JARring: Making PhEmaterialist Research Practices Matter

by: Emma Renold & Jessica Ringrose , May 16, 2019

by: Emma Renold & Jessica Ringrose , May 16, 2019

Introducing phEmaterialism: Feminist Posthuman and New Materialist Research Methodologies in Education

‘PhEmaterialism’ (Feminist Posthuman and New Materialisms in Education) started out as the Twitter hashtag in 2015 for the network conference, Feminist Posthuman New Materialism: Research Methodologies in Education: ‘Capturing Affect’ (Ringrose, Renold, Hickey-Moody & Osgood 2015). However, it rapidly became a concept-making-event; a living, lively ever-expanding human and more-than-human working group, which now brings together a globally dispersed collective of students, researchers, and artists experimenting with how posthuman and new materialism theories form, in-form and reassemble educational research (Ringrose, Warfield & Zarabadi 2018). PhEmaterialism combines feminist posthumanism (Haraway 2008 & 2016; Braidotti 2013; Åsberg & Braidotti 2018) and the new materialisms (Barad 2007; van der Tuin 2016). Its abbreviation foregrounds the entanglement of educational scholars interested in working with new feminist materialist and posthuman ideas and practices. The ‘ph’ is pronounced ‘f’, so that sound and letter formation bring posthuman and feminism together in one expression.

Posthuman theorisations decentre ‘mankind’ exceptionalism–organised via the privileging of white, individual, rational, European masculinity, repositioning humans as part of, rather than sovereign over, a vibrant ecology of active matter (Bennett 2010; Braidotti, 2013; Chen 2013; Haraway 2016). Critical posthumanism rejects racialised, sexualised, and gendered exclusions from humanity and prioritises indigenous and other forms of marginalised knowledge and meaning-making (Weheliye 2014; Tallbear 2015). Posthuman performativity revalues the agential power of non-human actors, objects and things (Barad 2003 & 2007). PhEmaterialist researchers stick to and are stuck with (Ahmed 2017) the explicitly pheminist orientation of post-phallic posthumanism and new materialisms (Braidotti 2013; Renold et al. 2018); and find this approach generative for creating queer kin (Halberstam 2016; Haraway 2016). Insistent that we cannot lose the momentum of critique conjoined with an affirmative politics of change, the posthuman feminist asks: what are the possibilities for injecting humanist empiricism (Braidotti 2013) with radical extensions through our discursive-material research apparatus (Barad 2007)? Indeed, Karen Barad’s rethinking of the relationship between ethics, knowing and doing, her mashed up ethico-onto-epistemology (Geerts 2016), and, therefore, her remattering of causality and action, through the concept of ‘intra-action’ has been pivotal in these moves for empirical researchers. Barad encourages us not to conceive of change as happening to or from something. Rather, she invites us instead to consider how meaning is always in process, always mattering and always unknown because ‘with each intra-action, the manifold of entangled relations is reconfigured’ (Barad 2007: 393-394). As she suggests, ‘there are no singular causes. And there are no individual agents of change. Responsibility, and the ability to respond to what matters ‘is not ours alone’ (Barad 2007: 394).

Educational scholars have seized upon these post-foundational moves to knowing and becoming and the challenges they present for dominant and normative social science research methodologies (Coleman & Ringrose 2013; Taylor & Ivinson, 2013; Taylor & Hughes, 2016; Ringrose, Warfield & Zarabadi 2018). Related to the ‘post-qualitative’ turn (Lather & St. Pierre 2013) in educational research we find yet another reworking and disrupting of the ruins of scientific objectivity and neutrality (MacLure 2011 & 2015; St. Pierre 2013; Gallagher 2018) that radically questions the making and valuing of empirical ‘data’ (Lenz-Taguchi & Palmer 2013; Koro-Ljungberg 2015) by mapping the relationality between human and more-than-human bodies, affects, objects, sounds, discourses, digital and earthy landscapes—as a whole range of im/material forces (Pederson & Pini, 2016, commonworlds.net).

By fundamentally re-questioning what constitutes educational ‘data’ (Lenz-Taguchi & Palmer 2013; St. Pierre 2013) and what data can ‘do’ (Coleman & Ringrose 2013: 2), social science research methodologies are becoming increasingly and necessarily expansive. Arts-informed practices, in particular, are engaging and shaking up the research process from design to ‘dissemination’ in novel ways with new affective currencies. PhEmaterialist researchers are becoming much more crafty in making research matter through creative and mobile methodologies that can offer potential new ways of ‘doing something with the something doing’ (Manning & Massumi 2014) via a range of edu-activisms which are mining the politics of matter in educational/community engagement and queer-feminist public pedagogy (e.g. Hickey Moody 2015 & 2017; Hickey-Moody, Palmer & Sayers 2016; Harris & Taylor 2016; Springgay & Zaliwska 2016; Renold 2018 & 2019; Gray, Knight & Blaise 2018; Denzin & Giardina 2018; Gallagher & Jacobson 2018; Renold & Ivinson forthcoming).

As queer and feminist research-activist scholars, our particular aim has been creating ethico-political research methodologies that might re-animate the regulations and ruptures of how gender and sexuality mediate children and young people’s lives in schools and beyond (Fox & Alldred, 2017; Allen & Rasmussen 2017; Osgood & Robinson 2018; Ringrose et al. 2018; Davies 2018; Quinliven 2018; Hodgins forthcoming). Key to this is actively seeking out ways to connect more directly with how our feminist and queer research practices operate at the thresholds of ‘research’ ‘public pedagogy’ and ‘activism’—what we sometimes refer to as the ‘more-than’ of research when communicating what we do in more conventional social science research forums and spaces (Renold 2018, 2019). This has involved interrogating how what we do comes to matter across the diverse assemblages we become entangled with, from the micro-political to local and national macro-political terrains (Ringrose & Renold 2014). Inspired by the ‘intra’ness of entangled im/material forces that take our research-activisms on unplanned routes, we have begun to theorise these encounters as ‘intra-activist research assemblages’ (Renold & Ringrose 2017). Joining Barad’s ‘intra’ with ‘activism’ signals the ways change and transformation are always in process, always unpredictable and always a matter of entanglement (the ‘intra’ of intra-activism) in explicitly political ways (shifting ‘action’ to ‘activism’). And it is the making and framing of these intra-activist research assemblages and our approach to the concept of affect as ‘politically oriented from the get go’ (Massumi 2015: viii) that brings us to the heART of the matter in this paper. We emphasise ART here to foreground how JARring emerges out of the phEmaterialism arts-based, participatory research field of inquiry and intervention into the live political ecology of education (Hickey-Moody 2017; Renold 2018; Renold & Ivinson forthcoming). Erin Manning’s notion of an old medieval definition of art as ‘the way’ has inspired and helped us theorise this process. Manning argues that to conceive of art as the manner through how we engage, helps us glimpse ‘a feeling forth of new potential’ (2016: 47). We have learned how this requires careful attention to the proto-possibilities of ideas as they roll, flow and are transformed through artefacts and events.

Massumi argues that ‘art is about constructing artefacts—crafted facts of experience. The fact of the matter is that experiential potentials are brought to evolutionary expression’ (2013: 57). Since its inception, the jarring methodology has become a process of ‘immanent critique’ (Manning & Massumi 2015) that makes the ‘facts of the matter’ in our research-activist assemblages visible to a wider social science community. We have theorised this process as the making and mattering of da(r)ta and da(r)taphacts (Renold 2018). Inspired by Massumi’s quote ‘artefact’, da(r)ta (arts informed data) has become a working concept for the process of using art-ful practices to craft and communicate experience in our research-activisms, such as the making of the ‘gender jars’. Da(r)taphacts are the art-ful posthuman objects that generate a quality of what Deleuze calls, ‘extra-beingness’. Detached from the environment they are created in, da(r)taphacts mobilise a more-than-human politics as they carry affects and feelings of this crafted experience into new places and spaces. Mixing data with art to form the hybrid da(r)ta is an explicit intervention to trouble what counts as social science data and to foreground not only the value of creative methodologies but also the speculative impact of art-ful practices (Renold 2019). As phEmaterialist practice, the ‘ph’ replaces ‘f’ in da(r)taphact, to register and treasure the posthuman forces of art-ful objects as potential political enunciators and to encourage a move away from fixed, knowable and measureable social science facts (Holmes 2015). The ‘act’ in da(r)taphacts signals our explicit ethico-political activist intentions.

We begin with the story of a troubling government-funded project on ‘Young people’s experiences of gender’ (Renold, Bragg, Jackson & Ringrose 2017) that experimented with inventive phEmaterialist methodologies in the hope that they might augment our ‘ability to respond’ and stay with the ‘gender trouble’ (Butler 1990; Haraway 2016). We undertook the consultancy as an act of what Massumi refers to as ‘processual duplicity’(2017), responding to a standard research tender with a research design that had the potential to get crafty with the neo-liberal university ‘research impact agenda’ (Laing, Mazzoli-Smith & Todd 2017). One of the pARTicipatory methods that kick-started a series of unanticipated twists and turns in the research was the use of small glass jars, sticky notes and ‘sharpies’ (permanent marker pens) introduced at the end of friendship group interviews in schools. We were experimenting with how jar as a discursive expressive verb intra-acted with the physical object of a small glass jar. The jar became an explicitly activist invitation to decorate and fill with messages anything that communicated how gender mattered to young people (this method is contextualised further below).

In the following section we share how lively, disorienting and experimental post-qualitative phEmaterialist research can be/come, from the intra-actions in the original ‘fieldwork’ and the unanticipated spin-offs that fielded the potential of what more a jar can do when our research ‘findings’ on how gender matters to young people became troubling and we became troublesome in our refusal for this research to be ignored, silenced and contained. JAR became an entangled discursive-affective-matter-realising force of what affirmative ethico-aesthetic phematerialist practice feels and does.

More than a Jar: An Emergent Gender Jarring Methodology

‘We, as a species, have crafted jars … for a distinct purpose in response to distinct real-world problems … the jar becomes more than just a jar’ (Koro-Ljungberg & Barko 2012: 258-259).

Fig. 1

In 2015 we were part of a research team commissioned by the Children’s Commissioner Office for England to study how gender came to matter to the everyday lives of just over 125 children and young people living in four contrasting locales across England (Bragg, Renold, Ringrose & Jackson 2018). The advertised tender for this government-funded research enabled us to craft a research design that allowed us to be open and upfront throughout the process about the team’s feminist, queer and participatory and rights-based approach (Leavy & Harris 2018). Central here was our ethico-political aim to create research encounters with and for young people in school environments that might go some way to enable us to explore the regulatory and rupturing effects of how gender matters in flow, and offering as many different ‘ethical moments’ for ‘becoming participants’ (Renold, Holland, Ross & Hillman 2008) enabling young people to tune out or withdraw from an activity or moment, without necessarily having to articulate this desire explicitly. The project was supported by a youth feminist advisory group (Newid-ffem)—a group Emma had been facilitating for a couple of years in a local Welsh secondary school. Together, and building on and contributing to a history of crafting socially engaged arts based research methodology (Wang, Coomans, Siegesmund & Hannes 2017; Leavy 2017) we eventually created a multi-phased progressive process that allowed for different modes of expression to surface through a range of da(r)ta making methods including talk, drawing, mapping, photo-elicitation and image sharing (e.g. memes/ FB profiles) over a two hour period with small friendship group interviews (see Renold et al. 2017 for full overview of the different tasks and methods).

The first hour opened with visual-discursive prompts that invited general talk on names, clothes, bodies, popular culture and their interaction with human and non-human others in different spaces and places, and times, including sharing moments ‘scrolled back’ from their mobile phones (Robards & Lincoln 2017). The second hour introduced activities explicitly focusing on gender as a conceptual and onto-epistemological category—for example, as gender identity and gender stereotypes; and other act/ivisms, including, gender-related acts of violence and gender-justice and equity activisms. To enable discussion of the much under-researched focus on children and young people’s views on representations of transgender, non-binary gender, gender fluidity, genderqueer and agender identities and expressions (see Gilbert & Sinclair-Palm 2018; Bragg et al. 2018) we introduced a series of images of high profile transgender, non-binary and feminist activists, including media celebrities. Matter-realising Judith Butler’s enduringly germane ‘gender trouble’, this second hour was pivotal in exploring how young people were navigating an increasingly visible ‘gender revolution’ (National Geographic 2016) in local peer cultures and day to day lives more widely.

The final da(r)ta task was the ‘jarring’ activity, which directly invited young people to consider in any way they wanted, how ‘gender jars’. The fifteen-minute activity invited each young person in the group to enter into a more private and activist space by generating their own messages for change and in ways that could be directed at the funder or more generally to a wider public. The materials on offer for each participant included one glass jar, with a screw-top mirror lid; a selection of multi-coloured ‘sharpies’ (a popular, coveted brand of permanent marker pens); and small pieces of paper in the shape of speech bubbles. They were invited to be as creative as they liked and could write on the jar, in the jar, using words, pictures, symbols etc. With their permission, our aim was to illuminate the jars with battery powered tea-lights, messages still inside, and assemble them, as da(r)taphacts, at the launch of the completed research for others to intra-act with, to touch and be touched, and maybe jolted into action by young people’s messages for change.

While we were especially keen to experiment with how the word-thought jar might intra-act with the physical object jar as a communicative vessel that historically has played its part as a carrier of difficult to control and contain substances and objects (see Koro-Ljungberg & Barko 2012), it is important to re-emphasize how the gender jarring activity took shape and form, as the final task. The session progressively built up to the gender jarring activity through a series of creative practices, so that by the time the jars were introduced they were already lively with an immanent and affective micro-politicality that was intra-acting with the d(a)rta and talk earlier in the session. Thus, how the associations of ‘jar’ as unsettling, destabilising, vibrating and jolting might matter-realise ‘to pressurise the process of thought-expression’ (Massumi 2018: 130) was occurring in a specific ‘time-space-mattering moment’ (Barad 2007). Moreover, while the jars were introduced specifically as potential da(r)taphacts in the making (that is, as potential carriers for change), they offered multiple possibilities for mapping jarring affects in the d(a)rta making session itself. For many young people, as we illustrate briefly below, difficult to articulate feelings that may have been thought-felt in the session, now had a dedicated outlet, and could be ‘contained’ in a psychosocial dynamic through the process of writing, inserting and sealing them in the glass jars. We explore these matterings through two jarring vignettes below.

Making Da(r)ta and Da(r)taphacts with (How) Gender Jars

‘We perceive-with objects … participating the relations they call forth … creating the potential for future relations’ (Manning 2009: 81).

Fig. 2

The jarring activity became a collective process which offered multiple d(a)rta-making and mattering possibilities (Fig. 2). For some, the jar seemed to become a container for what could not be voiced in the session, with some young people, spending the allotted time silently scribbling and stuffing messages inside, at a steady or furious pace. Others decorated only the outside of the jar, with abstract colours and shapes. For example, one older young person (age seventeen) drew fragmented gender symbols, explicitly stating that they wanted their jar to show how they hate being labelled, categorised, consumed or contained. Subverting the task entirely, one group created an additional jar which they turned into a gift for the researcher to express how affirming the session had been for them. In this section, we share two short jarring vignettes: jarring queer-kin and jarring schizoid-femininity. Taking inspiration from Braidotti’s ‘alternative figurations’ (2002), each vignette has been carefully crafted to provide readers with a partial glimpse, through word and image, at how the jarring method intra-acted inside the full session and a hint at how the jars became lively more-than-human pARTicipants, calling forth relations that gesture to the complex process of how gender is mattering in the lives of young people.

Jarring queer-kin

We meet Lou (age 13, white British) with her two ‘BFF’s’ (best friends forever) Cherie and Allan at an academy school on the outskirts of London. In the first naming activity, we learn about Lou’s fraught relationship to their birth name Jamie-Lou, an experience which is reiterated and expanded on several times throughout the interview. Lou describes how her primary school peers used to constantly ‘take the piss out of’ having a ‘country singer’ style name and how ambiguous ‘girl’ (Jamie) and ‘boy’ (Lou) signifiers fuelled a lot of gender-based bullying. By year 6 (age 10) Lou used he/him pronouns and became Louis on the school register. Louis then became Jamie-Lou in secondary school and is known as ‘Lou’, using she/her pronouns. Lou describes her gender identity at age 13 as ‘in-between girl and boy’ and a ‘tomboy’. She talks at length about having to negotiate unwanted and painful family pressures, from her mum and sister, in particular, to act ‘feminine’ and ‘become a girl’. Indeed, Butler’s ‘hegemonic heterosexual matrix’ (2004) is in full swing as the whole group describe being ‘hassled all the time’ for not conforming to the gender and sexual norms that regulate who and how they can be in school. Over the course of the session, there are multiple stories of how Lou’s best-friendships with Allan (from primary school) and Cherie (in secondary school), have been transformative in shifting their feelings of being ‘outcasts’ at school, at home and in various public places and spaces. Using the interview to tell stories of how their group has expanded over time to embrace other ‘outcasts’, what emerges in our two-hour session, is a supportive human and more-than-human matrix of shared be/longings and doings.

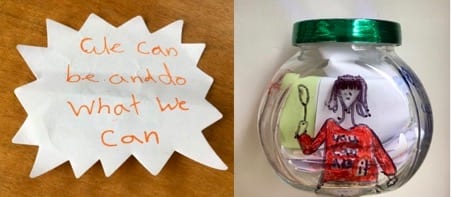

When the jar is introduced, it seems to matter-realise the affective qualities of these embodied intimacies in unique and interesting ways. On one side of Lou’s jar, in blue marker pen, are two human stick-figures holding two balloons each with the numbers 12 and 13 located inside each balloon outline. Underneath each stick figure is a lone balloon unanchored and free-floating. On the opposite side, a large colourful character (Fig. 3) wearing trousers, and a bold red T-shirt with the slogan, ‘you can do it’ grips a small balloon. On the remaining sides are names; Jamie-Lou in large red font and on the adjacent side, the four first names of Lou’s closest ‘BFFs’. Significantly, it is the only jar from the entire collection that scribes individual friends’ names or the name of the maker.

Fig. 3

Inside the jar, Lou has written as separate messages on the sticky notes, statements of collective hopes and desires (transcribed below in random order retrieved for writing this section):

‘People should be treated the same as other’

‘No uniform.’

‘We can be what we want.’

‘People with problem should not be treated different.’

‘You should not judge people for what their name is.’

‘We can be and do what we can.’

In the group interview, Lou, Cherie and Allan articulate a shared strong belief that ‘when you get older … everyone just accepts who you are and what you do’. Indeed, each message in Lou’s Jar seems to carry this potentiality, demanding a more accepting future for identity formation and recognition. Rupturing the rules and regulations of how gender has mattered/is mattering each statement offers a series of ‘cans’ and ‘shoulds’ for how gender might one day emerge as problem-free, and where difference can thrive in a non-judgemental, equitable world. The only definitive statement, without the precursor of a ‘should’ or ‘can’ is, ‘no uniform’—an enduring theme in our school-based research that surfaced racialised, classed, gendered and sexualised discourses of discomfort, fear and shame (Renold et al. 2017). With Lou’s hopes and dreams for a more equitable world sealed up inside her jar, the jar’s outsides get personal with an already happening un/contained ‘can do it’ assemblage of named t(w)een BFFs and balloons.

Jack Halberstam argues how gender-queerness convokes ‘different ways of being in relation to others, different notions of occupying space’ (2016: 369). Underscoring the importance of ‘friendship networks… when assessing structures of intimacy’, this queer sensibility, Jack suggests, offers an ‘altered relation to seeing and being seen’. Lou’s jar in its making and mattering beyond the fieldwork site appears to give form-force to this complex entanglement of intra-personal and political dreams and declarations, permanently making the belongings of how the ‘I’ (Jamie-Lou) and ‘we’ (BFFs) of identity matter with marker pens. And with each turning of the jar, the namings meet (party? memory?) balloons, marked with age categories (12/13), which are held by and seem to affectively hold each human figure–balloons filled with t(w)eenage dreams, hopes, fears and desires which could be released at any time, with one already on the loose. This emergent, fragile, proto-celebratory queer-kin jarring convokes the potential and limits of ‘can-do’ trans-individuality—that ‘we can only be and do what we can’.

Jarring schizoid femininities

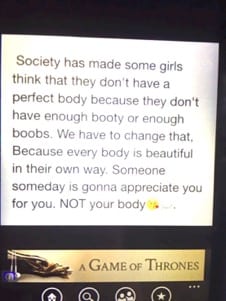

Shanice (age thirteen) is one of the only Jamaican young people in her school year, which is predominantly ethnically white. She talks animatedly about her extended family who live in South London, and social media has become an important avenue to be social and stay in regular connection with her family and friends beyond school. Shanice is active on Ask.FM, Instagram, WhatsApp and Snapchat. She draws upon Ask.FM memes during the interview to exemplify or expand on issues that different members of the group raise. For example, when her friend, Jani, brings up the relentless pressures on girls to post ‘pretty’ images online, she shares this meme (Fig. 4) and it intra-acts with the talk to spark a discussion around the tension between wanting to be seen as beautiful, but resisting acting on this desire for fear of being judged as ‘attention seeking’.

Fig. 4

In the interview, Shanice briefly draws attention to the racialised dynamics of performing schizoid femininity, in this case multiple, contradictory, competing elements of idealised femininity such as keeping up one’s appearance but not being openly vain or competitive (see Renold & Ringrose 2011). She states that ‘every boy like, if you’re too dark you get like cussed for that. But then if you’re light you get like, yeah, yeah, but then boys start saying, oh light skins are too … oh no, I need a girl with curly hair, and it’s really annoying … but in their eyes, they don’t really care about your personality.’ Shanice describes how certain Instagram posts have helped her to stop ‘crying’ about some boys’ comments (Fig. 5):

Fig. 5

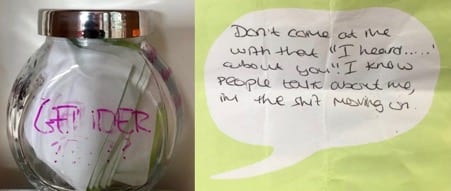

Shanice’s frustration over contradictory and unfair standards facing Black girls, in particular, intensifies in the jarring task. On the outside of the jar, three sides, make personal and affirmative body-beautiful-me statements, couched in well-worn neo-liberal discourse of Dove-confidence (see https://www.dove.com/uk/dove-self-esteem-project.html): BEAUTY (in blue): I’m me, and beautiful (in pink) and Love yourself be you xx (in black). On the fourth side, a series of five question marks underscore the word GENDER (in pink) that opens up a more uncertain and curious jarring of how gender matters, the contradictions of which become more acute inside the jar.

Indeed, each note is populated with da(r)ta that seems to dramatise a battle between society’s contradictory rules of black girlhood and her own life (Fig. 6)—messages which intra-act with inspirational slogans that are taken directly from social media memes and pedagogical statements about what ‘sket’ means.

Fig. 6

‘You’re so full of yourself’ No I had a lot of insecurities and low self-esteem which I worked extremely hard to overcome and now I realise that I’m awesome and I don’t care if you think otherwise.

Society has made some girls think that they don’t have a perfect body because they don’t have enough booty or boobs. We have to change that because everybody is beautiful in their own way. Someone, somebody is going to appreciate you not your body (love heart symbol).

YOUR BEAUTIFUL

I believe everybody should be feminist.

How can you suck man’s dick, but be scared to eat in front of him?.

Don’t come at me with that ‘ I heard…. about you’. I know people talk about me, I’m the shit moving on.

Sket: Someone who sleeps around and is just a general whore. Always bitchy to everyone and mostly mean. You could also compare it with a slag.

In fifteen minutes, Shanice creates a da(r)taphact that as you reach in and pull out the messages (a process that is different each time) transports you into a dynamic micro-political schizo assemblage that powerfully confronts society’s in your face, ‘come at me’ schizoid femininity; where body and self are both separated and together (‘somebody is going to appreciate you not your body’); where feelings of insecurity, shame, agency and empowerment entangle with a compulsory ‘I don’t care’, ‘I’m awesome’ attitude; where ‘Sket’ is carefully defined, with a knowing and owning that offers potential for resignification (see similar practices in the reclaiming of ‘slut’ in Ringrose and Renold 2012). Is this a da(r)taphact of or for ‘immanent critique’ (Manning & Massumi 2015)? Has Shanice’s jar, if only in the moment of its making, become a means to matter-realise ‘the shit moving on’ from the oppressive, schizoid constraints of hierarchical, racialised, sexualised, abject and yet expected and rewarded femininity?

While the Jarring task took off, in ways that we hope we have been able to share albeit briefly above, what we did not anticipate at the time was how the facts of the matterings that surfaced through the methods used to generate d(a)rta created with young people would jolt and affect in ways too troublesome to be supported by the funder (the details of which cannot be made public). To this day those 100+ jars remain under lock and key, preserving, like a jar can, stored, in waiting, to intra-act in future art-ful encounters. The messages, in digital form at least, have reached the wider world through our published research report (Renold, Bragg, Jackson & Ringrose 2017), but we continue to grapple with the uncanny nature of the jar to both contain and convoke. Carefully attending to the complexities regarding the political capacities of d(a)rta in each research assemblage is a critical aspect of researcher response-ability and an integral part of phematerialist ethical practice.

What Jar’s You?: Co-creating PhEmaterialism Resources and Events with Young People

‘It’s always good to make space for the unpredictable. Sometimes the most exciting things happen when you least expect them’ (Renold 2016: 69)

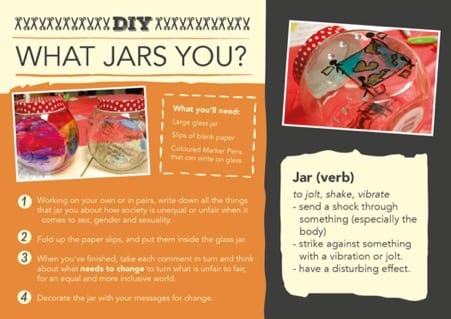

Affects, write Massumi, can be fascist and violent, blocking and disabling – but there is always movement. As Erin Manning writes about, in her notion of art as ‘the way’, as process, rather than form or object, while these jars maybe stuck in form, their process has evolved, and the jar phEmaterialist practice continues to in-form our practice. The feeling-force of the jarring activity generated such evocative and provocative da(r)ta that Emma re-routed and returned the methodology, and its activist potential back to Wales, inserting and integrating it into a radical resource that was unfolding and rising at speed. In stark contrast to England, physical and political proximity to policy and practice making assemblages in Wales (relationships forged and founded upon years of carefully cultivated collaborations) enabled new openings to take this activist potential of the jarring methodology on its way. Following the royal assent of the potentially ground-breaking Violence Against Women, Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence Act (VAWDASV 2015) Wales was buzzing with promise and possibility. As the Gender Matters project was forcibly coming to a halt, Emma facilitated the stARTer project (Safe To Act, Right To Engage and Raise) with an advisory group of 12 young people across urban, coastal and semi-rural localities in Wales. Their first activity to share what mattered to them was the jarring activity, and six months later this was designed to become one of the central activities in the 75-page activist resource ‘AGENDA: A young people’s guide to making positive relationships matter’ (Renold 2016) in What Jars You? (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7

Co-created with young people, AGENDA is an interactive online feminist activist tool-kit with the sole aim to support young people, age eleven to eighteen, to speak out about and get involved in local and global social, cultural and digital change-making practices on gender-based and sexual violence – issues that are all too often silenced, undermined, sensationalised, simplified or pathologised. Inspired by the Latin, ‘things to be done’, ‘matters to be acted upon’, AGENDA is an affirmative, ethical-political and creative approach to engage and change deeply entrenched and complex issues. It is phEmaterialism in action, jam-packed with over 30 creative change-making ideas sourced from local and global youth activist stories, with da(r)taphacts made, found or hyper-linked to. Indeed, so many of the issues addressed in the resource, including the gender pay gap, misogynoir, poverty, mental health, street harassment and LGBTQI rights, are areas that the young people from the Gender Matters project were inserting into their gender jars as matters of concern. Crucially, then, AGENDA was creating an opening for the jarring to continue to jolt in an explicitly activist resource that was laying the foundations for how else gender-based and sexual violence can be addressed with young people. And young people’s da(r)taphacts were jarring the way (see the making of the ruler-skirt, Renold 2018). Indeed, AGENDA takes the jarring methodology and disperses its potential throughout the resource because it is all about creating art-ful encounters that make space for young people to learn and speak up about gender-based and sexual violence through the micro-political practices of others. It also includes a section, highly relevant to this paper, called ‘tackling the dream-busters’. This was something that the young advisory group were particularly keen on including, knowing how difficult and risky raising awareness on these issues can be and not just in their own peer groups and online. As we were all too painfully aware, the dream-busters are also adult others who struggle or refuse to hear, support or act upon ‘what matters’ once they have surfaced.

Anchored with sponsorship from Welsh Government and multi-agency support, and enhanced by the global ripples of the #metoo movement, AGENDA’s affirmative approach to risky, radical and overtly political content has flourished. Schools in Wales, and increasingly in England, are reaching out for support, and AGENDA (accompanied by our outreach team[1]) is finding ways to become response-able, sharing what’s possible in each context and space. The What Jars You? activity also seems to have become one of the most popular and affective in the entire resource. It captures everything about the material-affective-discursive qualities of how to step into the art-ful ness of micro-political activisms. Indeed, da(r)taphacts co-created with young people at the launch of AGENDA have become use-ful, intra-active pedagogical and ethical objects. Over 40 young people attended a morning of pre-launch AGENDA workshops which included being invited to take part in the What Jars You? starter activity. In thirty minutes they filled their jars with da(r)ta and two volunteers, carrying the jars in wooden trays with the words ‘what jars us’, ‘fragile’, ‘making change matter’ (Fig. 8). As the seventy five policymakers and practitioners arrived to register, they were each gifted a jar.

Fig. 8

The aim was for the jars to affect those who ostensibly hold decision-making powers and to connect them to the ever-widening gulf of young people’s experiences through objects, da(r)taphacts, explicitly created through and for political change.

We have experimented with this process on many other occasions since, and each time we are crafting an ‘event’ which offers an ‘immanent critique’ through new processes and products, which in the instance of the AGENDA launch was about trusting in how the jars, as da(r)taphact might take on a quality of ‘extra-beingness’, transporting ideas and experiences for others to intra-act with, and in ways that kept personal identities anonymous. Creating distance from the personal and individual through the collective gifting was vital (given the backlash that outing what matters to you on these issues can incite), and the jars had the capacity to do this, to hold these potential revolutionary affects—to yield an ‘extra-beingness’. In fact, because conference delegates knew that the jars had been created that morning for them by the young people who were still physically in the room, the way they connected directly to felt experience (their affectively quality) seemed to take on an extra-charge—intensifying their extra-personal, transindividual vitality.

Landing tentatively but always in a field of possibility, we have seen the impact of the AGENDA jars take-off. In many ways, the jarring methodology has become a minor gestural force (Manning 2016), drawing out ‘the potential at the heart of a process’, through ‘force imbued material’ that is making itself felt across a range of carefully cultivated events, as da(r)ta and d/artphacts that participate in professional and public pedagogy, including in our higher education classrooms (Ringrose et al. 2018; see Braidotti et al. 2018). Indeed, they have also been igniting a series of research activisms in primary and secondary schools across Wales and beyond, registering, disrupting and propelling ‘what matters’ forward and in some cases re-assembling the rules, jolting and connecting the rawness of young people’s troubles and rage with each other, and with practitioners, teachers, social workers, youth workers, police officers and government ministers, from the south Wales valleys to New York, in a panel with the first minister for Wales, sharing innovative ways to advance gender equality.

And with each site visit new da(r)taphacts are made to matter, and with permission, they are gifted and shared to in-form future pedagogy, practice or policy from the micro to the macro. The latest iteration has involved working with teachers in 10 primary, secondary and special schools who are inviting students to use the jarring methodology to make da(r)ta and craft da(r)taphact to inform and share the schools’ development of their relationships and sexuality education with governors, parents/carers, and other schools across Wales. This is part of a creative new approach to making Relationships and Sexuality Education matter in ways that foreground children and young people’s voice, rights and experience. A living phematerialist curriculum for schools is vibrating with potential (see Renold & McGeeney 2017b) and the jars are in-forming this work.

#Impact Jars and Image-i-nation: Digital Intra-activisms In-forming Policy, Practice and Prizes

Further capacity for the jars ‘extrabeingness’ to vibrate, unsettle and connect across networked political publics, was exploited through activating a digital phEmaterialist presence in the policy focused Twittersphere of the UK Equalities Select Committee Inquiry into young people’s experiences of sexual harassment and violence in schools. While vital in its potential to surface an area long neglected and territorialised by the individualising binary logic of anti-bullying discourses, with their victim-perpetrator subject positions and obfuscation of the complex ways in which young people turn on each other to shame hurt and abuse (Schott & SØndergaard 2014), this inquiry really did jar with us. For too long, children and young people’s experience of sexual harassment in schools has long been on the funded and un-funded research radar and research agendas of feminist academic educational scholars, whose papers, reports and books for well over two decades have consistently mapped out these experiences but are too often neglected by policymakers. Here was yet another inquiry calling for evidence, and we were enraged that academic research evidence never seems to matter enough in and of itself to create the ‘force-feeling’ (Manning 2016) to effect change. The jars called us into action, again!

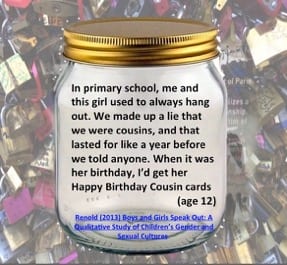

This time, we got creative with the digital onto-power of the jars. For 30 days leading up to the consultation, we put quotes from our English and Welsh-based research on sexual harassment (Ringrose, Gill, Livingstone & Harvey; Renold 2013) inside a digital image of a jar (Fig. 9), with the ironic hashtag, #researchmatters ( Fig. 10) and tweeted each image to the Women and Equalities select committee.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

This image-i-native intervention was to draw attention, not only to the digitised jar da(r)taphact highlighting, through papers and direct verbatim quotes what children and young people endure in school, it was also signalling what jars the research community when research evidence struggles to matter and prod policy and practice into action. As faithful, multi-tasking scholars, we submitted evidence in the traditional format through our ‘evidence’ reports, but it was the digital jars that captured the committee’s attention. Two days after tweeting the jars, we were both invited to act as informal consultants in shaping the inquiry, thus opening up rare and crucial spaces to augment the digital intra-activism by connecting the inquiry lead facilitator with a wider assemblage of gender jarring colleagues engaged in feminist research on this issue.

Three years on, we have been harnessing the haptic visuality (Marks & Polan 2000) of the jars as digital da(r)taphacts as still and moving images across policy and practice terrains—images which convoke sensations of touch and movement through looking and which have been created for children at public engagement events to intra-act directly with (Fig. 10).

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Much of this digital mattering has been occurring in Wales, a country with a rich history of social justice and equalities agendas and risings, and a devolved government with a distinct policy context where the ‘margins of manoeuvrability’ (Massumi 2015) are operating in a relational field where revolutionary potential has been more able to ‘amplify and bloom’ (see Renold 2019). Most notably this mattering has occurred in the crafting of the Welsh Government document, ‘The future of the sex and relationships education curriculum in Wales’. Here, a colour image of a line of jars back-dropped by a South Wales valleys landscape is the first image that greets the reader on opening the document. It was created by ten-year-olds in an extended version of the jar activity in a project, ‘Crafting Equality: Stitching our Rights’ which involved selecting and placing coloured buttons that connected to the feelings of living in an unjust world in a jar (Fig. 12, Renold & McGeeney 2017a: 2):

Fig. 12

This image, among other digital da(r)taphacts now semiotically intra-acts with the recommendations for a radical new vision of relationships and sexuality education in Wales, making young people’s voices matter and JAR in a process which had limited capacity to meaningfully consult with children and young people.

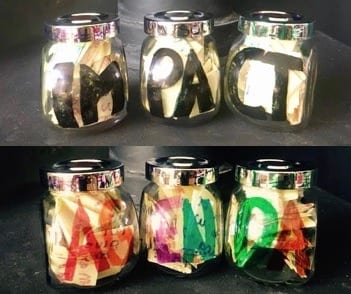

Moreover, in an unexpected twisted ‘turn’ of events, the AGENDA resource and the JARS return, ironically making their mark in an official institutional space on the theme of ‘research impact’ during Emma’s interview for the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) outstanding ‘impact on society’ prize for her work on pARTicipaotry approaches to creative activisms with young people via the phEmaterialist AGENDA resource. Co-producing the film with the film-maker, she shared the story through a series of da(r)taphacts. Making the process force-felt, prior to the interview, four core members of the school-based feminist WAM (we are more) who formed immediately following the AGENDA launch created ‘IMPACT AGENDA’ jars. As the interview drew to a close Emma gifted the jars to the panel, brim-ful with messages of how the resource and their own agendas have made a difference to their lives and the lives of others (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13

Transindividual, non-representational, more-than-human, in this gifting moment, these ethical-political da(r)taphact were making the politicality of researcher-response-ability force-felt and mattering (Barad 2007). And if you look closely at the promotional/celebratory film (https://esrc.ukri.org/news-events-and-publications/impact-case-studies/transforming-relationships-and-sexuality-education/) you can spot the original Gender Matters jars, temporarily released from their locked cupboard, making a cameo appearance, to signal how sometimes research can fly and sometimes it can fold, but phEmaterialist research will always jar, and will always be on the turn.

Conclusion: ‘On the Turn’, Jarring the Future

‘To make a situation important consists in intensifying the sense of the possible that it holds in itself and that insists in it, through struggles and claims for another way of making it exist’ (Debaise & Stengers 2017: 19).

In her book, Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed (2017) writes about being routinely wound-up by others when they are confronted with feminist killjoys. Feminist killjoys, she continues, who call out the problem, tend to become the problem. They JAR. We JAR. For us, engaging with the generative affective qualities of our jarring methodology we have been experimenting with a process that we feel is beginning to capture the ways in which phEmaterialist research practices are productively working with becoming more-than the problem. Indeed, the driving force in writing this paper for this special issue has been to provide a partial cartography through words and image, how lively, disorienting and experimental the mattering of our JARRING practices have be/come since they first surfaced as a da(r)ta making activity in the Gender Matters project. Our story joins other projects and practices that are beginning to share and theorise how post qualitative phematerialist encounters are coming to matter beyond the academy.

Jayne Osgood and Kerry Robinson write in their final chapter from ‘feminists researching gendered childhoods’ that ‘do this work requires a logic of unknowability, a logic of openness, and a logic of uncertainty’ (2018: 177). Perhaps, in the telling, when time-space contracts to produce the illusion of coherence, it has come across as a knowable and linear process, as one colleague reported at a recent event, ‘I love your jar project’. Rather, JAR is simultaneously the discursive-affective-matter-realising forces that when stilled and prised apart, begins to capture what a collective, affirmative, response-able ethics can feel and do. It began with how what we do matters, and string-figure-like continued and continues to matter in expected and unexpected ways.

Our research intra-activisms are rooted in Debaise and Stengers notion of ‘speculative pragmatism’ – doings that are always already ‘on the turn’ (a seventeenth-century definition of jar) in ways that help us stay ‘open to the insistence of the possibles, and of the pragmatic, as the art of response-ability’ (2017: 19). In and across each section we have attempted to map how our jarring practices have insisted on generating what matters, inside carefully crafted encounters, events and resources, that have, in different ways, contributed to in-form policy, practice and pedagogy in our field of inquiry. These craftings and graftings have required ‘passion and action, holding still and moving, anchoring and launching’ (Haraway 2016: 10). And while temporary exists and departures (some voluntary, some forced) have always been part of the process amidst the foldings and perishings of moments and projects, new hopes and possibilities have sometimes emerged and flourished.

Returning to the sensory and affective intensities of JARring, we bring this article to a close with the 1520s definition of jar, which is ‘bird-screeching’! When we became aware of this variation in jars’ etymological history, we instantly began likening our troublesome jarring methodologies and research activisms to Guattari’s writings on the messenger bird. In a section on ‘existential refrains’, Guattari introduces the metaphor of the messenger bird ‘ that taps on the window with its beak, so as to announce the existence of other virtual Universes’ (2013 [1989]: 147), that is, other ways of being that might rupture the status quo. This statement conjured an image in our minds-eye—its haptic-visuality resonating with our jarring ways of how what we do comes to matter. Sometimes in our participatory research with young gender and sexual becomings and activisms, our research-activist beaks gently tap away at the status quo, and sometimes we become, Sara Ahmed’s hammer-smashing, calling out the violence of how gender and sexuality jars. Sometimes we become screeching sirens, creating research activist assemblages that support those who want to express their experiences, but at a distance, or hidden from view entirely. Silent, screeching and anywhere in between, we are always entangled as part of our PhEmatieralist approach in the more-than of what we become part of, and our emergent jarring methodology is diffractively pARTicipating in this process. It has allowed us to think through and matter-realise the transversal journey of how addressing gender and sexuality in children and young people’s lives continues to vibrate, shake-up, unsettle and jolt (Osgood & Robinson 2018). And, amidst all the uncertainty, we have little doubt that it will continue to be productively JARring.

Notes

[1] The core team includes Matthew Abraham, Victoria Edwards, and Kate Marston.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living a Feminist Life, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Allen, Louisa & Mary Lou Rasmussen (eds) (2017), The Palgrave Handbook of Sexuality Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Åsberg, Cecilia & Rosi Braidotti (2018), A Feminist Companion to the Posthumanities, Amsterdam: Springer.

Barad, Karen (2007), Meeting the Universe Halfway, Durham: Duke University Press.

Bennett, Jane (2010), Vibrant Matter, Durham: Duke University Press.

Bragg, Sara, Emma Renold, Jessica Ringrose and Carolyn Jackson (2018), ‘More than Boy, Girl, Male, Female’: Exploring Young People’s Views on Gender Diversity within and beyond School Contexts’, Sex Education, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 420-434.

Braidotti, Rosi (2002), Metamorphoses: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Braidotti, Rosi (2011), Nomadic Subjects, New York: Columbia University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi (2013), The Posthuman, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Braidotti, Rosi & Maria Hlavajova (eds) (2018), Posthuman Glossary, New York: Bloomsbury.

Braidotti, Rosi, Vivienne Bozalek, Tamara Shefer and Michalinos Zembylas (eds) (2018), Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, London: Bloomsbury.

Chen, Mel E. (2012), Animacies, Durham: Duke University Press.

Davies, Bronwyn (2018), ‘Ethics and the New Materialism: A Brief Genealogy of the ‘Post’ Philosophies in the Social Sciences’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 113-127.

Deleuze, Giles & Felix Guattari (1987), A Thousand Plateaus, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Denzin, Norman, K. & Michael D. Giardina (2018), ‘Introduction’, in Qualitative Inquiry in the Public Sphere, London: Routledge, pp. 9-22.

Fox, Nick & Pam Alldred (2014), ‘New Materialist Social Inquiry: Designs, Methods and the Research-assemblage’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 399–414.

Gallagher, Kathleen (ed.) (2018), The Methodological Dilemma Revisited: Creative, Critical and Collaborative Approaches to Qualitative Research for a New Era, London: Routledge.

Gallagher, Kathleen & Kelsey Jacobson (2018), ‘Beyond Mimesis to an Assemblage of Reals in the Drama Classroom: Which Reals? Which Representational Aesthetics? What Theatre-building Practices? Whose Truths?’, Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 40-55.

Geerts, Evelien (2016), ‘New Materialism: How Matter Comes to Matter‘, 14 August 2016, http://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/e/ethico-onto-epistem-ology (last accessed 10 May 2019).

Gray, Emily, Linda Knight and Mindy Blaise (2018), ‘Wearing, Speaking and Shouting about Sexism: Developing Arts-based Interventions into Sexism in the Academy’, The Australian Educational Researcher, pp. 1-17.

Guattari, Felix (2013 [1989]), Three Ecologies, London & New York: Continuum.

Halberstam, Jack (2016), ‘Trans* – Gender Transitivity and New Configurations of Body, History, Memory and Kinship’, Parallax, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 366-375.

Ivinson, Gabrielle & Taylor, Carol (2013), ‘Introduction to Special Issue Feminist Materialisms and Education’, Gender and Education, Vol, 25, No. 6, pp.665–670.

Haraway, Donna (2008), When Species Meet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, Donna (2016), Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin with Chthulecene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Harris, Anne & Yvette Taylor (2016), ‘Sexualities, Creativities and Contemporary Publics’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 503-506.

Hodgins, Denise (ed.) (forthcoming), Feminist Post-Qualitative Research for 21st-Century Childhoods, New York: Bloomsbury.

Holmes, R. (2016) ‘My Tongue on Your Theory: The Bittersweet Reminder of Every-thing Unnameable, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 662-679

Hickey-Moody, Anna (2015), ‘Little Publics and Youth Arts as Cultural Pedagogy’, in Cultural Pedagogies and Human conduct, New York: Routledge, pp.96-109.

Hickey-Moody, Anna (2017), ‘Arts Practice as Method, Urban Spaces and Intra-active Faiths’, International Journal of Inclusive Education, Vol. 21, No. 11, pp. 1083-1096

Hickey-Moody, Anna, Helen Palmer and Sayers (2016), ‘Diffractive Pedagogies: Dancing across New Materialist Imaginaries’, Gender and Education, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 213-229.

Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka (2015), Reconceptualizing Qualitative Research: Methodologies without Methodology. London: Sage Publications.

Laing, Karen, Laura Mazzoli-Smith & Liz Todd (2017), ‘The Impact Agenda and Critical Social Research in Education: Hitting the Target but Missing the Spot?’, Policy Futures in Education, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 169 – 184.

Lather, Patti & Elizabeth St. Pierre (2013), ‘Post-qualitative Research’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, Vol. 26, No. 6, pp. 629-633.

Lenz Taguchi, Hillevi (2013), ‘A Diffractive and Deleuzian Approach to Analysing Interview Data’, Feminist Theory: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, No. 13, pp. 265–281.

MacLure, Maggie (2011), ‘Qualitative Inquiry: Where are the Ruins?’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 997-1005.

MacLure, Maggie (2015), ‘The ‘New Materialisms’: A Thorn in the Flesh of Critical Qualitative Inquiry?‘, in Gaile S Cannella, Michelle Salazar Pérez, et al. (eds), Critical Qualitative Inquiry: Foundations and Futures, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Manning, Erin (2016), The Minor Gesture, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Manning, Erin & Brian Massumi (2014), Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Marks, Laura & Dana Polan (2000), The Skin of the Film, Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 162.

Massumi, Brian (2013), Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Massumi, Brian (2015), Politics of Affect, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Massumi, Brian (2017), The Principle of Unrest: Activist Philosophy in the Expanded Field, London: Open Humanities Press.

Pedersen, Helena & Barbara Pini (2016), ‘Educational Epistemologies and Methods in a More-than-human World’, Educational Philosophy And Theory, Vol. 9, No. 11, pp. 1051-1054.

Quinlivan, Kathleen (2018), Exploring Contemporary Issues in Sexuality Education with Young People: Theories in Practice, New York: Springer.

Renold, Emma (2013), Boys and Girls Speak out: A Qualitative Study of Children’s Gender and Sexual Cultures (ages 10-12), Cardiff University, Children’s Commissioner for Wales and NSPCC Cymru.

Renold, Emma (2016), Agenda: A Young People’s Guide to Making Positive Relationships Matter, Cardiff University, Children’s Commissioner for Wales, NSPCC Cymru/Wales, Welsh Government and Welsh Women’s Aid.

Renold, Emma (2018), ‘Feel what I feel’: Making Da(r)ta with Teen Girls for Creative Activisms on How Sexual Violence Matters’, Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, p. 37-55.

Renold, Emma (2019), ‘Reassembling the Rule(r)s: Becoming Crafty with How Gender and Sexuality Education Research Comes to Matter, in Up-lifting Gender & Sexuality Study in Education & Research, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Renold, Emma & Jessica, Ringrose (2011), ‘Schizoid Subjectivities? Re-theorizing Teen Girls’ Sexual Cultures in an Era of Sexualization’, Journal of Sociology, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 389-409.

Renold, Emma, Sara Bragg, Carolyn Jackson & Jessica Ringrose (2017), How Gender Matters to Children and Young People Living in England, Cardiff: Cardiff University.

Renold, Emma & Gabrielle Ivinson with the Future Matters Collective (forthcoming), ‘Anticipating the More-than: Working with Prehension in Artful Interventions with Young People in a Post-industrial Community, Anticipations Special Issue: Futures: The Journal of Policy, Planning and Future Studies.

Renold, Emma & Jessica Ringrose (2017), ‘Pin-balling and Boners: The Posthuman Phallus and Intra-activist Sexuality Assemblages in Secondary School’, in The Palgrave Handbook of Sexuality Education, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 631-653.

Renold, Emma & Ester McGeeney (2017a), The Future of the Sex and Relationships Education Curriculum in Wales, Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Renold, Emma & Ester McGeeney (2017b), Informing the Future of the Sex and Relationships Education Curriculum in Wales, Cardiff: Cardiff University.

Renold, Emma, Sally Holland, Nicola J. Ross & Alexandra Hillman (2008), ‘Becoming Participant’ Problematizing ‘Informed Consent in Participatory Research with Young People in Care’, Qualitative Social Work, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 427-447.

Ringrose, Jessica & Emma Renold (2012), ‘Slut-shaming, Girl Power and ‘Sexualisation’: Thinking through the Politics of the International SlutWalks with Teen Girls’, Gender and Education, Vol. 24, No 3, pp. 333-343.

Ringrose, Jessica, Rosalind Gill, Sonia Livingstone and Laura Harvey (2012), ‘A Qualitative Study of Children, Young People and ‘Sexting’, A Report Prepared for the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, London.

Ringrose, Jessica & Renold, Emma (2014), ‘F** k Rape!’: Exploring Affective Intensities in a Feminist Research Assemblage’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp 772-780.

Ringrose, Jessica, Emma Renold, Anna Hickey-Moody & Jayne Osgood (2015), ‘Feminist Posthuman and New Materialism Research Methodologies in Education: Capturing Affect’, Conference, May 2015, University College London, Institute of Education & Middlsesex University, London.

Ringrose, Jessica, Katie Warfield & Shiva Zarabadi (eds) (2018), Feminist Posthumanisms, New Materialisms and Education, London & New York: Routledge.

Schott, Robyn May & Dorte Marie Søndergaard (eds) (2014), School Bullying: New Theories in Context, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snaza, Nathan, Peter Applenbaum, Siân Bayne, Dennis Carlson, Marla Morris, Nikki Rotas, Jennifer Sandlin, Jason Wallin & John Weaver (2014), ‘Toward a Post-humanist Education’, Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 39-55.

Springgay, Stephanie & Zofia Zaliwska (2016), ‘Learning to be Affected: Matters of Pedagogy in the Artists’ Soup Kitchen’, Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 273-283.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth (2013), ‘The Appearance of Data’, Cultural Studies-Critical Methodologies, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 223–227.

Stewart, Kathleen (2007), Ordinary Affects, Durham: Duke University Press

TallBear, Kim (2015), ‘Theorizing Queer-inhumanisms: An Indigenous Reflection on Working beyond the Human/Not-human’, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2-3, pp. 230-235.

Taylor, Carol & Christina Hughes (2016), Posthuman Research Practices in Education, London: Palgrave MacMillan.

van Der Tuin, Iris (2016), Generational Feminism, London: Lexington Books.

Wang, Qingchun, Sara Coemans, Richard Siegesmund & Karin Hannes (2017), ‘Arts-based Methods in Socially Engaged Research Practice: A Classification Framework, Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary, Vol. 2, No.2, pp. 5-39.

Weheliye, Alexander G. (2014), Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human, Durham: Duke University Press.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey