Reflections on ‘Khadija Saye: ‘in this space we breathe’

by: Kadija Sesay & Marion Wallace , June 25, 2022

by: Kadija Sesay & Marion Wallace , June 25, 2022

Khadija Saye (1992–2017) was a British-Gambian artist of extraordinary promise. Her final series, ‘Dwelling: in this space we breathe’ is a set of nine photographic self-portraits that form an extraordinary, extended meditation on spirituality, trauma, and the body. Here, we reproduce all nine of the artworks in the series and, in slightly edited form, the labels that accompany them in the British Library exhibition, ‘Khadija Saye: in this space we breathe.’

Saye was tragically killed in the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017, at the age of just 24. Her mother, Mary Ajaoi Augustus Mendy, also died in the fire. At the time, Saye was exhibiting works in the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and was on the cusp of major success.

As curators of a British Library exhibition, we began to research this series in 2019. As we did so, we became increasingly entranced by the way in which the artist presents us with varied and multi-vocal points of reference. Constructed with a nod to the African photographic studios that flourished in the pre-digital age, the works provide layer upon layer of allusion to Gambian cultural heritage and spirituality, while engaging with modernity and popular culture, as well as introducing elements of subversion and the unexpected. By the time we opened the exhibition in December 2020, it seemed to us that every time we looked at the self-portraits, we caught a glimpse of something new and illuminating.

Prominent in these works are symbols of Khadija Saye’s Gambian heritage, most with spiritual significance. They reference both The Gambia, and religious faith, as sources of strength in the face of trauma—which, for Saye, included the experience of racism in Britain. As she wrote: ‘[i]n these questionable times we need positive imagery to push against the vile xenophobia and trash headlines!’ (Saye 2016)

The objects that the artist holds in these works suggest deep connections to indigenous religion, and to her Christian mother and Muslim father and their ancestors. We see Khadija Saye taking part in a healing ritual, for example, or displaying Muslim religious objects. The portraits radiate an inner power and—in some cases—peace, while continually challenging the viewer. In ‘Tééré’ (‘Amulet’), the artist wears a string of amulets across her eyes, thus taking objects that are normally kept hidden and making them intensely visible. In other works in the series, she foregrounds indigenous ritual practices that are often kept secret.

In matters of gender, too, Saye offers a twist to accepted practice. In ‘Kurus’ (‘Prayer beads’), she holds Muslim prayer beads; in The Gambia, it is normally men who are seen with such beads. Her attention to women’s experience is evident in ‘Andichurai’ (‘Incense pot’), the scent of this traditionally made clay pot very much associated with femininity and the home. But it is in ‘Limoŋ’ (‘Lemon’) that her gender politics emerge most explicitly. Lemons are used by women in The Gambia to clean and purify; but we suspect that their most important significance for Khadija Saye was their alignment with the title of Beyoncé’s famous 2016 album, Lemonade. The singer was a role model for Saye, and this work surely references Beyoncé’s construction, both hard-hitting and joyful, of a Black, matriarchal, historical world.

It is not only in the subjects of her works, but also through the process of their making, that Khadija Saye’s intentions as an artist emerge. For one thing, the artistic process encouraged her to think about gender politics. As she had written in relation to an earlier series, ‘I thought a lot about the traditional roles African women take within the male dominated space. The experience of role reversal took place when I physically was taking the lead and giving direction. There was a gentle negotiation of power and respect to produce an outcome to satisfy all’ (Cartledge 2020).

There was also the laborious photographic production process, ‘a ritual in itself,’ as Khadija Saye expressed it (n.d.). Wet collodion photography creates evocative, blurred, monochrome images. Khadija Saye took several shots of each pose which she printed onto metal as tintypes. ‘[In] making wet plate collodion tintypes,’ she wrote, ‘no image can be replicated and the final outcome is out of the creator’s control. Within this process, you surrender yourself to the unknown, similar to what is required by all spiritual higher powers: surrendering and sacrifice’ (Saye n.d.).

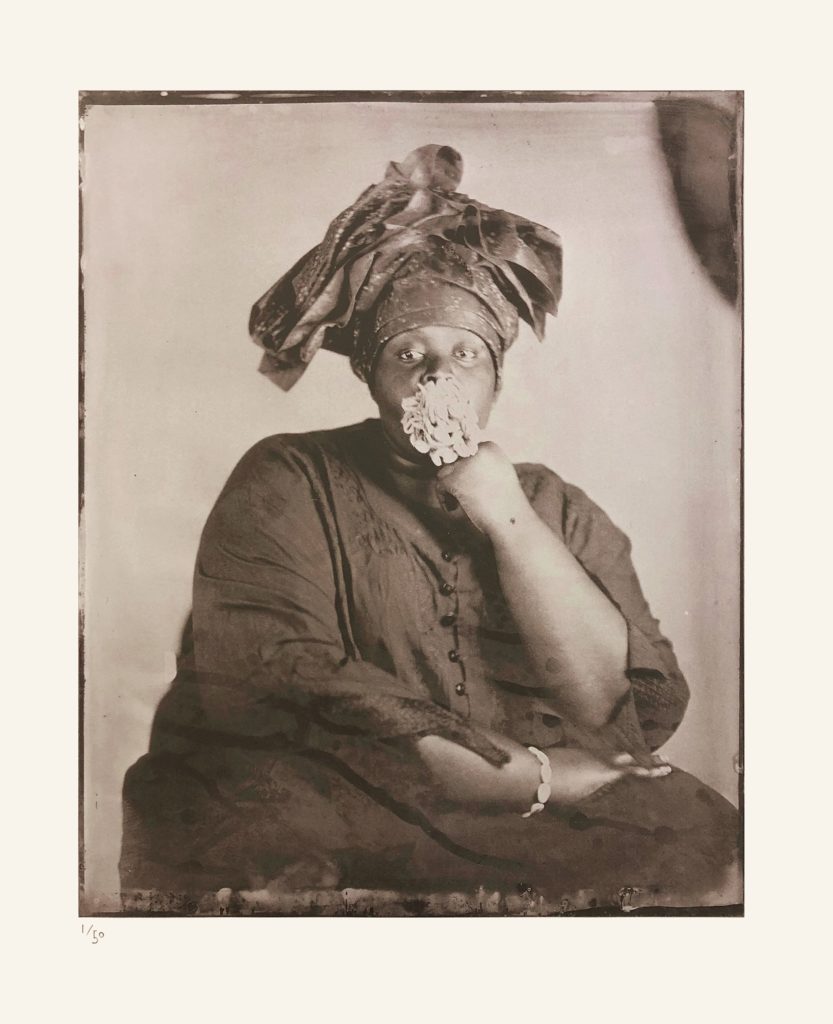

Khadija Saye’s works in this series seem to represent a deep well of strength in a patriarchal, racist world. Her decision to foreground herself—to make each image one of her own body—places an African woman centre-stage. No longer invisible, no longer anonymous, the subject of these pictures is a named female artist. And if the works continually reference trauma, with their subject drawing on healing and spiritual resources for strength, then they surely also indicate a form of triumph, as Khadija Saye immerses herself in African tradition, or looks defiantly at the camera, cowrie shells—that quintessential African symbol—held in her mouth.

This much we can be fairly sure of from our conversations with those who knew Khadija Saye and our research into Gambian culture. But some things in these images will always be a matter of conjecture. Why does the artist wear a black dress, an unusual choice for a young Gambian woman? What is the significance of the different headdresses she wears in each photograph? Why, in some of the images, are her eyes closed, or her mouth stopped?

If Khadija Saye had not been taken far too young by that terrible fire, she would probably have told us. The artist wrote and spoke about her work with great fluency: she wanted her meanings to be communicated. With her passing, a truly talented artist, on the verge of greatness, has been lost to The Gambia, the UK and the world.

In conclusion, we quote Khadija Saye’s own moving words on her legacy. ‘Whether it’s now or ten years down the line, I have this idea of opening doors–like previous artists of colour … I feel I have the potential to do the same’ (Venice Biennale 2017).

The Works

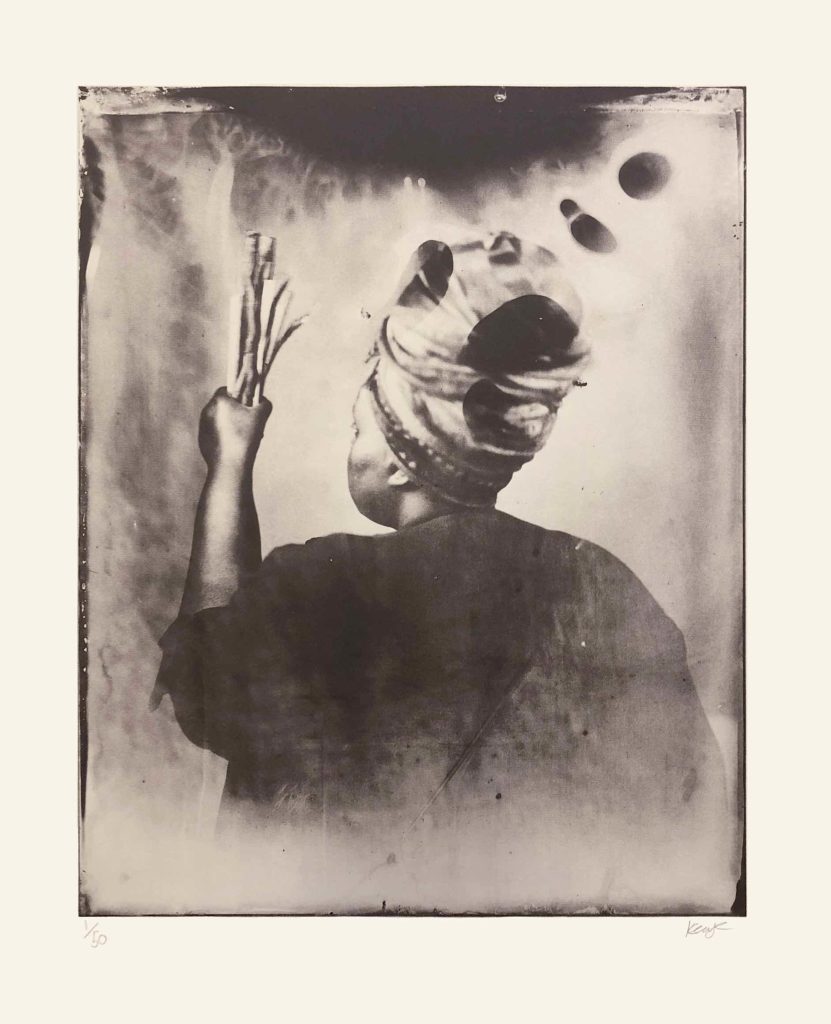

Saye photographs herself here with branches of the salvadora persica, the tree from which chewing-sticks, used as toothbrushes, are taken. These signify purification, as well as invocation of the spirits of the ancestors. She was introduced to indigenous ritual practices in The Gambia by her mother.

Sothiou was the first of six works in this series displayed by the artist in the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017.

The titles of the works in this series are in Wolof, a language of The Gambia and Senegal.

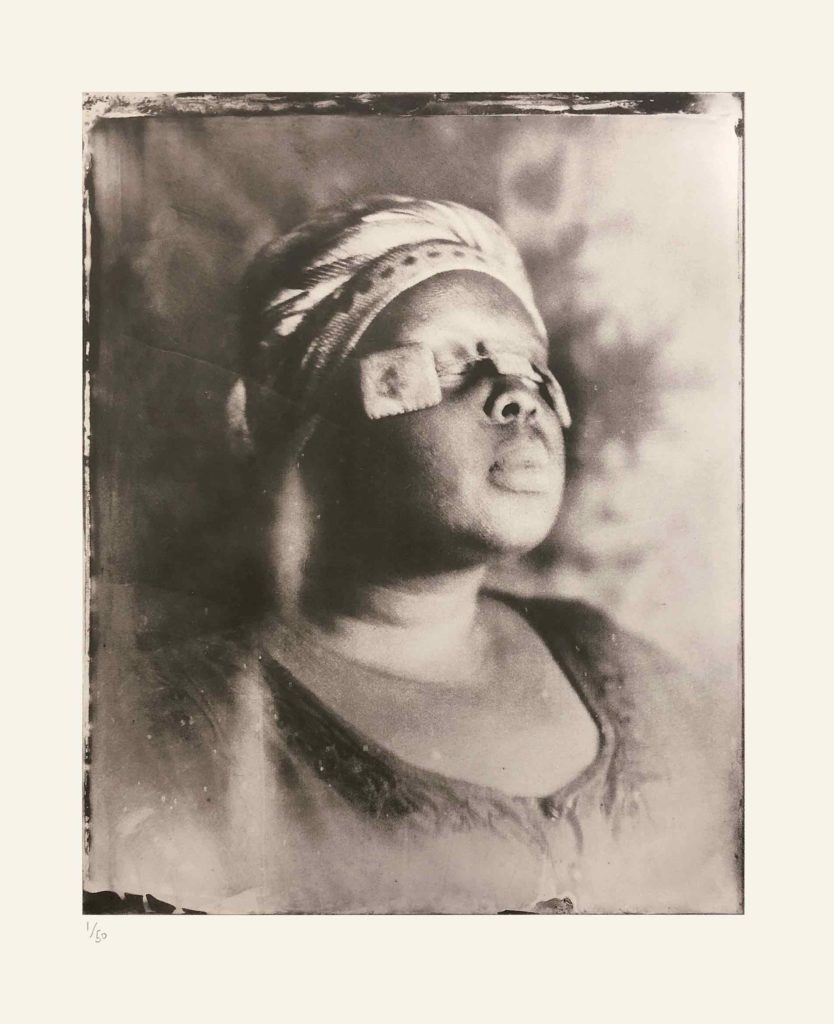

The string of protective amulets Saye uses in this image belonged to her father. Wearing amulets–words from the Qur’an written onto paper, here sewn into leather packets–is a common Islamic practice in Africa. In this work, Saye openly displays items usually concealed under clothing.

The artist’s pose and expression suggest a moment of prayer. Saye said that she created this series ‘from a personal need for spiritual grounding’ (n.d.).

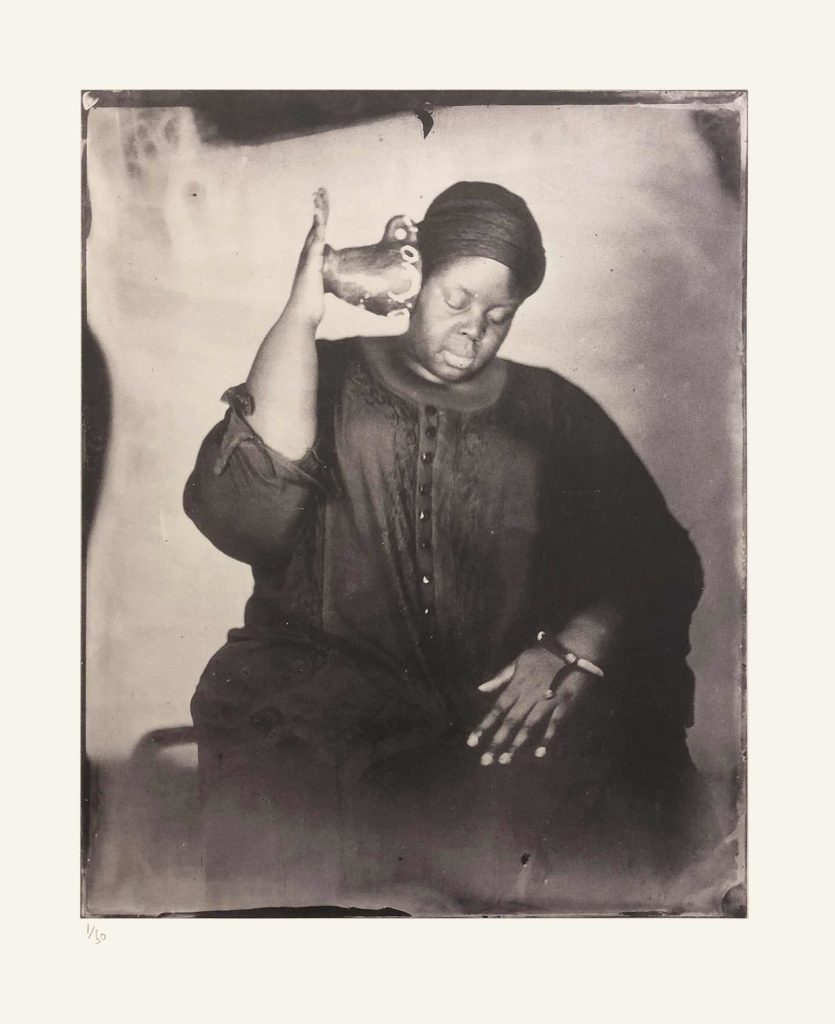

Saye holds a red clay pot with white decoration, made using techniques specific to the SeneGambia region. Universal in Gambian homes, the andi churai burns incense to drive away evil spirits in order to provide protection. In Gambian culture, the strong scent of the incense is closely associated with women and femininity.

In this surprising and ambiguous image, the artist holds a string of plastic lemons in her mouth. In The Gambia, the lemon is seen as a Western fruit, but it also implies cleansing the body and protection from evil spirits.

Saye may have intended a reference to Beyoncé, one of her role models, and her influential 2016 album Lemonade, with its historical vision of a liberated, Black, matriarchal society.

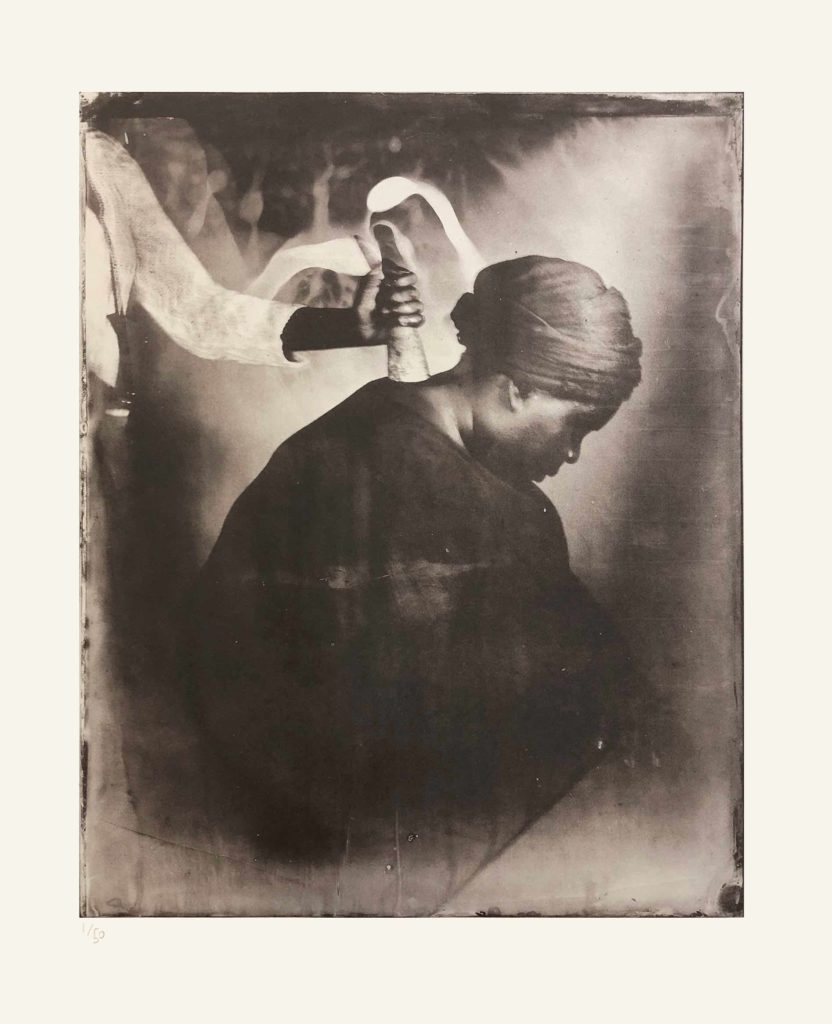

Gambian healers use cows’ horns in rituals to suck impurities from a person’s body. Cows’ horns are also associated with desolation and famine, when cows cannot survive. This work may speak of both trauma and healing.

The ‘healer’ in this image carries a small bag, perhaps containing medicinal equipment. The illusion of smoke from the horn may be a result of the wet collodion photographic process.

Khadija Saye wrote of the relationship between her art, the body and trauma: ‘We exist in the marriage of physical and spiritual remembrance. It’s in these spaces… [that] we identify with our physical and imagined bodies. Using myself as the subject, I felt it necessary to physically explore how trauma is embodied in the black experience’ (Saye n.d.).

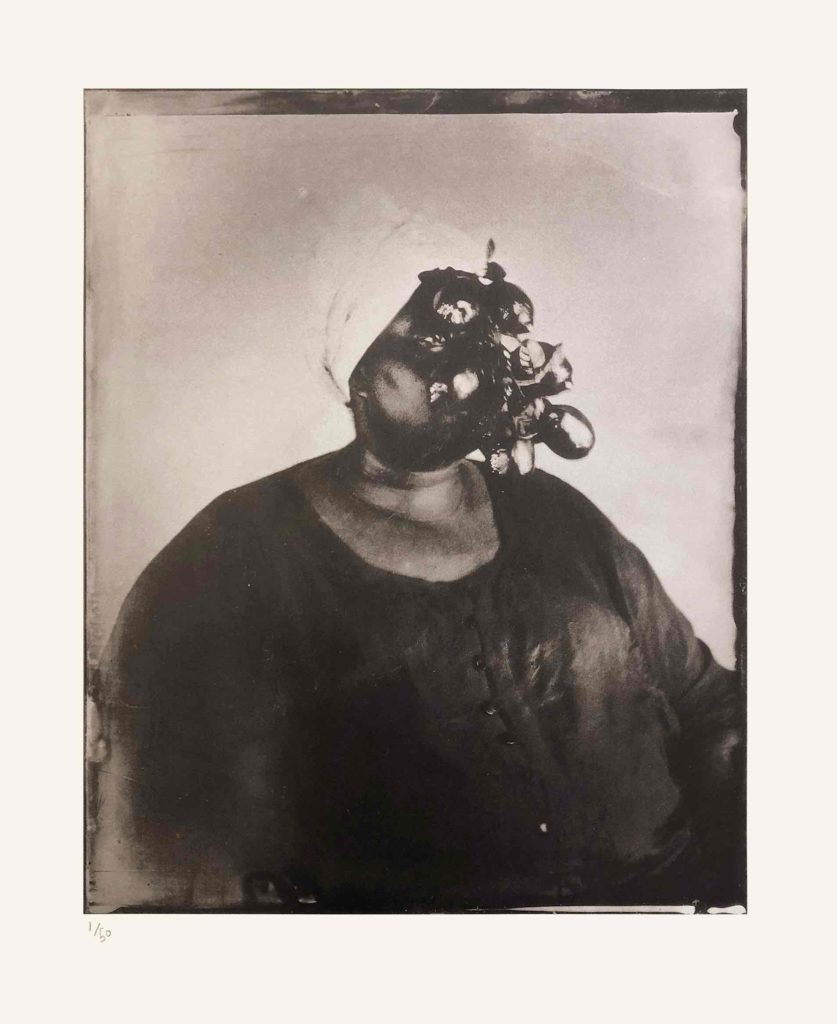

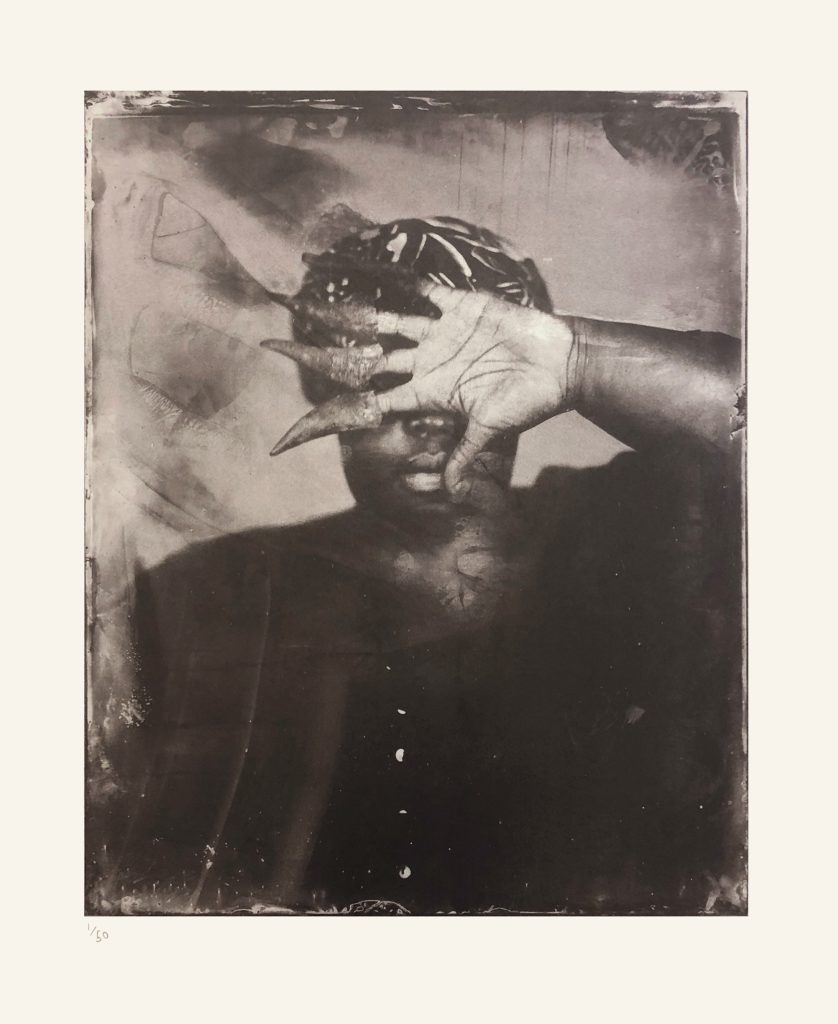

Saye wears goats’ horns on her fingers as she shields her face. These objects are used in divination, the process of discovering the reasons for life’s events and problems, and what can be done to change them. This image may suggest both fear of the future and the possibility of drawing on Gambian knowledge and spirituality to find a way through difficulties.

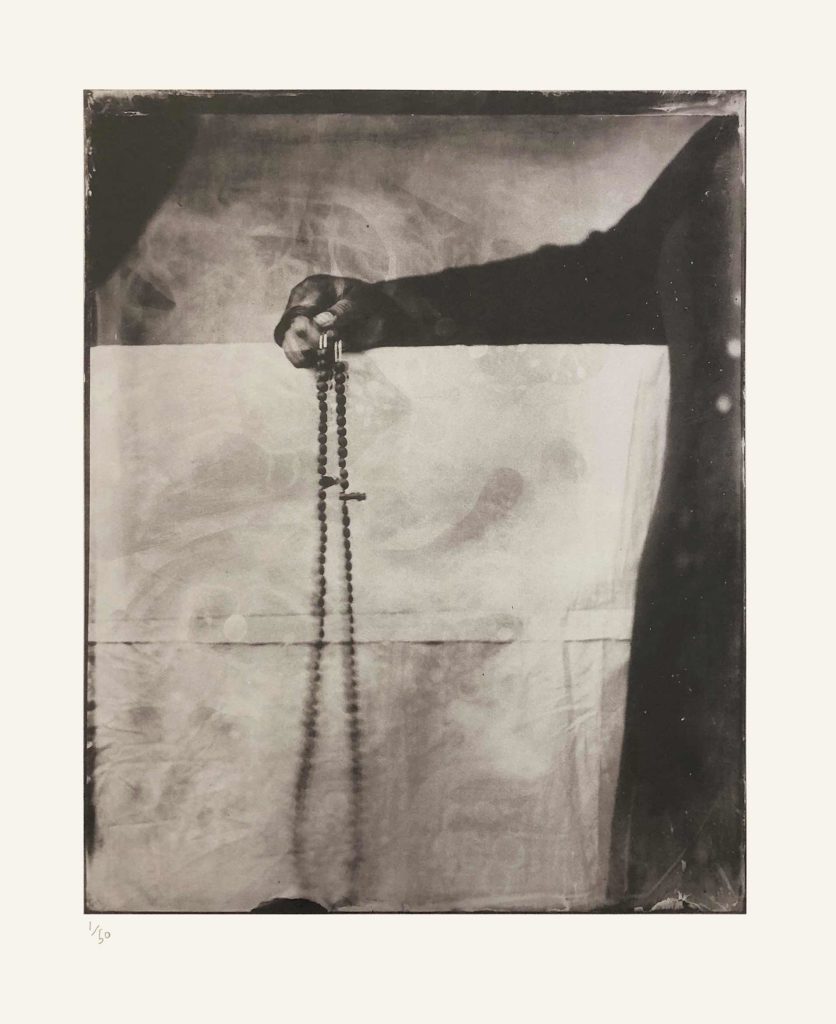

These Muslim prayer beads reference spiritual support in a time of difficulty. Prayer beads are also used by Christians. The mingling of Islam, Christianity, Rastafarianism and, in Saye’s words, ‘African spirituality’ is common in The Gambia (n.d.).

Women are not usually seen in public with Muslim prayer beads in The Gambia. In her work Saye subverts expectations around gender roles.

Saye holds a bunch of cowrie shells, strung together, in her mouth, and wears a cowrie-shell bracelet on her arm. In Gambian culture, her pose, supporting her chin on her hand, suggests unhappiness or discontent.

Used as currency for centuries, cowrie shells represent wealth and fertility and are used in divination as well as jewellery. For Africans in the diaspora, they symbolise connection with the continent.

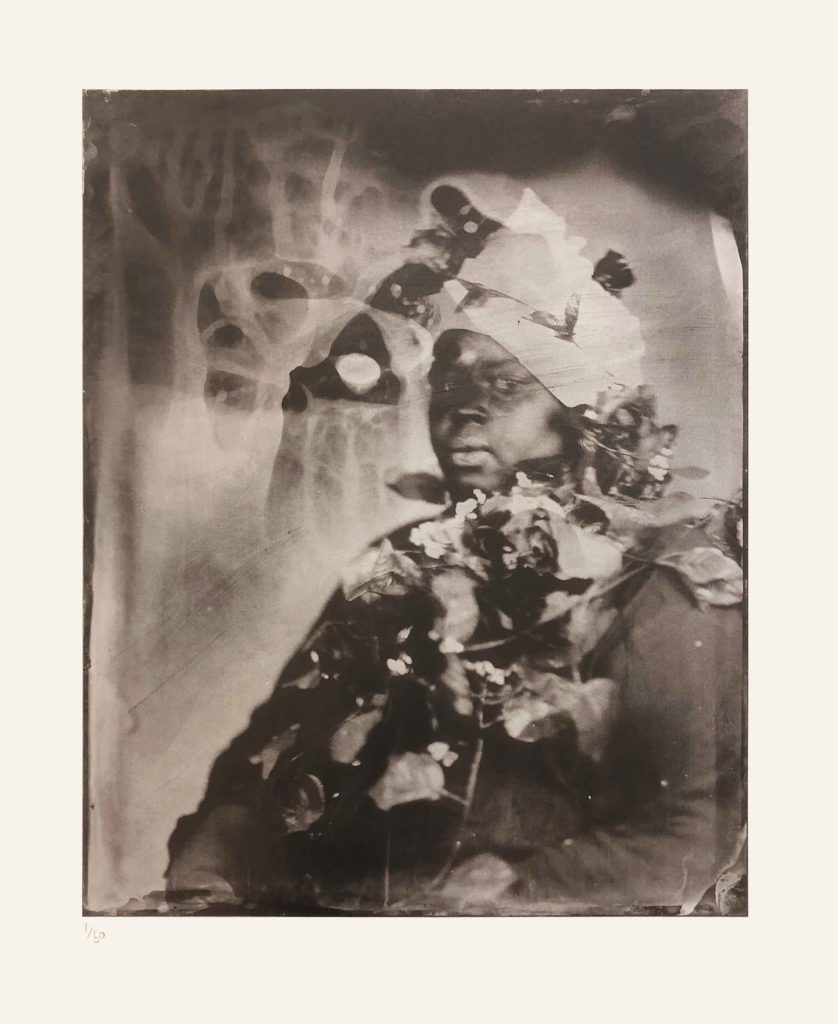

The artist has draped herself in strands of plastic flowers. These are often used to decorate homes in The Gambia, found on shrines, and worn by practitioners of indigenous medicine. The flowers may also link with Saye’s interest in popular culture, particularly her love of RuPaul, who plays with floral drag.

This work experiments with contrast and balance between her life in Britain and The Gambia, and between her personal and professional growth.

A Note on ‘Dwelling: in this space we breathe’ and the British Library Exhibition

Khadija Saye created these works by posing for a series of studio portraits. Using the wet collodion process, she printed the resulting photographs onto metal sheets, producing artworks known as tintypes, which were digitally scanned.

In the Grenfell fire of June 2017, many of the tintypes were destroyed, along with a suitcase containing some of the objects featured in the artworks. Six tintypes were, however, on display in the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale at the time. Earlier in 2017, Khadija Saye had worked with master printer Matthew Rich to produce Sothiou as a silkscreen print. The eight remaining silkscreen prints in this series were made after her death from the high-resolution digital scans.

It is the artist’s proofs of these prints, on loan from the estate of Khadija Saye, that were displayed in the British Library’s exhibition, ‘Khadija Saye: in this space we breathe’. The exhibition opened in December 2020, reopened on 18 May following the 2021 lockdown, and ran until 7 October 2021.

The tintype of ‘Peitaw’ was also included in the British Library’s major exhibition, Unfinished Business: The Fight for Women’s Rights (2021).

This article shows all nine works in the exhibition, together with a slightly modified version of the text that accompanied them.

For more on Khadija Saye and her art, watch this film. See also Khadija Saye: Cowries Incense and Amulets, a recording of a British Library event on 17 May 2021 and and this blog which references Sothiou.

The Khadija Saye Arts programme at IntoUniversity provides schoolchildren with visual arts experiences and education in her memory.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who made the exhibition at the British Library possible: The Estate of Khadija Saye, The Family of Khadija Saye, David Lammy, Nicola Green, Lucy Cartledge, Ana Freitas, Marloes Janson, Hassum Ceesay, Njok Malik Jeng, Victoria Miro, John Purcell Paper, Erica Bolton, Jealous, Almudena Romero, Christie’s and M.A.R.S., and British Library colleagues.

REFERENCES

Cartledge, Lucy, personal communication, 28 Feb 2020.

Saye, Khadija (2016), Instagram post, 16 Nov 2016 (last accessed 22 February 2022).

Saye, Khadija (n.d.), ‘in this space we breathe’, Catalogue of silk screen prints ([published posthumously]).

Venice Biennale: Britain’s New Voices (2017), dir. Alex Harding.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey