How to Hack Study Regulations

by: Caroline Dath , January 27, 2020

by: Caroline Dath , January 27, 2020

Our lives and ways of living seem to have become increasingly managed—framed by contracts, laws and sets of regulations. Reviewing such regulatory texts and practices from a feminist point of view, particularly when the reviewer sits inside of an educational institution, can serve as an act of feminist pedagogy.

Typically, when you enter a community, you inherit the rules of that community. They have been established over time, reflecting a mentality of an era, sometimes a past long gone. And yet, they govern our daily lives. It is through them that the patriarchy holds sway. You are expected to accept, submit and follow them, and heaven forbid, you dare call them into question.

The Context

Our performative action, an active rebellion against the covert operations of patriarchy, which this article describes, took place at the École de Recherche Graphique (E.R.G.) in Brussels, Belgium. We prefer to write it as ‘the erg’ because then it reminds us of the name of the unit of energy derived from Greek ergon (εργον).

The erg’s pedagogical project is to forge a series of practical and discursive tools that can be freely appropriated by students, whatever direction their artistic practice may take in the future. Thus, teaching at the erg prioritises experimentation. Research is instituted via consideration of methodologies, fields of investigation, discourses and economies, as well as trans-disciplinary dialogues. Indeed, in some of our classrooms, teachers and students practise horizontal pedagogy where self-evaluation encourages them to share power and authority in a group. In such cases, the erg’s project leads to a collective pedagogical practice. In these days of political, environmental, social and economic confusion, not only do we invite our students to experiment with innovative ways of approaching their assignments, but also to situate their work within the broader context of the art scene. They are encouraged to engage in critical thinking and collectively negotiate budgets required for art projects to understand how their practices connect with their surrounding environments.

Like many art schools, the erg promotes itself as a very open-minded institution, which employs a whole range of nice people who cherish freedom and equality. Despite this, systemic discrimination still sometimes leads to instances of sexism, racism, homophobia and transphobia; after all, the erg is part of society. Its students are primarily white and economically privileged. Only a few of them had to apply for scholarships to be able to afford their courses. Teachers are also mainly white and privileged, as in so many art schools across the West. For example, the Masters program at the erg—the school’s most prestigious qualification—is managed by six straight white men in their fifties.

In 2016, Laurence Rassel, a well-known cyber-feminist, became the director of the erg. This crucial moment in the history of the school prompted several people to come out as queer, feminist, or simply concerned about gender diversity politics at their workplace. A research group, Teaching to Transgress* was formed. [1] We named it after a text that inspired us—bell hooks’ book, Teaching to Transgress : Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994). I got involved in the group, because for ten years of my teaching in Graphic Design at the erg, I have been growing increasingly worried about the lack of support for students developing projects on gender and sexual orientation. They had difficulties to find allies among the pedagogical team.

Creating R.E.I.N.E

Each year, a research symposium takes place at the erg. In January 2018, the decision was made to create a special edition of that annual symposium, which was provocatively titled: ‘No Commons without Commoning’. Rather than having speakers delivering talks over two full days or so, we set up empty tables in the largest room of the school. ‘No Commons without Commoning’ aimed to connect to ordinary stories and experiences in all forms and practices: words, modes of image-making, objects and spaces—whatever represented the common people or expressed their mindsets and circumstances.

Our group, Teaching to Transgress* sat at one table in the room. We waited until we attracted some attention. When we were joined by a group of ten students and members of staff, we began to discuss what makes a framework for a community. The conversation led us to look at the Study Regulations, and we all had an urge to re-write it using a feminist, post-colonial and queer perspective. As a result, we created a new text. (See the full text at the end of this article). It was a fabulation, something you could find in a near-future sci-fi book, supposedly written for our school after its power structures would have been overturned. Exaggerating the scale of changes that were needed, I admit, we wrote it with a healthy dose of humour and even more enthusiasm. After the symposium concluded, we secretly continued working on the text of our new Study Regulations, more or less for the following two months, until it was ready to be sent to all staff and students at the erg.

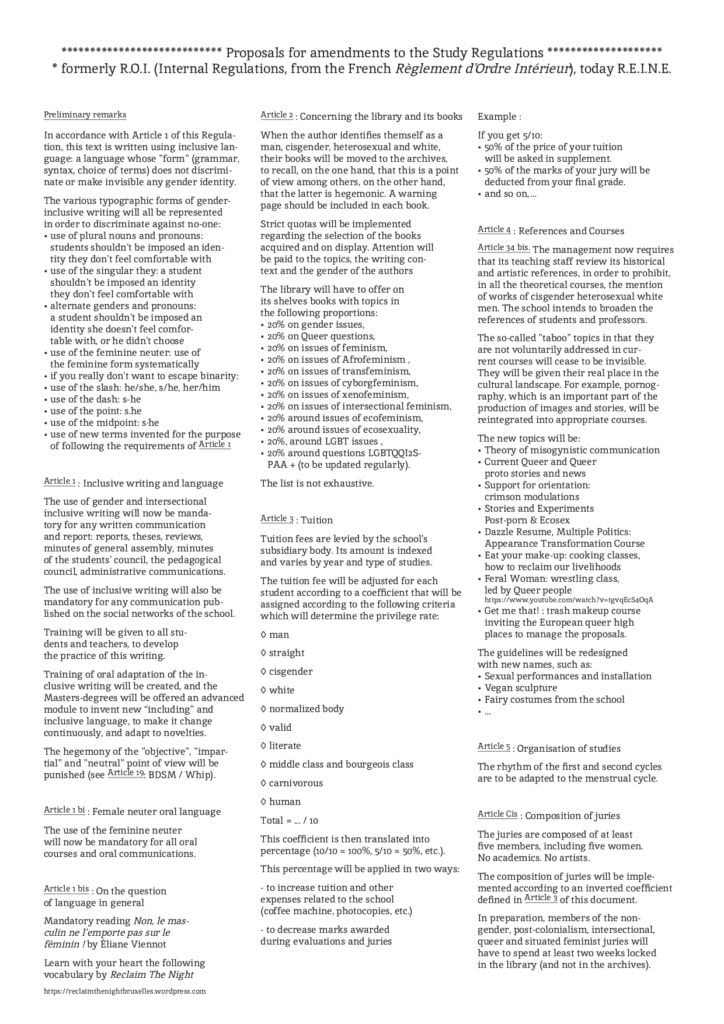

To start with, we changed the title of the Study Regulations (Règlement d’Ordre Intérieur) from R.O.I meaning ‘king’ in French, to R.E.I.N.E. meaning ‘queen’. The formatting of our R.E.I.N.E. mimicked the visual codes used in the original administrative document (numbering of the articles, typographic choices, columns, etc.) to disguise the fact that we were radically challenging the system. R.E.I.N.E consisted of Preliminary Remarks and thirteen new, detailed Articles outlining what turned the current Study Regulations at the erg on its head.

Once the erg’s director gave us her permission, R.E.I.N.E. was sent officially to all staff and students in the guise of the real new Study Regulations. A general meeting (the General Assembly) to discuss each point of the new regulations was called to take place on 20 April 2018.

Criticism

Once the document went out, we received several queries, including some ideological attacks. One of the main complaints was that ‘feminism is an ideology—you can’t bring it into school, you have to stay neutral’. We had to explain that by re-writing the Study Regulations, we wanted to demonstrate how its norms and rules are deeply patriarchal, and therefore, in themselves ideologically driven.

At that point, some of our less-favourable colleagues realised how deeply the patriarchy was ingrained in our supposedly open-minded school—how each posture and behaviour was, indeed, ideological. How could it not be?

We tried as much as possible to move beyond the gender divide, to think through transfeminism and to rid ourselves of gender binaries, whether or not we identified as trans. Still, not everyone was happy: ‘You’re calling for more freedom, but you want to instigate rules and frameworks too’, advocated our adversaries—unsurprisingly mostly white men over fifty who didn’t seem to notice how many rules they themselves imposed all the time. For once, we played with their system. When inequalities affected them, when they were afraid to lose privileges, they reacted immediately.

Of course, we didn’t want to impose new rules, but rather to discuss them collectively. That’s why the general meeting was called one month after the text was disseminated. We intended to bring together all staff from the school—anyone who wanted to participate, from scholars and teachers to administrative staff. At that time, we were told that we were acting as ‘a commando’, but the people who spoke about us in such terms did not come to express their point of view at the General Assembly.

Reflecting on Responses & Outcomes

I will not go through all the articles one by one, but I can describe some of them and the real (re)actions that took place at the school after that General Assembly which gathered around fifty members of the erg.

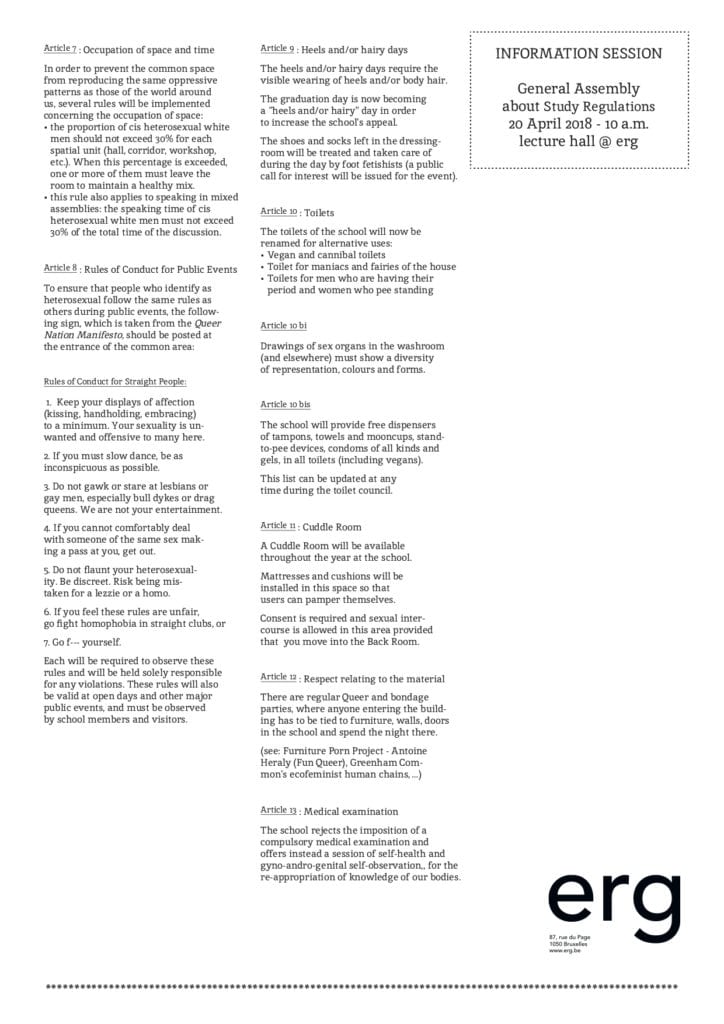

First, some of our colleagues thought it was the new official text of the Study Regulations; they were taken in by the fiction. Presumably, they had not read all the way through, or they would have noticed the surreal humour of the later parts. For example, Article 12 stated: ‘There are regular queer and bondage parties, where anyone entering the building has to be tied to furniture, walls, doors in the school and spend the night there’.

It’s perhaps somewhat ironic that even a tutor from the Speculative Fabulation course was fooled. Now our performative action is used as one of the case studies on that course—the best compliment we’ve ever received!

Most people probably stopped reading at Article 1 about inclusive writing—a hot topic in 2018 in the French-speaking community. On this note, we received an email from a colleague who wrote: ‘As a linguist and specialist in grammar, I regret not being able to be with you. I could have presented the neutral and objective point of view of both grammar and linguistics on this subject.’ It is worth noting that this man—who wasn’t present at the General Assembly (so symptomatic!)—didn’t forget to mention his professional qualifications.

As Éliane Viennot’s book titled Non, le masculin ne l’emporte pas sur le féminin ! (2014) shows, masculinising of the French language was a political decision during Richelieu’s period. Unfortunately, our male colleague who wanted to encourage a more neutral stance had failed to recognise that his ‘objectivity’ has roots in historically established patriarchal conventions of power demonstration through discourse which he willingly employed in his email.

Who else wants to talk about neutrality? Ready for the whip from R.E.I.N.E? Its Article 1 said: ‘The hegemony of the “objective”, “impartial” and “neutral” point of view will be punished’.

***

By ‘punishing’ covert patriarchal discourses of power, R.E.I.N.E advocated a shift towards inclusivity. Our dedication to inclusive writing appeared as an opportunity, particularly in the field of typography, to imagine other possibilities for non-binary representation inside a set of typographic glyphs. To continue the debate about inclusive writing, six months after the Study Regulations meeting, we organised a one-week workshop called ‘Bye Bye Binary’. [2] We invited twenty five type designers and activists to design together what could be the future of our own writing and language, even going as far as creating new suffixes to form new lexical units. This workshop proposed to explore new graphical and typographic forms, including new glyphs (letters, ligatures, midpoints, linking or symbiosis elements). Research in this subject area now continues at the erg in 2020 as part of the Teaching to Transgress Toolbox program.

***

R.E.I.N.E ‘s Article 2 proposed developing a physical and digital pirate library for sharing activist texts, as well as for sectioning and clearly marking all books by those authors who had been privileged:

Article 2: When an author identifies themselves as a man, cisgender, heterosexual and white, their books will be moved to the archives, as reminder that, on the one hand, theirs is just one point of view among others, and on the other, that this point of view is hegemonic.

This idea inspired a very active little group of students and teachers, who soon after the General Assembly embarked on developing such a physical and digital space, using a homemade book scanner.

***

Article 3 called for adjusting tuition fees for students, with more privileged paying more and less privileged less. It was inspired by an experiment led by a pop-up lesbian bar in Brussels called ‘Mothers and Daughters’. The managers of the bar decided to display two price lists for drinks. If you self-identified as a privileged person, you were charged a higher price, and if not, your drinks were cheaper. When customers were offered this double price list, they tended to pause and reflect on their own privilege in society. For example, ‘Ok, I am a girl, but I am white, I have a job and I am in good health so I can pay the higher price to compensate for my higher standing in the community.’ [3]

***

In Article 4, we wrote a long, and to be honest, quite utopian list of new radical art courses that could potentially attract members of various social minorities, because they recognised the less-privileged contributions to both art history and the contemporary world of arts. In 2018, I paired with another lecturer from the erg, Stéphanie Vilayphiou to co-create the Digital Non Binary module, which interrogated how dominant groups—privileged because of their national or ethnic origins, gender, sexuality, age or social class—who partake in designing digital objects (tools, interfaces, algorithms) tend to influence minorities. We were both quite proud when our new module got included in the official list of courses available to students at the erg. For once, we were not left in the margins. A small win but how satisfying.

***

Article Cis, which was six in the row but we refused to call it so, provocatively, demanded to exclude all men from the composition of any judging panels: ‘The juries are composed of at least five members, including five women.‘ After our performative action, the management board set up a quota system to ensure equal gender representation in such panels. It is somewhat unbelievable that it took so long for something like that to come into effect.

***

Influenced by The Tyranny Of Structurelessness (1972) by Jo Freeman and determined to make sure that all voices are considered equal in HE, Teaching to Transgress* tried to design some protocols regarding the use of various spaces. A record of our ideas, claims and propositions has been published online. Rather than a finished product, it is an on-going project which welcomes suggestions from all contributors. [4] It was developed as our real-life implementation of what R.E.I.N.E suggested in Articles 7 & 8:

In order to prevent the common space from reproducing the same oppressive patterns as those of the world around us, several rules will be implemented concerning the occupation of space:

- the proportion of cis heterosexual white men should not exceed 30% for each spatial unit (hall, corridor, workshop, etc.). When this percentage is exceeded, one or more of them must leave the room to maintain a healthy mix.

- this rule also applies to speaking in mixed assemblies: the speaking time of cis heterosexual white men must not exceed 30% of the total time of the discussion.

***

When thinking about spaces, we did not forget about the least discussed rooms where patriarchy seems to have been holding its fort the strongest, namely the toilets. R.E.I.N.E’s Article 10 read:

The toilets of the school will now be renamed for alternative uses:

- Vegan and cannibal toilets

- Toilet for maniacs and fairies of the house

- Toilets for men who are having their period and women who pee standing.

The signage on the toilet doors was soon sorted by one of our students, Justine Sarlat. To make the toilets more inclusive and available to all genders, Justine replaced existing signs on toilet doors with drawings of urinals and toilet bowls. It seems to make so much sense to show what you will find behind the door instead of trying to represent people with patriarchal symbols of gender distinction, such as, for example, skirts and trousers.

***

Although it may seem old-fashioned, Belgian HE institutions require all students to undergo a medical check-up before they can graduate. It, however, can be a very unwelcome requirement, even seen as an intrusion of privacy, particularly for people in the process of gender transitioning. We did not forget about it when working on our version of the Study Regulations: ‘The school rejects the imposition of a compulsory medical examination and offers instead a session of self-health and gyno-andro-genital self-observation, for the re-appropriation of knowledge of our bodies.’ The erg’s administrative staff asked higher authorities to allow the erg to choose their doctor rather than having one assigned to the school. A response remains to be seen.

***

Since the arrival of Laurence Rassel, the erg has made much progress in the way spaces are used to accommodate more social and cultural diversity and to depart from patriarchal conventions. This project, transforming the school’s Study Regulations, emerged from the physical space of the table that Rassel gave to the Teaching to Transgress* group during the symposium ‘No Commons Without Commoning’ in 2018. We did not know what we were going to do, which was very scary. But the project germinated, sprouted, and bloomed. And finally, as the above shows, some of its postulates came to fruition. When in 2019 a few members of Teaching to Trangress* published an article in Culture & Démocratie, among other conclusions, they claimed that offering a sense of ownership of time and spaces to students and scholars is where the feminist practice of pedagogy starts. [5]

***

Perhaps the most significant outcome of our performative action is that it could be repeated in other contexts, in other places and institutions—from sport clubs, through schools, to workplaces. Try replicating what we did in your institution or community. And from now on, when you join a new community, don’t hesitate to question the rules that govern your team or a group. Because patriarchy isn’t dead, the very act of interrogating regulations can be the best, and probably one of the most productive ways of implementing feminism in the everyday life.

Notes

[1] Teaching To Transgress* is an initiative which started at the erg in 2017 to create spaces for teachers and students to exchange experiences around questions of gender, post-colonialism, and intersectional, queer and situated feminisms in the pedagogy of art. Teaching To Transgress* is an attempt to fill a gap in art schools, where people who are trying to address these topics must often do so in isolated ways, in the margins of official programs. Several encounters have taken place from 2017 to 2019, gathering people coming from different countries, different schools and different artistic and theoretical fields. From October 2019 to June 2021, Teaching To Transgress* will be extended to a 2-year international Erasmus Programme, Teaching To Transgress Toolbox for fellows from the erg Brussels (Belgium), I.S.B.A. Besançon (France) and Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg (Sweden).

[2] See www.genderfluid.space (last accessed 15 January 2020).

[3] See www.mothersanddaughters.be/menu-food (last accessed 15 January 2020).

[4] See https://annuel.framapad.org/p/teachingtotransgress-discussions (last accessed 15 January 2020).

[5] See www.cultureetdemocratie.be/productions/view/culture-la-part-des-femmes (last accessed 15 January 2020).

REFERENCES

Adamczak, Bini (2016), ‘Come On. About a New Word Allowing to Speak Differently about Sex’, Mask Magazine, www.maskmagazine.com/the-mommy-issue/sex/circlusion (last accessed 16 August 2019).

Freeman, Jo, aka Joreen (1972), ‘The Tyranny Of Structurelessness’, www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm (last accessed 16 August 2019).

hooks, bell (1994), Teaching to Transgress : Education as the Practice of Freedom, Oxford: Routledge.

Viennot, Éliane (2014), ‘Non, le masculin ne l’emporte pas sur le féminin !’, Donnemarie-Dontilly: Éditions iXe.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey