Feminism as Celebration: Photography & Abortion Activism in Argentina

by: Erika Teichert , October 5, 2023

by: Erika Teichert , October 5, 2023

Introduction

2018 was an unprecedented and, in hindsight, historic year of popular feminist mobilisation in Argentina. Demonstrations, artistic interventions, and photography proliferated in the support of legal abortion, especially during the months leading to the votes in Congress. This was the first time that the legal abortion bill would be voted on—and rejected—in the history of the country, before finally being approved during a second vote in 2020. Photographs in particular were circulated and showcased in both offline and online spaces, contributing to the visibility and popularity of the movement. This article will specifically analyse how photographic narratives were curated to construct a feminist movement in Argentina around notions of celebration and desire, which became particularly prevalent during 2018. The first section of the article will present the Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto, Legal, Seguro y Gratuito (National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe and Free Abortion; henceforth, ‘the Campaign’), especially considering the frameworks mobilised to argue for the right to abortion. The second section will introduce the feminist alliances built by the legal abortion campaign, especially with the transnational movement Ni Una Menos (Not One Woman Less). The final section will analyse the digital photozine, Marea verde (Green Tide), by the photographers’ collective SubCoop, which compiles images of the movement for legal abortion ahead of the vote in August 2018. [1] This article explores how this photographic project mobilised feminist notions of desire and celebration to frame the right to abortion. As shown in the photozine, feminist protest was envisioned during this period as a party, a celebration of feminist values and conviviality. Relying on Ariella Azoulay’s theory of photography (2008 & 2012) and on Giorgio Agamben’s insights into the politics of ‘inoperativity’ (2014), I will analyse the political dimension of celebration as a vehicle for feminist activism.

The Right to Abortion: ‘la maternidad será deseada o no será’

On 1 March 2018, it was announced that the parliamentary agenda would include the debate to legalise abortion. Ahead of the first vote, between 10 April and 31 May, a series of public hearings were held in Congress: 108 hours’ worth of presentations from either side of the argument. Until then, abortion was a punishable crime under the Argentine Penal Code. However, unlike other more extreme examples in Latin America, Argentina did allow for legal abortion in two circumstances: when a pregnancy posed a threat to the woman’s life or health, or when it resulted from rape. Nevertheless, while these exceptions were established in Article 86 of the National Criminal Code back in 1921, the state criminally failed to guarantee access to non-punishable abortions for pregnant women seeking them under these circumstances. Paola Bergallo (2014) has explained the state’s neglect by arguing that an ‘informal rule’ was implemented de facto by conservative groups operating on the fringes of the state. Exploiting the uncertainty around the legal interpretation of the article, these groups effectively prevented the legal exemption of abortion at the time.

The Campaign, composed by a federal alliance of women, was officially launched on 28 May 2005, after initiatives that emerged in the Encuentro Nacional de Mujeres (National Encounter of Women) in 2003. [2] Between 2007 and 2018, the Campaign presented the bill—the Proyecto de Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo (Project for the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy)—to congress a total of six times. However, prior to 2018, the Campaign had never managed to have the bill included in the parliamentary voting agenda. The bill essentially establishes the right to access voluntary abortions up to week 14 of gestation. It is crucial to note that the Campaign also recognises all those who may not identify as women and have the capacity to become pregnant, who are equally contemplated by their proposed legislation. Likewise, while for the purpose of this article I mainly refer to women, I also wish to recognise all those individuals who are equally affected by the issues developed here.

While various discursive frameworks exist with respect to abortion, the Campaign has predominantly framed abortion as a human right (Sutton & Boreland 2019): ‘We assume a commitment to the integrality of Human Rights, and we defend the right to abortion as a just cause to recover the dignity of women and with them, that of all human beings’ (Campaña Nacional, n.d.). [3]

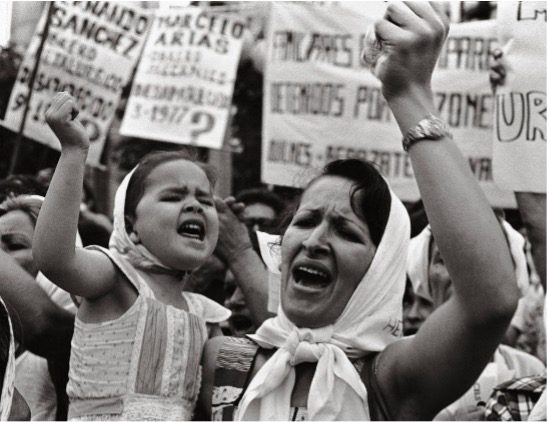

At the same time, the Campaign importantly inscribes the right to abortion within local narratives and histories of human rights activism. The green handkerchief, which Barbara Sutton and Nayla Vacarezza have described as a ‘mandatory presence’ in the Campaign’s visual and material culture (2020, 739), is evidently inspired by the Madres de Plaza de Mayo’s (Mothers of Plaza de Mayo) emblematic white handkerchief. With this symbol, the Campaign is establishing a lineage of activism that dates back to the Madres’ beginnings, claiming for their children who had been disappeared by the last military dictatorship (1976-1983). In 1977, the Madres took part in the pilgrimage to Luján organised by the Argentine church, which had around 1 million participants. To recognise each other and to make their demands visible, the Madres wore their children’s cloth diapers as handkerchiefs around their heads. As time progressed, a white handkerchief was adopted as the now-internationally recognised symbol of their movement. The Madres marked the emergence of the modern human rights movement in Argentina. And while the Madres and the activists for the right to abortion have a very different rhetoric about maternity, there is recognition that the former enabled the women’s movement by exiting the domestic space to become political actors. [4]

The Campaign further ‘localises’ the right to abortion by describing it as a ‘debt on behalf of democracy’ (Campaña Nacional, n.d.). The Campaign maintains that the type of violence perpetrated against women during the last military dictatorship (1976-1983) cannot simply be accounted for as ‘state terrorism.’ [5] Rather, it needs to be reframed as gendered and reproductive violence perpetrated against women specifically, for being women. Clandestinidad [6]—a term associated with state-sponsored terrorism and experiences of political repression, censorship, and torture during the dictatorship—has allowed activists to trace a historical continuity of women’s subjugation to reproductive violence within Argentine history. In this way, the term aborto clandestino (clandestine abortion), which is used for penalised or ‘backstreet’ abortions, adopts a particular agenda which invites the re-visitation of the country’s recent history to write a new chronology of gender violence. In this sense, it is significant that those members of Congress who supported the bill often wore the green handkerchief during the votes; a powerful symbol of the state validating this history of violence.

The Campaign also frames the right to abortion as a matter of both public health and social justice. As expected, clandestine abortions are associated with a disproportionate mortality rate in women, as well as potentially severe health consequences (Campaña Nacional 2018, 9-10). At the same time, the Campaign argues that clandestine abortions reflect a wider problem of inequality, given that women across the country are disparately affected depending on which province they live in and their socio-economic background (10). It is common knowledge that, even when voluntary abortions were illegal, safe abortions were available to those who could pay for them, making unsafe abortions a reality only for those unable to afford them.

The Campaign mobilised a further argument in favour of the legalisation of abortion: women’s autonomy over their own bodies. The question of autonomy became, arguably, one of the most contentious implications of the bill. The Campaign’s position is that ‘the decision or will of a woman or a person with the ability to become pregnant is sufficient reason to decide’ (Campaña Nacional 2018, 8). The issue of autonomy is controversial, in part, because abortion sits uncomfortably within the private and the public. As the debate in Congress illustrated, while in many cases abortion was regarded as an unsuitable or even immoral solution to a ‘private’ issue resulting from an individual’s (often irresponsible) conduct, the womb was still actively claimed as a space of public regulation because it is perceived to be ‘where life begins.’ At the time of the vote in the upper chambers of Congress on 8 August 2018, numerous senators cast their votes rejecting the bill in order—in their view—to respect the right to life of the foetus, stating their determination to ‘save both lives,’ a pledge that has defined the campaign against the legalisation of abortion. A significant number of lawmakers who voted this way did so explicitly citing their Catholic faith as the underlying reason, despite the Argentine constitution guaranteeing the country’s secular nature.

Natalie Sedacca explains that framing abortion in terms of the right to life of the foetus is indeed deeply informed by the Catholic worldview. As Sedacca explains, there is evidence to suggest that ‘prohibitions on abortion based on foetal rights are not only about the protection of unborn life, but also about confirming particular religious or moral conceptions, which aim to protect the virtue of women’ (2017: 131). In her analysis of the Catholic church’s encyclicals on ‘female nature,’ Julieta Lemaitre further explains that ‘salvation’ for women is intertwined with ‘their fulfilment of the call to motherhood and family life in service and sacrifice’ (242). Valeria Manzano has explored the extent to which the Catholic church and Catholic groups in Argentina shaped abortion legislation in the 50s and 60s, often advocating for more severe penalties for abortion (2015: 8). As expected, the Catholic church vocally opposed the legalisation of abortion in Argentina, as they have done elsewhere (Mariano De Vedia 2018).

To this largely Catholic position, the Campaign mobilised a final argument centred on the notion of desire, which has become one of their most well-known battle-cries: ‘la maternidad será deseada o no será’ (maternity will be desired or it will not be). Desire serves to position maternity away from duty and sacrifice and into the realm of autonomy, choice, and pleasure. Desire, as we will explore below, entered into feminist discourse together with the debate on abortion, determining the tone not only of the demonstrations in support of the bill but also of the feminist movement at large in Argentina, and the spirit of activism it encourages. Desire, as I argue, is inscribed within a wider feminist discourse of celebration as a vehicle for activist change.

Feminist Solidarity: ‘nos mueve un deseo de revolución’

The feminist movement was instrumental in galvanising mass support for the Campaign in the months leading up to the vote in 2018, which in turn resulted in an unprecedented rise in feminist mobilisation. As the Campaign describes, their agenda was promoted by feminist collectives and women’s movements, as well as from women and individuals belonging to a diversity of social and political movements (Campaña Nacional, n.d.). The most significant movement in this regard was Ni Una Menos (henceforth, NUM), which is arguably one of the most prominent and transnational feminist collective in Latin America. The movement was originally founded in Argentina in 2015 to raise awareness of the increasing number of women murdered as a result of gender violence. Since then, the movement built by NUM has expanded to include a diversity of feminist, intersectional causes and struggles, including the right to abortion.

NUM’s publication, Amistad política e inteligencia colectiva (Political Friendship and Collective Intelligence) (2018), compiles a series of their feminist manifestos between 2015 and 2018. In the three-year anniversary of the movement in 2018, the collective declared: ‘we said that we are moved by desire: it is a desire to unite with the active search for dignity for all and our territories … in the face of the advance of capitalist violence. We are moved by a desire for revolution’ (2018: 105). During this time, when the right to abortion was being defended in fervour, the notion of desire entered into the feminist discourse as a crucial affective device to inspire and propel a feminist revolution against both patriarchy and, importantly, neoliberalism.

As Malena Nijensohn has noted, regarding feminist action in solidarity to other struggles against neoliberalism, feminism proposes moving away from identity politics in order to use the issue of precarity as the common denominator for building political alliances (2018: 9). This strategy has expanded still further the possible subjects of feminist struggle, and of and for whom feminism can speak. Essentially, the subject of feminism is a precarious one which has been made vulnerable by neoliberalism and the patriarchal governance of bodies. The desire to build a movement amongst vulnerable and precarious subjectivities has come to define the expansive feminism of NUM. At the same time, it must be acknowledged that such expansiveness has not developed without tensions. In particular, the Movimiento de Mujeres Indígenas por el Buen Vivir (Indigenous Women’s Movement for Buen Vivir) has denounced the lack of plurinationality within the feminist movement, particularly around the issue of abortion. In 2020, they published an article in LatFem demanding that indigenous women’s voices be heard in the reproductive debate. They claim that no genuine debate is possible without the presence of indigenous voices, and without both respecting and circulating their ancestral medicinal knowledge.

Yet, even if these tensions and exclusions exist between feminist voices, NUM consciously emphasises bonds over divisions for the purpose of activism. This is best exemplified in the NUM travelling exhibition Mareadas en la marea (High on the Tide), curated by founding members Cecilia Palmeiro and Fernanda Laguna (Figure 1). [7] Showcasing a range of artivist materials from feminist mobilisation around the world, including references to indigenous women’s struggles over territory, the exhibition functions as ‘a micro-political map of friendship as a revolutionary relationship’ (Laguna & Palmeiro 2018). It foregrounds the creative act of curation, of bringing together objects that on their own would have singular rather than collective stories to tell, to enable a view of feminism as an expansive network. In doing so, the display consciously smooths over any potential conflicts or divisions that may exist within feminism, emphasising activist bonds. As the curators conclude: ‘Even if painful at times, our revolution is a party’ (Laguna & Palmeiro 2018). If divisions exist, the display consciously erases them, in order to perform a constellation of feminist solidarity and togetherness.

This constellation of solidarities has also given shape to the kind of autonomy argued for in the right to abortion. In the words of NUM, this is an autonomy ‘that does not think of the body as private property but that recognises the community framework of all the people we need to live and develop, to take care of ourselves collectively’ (2018: 142). Autonomy and desire—or the desire for autonomy—are expressed and upheld as relational categories, which place women’s bodies in affective and political solidarities to other subjects made vulnerable and precarious under patriarchy as well as neoliberal capitalism.

During this time, however, the feminist revolution was unrolling on an affective spectrum which was premised on, but not limited to, desire. As stated, Laguna and Palmeiro describe the feminist revolution as a party, a celebration. I would like to cite Palmeiro’s own explanation of this idea in full:

The idea of revolution as a party is linked to feminism in its most archaic version, the matriarchal experiments of pre-Christian cultures. Popular ritual traditions include celebrations with music and dance as a way of bringing cohesion to a community by merging all bodies into a common rhythm. That idea, secularised, reappears in contemporary feminism as a way of building community, of entering into joyful empathy, of awakening resonances and correspondences not only with the suffering of others, but with their pleasures as well. Dancing, singing together, with other hundreds of thousands or millions, is undoubtedly an experience of de-subjectivation, of activating by connecting to a collective body as a form of political subjectivity. This is how the tide is experienced, as something to be shaken up. (2019: 23-24)

Palmeiro’s description of la marea verde (the green tide), as the feminist movement was termed as it gained popularity around the legalisation of abortion, emphasises the exercise and celebration of pleasure, joy and movement—and not just the recognition of mutual suffering—as the site where interdependencies and solidarities are meaningfully forged. [8] One of the main aims of this article is to enquire into this affective manifestation as it gained traction during 2018 ahead of the votes on the legal abortion bill in Congress. The ambivalent character of abortion, which can indeed entail experiences of suffering and sorrow, is largely subsumed under the exercise of feminism as a celebration. The tone of the demonstrations ahead of the vote was distinctly marked by the idea of the feminist revolution as a party, celebrating women’s corporeal autonomy to construct affective bonds between the diverse subjects of feminism.

Visual culture and photography played a key role in galvanising support for the Campaign. As Sutton and Vacarezza have observed about the movement in support for the right to abortion, ‘many of the online pictures and part of the graphics denote the collective, the massiveness of the movement … [i]f these images aim to engage the general public, they do so by showing a movement on the rise that does not stop but persists and grows’ (2020: 742). Photographs of the demonstrations ahead of the vote in 2018, I would add, portray a mass movement that is particularly united by the celebration of notions of desire, pleasure, and joy in the manner described by Palmeiro. After the favourable preliminary vote in the lower chambers of Congress in June 2018, Revista Zigurat asked academics and writers to share their impressions of five different photographs of the demonstration. Tellingly, Wanda Fraiman writes,

the scene that the girls were putting together was a carnival: ‘This is a party, there are plenty of people,’ I texted a friend as soon as I arrived at the tube station on Mayo Avenue. Glitter, singing, and dancing … They mobilise with joy … and that is what enabled them to put up a party that lasted almost 24 hours.

In fact, all the contributors often described the demonstration as a party. During this historic time, the feminist movement and the legal abortion campaign came together, fuelling notions of desire and celebration, which became popularised in feminist activism. The following section will focus on photography to consider the changing face of the feminist movement in Argentina. Specifically, I will focus on Marea verde, a digital photozine that features photographs of the mobilisations supporting the right to abortion in 2018, and the way in which the right to abortion was framed around notions of desire and celebration.

Marea verde: ‘inunda las calles con glitter brillantina’

Before looking into Marea verde, it is worth remarking that the campaign against the legalisation of abortion was visually Catholic. They found a collective gathering in the Masses held by the church and heavily mobilised religious imagery. In relation to the photograph shown in Figure 2, taken by the photojournalist Tomás Borgo, Natalia Fortuny describes the atmosphere and framing of the image as follows:

The photo shows a cold and grey sunset (or sunrise?) trimmed by two colours: patriotic baby blue, and barbie baby pink. Visually, there is not a formed group, but scattered individuals who raise balloons and little flags. Unlike other photos of the day of the vigil around Congress, which underline militancy or the collective formation of an identity, in this image there are people whose faces are not discernible because they are turned away or out of focus. Here, the identities are neither clear nor candid, not because they belong to an undifferentiated crowd, but because such is the resource deployed by this photograph (2018).

Before Fortuny’s eyes, the camera is framing the counterdemonstration in specific ways, foregrounding disjointedness and disengagement. By contrast, as we will see, the curatorial choices of Marea verde—as well as other photographic images of the feminist protests that circulated at the time—emphasise the togetherness of the mass feminist movement, using the medium in support of feminist claims to constitute the movement as a dynamic and solid assembly. Despite the ultimately negative vote against the bill in 2018, this photographic project depicted feminism as a thriving, collective, and yet familial force, reassuring us that change would come. In this sense, Marea verde curates feminism as a manifestation of the world it wants to create. In this feminist worldview, desire and celebration are the affects that bind this expansive force together and propel it forward.

During a roundtable at the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero (UNTREF) with NUM in April 2019, Butler remarked upon the term marea verde. As Butler described the metaphor of the tide, ‘it comes again and it receives, it meets another tide, and it produces another constellation. It is an ongoing dynamic, the future of which is not fully known or predictable’ (2019). Their insights point to the dynamism and spontaneity consciously exercised by feminism. However, there is also an inevitability implied in the image of the tide: echoing the physics of natural phenomena, feminism constantly tells us that its revolution cannot be stopped. Indeed, this is the message of the eponymous project, Marea verde, the digital photozine produced in support of the Campaign, which brings together photographs of various demonstrations and interventions carried out around the votes of the legal abortion bill in 2018. As the opening page of the zine states: ‘The Green Tide floods the streets with glitter … [t]he claim is here and everywhere, and blind is every person who does not want to see it. The waters are restless. The tide is alive and, in there, no one is giving up.’ The photozine was coordinated by Sub Cooperativa (SubCoop), a well-established photographers’ collective active since 2004, and Fundación Infoto, a collective based in the province of Tucumán with the aim of supporting activist and academic activities related to human rights. These groups invited submissions through an open call for the 8th Biennale of Argentine Photography that was held in Tucumán in October 2018, and the zine was later published by Sub Editorial—SubCoop’s editorial branch—on the digital platform Issuu. The selection/curatorial committee was composed of Gisela Volá (Argentina), Maya Goded (Mexico) and Ana Casas Broda (Spain/Mexico), and it was edited and designed by Verónica Borsani (Argentina).

The zine is an acknowledgement of the crucial role that digital photography played in the Campaign. During these months, photographs were circulated in great numbers amongst supporters both online and offline. Those circulated through digital and social media played a particularly galvanising role in inspiring support and mobilisation. As Volá states, ‘feminism gained importance in the struggle for rights in all spheres, and has, clearly, also reached the field of photography’ (quoted in Cristina Civale 2018). Tellingly, the photographs showcased over 230 pages of the zine overlap, both thematically and aesthetically, with those exhibited by the Campaign itself in a display entitled Identidades en lucha (Identities in Struggle), which toured around Argentina between 2018 and 2019. For this analysis, however, I have chosen to focus on the photozine rather than this exhibition: the zine contains a higher number of images and performs a more conscious act of curation of a photographic narrative, which does not challenge but furthers the affective narratives mobilised by the Campaign and their exhibition.

Marea verde is a complex project: it belongs to the genre of photojournalism or documentary photography, it is compiled as a sequenced narrative in the form of a photozine, and it is published open access. The selection of the photographs resulted from an open call to which anyone—not just professional photographers—was invited to submit an image, thereby emphasising the democratic nature of the practice of photography. All of these aspects are worth considering in the analysis. However, for the purpose of this article, I will mainly focus on the curation of the zine: on the feminist narrative that is constructed through the sequence of the images. While photobooks are generally defined by a curated sequencing of both text and image (Patrizia Di Bello and Shamoon Zamir 2012, 1), Marea verde only showcases images, thereby investing the photographs with enhanced agency to convey meaning. Nonetheless, the manipulation of temporality through the sequencing of images, another fundamental aspect of the photobook, is very much present in Marea verde. While the images follow a loose timeline—before, during and after the votes in Congress—the various interventions and demonstrations are visually conflated into a single political event. The narrative does not emerge from a chronology, but rather from the images themselves and the dialogues they establish with one another. That the zine was published digitally as a curated narrative stands in contrast with the often isolated and punctuated way in which we tend to consume images online (think of the act of ‘scrolling’). In turn, that Marea verde was published as a digital zine and not as a paper book sacrifices something of the bodily act of reading photobooks—of ‘its sensuous and haptic dimensions’ (12)—in order to prioritise activist dissemination and access.

The photographs included in the zine are both visually and emotionally direct, openly showing the viewer what they want to convey. No epigraphs or author names are provided alongside the photographs. The names of the photographers are included at the end of the zine in order of appearance, but no precise correlation is made between their names and the images. As the introduction reads: ‘Let the movement speak, the symbolism of the cloths, the faces, the public and the private.’ In this sense, the photographs are not meant simply as a ‘record,’ ‘archive’ or documentary ‘coverage’ of the movement. They are also objects of the art of activism, and as such, their purpose is to forge social relations beyond themselves.

Ariella Azoulay theorises photography as an ‘event:’ a creative sphere of action and assembly that the author terms the ‘citizenry of photography,’ which has the potential to forge civic and political alliances (2008). Photography is not just the photographic image, but also the ‘encounter’ that gave rise to the image, as well as the political encounters that will follow as a result of that image. In this sense, to Azoulay, photography has no authorship, to the extent that photography always ‘extends beyond the photographer’s actions’ (11). Photography responds to no one in particular, be it a photographer or a sovereign power. This is what enables Azoulay to claim that photography is always mobilised ‘in the service of temporality’ (2012: 82). That is, as photographs travel and are circulated in different contexts, they continue to be seared with ‘the trace of the plurality of political relations,’ and it is that trace of the collective which transforms ‘what is seen into claims that demand action’ (2008: 25-26). In other words, those who partake in the photographic event can always stand as citizens who forward rights claims, regardless of the ways they may be censored, oppressed, or wronged elsewhere. Following her theory, the unbounded space of ‘borderless citizenship’ (26) enabled by photography would seem to resemble the feminist movement itself: a dynamic, open-ended constellation of vulnerable yet diverse subjects who, in alliance, are able to put forward rights claims and make them visible.

The question follows, however, of how women’s reproductive rights claims are visualised through photographic practice in the fight for legal abortion. There are forms of violence that remain invisible to the eye and, in these cases, it is the work of creativity to figure out how we will render the unrepresentable part of an ‘economy of gazes’ (Azoulay 2008: 113). Indeed, clandestine abortion belongs to the category of unrepresentable violence. Azoulay reminds us that sexual violence does too, knowingly asking: ‘[h]as anyone ever seen a photograph of a rape?’ (217). Like rape, abortion would seem to exist in the realm of discourse but not of visuality. Relegated to the obscured spheres of clandestinidad, secrecy, illegality, as well as sexuality, we can hardly expect photographic representations of the unsafe, inhumane conditions in which women have had to undergo abortions. However, even if there were, or even if they could be re-created in some way, would feminist activism want to expose those who have sought abortions in such circumstances? As Sutton and Vacarezza argue, ‘we need to consider the political implications of using explicit and violent images that can surely touch some audiences but might also position women as sheer victims and abortion as (always) harmful or dangerous’ (2020: 735). In the age of the hyper-production and hyper-visibility of images, there is, perhaps, a certain potency to be found in that which cannot be shown.

This intention, however, stands in sharp contrast with anti-abortion groups, which resort to particularly graphic modes of visualisation. In Argentina, as Claudia Nora Laudano (2011) has studied, these groups have represented the foetus through medical imagery, even publicly performing ultrasounds. Nayla Vacarezza has also remarked upon the use of aesthetic conventions that resemble the fictional genre of horror to represent abortion as a sort of crime scene premised on ‘mutilation, destruction and death’ (2012: 47). By contrast, within the movement for the right to abortion, Vacarezza argues that unsafe abortions have largely been represented by mobilising symbols instead of graphic imagery, such as coat hangers, surgical equipment, parsley plants and pills (2018: 197). These representations are marked by the absence of the body. However, as Vacarezza observes, they are objects that remain connected to, while not graphically depicting, the bodies that undergo abortions, thereby advancing an impression of how these objects have had an effect on them (197). Nevertheless, they still operate within a crucial affective complexity, positioning abortion within a spectrum of emotions, opening a kind of ‘coexistence’ of differing affective experiences (208). As the author explains, through these objects, activists are able to address the suffering associated with abortion while, at the same time, explore the connections that exist between abortions and ‘forms of joy, determination, pride and mutual care’ (197). Vacarezza notes that different objects are used to connote different affective modalities, opening a spectrum of possibility. While several objects are meant to represent the cruel methods of unsafe abortions, the pills, for example, have been presented positively, as the safe possibility of choice and affirmation (207). In this way, the language of suffering is not negated but rather reframed, to implicate an array of affective meaning around abortion that transcends experiences of victimhood. As we will see below, the photozine Marea verde follows a similar logic.

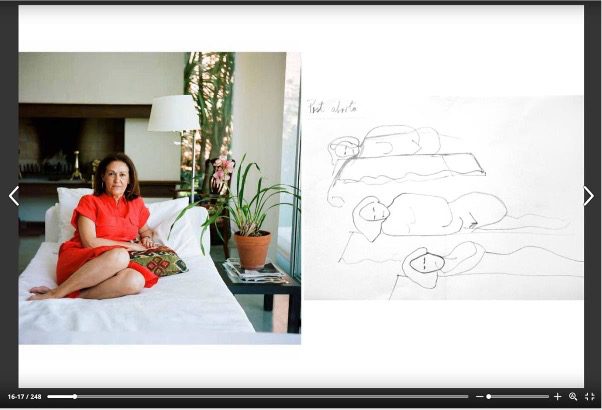

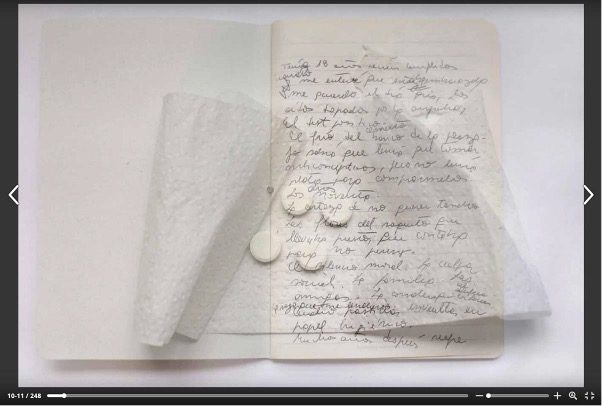

Marea verde begins with subdued representations of unsafe abortions, going on to place them within a larger narrative that emphasises the ubiquity, unity, and empowerment of the feminist movement. The narrative opens with visual symbols of clandestine abortions, then moves on to the widespread use of the green handkerchief and other performative interventions in the public sphere, culminating with the mass vigil during the vote in the Senate. Unsafe abortions are suggested by the usual tropes identified by Vacarezza, with a photograph of a parsley plant (Figure 3) and of a green stencil of a hanger—a popular transnational symbol to represent the suffering of clandestine abortion (Vacarezza 2018: 202)—with the word ‘Adiós’ (‘Goodbye’) above it (Figure 4). [9] However, the photozine displays additional representations of clandestine abortions. At the start, it shows a number of photographs of notebooks scribbled with annotations and doodles, describing the circumstances in which an abortion was carried out. These sketches are sometimes placed beside an accompanying photograph: a poised, colourful portrait usually captured in a domestic space. These works by Georgina García are part of a series entitled Testimonios (Testimonies), which gathers different experiences of abortion. The testimonies, however, are not graphic or explicit. For example, one of the portraits is simply accompanied by a drawing depicting the floorplan of the location where the abortion took place (Figure 5). Another is placed beside a doodle that rather schematically and non-graphically depicts the body ‘post-abortion’ (Figure 6). Another photograph depicts a photomontage of a scribbled notebook, toilet paper, and four pills (Figure 7). The annotations foreground disjointed sensations rather than a cohesive narrative:

I was 18 years old when I found out I was pregnant. I remember the grey day, my ears blocked with anguish. The positive test. The cold bench in the square. I knew I had to take contraceptives, but I didn’t have the money to buy them. The nineties. The certainty of not wanting to have it. The flower pattern in the cardigan I was wearing… the silence… the guilt… four pills wrapped in toilet paper…

As the annotation progresses, it becomes increasingly muddled and illegible. These testimonies of clandestine abortion are subtle and contemplative, seemingly belonging more to the realm of personal memory than of public representation. And yet, as is developed below, the curation of the zine also uplifts these difficult intimate experiences by placing them within a wider narrative of collective affirmation.

The photographs addressing experiences of clandestine abortion are relatively few and confined to the beginning of the zine, which increasingly gives way to images that perform the power of collective, feminist assembly. This curatorial choice reflects Sutton and Vacarezza’s observation that ‘ambiguity and sorrow are likely excluded in a polarized political context where lines need to be drawn and feelings flattened or only deployed strategically to achieve political goals’ (2020: 735). Indeed, the visual narrative enacted by Marea verde purposely does not seek to ‘activate’ viewers through empathy by representing images of pain and suffering. In this sense, reflecting again on the continuities and differences between the Madres and contemporary feminism, it is interesting to compare the photographs in Marea verde to those of the Madres during their demonstrations. The latter, as Cora Gamarnik concluded, are ‘snapshots of pain’ (2013: 82). In this case, the photographic act was, as Azoulay put it, ‘exploiting the photographed individual’s vulnerability’ to respond to the political urgency of the moment (2008: 118). The Madres took their grief into the public sphere and into the photographic event, imprinting on the images the deep poignancy of agony. Photojournalist Eduardo Longoni’s photographs of the Madres’ walking rounds at Plaza de Mayo come quickly to mind. I think of one where one of the Madres is depicted seemingly crying, calling out in pain, pleading to everyone and to no one in particular: it is the kind of striking representation of loss and agony that provokes a visceral response (Figure 8).

While there are no such images in Marea verde, there is an important overlap with images of the Madres: that is, the representation of solidarity among women. In the zine, for example, there are two adjacent photographs that place different generations of women in dialogue with one another. On the left, an older woman is depicted tying a green handkerchief around her head; and on the right, a younger woman ties it in the same way around a girl who could be her daughter (Figure 9). The visual dialectic, if simple, effectively enacts a bond based on intergenerational solidarity. The second photograph also finds a parallel with the iconic photograph by Adriana Lestido entitled Madre e hija (Mother and Daughter) taken during the Madres’ demonstration in 1982 (Figure 10). The message of solidarity between mothers and daughters, older and younger women, is clear in both. Yet the tone is very different. Lestido’s image visibilises a clear urgency of protest and demand in the face of unknowability and uncertainty, which is lacking in the image in Marea verde. Indeed, these photographs in Marea verde are framed to display a calm composure that communicates a sense of determination and conviction rather than urgency.

That is not to say that there is no anger in Marea verde, but it comes across as a conscious performance of defiance. The anger displayed does not emerge from a moment of confrontation. Violence and repression, by contrast, are expectedly very prevalent in images of the Madres during the dictatorship. Once again, one need only think of Longoni’s emblematic shot of the Madres being subjected to repressive action on the part of mounted police at the Plaza de Mayo in 1982 (Figure 11). By contrast, under certain democratic protections, albeit imperfect, the most confrontational images in Marea verde pertain to the realm of symbolic power. One image captures a demonstrator walking forward towards a formation of police officers with their arms stretched, as if performing an act of resistance and martyrdom (Figure 12). The zine also presents various images of women staring defiantly into the camera, some covering their faces with the green handkerchief (Figure 13). These photographs are gestures to the possibility of conflict rather than conflict itself, producing images that inspire rather than bear witness to the frictions of protest. Echoing the affective solidarity exercised by the feminist movement, conflict is largely erased from Marea verde, continuously capturing bonds over divisions, and sentiments of empowerment over powerlessness.

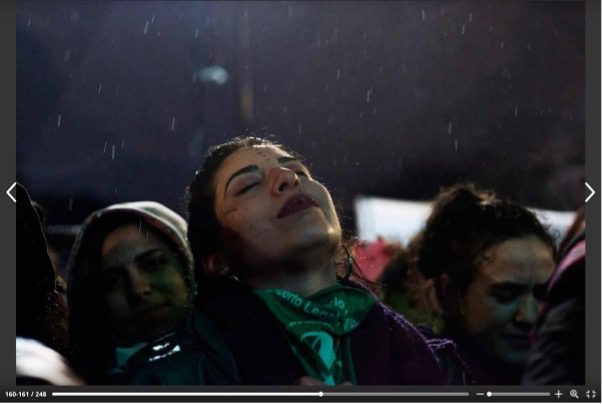

The zine predominantly opts for a different affective device: the celebration of and by the body in protest. As the photozine progresses, the most prevailing and distinct photographs are those that capture forms of joy, pleasure, and play. Bodies engaging in dance (Figure 14); bodies rejoicing in the act of protest, with their handkerchiefs in the air (Figure 15); bodies kissing as part of their demonstration (Figure 16); a woman simply closing her eyes, feeling the drizzle of rain falling on her face in the middle of the night, bearing an expression of joyous ease (Figure 17). In this way, the photographs increasingly perform notions of desire and celebration, foregrounding these as the principal emotions upon which the social relations in and beyond the images are forged. Tellingly, Palmeiro describes the vigils during the votes as resembling ‘a festival and a coven’ where ‘the tide in all its diversity was abuzz’ (2018: 562). One might question, however, the political potential of such representations. Specifically, we might consider the extent to which they are able to reach out to new audiences to join the feminist ranks, or whether they mainly serve to reaffirm and strengthen the collective that already exists. What, in short, is the political validity of a feminist party?

Thinking with Giorgio Agamben, we might put aside for a moment the frivolity that may come to mind when thinking of parties. Agamben proposes the political potential of what he terms ‘inoperativity’ (2014). Inoperativity should not be taken to mean ‘the cessation of all activity’ but rather the suspension of activities tied to notions of productive labour, thereby ‘opening them to a new possible use’ (2014: 69). To the author, la festa (the party) is the principal site where inoperativity reigns supreme. La festa always entails ‘a destitutive element’ that serves to provisionally suspend, and thus render inoperative, productive activities (70). That is to say, while in parties and celebrations we also ‘do things,’ we do them while abstracting them from their economic or productive value: ‘If one eats, it is not done for the sake of being fed; if one gets dressed, it is not done for the sake of being covered up or taking shelter from the cold … if one exchanges objects, it is not done for the sake of selling or buying’ (69). At parties, we devoid our embodied activities of economic value, enabling our bodies to respond to a different set of principles and purposes. Following Mikhail Bakhtin’s (1984 [1965]) thought on carnivals but adapting it to a capitalist-neoliberal setting, Agamben upholds the political potential of parties to the extent that they create a space where relationships and communities are sustained by different values than those of capital and productivity.

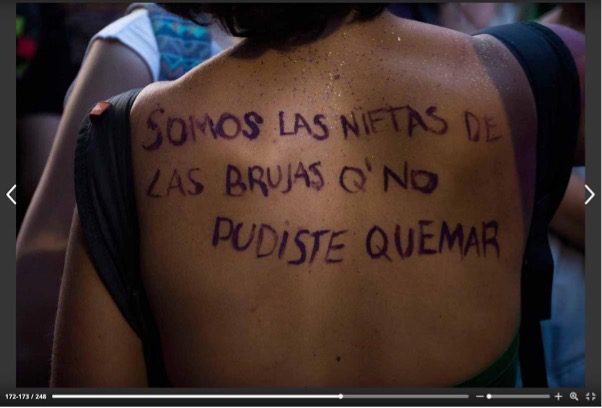

Dancing, costumes, kisses: all those elements that Agamben sees as intrinsic to the political inoperativity of parties are some of the most defining elements of the feminist celebration held during demonstrations for the right to abortion. Photographs of women transforming their bodies for the celebratory occasion prevail in Marea verde: women wearing green as their costume in the form of glitter, make-up, and hair dye (Figures 18, 19 and 20); nude bodies inscribed with messages (‘we are the granddaughters of all the witches you could not burn’), revealing the body as materiality, an empty canvas to be inscribed with new meanings and narratives (Figure 21); women kissing; women dancing. ‘What is dance,’ asks Agamben, ‘other than the liberation of the body from its utilitarian movements, the exhibition of gestures in their pure inoperativity? And what are masks … if not, essentially, a neutralization of the face?’ (2014: 70). Following this line of thinking, could we conceive of the naked female body in protest as the abstraction of nudity from its commodity value? Could the celebration of desire and pleasure be the suspension of the reproductive ‘productivity’ of biological functions? One might claim that demonstrations are usually spaces of subversion in which the normative rules of capital are put to the test by virtue of their temporary suspension. But a demonstration that is actively envisioned as a party perhaps can be read as a particular critique of capitalism and the hierarchical value system that sustains it: a critique that, as we have seen, lies at the core of Argentine feminist thought on neoliberalism and patriarchy. In this sense, these feminist discourses around neoliberalism should be placed in dialogue within wider global concerns about sustainable living. Feminist activist and academic, Silvia Federici, has assessed that ‘worldwide a consciousness is taking shape … that capitalism is “unsustainable” and creating a different social economic system is the most urgent task for most of the world population’ (2019: 23). I see feminism’s notions of celebration and desire as speaking to such anxieties.

Agamben further argues that inoperativity should be at the centre of alternative, revolutionary political visions. So far, revolutions have fought to constitute rights, following a tradition of constitutive power. Agamben proposes a different avenue: not a form of power formation, but a potency, a force that comes to destitute political structures to engender a new possibility of living. To him, the revolutionary focus should not be on the actions we take, but rather on what kind of life we choose to live: ‘the destitution of power and of its works is an arduous task, because it is first of all and only in a form-of-life that it can be carried out. Only a form-of-life is constitutively destituent’ (2014: 72). While feminist activism obviously uses the legal framework and does seek to constitute rights, at the same time, feminism lies above and beyond governance. Indeed, at the core of feminism is not the creation of a further structure of power, but rather the creation of a new way of life, which is palpable in the affective relations that Marea verde exercises. In the words of Ni Una Menos: ‘[w]e invent the world we want to live in’ (2018: 4). The photographic account constructed in Marea verde materialises the feminist world that is to come: the sequential narrative sets in motion an alternative political possibility where feminist values guide our embodied experiences with ourselves and others.

However, if the potential of inoperativity resides in the suspension of governance, as Agamben suggests, the question remains: how does inoperativity relate to citizenship, law, and rights claims? While working within the legal structures available to protect women and vulnerable subjects, feminism also wants to bring about the deconstruction— ‘destitution,’ thinking with Agamben—of power as we know it. Feminism—or at the very least, the feminism we have explored here—does not conceive of a way of doing this without tackling what it understands as the foundations of contemporary inequality. This involves questioning conceptions not only of gender, but of capital, the market, enterprise, competition, wealth, labour—all those ‘strategies’ and structures through which capitalism and neoliberalism have divided us—as well as questioning what feminism understands as the patriarchal foundations of governance and law-making. Borrowing the words of Azoulay, feminism understands that ‘citizens cannot be equally governed if they are governed with others who are not governed as equals’ (2008: 25). Indeed, a feminist vision of citizenship is premised on the exercise of solidarity as the fundamental recognition of unequal existences.

Following his argument, Agamben describes both art and politics as ‘the dimension in which the linguistic and corporeal, material and immaterial, biological and social operations are made inoperative and contemplated as such’ (2014: 74). I see the photo-narrative of Marea verde as inscribed within this framework of inoperativity. Photographic practice—a space which, as Azoulay describes, responds to no sovereign by existing beyond any form of governance—is perhaps an exemplary site from which to suspend structures of power. In this way, by not relying on victimhood, pain, and empathy to enact rights claims, the photozine arguably succeeds in abstracting women from their ‘impaired citizenship’ (Azoulay 2008: 15). The flaws of the law and policy making, which continue to prevail in connection to the issue of abortion, are here bypassed. Forms of governance are suspended, giving way to a different reality in which feminist values are upheld by celebrating and safeguarding women’s bodies and their desires.

Conclusion

Let us conclude with a final image from Marea verde. Through the lens of feminism, the Argentine Congress and the sky around it are now tainted in green, imprinted with the word ‘derecho’ (‘right’) (Figure 22). In the feminist consciousness, our world looks green. It is a world in which the green tide has risen to suspend it all, enabling the emergence of a new conviviality. Feminist activism is fuelled on this future, alternative, ideal. On arresting the ugliness of reality to give way to the pre-emptive feminist celebration of its own imagined possibility. As evidenced in Marea verde, the affective affirmations made by feminism entail a key strategy through which the movement is setting out to create political alternatives in Argentina. Works like Marea verde reconcile conviviality, desire, and celebration with the work of activism, mobilising them as sentiments through which the feminist revolution may be achieved. Victimhood and suffering are not negated, but de-emphasised, in order to, in part, materialise the feminist world we want to see. Mobilisations are moments in which the feminist world becomes our world. Feminism is upon us because we need it to be.

Notes:

[1] In 2018, the bill was first voted by the lower chambers of Congress (Diputados) in June, where it was approved, before being finally rejected by the upper chambers of Congress (Senadores) in August.

[2] A gathering of women activists from all around Argentina that has taken place yearly since 1986.

[3] Translations are my own.

[4] See Marta Dillon (2018).

[5] Miriam Lewin and Olga Wornat’s Putas y guerrilleras (2020, first published in 2014) gathers testimonies to exercise a historical revisitation of sexual violence against women during the dictatorship.

[6] Clandestinidad roughly translates to illegality and secrecy. However, there is no exact English translation.

[7 ] This exhibition was developed in 2017. After having been exhibited in numerous locations around the world, the materials were published as a book in 2023 (Laguna & Palmeiro 2023).

[8] This, however, does not mean that feminist collectives did not engage in crude images of suffering during this time. This was the case particularly with gender violence. See for example Verónica Abdala (2018).

[9] The hanger and the parsley plant are instruments with which women might attempt to perform abortions themselves when safe voluntary abortions are penalised by law or unavailable to them.

Figures:

REFERENCES

Abdala, Verónica (2018), ‘Mujeres colgantes en bolsas plásticas: quiénes son las artistas que hicieron la impactante performance en la marcha por Lucía Pérez,’ Clarín, 6 December, http://www.clarin.com/cultura/mujeres-colgantes-bolsas-plasticas-artistas- hicieronimpactante-performance-marcha-lucia-perez_0_3SMgEAkt-.html (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Agamben, Giorgio (2014), ‘What is a Destituent Power?,’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Wakefield, S. (trans), Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 65–74.

Azoulay, Ariella (2008), The Civil Contract of Photography, New York: Zone Books.

Azoulay, Ariella (2012), Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, trans. by Louise Bethlehem, London: Verso.

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1984 [1965]), Rabelais and His World, Iswolsky, H. (trans), Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bergallo, Paola (2014), ‘The Struggle Against Informal Rules on Abortion in Argentina,’ in Cook, R.J., Erdman, J.N., and Dickens, B.M. (eds), Abortion Law in Transnational Perspective, Philadelphia: DE GRUYTER, pp. 143-165.

Borland, Elizabeth & Barbara Sutton (2019), ‘Abortion and Human Rights for Women in Argentina,’ Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 40, No.2, pp. 27-61.

Butler, Judith (2019), ‘Judith Butler en la UNTREF: Activismo y Pensamiento’, Universidad Tres de Febrero. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSZrXUUDLpQ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Campaña Nacional (2018), ‘Hacia la legalización de la Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo. Argumentos para el debate,’ Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal, Seguro y Gratuito, http://www.abortolegal.com.ar/hacia-la-legalizacion-de-la- interrupcion-voluntaria-del-embarazo-argumentos-para-el-debate/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Campaña Nacional (n/d), ‘Quiénes somos,’ Campaña Nacional por el Derecho al Aborto Legal Seguro y Gratuito Web Site, http://www.abortolegal.com.ar/about/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Civale, Cristina (2018), ‘El fotozine Marea verde cerró la Bienal de Fotografía Documental,’ Jaque al Arte. https://jaquealarte.com.ar/el-fotozine-marea-verde-cerro-la- bienal-de-fotografia-documental/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Di Bello, Patrizia and Zamir, Shamoon (2012), ‘Introduction,’ in The Photo Book: From Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond, Di Bello, P., Wilson, C., and Zamir, S. London: Taurus, pp. 1-16.

De Vedia, Mariano (2018), ‘Fuerte crítica de la Iglesia al proyecto que despenaliza el aborto: “No es un derecho, sino un drama”’, La Nación, 8 August, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/2151378-el-aborto-no-es-un-derecho-sino-un-drama-dijo- monsenor-oscar-ojea-en-la-misa-por-la-vida (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Dillon, Marta (2018), ‘El desborde de la marea. Ni Una Menos, el feminismo popular y los pañuelos verdes,’ Taller de Pensamiento, Programa de Artistas UTDT, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, https://vimeo.com/294451059 (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Fortuny, Natalia (2018), ‘La noche más verde: Celeste y rosa,’ Revista Zigurat, http://revistazigurat.com.ar/la-noche-mas-verde/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Fraiman, Wanda (2018), ‘La noche más verde: Niñas de fuego,’ Revista Zigurat, http://revistazigurat.com.ar/la-noche-mas-verde/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Gamarnik, Cora (2013), ‘Imágenes contra la dictadura: La historia de la primera muestra de periodismo gráfico argentino,’ in Blejmar, J., Fortuny, N. and García L.I. (eds), Instantáneas de la memoria: Fotografía y dictadura en Argentina y América Latina, Buenos Aires: Libraria, pp. 69-92.

Laguna, Fernanda & Cecilia Palmeiro (2018), ‘High in the Tide: Press Release’, Campoli Presti Gallery, London, https://cdn.campolipresti.com/uploads/files/Press- release-High-on-the-tide.pdf

Laguna, Fernanda & Cecilia Palmeiro (2023), Mareadas en la marea: Diario íntimo y alocado de una revolución feminista, Buenos Aires: Siglo veintiuno editores.

Laudano, Claudia (2012), ‘Reflexiones en torno a las imágenes fetales en la esfera pública y la noción de “vida” en los discursos contrarios a la legalización del aborto,’ Temas de mujeres – Revista del CEHIM, pp. 57-68.

Lemaitre, Julieta (2014), ‘Catholic Constitutionalism on Sex, Women, and the Beginning of Life,’ in Ed. by R.J. Cook, Erdman, J.N., Dickens, B.M. (eds), Abortion Law in Transnational Perspective Cases and Controversies, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press (Pennsylvania Studies in Human Rights), pp. 239-257.

Lewin, Miriam & Wornat, Olga (2020), Putas y guerrilleras: Crímenes sexuales en los centros clandestinos de detención, Buenos Aires: Planeta.

Manzano, Valeria (2015), ‘Sex, Gender and the Making of the “Enemy Within” in Cold War Argentina’, Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 47, No. 1: pp. 1-29.

Margolin, Tatiana (2007), ‘Abortion as a Human Right,’ Women’s Rights Law Reporter, No. 29, pp. 77-97.

Movimiento de Mujeres Indígenas por el Buen Vivir (2020), ‘Una reflexión desde los territorios: medicina ancestral, aborto y espiritualidad,’ LATFEM, 21 December, https://latfem.org/una-reflexion-desde-los-territorios-medicina-ancestral-aborto-y- espiritualidad/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Ni Una Menos (2018), Amistad política + Inteligencia colectiva. Documentos y Manifiestos 2015/2018, Buenos Aires.

Nijensohn, Malena, ed. (2018), Los feminismos ante el neoliberalismo, Buenos Aires: LATFEM.

Palmeiro, Cecilia (2018), ‘The Latin American Green Tide: Desire and Feminist Transversality,’ Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 561-564.

Palmeiro, Cecilia (2019), ‘Vanguardia feminista. Acciones del colectivo Ni Una Menos 2015- 2019,’ Revista de estudios y políticas de género, No.1: pp. 1-29.

Sedacca, Natalie (2017), ‘Abortion in Latin America in International Perspective: Limitations and Potentials of the Use of Human Rights Law to Challenge Restrictions,’ Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law and Justice, No.32, pp. 109-136.

Sutton, Barbara & Nayla L. Vacarezza, (2020), ‘Abortion Rights in Images: Visual Interventions by Activist Organizations in Argentina,’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 31-757.

Vacarezza, Nayla L. (2012), ‘Política de los afectos, tecnologías de visualización y usos del terror en los discursos de los grupos contrarios a la legalización del aborto,’ Papeles de trabajo, Vol. 6. No. 10, pp. 46-61.

Vacarezza, Nayla L (2018), ‘Perejil, agujas y pastillas. Objetos y afectos en la producción visual a favor de la legalización del aborto en la Argentina,’ in Aborto: Aspectos normativos, jurídicos y discursivos, Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos, pp. 195-212.

Photography

Reclamos de las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, photography, Eduardo Longoni. Argentina: 1981. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cc-wL0eOYg3/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Represión a las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, photography, Eduardo Longoni. Argentina: 1982. Available at: http://www.eduardolongoni.com.ar/ (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Madre e hija de Plaza de Mayo, photography, Adriana Lestido. Argentina: 1982. Available at: http://www.adrianalestido.com.ar/en/madre_hija_plaza_de_mayo.php (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Marea verde, photography, curated by Sub Coop. Argentina: SubCoop and Fundación Infoto, 2018. Published online by Sub Editorial on Issuu. Available at: https://issuu.com/subeditora/docs/marea_verde_fotozine (last accessed 15 September 2023).

Photographers featured on the Marea verde: Agostina Demarchi / Agustina Feaherston / Agustina López / Aisha Maya Bittar / Alana Rodriguez/ Alejandra Malcorra / Ana Mombello / Ana Isla / Anabella Aranda / Analía Cid / Andrea Castaño y Carla Policella / Andrea Ostera / Andrea Raina / Ángela Tettamanti / Angie Milena Espinel / Anita Pouchard Serra / Ayelen Rodriguez / Borde Colectivo / Carla Temporetti / Carolina Cabrera / Carolina Martinez / Carolina Sánchez Vázquez / Cecilia Antón / Cecilia Basterrechea / Cecilia Bethencourt / Celeste Destéfano / Colectivo de fotógrafas Fisgona / Colectivo Fluxus Foto / Colectivo Manifiesto / Colectivo Sado / Colectivo Voces para multiplicarnos / Constanza Lupi / Constanza Niscovolos / Dafne Gentinetta/ Dagna Faidutti / Daiana Martínez / Emiliana Miguelez / Erica Cánepa / Fernanda Leunda / Fernanda Soria / Florencia Castello / Florencia Ferioli / Florencia Martinez Stoessel / Gala Abramovich / Georgina García / Gilda Lorenti / Guadalupe Arriegue / Guadalupe Gómez Verdi, Lisa Franz y Léa Meurice / Helga Mariel Soto / Jimena Aelen / Jimena Chávez / Jose Nicolini / Josefina Baridón / Julia Negri / Julia Russo Martínez / Julia Sbriller / Julieta De Pian / Julieta Dorin / Karen Toro / Lara Otero / Laura Rivas / Liliana Contrera / Lucía Laurent / Ludmila Belizán / Luisa Magdalena / Maia Alcire / Mailen Panichella / Marcela Heiss / Maria Florencia Lencina / María Naveiro / Maria Paula Ávila / Mariana Lanús / Marianella Sabbadini / Mariana Varela / Marina Carniglia / Martina Perosa / Max Varela Jones / Melisa Salvatierra / Melisa Scarella / Natalia Díaz / Natalia Sofía Molina / Nicole Díaz / Noelia Monopoli / Nora Narvaéz / Otra Óptica informe Fotógrafico / Paola Olari Ugrotte / Paula Lobariñas / Rocío Tursi / Romina Elvira / Romina Morua / Ruedaphotos / Sandra Rojo / Sara Jurado / Sofía Martinez Bordone / Sol Atta / Soledad Castro / Soledad Galván / Soledad Ochoa / Valentina Kalinger / Valentina Casuscelli / Vanesa Espinoza / Verónica Cozzi / Victoria Cuomo / Victoria Gesualdi / Virginia Barbagallo / Vivian Ribero / Xoana Villalba.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey