Site & Sound, Wall & Window: The Material Milieu as Emotional Enclave in Documenteur (1981)

by: Ulrike Hanstein , October 5, 2023

by: Ulrike Hanstein , October 5, 2023

Introduction

Los Angeles is an island—all movements through its spaces and all conceivable aspirations come to an abrupt end at the ocean. Or at least this sense of isolation and enclosure is the experience of Los Angeles that Agnès Varda’s film Documenteur puts across. Documenteur was filmed on location in several neighbourhoods of Venice, California, in the winter of 1980. Given the unpretentious cinematography with little extra lighting, as well as the colour and grainy texture of this 16 mm film, the images bear the physical traces of a small-scale production. Thus, the images support a strong sense of connectedness to the material reality ‘out there’—that is, the everyday life and the brief encounters with strangers in the streets, alleyways, shops, and neglected residential settings of Venice.

Varda’s film centres on a French woman called Émilie (Sabine Mamou). The plot provides meagre information about Émilie’s past and about her relationships to the people she meets. The film follows the protagonist and her son Martin (Mathieu Demy) as they look for a place to live and then settle into a small apartment. From the characters’ dialogue and from Émilie’s internal monologue, which is presented in voice-over, we learn about her American former lover Tom and the couple’s break-up. The film’s attenuated narrative revolves around Émilie’s process of grieving for the lost love, and for the erotic and emotional bonds left behind. A subdued atmosphere of sadness and nonaction is invoked by the film’s composition of rather uneventful, mundane episodes. These episodes are presented as a series of distinct spatiotemporal intervals with loose causal links between them. Documenteur displays the characters’ encounters, gestures, and interpersonal relations as taking place—as being located—in a specific constrained, urban space. Through framing and the images’ well-balanced composition the visual space appears solid, compact, and compressed. And yet against the unalterable bindings of material space and the tight framing of the visual field, time is seemingly flattened out. The slow pace of the unfolding narrative hesitantly arrives at the point where screen time measures up to the real duration of bodies moving in and across space.

Varda’s site-specific mode of filmmaking is grounded in the tangible characteristics of the built environment. Her cinematographic practice draws on the material resources of the urban space and explores the actual architectural structures in their role of supporting specific spatial, perceptual, and affective relations. Varda’s preoccupation with real places is integral to her film aesthetics on three levels. First, the attentiveness to the incidental details and physical attributes of actual locations is a strategy that supports her resourceful alternative mode of production. Second, the film form of Documenteur proposes a visual correspondence between the female protagonist’s perceptive subjectivity and the architectural settings as a concrete manifestation of the external world. Third, Varda’s materialist and poetic exploration of space mingles documentary with fictional codes of representation and amalgamates the respective compositional procedures.

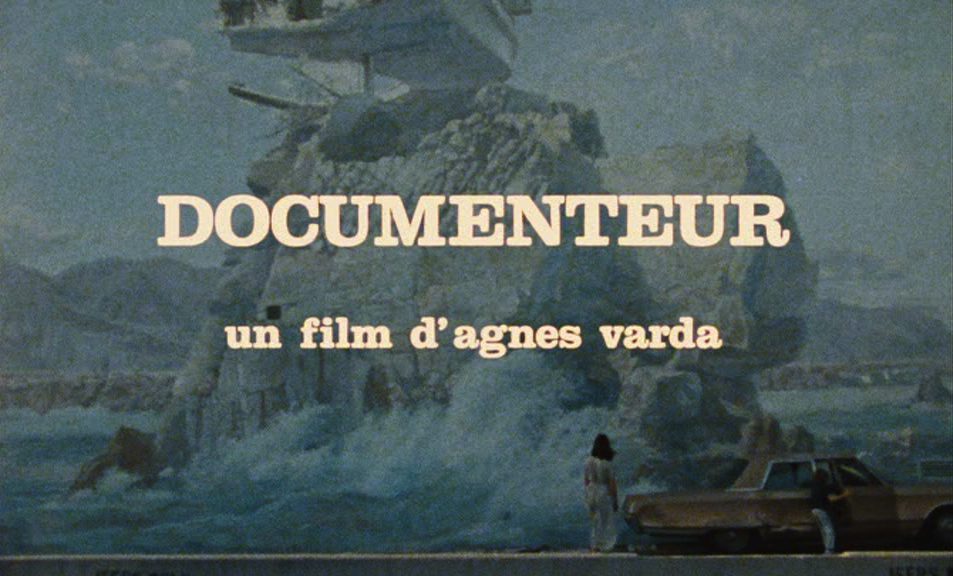

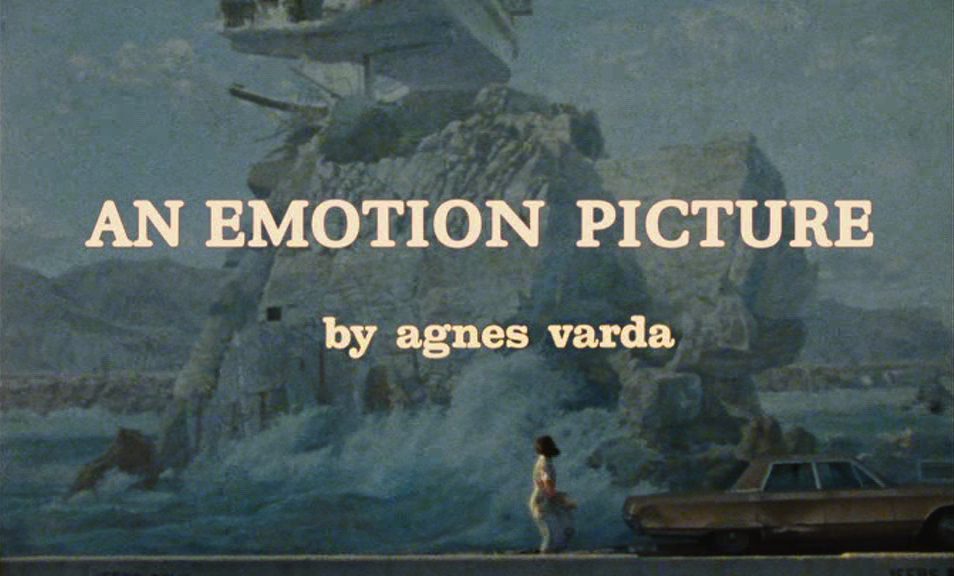

Fig. 1: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 1: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 2: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 2: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

The title sequence of Documenteur presents a subordinate title like a motto for the film. The main title ‘Documenteur’ is followed by the caption ‘An Emotion Picture.’ In this phrase, the additional single phoneme transforms the signifier. The new configuration of letters and sound plays with a slippage between words, code, and meaning. The title sequence links the common term ‘motion picture’ to the dynamics of mental agitation and feelings. So, how should we understand the aesthetic form of ‘an emotion picture’? Does Varda’s site-specific mode of filmmaking convey or formalise emotionality? What are the film medium’s specific means of linking physical and cinematographic spaces? And how are we as viewers situated and moved by the film’s expressive materiality—that is, the audio-visual forms, which propose emotional entanglements between real environments and the protagonist’s embodied subjectivity?

My essay explores the ways in which the emotion of sadness manifests itself in the moving images and in the film’s form. I shall take a closer look at several scenes from Documenteur to demonstrate that a subject’s remove from the world in the process of grieving is reimagined by means of spatial relationships of isolation and enclosure. In Documenteur static long takes and slow parallel traveling shots render space as obstacle and distance, as disconnection and unalterable interval between the characters, between the characters’ eyelines and the camera, between successive shots, between image, voices, and music, between words and tangible objects, between English and French, between the visible surfaces of the urban environment and the subjective space of memories and emotions. Briefly, the moving images as articulate developmental forms propose a particular emotional apprehension of spatial relations—that is, a sad withdrawal from practical involvement and a sense of diminished affective attachments to the world.

The Matter of Film Space

Varda’s visual mapping of environments has instigated insightful scholarly debates. In their nuanced analyses of Varda’s work, Alison Smith (1998), Kate Ince (2013), and Delphine Bénézet (2014) argue that sensory perceptions and embodied experiences of space—as vast terrain, social milieu, historic site, ecology, local community, urban habitat, or landscape—are of singular import for the filmmaker’s corporeal cinematic worlds. Many of Varda’s feature films, documentaries, and short films emerge from a phenomenological understanding of lived urban and rural environments. The images display characters’ embodied experiences and register their mundane or poetic responses to the specifics of sites. In her illuminating discussion of Varda’s work Smith points out that ‘[o]ne strand of Varda’s filmmaking consists in presenting the subjectivity of a principal character through her perceptions of her surroundings’ (1998: 60). Simultaneously foregrounding protagonists’ inner feelings and thoughts and the visual dynamics of actual places, Varda’s films present the directional movements of embodied acts of perception. Drawing on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s work and contemporary film philosophical discussions of embodiment Ince defines Varda’s approach to moving images as ‘a performance of feminist phenomenology … a carnal cinécriture’ (2013: 613). As viewers we discern the characters’ bodies as sites of sensing, seclusion, and engagement with the world. They appear as limited and placed, as acting on and responding to their surroundings. Thus, Varda’s inventive audio-visual forms reveal how people and places implicate each other.

Thus far, scholars’ critical debates have shown the close linkages between Varda’s site-oriented filmmaking practice and her focus on women’s experiences and female voices. Smith, Ince, and Bénézet conceptualise the corporeal images as a situated sensory realism. They elaborate on the personal and political aspects of Varda’s spatial-aesthetic film practice. In so doing, they explicate the relational feminist ethics, which is manifest in Varda’s manifold works. My discussion of Documenteur proposes a subtle shift in emphasis: away from the focus on female authorship and embodiment toward the formal reflexivity of feminist avant-garde film practices. This entails a closer look at the traffic of ideas between feminist film criticism and women’s experimental filmmaking in the 1970s. I contend that Varda’s exploration of the materiality of the filmmaking process can be put in dialogue with the feminist avant-garde cinema, which deprivileged mainstream cinema’s models of expressivity and reconfigured the relationship between the camera, film space, and experiences of spectatorship. This approach links the question of film’s formal constructions of a perceptual space and particular viewing positions to a wider cultural field of cinema, in which mainstream modes of production and a variety of alternative film practices coexist. As David James has shown for the minor (or: countercultural) cinemas of Los Angeles, nonindustrial, independent, amateur, and avant-garde films articulate complex and highly ambivalent relationships to the hegemonic film industry (cf. James 2005: 11–19). Although alternative filmmaking practices might strive for radical otherness, they cannot isolate themselves from any contact or implicit negotiation with the codes, expressive forms, and cultural dynamics of mainstream cinema. Rather than perpetuating clear-cut distinctions between commercial and auteurist cinemas’ narrative and experimental forms, I consider these concepts as changing, as endlessly negotiated through specific encounters between aesthetic and theoretical articulations. Moving through a range of documentary, fictional, and essayistic forms Varda’s nonconformist work suggests that we understand cinema as a force field of highly divergent artistic practices. Her films incessantly generate new ideas of cinema as a poetic and narrative, personal and public, sensuous, and experimental medium.

In her seminal essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ Laura Mulvey analysed mainstream cinema as a patriarchal technology of looking, catering to heterosexual male scopophilic desires. Since the essay’s publication, Mulvey’s uncompromising ‘destruction’ (1975: 7–8) of Hollywood’s visual pleasures has been extensively discussed, reappraised, and revisited (cf. Mulvey 2019: 238–255). Her analysis of the symbolic order of cinematic visuality became a fundamental reference in film studies. Notwithstanding, the essay’s call for novel filmmaking practices has rarely been tackled. In her text Mulvey thinks of new technologies as an alternative to the industrial model of filmmaking, which links the substantial investment of capital to socially formed economies of desire. She notes: ‘[t]echnological advances (16mm, etc) have changed the economic conditions of cinematic production, which can now be artisanal as well as capitalist. Thus it has been possible for an alternative cinema to develop’ (Mulvey 1975: 7). Mulvey acknowledges instances of formal reflexivity in classic Hollywood cinema. Yet, for her the prospect of a politically and aesthetically radical cinema presupposes its autonomy from capitalist relations of production. Mulvey points out that avant-garde cinema’s countercultural stance towards mainstream film or its overt negation of the hegemonic film industry still articulate a connection to it: ‘politically and aesthetically avant-garde cinema is now possible, but it can still only exist as a counterpoint’ (1975: 8).

For Mulvey a political film aesthetics means new, anti-capitalist, and anti-patriarchal models of film production. After her thorough analysis of mainstream cinema’s structure of looking, she returns to the politics of artistic practices. At the very end of her essay Mulvey states, ‘[t]he first blow against the monolithic accumulation of traditional film conventions (already undertaken by radical film-makers) is to free the look of the camera into its materiality in time and space and the look of the audience into dialectics, passionate detachment’ (1975: 18). Mulvey proposes aberrant acts of looking as means to reinvent cinema’s codes of visibility, mode of address, and model of spectatorship. Her essay is closely connected to her own visionary film projects. Mulvey’s and Peter Wollen’s 16 mm films Penthesilea (1974) and Riddles of the Sphinx (1976) are radically original contemplations on acts of looking. Through long takes, 360° pans, and the intricate choreographies of tracking shots, the camera is released from mainstream cinema’s conventional techniques, which subordinate the framing and succession of the shots to characters’ eyelines. Rather than negating the absent origin and technological preconditions of the imagery, in Penthesilea and Riddles of the Sphinx the camera is featured as a material agent, as a cause of activity and expressivity in time and space.

Mulvey’s films and her theoretical reflections on the materiality of the camera make it clear that the innovations of feminist filmmaking practices in the 1970s moved beyond questions of women’s representation, sexual differences in forms of seeing, female spectatorship, or dynamics of desire. As avant-garde filmmakers sought to deconstruct mainstream cinema’s ideological functions, their works introduced new relationships between the camera and performers, movement and stasis, the material process of production and the filmic space of vision and voice. Aesthetically vanguard works like Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses (1964–1967), Yvonne Rainer’s Lives of Performers (1972), Chantal Akerman’s Hotel Monterey (1972), VALIE EXPORT’s Adjungierte Dislokationen (1973), Gunvor Nelson’s Moon’s Pool (1973), or Joyce Wieland’s Solidarity (1973) advanced alternative models of representation, screen performance, image space, visual narrative, exhibition, and spectatorship. Rather than constructing a unified and self-contained film space, these works make the spectators’ relation to the imagery and their self-aware sense of the possibilities and limits of cinema’s identificatory processes a crucial part of the viewing experience.

Documenteur interlaces autobiographical references with fictive characters, documentary images of the contemporary urban environment with narrative action, and an introspective voice-over with shots that keep the protagonist at an insurmountable distance. Varda’s film does not follow pre-set modes of representation and resists any simple categorisation. Documenteur transforms the codes of narrative film as the imagery seemingly drifts off from forward moving action and goes through insignificant details of places, stillness, and intervals of disconnected blank appearances.

A View of Venice

Documenteur begins with a static long shot of Émilie and her son, set against the backdrop of the huge mural Isle of California (1971–1972) by the artist collective LA Fine Arts Squad. [1]

Fig. 3: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Covering the side of a three-story building, the mural displays a post-cataclysmic vision of Los Angeles in faded oil colours. The metropolis is apparently in ruins and devoid of any living creatures. All that is left of Los Angeles’ architectural landmarks and its vast urban structure is a single rock with the remains of a shattered freeway. This ‘disaster mural’ envisions the region formerly known as Los Angeles as a deserted, uninhabitable, and inaccessible terrain surrounded by the ocean.

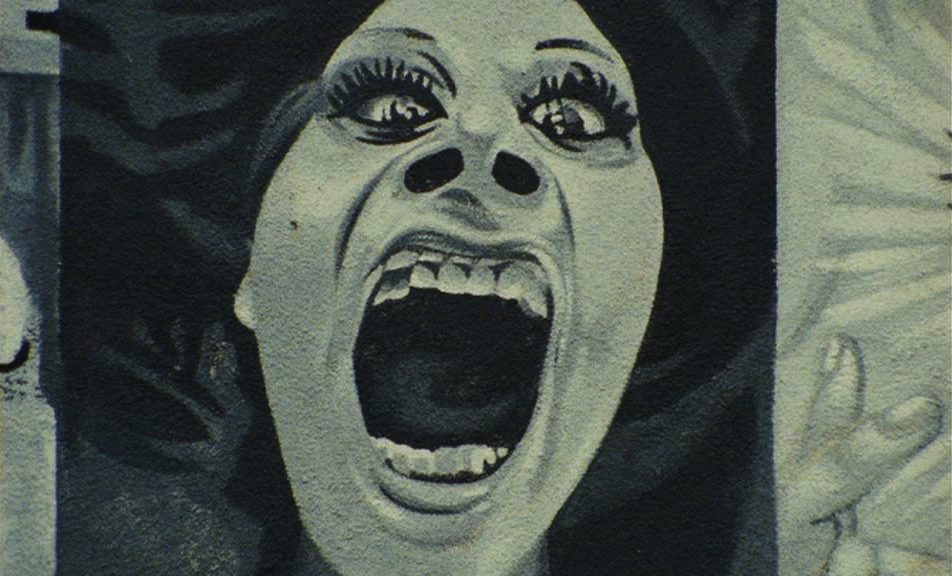

Used as a painterly backdrop in the film’s first scene, the mural introduces a pictorial image and a second perspectival view in the shot’s framed visual field. Clearly, the appropriation of the mural as a setting for the characters’ actions constructs a complex space of vision. The compositional cinematic image draws together stasis and movement, as well as pictorial and photo-filmic techniques for mediating vision. The contrast between the monumental mural and the small human figures provides the viewers with a sense of the real space’s proportions and of the camera’s distance. The following shots show murals by Willie Herrón III. A series of close-ups centres on particular details of the murals and features painted faces.

Fig. 4: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 4: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

As the limits of the walls on which the murals are painted are left out of the shots, the murals’ overall composition and size, as well as their architectural environment, remain unspecified. At the beginning of Documenteur murals are introduced as located, but cinematically reframed pictures. Murals recur throughout the film as expressive surfaces of the urban space. In the film’s first sequence, the forward narrative movement appears to be triggered by the resemblances of visible shapes, which link the wall paintings to the real three-dimensional space. Successive shots move from painted portraits to medium close-ups of men fishing on Venice Pier.

Fig. 5: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 6: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

On the soundtrack, Émilie’s continuing interior monologue ties together the series of disparate shots. Her expressions connect her feelings of loneliness to the strangers’ inscrutable faces.

Fig. 7: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 7: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 8: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 8: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

In this scene, Émilie’s narration shifts between the first and third person pronouns when she voices her sense of isolation. Émilie’s contemplation reveals that to her, the world appears disjointed. Everything seems fragmented into solitary words and isolated faces: ‘Là où je suis, il y a seulement des mots et des visages. (Where I am, there are only words and faces).’ [2] Émilie’s impressions of incoherent series of words and visions is conveyed by the parallel grammatical structure of her sentences: ‘Des visages seuls, des visages en liste, des paquets de visages, des mots seuls, des mots en liste, des paquets de mots. (Lone faces, lists of faces, groups of faces, lone words, lists of words, groups of words).’ In Émilie’s interior monologue repetitive patterns seemingly replace more elaborate combinations of words and nuanced expressions. Lists, alliterations, and accumulations of words indicate the character’s wandering thoughts and reveal her improvisational relationship to language: ‘Des mots qui sont des émotions, désir, douleur, dégoût. Ou alors, peur, peine, panique. (Words that are emotions. Desire, distress, disgust. Or fear, pain, panic).’ The voice-over narration enacts Émilie’s emotional turmoil and her sense of isolation. The protagonist is introduced as a somehow distracted, passing observer of the myriad details of everyday life: ‘Elle passe, elle regarde. (She passes, she looks).’ In the scene at the pier, the editing strongly emphasises the character’s ever-changing, dissociated impressions. The disruptive montage of images does not strive for spatial continuity and operates without eyeline match patterns. Rather than interweaving shots of Émilie looking and shots of what she sees, the successive shots display disconnected views on the place and tightly framed figures. Eventually, Émilie and Martin are shown as part of the small casual crowd, which meets on the pier to fish.

Fig. 9: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 10: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

After that, the pier and the ocean are shown in medium long shots. These images allow for a wider view of the oceanfront, and they rhyme with the film’s establishing shot—the mural’s vision of a rock surrounded by the ocean.

In Documenteur the visual presentation of space seems to result from a documentary approach to the actual architecture and the inner workings of the local environment. Similar to the scene at the pier, the fictional characters for the most part intermingle with the factual social life and the ‘afilmic’ space of the built environment (cf. Souriau 1951: 234). Thus, the actors paradoxically appear as extras throughout the film—that is, as a fictional and carefully staged supplement to the already existing locales and gatherings of strangers in the street. According to the film’s imagery, the neighbourhoods of Venice are neither scenic nor picturesque. Documenteur does not show landmarks like Abbott Kinney Boulevard, the boardwalk, or the canals. The film captures the then-transitional phase of the community, after the era of beatnik and hippie bohemia, after the Doors had met and lived in Venice, yet still ‘people are strange when you’re a stranger,’ and ‘streets are uneven when you’re down’ (The Doors 1967).

As a visual record of the urban district in 1980, the film shows Venice before the major redevelopment of the canals and the rampant gentrification of the last twenty years (cf. Deener 2012: 69–91). Venice is presented as a highly diverse community, where artists, workers, homeless people, and different generations of immigrants live in contiguous spaces. Documenteur depicts Venice as an enclave isolated from adjacent environments and the overall urban structure. Viewers see the pier, an oceanfront house, kitchens and bedrooms, courtyards and gardens, streets and alleyways, palm trees in the rain, a barber’s shop, a diner, a Laundromat, a schoolyard, and warm light glowing in the windows of bungalows at night.

Walls & Windows

In an interview Varda summarises Documenteur as ‘a film about words, exile, and pain’ (Varda 2014: 108). Varda wrote, directed, and produced the film. She worked with a small crew of long-term collaborators, including Nurith Aviv (cinematography), Sabine Mamou (editing), and Georges Delerue (music). In a conversation with Emmanuelle Loyer, Varda elaborates on the autobiographical components of the narrative and on the reserved, mournful protagonist, who epitomises a specific tone of Los Angeles for her: ‘an introverted Los Angeles, that is sad, desperate’ (2012: 03:35–03:39). Varda explains that she ‘tried to film pain. As if one could film pain. The pain is disproportionate. There is more pain than being separated and looking for a flat. But that disproportion is what the film is about’ (Varda 2012: 06:35–06:52). Varda then discloses that she and her director of photography jointly ‘aimed for shots that hurt. And we had fun doing it’ (2012: 07:24–07:29). Documenteur projects the protagonist’s inner reality and her painful feelings of loss in external, mundane forms. The mise-en-scène and the cinematography make elaborate use of walls, corners, doors, and windows of the built environment. As shapes, scales, volumes, colours, textures, sources of lights, reflections, or solid boundaries the built environment essentially constructs the film’s emotional geography of separation and solitude. By commenting on three scenes with slow parallel tracking shots, I aim to demonstrate how the cinematography relies on the existing architectural structures.

Fig. 11: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 11: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 12: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 12: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

A scene, which starts eight minutes into the film, shows Émilie looking for an apartment to rent (08:30–09:44). A medium long shot presents the façade of a weatherworn stucco cottage and a small patch of lawn in the foreground. In voice-over we hear Émilie’s interrogative reflections on idiomatic expressions for a house, followed by the remark that she needs a cheap place to rent. A slow camera traveling to the left sets off. The camera first reveals the open space to the left of the house, then the façade of another identical house becomes visible and blocks the view. The ongoing tracking shot then catches up with Émilie walking in the foreground, as the third identical house comes into view. Up until this moment the regular pace of the traveling shot, and the camera’s unchanging distance, evoke impassive, registering scrutiny. In the following, the camera responds to the character’s stops and movements with slight horizontal pans. Thus, the figure appears to be trapped by the camera, which then attentively keeps the forward-moving figure in the centre of the frame. Nevertheless, the camera remains at a distance. This sense of detachment is reinforced by the lack of ambient sounds. When Émilie resumes her walk after a brief pause, the voice-over ends, and piano music begins on the soundtrack. The musical beat corresponds to the visible beat: the repetitious rhythm of her feet hitting the ground. Like the audible voice the music evokes an intimate proximity to the sound’s source and defines acoustically a near and enclosed space. Thus, the voice and the music construct a region that is somehow displaced yet confined, which seems much closer to us than the distant views.

In this scene, the introspective and contemplative dimensions of the voice-over might be best understood with reference to Christian Metz’s elaborations on the ‘I-voice’ (voix-je) (2016: 107). Metz defines the I-voice as the voice of a film’s character, using the pronoun ‘I,’ whose speaking is presented to the viewers without a visible representation of the body, which might announce the act of speaking explicitly. According to Metz, the I-voice is at the same time located in intimate proximity to the film’s diegetic world and dislocated, transcending the images by which this world comes into view. The I-voice seemingly sees everything that we see as viewers. Yet, the voice appears to be absent from the presented action and does not intervene in the ongoing events. Metz’s work on the I-voice points out the ambivalent experiences of intimacy and dissociation, which the voice-over as a cinematic form might bring about. In Documenteur Émilie’s voice-over narration encapsulates her distracted and non-possessive way of looking on, and it strongly evokes a sense of detachment from the repetitive patterns of everyday life.

In the scene, which presents the protagonist walking, the tracking shot gradually inspects a series of bare and bleak houses under a cloudy sky. The images’ unpretentious rendering of these dwellings corresponds to the voice-over’s minimalist description of a house ‘une cube, une porte, deux fenêtres (a cube, a door, two windows).’ The tracking shot displays the monotonous row of built boxes, and carefully measures out the space between them. The camera’s fixed distance to the characters forecloses any dramatisation or psychological explanations. Due to the shot’s scale the figures are shown as embedded in—and bound to—the material surroundings. Since we do not hear the dialogue, the characters’ interactions are reduced to something that simply takes place. We see small gestures, shifting distances between bodies, and their postures and orientation in space.

Fig. 13: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 13: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 14: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 14: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Some minutes after this scene, the duet choreography for camera and characters is repeated with minor variations (12:15–13:13). This time we first hear a brief dialogue between Émilie and Martin and some traffic noise. When the camera’s traveling movement to the right sets off, the acoustic sphere seemingly recedes from the visible space, again. We hear piano music, tedious repetitions of words in voice-over, and after that a repetition of the musical theme. At the scene’s ending, the camera does not follow the characters’ walk into the bungalow village. Rather, it pulls back in the opposite direction, widens the view on the low buildings and the sky, and noticeably increases the distance to the small group of figures in the background.

A third scene with a lateral tracking shot surveys the maze of backyards and passageways in the village of bungalows, where Émilie and Martin have settled (28:35–29:07). First, we see the junction of two streets in a medium long shot. The façade of a yellow stucco house occupies the left side of the image. On the right, we see the sidewalk and the street with palm trees and parked cars. A small boy in the background walks to the left and disappears between two houses. When a tracking movement to the left begins, the camera seems to take over the direction and pacing from the boy’s movement through the space. In close proximity, we see the yellow wall of the house and the lower parts of a window. Then, Martin enters the frame from the right and moves along with the camera to the left. He gaily climbs up the steps to a door, jumps from the landing down to the street level, and continues his walk to the left. The dynamic of the body, rising and falling within the frame is counterpointed with the continuous horizontal movement of the tracking shot. Then, the boy and the camera arrive at the corner of the house. The visible space opens into a confined passage between adjacent houses.

Fig. 15: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 15: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 16: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 16: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Martin turns to his right, runs away from the camera, and disappears behind the rear corner of the next house. The character is lost, and the camera then seems to follow its own trajectory of interest. It moves on along the next house’s light blue stucco façade, showing a window, a door, and another window while passing.

Fig. 17: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 18: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 18: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

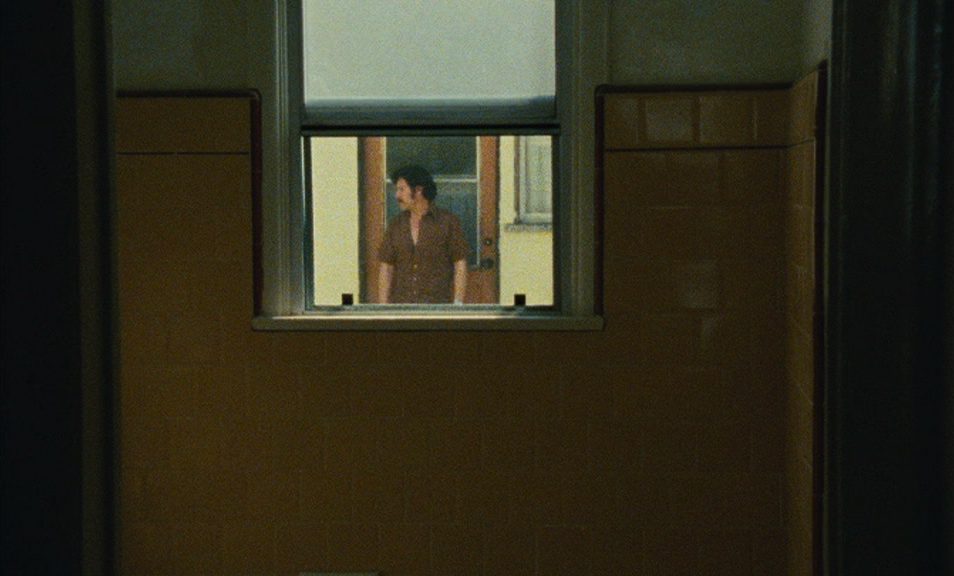

Behind the corner of the blue house Martin reappears in the passageway. He approaches the camera, turns to his right, and walks along with the tracking shot to the left. Eventually, the camera comes to a halt and loses the boy, who walks further to the left into the off-screen space. After a cut, a medium long shot presents the small interior space of a laundry room. Through the apertures of a window and a door Martin becomes visible on the right side of the shot as he approaches the building.

In the tracking shot, the hide-and-not-seek choreography of the kid and the camera renders the houses’ solid walls as obstacles, as blocking the view and as a limit to possible movements across space. The camera seemingly registers everything that is there on the spot to be seen indifferently: the walls and the walking, the distant and the near, stucco surfaces and deep spaces. The camera does not explore the space by following the character’s route. Rather, the camera’s nonintrusive and non-possessive way of looking out and moving on diminishes the hierarchy of the character’s action and the surrounding space.

Fig. 19: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 19: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

At the end of the scene, the openings of the window and the door set up a visible and acoustic connection between the indoor and the outdoor space. Here, the material configuration is transformed by the perceptible dynamics of seeing and listening, which overcome the spatial divide. The walls are rendered as permeable boundaries.

In several scenes of Documenteur the composition of the shots makes use of windows as apertures and solid visible structures. When medium long shots present a view on and through a window in the foreground or the middle ground of the image, the composition creates a stark contrast between flatness and spatial depths. Windows define two contiguous spaces within the image. The shown wall delimits the visible deep space, and the window arranges a tightly framed view of moving bodies or the surrounding space. As a visible structure and a techné of visuality windows divide the space into an inside and an outside. As Anne Friedberg notes in her work on the window as a model in theories of painting, architecture, film, and screen media: ‘[t]he window opens onto a three-dimensional world beyond: it is a membrane where surface meets depth, where transparency meets its barrier. The window is also a frame, a proscenium: its edges hold a view in place’ (2006: 1). Given the long duration of takes from static camera positions in Documenteur, the tangible components of the architecture and the unchanging limited view of the camera are simultaneously brought to the fore for the film viewers. The unfolding images, which depict small gestures set against the immovable, built structures thin out the visible activities and variations in the shot. The film form thus constructs a sense of time and space, where the seemingly stilled moving images arrive at stasis or exhaustion.

Fig. 20: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 20: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 21: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 21: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

In Documenteur the cinematography probes the double capacity of windows as frames and as planes of visual representation. As frames, windows shown within shots centripetally draw the viewers’ attention to the limited visual appearance in the opening. As planes, windows seemingly flatten out the three-dimensional space, which lies behind the glass. As viewers, we sense the solid, transparent, and translucent materiality of glass panes as a shiny surface, which reflects light. Although we can look through the glass, we are aware of a barrier, which separates us from what is seen. In Documenteur the cinematography insists on this sense of disconnection and presents documentary images of everyday activities and scenes with the characters through shop windows. [3] Looking onto interior spaces with lively groups or solitary figures from the outside the film composes compelling images of self-exclusion and displacement.

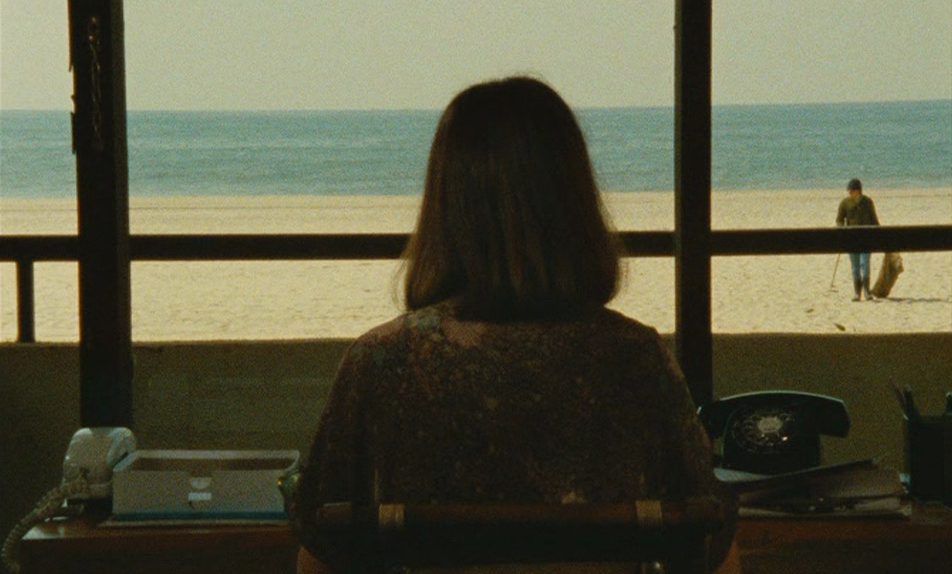

The most memorable scenes with a window as screen, holding a view, are set in an oceanfront house. Several scenes show Émilie’s work as a typist. She copies scripts for a filmmaker, who lives in the oceanfront house. Émilie is most often shown from the back as she sits at a desk in front of a large window with a view of the beach and the ocean. As viewers, we see what she sees, but we do not see her seeing. The figure, which turns its back on the viewers and the marvellous scenery in the distance evoke romantic landscape paintings. However, the sublime shimmers within limits. Like a raster or a cage, the framework of the window and the low balustrade of the house’s terrace obstruct the view of the scenery.

Fig. 22: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 22: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 23: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Fig. 23: © Screenshot from Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda, Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

Starting twenty-two minutes into the film, a scene presents a ‘reverse shot’ of this established locale and viewing position (22:00-23:32). In a medium close-up we see Émilie en face behind the window. In the shot her face is framed by two rectangular reflections. The sky, the ocean, and some sailing boats are mirrored within these opaque fields of light blue. When Émilie picks up the phone, the camera starts to move forward slowly and singles out her face. We overhear the soft and intimate phone conversation of Émilie and her friend. Both characters seem closely attached to one another. As viewers and listeners, we align ourselves with the emotional expressions and responses, which bind together the characters on the line. At the same time, a desolate sense of spatial separation is evoked when we see Émilie’s tears. The tears respond to her friend’s questions but can only be seen by us. The shot offers a contemplative look at Émilie’s face in close proximity. Yet, we are separated from the lonely character by the window’s glass. The cinematic scene, thus, intensifies the highly contradictory perceptions of being pulled in and being shut out, of being moved and being at a remove. The voices on the soundtrack, the visual complexity of the shot, and the fixed camera position, which cannot be attributed to a character’s gaze, propose an amalgamation of interior and outside, of presence and absence. The separation from the character behind the glass pane could be understood as an allegory for the film camera’s looking on—or looking out at—the world. Transparent and textured, the glass within the visual field doubles the glass of the camera’s lens. The imagery’s sense of separation and constriction evokes the peculiar absence and narrative agency of the camera, which by means of framing fragments, narrativises space as ‘seen’ and ‘scene’ (cf. Heath 1981: 37).

Conclusion

Varda’s site-specific film practice scrutinises the pictorial aspects, the indexical force, and the social inscriptions of the urban environment. In Documenteur the mise-en-scène seemingly results from a scrutiny of the immutable and dynamic aspects of given places and the improvised invention of possible routes and relations across space. The cinematography approaches the locations as test sites for reversing the hierarchy of foreground and background, of figure and surroundings, of intelligible shapes and empty spaces. Further, the images’ composition makes use of architectural components in order to modify gradually the arrangement of shapes, colours, contrasts, proportions, and textures within the frame over time.

In Documenteur the characters are predominantly shown in medium long shots. Insisting on significant relations between characters and the visible milieu, the narrative action contracts to the limited reach of characters’ gestures, which are bound to a place, captured in the frame, and come to a grinding halt within the duration of the take. Sedate tracking shots and long static shots register the duration of embodied acts and trajectories through space in real time. The long takes’ continuous display of movement slows down the visible changes that occur in the images. The camera thus becomes recognisable as a physical object that is placed. The camera’s slow pace or stasis overtly demonstrates that the frame is a structuring operation; a limited view on space that shapes a form. Tending toward stillness, Documenteur’s framed images seem to hold back the forward moving drive of narrative action. The images hold onto contemplative views of the opaque surfaces of solid constructions, transient material configurations, and bodies in motion or in repose.

As ‘An Emotion Picture’ Documenteur does not imply any direct communication between exterior appearances, embodied movement, sensory perception, and subjective moods or feelings. Sadness is not expressed by the alteration of objective and subjective images, nor by conventional patterns of montage, which punctuate the psychological drama in conversation scenes by shot reverse shot cutting. The cinematography refrains from imposing characters’ point-of-views on us as film viewers and only occasionally binds the spectators to acts of looking in the diegetic space. Thus, the film proposes a mode of nuanced reserve, which tends to eradicate the medium of film’s confidence in visual expressivity and affective sensation. In an interview Varda imagined a transposition of emotions from the visual realm and mimetic performances to the moving images temporal forms and rhythmic structures. Varda explains: ‘In Documenteur I tried something new which was to introduce a space-time of silence between moments of great emotion, to allow the audience the time to get there or to hear in themselves the aftershocks of the emotions displayed, the echo of the words, forgotten memories. It’s as though I wanted to use their own lived time in the film’s time. I propose emotion-filled moments, then images onto which these emotions can be transferred and then a silence in which the two can reverberate’ (2014: 113).

Documenteur foregrounds the materiality, the acts, and the duration of the film production for the viewers, because the unobtrusive camera inhabits the time and space of the urban environment. The imagery thus sustains a distinctive relation to the recorded contingencies of actual places and their everyday social life. As the film’s title suggests, the film links a documentary account to an untrue, fabricated story. Documenteur probes the limits of the narrative film form from within, as the forward-moving action intermittently comes to a hold and the diegetic space seemingly breaks down in incoherent intervals of images and unsettled impressions. Moving through moments of passivity and pure time the viewers might apprehend the protagonist’s grief and the film’s wandering in void spaces as forms of belonging.

Notes:

[1] Isle of California, LA Fine Arts Squad (Terry Schoonhoven, Victor Henderson, and Jim Frazin), 1971–1972, size: 42 × 65 ft., location: 1616 Butler Avenue, Los Angeles. http://www.lafineartssquad.com/isle-of-california/ (last accessed 19 September 2021).

[2] All quotes are taken from the soundtrack and subtitles of the DVD Mur Murs / Documenteur, Arte France Développement & Ciné-Tamaris Vidéo, 2012.

[3] The extended, observing views on display windows and shops invoke Varda’s 1974 film Daguerréotypes, which was also a collaboration with Aviv.

Acknowledgments

For permission to use screen captures of Documenteur, the author would like to thank Rosalie Varda-Demy and Ciné-Tamaris, Paris.

REFERENCES

Bénézet, Delphine (2014), The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, London & New York: Wallflower Press.

Deener, Andrew (2012), Venice: A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Friedberg, Anne (2006), The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Heath, Stephen (1981 [1976]), ‘Narrative Space,’ in Stephen Heath, Questions of Cinema, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 19-75.

Ince, Kate (2013), ‘Feminist Phenomenology and the Film World of Agnès Varda,’ Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Summer 2013), pp. 602-617.

James, David E. (2005), The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles, Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press.

Metz, Christian (2016 [1991]), Impersonal Enunciation, or the Place of Film. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mulvey, Laura (1975), ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ Screen, Vol. 16, No. 3 (October 1975), pp. 6-18.

Smith, Alison (1998), Agnès Varda, Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press.

Souriau, Étienne (1951), ‘La structure de l’univers filmique et le vocabulaire de la filmologie,’ Revue international de filmologie, No. 7–8, pp. 231–240.

Varda, Agnès (2012), ‘Agnès Varda et Emmanuelle Loyer parlent des 2 films’ (DVD bonus feature), Mur Murs / Documenteur, Arte France Développement & Ciné-Tamaris Vidéo, 2012.

Varda, Agnès (2014 [1982]), ‘Interview with Agnès Varda’ by Françoise Aude and Jean-Pierre Jeancolas, in T. Jefferson Kline (ed.), Agnès Varda: Interviews, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 108–117.

Song

The Doors (1967), ‘People Are Strange,’ Album: Strange Days, Elektra.

Films

Adjungierte Dislokationen (1973), dir. VALIE EXPORT.

Daguerréotypes (1974), dir. Agnès Varda.

Documenteur (1981), dir. Agnès Varda.

Fuses (1964–1967), dir. Carolee Schneemann.

Hotel Monterey (1972), dir. Chantal Akerman.

Moon’s Pool (1973), dir. Gunvor Nelson.

Penthesilea (1974), dir. Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen.

Riddles of the Sphinx (1976), dir. Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen.

Solidarity (1973), dir. Joyce Wieland.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey