Notes on reading Riemke Ensing’s Watermarks or Gesturing Towards a Metamodern Self

by: Alexandra Dumitrescu , October 5, 2020

by: Alexandra Dumitrescu , October 5, 2020

‘I want the physicality of the book to create a physical message through the hands and the eyes that makes the reader more susceptible to the text.’

Claire Van Vliet

‘That whole underlying suggestive green colour throughout the book gives that wonderful sense of lichen and seaweed and light on water and has that amazing grainy feel of sand.’

Riemke Ensing

I work at a job where one is supposed to read every day, in order to keep up with what’s happening in contemporary literature (both domestic and international), and also to be able to gauge the value of a book based on a tweet, a Facebook or Goodreads pitch, a back flap blurb or a skimpy Amazon review. Besides, as an English teacher, I am expected to have read most, if not all, ‘significant’ books (contemporary or otherwise), and to have informed opinions about what is happening in the adjacent arts such as music, the performing arts, painting, or film. On top of these (perhaps mostly imagined) exigencies, I tell myself that I am supposed to be a homo metamodernus (Dumitrescu 2006), a whole, balanced, self-actualised human being.

However, the reality is that reading a book from cover to cover is a rare privilege. It occurs in the halcyon days of the school holidays when the term-time exhaustion has subsided and the pressures of preparing for a new term haven’t quite kicked in. Those are rare days of quiet in-betweenness, when I have rested enough to engage in activities more sophisticated than fleeting introspection, or furtively writing a poem between classes; vague gestures of care in the direction of my aspiring metamodern self (Dumitrescu 2014). I attempt, then, to do justice to the parts of myself, and of my world, that I have been neglecting for weeks. In the small window between the pressures of duties past and the anticipated pressure of duties yet to come, I remind myself that we are interconnected creatures (Dumitrescu 2007) and try to renew contact with my quasi-abandoned friends. Or I delve into the books that I have stacked during the term, books that I bought at literary events, or that friends were generous enough to send to me knowing how greedy I am for things of beauty that offer a fresh view on the mundane, artefacts that gesture towards a much-needed immanent transcendence, the spiritual in the material.

Riemke Ensing’s Watermarks, published by Claire Van Vliet at Janus Press (2019), is such a book. It simultaneously offers a new perspective on lived experience and a transcendence into a universe beyond the everyday of stress and strife, an opening towards the meta-modern. A world where things acquire meaning and are aesthetically pleasing. A meta-modern world (Nirmala Devi 1996) beyond the rat race that modernity has brought about.

Watermarks arrived in the mail during the last days of freedom of movement before the lockdown, when time to read and reflect seemed like a very remote possibility. Still, like a child who sneaks downstairs to peek at their presents early on Christmas morning, I could not resist the temptation of opening the book furtively between meetings, or when taking a break from marking. I would gently slip the almost-square book from its cardboard sleeve of a pleasing light ochre. Then, I’d run my fingers over the unusual texture of the cover that puts me in mind of raw, barely processed paper. I’d cast a passing glance at the paratextual details on the front flap, among which is the dedication to NZ print artist Beth Serjeant, one of the few Aucklanders who owns a collection of Janus Press books: rare, limited edition objets d’art, of which Watermarks is one. Van Vliet’s are precious books, often boxed, which gives the reader the feeling of being offered a gift that he or she needs to open and reveal.

Creating such an object is based on a series of artistic decisions, from the page size (24×25.5cms) to the paper texture (Barcham Green Renaissance 111) [1], the font type (Neue Hammer Unziale), and the illustrations. Letterpress printed by Andrew Miller-Brown, one can feel the words cast into the porous pages, smooth dark shapes on a field the colour of warm, cliff-coloured sand on a summer day.

The book enchants and offers opportunities for learning. I learn that a vitreograph is an etching on glass, in this case based on a photo taken by Van Vliet (who is The Janus Press, Vermont) while she was in New Zealand. Van Vliet’s vitreograph ‘The Reef of Muriwai’ (printed by Judith O’Rourke at her Littleton Studios) offers both a visual and tactile experience of the page, evocative of the flowing lines of waves, of their foamy crests, and of the texture of rocks covered in salt: dry, protuberant, sparse. Reading Watermarks, a limited edition, handcrafted book, is a rare privilege, an experience satisfying to all the senses. Of one hundred and twenty copies, I hold copy number 11, an objet d’art that warms the heart with its quiet glow.

In an interview for Radio NZ, Justin Gregory notes that ‘Janus Press in the United States has been turning out highly-designed, handmade editions that are more like sculptures than books. … They are complete art works in themselves.’ Beth Serjeant further extolls the materiality of the book: ‘The fact that you can touch it, you can hold it, you feel its weight, its texture. I love it. I love it’ (Gregory 2014). All books by Van Vliet are meticulously assembled, innovative and time consuming. The name of the Press itself is suggestive of the inspired, metamodern synthesis of invention and tradition that the process of creating these books involves. Janus, the Roman god who could simultaneously look forward and backward in time, suggests an equilibrium between tradition and experimentation.

Creating volumes anchored in tradition and seeking to delight while satisfying the exigencies of artists, craftspeople and collectors, Van Vliet has a special relationship to poetry and the art of the book, as she does to New Zealand itself. Alongside handcrafting poem collections by Seamus Heaney, Ted Hughes, and Denise Levertov, in 1982 she created a huge boxed book of Keri Hulme’s poems called The Silences Between (Moeraki Conversations). Van Vliet returned to NZ for conferences and book exhibitions, and repeatedly declared her love for these distant shores through her vitreographs, the photographs that she took, and the wonderful poetry collections that she crafted. That Van Vliet has turned her attention to Ensing’s poems is a privilege, one apt to motivate and inspire.

Van Vliet’s books celebrate writing by framing it in ways that reveal and enhance the experience of the text. They constitute special occasions that defy the triteness of mechanical reproduction that Walter Benjamin deplored as the mark of modernity (Benjamin 1969). The aggressiveness devoid of spiritual dimensions that mechanical reproduction often entails is challenged by Van Vliet’s affectionate crafting of books as art objects. Art, in a syncretic avatar as poetry combined with the visual art of vitreography and the craft of hand-making books, recaptures the spiritual dimension that announces the metamodern as an integrative paradigm of presence (Balm 2018).

This whole being, with all the senses and faculties such as memory and imagination, is present in Ensing’s Watermarks. The poem ‘At Muriwai,’ for instance, contains the texture of ‘rocks& stones,/ these elements of change’ that ‘unite us’ and allow for a ‘Memory’ that ‘takes flight/ Opens/ the clouds to small flashes of light where all the shadows speak/ and the bird is the poet singing in the wilderness’ (2019: 6). The implied smell and taste of sea, the dance of light and shadows, the sound of ‘mourning’, the subtle connection between the bird’s song and the poet’s art, all ensure the cohesion of a world where presence is as pregnant as absence, where the waves that ‘sweep in’ are as present as the longing for ‘something lonely, something lost’. The modernist poetics of absence and the postmodern fragmented self (Dumitrescu 2016: 216 & 183), seem to be mere memories for the metamodern self [2], since absence is accepted as presence by a persona who engages in a dialogue with the animate and inanimate aspects of nature, with the living and the dead, as she listens to the ‘call along the beach/ where the dead walk.’ The self is part of nature and discovers herself in her interactions with it, as well as in her exchanges with the past, which is seen not ironically, but as a realm that informs the present.

After I explore the paratextual details in the colophon, and promise myself to scrutinise them in more depth later, I delve into the poems. Even when pressed for time, I feel that I must read them at least twice, to offer a chance for their music and meanings to sink in. Each time I re-read them, I peel back yet another layer of meaning, another reason to enjoy the string of words. I wonder at the seemingly perfect accord between form and the content being expressed, at the promise of a universe where harmony and integration could describe reality.

Through line length and stanza structure, the words organise in patterns that evoke the movement of waves against the solid reality of the shore. Yet the concept of stanza seems to lose its meaning when it comes to Ensing’s poems. ‘Muriwai,’ for example, could be said to be composed of three stanzas, or just a single unit that ebbs and flows and knocks against the sand-like texture of the page. Lifting words from the poem and reproducing them (below) in typeset other than their original Neue Hammer Unziale—at once antiquated, elegant and somewhat timeless—seems blasphemous and irreverent. Ensing details the meticulous font choice:

The font itself … we discussed at some length. I wasn’t convinced at first, thinking it rather difficult to read, but gradually saw Van Vliet’s intent to bring something like a shimmer of light in water onto the page. It is almost as though the font replicated the waves, the lift and fall of water—the shape of the text.[3]

The font mediates ideas and feelings becoming fact. The content reflects both in and off the form of the poem, heightened and enlightened by it, in a dialogue renewed with each reading.

Spaces also play a part in the overall experience of the poems. There is a regularity about spaces, but no uniformity: as though while the beat of waves is somewhat predictable, no one wave is identical to another. In these poems that play with dynamics of presence and absence, position is as significant as the landscape is for the structure of a settlement. Note the difference between a prosaic set up in

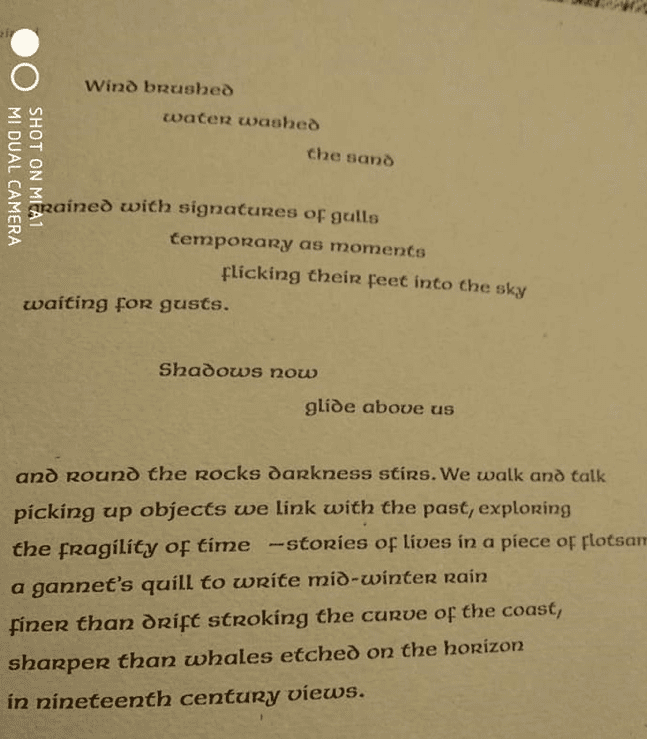

Wind brushed water washed the sand grained with signatures of gulls temporary as moments flicking their feet into the sky waiting for gusts. (Ensing 2019: 5)

and Ensing’s way of distributing the lines like parallel sets of steps below the title that evokes watermarks through its consistency and grey colour fill (see title photo above, lower left panel):

As waves would, each line starts close to where the preceding one has ended, each engendering the subsequent one in an accumulated momentum until they reach the shore together. From there a new adventure starts, that of seagulls as metaphors for the temporality of the sensible world.

The last seven lines above resemble a prose text; it is perhaps meant as a prose poem-within-a-poem, like the stories-within-stories in the Arabian Nights. The lines that start in the same place on the left hand side of the page, and only ever gesture towards the other end without reaching it, evoke the solidity of the shore, the terrestrial existence of the persona who meditates on the ephemerality of time, and the rugged continuity of waves. This serves as a fresh reminder of how form and meaning complement and reveal one another in this meditation on the human condition, poised midway between the lightness of the wind, the irregularity of the waves and the flight of birds in the first stanza, and the transparency of spirits and of gods in the last.

Like the poet who decodes for us the significance of ordinary objects through her poems, the persona reads the stories coiled in flotsam and takes in a world where the actual and the imagined slide into each other. A gannet’s quill recalls old writing practices, and is the pretext for a memorable implied metaphor (‘write mid-winter rain’) that slides into a sensuous anthropomorphic personification; drift is imagined as caressing the curved coast as one would a human being (Ensing 2019: 5). The parallelism ‘finer than…/ sharper than…’ anchors the temporary image in the permanence of the recorded past, trapping the ephemeral in the historical. Despite losing the fluidity of the moment, the transient now gains a layer of eternity.

Metaphor engenders metaphor telescopically, one arising from another, as seagulls are perceived as objective correlatives of the passing of the moments, and their flight a transience of shadows from the past. Punctuation is as important as line length and spaces: most lines are enjambed in ‘Muriwai,’ with sentences running from one line to the next without the encumbrance of punctuation, as if to underscore the fluidity of the movement of feelings. Three of the four endstopped lines belong to the prose poem in the middle, to the space where the persona contemplates, reflects and remembers, and where perceptions are more terrestrial, more grounded. The last line that ends with a punctuation mark, in this case a full stop, marks the end of the poem, which is suggestive of the subtle reaches of a world where ‘gods breathe the lifted wave into song.’ The integration, or existence side by side, of the material and the spiritual, mirroring one another, at once revealing and enhancing, evokes Luce Irigaray’s ‘immanent transcendence’ (30) and opens towards the metamodern as a paradigm of integration.

Watermarks plays with polysemy. The title could be an allusion to the faded writing or image within the texture of paper that could often signal aristocratic descent or business affiliations, or was simply the papermaker’s logo or symbol. Watermarks are also the traces left by water on sand, the discreet presence of spirits in the material world, the connection between the factual world and the spiritual one that becomes manifest through creativity.

Spirits wail and leave in the sand

A watermark. At the water’s edge

Gods breathe the lifted wave into song (Ensing 2019: 5).

This meditation on transience and time by a philosopher-poet reminds me of a story that I read growing up. Included in the Arabian Nights, it concerned a wise man who set out to write down all the accumulated wisdom of a lifetime. He wrote twelve volumes over several years, yet, dissatisfied with the outcome, he burnt them all and condensed all that he knew into one volume. This he also burnt. He then composed a single sentence that contained all his wisdom. That quintessential pronouncement might have been religious in nature; Ensing’s is poetic. It is the poems in Watermarks.

Notes

[1] The paper has been hand-produced by Bernie Vinzani and Katie MacGregor in their paper studios (Van Vliet 2019).

[2] In Towards a Metamodern Literature, the metamodern is defined as ‘a paradigm of integration of faculties (e.g. reason and emotions), systems of thought, different ontological levels’ (18), as well as a paradigm of becoming. See also Dumitrescu 2016.

[3] Private correspondence.

REFERENCES

Balm, Alexandra (2018), ‘An experience reading If Only by Riemke Ensing’, in Jack Ross (ed), Poetry NZ, 5 December 2018. https://poetrynzreview.blogspot.com/2018/12/riemke-ensing-if-only-2017.html (last accessed 8 June 2020).

Benjamin, Walter (1969), ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ in Hannah Arendt (ed.) and Harry Zohn (tr.), Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, New York: Schocken/Random House, 1969, https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm (last accessed 1 June 2020).

Dumitrescu, Alexandra (2006), ‘Foretelling Metamodernity: Realisation of the Self in the Rosary of Philosophers, William Blake’s Jerusalem and Andrei Codrescu’s Messiah‘, in De-Constructions of Identity, Adrian Radu (ed.), Cluj-Napoca: Napoca Star, 2006, pp. 151-168.

Dumitrescu, Alexandra (2017), ‘Interconnections in Blakean and Metamodern Space,’ in Barry Empson (ed.), Double Dialogues: On Space, Issue 7, Winter 2007, http://www.doubledialogues.com/article/interconnections-in-blakean-and-metamodern-space/(last accessed 4 June 2020).

Dumitrescu, Alexandra E. (2014), Towards a Metamodern Literature (PhD Thesis, University of Otago, March 2014), https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/4925 (last accessed 1 May 2020).

Dumitrescu, Alexandra E. (2016), ‘What is Metamodernism and Why Bother Meditations on Metamodernism as a Period Term and as a Mode,’ in Dave Ciccoricco (ed.), What [in the World] Was Postmodernism?, Special Issue of Electronic Book Review, 4 December 2016, https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/what-is-metamodernism-and-why-bother-meditations-on-metamodernism-as-a-period-term-and-as-a-mode/ (last accessed 1 May 2020).

Ensing, Riemke (2019), Watermarks, Vermont: Janus Press.

Gregory, Justin (2014), ‘Janus Press: The New Zealand Connection,’ Standing Room Only, 21 September 2014, https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/standing-room-only/audio/20150491/janus-press-the-new-zealand-connection (last accessed 4 June 2020).

Irigaray, Luce (2005), An Ethics of Sexual Difference, Carolyn Burke and Gillian C. Gill (tr.), New York & London: Continuum.

Nirmala Devi, Shri Mataji (1996), Meta Modern Era, Pune: Computex Graphics.

Van Vliet, Claire (2019), ‘Thoughts on Bookmaking,’ Poets House, 10 October 2019, https://poetshouse.org/thoughts-on-bookmaking-by-claire-van-vliet-of-the-janus-press/ (last accessed 31 May 2020).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey