the caption from Maurice Donnay reads, ‘It’s only the Prince of Monaco who wins at roulette.’

Fig. 3: Agnès Varda’s discordant visual montages in La côte d’azur: the caption from Maurice Donnay reads, ‘It’s only the Prince of Monaco who wins at roulette.’

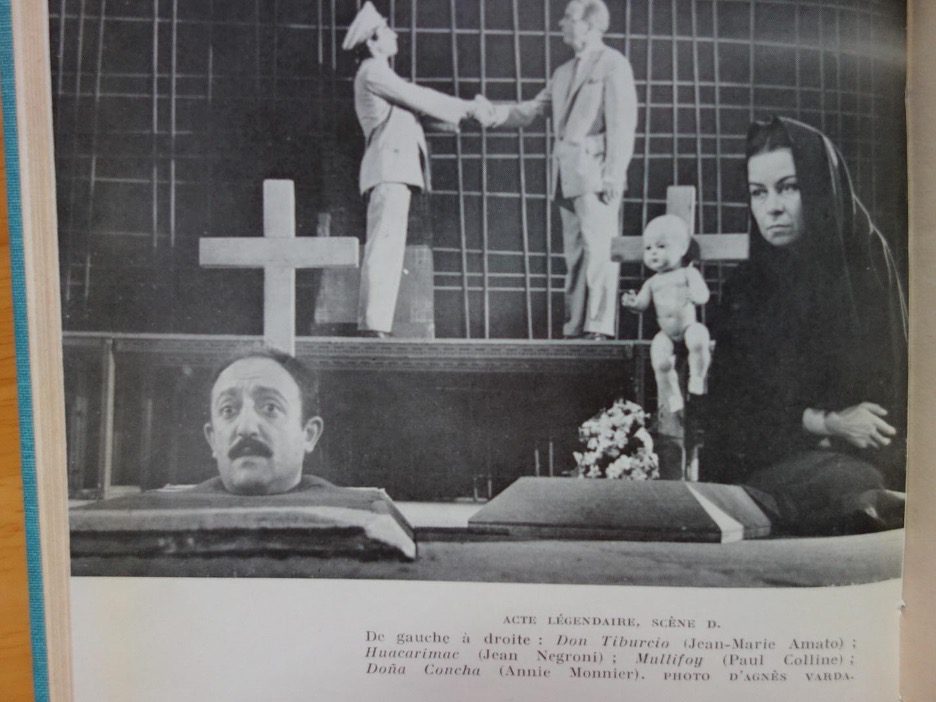

La côte d’azur’s design dichotomies, in fact, underscore Varda’s post-war publications—on the page, on-screen, and even, remarkably, in her single-shot promotional stills. A representative Varda image from the 1959 TNP production of Jean Vilar’s Le Crapaud-buffle (The Cane Toad), published in book form as part of Varda’s regular photographic output during the decade, bursts with these characteristic disharmonies (Gatti 1959; see Fig. 4). This shot’s effects build from, and establish, Varda’s favoured camera setup: framed from a low-height (befitting, but also exaggerating her diminutive stature) vantage point, squinting up in a low angle, flattening depth cues by adopting a longer lens. Here, typically, Varda compresses her photographed mise-en-scène into absurdist shards: for Le Crapaud-buffle a grieving mother, doll baby, and forlorn severed head in aggressive foreground; skewed gridline geometries above a raised dais to the middle; and longer shot figures posed in the too-close rear ground. Varda’s artful grotesqueries recur across her early media; they are vivid, and amplified, throughout La côte d’azur—like the image of the corpse aristocrat hanging outside a well-to-do resort casino, or graffiti carved into lush coastal succulents (including a glimpse of the name Rosalie, Varda’s soon-to-be daughter, hinting at some self-made sabotage of local resources)—becoming a veritable primer of Varda’s highly intentional, albeit disparate approach to style and staging. While clearly Varda’s own idiosyncratic palette, however, these motifs again also channel Varda’s post-war peers. Noël Burch, analysing Franju’s Hôtel des invalides and Blood of the Beasts could just as easily be describing Varda when he reports that these are ‘no longer documentaries in the objective sense, their entire purpose being to set forth thesis and antithesis through the very texture of the film… [they are] meditations, and their subjects are a conflict of ideas… a subtle but fundamental ambiguity underlies the sumptuous imagery’ (1969: 159). The ancestry of Varda’s constructivist editing is clear—Vedrès mentors Resnais mentors Varda—but Varda’s affinity for stark montage (like the opening L’Opéra-Mouffe belly-to-blade collision) and general technical prowess is, it has to be said, a hugely neglected aspect of her work, although it is abundantly clear already within our post-war media sample. Not only do Varda’s stylistic choices contradict the usual gendering of film criticism—in which men enact pragmatic decisions about cuts, camerawork, and style, whereas women exude empathy and feelings—but Varda’s decision-making also reinforces, paradigmatically, her anti-elitist sociological beliefs.

Fig. 4: Representative Varda TNP photography: published still from the 1959 production of Le Crapaud-buffle (The Cane Toad).

Fig. 4: Representative Varda TNP photography: published still from the 1959 production of Le Crapaud-buffle (The Cane Toad).

La côte d’azur reinforces the intentionality of Varda’s stylistic confluences via its overt applied cinephilia. Again, while the on-screen post-war citations in the film Du côté de la côte shift with Varda’s customary editing velocity—to Paris 1900, Colette, Sunday in Peking, as well as À propos de Nice (1930) (Palmer 2022: 84-92)—on Varda’s page these citational ingredients are meant to be appraised in greater detail. Varda herself frames the inquiry: that applied cinephilia is not merely about making playful film history asides but is actually a shaping constituent factor of her cultural analyses. Varda suggests wryly that ‘Cinema, which is one of life’s springboards [tremplins], often uses for its décor this “section of Earthly Paradise”, as Léopold II, king of Belgium, put it’ (1961: [n.p.] 49). Catalogued for this section of La côte d’azur are shots from: Bonjour Tristesse (1958), À propos de Nice, Judex (1916), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), To Catch a Thief (1955), and Foolish Wives (1922) (see Fig. 5). Diverse and non-chronological, what unifies these textual springboards is Varda’s implicit editorial analysis: that her stills graphically highlight glamourous women’s faces—from Jean Seberg to Grace Kelly—filmed so as to appear impish yet unknowable, alluring but disingenuous. These are, in effect, for Varda, female screen stars represented as côte d’azur sirens—that behind the sleek Côte façade, lurking like the predators in the Nice carnival, something more misogynistic festers. Informing Varda’s applied cinephilia, moreover, this part of La côte d’azur clearly revives Vedrès’ approach in Images de cinéma français, which is once again a vital manual for post-war practitioners, unwisely forgotten ever since. Film history à la Vedrès therein becomes a means for feminist gendered analysis: women’s bodies as mise-en-scene motifs, directed initially by men as subordinate attractions on-screen; but then re-presented, re-arranged by an interventionist (female) curator who has a wily, self-reflexive, embedded textual voice. As Varda confirms, concluding on a deeply ironic note, her image-gallery ‘seems more imaginative than cinema itself, reality outstrips fiction’ (1961: [n.p.] 50).

Fig. 5: Sample Varda applied cinephilia in La côte d’azur: femme fatale still from The Lady from Shanghai.

Fig. 5: Sample Varda applied cinephilia in La côte d’azur: femme fatale still from The Lady from Shanghai.

Ultimately, La côte d’azur is best thought of as Varda’s conceptual scrapbook, a multimedia storyboard that beautifully documents her burgeoning craft process. In one particular aspect of Varda’s textual modulations, however, emerges arguably her key affiliation with France’s post-war film ecosystem and all its essayistic forays. This signature device, prized by Vedrès and popularised by her peers, is the interruption-pivot, an especially useful tool for pursuing irony or conceptual humour and avoiding bombast or didacticism—two of Varda’s main artistic enemies. In Paris 1900 this loadbearing swerve, in one defining sequence, has its voice-over narration exclaim, over shots of angry Parisians massing in the street, as if relinquishing editorial control or losing its train of thought entirely, ‘What are these crowds protesting—against whom?’ The climactic stretch of Franju’s Mon chien, similarly, abruptly puts its canine subject, abandoned by its erstwhile family, as the subjective focal point of the film, as if to displace human (screen) agency entirely. And the oscillations of Night and Fog are most notorious in this regard, switching between black-and-white Nazi found footage, and colour rusting train tracks, pondering whether the discrepancy between omniscient present and compromised past might never be reconciled, no matter our intentions. La côte d’azur is built around such about-faces, a driving force of Varda’s methods here, and thereafter. Up front, Varda sets the tone, arguing that her book, despite being rife with historical materials and intertextuality, is not, in fact, an ‘aide-mémoire’ (1961: n.p.; [8]) at all. Instead, its governing instinct is apparently to become an almanac populated with contradictions, its textual identity fragmented. Hence, Varda leaps from hard data (‘Côte d’azur: expression invented by Stéphen Liégeard … title adopted by the Académie Française in 1887… maximum water temperature: 26 degrees, minimum: 11 degrees’) to a ‘half-true half-imaginary museum’ of whimsical paintings and postcards (1961: n.p.; [19; 28]). One section on ‘coastline camps’ has the reader flip the page from lines of deserted luxury beach umbrellas to an apparent shantytown of dilapidated caravans; Varda notes dryly that ‘camp sites are the most aerated forms of freedom’ (1961: n.p.; [38-39]). And, throughout, Varda interjects her trademark recreations of historical artifacts—like a modern red-clad fashion model posed to mirror, and counterpoint, a nineteenth-century poster for the Menton-Paris trainline (1961: n.p.; [13-14). In Varda’s sociological inquiries, everything we witness is ersatz, La côte d’azur reminds us: old is new and new is old; nothing is sacrosanct or reliable. The only concrete throughline, in fact, is Varda herself, ironic cultural engineer, forever offsetting the caustic with the compassionate.

A final, equally overlooked Varda intertext publication distils the main parameter—Varda’s discordant creative entropy—that we have traced throughout our post-war media sample. Literally and figuratively our coda, this case study, an accompanying photographic quadtych, was Varda’s contribution to Anne Philipe’s 1963 memoir, Le Temps d’un soupir (The Time of a Sigh). The book was a meditation on the loss of Anne’s partner, Gérard—who was, of course, Varda’s close friend and colleague from the TNP, as well as star of commercial French cinema, of whom she made publicity glossies throughout the 1950s—after he had declined rapidly, then died from liver cancer in 1959 at the age of just 36. For the first edition hardcover (not reprinted in the 1964 and multiple subsequent paperback editions), Varda created her own, imagistic eulogy to this vanished post-war star (Figs. 6-9). Her four-shot series works on multiple levels: as an intimate long-term summation of Philipe, Varda’s most photographed 1950s subject; an experimental mourning or grief portmanteau; and, physically, folding out in concertina form from Anne Philipe’s actual text, as a miniature image-installation piece that the viewer is able to arrange, edit, and process, in their own hands, much like the act of reading La côte d’azur. Image 1 (Fig. 6) under-develops Varda’s portrait of the reclining couple on stage, abstracting them into an amorphous soft-focus chiaroscuro. Image 2 (Fig. 7) inverts the same shot into negative form, making the duo’s private moment even more graphically abstract, dissolving into a frozen black-on-white tableau. And then the final image couplet (Figs. 8-9) pushes the underdevelopment process even further, turning Gérard and Anne’s bodies into a pattern of dots and lines, curves and shapes in arrangement, with tiny corporeal traces—eyes, mouths, a trace of skin tone, the crook of Anne’s arm—heartbreakingly, vestigially visible. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, pixels to pixels: Varda’s series portfolio is itself like a photographic sigh, a devastating exhalation, as if she tracks her losing battle to preserve the bodies disarranging before her lens, a terminal cancer that attacks the integrity of Varda’s photography. As a composite of Varda’s attachment to Philipe, a distillation of her 1950s photographic career, and a post-war media artist poised in philosophical reflection, this image quartet is some of Varda’s most bravura and representative early work, a stunning expressive tribute to arguably France’s most iconic post-war icon.

Fig. 6: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 1 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir (The time of a Sigh).

Fig. 6: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 1 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir (The time of a Sigh).

Fig. 7: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 2 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Fig. 7: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 2 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Fig. 8: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 3 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Fig. 8: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 3 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Fig. 9: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 4 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Fig. 9: Varda’s photographic quadtych of Gérard and Anne Philipe, 4 of 4, an image pull-out insert in the hardcover first print run of Le Temps d’un soupir.

Conclusion: A New Young Post-War Varda

Re-placing Varda in her actual entry point to French media-making, the teeming post-war cinema ecosystem we have reappraised here, takes us closer to her core values as a practitioner, as well as of the film culture to which she was such a dynamic contributor. Preparatory to Varda’s emergence, and deeply receptive to her approach, our new historiography of post-war French cinema highlights this convergence. Before, during, and after Varda’s arrival we find pivotal craft idioms across mixed media: probing but non-hagiographic social engagements with shared memory, people and their places; commissioned texts that query and frequently challenge their own nominal goals; shorts and medium films that thrive in their subversive and sometimes experimental non-feature format. Unifying this communal media practice is applied cinephilia, the overlap creative conversation that was a vehicle for screen voices just as dynamic, and certainly more diverse, than the notorious New Wave. Within this cohort, Varda, coming in at the end point, so to speak, models certain key expressive parameters; while also formulating signature tactics that would sustain her artmaking for decades to come. Putting Varda’s publications—images, words, pages, shorts—within a continuum, veering away from the traditional bias towards fictional film narratives, we see this professionally surging Varda all the more clearly.

Focusing so intently on Varda’s foundational post-war emergence, moreover her output across expressive formats, also allows us to pinpoint hinge traits of Varda’s creative progress. So acute, so intentional are these mixed media focal points that we can make informed analyses about Varda’s imagistic sensibility, her formative decision-making, the ways she saw, engaged, and represented the world. As we have surveyed, Varda’s post-war work modelled recurrent textual parameters, notably evoking poetic entropy, wry sociocultural associations or paradoxes, and constant veins of essayistic (self-)questioning. Moving closer, we see Varda’s technical affinities: the ironic surrealist juxtapositions, her jarring montage-based aesthetic, even the characteristic camera setups that defamiliarise Varda’s diegetic spaces so artfully. And like her post-war peers, there is a melancholy, even a depressive outlook, to this Varda—a sense of the brittle delicacy of her artmaking actions, that creativity remains subject to its acid confrères: dissolution and destruction, an end to hope. Tasked to deliver a celebration, Varda offers mournfulness, a regretful eulogy for something lost. Prompted to study a buoyant future, Varda turns thoughtfully to after-echoes or disasters from the past. Ultimately, this might make Varda—even in the company of brilliant pioneers like Vedrès, Bellon, and Resnais—one of post-war France’s most representative and insightful practitioners. Varda is certainly a link in that spiritual chain of civilisation that Robert Favre le Bret sought to build through cinema. Either way, though, to understand Varda as a post-war applied cinephile, a book writer-artist-filmmaker, drawing upon, and citing, the media emerging around her, is very much to know her better, to understand her point of origin more expansively, to clearly see those mainstay features of her work that would remain points of elaboration for the long, endlessly creative career to come.

Notes:

[1] All images screen captured by author subject to Fair Use.

[2] Alter and Corrigan correct the wrongheaded notion that Astruc’s post-war essays speak to the New Wave more than a decade away; they do, though, neglect Vedrès, who presented alongside Astruc, frequently in the same journals and at the same public events (Palmer 2021: 125-126).

REFERENCES

Allain, Jérôme (2014), ‘Sur la trace de Nicole Vedrès’, Hypothèses, December 14, https://paris1900.hypotheses.org/category/nicole-vedres (last accessed 15 August 2022).

Alter, Nora & Timothy Corrigan (2017), ‘Introduction’, in Nora Alter & Timothy Corrigan (eds), Essays on the Essay Film, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1-18.

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, New York: Wallflower Press.

Le Bret, Robert Favre (1946), ‘Signification du Festival de Cannes’, in Marc Pascal (ed.), Le Livre d’or du cinéma français, Paris: Agence d’Information Cinégraphique, pp. 17-20.

Burch, Noël (1969), Theory of Film Practice, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Derain, Lucie (1946), ‘Littérature de Cinéma’, in Marc Pascal, Le Livre d’or du cinéma français, Paris: Agence d’Information Cinégraphique, pp. 249-254.

Fiant, Antony & Roxane Hamery (2008), ‘Avant-Propos’, in Antony Fiant & Roxanne Hamery (eds), Le Court Métrage français de 1945 à 1968 (2) Documentaire, fiction: allers-retours, Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp. 7-11.

Fieschi, Jean-André & Claude Ollier (1965), ‘Entretien : Agnès Varda: La grâce laïque’, Cahiers du cinéma, Vol. 165, April, pp. 42-51.

Flitterman-Lewis, Sandy (2022), ‘Passion, Commitment, Compassion: Les Justes au Panthéon by Agnès Varda’, in Kennedy-Karpat & Feride Çiçekoğlu (eds), The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 83-98.

Gatti, Armand (1959), Le Crapaud-buffle, Paris: L’Arche éditeur.

Kennedy-Karpat, Colleen (2022), ‘Sustaining Joy in Varda’s Legacy’, in Kennedy-Karpat & Feride Çiçekoğlu (eds), The Sustainable Legacy of Agnès Varda, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1-14.

Lacoste, Anne & Carole Sandrin (2023), Agnès Varda. Expo 54, Lille: Delpire and Co.

Liandrat-Guigues, Suzanne (2018), Paris 1900 de Nicole Vedrès (1947), Paris: L’Harmattan.

Palmer, Tim (2017), ‘Drift: Paula Delsol Inside and Outside the French New Wave’, Studies in French Cinema, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 144-164.

Palmer, Tim, (2021), ‘Remembrance of Things to Come: Nicole Vedrès, Paris 1900, and the Post-war French Essay Film’, French Screen Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 123-145.

Palmer, Tim, (2022), ‘Beside Du côté de la côte: Agnès Varda’s Early Applied Cinephilia’, Short Film Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 81-95.

Philipe, Anne (1963), Le Temps d’un soupir, Paris: René Julliard.

Russell, Catherine (2018), Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Standish, Isolde (2011), Politics, Porn and Protest: Japanese Avant-Garde Cinema in the 1960s and 1970s, New York: Continuum.

Truffaut, François (1954), ‘Une certaine tendance du cinéma français’, Cahiers du cinéma, Vol. 31, pp. 15-29.

Varda, Agnès (1961), La côte d’azur, d’azur, d’azur, d’azur, Paris: Éditions du temps.

Varda, Agnès (1962), Cléo de 5 à 7, Paris: Gallimard.

Varda, Agnès (1994), Varda par Agnès, Paris: Cahiers du cinéma.

Vedrès, Nicole (1945), Images du Cinéma Français, Paris: Les Editions du Chêne.

Vedrès, Nicole (1948), ‘A la poursuite de Paris 1900’, L’Écran français, March 2, pp. 3-4.

Wheatley, Catherine (2023), ‘Alice Diop in Conversation with Claire Denis’, Sight and Sound, Vol. 33, No. 2, March, pp. 34-42.

Films

À propos de Nice (1930), dir. Jean Vigo.

Afrique 50 (1950), dir. René Vautier.

Afrique sur Seine (1955), dirs. Mamadou Sarr & Paulin Vieyra.

Avec André Gide (1951), dir. Marc Allégret.

Bonjour Tristesse (1958), dir. Otto Preminger.

Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) (1962), dir. Agnès Varda.

Colette (1950), dir. Yannick Bellon.

Dimanche à Pékin (Sunday in Peking) (1956), dir. Chris Marker.

Django Reinhardt (1957), dir. Paul Paviot.

Du côté de la côte (Along the Coast) (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

Foolish Wives (1922), dir. Erich von Stroheim.

Goëmons (1947), dir. Yannick Bellon.

Guernica (1951), dirs. Robert Hossens & Alain Resnais.

Hôtel des Invalides (1952), dir. Georges Franju.

Judex (1916), dir. Louis Feuillade.

L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

La Première nuit (1958), dir. Georges Franju.

Le Sang des bêtes (The Blood of the Beasts) (1948), dir. Georges Franju.

Le Théâtre national populaire (1956), dir. Georges Franju.

Les Statues meurent aussi (Statues also Die) (1953), dirs. Alain Resnais, Chris Marker & Ghislain Cloquet.

Lettre de Sibérie (Letters from Siberia) (1958), dir. Chris Marker.

Mon chien (1955), dir. Georges Franju.

Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog) (1955), dir. Alain Resnais.

Ô saisons, ô châteaux (1958), dir. Agnès Varda.

Paris 1900 (1947), dir. Nicole Vedrès.

The Lady from Shanghai (1947), dir. Orson Welles.

To Catch a Thief (1955), dir. Alfred Hitchcock.

Toute la mémoire du monde (All the World’s Memory) (1956), dir. Alain Resnais.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey