Unravelling

by: Miki Shaw , March 30, 2023

by: Miki Shaw , March 30, 2023

***

The biggest challenge of motherhood for me was going from being entirely concerned with my own needs to being someone responsible for two people, one of whom was entirely vulnerable. You are thrown into an intensely demanding role that nothing can prepare you for. The experience takes you back to a very basic level of being where your whole existence is concerned with the physical aspects of life—eating, sleeping and toileting.

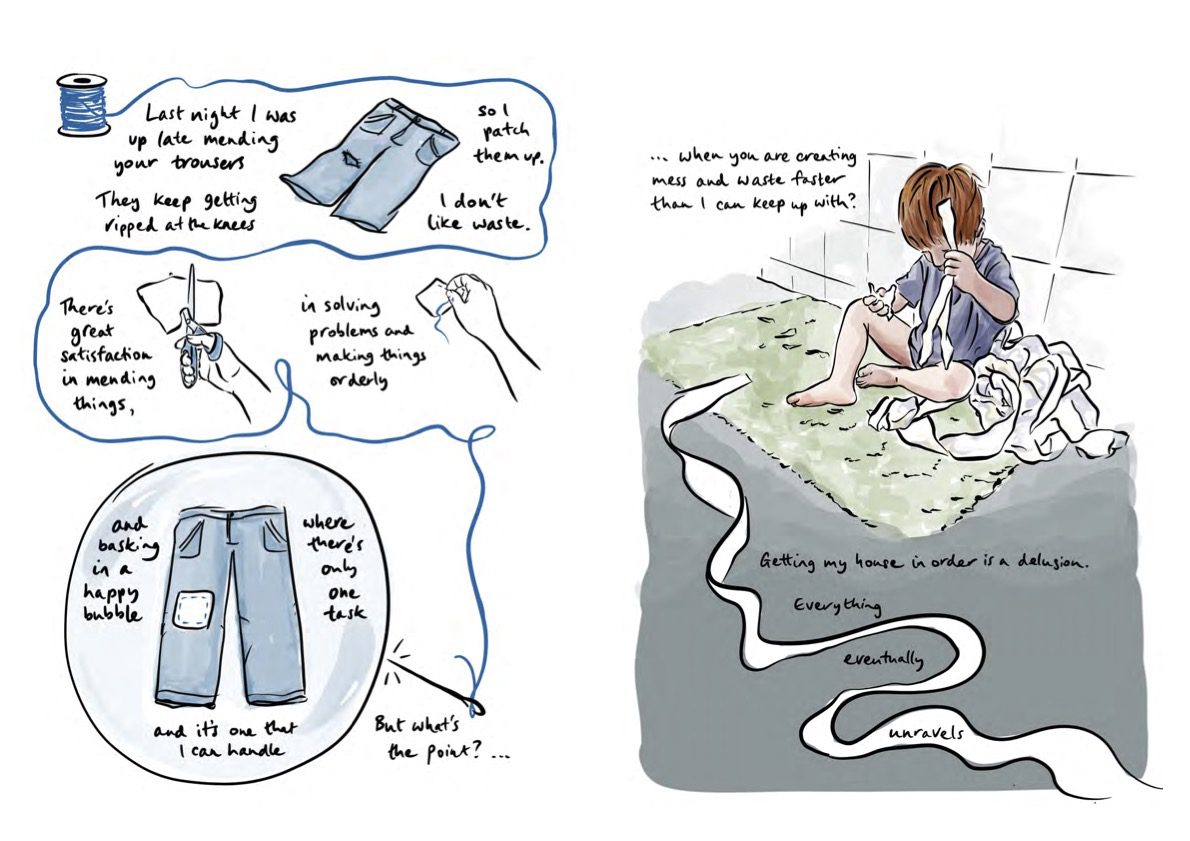

As an adult I always tried to transcend that level. I prioritised intellectual matters over bodily matters. Motherhood forced me to engage with the things I had tried so hard to avoid, leaving me with less time, space and energy for my creative practice.

Luckily, I have found tremendous solidarity with a group of women from a growing peer-support network called Mothers Who Make (MWM—see https://motherswhomake.org). I co-facilitate a local MWM group of artists, performers, writers etc. who are also mothers, and we meet once a month to support each other’s process and practice. One of our key objectives is to create a place where the people who attend are valued as being both mothers and makers. This is an unusual space because so many environments want you to embody one or the other. For example, if you take your child to a clinic, they just call you ‘mum.’ The nurse will ask you ‘does mum have any other issues today?’

If I join a gallery opening or artists’ networking group, it often seems to me out of place to mention I have a child. I feel that it diminishes my seriousness or commitment as an artist, and you certainly wouldn’t want to show up to any of those places with a baby. It does seem odd to me, because both motherhood and artistic practice are forms of creativity. Need they be mutually exclusive?

There is tremendous creative potential in integrating these two roles. In my life, I am interested in understanding the splits I have felt between opposing worlds and working to integrate them in new and fruitful ways. As a student, I felt the split of being a person who was drawn to computational sciences and also being drawn to art. I still feel that divide and recognise that most spaces today want you to choose between one and the other. Who decided we have to specialise and just devote ourselves to one side or the other, as if it’s a binary choice? Science or art. Mother or artist. Religious life or secular life. Maybe these were life choices embodied by old, white men who defined the ‘centre’ because of the power they held. I’m thinking, for example, of Charles Darwin who had many children but didn’t have to worry about them because women would take care of his offspring. He was free to focus on his practice, separate from his parenting. My own experience is much more enmeshed.

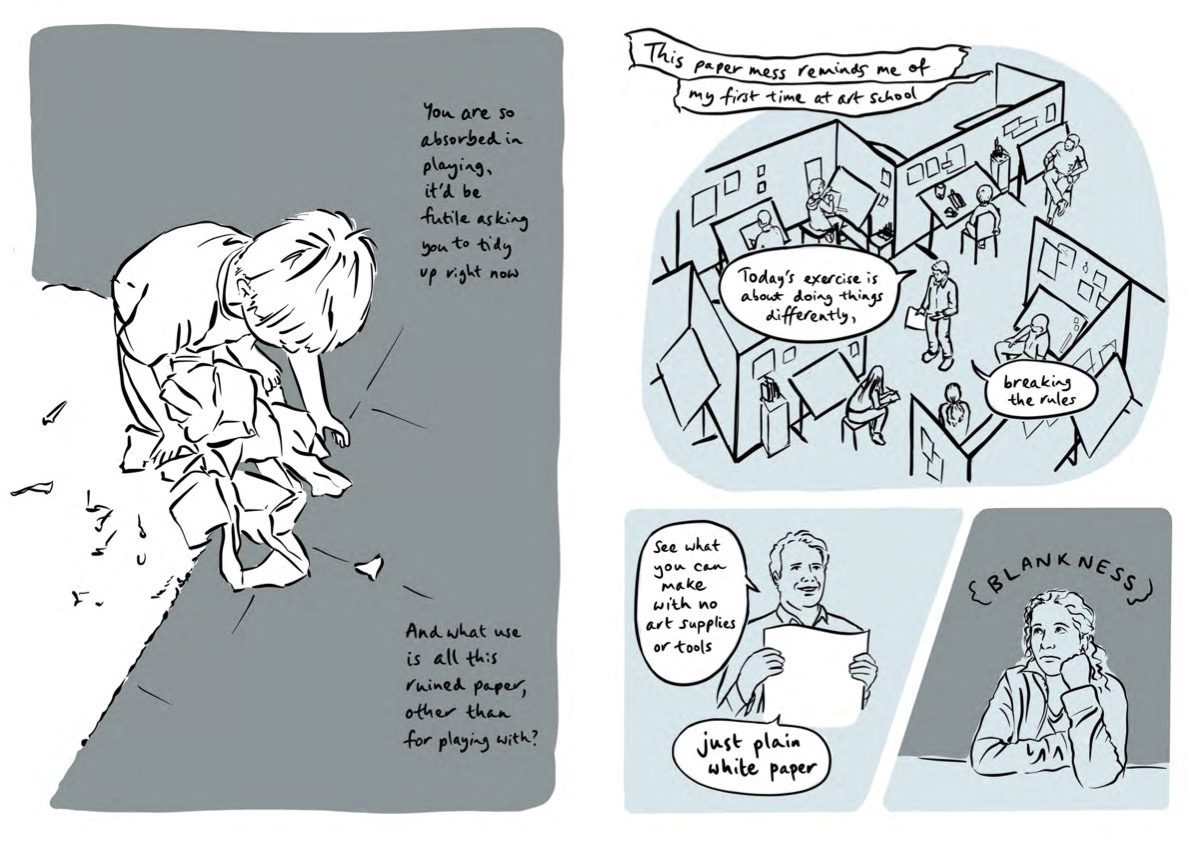

In any event, I was persuaded by my academic advisors to study Computing first at university because it was implied that Art could wait. After graduating I embarked on the art course I had originally wanted to do, but ultimately I felt out of place, and that my work lacked purpose. (This is the moment depicted in the art school flashback scene in my comic.) In the following years I found that as much as I tried to bring visual creativity into my career it was unsatisfying. This sense of lack was only resolved years later, when I finally returned fully to study art. I still feel the pressure to choose one end of the spectrum or the other, when what I really want to do is explore the enriching meeting point in the middle.

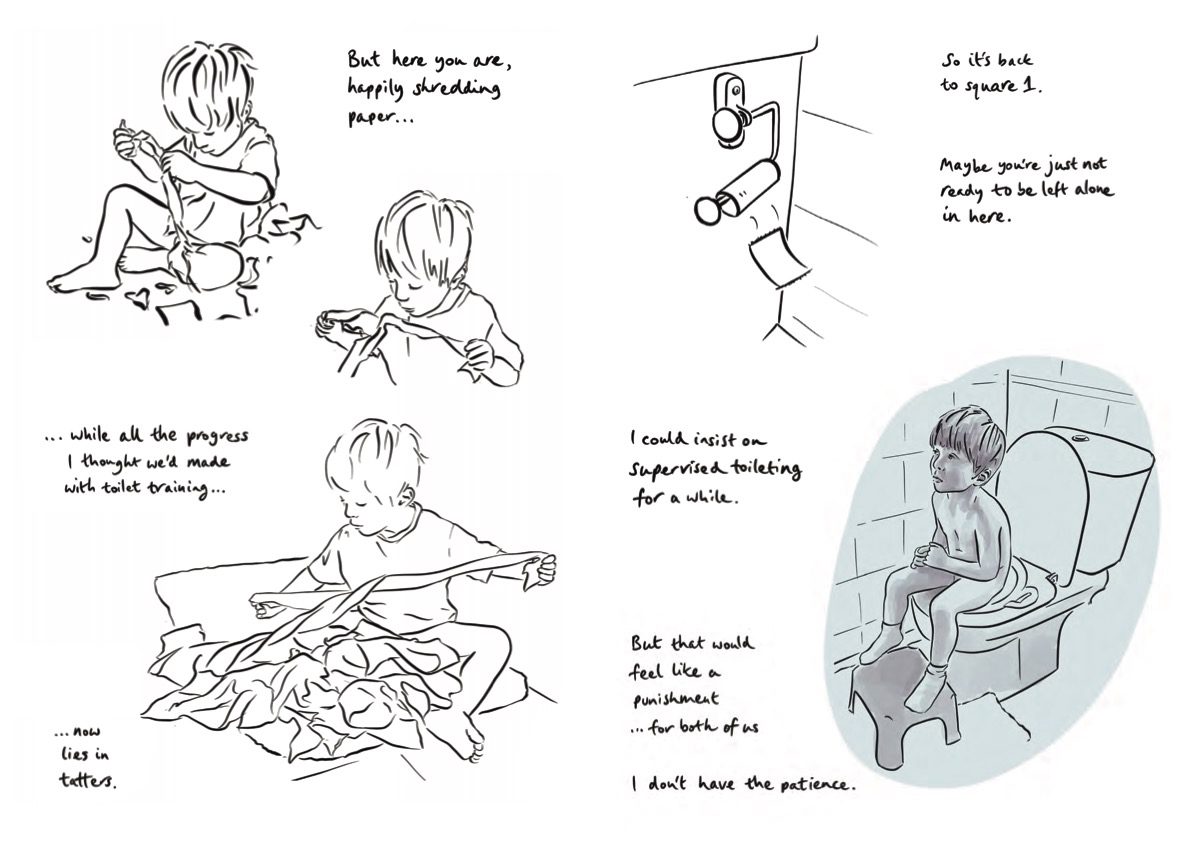

By the time my second child was born, I had completed my degree and had met more women who had walked this path. I was spending much of the day looking after, and at, my kids, in close proximity to them. So, it made sense to me to integrate them into my work. At first, I started drawing them from life but, as they started moving faster, I would take photographs of them, and when I had undisturbed time while they were asleep, I would draw from the image I’d recorded. There’s always a risk working from photographs that something of the ‘liveness’ is lost. So, I’ve adapted my techniques, using spontaneous gestures and fast pen strokes, to retain the animated feel of the original pose.

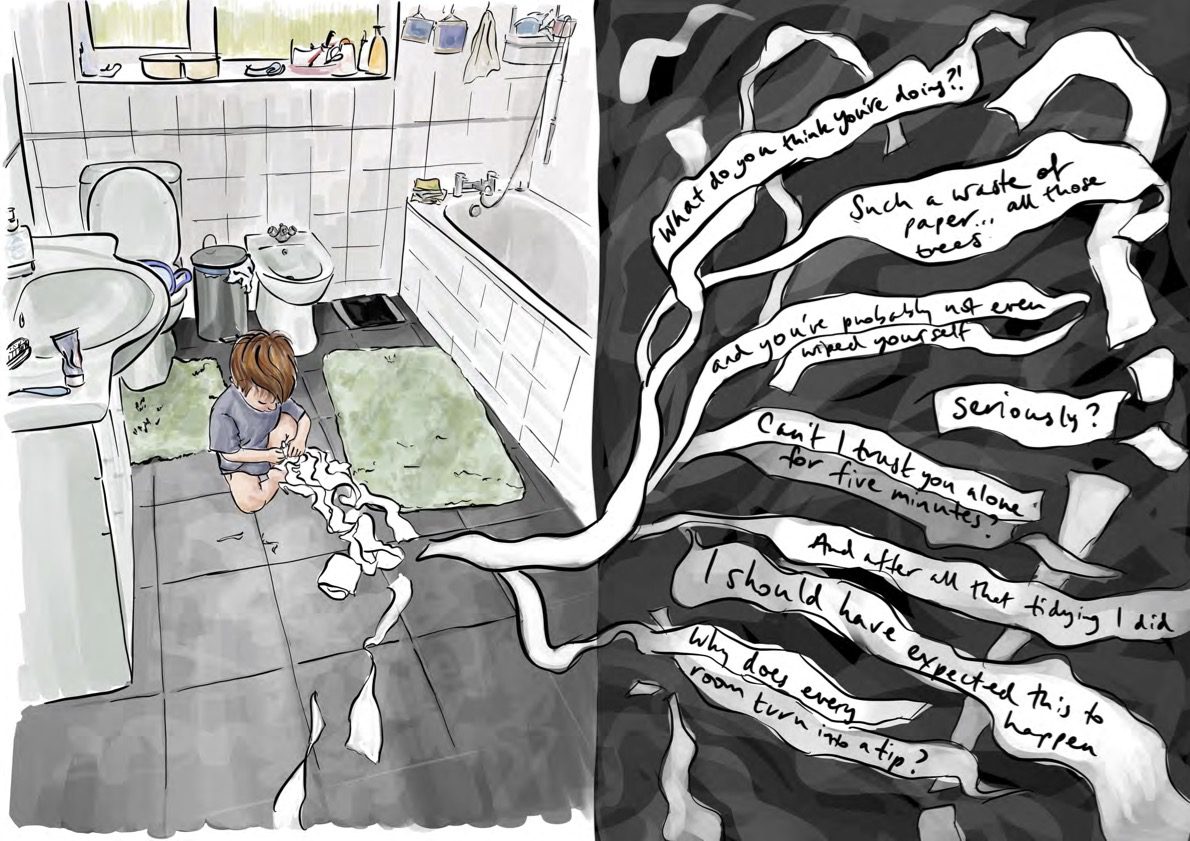

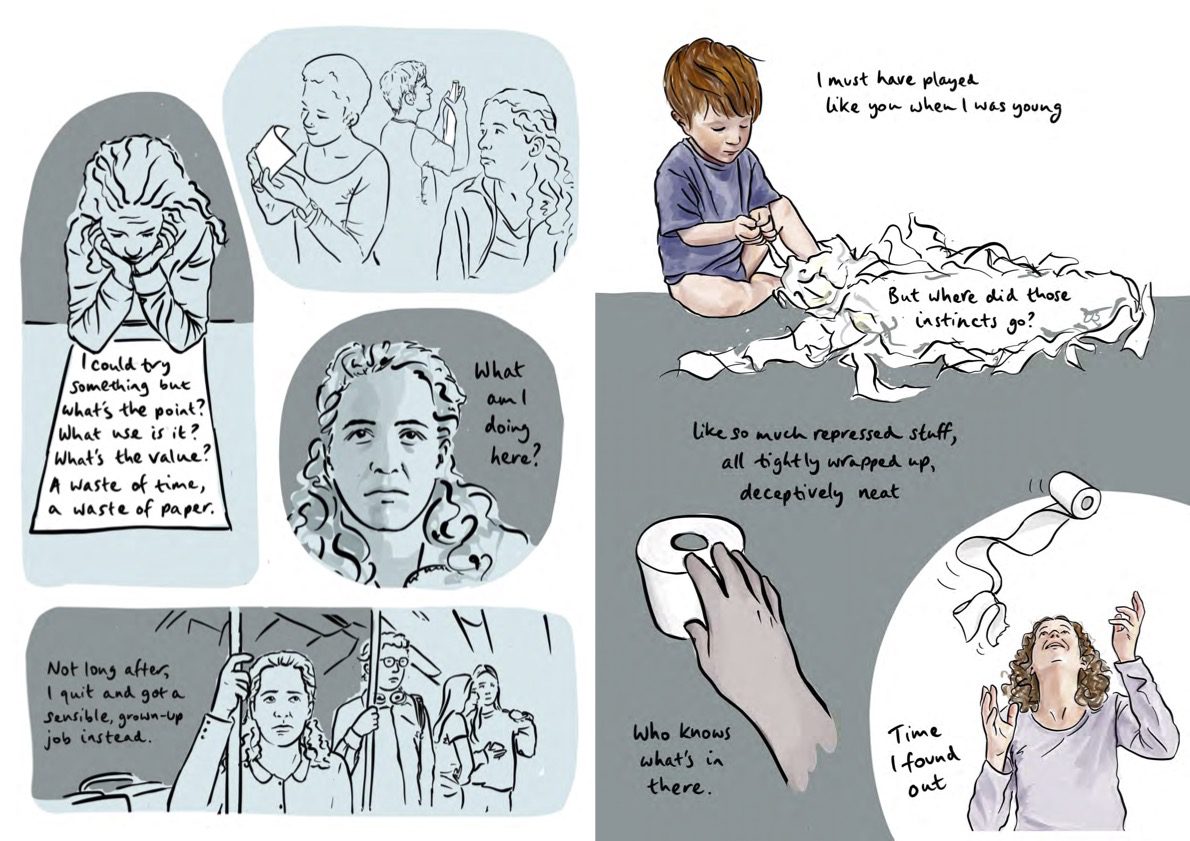

While drawing, I found myself asking this question: ‘What is it that I find so compelling about these particular poses?’ They were generally pictures of my child involved in some mundane, daily activity. I found it helpful to explore my thinking through writing; to put my own inner dialogue about what they were doing on paper. I saw questions emerging such as ‘why don’t I find playing with food as fascinating as they do?’ I saw that it was a route into my own various hang-ups, like the difficulty I have dealing with mess.

Having internalised all the messages about presenting womanhood in a particular way, I feel judged when people come into my house and it’s a tip. It’s all bound up with a sense of worthiness coming from being a ‘good’ wife and mother. I’ve also taken on the idealistic notions about ‘providing a stimulating and clutter-free environment for my child’ that I read about in parenting handbooks. In these books, the mother is often presented as the problem. (Child not sleeping? You’re doing it wrong).

In my work, I am outing that critical voice and expressing my confrontation with it on paper. I am also using the reminders of my own childhood now as provocation or material in my art. It is an urgent topic for me that I want to excavate through my stories. I’ve also found it validating to see how my work resonates with others, such as those in MWM. As much as these are stories for mothers, they are also stories for anyone who has ever been mothered.

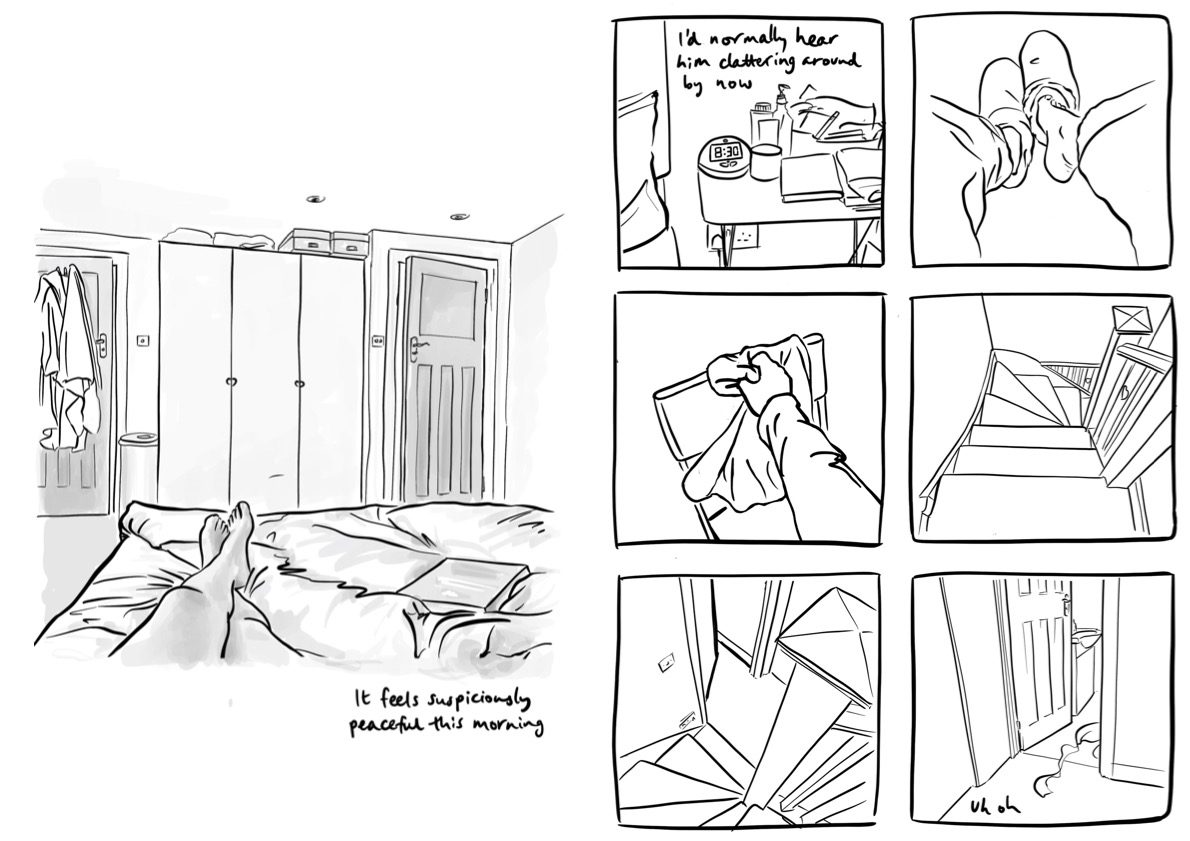

In Unravelling, the first chapter of a longer work in progress, I explore the onslaught of feelings I have towards my child who is absorbed in creating a mess. An initial sense of outrage and frustration gives way to hopelessness and then curiosity about the source of these strong emotions. My work is inspired by, and in conversation with, other autobiographical comics. Polly Dunbar’s Hello Mum and Joe Decie’s Collecting Sticks address everyday moments of parenting introspectively, acknowledging the unpredictability and emotional turbulence of life with children. My writing process challenged me to unearth and identify difficult feelings. I have benefited from different approaches in autobiographical comics exploring these, such as Allie Brosh’s self-deprecating reflections of her own sense of failure and Sarah Lightman’s honest portrayal of the weight of family expectations and disappointment. Roz Chast applies raw humour to poignant effect in Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant, when she confronts her role as both child and carer for ageing parents. The works I’ve referenced above all present different takes on parenting, ‘adulting,’ or growing up. What they all have in common, and what I aim to realise in my own work, is revealing the internal emotional conflicts that daily life presents when coming to terms with the responsibilities and challenges of one’s familial role as partner or parent.

Seeing my child play, so freely, and with no sense of consequences is what kick-started this story. I realised that over time, that state of play had become less accessible to me. That invitation has been withdrawn from me as an adult, a mother for whom time is a balancing act between looking after the needs of another person and my own. I’m thinking wryly now of men like Darwin or Gaugin. I can’t sail off to the Galapagos to develop a theory of evolution or leave my children behind to paint women in Tahiti. So I find my art where I am.

REFERENCES

Brosh, Allie (2013), Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Gallery Books.

Chast, Roz (2014), Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Bloomsbury.

Decie, Joe (2017), Collecting Sticks, Vintage Publishing.

Dunbar, Polly (2021), Hello Mum, Faber & Faber.

Lightman, Sarah (2019), The Book of Sarah, Myriad.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey