‘It’s like magic’: A Conversation with Finnish Comic Artist Jiipu Uusitalo

by: Luca Tainio & Wibke Straube , March 30, 2023

by: Luca Tainio & Wibke Straube , March 30, 2023

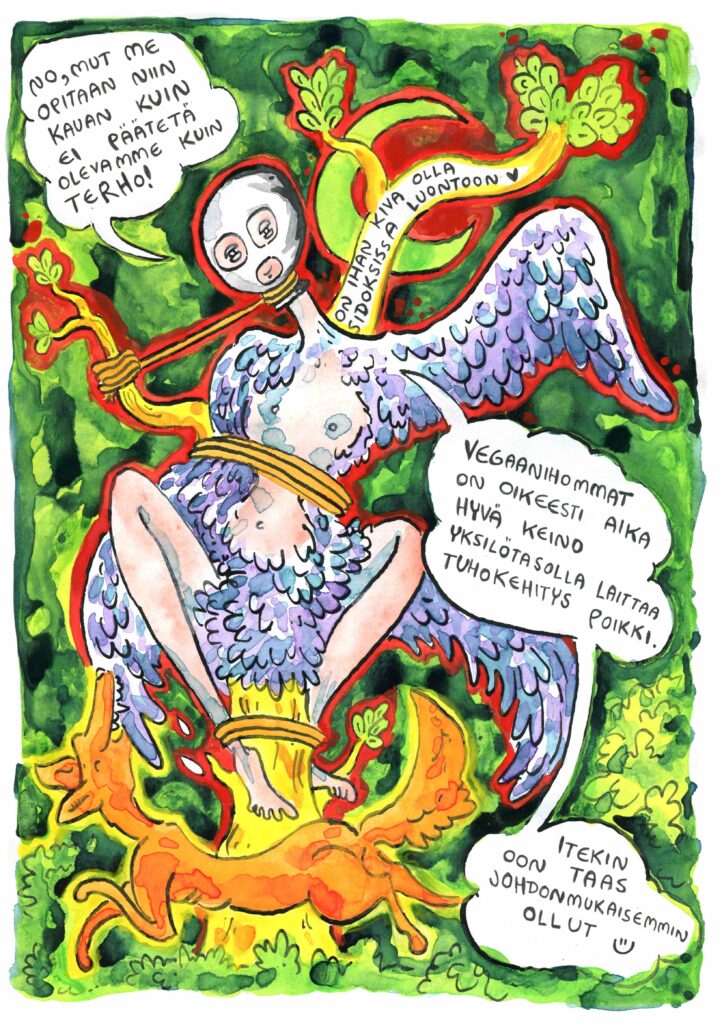

Jiipu Uusitalo publishes transfeminist comic art in their blog Tajukankaankutoja. Their work has been included in different anthologies, and they also recently published a comic trilogy of their own work. Jiipu’s blog was awarded the Comic Blog of the Year in 2017, and Jiipu was just chosen as the festival artist of the renown Helsinki Comics Festival 2022. In their humble way this makes them one of the most read artists in Finland. Considering this, Finland is not only the country of a million lakes and very few people but also quite a high number of wonderful trans and queer feminist comic artists. Jiipu is here in the company of people like H-P Lehkonen, Kimmo Lust, Niko-Petteri Niva, Pii Anttonen, Jenna Oldén and Wolf Kankare. We are excited and grateful Jiipu was able to meet us for a conversation, as their art touches us both in different ways. We have both known Jiipu for many years, indeed Luca and Jiipu are long-term political collaborators. As friends, they have for years been part of the same queerfeminist/activist/anarchist communities in Finland and have been community organisers in Tampere. Wibke came to know Jiipu and their art through Luca, and Jiipu’s aesthetics sparked their interest as they are curious about transecological imaginaries and utopian worldmaking in art. So, in many ways, Jiipu’s work fascinates both of us in the way their images craft fully shape new worlds, tilt normality upside down, and destabilise constricting norms of gender with a good twist of posthumanism and some magic.

***

Wibke & Luca: Luca and I were just talking about feminism and feminist comics, and thinking about what’s happening right now, sort of in the visibility of what is in the scene available in terms of comics relating to transfeminism and queer feminism. There has been a lot of queer and trans comics coming up in the last maybe five to ten years. There is a really big change happening, and your work contributes to this profoundly. We were wondering if you would maybe like to first tell us more about the trilogy you recently published. Maybe by summarising when it came out, and what it is about?

W: Would you tell us more about how you came up with these three different themes of the books?

Jiipu: Punitive power somehow felt like such a fundamental form of power. It is such a brutal form of power, that if you don´t act according to another’s will or norms, you will be punished. It’s a simple—or at least seemingly simple—pattern of power. So that was, in a way, an easy starting point. I was also terribly interested in economy; also because I knew so little about it. And that was the book where I somehow learned the most. I hadn’t even understood what money was. But when I read about it, then I was like, okay, wow, so it´s this kind of a system… I hadn’t understood this at all. Then the last part on social power is something that has been talked about the most. But there was of course also an element of randomness, and some forms of power were left out.

W: Say a bit more, please, on this book on social power. This seems really interesting.

J: Yes, I was wondering if this could have been called something like identity-based power, but then again not all of the aspects discussed in the album necessarily connect to how the ones in power or the subjects of power—the ones struggling in the web of power—actually self-identify. Disability, for example, can be a label given to a person from the outside, but not necessarily how one would identify themselves. Class background as well can be this unnamed, even unconscious, factor that defines one’s position in different power structures. So, in short, the album is about these conceptual boxes that regulate power relationships pretty much regardless of people’s identities—this is what I call social power.

W: The aesthetics of your comics, the stories and the characters you develop, are clearly embedded in radical leftist, queer transfeminist politics. They also allow a different type of agency to non-human animals. Would you tell us more about how you see the connection between feminism and trans politics and how this relates to what bodies and creatures you choose to show in your work?

J: Because the only believable form of feminism—TERF ‘feminism’ I consider as merely a bashing tool for conservatives—has to also include a trans point of view. The function of art is to guide the way to utopias, and I think one of those utopias could be one where we better acknowledge that we are also, in a very concrete sense, free, ever-changing symbiotics; our bodies include bacteria as much as our ‘own’ cells; a sort of a posthumanist viewpoint.

L: So, this is why you prefer drawing characters that are both human and animal, or make reference to monstrosity, as in the trilogy’s character Liina? Would you tell us more about your thinking behind this?

J: Well, in that trilogy, perhaps the key is the dog … that also speaks and participates in family life. That dog is a lot of that … and I like to push those boundaries. And that dog, among other things, inexplicably changes sex, so the characteristics of its physical sex transform during the trilogy. And it’s the kind of limitless character with whom I consciously intended not to care what its animalness meant. It’s a limitless character that has faded the boundaries between human, animal, and gender.

L: And the dog also looks a bit like Nana? (Jiipu’s partner’s dog)

J: That’s true, she has influenced it. I mean there is a link to Nana, with the body language and movement and all, she has influenced the character a lot.

L: And also maybe in a wider sense, how much do you kind of create a background for the characters in the sense of, for example, gender and sexuality?

J: The three main characters. The main idea is that they’re in a polyamorous relationship. [The] Finnish language is great in that you don´t have to gender anyone with pronouns, for example, so you can leave it unmentioned. From writing´s perspective I have always thought that Kolja and Martta are trans because that influences my writing, how I write about them. Liina, I haven´t considered as trans but that is never mentioned anywhere. But for me it´s easier to write thinking that two are trans and one is not.

L: Was that a conscious decision?

J: Yeah. I don’t want to … for me it’s also kind of fun to wonder if readers pick up on—if a trans reader picks up on—that, or if [a] non-trans reader understands what is meant. It’s fun, how different people read that. But I have avoided explicitly mentioning gender. So the relationship form is the only thing that is mentioned there.

W: Nature seems to play a super important role in your aesthetics. There are forests, animals, bears, trees, plants… What does nature mean to you? And does it have anything to do with feminism or gender norms, in your opinion?

J: For me, feminism, anarchism, and other forms of deconstructing power relationships are connected to nature in that they open a view to a network of equal, (co)dependent and symbiotic relationships. The capitalist way of looking at nature is through a relationship of benefiting and dominating. Feminism does that through networks of companionships. Personally, I’m not even a big hiking-in-the-wilderness-type of a person—rather an observer of urban nature—but I think that’s also suitable for a feminist cause looking through a queer lens; strict dualisms, like natural versus cultural environment, are outdated in a way. Everything is part of one globe, different boundaries get stretched and reveal their artificialness. ‘The wilderness’ is in many ways penetrating the cityscape, and cities basically live off nature.

L: Can we change the topic slightly? I am wondering about your choice of medium. Maybe you could say more about what you think about comic art, and why this is a great medium for you? And what might it possibly allow, compared to other forms of expression?

J: It’s a terribly democratic art form for telling stories. It’s like that … when it really doesn’t need anything but paper and a pen. Somehow, I just enjoy drawing, and it feels natural. But somehow, it’s kind of the power of comics that keeps me fascinated over and over again. You can just sit at a table and need nothing more than paper and pen. At best, not even colours or anything. And then you can tell and show it all in pictures. It’s an incredible power. And then somehow … I also teach, so it’s kind of awesome when people start thinking that I’ve been thinking about a story like this and that, and then we start thinking together about how to pace it and how to fit it in the panels, and then people get excited, and it suddenly becomes a physical thing. And then others can look at the story that that person has had in mind. I think that is incredibly magical. I will never get tired of it.

L: And it’s perhaps more democratic in that it has no language boundaries. In a way, the image may translate to different backgrounds and cultures better than written language [does].

W: It’s really interesting that you bring up the word ‘magic.’ This is what comes to my mind when I think the art you make and your aesthetics. It’s magical and more than beautiful because there is something that I can’t put into words. You know, I can talk about the colours and the animals and then the humans and the animals that speak in your work and all of this, but there is another level that is magical and there is so much strength in this magical element in your work. And this is why Luca and I both really love your artwork: because it has this magical dimension. Shall we maybe talk a bit more about colour—your work is super rich in colour, deep greens, strong yellows, and so many more … and it’s kind of a signature of your work. But then there are also many blog posts in black and white. Could you tell us more about that?

J: That blog format served me as a sort of a training platform. So drawing in black and white is really simple in a way, and of course, incorporating colour requires thinking about colour. So, in the blog, I first practiced using colour, and then when I felt like I somehow mastered it, then came the power trilogy in colours. But then the blog returned to completely black and white at the point where I was really anxious. My father had been diagnosed with cancer, from which he has now happily managed to recover completely. But for some reason I was really anxious about it. And there was more to it: one of my friends died then, and all sorts of things. And somehow, I felt that colours were too much, that while at best it had been wonderful to immerse myself in those colours, and it has somehow been kind of colour therapy in a grim world, now they were somehow too much, and I had to drop them all because I couldn’t somehow handle it.

L: It’s a bit like when you’re depressed and it’s a really sunny day.

J: Yeah, yeah. I couldn’t deal with it. Everything had to be left out. Then I … Now, actually, it’s back to a situation where now … because I got excited about all that black and whiteness, because it has such a simple charm of its own, you can play with the contrast between black and white and get dramatic. But now I can kind of do both, and maybe don’t get so emotional about either. But there has been a connection between these things and the changes in use of colour.

W: It feels like your comic art is in many ways personal. Somehow there are characters from your life, like the dog, and very personal parts of life in the narrative, but also on the aesthetic level it reflects your personal life, from going from colour to black and white and back. So that’s a sort of like a different level of biographical work, right? Would you describe your comic art as in some way autobiographical on this aesthetic level?

J: Yes, there is always an autobiographical level. But isn´t art always? … [A]lways in art there is this level. It is impossible to make art in a really impersonal way. I’ve tried it … I mean I haven’t consciously done any autobiographical work anywhere other than the blog. My aim is to tell stories, fictional stories, but where I get the material … it is of course always myself in the end.

W & L: So, coming back to our conversation on the animals in your work and relating this to transness … There are a lot of animal characters in your stories, that talk, that interact with the human characters. It is even unclear if they are animals or human: they are so blended in their existence. Talking animals are a very old tradition in comics, there are the classics like Mickey Mouse and Calvin and Hobbes … But there is something very specific to it in your work because it connects to queer feminist and trans politics. Why is that important to you, those talking animals, especially when you relate it to your own gender identity and experiences with that in this world?

J: I think of this like breaking boundaries with one thing and the other thing. It is like mixing and smashing everything. And I try to do it all the time, mixing and smashing boundaries. And including animals in the way I do [is] one way of doing this.

W: Maybe by doing this mixing and blurring of boundaries you create a new world?

J: Or representing our world in another way. They are kind of a queer lens into our world, not a new world.

W & L: Yes, maybe the human animal characters are almost like a motif to show a new dimension, a new way of perceiving reality, worlding it differently…. It is maybe significant for the idea of queer and transfeminist utopian aesthetics?

J: Yes, but just to be clear, I don’t think I am creating a different world, but it is essential that I try to describe the existing world—that is, our world. Because human thinking works a lot through boxes, the thinking of all of us. But it is such a great accomplishment of queer feminism always trying to fade out those boxes and shuffle those boxes. And then you can do a full round and show the same box in a kind of a crazy light, exaggerated, almost grotesque…

W: Why is this particular element of grotesque exaggeration important here for the queer and transfeminist element? It also makes me think of camp, or drag culture…

J: For me this is because of its freedom. That freedom is at the heart of it all. When the artificiality of the boxes is made visible to everyone, sometimes, at some points, we can reach such a good situation that they stop defining us as power relationships—or in general stop defining us. That freedom is at the heart of it: power and freedom … but power has the ability to get a hold of us again, and those categories are always flexible, so it is about fastness, being quick and keeping moving.

L: So, I guess we just came up with a new slogan. So, what is there in the core of all of this, is the idea of freedom. And by being able to make visible how nonsensical these categories are and how kind of impossible they actually are, in the best-case scenario that creates these spaces or pockets of freedom, before the bigger institutions grab them back and kind of assimilate you back. But you have that kind of doorway somewhere, and that comes back to freedom. So, it is not necessarily something that is a permanent state of being, but kind of these moments of being able to critically challenge by showing that absurd nature of these categories, basically. But you have to be fast. Fastness and Freedom. That was the slogan…

W: I think I am grasping this importance of this critique in your work, as what makes the magic; it is like, you have a fundamental critique, and you really bring this into a small comic strip, the critique, and the beauty, and the creating of alternative spaces. And all of this happens in tiny pictures.

To finish, would you share with us how you think that nature and ecology, or the environmental crisis we are continuously witnessing, impacts your thoughts and your life, e.g. your thoughts on being non-binary in these times, a relationship to a threatened ecosystem… This is a super open question just in case it makes you think of something!

J: Recognising connectedness beyond the binary—between human and non-human live forms—is crucial for surviving the climate disaster, loss of biodiversity, and so on. We have to let go of the capitalist structures of ownership and subjugation, change how we understand economy and what drives it. Our relationship to the world in general. There´s lot to do and we cannot completely avoid the catastrophe because it is already happening all around us. But I do believe a lot is still salvageable.

W & L: Jiipu, thank you for this hopeful last comment. It was really wonderful to talk to you. Thank you for taking the time.

Notes

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey