Emotion, Identity & the Dissenting Gaze: Documenting the Self in Early Motherhood

by: Rosie Reed Hillman , October 5, 2023

by: Rosie Reed Hillman , October 5, 2023

In my self-portrait film and photography project Bearing (2021 dir. Rosie Reed Hillman), I explore the experience of emotion and place in early motherhood. The photography comprises colour images taken on a smartphone exhibited in dialogue with black and white 35mm film portraits. These were exhibited alongside the first screening of the film work in my community in Sheffield. Images from the photography series and film are presented throughout this essay.

In exploring early motherhood experience I felt an autoethnographic approach was essential to transparently respond to and research a subject I was immersed and invested in as a new mother myself. Turning the camera on myself and experiencing the anthropological and cinematic gaze meant interrogating the methodology as well as the subject matter. Autoethnography while challenging and arduous as a process, also allowed a deep exploration of emotional knowledge and the process of creating reflexive practice-based research. Using and evaluating autoethnographic methods contributes to the cultivation of feminist documentary as a genre by examining ways of representing women on screen. Autoethnography has also been an important mode of personal reflection and identity-making in the processual nature of becoming a mother.

To contextualise the images I share here, I want to reflect on the complexities of autoethnography, where I have used my own maternal experience as a lens to highlight concerns shared by other women entrenched in early motherhood. I will discuss what insight and value can be found in creating a personal story as a piece of feminist filmmaking. I also write about the challenges in using this approach in terms of vulnerability and personal costs to privacy, acknowledging how these challenges reveal much about barriers that still need to be broken down for women making art and directing films about women’s lives.

A Collective Account

Bearing does not culminate in an emotional ‘money shot’ to convey a message, rather it visualises the emotional in maternal experience through the nuance of the banal and everyday. Inspired by Often During the Day (1978) by filmmaker Joanna Davis, and the photography of Jo Spence (1988 & 1991), my work examines the minutiae of women’s domestic habits and routines in the home (after Davis) and explores and critiques the genre of domestic photography (after Spence). Bearing contributes to a growing critical mass of mother artists who are increasing the visibility of women’s daily lives through unflinching, fresh storytelling on screen and in photography, poetry, and other art forms. For example, photographic artist Arpita Shah’s Nalini (ongoing, UK) explores motherhood over three generations in her family, crossing three continents. Karolina Cwik’s raw and uncompromising images of domestic life with her children Don’t Look at Me (2021), and Susan Bright’s Home Truths: Photography and Motherhood (2013) have similarities to the photographs made as part of Bearing. Margaret Mitchell’s photographic essays Family (1994) and In This Place (2016-17) also document motherhood over a more extended period of time, a personal account of the artist’s sister and her children living on a housing estate in Scotland. Mitchell’s images echo the work of photographer Sally Mann (1992), who is known for the confronting fine art photographs of her children growing up in rural America. Both photographers address not only the mundanity of domestic life but convey the emplaced experience of motherhood and childhood through their striking portraiture. Immediate Family (Mann, 1992) is an important work exploring how ‘notions of public and private are negotiated through photography’ (Parsons 2008). These negotiations and concerns resonate with the images I made for Bearing.

Over the six-year life of my project, artist responses and documents of the authentic experience of contemporary motherhood also emerged. Bearing is a voice that joins with others, part of what I see as a collective account; women narrating the ways in which they are stretched, discounted, excluded, and made emotionally and corporeally raw by the birth and care of their children. As a new mum I discovered the new poetry and memoir of motherhood: Liz Berry (The Republic of Motherhood, 2018); Holly McNish (Nobody Told Me, 2016); Rachel Bower (Moon Milk, 2018), to name just three. These collections have emerged as a trend in publishing over the last few years and their commentaries on the corporeal and gritty realities of motherhood is backgrounded by the work of those such as Adrienne Rich. Rich set the bar high in the 1970s for searing writing on how motherhood really is. Running concurrently with the new ‘poets of motherhood’ has been the work of visual artists such as Natalie Loveless (Maternal Ecologies, 2012), Lenka Clayton (Artists Residency in Motherhood 2016) and Irene Lusztig (The Worry Box Project, 2011), who attend to themes of motherhood in ways similar to their poetic counterparts.

These works are part of what Loveless describes as the ‘new maternalisms:’ contemporary feminist art that critically responds to the maternal in a way that has not been seen since the 1970s, in the ground breaking work of those such as Mary Kelly’s Postpartum Document (1977) (Loveless 2012: 8).

Bearing

Domestic photography and home videos in the 21st century are not found in a shoebox on top of the wardrobe, but rather on a smartphone and stored in the ‘cloud.’ Documentation of domestic life and children’s’ milestones are ubiquitous features of social media, as are mother blogs, websites such as Mumsnet, and Facebook groups which document every flavour and niche of parenting. Bearing brings together responses that move from pictures on the smartphone, to 35mm portraiture, to moving image; a collected tapestry of images in varying degrees of polish, edit, and clarity in their storytelling.

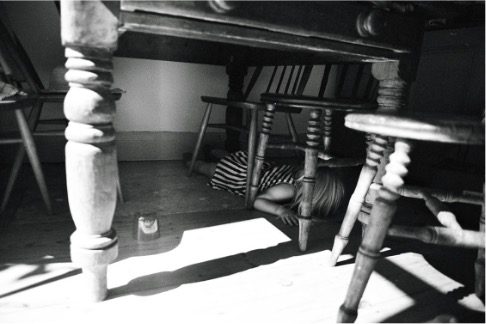

The images in Bearing act performatively, where I see my daughter as a figure representing an every-child, and my presence behind the camera perceived as co-creator of the images with her. The story or meaning found within the image is both personal and ambiguous. For example, in works such as Break (2017) I explore the domestic space in motherhood as a site of claustrophobia and loneliness as well as of refuge and play.

Fig. 1: Break (2017).

Fig. 1: Break (2017).

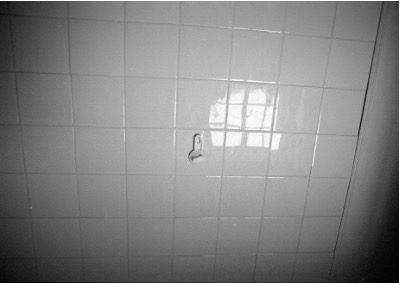

Fig. 2: Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 2: Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 3. Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 3. Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 4: Bike, Pens, Rice Cake (2018).

Fig. 4: Bike, Pens, Rice Cake (2018).

In understanding the state of modern motherhood, visual documents help break down oppressive tropes of the ‘perfect mother’ and promote an understanding of the unseen nature of much of women’s unrecognised domestic work. Bearing has evolved and exists for me, serving in different ways: as a collection of personal artefacts, data from my doctoral research fieldwork, images for recollection and reflection, and as a story or even performance. I believe the collected film, photography and sound can be read as ‘sensory texts’ (Pink 2009: 44). Images and films from fieldwork can contain resonances that invoke emotion in ways that words alone do not. As Sarah Pink explains:

[the footage or photographs] imply a much more direct resonance, a re-gaining of ones’ past experience and a re-touching of relationships, textures and emotions (Pink 2009: 145).

I used sound, moving image, photographic stills, and walking as independent practices to document my experience of early motherhood. My approaches were haptic documentations of experiences and moments with whichever medium was most appropriate to use for a response at that time, be that of corporeal, emotional, social or cognitive mother experience. I took photographs and filmed the detritus of the domestic sphere. I structured the film around vignettes of recurring interactions or acts, labours of mothering. These vignettes were juxtaposed with snatched moments where I was alone without my daughter: in the car, washing up; as well as times I took time out to be in the world without her: surfing, wild swimming, shopping.

Fig. 5: Film still from Bearing (2021). [attempting a wild swim while daughter is with her Dad].

Fig. 5: Film still from Bearing (2021). [attempting a wild swim while daughter is with her Dad].

Vignettes document me and my daughter getting ready to leave the house, a motif repeated three times throughout the film. In the first scene, my daughter is aged 18 months, then two and a half, and in the final sequence, she is four and a half years old. I wanted to highlight the culmination of activities and the everyday drama that makes up the transition between public and private place as it plays out between mother-child. I knew from other mothers that leaving the house was a uniquely frustrating and often complex set of actions and communications. They characterised and exemplified much about the role of contemporary motherhood and the collection of invisible tasks and labours involved in banal daily activity.

Fig. 6: Film still from Bearing ‘leaving the house 1’ (2021).

Fig. 6: Film still from Bearing ‘leaving the house 1’ (2021).

Fig. 7: Film still from Bearing ‘leaving the house 2’ (2021).

Fig. 7: Film still from Bearing ‘leaving the house 2’ (2021).

Fig. 8. Film still from Bearing ‘leaving the house 3’ (2021).

In examining this seemingly unremarkable activity over a period of time, we discover how many individual acts and labours it comprises. Scrutinising this everyday act of mothering, I wanted to demonstrate how ‘private’ family life or intimate acts at home are the context for the ways women (and the children they care for) encounter and experience ‘public’ life and the landscape outside of the house. Despite its ordinariness, leaving the house tells us a lot about maternal experience: the complexities of entering the public arena and the nature of citizenship as a mother. Building on the work of feminist geographers Kate Boyer and Justin Spinney (2016) who researched mother-child assemblages in public places, Bearing is an autoethnographic, creative response that builds on the themes in their original work. In Why are we leaving, where shall we go? the liminal space of leaving to go out is captured: the car being packed, a shoe to be put on.

Fig. 9: Why are we leaving, where shall we go (2016).

Fig. 9: Why are we leaving, where shall we go (2016).

Everyday: The Process of Creative & Maternal Recollecting

Social culture’s fiction of motherhood is one that Adrienne Rich addresses in ‘Of Woman Born’ (1972), an autoethnography which revolutionarily reframed motherhood as ‘patriarchal institution.’ Expressing an embryonic flavour of the killjoy manifesto formed decades later by Sara Ahmed (2017), Rich uses her memoir-thesis, containing reflections on diary entries from when her three children were babies, to outline the state of motherhood and the ways in which it curtails and enslaves women. Still alarmingly relevant in 2022, she politicises the oppressive socio-cultural expectations of mothers’ identity, behaviour and role. Rich also reflects on the conflict of identity of the mother as artist and how her main body of work as a poet does not focus on motherhood:

Once in a while someone used to ask me, ‘Don’t you ever write poems about your children?’ … For me, poetry was where I lived as no-one’s mother, where I existed as myself. (Rich 1972: 31)

How I wished I had heeded Rich’s words when embarking on my own project! With my doctoral research and Bearing complete, I find myself writing again about my motherhood experience in order to contribute to publications such as this one, as well as submitting to film festivals. My experience and its documenting have become a commodity for building my academic and artistic career. This often sits very uncomfortably and has hindered my confidence in putting the work out. Returning to the work for journal papers, film festivals, and as an intrinsic part of my ‘research profile’ is vexed and is a cost of the autoethnographic approach. This approach is a gendered one where women writers and artists self-excavate and mine their experiences in order to bring authenticity and attention to themes and issues affecting women more broadly (Sampson et al 2008). Vulnerability is the currency of the cultural and political climate where sharing and working through things publicly draws praise for bravery and strength. However, there is also skepticism within the academy about the empirical value of personal accounts. There is also the risk of derision for self-indulgent oversharing, and consequently damaging one’s professional legitimacy by being publicly vulnerable (Elke & Carpenter 2015). The emotion work involved in autoethnograhic art or research therefore makes it complex to deliver due to the potential for it to be both personally and professionally taxing (Haynes 2011). Yet by increasing the number of such accounts there is the opportunity to normalise and integrate emotional knowledge and emotional data as valid, moreover essential avenues of social research (Behar 1996).

Documenting the self, while disrupting the power dynamics of the authorial eye, which has traditionally othered experience, also has implications in terms of the extent to which work in the public domain is intersectional. I acknowledge my privileged experience as a white woman and recognise that race, class and sexuality strongly intersect with the experience of motherhood. Of particular focus as outcomes from Bearing as a piece of practice research, are issues of visibility and agency in motherhood, and race is a significant factor that I do not address. I believe further research, testimony and visual ethnography by and from black women would be an important contribution to the findings and themes raised here. Indeed, research and visual autoethnography from mothers across a range of backgrounds, including those across differences in socioeconomic background, sexuality, and routes into motherhood (for example, adoptive mothers), are needed to continue the debate and raise momentum for social change. These contributions are also needed to fill the gaping holes in film and media representations of women’s everyday lives beyond white women’s experience.

In approaching the personal filmmaking process, I have found Sara Ahmed’s visionary writing endlessly useful, particularly her polemic Living a Feminist Life (2017), which describes the idea of a feminist killjoy following her blog of the same name. Ahmed integrates the work of feminist scholars, writers and artists over the last few decades into a coherent arsenal to comprehend the extent and pervasiveness of men’s violence and women’s inequality in contemporary life. She uses these debates and thinking to strengthen her own fierce manifesto for the feminist killjoy, a tool box of philosophical and practical ways to resist and break apart the patriarchal forces that seek to bind and silence women.

Like Ahmed’s killjoy tool box, observing the growing body of work that other mother artists are producing has given me the impetus to continue with my own. Seeing the work as part of this collective account feels important, and sharing my life less a foolish act of vulnerability or oversharing. In understanding women’s corporeal, subjective and emotional experiences in ever more voracious, luminous and visceral ways, it is also more possible to clearly understand how women come up against obstacles or ‘brick walls’ as Ahmed describes them (2017: 148). If people can understand women’s lives more broadly and more deeply, then there is a greater chance of empathy and awareness of the things that are impeding equality, both visible and invisible, and an opportunity to break down those walls that some never encounter.

If walls are how some bodies are stopped, walls are what you do not encounter when you are not stopped; when you pass through. Again what is hardest for some does not exist for others (Ahmed 2017: 148).

Working through the process of making this visual autoethnography by articulating the experience and the ‘brick walls’ I have come up against highlights how both form and content can be vexed obstacles to move through in realising autoethnographic work. (Ahmed 2017: 147). I have been emboldened to make a piece of personal work following in the tradition of feminist artists and writers such as Audre Lorde, who have made an examination of their own experience a political expression. Lorde articulates the validity of explaining life and identity through feeling and emotion in her essay Poetry Is Not a Luxury:

As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring of ideas… feelings were meant to kneel to thought, as women were meant to kneel to men. But women have survived. (Lorde 1984: 26-28)

As in feminist writing, privileging feelings in feminist documentary as an important site of knowledge, allows comment on broader social themes.

Fig. 10: Escape Route (2016).

Fig. 10: Escape Route (2016).

Fig. 11: Outside (2015).

Fig. 11: Outside (2015).

In an interview with Adrienne Rich in the same collection of essays, Lorde states: ‘communicating deep feeling in linear, solid blocks of print felt arcane, a method beyond me’ (1984: 78). She discusses how she has trusted her haptic, emotional way of thinking and describes cultivating this thinking as central to realising her poetry’s identity. Lorde also states how important these ‘emotional sentences’ are, especially in a world that seeks to dismiss and discredit feeling (1984: 78). Lorde argues that women use this skill for ‘courage and strength’ in living within and overturning oppressive systems and relationships. In paying attention to our feelings, dreams and the ‘poems’ we make from them, Lorde states:

This is not idle fantasy, but a disciplined attention to the true nature of ‘it feels right to me. (1977 in Lorde 1984: 26)

Images I have complied for the photo series and film work in Bearing have been realised similarly haptically, with feeling at their root. Images such as Escape Route and Outside are reflective moments within the series that narrate feelings around motherhood that were hard to capture or tell in other ways. Reading Lorde’s assessment of her creative process gave me strength to recognise the potential power in emotion-led and autobiographical art. Using this approach to art practice as research has, however, required a further leap of faith.

Fig. 12: Lidl (2018).

Fig. 12: Lidl (2018).

It took some time for me to be satisfied that documenting the everyday would be ‘enough’ to communicate the multiple socio-political factors that affect the contemporary maternal experience. Initially, it was a challenge to find a way through the images I had collected and make sense of them thematically, emotionally and politically. When I began the project, I was a mother to a 15-month-old and when I finished writing up my doctorate, my daughter was 7. I made these creative works in the thick of my experience of early motherhood, and the process of making, researching and writing reflexively fed back into my understanding of the experience itself. Over the course of iteratively making work that focused on the everyday and paying attention to the emotional in my images, I grew more confident that this focus was an important one. By using nuance and observation of some overlooked details and activities of motherhood I was able to draw attention to the cumulative pressure caused by repeated mundane tasks, juggling of multiple roles and the mental load women experience every day as mothers.

I have felt strongly that the images and film work I have made should speak for themselves, and so have been reluctant to analyse these visual reflections further. This was partly because the task of revisiting parts of my maternal experience was often a painful one.

Feelings of depression, boredom and isolation, and becoming a single parent were the realities of new motherhood that I was not expecting (alongside the joy, sleepless nights and boundless love, which I was). I wanted to visualise and contribute a more authentic picture of motherhood, as seen in images such as Burning things on my own. Focusing on these themes through research of other mother artists’ work and scrutinising the darker side of my story of being and becoming a mother resulted in me avoiding collating and finishing the film and photography work. In the middle of the project, I felt I had fallen into an impossible rabbit hole of living the banality of early motherhood while also trying to conjure up innovative and exciting film methods for examining it. I feared sharing the work publicly because I felt the subject matter was not universal or exciting enough (feedback on early edits queried how the subject would be relevant or of interest to an audience beyond new parents). I worried that my directing was not innovative enough or did not offer the audience enough ‘spill your guts’ emotion to understand the film’s intended themes exploring the realities of early motherhood.

Fig. 13: Burning things on my own (2017).

Fig. 13: Burning things on my own (2017).

The reality of translating counter narratives and ideas onto the screen through observation of my daily life at home with my daughter was an ongoing challenge. At the beginning of the project, I intended to make the work speak to these political critiques of motherhood more overtly, but as time went on, I struggled to be both a mother and document motherhood in a way that I felt was good or creative enough.

The editing process changed this and allowed me to explore ways to reflect on and convey emotional experience without playing to convention and constructing the emotional breakdown ‘reveal’ scene I felt I was missing. Instead, I used the edit to create a nuanced set of images that were personal and specific to me, while leaving enough space and ambiguity to enable the audience to put themselves in mine and my daughter’s place. Emotionality was conveyed through the dialogue of vignettes alongside each other and repetition and examination of the mundane and everyday, rather than the outwardly dramatic or ‘emotional’.

I discovered that collating the work was a becoming through the work itself. For Rosi Braidotti becoming is understanding identity and subjectivity to be intrinsically fluid, an ongoing process of transformation (2002). In editing and exhibiting Bearing I found that both photography and film pieces made earlier in the project had been either overlooked, totally discounted as not good enough, or deemed irrelevant. Not only did the process of bringing these together in a meaningful way uncover the message and intention of the images when viewed as a whole body of work, on a personal level it contributed to processing the identity shift of becoming a mother (Boyer 2018: 18). Visually seeing my experience of motherhood: reinterpreting, remembering, and resolving what had gone before had an emotionally informative impact on me. When I originally recorded the images in Bearing, I objectified or externalised my experience; I then re-performed this through the collating and collecting of images, and finally, in the screening and exhibiting of the finished work, I more fully owned and integrated my identity as a mother and an artist.

The fluid nature of finding ones maternal identity as a ‘movement towards the unknown’ chimes with Ahmed’s writing on the formation of queer identities. (Ahmed 2006 in Boyer 2018: 23). The sense of otherness women feel after birth, the new experiencing of the postnatal body, the new finding of one’s sense of self, and one’s new place in the physical world. There are also maternal performativities which women are socially obliged to engage in and enact in relation to gendered expectations of motherhood: during pregnancy, from the day their baby is born, and over a lifetime of being a mother (Butler 1990). ‘Doing motherhood’ within (and even without) the parameters, these norms can be repetitive, constraining, boring, complex, and often an oppressive experience. Bearing, in chorus with the collective mother artist account of motherhood mentioned above, draws attention to these performativities and this sense of otherness.

The images have served as prompts to memories—emotional and corporeal—which have stories behind them. In recollecting through visual ethnography, I have ‘converted private into public meanings’ (Jackson 2001). Using both memories and corporeal and emotional responses to reviewing the images I have made, Bearing was an act of performativity that helped to make sense of my early motherhood experience. In collating and editing, I remember how I felt at the time of the image, and how I feel and understand that memory in its recollection. This process of remembering is notable in the project’s smartphone photography, where the content of these images is nearly always a smiling baby or positive memory. I took these images as a mother, recording my baby’s milestones. In recalling the image afterwards, despite the seemingly cute or happy subject matter, many times I recall in reality having had a challenging day, feeling lonely or exhausted—an experience not represented in the image. I included these smartphone images in Bearing to highlight this juxtaposition, and to expose the fiction of contemporary culture’s curated images of motherhood on social media. These photos are how we create our identities online. They have constructed and sustained unattainable narratives of the ‘ideal’ version of perfect motherhood and mothering. While more recently counter narratives to these have emerged on social media, the convention of the cute baby or kid pictures prevail. (Das 2019).

Fig. 14: Play with me Mummy (2018).

Fig. 14: Play with me Mummy (2018).

In contrast to the smartphone snaps I took as a mother recording memories, 35mm portraits were created with my artist hat on. These were taken with a similar immediacy and not staged or choreographed. As seen in works such as Play with me Mummy where the image was realised with a considered focus on making a piece of commentary and with a critical lens. In making the moving image work in Bearing, there was a mixture of immediacy and planned sequences. This combination enabled further reflexivity through editing and the discussion of filmed sequences. Bringing autoethnographic moving images together into a finished piece of work involved working out what each sequence intended to represent or narrate at the time of making, how I remembered the event now, and how we would use the scene for the purposes of the finished film.

A reading of the idea of the killjoy is that there can also be empowerment, euphoria, solidarity and wonder in the living of and being a mother. This satisfaction might be found in a re-writing of the identity of ‘mother’ as one who is prepared to disrupt expectations about how that identity acts and behaves. The experience of being a killjoy also describes how mothers can find themselves disrupting social space or expectations of their gender by existing in spaces that do not seek to accommodate them. Motherhood is an experience lived in the context of a hegemonic discourse with normative expectations on how maternal bodies and identities should be enacted (see feminist scholars on motherhood: Ruddick 1989; O’Reilly 2006 & 2014; Baraitser 1989; Benn 1999). This makes living a life beyond these parameters ‘work.’ Women alive to the politics of this work in relation to their gender inevitably interrupt, correct, complain and exist in ways that make us feminist killjoys (Ahmed 2017: 2). The process of maternal becoming therefore entails both structural and intimate feminist battles to assert ourselves as part of coming to know ourselves as mothers.

Filmmaking as a Feminist Killjoy

The opportunity to explore the witnessing of my own life experience has turned out to be a privilege, despite the challenges. Like anthropologist Ruth Behar, I believe that transparency in detailing the ‘feeling’ reasons for approaching a research topic or theme can create authentic ethnographic accounts that include emotional responses. To deny or reject the emotional world of the researcher is to lose something in the ‘contextual and experiential understandings’ (Behar 1996: 943) that ethnography strives to capture.

My memories associated with early motherhood are hard to pin down. Responses to my own images and film work have helped me to unpack these memories. In early motherhood I found myself at turns mesmerised, choking with laughter, in despair on the bathroom floor, then disassociating at the eye-watering, repetitious boredom of it all. An experience intensely visual but drenched, triggered and coloured by other senses of sound, smell and touch in equal measures, intersected by and inseparable from an ever-changing field of emotions.

Bearing visualises how the role of mother involves encountering ‘patriarchal obstacles’ to living within normality as an equal and included citizen (Benn 1999). As a feminist killjoy, one might disrupt patriarchy with complaints that it is nearly impossible for women to ‘have it all.’ We can disrupt the curated image of motherhood by breaking rank with the smug- marrieds and the kids-are-my-world narratives, by offering multiple narratives of how motherhood is. We can disrupt the hard edges of the ‘child-free’ movement by daring to complain about a situation we got ourselves into and chose while still celebrating and adoring our children. A mother feminist killjoy can disrupt mental health narratives by declaring that having a child, becoming a mother, can be an experience of madness (see Kristeva 2005). We can argue that this madness is not because of something wrong with us but with the structural impossibilities women live under. It is because of philosophically oppressive ideals about women’s roles, identities, and bodies prescribed to us. To be a mother is to encounter patriarchy through both its oppressive structural realities and in its most insidious and unassuming forms.

Making the everyday and the domestic sphere a subject worthy of film, art, literature—as many women artists are now doing—gives motherhood and the component activities and complex identities that comprise it weight and importance. I consider the female gaze in my work to be a dissenting gaze. Bringing the everyday to the spectacle and ‘seriousness’ of the cinema, gallery and poetry collection forces our culture to look and see, even if they choose to look away. Bringing women’s experience into the public domain in this way takes up cultural space and asks questions of norms that are so ingrained we don’t see them anymore. Perhaps we can call this feminist killjoy filmmaking.

Fig. 15: Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 15: Film still from Bearing (2021).

Fig. 16: Second Birthday, Red Shoes (2015).

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living a Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University.

Bariaitser, Lisa (2009), Maternal Encounters, London: Routledge

Behar, Ruth (1996), The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology that Breaks Your Heart, Beacon Press.

Benn, Melissa (1998), Madonna and Child: Towards a New Politics of Motherhood, London: Cape.

Berry, Liz (2018), The Republic of Motherhood, New York: Random House.

Bower, Rachel (2018), Moon Milk, Scarborough: Valley Press.

Boyer, Kate & Justin Spinney (2016), ‘Motherhood, Mobility and Materiality: Material Entanglements, Journey-making and the Process of “Becoming Mother”’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 34, No. 6, pp. 1113–1131.

Boyer, Kate (2018), Spaces and Politics of Motherhood, Rowman & Littlefield.

Braidotti, Rosi (2002), Metamorphoses: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming, John Wiley & Sons.

Bright, Susan (2013), Motherlode: Photography, Motherhood and Representation [Exhibition catalogue] to ‘Home Truths: Photography, Identity and Motherhood’, London: The Photographers Gallery.

Butler, Judith (1990), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York: Routledge.

Clayton, Lenka (2016- ongoing), Artist Residency in Motherhood, [Digital media], http://www.artistresidencyinmotherhood.com/ (last accessed 20 September 2023).

Cwik, Karolina (2021), Don’t Look at Me [Photographs] Czech Republic

Das, Ranjana (2019), Early Motherhood in Digital Societies: Ideals, Anxieties and Ties of the Perinatal, New York: Routledge

Emerald, Elke & Lorelei Carpenter (2015), ‘Vulnerability and Emotions in Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 741-750.

Haynes, Kathryn (2011), ‘Tensions in (Re)presenting the Self in Reflexive Uutoethnographical Research’, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 134-149.

Jackson, Michael (2002), The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity, Museum Tusculanum Press.

Kelly, Mary (1977), Postpartum Document, Tate Collection.

Kristeva, Julia (2005), Motherhood Today, http://www.kristeva.fr/motherhood.html (last accessed 20 September 2023).

Lorde, Audre (1977), Poetry is Not a Luxury, https://makinglearning.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/poetry-is-not-a-luxury-audre-lorde.pdf (last accessed 20 September 2023).

Lorde, Audre (2020), Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Penguin Classics.

Lusztig (2011), The Worry Box Project [Online]. Available: http://worryboxproject.net (last accessed 20 September 2023).

Mann, Sally (1992), Immediate Family, Aperture.

McNish, Holly (2016), Nobody Told Me: Poetry and Parenthood, London: Blackfriars.

Mitchell, Margaret (1994), Family in Passage, Glasgow: Bluecoat Press.

Mitchell, Margaret (2016-17), In This Place in Passage, Glasgow: Bluecoat Press.

New Maternalisms: Redux Curated by Natalie S. Loveless, FAB Gallery 1-1 Fine Arts Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 12 May 12-4 June, 2016.

Often During the Day (1978), dir. J. Davis, Four Corners Film Archive, London. O’Reilly, Andrea, (2010), Twenty-first Century Motherhood: Experience, Identity, Policy, Agency, New York: Columbia University Press.

Parsons, Sarah (2008), ‘Public/Private Tensions in the Photography of Sally Mann’, History of Photography, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 123–136.

Pink, Sarah (2015), Doing Sensory Ethnography, London: Sage.

Rich, Adrienne (1977), Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, London: Virago.

Ruddick, Sara (1980), ‘Maternal Thinking’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2. p. 342.

Sampson, Helen, Michael Bloor & Ben Fincham (2008), ‘A Price Worth Paying? Considering the Cost of Reflexive Research Methods and the Influence of Feminist Ways of Doing’, Sociology, Vol. 42, No. 5, pp.919-933.

Shah, Arpita (ongoing), Nalini [Photographs], Bradford: Impressions Gallery.

Speed, Ewan, Joanna Moncrieff & Mark Rapley (2014), De-medicalizing Misery II: Society, Politics and the Mental Health Industry, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Spence, Jo (1986), Putting Myself in the Picture, London: Camden Press.

Spence, Jo & Patricia Holland (eds) (1991), Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography, Worcester: Billing & Sons.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey