Agnès Varda: In-between Medium, In-between Animal

by: Sam Kaufman , November 7, 2023

by: Sam Kaufman , November 7, 2023

‘In what sense can an artist be true to her materials, or have medium specificity, when the entity being incorporated is completely misunderstood?’ Arnaud Gerspacher (2002: 5)

*

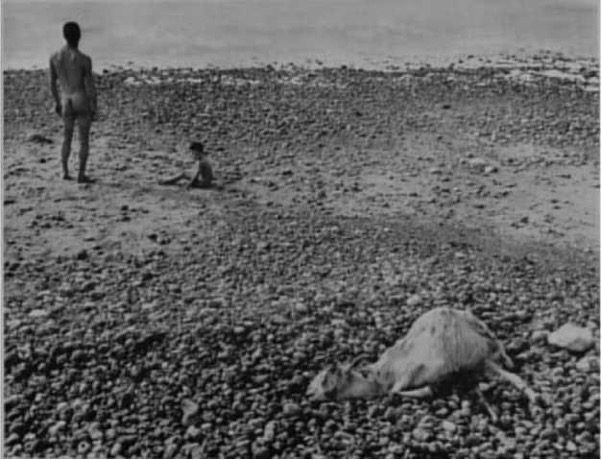

In her short film Ulysse (1982), Agnès Varda considers a photograph she took almost 20 years earlier in 1954 of a naked man, a boy, and a dead goat on a beach in Calais (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Ulysse (1982)

Fig. 1: Ulysse (1982)

Varda interviews the image’s subjects and asks about their memories of the day it was taken. Fouli Elia, the man in the image, cannot remember the day in any real detail. When Varda attempts to jog his memory further by interviewing him in the nude, showing him a print of the photo, and giving him some pebbles from the beach, he can only really recall the embarrassment of his nakedness. The boy, Ulysse Llorca, interviewed in the bookshop he now runs, cannot remember a single detail of the day, even when presented with the photograph. He concludes, ‘everyone has his own story. No matter how troubling the gap between the real and imaginary may be.’ [1] Finally, pondering in voiceover on how to interview the goat, Varda shows a print of the photograph to what she calls ‘just a goat, any goat’ and asks, ‘How does she see her own goat image?’ The goat responds by eating the photograph. Varda continues, ‘Without making animals talk, like in American cartoons, or defining memory as a rumination of mental images, may I suggest that there is un imanginaire animal, a self-predatory imagination?’ [2]

After this scene, Varda seems concerned by her subjects’ lack of recollection and the possible conclusion that the photograph has no actual relation to any memory of lived experience on that day. She attempts to contextualise the memory she cannot find by thinking about the subjects’ familial histories and the collective memory of major historical events of the summer of 1954, as well as how she would go on to shoot La Pointe Courte (1955), her first feature film, a few months later. This exercise relies on an interplay of Varda’s two main media—film and photography—which does not, ultimately, resolve into the clear mode of memorialisation she appears to be seeking. Indeed, the indeterminacy of human and nonhuman memory at the core of the film defines the larger problematic concerning medium and memory that is the subject of this essay. On a simple level, Varda is asking how memory is contained or constructed by the media of its representation and those media’ particular attachments to the moments they capture. On another level, she is exploring how moving beyond received notions of medium specificity can open spaces for more complex expressions in the interplay of film and photography. [3]

This essay will consider Varda’s formulations of memory through medium by following recurring appearances of this photograph, from Ulysse to Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2008) and, to a lesser extent, Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017). I will sketch out an argument about intersections between memory and medium that trouble the boundaries between cinema, photography, and memory, as well as the particular historical values ascribed to medium through indexicality. I will apply Jacques Rancière’s concept of the ‘sensorium’ to question the boundaries of media and argue that Varda’s work on memory reaches beyond the confines of medium specificity. In the final part of the paper, I will make a more speculative connection between the concept of the sensorium and the biosemiotic model of the Umwelt to make the case that Varda, more radically and especially in the case of Ulysse, imagines—imangines—a space for memory beyond the confines of medium- and, indeed, species-specificity.

Varda’s early career as a photographer for the Théâtre National Populaire and her later use of the still image in her film work as a way of interrogating collective and individual memory is well-documented. [4] She has herself written about her perspectives on the boundaries between the two media: ‘Photography never ceases to instruct me when making films. And cinema reminds me at every instant that it films motion for nothing, since every image becomes a memory, and all memories congeal and set’ (Campany 2007: 62). She sees a strain between the two: ‘Cinema and photography throw back to each other—vainly—their specific effects … To my mind cinema and photography are like a brother and sister who are enemies … after incest’ (Campany 2007: 63). Her logic that cinema ‘films motion for nothing’ because its individual images ‘congeal and set’ is an acknowledgement of cinema’s constituent basis in photography—the photograph is the material reification of cinema’s ghostly motions, and the process of congealing describes photography’s potential indexical relationship, either to a profilmic event or, as in the case of this essay, memory. This first-principal understanding of cinema is echoed by Laura Mulvey’s study of the semiotics of the gap between stillness and movement in Death 24x a Second. One of Mulvey’s main points of reference is a sequence from Man with a Movie Camera (1929) in which Dziga Vertov freezes the film’s frantic movement and reveals individual still frames on reels of processed celluloid while being edited. For Mulvey, the still images here ‘represent the individual moments of registration, the underpinning of film’s indexicality,’ in essence, recalling an original collection of instants in their capture (2006: 15). As she puts it, ‘The still photograph represents an unattached instant, unequivocally grounded in its indexical relation to the moment of registration. The moving image, on the contrary, cannot escape from duration’ (2006: 14-15). This ‘blending of two kinds of time’ (2006: 16) works in Ulysse and Les plages as an exploration of the representational apparatus through which memory is carried and how time consequently works through the tension between the image in motion and in stillness.

Mulvey’s use of the index, following Peircean semiotics, is distinct both from the icon, which denotes a resemblance to the signified, and from the symbol, which conveys a conventional or arbitrary relationship (Doane 2007: 1-2). The index is a causative signifier with direct physical evidence of its objects (Doane 2007: 2). Indexicality has long been central to the traditions of photography and film criticism, not least due to the work of André Bazin [5], but despite the familiarity of this material, it is still worth addressing here in order to establish exactly what Varda is working to move beyond. Russell Kilbourn argues that the historical conception of photography and film, based on Peirce’s distinctions between signs, follows along these lines: ‘Whereas the (analog) photograph is always a representation of something past, over and done, film, in its iconicity, is “life”; photography, in its indexicality, is “death”’ (2012: 29, emphasis original). Kilbourn distinguishes film from photography through the icon (resemblance) and the index (physical and causal connections) respectively. More so than Mulvey, he strictly demarcates the boundaries between film and photography based on their distinct semiotic categories and insists on a medium specificity somewhat locked in its own limitations. Yet in Varda’s work, it is the potentiality of the index, rather than its definite existence, that is important, and her exploration of that potentiality via the indexicality of memory troubles any certainty that the material stillness of the photographic image has any ties at all to a memory of what it represents. Rather, memory is itself an index that mediates the uncertain space of cinema and photography’s endless throwback.

Ulysse thus troubles the clear semiotic distinction laid out by Kilbourne via an exploration of what memories or events are actually linked indexically to the photographic image. Ari Blatt argues that Ulysse ‘aims to breach that gap’ between individual and collective memory ‘to evoke ways in which her photograph might align itself with a certain experience of history, of history with its capital “H”’ (2011: 186). So, the process of remembering through Ulysse in 1982 is an attempt to re-establish what Varda in 1954 thought her still image could achieve, and this re-establishment brings with it a particular Historical weight, recalling not the individual memory of the moment of registration, but France’s wider national memory. Blatt is not convinced that Varda succeeds: ‘Even though the film recognizes in the photograph a curious mix of the real and the imaginary, of its link to history, the past, and personal memories of various kinds, the image, in the end, is what we make of it’ (2011: 187). Alison Smith, similarly, thinks that ‘Varda seems to have established that a photograph alone does not in fact hold a concrete, objective memory; as a key to the past it can only function in conjunction with the consciousness of the people involved’ (1998: 155). Indeed, she does not find what she is looking for in the photograph, despite her employment of the capacities of cinema to gain the access to a collective memory the photo evidently did not have. Her photograph, it would seem, has a far more slippery, less direct relationship to the past than the category of indexicality might indicate.

In Les plages d’Agnès, Varda similarly constructs different layers of representation, although at a much greater quantity and complexity than in Ulysse and continues to tease out the entanglements between still and moving images in their role as vehicles for autobiography. There is a direct, albeit brief, return to Ulysse. She remembers and re-enacts her years as a teenager in Sète, the fishing town in La Pointe Courte, gathering and gleaning artefacts and debris from her past to reconstruct physical structures and situations. She remembers the men she knew and says in voiceover, ‘Any man who gazes at the sea is a Ulysses who doesn’t always want to go home. All the children I love, and all the men who gaze at the sea, I call them Ulysses.’ As she says these lines, the photograph from Ulysse appears onscreen, yet now the goat is cropped out and instead of the familiar black-and-white sea, there is a moving, digital, vibrantly blue sea superimposed over the original picture (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Les plages d’Agnès (2008)

Fig. 2: Les plages d’Agnès (2008)

Recalling Mulvey’s ‘blending of two kinds of time,’ Varda returns to a past image and explicitly alters it with the present. In 2008, the question she asked of the photograph in 1982 no longer seems to have as strong a hold. It no longer matters that the medium of the still photograph does not contain an inherent attachment to the moment it was taken. Neither (for the time being) does it seem to matter that she has removed the goat, the object of the boy’s gaze in the ‘original’ and, as she explained in Ulysse, the reason she chose the framing of the photograph, where, indeed, the goat is arguably the punctum, Barthes’ term designating a ‘“detail” which fills the whole picture’ (1981: 45). There is no dialectical process within the relationship between the still and the moving image; rather, the two media blend within Varda’s own practice of memorialisation and her fictionalisation of the name Ulysse. Here, in 2008, the child’s name takes on a fictional, masculinised universality. Moments after this shot, she recreates the scene of the photograph in a profoundly reduced form, this time wholly within the space of Les plages, with only the man visible and herself present within it as the agency of its changing form (Fig. 3):

Fig. 3: Les plages d’Agnès (2008)

Fig. 3: Les plages d’Agnès (2008)

Like the superimposed image, this shot is brief and seems to happen at the tail-end of a re-enactment. All we see is Varda rushing over with a blanket to cover the nude man. The scene is constructed entirely in its staging, framed not by the medium which registers it, but by its happening within a collage of memory. Thus, Varda removes the original photograph’s distinct status and embraces an anti-indexical position, outside of the time of capture, and within an indistinct and fluid collection of representations. This process works through a constant movement of return, of combing again and again through a particular image across decades, unearthing layers of often contradictory signification and contradictory subjectivities. By removing the goat in these re-enactments in Les plages, the images take on a slightly uncomfortable archaic, masculine Romanticism which Varda promptly rushes to cover up with a blanket. It is as if this steady reduction of the original photograph, via other photographs, other formats, other media, from man, and goat, and boy to man and boy to simply man in the final incarnation reaches a point of overly distilled, dissatisfying failure for Varda who now needs to rush in both to conceal the body and the scene, and to display herself doing so. [6]

It is here that I turn to Jacques Rancière, who has argued that ‘the multiplication of apparatuses contributes … to creating zones of neutralization wherein technologies are undifferentiated and exchange their effects, where their products present a multiplicity of gazes and readings’ (2011: 42). In Rancière’s logic, Varda’s multiplicity of media and formats representing a plurality of histories and memories ultimately does not demarcate boundaries between them. It is, crucially, de-specified in what he calls ‘mediality’ (2011: 36). Mediality is the result of ‘the relation between three things: an idea of medium, an idea of art and an idea of the sensorium within which this technological apparatus carries out the performances of art’ (2011: 36). The scattered, layered memories at play in Les plages form a sensorium in this sense, in which the still image is less in a strained reciprocity with the moving image but reaches beyond the bounds of medium towards the more complex historical environment of apparatus. In Les plages Varda does not solve the problem of the index raised in Ulysse: she thinks beyond it. If, as in Rancière’s model, her confrontation of photography and cinema is not a query of their individual or opposing specific functions, there is no longer a problem to solve.

The idea of the sensorium opens up ways of thinking about how Varda establishes complex representations of memory within a post-medium environment. Environment and space are key to this conceptualisation, and Varda migrates her works between spaces as a way of gathering and incorporating different disciplinary methods. Jenny Chamarette has commented on Varda’s installation work, specifically Les veuves de Noirmoutier (The Widows of Noirmoutier) (2005) which Varda also shows in Les plages. Chamarette uses Giorgio Agamben’s writing on gesture to argue that the relocation of Varda’s work ‘transmits across media and modalities’ (2013: 55). As well as gesture, the migration of the work across space also requires a migration of apparatus and of the apparatus’s function. As Chamarette also points out, art history and film studies ‘are struggling to take account both of the cultural, historical and spatial specificity of moving-image installation, and its inevitable bonds with experimental film, cinema, video art and other forms of contemporary lens-based and site-specific artworks’ (2013: 49). This struggle speaks to a potential continuing theoretical adherence to medium-, apparatus-, and even discipline-specificity. Of course, the idea of the post-medium is not without its strong counterarguments. Rosalind Krauss has offered some of the toughest words against a Rancièrian mediality, calling it a ‘monstrous myth’ (2010: xiv) and appeals for criticism which can ‘reclaim the specific from the deadening embrace of the general’ (1999 [2]: 305). Francesco Casetti similarly maintains a medium-specific position while still celebrating film’s ability to exceed its own capacities: ‘The new medium does not represent a betrayal, but rather an opportunity: it gives the media the chance to survive elsewhere’ (2012). The history of expanded cinema too, does not necessarily break with a medium-specific attitude in order to expand film beyond its boundaries in a cinema. [7] Yet, what distinguishes Varda’s practice is the fact that the particular formal strategies she uses to explore her own memory necessarily require zones and aesthetics beyond the specificities of any particular medium or practice. Her constant revisions of old work are processes of remembering and revising attempts at finding, or failing to find, the specific in a medium. As such, the revision of the photograph from Ulysse in Les plages is a realisation of the complexities of both medium and memory, and a creation of a new aesthetic zone in which both exceed their bounds. Memory is not repetition, but a temporal unfurling, via revisitation, into a future. Varda’s impulse to revise is a willingness to question the past and to establish an environment in which memory drives her work beyond the specificities of its own historical times and places. This is not, so to speak, a theoretical commitment: she is not killing off cinema or advocating a universal post-medium condition, and her rejection of photography’s indexicality is a rejection of only one aspect of its formal properties as a medium. She is simply utilising non-medium-specific techniques for her own memorial purposes. By denying the index its supposed essentialism within photography as a medium, she denies its authority as a medium over the actuality of her memory and the formal potential of that actuality for her work as a filmmaker.

Un Imanginaire Animal

Having established the complex potentialities of Varda’s medium-fluidity, and in a gesture at Varda’s own method of revisiting images, I want now to look again at the goat from Ulysse. If Varda’s medium-fluidity functions as a flattening out of the authority of medium and index over memory, how far does Varda extend its radical potential for making space for wider memory, semiosis, and subjectivity beyond the human?

In the photograph, the diagonal arrangement situates three distinct subjectivities within the frame, each emanating very different functions upon that frame: Fouli Elia performing his Romantic masculinised gaze out to the unseen expanse of the sea, inattentive to the scene behind him; Ulysse Llorca breaking the composition by directing his attention, perhaps somewhat distractedly, towards the striking dead body of the goat; the goat itself, a dead presence marked against the live humans, yet punctuating the image, indeed almost overwhelming it. As outlined earlier, when Varda attempts to interview a stand-in ancestral goat (‘just a goat, any goat’) about her memories of the day, she eats the photograph and Varda wonders about a ‘self-predatory imagination,’ ‘un imanginaire animal.’ Here the goat is operating in a totally different mode to the visual memory Varda tries to stimulate in the two human subjects. She, the goat, does not submit to the visual procedures of photography, and instead literally consumes and destroys the print. She also refutes Varda’s attempts to impose a filmic strategy to interrogate the elusive indexicality of the memory. It is not a failure of representation that the goat initiates, but an irruption of the larger representational mode to which Varda subjects her. The goat does not become reduced to metaphor or allegory, does not become a stand-in for a mythic presence, nor does she primarily become a proxy for the feminine in the photograph; she is ‘just a goat, any goat.’ Not only is Ulysse demonstrating the falsity of any one medium’s privileged access to memory, but also demonstrating, albeit partially, how nonhuman subjectivity underlines and injects the necessity of alternative, complex notions of what medium-fluidity can do. Image becomes imange, a goatly medium operating beyond optics. Imanginaire is a mysterious refusal, beyond the human sensorium and its ability to create and solidify memory.

Rancière’s sensorium, an environment in which diverse representational modes and semiotic weights interact and give each other charge, has a related, biological-aesthetic concept–the Umwelt. Without elaborating too much on the complicated web of Umwelt theory developed by the biologist Jakob von Uexküll and its long history of theoretical adaptations, it is worth bringing up as a way of thinking about the overlap between aesthetics and biology beyond the human. In essence, Uexküll frames the Umwelt–or the environment–as a world among many, accessible and charged with meaning by the life within it. That is to say, a world or a milieu does not impose its conditions like spatio-temporal constants upon a creature which can only react reflexively–rather, each creature determines the significance of its relationship with these conditions according to its biology (2010 [1934]: 52). For Merleau-Ponty, building on Uexküll in his lectures at the Collège de France, the concept of the Umwelt opens up the category of animality, or what he calls ‘incorporated meaning’ (2003: 166). Varda’s goat’s Umwelt contains its imanginaire, its relationship with its aesthetic world mediated on a sensitive plane altogether different from a habituated human one. The goat literally consumes the photograph, metabolising its meaning through its body.

The introduction of the goat’s Umwelt as part of Varda’s pondering on the relationship between photography and memory is an incursion into anthropocentric trajectories of signification. Indeed, the goat of Ulysse is not the only prominent appearance of a goat in Varda’s oeuvre, even if she does carry the most disruptive force. In Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), Mona’s itinerancy is momentarily interrupted on a philosophy graduate’s goat farm, and she has a brief respite from the abuse she suffers outside of it. A shot from her arrival on the farm echoes the generational arrangement of the photograph in Ulysse and rearranges gender and the directions of attention between the human and nonhuman subjects (Fig. 4). The goats mediate and somehow filter the otherwise direct moment of empathy between Mona and the goat farmer’s daughter:

Fig. 4: Sans toit ni loi (1985)

Fig. 4: Sans toit ni loi (1985)

In Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017), JR and Varda encounter two goat farms, one of which enforces docility by removing their goats’ horns, and the other of which lets the goats keep them and stands as a quiet opposition to the mutilation facilitating large-scale animal agriculture in France. Again, in both instances, goats are more than symbolic, and Varda lets them exert their full creatureliness not necessarily on how the films arrange their different media (as is the case in Ulysse) but rather on how their narrative and politics operate in the domain of the animal. It is after this sequence of Visages Villages, once JR pastes a large mural of a goat with its horns on a farm building, that the photograph from Ulysse once again appears. Varda hopes to paste it onto a World War 2-era bunker which, in an eerie echo of the fate of the goat’s body, had fallen from a cliff-top onto the very same beach in the 90s. JR, somewhat dismissively, discounts this image for the project and opts for another. In any case, through these sequences, we see a care that goes beyond the human–a care not only for the welfare of the goats that Varda and JR encounter, but care expressed by allowing them to exist and exert themselves upon Varda’s creative process into generously uncertain and inscrutable modes.

Varda’s work does not contain and dominate her goats as negatively Other, but constantly attempts, across several decades, to develop new kinds of reciprocity with them through difference. She realises what Laura Marks calls ‘empathic non-understanding’ (2002: 39) with the goats she encounters and re-encounters. Not only does Varda’s work glean and gather a multiplicity of apparatuses, but also a multiplicity of Umwelten wherein subjectivities beyond the human perform their irruptions, incursions, and creaturely poetics on and through the significance of those media. Her work constantly reintroduces generative uncertainties, folding, and unfurling images in different directions and ensuring that medium, subjectivity and signification always become fluid, gathered, blended, otherwise and multiple, and that memory exists in a space ungrounded from a closed-off ontology of specifics.

Notes:

[1] English quotations are taken from the subtitles to the Criterion Collection edition of Ulysse.

[2] ‘Un imanginaire animal,’ a pun on ‘imaginaire’ (imaginary) and ‘manger’ (to eat), is Varda’s French, bizarrely translated by Criterion as ‘eatingmagination.’

[3] I follow Rosalind Krauss’s distinction between media (‘technologies of communication’) and media (the plural form of a physical representative apparatus) (1999 [1]: 57 n.4).

[4] See Smith (1998), Blatt (2011), and Les plages d’Agnès itself for details on Varda’s specific relationship in-between these media. See Campany (2007) for the broader context of the relationship between still photography and cinema.

[5] See for instance Bazin, ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’ in What is Cinema?, Vol.1 (1967: 9-16).

[6] The man’s nudity against Varda’s utter clothedness, as well as her rush to cover him up, is a striking image in itself, and there is more to be said elsewhere about this distinction of surface, skin, and gender in Varda’s approach to feminist aesthetics.

[7] For expanded cinema see Youngblood (1970), Curtis et al. (2011), and Marchessault and Lord (2007).

REFERENCES

Atkin, Albert (2005), ‘Peirce on the Index and Indexical Reference’, Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society: A Quarterly Journal in American Philosophy, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 161-188.

Barthes, Roland & Richard Howard (1981), Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill and Wang.

Bazin, André and Hugh Gray (1967), What is Cinema?, Vol.1, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Blatt, Ari J. (2011), ‘Thinking Photography in Film, or The Suspended Cinema of Agnès Varda & Jean Eustache’, French Forum, Vol. 36, No. 2/3, pp. 181-200.

Campany, David (ed) (2007), The Cinematic, London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Casetti, Francesco (2012), ‘The Relocation of Cinema’, Necsus, Autumn 2012, https://necsus- ejms.org/the-relocation-of-cinema/#top (last accessed 24 Jan 2023).

Chamarette, Jenny (2013), ‘Between Women: Gesture, Intermediary and Intersubjectivity in the

Installations of Agnès Varda and Chantal Akerman’, Studies in European Cinema, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 45-57.

Conway, Kelley (2014), ‘Responding to Globalization: The Evolution of Agnès Varda’, SubStance, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 109-122.

Curtis, David, Al Rees, Duncan White & Steven Ball (eds) (2011), Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film, London: Tate Gallery.

Doane, Mary Ann (2007), ‘Indexicality: Trace and Sign: Introduction’, differences, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1-6.

Gerspacher, Arnaud (2022), The Owls Are Not What They Seem: Artist as Ethologist, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Jeong, Seung-hoon (2011), ‘The Para-Indexicality of the Cinematic Image’, Ontologia del cinema, Vol. 46, pp. 75-101.

Kilbourn, Russell (2012), Cinema, Memory, Modernity: the Representation of Memory from the Art Film to Transnational Cinema, Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Krauss, Rosalind (1999 [1]), Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, London: Thames and Hudson.

Krauss, Rosalind (2010), Perpetual Inventory, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Krauss, Rosalind (1999 [2]), ‘Reinventing the Medium’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 289-305.

Marchessault, Janine & Susan Lord (2007), Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Marks, Laura U. (2002), Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice & Robert Vallier (2003 [1952-1960]), Nature: Course Notes from the Collège de France, Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Mulvey, Laura (2006), Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image, London: Reaktion.

Rancière, Jacques, Andrew McNamara & Toni Ross (2007), ‘On Medium Specificity and Discipline Crossovers in Modern Art’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 98-107.

Rancière, Jacques (2011), ‘What Medium Can Mean’, Parrhesia, Vol. 11, pp 35-43.

Smith, Alison (1998), Agnès Varda, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Uexküll, Jakob von and Joseph D. O’Neil (2010 [1934]), A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: with a Theory of Meaning, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ward, John (1968), Alain Resnais, or the Theme of Time, London: Secker and Warburg.

Youngblood, Gene (1970), Expanded Cinema, London: Studio Vista.

Films

Jacquot de Nantes (1991), dir. Agnès Varda.

La Pointe Courte (1954), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I) (2000), dir. Agnès Varda.

Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès) (2007), dir. Agnès Varda.

Man with a Movie Camera (1929), dir. Dziga Vertov.

Sans toi ni loi (Vagabond) (1985), dir. Agnès Varda.

Ulysse (1982), dir. Agnès Varda.

Visages Villages (Faces, Places) (2017), dir. Agnès Varda.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey