#FuckWhitePeople: Dean Hutton’s ‘Decolonial Gesture’ as Critical Digital Citizenship

by: Tessa Lewin , June 25, 2022

by: Tessa Lewin , June 25, 2022

Introduction

This article explores the political challenge posed by queer artist and photographer Dean Hutton’s 2016 #FuckWhitePeople (#FWP) to the fantasy of post-apartheid South Africa as an inclusive ‘Rainbow’ nation. #FWP was a performance artwork, developed by Hutton during their MA degree at Michaelis (the fine art school at the University of Cape Town), that developed in response to a photograph they took of the fallist [1] Zama Mthuzi wearing a t-shirt with the words ‘Fuck White People’ inscribed on the back, and ‘Being Black is Shit’ on the front, at a #FeesMustFall protest at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg in 2016. Hutton’s piece comprised several ‘live’ performances and the on-going documentation of responses to the work, many of which took the form of online and social media posts. I focus here primarily on the incarnation of the work as a ‘selfie booth’ at The Art of Disruptions exhibition at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town from June-October 2016 and pay particular attention to the ‘paratexts’ of this artwork, the materials supporting and augmenting it, that are facilitated by the project’s web extensions. (Genette 1987; Smith & Watson 2012) I offer an appreciative reading of Hutton’s work, that is at the same time cognisant of the mixed reception of #FWP, a reception indicative of the complexities of South Africa’s fragmented publics, and of the limits of political participation in this context.

I understand Hutton’s artistic practice to be what Chantal Mouffe terms ‘critical,’ in that it aims to subvert the hegemonic symbolic order of white supremacy (Mouffe 2008: 9). Employing Mouffe’s concept, together with Derek Conrad Murray’s (2015:491) suggestion that the selfie ‘may offer the opportunity for political engagement, radical forms of community building—and most importantly, a forum to produce counter-images that resist erasure and misrepresentation,’ I characterise Hutton’s work both as a mode of ‘critical digital citizenship’ and as a mode of survivorship (Murray 2015). Theresa Senft and Nancy Baym’s (2015) understanding of selfies as relational, and Adi Kuntsman’s (2017) reading of them as an act of citizenship, are also helpful to an understanding of Hutton’s work.

This article draws on fieldwork data from my doctoral research, which examined queer visual activism in contemporary South Africa. Hutton was one of sixteen South African artists that I interviewed during two periods of fieldwork in 2015 and 2016. My fieldwork comprised participant observation and semi-structured in-depth interviews, together with analyses of artists’ visual practice. Nine of the original sixteen interviewees (including Hutton) were also involved in a process of participatory analysis. Here I draw on my interviews with Hutton, their own MA thesis (completed in 2017) and my reading of their work (which I saw at the Iziko National Gallery in Cape Town during my 2016 fieldwork).

Hutton is a critically acclaimed social documentary photographer. In 2016 when this piece was produced, Hutton was based at Michaelis, the University of Cape Town’s fine art school, on its Hiddingh campus. This campus was occupied for almost half of that academic year by Umhlangano, a collective linked to #FeesMustFall that aimed to re-politicise and decolonise the art institution (Gamedze 2017). Hutton was an active member of Umhlangano, and their artwork can be read as a decolonial gesture [2], a ‘doing for and toward the future … the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world’ (Munoz 2009: 1).

The Rainbow Nation

Central to an understanding of Hutton’s work is their offering of a queer utopia as a reparative gesture in the context of the failure of the ‘Rainbow Nation.’ Hutton mobilises their own gender ambiguity to unsettle the stark binaries through which race continues to be framed in the South African context. Their reaching towards this alternative (queer) utopia is a critical response to the way in which the utopia promised by rainbowism has been eroded by the persistence of white supremacy.

The ‘rainbow nation’ was the term used to refer to South Africa after 1994, when apartheid ended, and Nelson Mandela became president. The term was coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to describe a happy and racially diverse nation (Evans, 2010:309). The ‘rainbow’ referred to in this formulation was widely viewed to be not just about racial diversity, or non-racialism, but also about gender and sexuality (Reid 2010 & Munro 2012). It was a national myth used to engender a shared sense of post-apartheid euphoria and cohesion.

Writing in the Mail and Guardian in March 2016, Richard Pithouse—then a political scientist at the University currently known as Rhodes—declared the Rainbow nation dead (Pithouse 2016). Pithouse was echoing sentiments expressed by writer, and commentator Sisonke Msimang (2016), who a week earlier said: ‘[i]t is clear now that the decision to focus on peace as the founding principle of our new democracy was taken at the expense of justice.’ Both comments came in the wake of an incident in February 2016 at the University of the Free State (UFS), where white Afrikaner rugby fans violently and publicly beat non-violent black protestors who interrupted a rugby match (Msimang 2016). Police then intervened, reportedly targeting only the black protestors, not the white rugby fans (Nicolson, 2016). Many would argue that the Rainbow nation was dead long before 2016. Critiques of the concept of the rainbow nation began during the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1996 and continued through the years of Thabo Mbeki’s presidency and state-sanctioned AIDS-denialism, and through increasing state repression during Jacob Zuma’s presidency, which culminated in the Marikana Massacre of 2012. The incident at UFS was one of many that contributed to the erosion of the myth of ‘rainbowism,’ and the politics it represented.

Pumla Gqola writes about one of the ANC’s 1994 election posters—a visual articulation of the idea of a ‘rainbow nation’—which depicts a smiling Mandela, surrounded by a multi-ethnic group of smiling children (Gqola 2015: 1). Gqola argues that this image asks South Africans to gloss over the fact that the children’s different colours represent unequal access to resources, uneven access to power, and different treatment, even in the post-apartheid future to which the image alludes. The image asks South Africans to suspend any anger at racial (and, linked to this, social and economic) injustice, and to work towards a better future for all South Africans (Gqola 2015: 1). As Gqola writes: ‘[i]t requires that we believe a future free of institutionalised white supremacy is possible if we vote ANC … Vote ANC, and all our children will be happy’ (Gqola 2015: 1). The rainbow fantasy offered the promise of utopian equality, but with the persistence of vast structural inequities. This framing offered protection to the existing elite, and for the majority, a deferred hope.

Hutton’s artwork can be read as an active engagement with the Fees Must Fall (#FMF) movement that began in 2015, as a series of protests which came in the wake of the #RhodesMustFall (#RMF) movement. #RMF, was an on-going campaign against institutional racism, which successfully oversaw the removal of a prominent statue of British colonist Cecil John Rhodes from the University of Cape Town campus in April 2015, after weeks of protest. Both #RMF and #FMF were responses to frustration at the slow pace of change in post-apartheid South Africa, in terms of both institutional racism and socio-economic realities. South Africa remains ‘one of the most consistently unequal counties in the world,’ and although there has been a moderate decrease in poverty levels since the end of apartheid in 1994, there has also been a sharp rise in income inequality (Bhorat 2015). The legacy of South Africa’s Natives Land Act of 1913, which stripped most black people of their right to own property (an act then reinforced by the later apartheid legislation) is also still evident, with white South Africans owning 72 percent of the 37 million hectares of land held by individuals (Gumede & Mbatha 2018).

Rekgotsofetse Chikane (2018) argues that the central message of the #RMF movement was that ‘to build a nation, we must break the rainbow,’ quoting writer Panashe Chigumadzi, who describes the rainbow as ‘the fantasy of a ‘colour-blind,’ ‘post-race’ South Africa’ (Chigumadzi 2015). Hutton’s ground-breaking and controversial artwork emerges in this context, and also links to a set of debates about the connections between rainbowism and queerness. Numerous writers mark this connection, in which queer South Africans come to symbolise the nation’s newfound constitutional democracy (Reid, 2010; Munro, 2012). But commentators also suggest that the queer subject, publicly lauded and protected post-1994, is a white, affluent, cis-gendered, gay man (Visser 2013; Tucker 2009; Oswin 2007; Livermon 2012; Stone & Washkansky 2014; Munro 2012). As Jane Bennett has observed, ‘queer no more consists of a rainbow arc than the rest of South Africa’ (2018: 104).

This article draws on Jose Munoz’s Cruising Utopia (2009), Chantal Mouffe’s (2008) understandings of critical art, recent writing on the critical potential of selfies—in particular Murray’s (2015) article—and Jane Bennett’s reflections in ‘Queer/white’ in South Africa: a Troubling Oxymoron (2018). Hutton’s Master’s thesis (2017) articulates their practice as one that uses ‘technology as self-reflection and radical sharing,’ concepts I use to structure my discussion and analysis of their work. Before exploring each of these ideas further, I will introduce Hutton and their artwork in more detail.

Dean Hutton and #FuckWhitePeople

Hutton describes themselves variously as a ‘white,’ ‘trans,’ ‘non-binary,’ ‘genderqueer’ [3] ‘fat’ artist. For 18 years Hutton worked for the national weekly newspaper the Mail and Guardian as a photojournalist. They left photojournalism to become a fine artist, which they found to be less ethically compromising (Hutton, interview in Johannesburg, October 2015). From 2016 to 2017, Hutton was based at Michaelis, the fine art school at the University of Cape Town, where they completed a master’s degree. Hutton’s 2016 #FuckWhitePeople (#FWP) piece, on which this article focuses, formed part of the practical submission for their MA, and the broader project Plan B, A Gathering of Strangers (or This is Not Working).

As already outlined, Hutton’s #FWP piece emerged in response to the events surrounding a photograph they took while documenting a #FMF event in February 2016 at Wits (University of the Witwatersrand), in which a student, Zama Mthunzi, was wearing a self-fashioned t-shirt which read ‘Being black is shit’ on the front, and ‘Fuck white people’ on the back. There were strong reactions both to Hutton’s photograph of Mthunzi (the posting led to a 30-day ban on Facebook), and to Mthunzi’s gesture itself. The University administration instituted disciplinary procedures against Mthunzi, and he was reported to the Human Rights Commission. [4] When Wits students protested the University’s actions against Mthunzi, launching a graffiti campaign which sprayed ‘#fuckwhitepeople’ across campus, the University administration accused these students of forcing them to spend money on graffiti removal that could otherwise have gone towards students’ financial aid. [5] These events, combined with Hutton’s arrival in Cape Town, their shock at how racially segregated it remained, and what they saw as the investment of South African universities in white privilege, prompted Hutton’s early imaginings about their #FWP piece [6] (Hutton 2017).

#FuckWhitePeople began as a performance piece in which ‘Goldendean’ (Hutton’s performance persona) wore a tailored suit made from black and white fabric which read FUCKFUCKFUCK WHITEWHITEWHITE PEOPLEPEOPLEPEOPLE in alternating lines. ‘Goldendean’ appeared in public wearing this suit and distributed cards containing humorous and provocative questions about whiteness. Hutton wore a GoPro camera to document the performance (with participant consent), capture its interactions, and serve as a layer of self-protection (the idea being that the threat of surveillance would temper potential violence). The cards directed people to a website https//fuckwhitepeople.org, which provided viewers with twelve steps to learn to ‘fuck the white in them’ (Hutton, Interview in Cape Town, November 2016). Hutton, describing the performances, observed that they consistently provoked ‘very important conversations with people who had begun to deconstruct their identities as white people’ (Hutton, Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

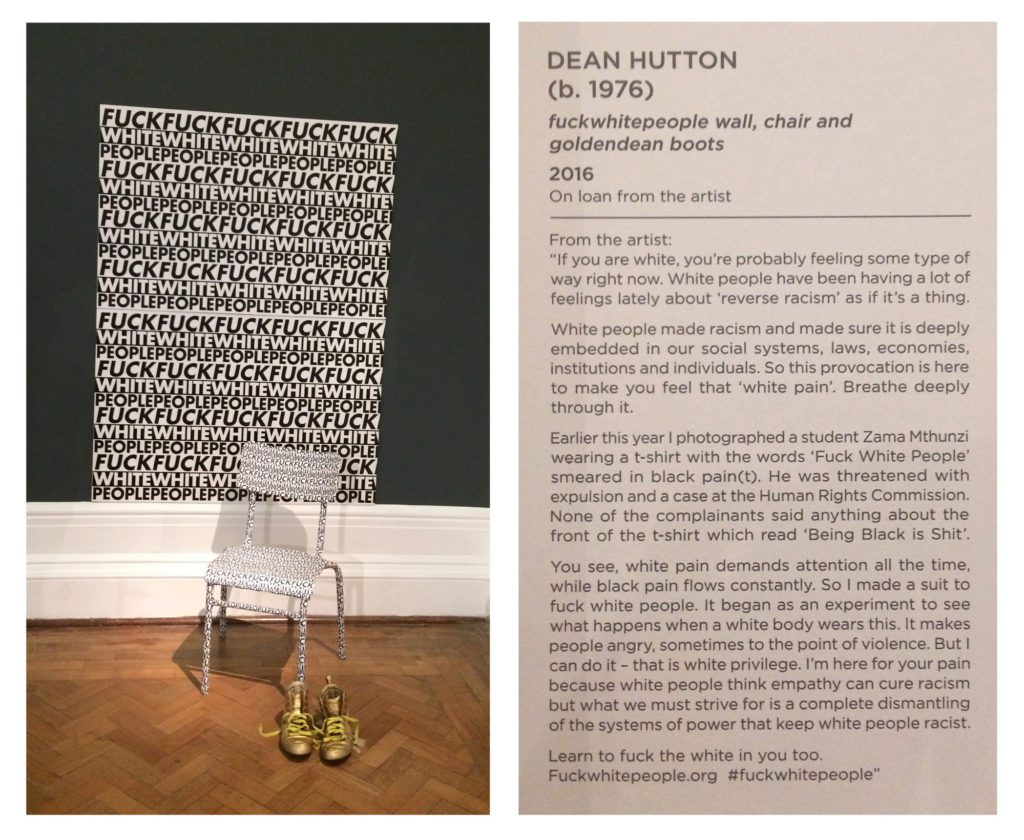

Although Hutton’s work is rooted in public performance, it goes far beyond this in the outputs of their practice. The version of #FuckWhitePeople I focus on in this article was a ‘selfie booth’ installed at the Iziko South African National Gallery as part of the Art of Disruptions exhibition, the gallery’s response to the socio-political climate of the time (2016). The selfie booth comprised two posters, an old school chair wheat-pasted with printed paper, and a pair of worn gold Adidas high tops. The posters and chair were covered very simply in the same black and white design of ‘Goldendean’s’ suit that read FUCKFUCKFUCK WHITEWHITEWHITE PEOPLEPEOPLEPEOPLE in alternating lines (See Fig. 1a). Viewers were encouraged to engage with the piece by photographing themselves in the booth and tweeting the result with the hashtag #fuckwhitepeople. In this version of their piece, Hutton was only present in the written explanation of the work that accompanied it, and through the inclusion of ‘Goldendean’s’ hightops. The selfie booth serves as an extension of Hutton’s performance work, and its online circulation facilitates a further extension.

The choice of ‘Goldendean’ as Hutton’s performance persona merits comment. On a very generic level, the gold suggests value, beauty, and excess. Equally, it signifies something lurid, hyper visible, and queer. In the South African context, gold evokes the mining wealth that so much of the economy was built on, and which has been (for many black South Africans) the source of so much suffering and inequality. Goldendean’s shoes in the context of the gallery display, become the shoes of privilege. Hutton’s symbolic removal of these shoes can be seen as a decolonial gesture that recognises this privilege and chooses to reject it. Goldendean’s gold body then becomes a reminder that this act is only possible as a symbolic gesture. Hutton cannot escape their white (gold) skin.

Love as Political Agency

I understand #FWP as Hutton’s attempt to navigate a particular political moment in a way that affords them both political agency and hope. Munoz’s understanding of queerness as ‘a doing for and towards the future’ (2009: 1) and bell hooks’s (2000) insistence on the importance of seeing love as a verb rather than a noun, are both important to an understanding of Hutton’s project. #FuckWhitePeople is motivated by Hutton’s belief that South Africa needs to radically deconstruct its still-racist social and political institutions if it is to heal from its violent past. It is about asking white South Africans to recognise and acknowledge the privileges still accorded to whiteness in contemporary South Africa. Hutton offers up their queer utopia, as an alternative to the failed utopian imaginary of the rainbowism.

Mouffe describes public space as ‘a battleground on which different hegemonic projects are confronted’ (2008: 9). She regards critical artistic practices, such as Hutton’s, as playing an important role in ‘subverting the dominant hegemony’ (Mouffe 2008:9). Such practices work both to disrupt the smooth appearance of a particular symbolic order (in this case white supremacy) and in so doing, to construct new subjectivities (2008: 13). Hutton’s recognition of whiteness as white supremacy, or a ‘collective racial epistemology with a history of violence against people of color’ (Leonardo 2009: 111), requires them to actively find a way to construct an alternative subjectivity. #FWP can be read as an experimental gesture acknowledging that all white people benefitted from apartheid, and as trying to break what Melissa Steyn terms the ‘ignorance contract’ that allows white supremacy to persist in post-apartheid South Africa (Steyn 2012: 90).

Here Hutton talks about grappling with the dis-ease they experience in their own complicity with hegemonic whiteness, and their desire to escape this:

I have felt this discomfort with this identity my entire life. it’s not something that is new … the real potential of the project is that white people can see a way out of white supremacy. Because it’s like with the history, and it’s like we can’t get caught in the guilt (Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

Many white South Africans routinely disengage from conversations about the politics of race, partly because they can afford to (they remain privileged), and partly because they feel they do not have a right to do so— as Hutton articulates, they ‘get caught in the guilt.’ Race theorists suggest that whiteness has remained largely invisible and unexamined (Dyer 1997 & Steyn 2001). #FWP tries to reveal the hegemonic form of whiteness (white supremacy) as a historical construction (Steyn 2001), and in doing so open up the possibility of its deconstruction. Additionally, Hutton is attempting to denaturalise the connection between their white skin, and whiteness as a ‘ruling class social formation’ (Allen 1994). Hutton sees their work as an act of love, not as in the noun evoked by the myth of the rainbow nation, but as in the verb, the everyday commitment to action espoused by hooks (2000). Making visible and deconstructing this form of whiteness—and its associated privileges—is a task that Hutton argues all white South Africans have a responsibility to tackle.

Having contextualised Hutton’s work, and in particular #FWP, I want to examine the way in which it is imbricated in digital media, an aspect of #FWP that offers both potential and limitations. Hutton theorises their own work in digital terms—they talk about their use of ‘technology as self-reflection’ and ‘radical sharing’ (a reference both to politics and social media). In the next section of this article, I look at these two digital strategies of #FWP, and ask to what extent they further the political goals of Hutton’s work.

Technology as Self-Reflection

The idea of creating an artwork that is a selfie-booth resonates with a growing body of literature on selfies and the potential they have to facilitate social transformation (Fink and Miller 2014; Murray 2015; Senft and Baym 2015; Sheehan 2015 & Shipley 2015) and citizenship. (Kuntsman 2017). Hutton became interested in the transformative potential of selfies while documenting their own transition (Shipley 2015: 409). They see selfie technology as providing a social/relational framework that structures peoples’ interactions with both themselves, and each other. They used selfies to navigate their change in gender identification from female to transgender, and to explore their own understanding and acceptance of this process. Hutton’s artistic journey coincides with their queer journey of self-discovery, and they regard the two as closely related: ‘I look at my living of fluidity in both artistic and gender sense’ (Hutton quoted in Shipley 2015: 409). Hutton’s early work is about making peace with themselves and their family [7], and later using the camera to find beauty in themselves. (Shipley 2015: 409) Shipley writes that Hutton’s self-portraits ‘blur photography and autobiography’ (Shipley 2015: 409). Hutton describes themselves as ‘self-mediating,’ as carefully and reflexively self-fashioning through the process of taking selfies as a proclamation of self-worth (Shipley 2015: 410). Nicholas Mirzoeff describes the capacity that we now have to create media and disseminate it ourselves as a form of self-representation as direct action (2015: 297).

In theory, the #FWP selfie-booth thus allows audience participants to participate in this direct action. The presence of Hutton’s shoes makes a symbolic visual link between the decolonisation process Hutton is attempting to undertake, and to which they are asking their audience to commit themselves. In photographing and tweeting the image of themselves endorsing Hutton’s #FWP message, they are joining their campaign to call for the deconstruction of white supremacy. Potentially, they are also ‘trying on’ a different subjectivity, and in so doing, engaging with a form of critical digital citizenship, a counter-hegemonic political engagement that reaches towards community building. Hutton here talks of the potential for healing #FWP offers its audience:

I’ve had people just come up to me and want to hug me and like take time, just hold a space, you know? And it’s easy to get lost in that and to feel good about myself in that way, but the real potential of the project is that white people can see a way out of white supremacy (Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

Of course, the piece itself is a gesture—it relies on the audience participants to do the work themselves to move it beyond a gesture and towards something truly transformative.

Hutton talks passionately about their own belief in this transformative potential:

I feel like everybody at the moment is only interacting with artwork through putting themselves in it. I feel like selfie art, or art that encourages the selfie, it’s a very provocative way of having people interact with your work … I do think, the power of social media, the power of these visual devices, or these multi-media machines that we carry with us, is about self-reflection. it exposes us to, first of all through social media, it exposes us to the language with which we can learn to self-reflect. I’ve learnt a lot about myself (Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

To some extent what we see in #FWP is their own very personal journey of self-reflection. While witnessing this might be thought-provoking or moving for some, there is of course no guarantee that setting up a selfie-booth to facilitate this decolonial journey for the gallery audience will have the desired effect, particularly given the deeply fragmented nature of South Africa’s publics, and the whiteness of South Africa’s art spaces (Lilla 2017).

Hutton describes ‘technology as self-reflection’ as a process of ‘analysing how meaning is made through the sharing of my image and the surveillance of my Fat Queer Trans White body’ (Hutton 2017: 5). Self-reflection here refers to the (systematic) observation and documentation of the (material and virtual) responses to Hutton’s performance. This suggests that the central purpose of Hutton’s project is about their own journey to expose and unpick their whiteness. In iteratively crafting a self-representation or counterimage that allows for political engagement and community building, Hutton attempts, at least temporarily, to resist the limits of their own whiteness.

The move from self to solidarity anticipated in the ‘radical sharing’ of this work, is more complicated. Hutton’s writes about coming ‘to performance from the documentation of performance,’ which suggests that the capturing or archiving of their work, is as important as the work itself. This is the opposite of the way that performance has traditionally been conceptualised and written about. Peggy Phelan writes, for example, that performance ‘becomes itself through disappearance’ (1993: 146). Munoz suggests this is particularly the case for queer performance:

Queerness is often transmitted covertly. This has everything to do with the fact that leaving too much of a trace has often meant that the queer subject has left herself open for attack. Instead of being clearly available as visible evidence, queerness has instead existed as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments, and performances that are meant to be interacted with by those within its epistemological sphere—while evaporating at the touch of those who would eliminate queer possibility (1996: 6).

Hutton’s work is definitively not about innuendo or disappearance. They operate by concretising and amplifying their physical performance through its digital documentation and circulation. Hutton is very consciously performing for the digital life of their piece. The performance is not ephemeral. Their enactment of Goldendean is directed both at material and virtual spaces. Social media, to Hutton, is not just a dissemination and archiving tool: it provides them with a virtual space within which people can communicate, and ‘another performance space in which live actions continue to reverberate’ (Hutton 2017: 21). The ‘radical sharing’ that I discuss in the next section relies on #FWP being crafted for both these spaces.

Radical Sharing

Hutton’s description of selfie-creation relates the process of both controlling and crafting a representation of oneself, and the deeper process of both self-reflection and empowerment that this facilitates. It is the making public of this self-crafting and (un)learning that constitutes Hutton’s artistic practice—what they call ‘radical sharing.’ Hutton attributes the concept of ‘radical sharing’ to fellow artist and friend Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, who explains it as privileging ‘the power of human interaction, of creating community, of deep listening, of sharing ownership, of really seeing one another’ (Nkosi 2015: 1). Like the idea of ‘technology as self-reflection,’ Hutton’s conception of ‘radical sharing’ suggests both a social and a digital process. ‘Radical sharing’ happens in person, through Hutton’s embodied performances and their associated conversations, online in conversations about the piece, in the sharing of photographs of the performance, and in the archiving of the project which Hutton has meticulously captured and uploaded to a public cloud folder. It is this process, built on Schechner’s (2013) idea of performances as ‘actions’ [8], that moves Hutton’s work from the individual to the collective. Hutton uses their performance process to break the fourth wall (the imaginary divide between performer and audience that keeps the audience as observers not participants) and foster ‘collective dialogue.’

Hutton is sharing not just their (un)learning process, but also themselves. They literally put their own body on the line in their performance work. Hutton conceptualises Goldendean as a kind of artistic lightning rod to absorb or defuse racial tension:

A lot of what I’m trying to do is find a way to become something else. There has to be a way that if we made ourselves, to unmake ourselves, you know. Like a kind of transmutation … I am effectively calling that violence onto me, so much of what I am doing is trying to make, like, the inherent violence of the white identity super visible, not only in what it perpetuates for black people, but what it does for people who identify as white (Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

Hutton describes how through performing #FuckWhitePeople, they are trying to surface and make visible the violence inherent in white supremacy, almost as a necessary penance for being white. The process of publicly sharing their body and making themselves vulnerable through their public performance can be seen as a ritual offering, and it is Hutton’s overtly queer/androgynous embodiment that underscores this process. In Hutton’s own words their performance:

[C]entres (their) Fat Queer Trans White body, and by making itself available for documentation by the audience to be generously shared across networks of friends and followers on social media; evolves into a collective work in which thousands of bodies and minds collaborate in an extended conversation around not only art, art practice, design and communication, but also language, politics, racism, white privilege, gender, trans identity and the embodiment of power in the decolonial moment (Hutton 2017: 25).

Of course, this statement by Hutton is performative, and arguably utopian. In reality, reactions to their work have been extremely varied, and many of the reactions (both positive and negative) have been as much to do with Hutton’s queer embodiment as the content of the piece. The following two sections look at some of these reactions and what they reveal about the political efficacy of Hutton’s work.

John Marnell, who works for GALA (the South African Gay and Lesbian Archive), describes how people have responded to seeing #FuckWhitePeople in workshops. For him, it is precisely Hutton’s queerness that ensures the work’s success:

I think people are seeing the embodiment of what they want to be happening, people get exhilarated by just the fuck you element … the race element, and the owning of the space … People respond most of all to the fact that this person is publicly playing with their gender and doing it with a sense of fun. I think it gives it a sense of relief, because things haven’t changed, you know…and people are still dealing with the same shit everyday … (people) actually just want to say: ‘Fuck White People.’ I’ve had enough. And so, seeing someone actually do that, who is white, in this kind of embodied way, people are just like, ‘finally!’ (Marnell, Interview in Johannesburg, November 2016).

Marnell describes Hutton’s work as productively breaking social taboos about what it is acceptable to verbalise, and therefore defusing some of the racial tension produced by the continuing structural legacy of apartheid. He also comments on the way in which he sees Hutton’s work as allowing a move beyond the self—as producing an effect of solidarity. he explains what he sees #FuckWhitePeople doing in terms of fostering cross-racial allyship:

It’s not about the individual, it’s beyond the individual. It’s like —what is this class of people that have access to certain resources, doing in this country? I think that’s really crucial, in that it does take it beyond an individual identity politics (Interview in Johannesburg, November 2016).

For Marnell, at least in his work with GALA, Hutton’s work is extremely productive, and works to enable necessary and important conversations about race.

Brett Rogers [9], a white South African blogger, sees Hutton’s #FuckWhitePeople as a gift. He writes about his own positive experience of engaging with Hutton’s work, and the sense of political agency it made him feel. Like Hutton, #FWP gives Rogers a sense that he is not trapped by his skin colour. Here, he explains this:

To FUCK the white in you is not a form of self-hatred, it’s a form of self-love, saying ‘Yes, I represent and continue to represent heinous crimes against humanity, now how can I move forward and change that representation. Fucking the white in you releases you from your representation and invites you get involved in the world (Rogers 2017).

Although Marnell and Rogers are clearly supporters of #FuckWhitePeople, and therefore sympathetic to Hutton’s intentions, many others are unsure as to how to respond to it. During their MA, Hutton presented their work at two sociology lectures at the University of Cape Town. Zethu Matebeni, one of the sociology lecturers who invited Hutton to talk to her second-year sociology class of 255 students, describes the students’ reaction to #FuckWhitePeople:

Even the black students were very uncomfortable, because for the first time, they don’t know how to engage, because now the thing we’ve been wanting is here … one student said, ‘actually, in a way, I’m relieved, because I can actually just sit and watch … and it’s great, because I’m so used to fighting, but now I don’t have to fight, I’m watching somebody doing the work’ (Matebeni, Interview in Cape Town, November 2016).

Despite the students’ discomfort, one of the students Matebeni describes recognises and appreciates Hutton’s gesture of allyship. #FuckWhitePeople, in surfacing and making white supremacy visible, has the potential to temporarily relieve the pressure of that burden on black students, who are constantly navigating its unspoken reality. Here Hutton, a white South African, is also accepting responsibility for contributing to anti-racism work.

This gesture was not well received by some. Members of Umhlangano, the decolonising collective at the University of Cape Town’s Hiddingh campus, of which Hutton was a part, saw their work as an act of white privilege, eclipsing their black protest (Hutton, Interview in Cape Town, November 2016; Sosibo 2017). As Sosibo writes, the #FWP emerged at a ‘moment in our history when the validity of white allyship itself (was) in question’ (2017).

Hutton also received numerous angry and violent reactions to their work from white, far right individuals and groups. They were subjected to online threats and abuse, often in the form of highly offensive personal attacks, including from a former Ku Klux Klan leader. In the following section I discuss the reaction to #FuckWhitePeople by the separatist political party The Cape Party. The Cape Party is a fringe right wing political party that advocates for an independent ‘Cape Republic.’ In August 2021, the Cape Party changed its name to the Cape Independence Party (Businesstech 2021).

The Cape Party’s Attack on #FWP

Although Hutton sees their work as an act of love, many do not. In January 2017, a group of Cape Party members restrained the security guards at the National Gallery in Cape Town and defaced Hutton’s selfie-booth by placing a large sticker reading ‘Love thy Neighbour’ across Hutton’s #FuckWhitePeople posters. Jack Miller, the leader of the party, accused Hutton of making ‘an overtly racist piece of work’ (van Niekerk & Blignaut 2017). The Party filmed their intervention and posted it on their YouTube channel. In the week following their gallery invasion, the Cape Party sought an order from the Cape Town magistrate’s court against the National Gallery to have Hutton’s work declared hate speech. Miller (the Cape Party leader) evoked the rainbow nation in justifying his court proceedings saying, ‘we find it sad that no one is talking about the rainbow nation anymore’ (van Niekerk & Blignaut 2017). The South African National Gallery defended #FuckWhitePeople and issued a statement defending their freedom to exhibit provocative and challenging work.

In July 2017, the South African Equality Court dismissed charges of hate speech laid by the Cape Party against the Iziko National Gallery’s display of #FuckWhitePeople. In the ruling, Chief Magistrate Thulare quotes Albert Luthuli (former leader of the African National Congress) and Nelson Mandela, both of whom wrote about their respective struggles against ‘white supremacy’ and ‘white domination’ (Thulare 2017: 5). Locating Hutton’s work within a legacy that includes Luthuli and Mandela, two of South Africa most revered leaders, was a glowing endorsement of #FuckWhitePeople, and a stern rebuttal of the Cape Party.

Hutton describes the judgement as ‘an extended piece of art criticism’ (2017:107), in which Thulare explains, for those that have not understood Hutton’s work, what it is #FuckWhitePeople is trying to achieve. He writes that Hutton is asking us to ‘reject, confront and dismantle structures, systems, knowledge, skills and attitudes of power that keep white people racist’ (Thulare 2017: 5). Section [29] of the ruling states:

[F]ear of losing the debate in the battle of ideas, is not enough reason to take the battle to the legal trenches and hope to have the canons of judgment from the courtrooms to shoot down and repress, curb or kill the opposing views. Issues that plague a nation need to be properly ventilated in all available fora of the nation if that nation is to properly account for a better future (Thulare 2017: 7).

The Artist Cannot Be Present

The court ruling, and Magistrate Thulare’s impassioned defence of freedom of speech, was undoubtedly a victory for Hutton and the South African National Gallery. However, the threats and insults Hutton received as a result of #FuckWhitePeople prompted them to perform their final MA show in a secret location, and broadcast it online as a projection onto the Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr statue in Church Square, Cape Town. It is interesting to consider whether the ultimate confining of this piece to a virtual performance should be seen as a celebration of the new spaces for expression offered by the digital realm, or as a confinement of Hutton’s visual disobedience to this virtual space. Perhaps Hutton’s movement between real and virtual space, and the tension that #FuckWhitePeople generates between Hutton’s control of the process of ‘technology as self-reflection’ (the use of technology to craft a representation of oneself, and the associated self-reflection and empowerment this process creates), and the surrendering of this control in ‘radical sharing,’ is ultimately what makes the piece work. In Hutton’s #FuckWhitePeople, their fat, trans identity is mobilised to complicate and interrogate whiteness, and the binaries through which race is often articulated. There is something hopeful in the idea that those marginalised by structural oppressions can work collectively to dismantle the architecture of these oppressions. In their work—to provoke self-empowerment, to start conversations, to encourage space for white South Africans to unlearn, to relearn—we see a tentative hope that substantive transformation in South Africa is underway despite, or perhaps because, of the end of the idealism that characterised the rhetoric of the ‘Rainbow Nation.’ However, the reception of the queer utopia offered though Hutton’s critique of whiteness, in the context of South Africa’s myriad social fragmentations, suggests a far more fragile, less confident, hope than that of the euphoria of 1994. It underscores also, the multiple difficulties of work that challenges existing social norms. hooks cautioned that ‘without justice there can be no love’ (2000: 30), and Hutton’s work suggests that without love there can be no justice.

Notes:

[1] A ‘fallist’ is the term used to describe an active member of the #FeesMustFall movement.

[2] In their MA thesis, Hutton (2017:8) references Walter Mignolo’s (2014:2) definition of a ‘decolonial gesture’ which he describes as a body movement or gesture which carries a decolonial sentiment or/and decolonial intention.

[3] Hutton identifies as neither a woman, nor a man, i.e. outside of the gender binary. Demelza Bush, another gender queer South African, has written eloquently about her own understanding of this here: http://bhekisisa.org/article/2015-04-10-00-i-am-genderqueer-comfortable-with-my-identity-at-last (last accessed 24 February 2022).

[4] http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/the-man-behind-that-wits-t-shirt-1983503 (last accessed 24 February 2022).

[5] https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/general-news/2016/feesmustfall2016/statements/offensive-graffiti-on-campus.html#sthash.oAcFvfKJ.dpuf (last accessed 24 February 2022).

[6] ‘In Cape Town, I walked into a room at a public university on the African continent, where I was to study for two years, and there were almost no black people in the room’ (Hutton 2017: 63).

[7] Written on her Face (2006) was a series of portraits of their mum, with an edited diary of her life (including accounts of the multiple beatings she received from their very violent father).

[8] See Hutton (2017: 19).

[9] Rogers, B. (2017), #FuckWhitePeople—or The Big Gift We’re Throwing Away.

REFERENCES

Allen, Theodore (1994), The Invention of the White Race, Vol. 1. London, New York: Verso.

Bennett, Jane (2018), ‘“Queer/white” in South Africa: a troubling oxymoron?’ in Zethu Matebeni, Surya Munro and Vasu Reddy (eds.) Queer in Africa: LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism, London, Routledge, pp. 99-113.

Bhorat, Haroon (2015), ‘FactCheck: is South Africa the most unequal society in the world?’ The Conversation, 30 September 2015, https://theconversation.com/factcheck-is-south-africa-the-most-unequal-society-in-the-world-48334#:~:text=The%20Gini%20coefficient%20is%20the,unequal%20countries%20in%20the%20world (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Booysen, Susan (ed) (2010), Fees Must Fall: Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa, Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Businesstech (2021), ‘Cape Party launches bid for Western Cape independence,’ Businesstech, 18 August 2021, https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/513798/cape-party-launches-bid-for-western-cape-independence (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Chigumadzi, Panashe (2015), ‘Why I call myself a “coconut” to claim my place in post-apartheid South Africa,’ Mail and Guardian, 24 August 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/24/south-africa-race-panashe-chigumadzi-ruth-first-lecture (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Chikane, Rekgotsofeste (2018), ‘Breaking a Rainbow, building a Nation: The politics behind #MustFall movements,’ Daily Maverick, 17 October 2018, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-10-17-breaking-a-rainbow-building-a-nation-the-politics-behind-mustfall-movements (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Dyer, Richard (1997), White: Essays on Race and Culture. New York: Routledge.

Evans, Martha (2010), ‘Mandela and the televised birth of the rainbow nation,’ National Identities, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 309-326.

Fink, Marty & Quinn Miller (2014), ‘Trans Media Moments: Tumblr, 2011-2013,’ Television & New Media, Vol. 15, No. 7, pp. 611-626.

Gamedze, Thuli (2017), ‘Michaelis in the age of FMF: Inside Operatives,’ Adjective, 1 March 2017, http://www.adjective.online/2017/03/01/michaelis-in-the-age-of-fmf-inside-operatives-thuli-gamedze (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Genette, Gerard (1997), Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gqola, Pumla Dineo (2015), ‘Race and/as the rainbow nation nightmare, WISER, Wits University, https://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/files/documents/Gqola%20-%202015%20-%20Public%20Positions%20-%20Race%20Rainbow%20Nation.pdf (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Gumede, Arabile & Amogelang Mbatha (2018), ‘Why Land Seizure Is Back in News in South Africa,’ Bloomberg, 1 March 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-01/why-land-seizure-is-back-in-news-in-south-africa-quicktake-q-a (last accessed 24 February 2022).

hooks, bell (2000), All about love: new visions, New York: Harper Perennial.

Hutton, Dean (2017), ‘Plan B, A Gathering of Strangers (or) This is Not Working,’ MA thesis, University of Cape Town.

Kuntsman, Adi (2017), Selfie Citizenship, Manchester: Palgrave Macmillan.

Leonardo, Zeus (2009) Race, Whiteness, and Education, New York: Routledge.

Lilla, Qanita (2017), ‘Setting Art Apart: Inside and Outside the South African National Gallery (1895-2016),’ PhD diss., Stellenbosch University.

Livermon, Xavier (2012), ‘Queer(y)ing Freedom: Black Queer Visibilities in Postapartheid South Africa,’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 18, No. 203, pp: 297-323.

Mignolo, Walter (2014), ‘Looking for the Meaning of “Decolonial Gesture”,’ Hemispheric Institute, Vol. 11, No. 1, https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-11-1-decolonial-gesture/11-1-essays/looking-for-the-meaning-of-decolonial-gesture.html (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Mirzoeff, Nicholas (2015), ‘Afterword: Visual Activism,’ How to See the World. London, Penguin, pp. 289-298.

Mouffe, Chantelle (2008), ‘Art and Democracy: Art as an Agnostic Intervention in Public Space,’ Open, No. 14, pp. 6-15.

Msimang, Sisonke (2016), ‘End of the rainbow,’ Overland, Vol. 223, pp. 3-11.

Munoz, Jose Esteban (1996), ‘Ephemera as evidence: introductory notes to queer acts,’ Women and Performance: Journal of Feminist Theory, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 5-16.

Munoz, Jose Esteban (1999), Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Munoz, Jose Esteban (2009), Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York: New York University Press.

Munro, Brenna (2012), South Africa and The Dream of Love to Come, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Murray, Derek Conrad (2015), ‘Notes to self: the visual culture of selfies in the age of social media,’ Consumption Markets & Culture, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 490-516.

Nicolson, Greg (2016), ‘University of Free State violence: “It was a matter of survival”,’ Daily Maverick, 24 February 2016, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2016-02-24-university-of-free-state-violence-it-was-a-matter-of-survival (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Nkosi, Thenjiwe Niki (2015), Knowledge Production Panel Presentation. Goethe Institute African Futures conference. [2015. 30 October]

Oswin, Natalie (2007), ‘The End of Queer (as we knew it): Globalization and the making of a gay-friendly South Africa,’ Gender, Place & Culture, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 93-110.

Phelan, Peggy (1993), Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, New York: Routledge.

Pithouse, Richard (2016), ‘The rainbow is dead – beware the fire, SA,’ Mail and Guardian, 3 March 2016, https://mg.co.za/article/2016-03-03-the-rainbow-is-dead-beware-the-fire-sa (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Reid, Graeme (2010), ‘The canary of the Constitution: same‐sex equality in the public sphere,’ Social Dynamics, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 38-51.

Rogers, Brett (2017), ‘#Fuckwhitepeople—Or the Big Gift We’re Throwing Away,’ Brett Rogers, 2 February 2017, http://www.brettrogers.co.za/blog/2017/2/7/whyfuckingwhitepeopleisfun (last accessed 2 February 2017).

Schechner, Richard (2013), Performance Studies. An Introduction, London: Routledge.

Senft, Theresa & Nancy Baym (2015), ‘What Does the Selfie Say? Investigating a Global Phenomenon,’ International Journal of Communication, Vol. 9, pp. 1588-1606.

Sheehan, Clare (2015), ‘The Selfie Protest: A Visual Analysis of Activism in the Digital Age. MSc thesis, London Scholl of Economic and Political Science.

Shipley, Jesse Weaver (2015), ‘Selfie Love: Public Lives in an Era of Celebrity Pleasure, Violence, and Social Media,’ American Anthropologist, Vol. 117, No. 2, pp. 403-413.

Smith, Sidonie and Julia Watson (2012), ‘Witness or False Witness: Metrics of Authenticity, Collective I-Formations, and the Ethic of Verification in First-Person Testimony,’ Biography Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 590-626.

Sosibo, Kwanele (2017), ‘Is “Fuck White People” fucking itself?,’ Mail and Guardian, 3 February 2017, https://mg.co.za/article/2017-02-03-00-is-fuck-white-people-fucking-itself (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Steyn, Melissa (2001), Whiteness Just Isn’t What It Used To Be: White Identity in a Changing South Africa, Albany: State University of New York Press.

Steyn, Melissa (2012) ‘The ignorance contract: recollections of apartheid childhoods and the construction of epistemologies of ignorance,’ Identities, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 8-25.

Stone, Margaret and Dale Washkansky (2014), ‘A Queer Thing: Reflections on the Art Exhibition Swallow My Pride,’ Radical History Review, Vol. 120, pp. 145-158.

Thulare, Daniel Mafeleu Case number: EC02/2017 Magistrates Court ruling on 4 July 2017.

Tucker, Andrew (2010) ‘The “Rights” (and “Wrongs”) of Articulating Race with Sexuality: The Conflicting Nature of Hegemonic Legitimisation in SouthAfrican Queer Politics,’ Social & Cultural Geography, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 433-449.

van Niekerk, Gerhard and Charl Blignaut (2017). ‘Art, death threats and hate,’ News24, 22 January 2017, https://www.news24.com/News24/art-death-threats-and-hate-20170121 (last accessed 24 February 2022).

Visser, Gustav (2013), ‘Challenging the gay ghetto in South Africa: Time to move on?’ Geoforum, Vol. 49, pp. 268-274.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey