Feminist Colour-IN: An Aesthetic Activism of Connection and Collectivity

by: Kim Donaldson & Katve-Kaisa Kontturi , May 15, 2019

by: Kim Donaldson & Katve-Kaisa Kontturi , May 15, 2019

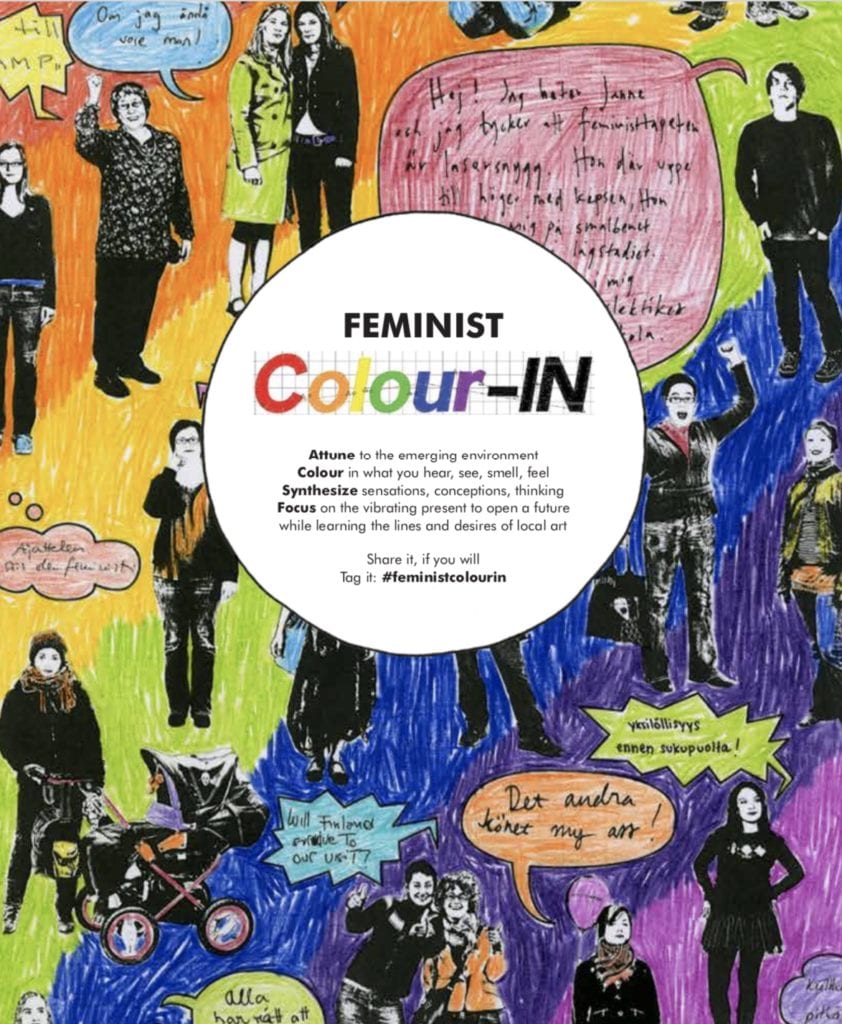

Attune to the emerging environment

Colour in what you hear, see, smell, feel

Synthesise sensations, conceptions, thinking

Focus on the vibrating present to open a future

while learning the lines and desires of local art

Share it, if you will

Tag it: #feministcolourin

The Feminist Colour-IN is a practice and a methodology where participant-performers colour-in black and white designs while attending a lecture in a teaching situation, a presentation at a conference, a group discussion in a domestic space, or, for example, a political speech or performance in a public space. (Fig. 1 & 2) Feminism is present in the practice either in the subject matter of the colouring designs, or in the content of the lecture/reading, or both.

Fig. 1 Feminist Colour-IN event during ‘Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism’, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, 3 March 2018. Photo by Lucia Rossi.

Fig. 2 Colouring ‘Feminist Lives’ at Norma Redpath House, Melbourne, 14 February 2018. Photo by Katve-Kaisa Kontturi.

The Feminist Colour-IN started in the aftermath of the ‘colouring book boom’ of 2015 [1], when we, artist Kim Donaldson and art scholar Katve-Kaisa Kontturi began to think about how colouring-in could be employed in activist and explicitly feminist ways. By then, a plethora of colouring books popularising ‘mindfulness techniques’ [2] had been brought onto the market. An example of these is Emma Farrarons’ The Mindfulness Colouring Book: Anti-Stress Art Therapy for Busy People (2015), which has grown into a series, including a colouring diary. These books suggest that colouring revitalises the overloaded brains of busy contemporary people, improves concentration, and generates more efficient work practices. This claim is based on the view that as a task, colouring is simple and repetitive enough to relax and invigorate the senses simultaneously. Similar claims of a ‘wellbeing effect’ have been made of knitting, where one stitch is repetitively made after another (Corkhill et al. 2015). Whereas ‘mindfulness’ colouring aims at creating wellbeing effects by emptying one’s mind, the Feminist Colour-IN offers a more activist and political take on it. Instead of prioritising the self-help benefits of colouring for individuals’ sense of focus and also productivity as members of society, we argue for colouring-in as a connective, collective activity.

The practice of Feminist Colour-IN closely links with and elaborates on recent discussions about practice-based, what could be called ‘more-than-linguistic’ knowledge production. Exceedingly, during the past twenty years, alongside the development of so-called artistic research or research-creation (Bolt & Barrett 2007 & 2013; Arlander 2016; Manning 2016), in fields from social sciences to education and humanities (and even natural sciences), different kinds of image and other more-than-linguistic methodologies have gained prominence. These varied methodologies include, for example, using images or puppets as active visual-material elements in an interview process that usually leans on verbal, mostly textual communication (Harper 2002; Petersen 2014); thinking in movement, ‘in the act’, ‘in the middle’ and not retrospectively (Manning & Massumi 2013); and different gentle modes of attention such as attuning, dancing, deep-listening or walking (Fast 2018; Oliveros 2005; Manning 2013; Springgay & Truman 2017). In these practices, the role of the enabling agencies of the more-than-linguistic is embraced, and the movements of the world are followed with great care to create new understandings not only of the world but with it (Kontturi 2018)–with sounds, images, gestures, colours. As Karen Barad (2007) puts it, in these practices, knowledge is made in intra-action, where what is created, is inseparably entangled not only with the ‘knower’ but also with the ‘known’ (see also Kontturi et al. 2018); it is collaboratively produced.

What is further common to these more-than-linguistic practices is the focus on the body and materialities and affectivities of praxis. Sensing and sensation are not kept separate but brought together. In this context, to colour-in is not just an activity of obediently applying chosen colour on a certain, pre-set design. Neither it is an exercise designed to improve the brain, coordination or concentration, and as such an exercise, which is sometimes thought to kill one’s own creativity because of all the predetermination loaded into it. Instead, to colour-in is to move your hand, your body, your pencil in relation not only to the lines and borders of that what is coloured-in but also in relation to that what is attended, sensed through listening, hearing, seeing, smelling. In this way, by way of colouring-in, new feminist knowledge is co-created by making sense of genders, sexualities and art through sensations. What we suggest is that this type of an embodied, affective more-than-linguistic practice not only produces knowledge but works as aesthetic activism (Kontturi & Tiainen forthcoming). In the following, we contextualise our activist practice further and introduce its different forms from booklets to collective colouring works and events.

Feminist Activisms from Major to Minor

Our colouring-in practice not only critically repurposes contemporary mindfulness techniques, and develops more-than linguistic knowledge practices, but it also, with appreciation borrows from different forms of feminist activist practices including the consciousness-raising of the late 1960s and 1970s. We suggest that similarly to consciousness-raising groups that empowered women and shared new knowledge through group discussions, colouring-in feminist designs can raise awareness of feminist topics and art. And, as we will explain later, colouring-in can also be used as part of collective discussions inspired by the very tradition of consciousness-raising groups. That is to say that whereas as a project and methodology the Feminist Colour-IN is a new practice and proposition, it has its precedents. These include Tee Corinne’s early Cunt Colouring Book (1989 [1975]) that spread cunt-positivity and raised knowledge of the varied vaginal looks and shapes through its real-life-like designs that thematically connected to the fleshy forms of feminist central core aesthetics of that time. Today, the number of colouring books with feminist imagery is growing, and books available include several timely issues for feminism such as body positivity and fat studies, embraced, for example, in Allison Tunis’s Body Love: A Fat Activism Colouring Book (2016). Our colouring booklets, for their part, aim to embrace generational, and also ethnic and cultural varieties of local feminist art.

Another form of feminist activism that we acknowledge, and that is also embedded in the title of our practice, is sit-in, where a public place is occupied by the bodily presence of demonstrators who want to raise attention to their cause quietly, ‘just’ sitting there and not moving until their opinion is heard and they reach their aim (Cullins 2018). What our practice picks up from the feminist tradition of sit-ins, is the quietness of the practice, the quiet bodily doing, and also the fact that Feminist Colour-IN is executed, mostly, ‘just’ by sitting and colouring-in.

Yet, as practice, the Feminist Colour-IN contests the normative understanding of activism as something associated with loud and ardent messages, outspoken charismatic leaders, and forms of protest such as mass demonstrations, processions, rallies and strikes that have clearly determined activist causes and outcomes usually, and that aim for wide media presence. One way to conceptualise the specific activist nature of Feminist Colour-IN is to understand it as ‘minor activism’. The recent burst of craft activism, craftivism, with its cross-stitched mini banners anonymously left in public space (Corbett 2013; Greer 2014) could be considered as a form of minor activism, but it is important to note that minor activisms are not only about size. The slow art movement, with its focus on time-consuming processual making, could be understood as minor activism also (Robach 2012; Wellesley-Smith 2015); however, minor activisms are not only about speed either. What minor activisms offer are more-than quantifiable measures: a subtle and attentive mode of practising activism that gently suggests other ways of living, being and making. Conceptually, minor activism links with the affirmative process philosophies of matter and relation. For Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, minor occurs in relation to major, yet its actions are not only reactionary towards the major, the minor is an unruly self-organising, creative force. As Erin Manning suggests, ‘minor isn’t known in advance. Each minor gesture is singularly connected to the event at hand, immanent to the in-act’ (2017: 2).

This is to say, that while the Feminist Colour-IN is committed to feminisms, how exactly it exercises its activism is open to each event, to each participant and the collectivities formed in the act(s) of colouring-in: in the intra-actions, in the co-emergences happening through the rhythmic, affective materiality of colours, lines, textures, volumes. For us, these sensational aspects integral to the Feminist Colour-IN make it an aesthetic activism of a minor kind.

The Booklets

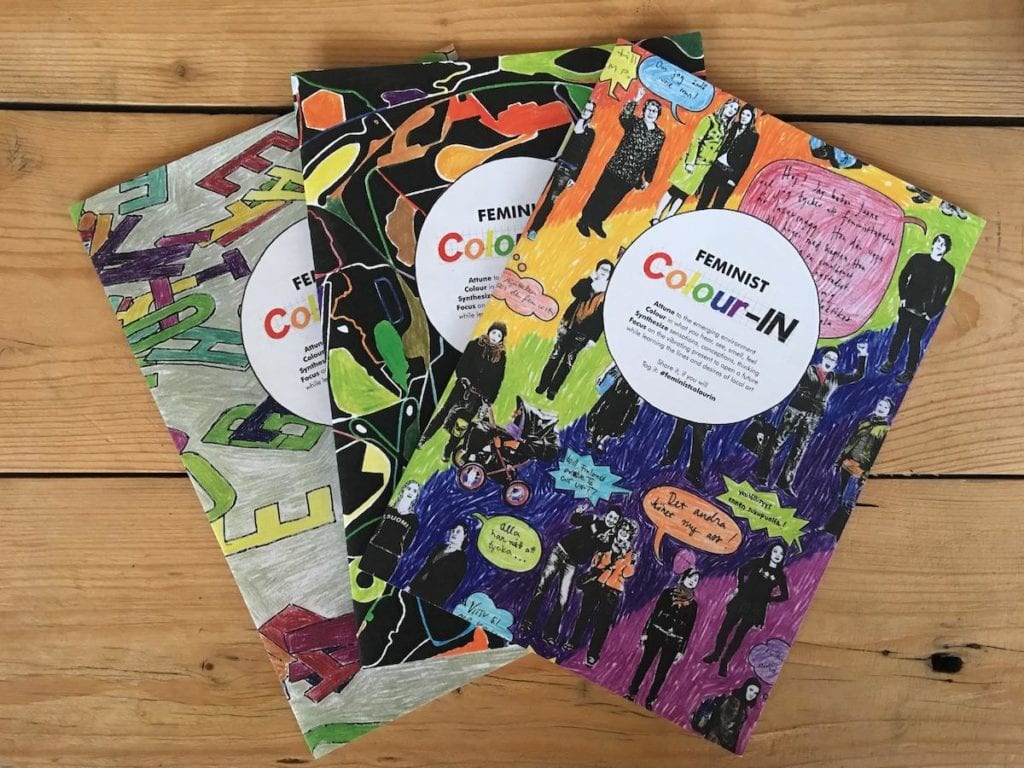

Fig. 3 Feminist Colour-IN booklets: Polish, Australian and Finnish editions. Photo by Kim Donaldson.

The first of our Feminist Colour-INs were built around the colouring booklets specifically created for events that took place at international conferences in Poland, Australia and Finland. (Fig. 3) These booklets are concise collections of 6 or 7 designs that were drawn ‘after’ the local feminist artists’ works of art; we also received some designs directly from artists. One of the booklets, the Feminist Colour-IN (2017) Finnish edition, is free for download online. (Fig. 4) In the Polish booklet we focused on offering a selection of artists of different generations, and in the Australian and Finnish booklets, we, in addition, aimed at offering a selection of designs by ethnically and culturally varied artists, including local Indigenous artists.

Fig. 4 Feminist Colour-IN (2017) Finnish edition.

At the New Materialisms conference in Warsaw, Poland (September 2016) and at the Somatechnics Conference in Byron Bay, Australia (December 2016) we shared the booklets with all interested conference participants, and had short introductory sessions at the opening events about how to use them: we explained how the participant-performers were invited to colour-in during the panel presentations and keynotes, and how they would simultaneously (an)archive, re-create the conference in colours and also learn about local feminist art–by following its lines as they filled the designs with colours. While the booklets were designed for individual use, we encouraged participants to discuss their colouring practice with others, show the colourings to us and have them documented, and to share them in social media with the hashtag #feministcolourin. In this way, the colouring-in practice was quietly present throughout these conferences: in almost every panel, we had someone colouring in, someone archiving, or re-creating, co-creating the conference in colours. It is to emphasise this active role that we speak of participant-performers, rather than just participants.

During and after both conferences, we collected and received some feedback in person and via email. Many praised how colouring-in helped them to focus better during the long conference days, and even reported how they have longed for colouring in at other conferences they attended afterwards. A couple of our participant-performers reported having felt that some other conference attendants seemed to think that colouring-in was not a respectful way to attend presentations and had received some angry looks when selecting pencils or sharpening them caused minor aural distraction. Some have found it easier to follow a presenter lecturing in a language not native to them when simultaneously colouring in: for them, the colouring opened more-than-linguistic connection with the speaker/content.

Fig. 5 Discussing lectures through individual coloured designs at the Jyväskylä workshop, 25 November 2017. Photo by Katve-Kaisa Kontturi.

In Jyväskylä, Finland, at the annual Gender Studies conference (November 2017) we organised a separate workshop, with its own introduction and closing/feedback sessions, which allowed us to have a more systematic collective reflection on the process and learn the participants-performers thoughts about the practice of colouring-in. During the feedback session, we discussed the conference and the practice of colouring-in through attending to the coloured designs. Many participants were able to remember the presentation’s content in detail when they referred to their colouring in: the colours they had used and lines that they had drawn. (Fig. 5) Drawing from the feedback we received, it seems that the Feminist Colour-IN can work like doodling (Andrade 2010): as an alternative and experimental practice for taking written notes. In this way, colouring functions as an embodied and material technique for participation and attention based on colour, line, and volume. It is important to note, though, that while colouring in can sharpen focus and concentration for some, other more language-oriented practitioners may require more time to perform this technique. Indeed, one participant-performer informed us that while they enjoyed the idea of colouring-in, they found that it overtook their attention, and hence they ended up colouring-in during the breaks rather than the speeches.

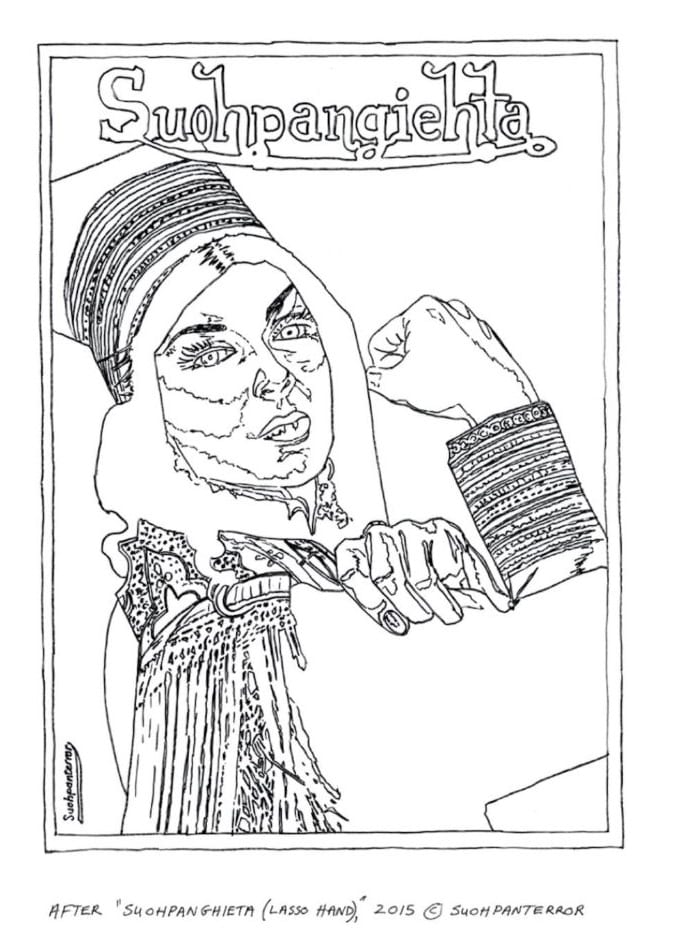

Fig. 6 Suohpanterror, Suohpanghieta in Feminist Colour-IN (2017) Finnish edition. Design copyright: Suohpanterror and Feminist Colour-IN.

We have also received some fascinating reactions in relation to the content of the designs, for example, in regard to our Finnish booklet that included a design after a piece by a Sámi group of anonymous artist-activists called Suohpanterror, where ‘suohpan’ stands for the traditional Sami lasso used to catch reindeer. The design was a Sámi appropriation of the famous ‘we can do it’ poster presenting a woman wearing a traditional Sámi outfit. (Fig. 6) This interestingly aroused sensations of uncomfortableness among some participant-performers: they were sensitive to which colours to use when colouring-in the outfit and the skin of the woman. What if their chosen colours would not be culturally appropriate? This, we think is an interesting ‘aesthetic activation’ that not only encourages reconsideration of one’s knowledge of and relation to local Indigenous cultures but also makes Indigenous people present where their culture might not be otherwise visible. Not too often is white feminism archived in and through Indigenous art.

Collective, Multi-piece Events

Whereas our booklets are designed to be coloured-in by individuals and the collective reflection happens only after individual colouring-in, our ‘multi-piece’ events offer a form of practice specifically designed to raise and embrace a stronger sense of collectivity. For these collective events, we have created large-scale designs that at the end of the event are compiled together from 49 separate A4 sized sheets of paper that the participant-performers have coloured during the event. Here we introduce two types of events that we have, by now, offered in multiple locations and contexts, from classroom situations to conferences, residencies, major art exhibitions and outdoor events.

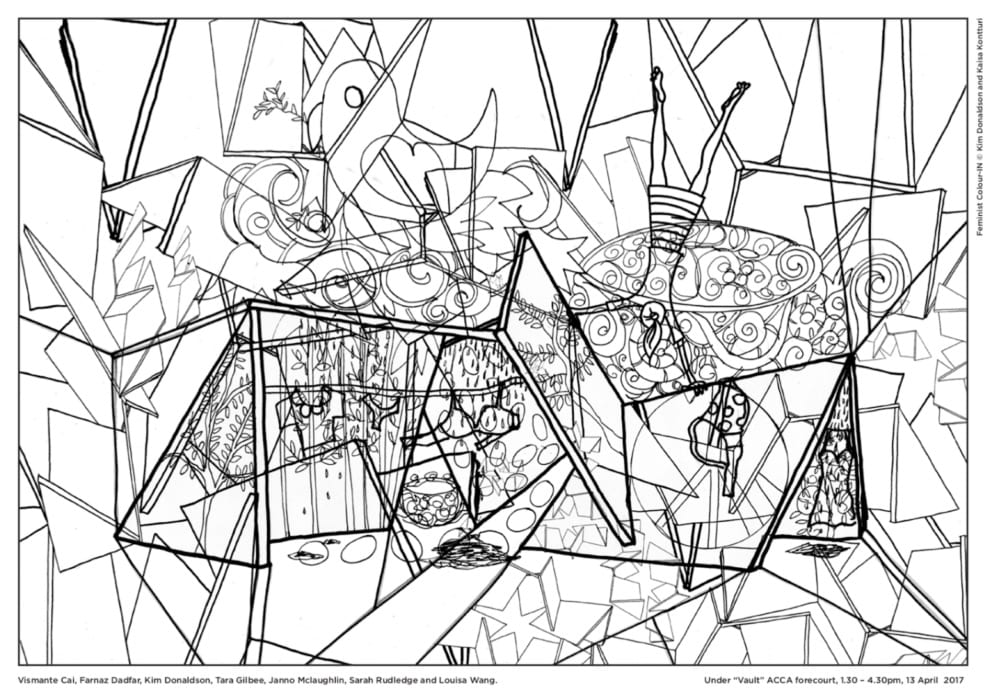

Fig. 7 Feminist Colour-IN ‘Under Vault’ event, Melbourne, 13 April 2017. Alyson Campbell reading Sara Ahmed. Photo by Lucia Rossi.

Fig. 8 Collaboratively designed colouring illustrations for, the ‘Under Vault’ Design copyright: Vismante Cai, Farnaz Dadfar, Kim Donaldson, Tara Gilbee, Janno McLaughlin, Sarah Rudledge, Octora Permana and Louisa Wang.

Our first collective event took place in Melbourne in April 2017, on the open public space located between ACCA (Australian Centre for Contemporary Art) and the Victorian College of the Arts at The University of Melbourne, where Kim Donaldson worked with her students to create a collective design. (Fig. 7) The design was an elaboration on a male Australian artist’s Modernist sculpture, known as ‘Vault’ that governed the public space of the event. The students’ (feminist) elaborations were combined into large designs that were then divided into 49 sheets of paper to be coloured-in during the event. (Fig. 8) For the event, we invited nine local feminists, including artists, students, professors and activists of various cultural backgrounds to read their favourite feminist texts in different languages. When compiled together after the event, the colouring-in formed a portrait of multiple feminisms that relied on collective activity that combined the skills, knowledge and aesthetic capabilities of the participating people–different viewpoints, educational backgrounds, ages and cultures.

In February 2018, we participated in a feminist residency series called ‘Doing Feminism: Sharing the World’ curated by Anne Marsh and Caroline Phillips, working again around a site-specific design by Kim Donaldson that was determined by the location of the residency, the house and studio of Australian artist Norma Redpath. This time the set-up was more intimate and specific: we invited women of different generations and ethnic backgrounds involved in the contemporary art world to tell stories of their feminist lives. (Fig. 2) The inspiration for the theme about feminist lives came from a performance by Melbourne artist Katie Sfetkidis ‘Making a Feminist Life’ (following Sarah Ahmed), who also performed at the event. Colouring around a dinner table, while listening to each other, we, again, documented our multiple feminisms into a colourful, collective work of art, but also, and importantly, offered a way to connect with other women beyond cultural and generational divides. What we suggest is that the intensive, aesthetic qualities of colouring-in, its material practice of lines, body movements and sensorily affective colours can facilitate a sense of connection among the participants. Indeed, many of the participant-performers referred to intimate feelings of compassion and understanding across generations and social hierarchies, which emerged when they shared life stories during the colour-in, while attuning to each other’s movements and actions (see Kontturi & Tiainen, forthcoming; Fitzpatrick & Kontturi 2015). Together, we shed tears of sympathy, fury, and joy, and learned a lot while co-creating our portrait in colours.

The Coats & Futures of Feminist Colour-IN

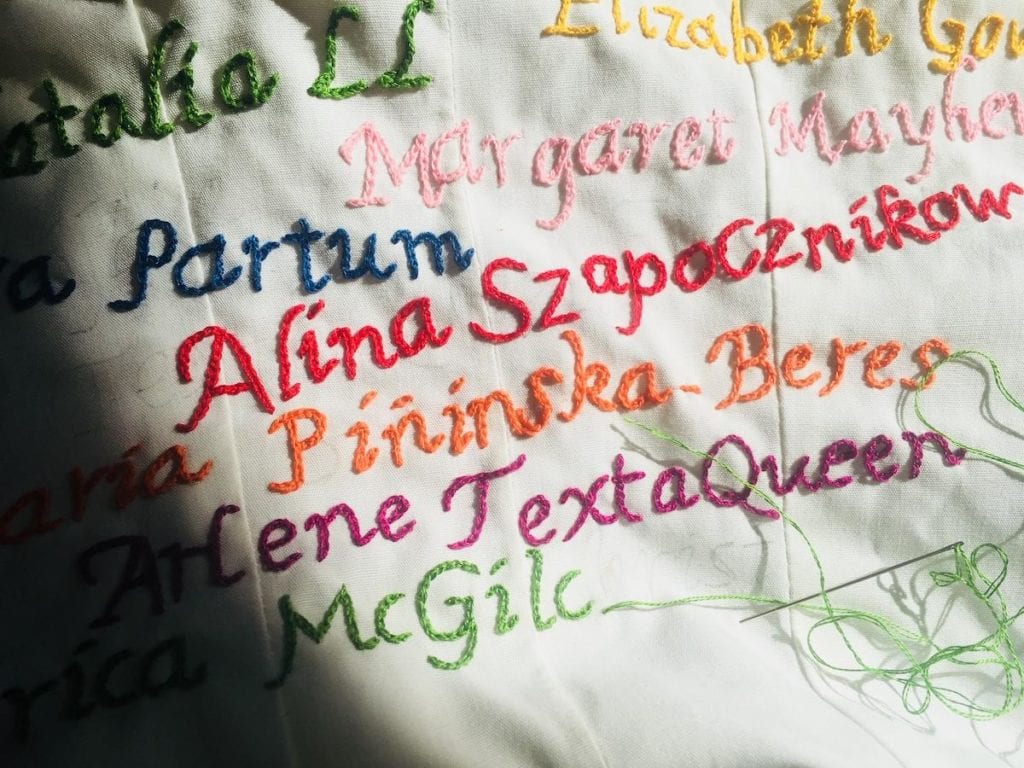

When practising colouring-in, we wear our lab coats to identify us, and also to establish our practice. But the coats are more than identifiers: they are works of art in progress, slowly being covered by the names of the artists involved in our project and the locations of the feminist events held. (Fig. 9) By embroidering the names of artists and events, we take the time and appreciate the work of those involved. This is yet another way of creating a feminist collective that is growing, open for new ones to join in.

Fig. 9 Embroidery being sewn on a Feminist Colour-IN jacket, 4 February 2018. Photo credit: Katve-Kaisa Kontturi.

By now, we have accumulated a sizable collection of coloured designs, both in paper and digital form. While colouring booklets are something that people can choose to keep, or even give to others to colour-in, some people have wanted to give them back to us for our archives. With the help of this material, the hashtag #feministcolourin and our digital documentation, the project now has an expanding multiform archive. Importantly, this archive not only reflects and records embodied processes of colouring-in but also adapts to new conditions as they arise. Attesting to this, we never aim at perfect, obedient documentation. Often our multi-piece events end up with one or more pieces missing or upside down–that is the nature of collective work; not only are connections formed but gaps too. Neither do we hope for a certain style of colouring-in; on the contrary, we encourage all styles, and are more than happy to include unfinished and unworked colouring-ins.

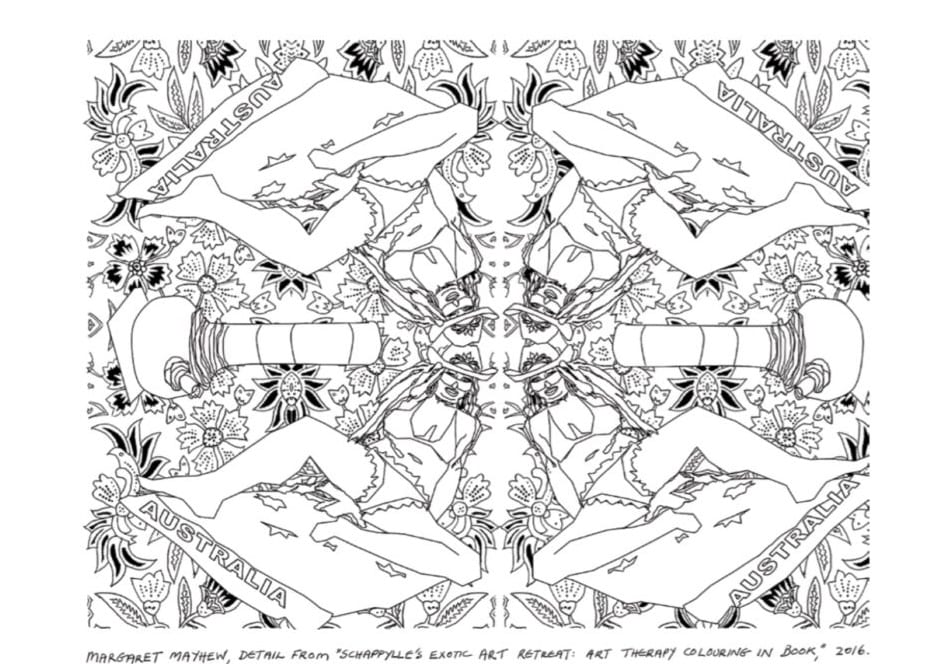

Fig. 10 Margaret Mayhew, Schapylle’s Exotic Art Retreat: Art Therapy Colouring in Book (2016), previously published in the Feminist Colour-IN booklet (Australian edition), © Margaret Mayhew, Kim Donaldson and Katve-Kaisa Kontturi.

The feedback that we have received helps to direct our practice towards the future. For example, some participant-performers have commented on how colouring designs that involved text can disrupt the flow of following the design, or interfere with concentration. Following this, we have plans to focus on more image-based designs, and also explore mandala-type designs (see also Curry & Kasser 2005), a version of which you can find in Margaret Mayhew’s design available in our Australian booklet. (Fig. 10) Another new direction is that we have started to involve the public in the creation of the designs more. As part of the exhibition ‘Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism’ at one of Melbourne’s preeminent art institutions, the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (December 2017-March 2018), we organised a design workshop, the results of which were then incorporated into a combined design and later coloured-in during our event.

Last, but not least, we want to emphasise that Feminist Colour-IN not only creates colouring booklets and multi-piece designs but also organises events. By way of example, we also hope to encourage others to create feminist colour-in designs and to apply them to activism, pedagogy and other possible purposes. We strongly believe that through its sensory and affective qualities, the embodied, more-than-linguistic practice of colouring-in can create a unique collective and connective space for shared experiences, new communities, and futures even.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our research assistant Otto Lehtonen who helped us with the first version of this essay. We would also like to acknowledge the indispensable work of our graphic designer and artist Sarah Rudledge–our designs would not exist without her. Finally, We want to thank everyone involved in the processes of the Feminist Colouring-IN including the participant-performers at the Australian Lesbian Medical Association conference in Adelaide and students at the Universities of Melbourne, Turku and Åbo Akademi.

Notes

[1] See https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/05/colouring-books-for-adults-top-amazon-bestseller-list.

[2] Mindfulness refers to a calming, anxiety-releasing body-mind technique that promotes wellbeing and focus (Kabat-Zinn et al. 1992). It is also a registered product and a mental-health program devised by Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founding Executive Director of the Center (sic) for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Many companies, including universities across the Western world, offer Mindfulness services to their employees. As the back cover of the Feminist Colour-IN booklet claims, ‘today mindfulness has become a ‘neoliberalist’ technique for promoting peace of mind to produce focused workers capable of multi-tasking for a greater profit, separated from its spiritual origins’ (2017).

REFERENCES

Andrade, Jackie (2010), ‘What Does Doodling Do?’, Applied Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 100-106.

Arlander, Annette (2016), ‘Artistic Research and/as Interdisciplinarity’, in Catarina Almeìda & Andre Alvez (eds), Artistic Research Does Series, Oporto: i2ADS Research Group in Artistic Education/Research Institute in Art, Design and Society, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, pp. 1-27.

Barad, Karen (2007), Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham: Duke University Press.

Barrett, Estelle & Barbara Bolt (eds) (2007), Practice and Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Inquiry, London & New York: I B Tauris.

Barrett, Estelle & Barbara Bolt (eds) (2013), Carnal Knowledge: Towards A ‘New Materialism’ Through The Arts, London & New York: I B Tauris.

Corbett, Sarah (2013), A Little Book of Craftivism, London: Cicada Books.

Cullins, Isoke (2018), ‘A Brief History of Feminist Protests’, Makers, 19 March 2018, https://www.makers.com/blog/brief-history-feminist-protests?guccounter=1&guce_referrer_us=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_cs=wYsPQkJiVaZ2d34TVLwY5g (last accessed 1 March 2019).

Curry Nancy A. & Tim Kasser (2005), ‘Can Coloring Mandalas Reduce Anxiety?’, Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 81-85.

Farrarons, Emma (2015), The Mindfulness Colouring Book: Anti-Stress Art Therapy for Busy People, London: Boxtree.

Fast, Heidi (2019), ‘Vocal Nest: Non-Verbal Atmospheres That Matter’, JAR: Journal of Artistic Research, No. 16, https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/387047/387048/0/0 (last accessed 22 February 2019).

Feminist Colour-IN booklet (Finnish edition) (2017), available at the Feminism Colour-IN facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/652782934885841/ (last accessed 22 May 2018).

Greer, Betsy (2014), Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, Toronto: Pulp Press.

Harper, Douglas (2002), ‘Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation’, Visual Studies Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 13-26.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1992), ‘Effectiveness of a Meditation-Based Stress Reduction Program in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders’, American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 149, No. 7, pp. 936-43.

Kontturi, Katve-Kaisa (2018), Ways of Following: Art, Materiality, Collaboration, London: Open Humanities Press,

Kontturi, Katve-Kaisa & Milla Tiainen (forthcoming), ‘New Materialisms in the Studies of Art: A Conceptual Mapping of Co-Emergence’, in Felicity Colman & Iris van der Tuin (eds), Methods and Genealogies of New Materialisms, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Kontturi, Katve-Kaisa, Milla Tiainen, Tero Nauha & Marie-Luise Angerer (eds) (2018), Aesthetic Intra-Actions: Practicing New Materialisms in the Arts Special Issue, inRuukku: Studies in Artistic Research, No.9, https://ruukku-journal.fi/en/issues/9 (last accessed 8 February 2019).

Oliveros, Pauline (2005), Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, Lincoln NE: iUniverse.

Petersen, Kit Stender (2014), ‘Interviews as Intraviews: A Hand Puppet Approach to Studying Processes of Inclusion and Exclusion among Children in Kindergarten’, in Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 32-45, https://journals.hioa.no/index.php/rerm/article/download/995/873/ (last accessed 22 February 2019).

Robach, Cilla (ed.) (2012), Slow Art, Stockholm: Nationalmuseet.

Springgay, Stephanie & Sarah Truman (2017), Walking Methodologies in the More-than-human World: WalkingLab, London & New York: Routledge.

Tee, Corinne (1989 [1975]), Cunt Colouring Book, San Francisco: Last Gasp.

Tunis, Allison (2016), Body Love: A Fat Activism Colouring Book, https://www.amazon.com/Body-Love-Activism-Colouring-Book/dp/1523352779 (The book is available for free via Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited) (last accessed 30 May 2018).

Wellesley-Smith, Claire (2015), Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art, London: Batsford.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey