Biography of a Story

by: Phillip Crymble , December 13, 2021

by: Phillip Crymble , December 13, 2021

When first published in 1948, Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ caused a public outcry. A parable that concludes, shockingly, as an innocent woman is stoned to death by her community, Jackson’s story, for many readers, was deeply unsettling. The New Yorker, where it appeared, received hundreds of letters from subscribers demanding an explanation. As Ruth Franklin mentions in Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (2016), Kip Orr, who was charged with writing responses to these letters, did so ‘with the magazine’s standard formulation … ‘It seems to us that Miss Jackson’s story can be interpreted in half a dozen different ways,’ he wrote to reader after reader. ‘It’s just a fable’. (quoted in Franklin 235) That ‘The Lottery’ is so open to interpretation is precisely what made it appealing to me, but the more I learned about the circumstances in which the story was written, the more I came to see it, first and foremost, as a covertly defiant feminist text.

In ‘Biography of a Story'(1960), which was published posthumously, Jackson recounts the hours leading up to the moment she sat down to write what would become her most notorious tale:

The idea had come to me while I was pushing my daughter up the hill in her stroller—it was, as I say, a warm morning, and the hill was steep, and beside my daughter the stroller held the day’s groceries — and perhaps the effort of that last fifty yards up the hill put an edge to the story; at any rate, I had the idea fairly clearly in my mind when I put my daughter in her playpen and the frozen vegetables in the refrigerator … (Jackson 1960: 787)

What Jackson omits here is that, at the time, she was pregnant with her third child, and that her first, a Kindergarten student, was at home with her in the afternoons. As Franklin states in her biography, “‘The Lottery’ ‘depicts a world in which women, clad in ‘faded house dresses,’ are defined entirely by their families”, and this depiction was consistent with ‘the world in which Jackson lived, the world of American women in the late 1940s, who were controlled by men in myriad ways large and small: financial, professional, sexual’. (236) While Jackson’s husband, an autocrat and serial philanderer, spent his days teaching at Bennington College, she took care of all the household responsibilities, and in writing ‘The Lottery’ she was able to vent her frustrations and analogically indict the patriarchal power structures that governed her life.

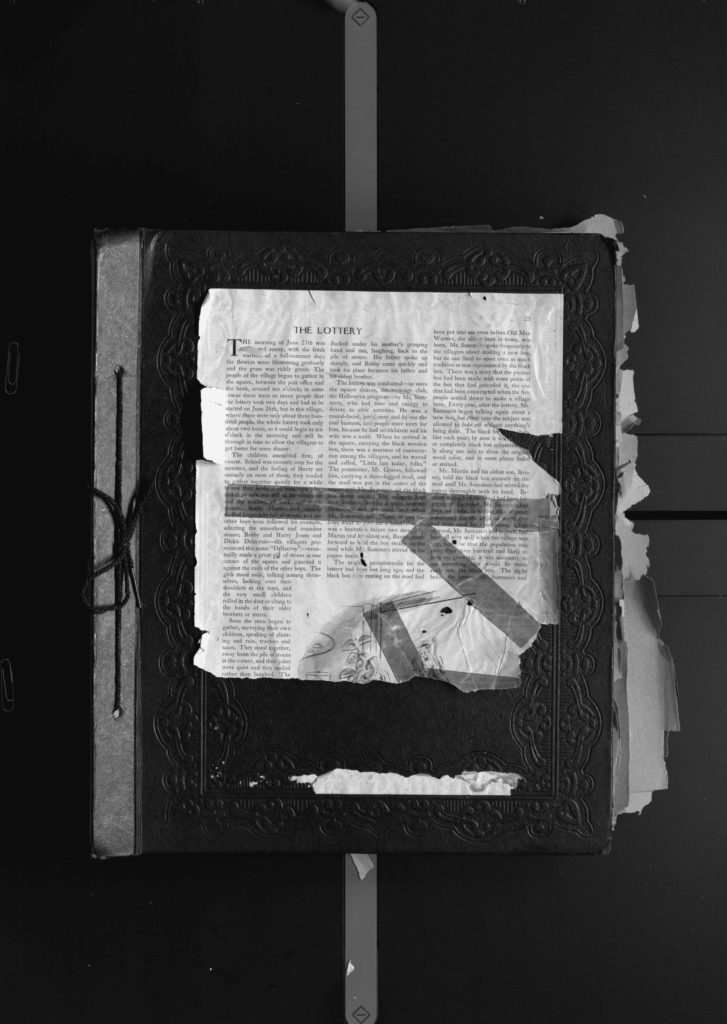

In approaching my poem (which borrows its title from Jackson’s memoir), the challenge, I felt, was to create a tribute, in verse, that like ‘The Lottery’, communicated its message through analogy. That Jackson kept many of the righteous and accusatory letters reacting to her story in an oversized scrapbook struck me as an ideal point of entry, as this often-aggressive correspondence documents the conservatism and latent misogyny that was so widespread in post-war American society. Fascinated by the occult since she first encountered James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890), Jackson, as stated in her biographical information sheet for Farrar, Straus, was ‘an authority on witchcraft and magic … and is perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch’. (quoted in Franklin 217) Struck by the idea that Jackson’s scrapbook could be seen as a book of spells, or ‘clavicle of alchemy’, I began exploring the possibilities that this analogy afforded. And in likening the scrapbook to ‘an overwritten codex’ I hoped to draw attention to the history of palimpsestic subterfuge in women’s writing practices, practices that, like her predecessors, Jackson used to strategically conceal a counter-hegemonic message beneath the surface of her narrative.

***

Biography of a Story

for Shirley Jackson

Shelved among the thirteen miles of boxes in the LOC —

protected now from light and migrant acids — stray lignins

and humidity — the outsized leather scrapbook in your archive

waits in air-conditioned darkness like an overwritten codex

or a clavicle of alchemy. On the cover, ripped and incomplete —

the folio you tore from The New Yorker, scissored, held in place

by glue — the strips of old adhesive tape applied to mend it

frail and ossified — as yellow as a witch’s teeth. Inside, affixed

with staples, paste, and rubber-based epoxies — all those letters

of displeasure, condemnation and abuse. “Outrageous,” “grim

and gruesome,” “a perversion of democracy.” Subscribers

in their hundreds asked if what you wrote was true. As if

they understood that blame and female sacrifice were things

they thought they recognized — things they thought they knew.

This poem originally appeared in Arc Poetry.

REFERENCES

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. Liveright, 2016.

Oates, Joyce Carol, editor. Shirley Jackson: Novels and Stories. Library of America, 2010.

Thanks to Ruth Franklin for providing the image of Jackson’s scrapbook, which appeared in her 2016 biography.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey