Daisy P. on the Cliff: Seeing Through Different Eyes

by: Adèle Cassigneul , May 23, 2019

by: Adèle Cassigneul , May 23, 2019

A Dream-like Intermediary Space

When she happens to come upon a new lovable face, up bubble vivid hues and images: a sense emerges.

Daisy Patton has been a compulsive collector of discarded family photographs since 2014. She is a daring colourist whose expressive overpaintings magnify photography–scanning and enlarging the original images to make them as close to life-size as possible–and transgress media boundaries in order to portray becoming. Black and white photographs metamorphose into intense ornate paintings, their palimpsestic liminality questioning memory, identity and form. Her series started in 2014 and it is entitled Forgetting is so long.

Fragments of the blown-up photos survive under the coats of paint and pierce the veils of colour; haunting presences linger in a transitional space and float in a virtual territory akin to that of dreams. ‘I think this might be a tie to my younger self painting my dreams’, Daisy tells me (Patton 2018c). Her paintings evoke the magnetic appeal of dreams, their fantastic illusions and boundless abilities to refashion the invisible déjà-vu. As such, Patton paints a mythical space in which the realism of photographic indexicality becomes imaginary and fantasy becomes reality (Pontalis 2013). Daisy’s attractive images experiment with surreal in-betweenness and float freely like alluring visual memories that triumph over disappearance and regain life (Pontalis 1990). Their oneiric charm sublimates loss and forgetfulness in order to articulate a new intermedial language and outline a passageway that channels transmission and creativity. Her pictures are caught in the ‘trajectory from photography to painting’ (Foucault 2014: 28) and delineate a productive space. Defacement, covering and ornamentation help to construct a visionary frame wherein potentiality prevails, and through which Daisy can assert her radical artistic gesture.

Indeed, there is an essential subversion in this process of negotiation and transgression of media boundaries, in the act of estrangement by which family portraits are concealed under effervescent pop colours. Beyond recognition, faces are turned into strangely playful masks and bodies are dressed again and come to resemble paper dolls. These uncanny mutations and mutants become marvellous in these revived surroundings.

‘My sourced images have pierced me’, Daisy explains (Patton 2016). Her dream-images are born of piercing details that spark a series of poignant metamorphoses and accidents which both prick and bruise her (to paraphrase Barthes’s definition of the punctum (1981: 27)). The transfigurative process through which she works relies on desire, instinctual associations and ‘subconscious impulses’ (Patton 2016); it bears the mark of Freudian transformation of thoughts and emotions into visual images. ‘I like to let my first reactions to an image, or maybe reactions that come after being still and allowing things to be quiet, be the ones that guide how they are painted’ (Patton 2018c), she says. Daisy secretly connects to her models’ concealed dreams and seeks out other possible or fantasy lives for them. By masking, concealing, or occluding parts of bodies and faces, she plays hide and seek with the subject’s quizzical gaze in order to enhance their inherent mystery.

Unrevealing mute faces.

Alluring beings.

Silently beckoning.

Inviting reverie.

Naturally, intermediality enhances surreality. Photography can be used as a tool to deconstruct established pictorial practices (Krauss 1999: 294). The transformative power of painterly translation defamiliarises the visual field so that dissimulation eventually generates a poignant coming-into-being; it is perhaps this manifestation of essence which Jean-Luc Nancy analyses as a remainder/reminder of presence (2000: 54). Likewise, the portrait here stands as the metamorphic interpretation of a stark anonymity; or as Foucault might term it a ‘beautiful hermaphrodite of instantaneous photograph and painted canvas, the androgyne image’ (Foucault 2014: 23). I contend, then, that Daisy is queering pictorial conventions.

Fantastic Generation(s)

What I admire about Foucault’s metaphor here is that it imbricates difficulties of categorisation, aesthetic hybridity and gender indeterminacy, whilst acknowledging the irreverential complexity all these entail (Hawker 2004: 267). It also underlines the fantastic intermedial circulation of images that started around 1860-1880 [1] as ‘a new freedom of transposition, displacement and transformation, of resemblance and dissimulation, of reproduction, duplication and trickery of effect’ (Foucault 2014: 23-4). I regard Daisy Patton to be walking in the steps of those innovative generations but, above all, I view her as a true heiress to the long-discarded experimental artwork practised in aristocratic Victorian drawing rooms.

Daisy (re)generates generations and in doing so, she taps into a vernacular of feminine lineage. Contrary to Duane Michals, whose painted tintypes hark back to the High Modernist tradition of Cubism and James Joyce (Robertson 2013), or Gerhard Richter, whose smeared family snapshots re-enact surrealist automatism to a level of abstraction that is bereft of informational value (Laxton 2012: 792-4), her refigured hybrids rework the inventive craftsmanship of long-forgotten, sometimes anonymous, Victorian ladies. These women collected and assembled factual domestic photographs and combined them with fictional photocollage composition in order to expand ‘the limitations of photography, to incorporate fantasy, dreamscapes, whimsy, and humour’ (Siegel 2009: 32).

Artistic genre and gender matter.

They signify.

They tell different stories.

The indignity suffered by Victorian photocollage (compared to, say, canonised male Surrealist or Dadaist photomontage) was two-fold: it worked on mechanically reproduced images (the medium so distinctly lacking in artistic aura as famously outlined by Walter Benjamin) and it was ‘feminine’ in a society that was defined strictly along lines of gender thus ensuring that women’s artistic endeavours were hardly ever recognised (here we could invoke, for instance, Coventry Patmore’s 1854 The Angel in the House on perfect womanhood–a trope that Virginia Woolf expressed immense difficulty in killing off). Yet as Daisy underlines, at that time, as well as for decades afterwards, ‘women were the holders and caretakers of memory (a role I have taken up myself)’ (Patton 2018a). Women acted as the family archivist. In appropriating and personalising studio portraits, Victorian ladies at once subjected photography to their own idiosyncratic vision (thus twisting their first purport as class-bound normative social icons) and became the fantastic story-tellers of reconfigured flirtatious family (hi)stories.

I have argued that Daisy (re)generates generations, but she also (pro)creates them. That is, her photo-paintings actually represent and enact (pro)creation. In her images I see generations of women (indeed, they take up 72 portraits of 104 to date): mothers, daughters, sisters, and granddaughters. Women dead or alive, celebrated or mourned are viscerally present in her work. I see various existential moments coded by conventionally gendered postures and visual mores. I see abandoned domestic photographs that have remained undiscovered for years in thrift shops, flea markets or on eBay (Patton 2016), just waiting to be noticed. Waiting to be seen differently and thus repurposed, recreated, and recuperated into another artistic loop that might work to reform cultural constructions of images, memory and femininity.

‘If we don’t have names, who are we?’ (Levy 2018: 11)

‘Forgetting is so long’ is a line from Pablo Neruda’s 1924 poem, ‘Tonight I can write’, which suggests that oblivion is an active force which survives and lingers. As original photographic faces still show under the portraits’ painterly surface, Daisy’s transfigured images highlight the persisting presence of unknown, mainly female individuals. In the folds of the photo-pictorial palimpsest, the altered heart of what-has-been still ardently beats, ‘between a mechanical reproduction of the spectre and an appropriation that is so alive, so interiorizing, so assimilating of the inheritance and of the ‘spirit of the past’ that it is none other than the life of forgetting, life as forgetting itself’ (Derrida 1994: 136). Enduring forgetfulness.

In Spectres of Marx, Derrida assumes that oblivion is a moment of ‘living appropriation’ (2010: 137). The life of forgetting is caught between the disappearance or erasure of memories and the legacy of a spirit of the past; thus he insists that we must acknowledge loss for what it is–‘keep loss as loss’ (Derrida 2010: 19)–in order to preserve its surviving traces. ‘One keeps the archive of ‘some thing’ (of someone as some thing) which took place once and is lost, that one keeps as such, as the unkept, in short, a sort of cenotaph: an empty tomb’ (2010: 19). His words find a correlate in Daisy’s own artistic intentions, ‘Not alive but not quite dead, each person’s newly imagined and altered portrait straddles the lines between memory, identity, and death. They are monuments to the forgotten’ (Patton 2014). As I watch Daisy’s collection of nameless faces, I confront an atypical type of archive – that of complete disappearance. ‘[Family photographs] show a mother, a child, a past self, full of in-jokes and the mundane meaningful only to a select few. But divorced from their origins, these emotion-ridden images become unknowable and lost in translation’ (Patton 2014). This accumulation of obscure, unrecorded lives sets me surreptitiously wondering: who do we remember? who gets to decide who is worthy of being salvaged from oblivion? who will give us back our names in order to restore our identities and our histories? because, if we don’t have names, who are we?

In 1929, Woolf anxiously asked: ‘But of our mothers, our grandmothers, our great-grandmothers, what remains? … We know nothing of them except their names and a date of their marriages and the number of children they bore’ (1979: 44). Compiling miscellaneous images from every part of the world, Daisy cannot retrieve her models’ names. Sometimes scribbles stand as cyphers at the back of photographs, which only serves to emphasise further their enigmatic qualities. Daisy thus confronts ignorance and impenetrable darkness. Ferreting in ‘those almost unlit corridors of history where the figures of generations of women are dimly, so fitfully perceived’ (Woolf 1979: 44), she defaces photographs to bring out better the inner self, the intimate mystery of the person portrayed. She shocks them into being as the ‘painting allows the person to come back from death for a moment’ (Boyd 2018). Her colours, patterns and ornaments are the torches she holds firm in her hand to explore lost or ignored lives and share their ineffable secrets as so many gifts. A dream of the dead redivivus.

Enacting the ‘regenerating reviviscence of the past’ (Derrida 1994: 136), Daisy shuns nostalgia to stretch time out. She slows down images (Batchen 2004: 25) with the full knowledge that there is no specific memory to be rebuilt, nor recollections to recapture. ‘I am pulling [the photographs] out of their time-frame into a different state of time–perhaps a limbo or super-present state’ (Patton 2018b). Time is thus loosened up, galvanized, set out of joint. Freed from any recognizable context, the images stand as nameless orphans–indeed, they remain unnamed, the series is considered untitled–floating through anachronic temporalities, their futures being directly born out of their undistinguished pasts. The artist’s pictorial gesture updates forgotten presences so that their absence is suddenly brought closer to us (Nancy 2000: 64). ‘With Forgetting is so long, my aim is to actually de-historicise the individuals from the past to make them present’ (Patton 2018a). Haunting voices return.

‘She had the oddest sense of being herself invisible; unseen; unknown’ (Woolf 1981: 10-11).

‘Becoming woman, being no more’ (Amhed 2017: 44).

‘All these infinitely obscure lives remain to be recorded’ (Woolf 1977: 97).

‘Feminist work is memory work’ (Ahmed 2017: 22).

I read Daisy’s bewitching demiurgic gesture as fundamentally humanist (she restores life) and feminist (she primarily restores and rebuilds women’s lives). If portraiture acts as the interface between interiority and exteriority (Nancy 2000: 28), then Daisy’s images expose her models’ inner selves as mediated by her own personal experience. The artist herself recognises this:

I do tend to gravitate to women’s portraits, keen observation! I think women’s lives are often forgotten or ignored most frequently. Women are seen as decorative objects for art but not as living, breathing subjects who are worthy of study. I see a lot of complexity in their images, recognizing how gender roles may have restricted them from being full individuals and how that feeling of being trapped might have felt. I tend to choose people with whom I can have empathy with, and I think it’s easier to find this with women (Patton 2018a).

When her eyes happen to meet a woman’s photographed gaze, an empathetic bond secretly weaves itself into the canvas and initiates undisclosed narratives. Daisy is a storyteller ‘drawn to histories that are erased or hidden in dominant culture’ (Anderson Ranch Art Center, 2017). She amplifies untold ineffable stories to generate knowledge, understanding and recognition. She urges us to see what has remained hidden or ignored.

The Signifying Line of Beauty

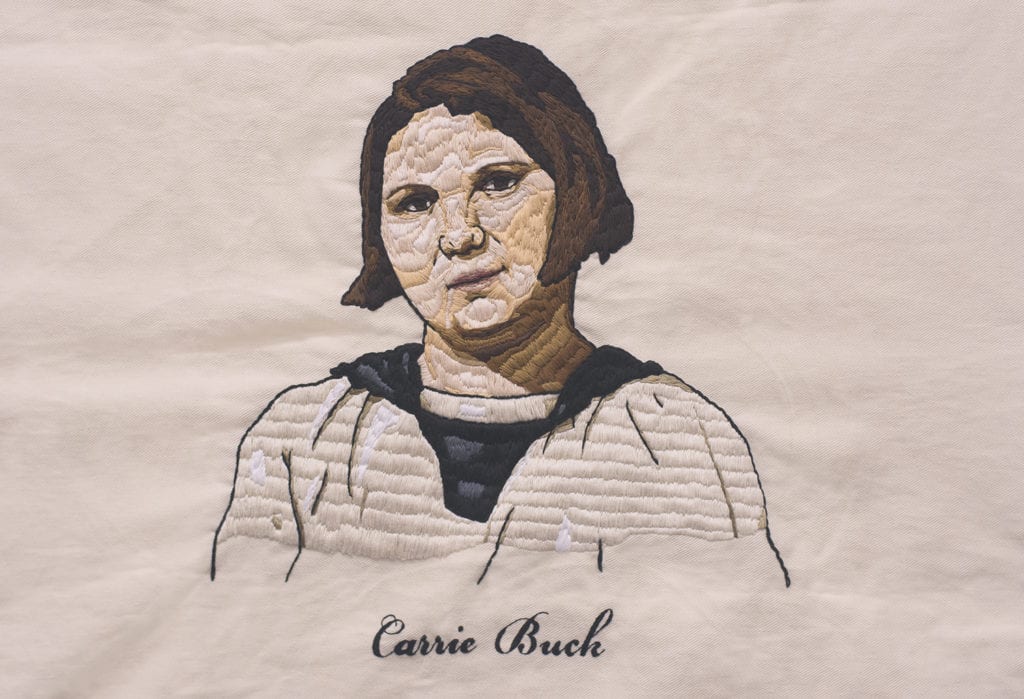

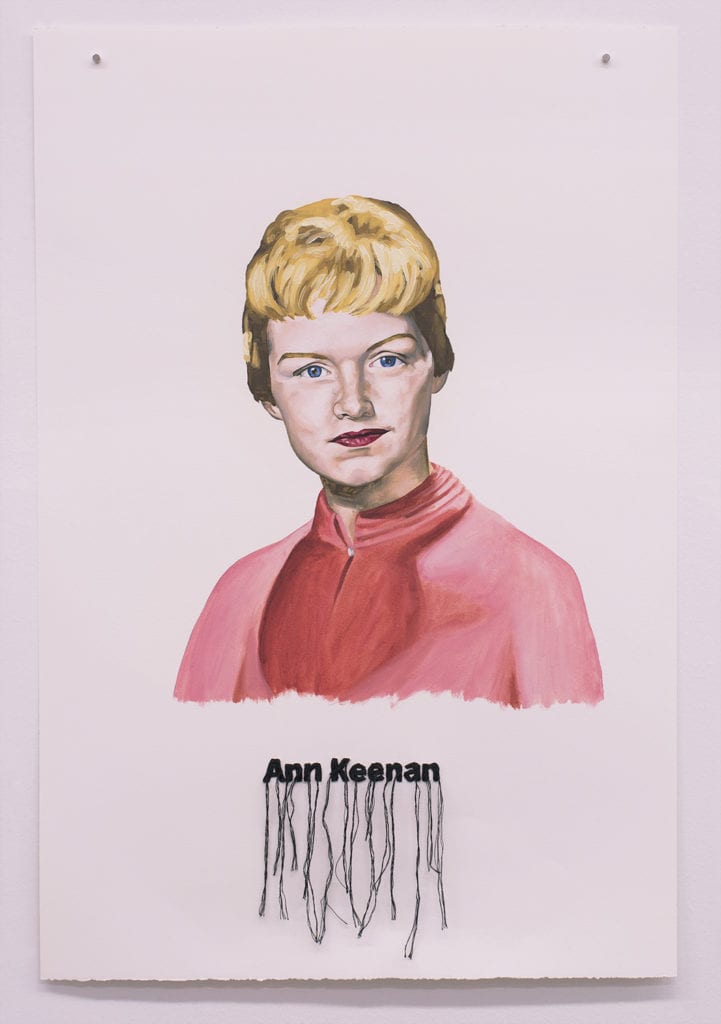

And Daisy is an activist. Her artwork is also resolutely social work. On top of her Forgetting series, she has launched two side projects that are not meant to exist in the art market, ‘100% of the proceeds are donated to reproductive justice organisations’ (Patton 2018d). Would you be lonely without me? represents women who died of botched abortions. Women who were considered delinquents, outlaws, shameful and corrupt creatures (as Annie Ernaux (2001) might have it). Daisy paints their portraits and embroiders their names underneath, leaving sharply cut threads in front which connect the portrait to its companion still-untitled series on forced sterilisation; this is a collaborative embroidery project that portrays those who were considered ‘a burden on the rest’ (excerpt from the American Eugenics Society travelling exhibits, the 1920s) and directs attention to erased histories. In doing so, it raises awareness on reproductive rights (or lack thereof) and has a deliberate political bent at its core. ‘My focus is so often on women because, to me, representation and recognition of humanity is a political act’, asserts the artist (Patton 2018d), who belongs to a generation of young female creators purposefully exposing patriarchal and sexist histories–I think of Spanish visual artist Laia Abril’s powerful A History of Misogyny the first chapter of which entitled, ‘On Abortion’, was first presented at Les Rencontres d’Arles (France) in 2016. [2]

Daisy embroiders names into her work to document visually marginalised histories and to return these women’s humanity. In her art, threads are physically representative of undervalued domestic activities; these threads represent lives, even if those lives have been curtailed. Her project is feminist precisely because the citation of names entails building a feminist memory and archive (Ahmed 2017: 15 -17). By centering her work on intense, strong and confident women, she feels empowered as a female artist. This resonates with what poet Sophie Collins underlines in her work; namely that: ‘There is also–still a shock and a delight in seeing female experiences named, and both the establishment of women’s networks and the naming of these experiences contribute to the consciousness-raising that can combat the silence and the dampening of the self that pervade trauma’ (2017: 31).

I find it difficult to pick up examples for description, to indulge in a little ekphrasis, because if I choose a single image, I separate it from its wider context; in doing this the image would lose its auratic and symbolic radiance. It would stand as an unfinished sentence. Daisy’s work functions as a coherent, living body that works against evisceration into bits and pieces. The images are connected and communicate as a series: and in doing so, they invent their own cumulative visual language. This has to do with the colourful patterns and winding wreaths which bind them together and guide our gaze from one picture to the other. But it also pertains to the assembled feminine faces that shape this inclusive community. To the extent that when I confront these ordinary women, I recognise our shared commonality. When looking into their eyes and scanning their faces and bodies, I too become part of Daisy’s fantasied extended family. And I am invited to witness a few newly enlivened marriages or funerals, an intimate collective gathering or an affectionate moment between a couple. I am called upon to belong.

When I attend closely to Daisy’s images, I hear a voice echo. It is the voice of the painter Lily Briscoe in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. She too is named after a flower, but I’ve secretly renamed her ‘Lily B. on the cliff’ as she spends her days painting on the lawn overlooking the bay and inhabiting a liminal space between the Ramsay household and the boundless horizon beyond. Lily is a pioneer. She has established herself in-between, at the precarious yet creative interface between social life and solipsistic isolation. She works hard to hold onto her artistic vision. Lily is a role model. Yet regularly, the voice of society, enforcing its effective retrograde prejudices, slyly whispers in her ears ‘Women can’t paint, women can’t write’, and she is led to believe that her work ‘would never be seen, never be hung even’ (Woolf 1992: 54). To the Lighthouse was published in 1927.

Ninety years later, Daisy wrote a short piece called ‘Ginger Rogers’ in which she reflects on her own experience as an art student and woman artist and lists the pervasive symptoms of a gender-biased world where sexist behaviours still prevail unquestioned:

My words are ignored by men until they are spoken by my husband–or another man, she says.

Masculinity is prized. Women who embrace it are still undervalued. Femininity is unserious, girly, ‘not art’, she adds.

And she goes on:

To be a woman artist is to be accustomed to walking into galleries and museums to see your gender displayed naked as objects, but seldom as creators. I will not yield, she declares. I am an artist (Patton 2017).

Daisy P. is painting on the cliff and is thwarting the ‘male glance’, which always grades aesthetics on a ‘gendered curve’ (Loofbourow 2018). She has endorsed devalued artistic forms–vernacular photography claiming artistic legitimacy (Bourdieu 1990: 110) [3], decorative and ornate patterns, which are deemed feminine and are overlooked–and she has transcended them by finding her own artistic language. I’ll dare to call it, after Hogarth, the line of beauty. In his Analysis of Beauty (1753), the latter analysed serpentine lines as expressive of liveliness and movement, as active signifiers that amplify the density and the complexity of the painting’s composition and call for the viewer’s attention.

Conventionally, painterly or decorative ornaments are considered inessential or insignificant and are consequently dismissed as superficial and trivial. Lacking restraint, their extravagant baroque allure is said to bar access to unfathomable depths. Decorative patterns are thus condemned as aesthetically and even morally undesirable. And as it happens, photographs too are flat, ‘platitudinous in the true sense of the word’ writes Barthes. ‘I cannot penetrate, cannot reach into the Photograph. I can only sweep it with my glance, like a smooth surface’ (1981: 106). It arrests interpretation. We are thus told that ornaments are superficial and photos are evidential. ‘Rather than investigate or discover, we point and classify’ (Loofbourow 2018). Come on! move along, there’s nothing interesting to see here! And the same old story starts all over again (think of those Victorian ladies and their outrageously ornamental photo-paintings).

But Daisy’s paintings usher us into thought and feeling and ask that we dwell here in contemplation. Disclosing the spectacle of an apparition (Rouillé 1982: 132), the family photographs act as enticing ‘access points’ (Patton 2018d); at the intersection of the colourful and black-and-white planes, they open a secret door leading to hidden wonderlands.

The ornamental profusion of Daisy’s images work to extrapolate the 19th century wallpaper designs she selects from their repetitive framework. Her work dismantles rigid sequences, abolishes geometry and opposes flatness to unleash pulsating vivifying energy. Her work possesses a playful quality that wards off morbid stasis. ‘I’m re-wilding them by allowing movement’, the artist points out (Boyd 2018). Brought to the forefront of her images in this manner, the floral motifs appeal to my haptic gaze, its tactile sensuality. Colours modulate and shine so that the adorned surface of the photograph allows my ‘eye to function like the sense of touch’ (Deleuze 2003: 122). Guided by the optical play entailed by the spatializing energy of varying shades, I am made to interact with the image and to sink into its unfolded visual field, shedding veil after veil of colours. My body becomes intertwined with the framed visible field and my eye, as Daisy’s before me, ‘envelops, palpates, espouses the visible things’ (Merleau-Ponty 1968: 133).

***

Confronting Daisy’s work has been quite an intellectual and sensory adventure. It has meant time travelling from the early days of photography to our connected Instagram age to engage in a phenomenological experience that entails pondering over time, mortality and memory. Daisy’s dialectical images of the past get revived the moment I set eyes on them: the photographs seem to come furtively to life, offering themselves to my understanding and immediately dissolving back into the canvas, partially buried under proliferating patterns (Benjamin 2000). Their liminality also performs some uncanny reversal of vision, what Merleau-Ponty calls the ‘reversibility of the seeing and the visible’ (1968: 154). Because the photographed models looked straight at the camera, they now look me in the eyes. Indeed, as I watch it the image watches me and, as it is looking at me, it sends me back to my own personal relation to the passing of time. It summons intimate family memories. It brings home something fundamentally human linked to remembrance, care and story-telling.

But even further, as I face Daisy’s images, I find myself experiencing alterity, that is watching the Other in his or her spectralised version of themselves. I am making the acquaintance of ghosts that set me wondering about those that photography virtually brings back from the dead and those who remain caught in limbo. What about those that remain invisible? those who never had their picture taken? Daisy’s archive of disappearance documents at once the proliferation of portraits that underlines the ways in which photography democratised people’s access to self-representation, thus the possibility to be remembered, and the blatant absence of all those that remain unrepresented. Forgetting is so long then implicitly anthologises its own lapses and speaks to those shadow images of the forever missing. Are the images lacking because some people did not have the means to take up amateur photography and thus remain irrevocably unseen, washed away by the passage of time? Or is it because some families actually keep and cherish memorabilia while others get rid of them and consequently make them public by abandoning them to the market? And this sends us back to our own photographic practices. What will happen with digital images? How do we keep them except in a fragile virtual and often ephemeral archive on computers or mobile phones? Might we not in time be confronted with another kind of loss? the loss of individual and common memory that is amnesia?

I wish to conclude on what Barthes calls the’ writerly’ text, which challenges the reader’s position as a subject and empowers them to take an active role in the construction of meaning. Refusing to turn them into receivers of a fixed, pre-determined reading (that is consumers of a product), ‘the writerly text is ourselves writing’ (1975: 5). Reading, we subjectively write the text anew. Imagining becomes yet another mode of thinking and this is exactly what Daisy’s images do to and for me. Observing becomes another way of understanding and working things out. Not that her pictures are myself painting, as Barthes would say, but they prick me, seduce me, and challenge me. They encourage me to feel, to dream, to reflect. They set me in motion.

The reflexive dimension of Forgetting is so long, which clearly appears in the way Daisy foregrounds her media (both enlarged photography and painting), encompasses questions of reception and interpretation. The generous transparency of Daisy’s painterly act shows in her pictures’ intermediality. As Daisy remarks:

I do not sketch (beyond colour mockups of paintings) anymore, but I do collect a lot of photos and other visual materials that make their way into paintings. Fashion images, pics that someone has posted on Instagram, my own photographs of flowers, old masters paintings that are unfinished, etc. (Patton 2018c)

The Victorian frenzied circulation of images is still operative. In fact, it never ceased to be. And Daisy’s work actualizes this frantic life of images, their fluidity, their enriching hybridity. This is why it is so intimately engaged with the world artistically, politically, ethically and, by extension, why it asks me to be conscious of the world creatively and poetically. This is why Daisy’s images are so moving.

The entire collection of Daisy Patton’s work can be viewed on her website: http://daisypatton.com

Notes

[1] See the joined history of painting and photography in Siegel, Easton, Kosinski, de Font-Reaulx, and Poivert.

[2] On 6 September 2018, Daisy posted the following text on Instagram: ‘A souvenir from today’s powerful talk at the Annual Women’s Leadership Council by Dafna Michealson Jenet about her experience with losing a much-wanted baby and having to get an abortion after he passed. Read her book ‘Peanut’s Legacy’; this luncheon was in support of @prochoiceamerica and a stark reminder of how critical complete access to #reproductivehealth and #reproductiverights are for all of us to be fully free. If you haven’t already called your senators demanding they stop this farce of SCOTUS hearing and vote no, do it now! We will all be affected for at least a generation and it’s crucial you make your voice heard.’ This captions a poster showing a young woman wearing a ‘1973’ t-shirt who stands before a background print saying in red bold letters ‘FIGHT FOR FREEDOM’. It comes in the heated American political context when ultra-conservative Judge Brett Kavanaugh is undergoing Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

[3] See also Chalfen (1987) and Chéroux (2013).

REFERENCES

Abril, Laia (2018), On Abortion and the Repercussions of Lack of Access, Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living a Feminist Life, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Anderson Ranch Arts Center (2017), ‘Forgetting is so Longby Daisy Patton’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPwXWeexSRo (last accessed 21 August 2018)

Barthes, Roland (1975), S/Z, London: Cape.

Barthes, Roland (1981), Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill & Wang.

Batchen, Geoffrey (2004), Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance, Amsterdam & New York: Van Gogh Museum/Princeton Architectural Press.

Benjamin, Walter (2000), ‘Sur le concept d’histoire’, Œuvre III, Paris : Gallimard, pp. 427-43.

Bourdieu, Pierre et al. (1990), Photography. A Middle-brow Art, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Boyd, Kealey (2018), ‘Reanimating Women from Found Photographs’, Hyperallergic, 27 July 2018, https://hyperallergic.com/450604/reanimating-women-from-found-photographs/ (last accessed 28 July 2018).

Chalfen, Richard (1987), Snapshot Versions of Life, Bowling Green: BGSUPP.

Chéroux, Clément (2013), Vernaculaires. Essais d’histoire de la photographie, Cherbourg: LePointduJour.

Collins, Sophie (2017), Small White Monkeys. On self-expression, Self-help and Shame, London: Book Works.

Deleuze, Gilles (2003), Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, London & New York: Continuum.

Derrida, Jacques (1994), Specters of Marx, New York & London: Routledge.

Derrida, Jacques (2010), Copy, Archive, Signature. A Conversation on Photography, Stanford: SUP.

Easton, Elizabeth (ed.) (2011), Snapshot. Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ernaux, Annie (2001), Happening, New York: Seven Stories Press.

de Font-Réaulx, Dominique (2012), Peinture et photographie. Les Enjeux d’une rencontre 1839-1914, Paris: Flammarion.

Foucault, Michel (2014), La peinture photogénique, Paris: Le point du jour.

Hawker, Rosemary (2009), ‘Idiom Post-medium: Richter Painting Photography’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 263-80.

Kosinski, Dorothy (1999), The Artist and the Camera. Degas to Picasso, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Krauss, Rosalind (1999), ‘Reinventing the Medium’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 289-305.

Laxton, Susan (2012), ‘As Photography: Mechanicity, Contingency, and Other-Determination in Gerhard Richter’s Overpainted Snapshots’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 776-795.

Levy, Deborah (2018), The Cost of Living, London: Hamish Hamilton.

Loofbourow, Lili (2018), ‘The Male Glance’, The Virginia Quarterly Review, No 94, Spring 2018, https://www.vqronline.org/essays-articles/2018/03/male-glance (last accessed 2 September 2018)

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1968), The Visible and the Invisible, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Nancy, Jean-Luc (2000), Le Regard du portrait, Paris: Galilée.

Patton, Daisy (2014), ‘Forgetting is so long. Artist statement’, http://daisypatton.com/galleries/forgetting-is-so-long-2014-2015/ (last accessed 31 August 2018).

Patton, Daisy (2016), ‘Forgetting is so long’, Backroom, 1 July 2016, http://backroomcaracas.com/escritura-expandida/forgetting-is-so-long/ (last accessed 29 August 2018).

Patton, Daisy (2017), ‘Ginger Rogers’, http://daisypatton.com/ginger-rogers/ (last accessed 11 August 2018).

Patton, Daisy (2018a), ‘Re: The Life of Forgetting: Reproduction Rights’, email to A. Cassigneul, 30 April 2018.

Patton, Daisy (2018b), ‘Re: Playing with Pictures’, email to A. Cassigneul, 1 June 2018.

Patton, Daisy (2018c), ‘Re: Lives of the obscure’, email to A. Cassigneul, 22 August 2018.

Patton, Daisy (2018d), ‘Re: Embroidery’, email to A. Cassigneul, 4 September 2018.

Poivert, Michel (2017), Peintres photographes: de Degas à Hockney, Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod.

Pontalis, J-B (1990), ‘L’attrait du rêve’, La Force d’attraction. Trois essais de psychanalyse, Paris: Seuil, pp. 9-56.

Pontalis, J-B (2013 [1977]), Entre le rêve et la douleur, Paris: Gallimard.

Robertson, Rebecca (2013), ‘Duane Michals: Fighting Against Photography’, ARTnews, 29 July 2013, http://www.artnews.com/2013/07/29/duane-michals-fighting-against-photography/ (last accessed 30 August 2018).

Rouillé, André (1982), L’Empire de la photographie. Photographie et pouvoir bourgeois 1839-1870, Paris: Le Sycomore.

Siegel, Elizabeth (2009), Playing With Pictures. The Art of Victorian Photocollage, New Haven & London: The Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press.

Woolf, Virginia (1977), A Room of One’s Own, London: Grafton.

Woolf, Virginia (1979), Women and Writing, New York: Harcourt.

Woolf, Virginia (1981), Mrs Dalloway, New York: Harcourt.

Woolf, Virginia (2000), To the Lighthouse, London: Penguin.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey