Hard Lines, Soft Focus?: A Discussion of the Craft in the Art of Charlotte Hodes

by: Hannah Westley & Charlotte Hodes , December 13, 2021

by: Hannah Westley & Charlotte Hodes , December 13, 2021

Introduction

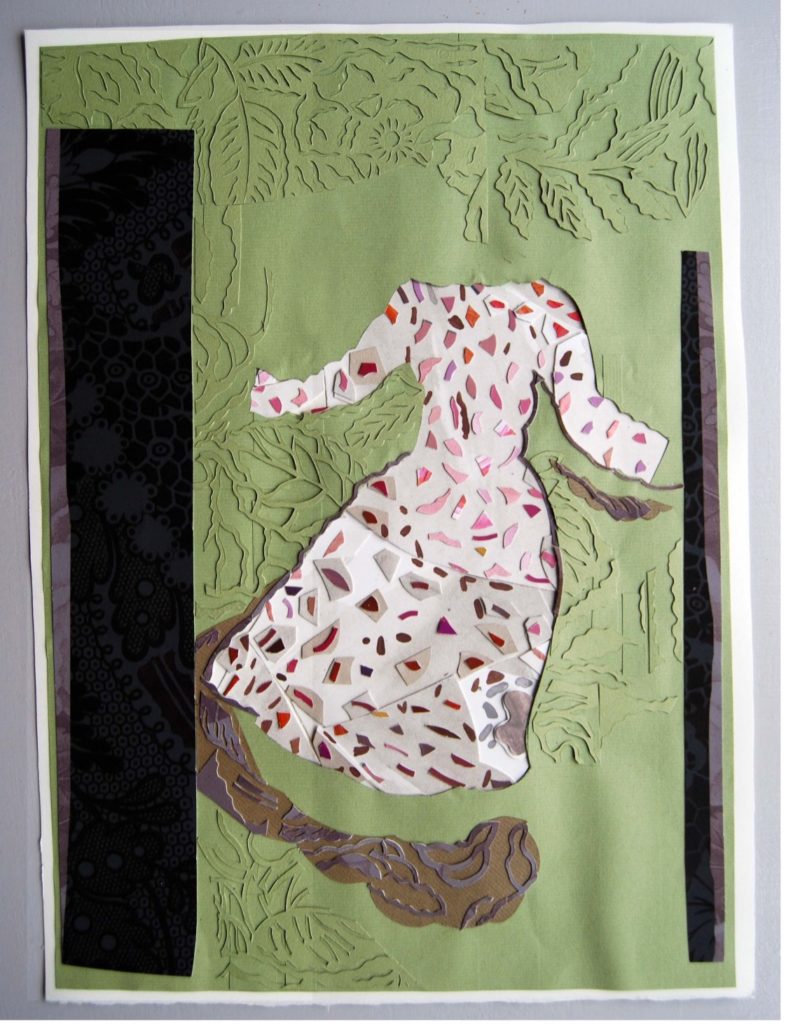

I live with a papercut [1] by the artist Charlotte Hodes (See Figure 1 below). It measures 40 by 30 cm and sits in a simple light wood frame. The image is composed of a white patterned dress against a green background. The dress floats free of a body, bordered by two vertical dark lines. It seems to be floating upwards to the green space above, trailing a brown shadow in its wake. Has this piece of feminine apparel floated free of its moorings, its tethering; has it become unhinged? Is it lost or liberated? Where is the body it may have contained? Did the body free itself of the dress or did the dress free itself of the body? It recalls poet and essayist Lisa Robertson’s thoughts on the metaphysical appeal of fashion, ‘[t]ime in the garment is what I repeatedly sought, because sartorial time isn’t singular but carries the living desires of bodies otherwise disappeared’. (2020: 18) Some days the light falls onto the image in such a way that all the details of the textured papercut reveal themselves to me: the green foliage against the green background; the intricate lace-like patterns in the dark velvety borders; the pinks, purples and browns of the jewelled shapes overlaid on the white dress. Other days, the image is two-dimensional, an elegant arrangement of shapes on a flat surface. I would like to run my fingers over the fine filigree of the cut-out shapes. I am reminded of standing in galleries, wanting to stroke the heavy impasto oil paint of colourful abstract canvases, to caress the flowing shapes of a bronze sculpture—the imperative desire to touch combined with the impossibility of touch: texture invites tactility. Charlotte Hodes’ artwork could well be a metaphor for our pandemic times. I live with the papercut, but it does not reveal itself to me—sometimes, fleetingly, I see the process of its production.

Scholarship and art criticism have increasingly struggled to find a definition for craft as a creative discipline (to differentiate it from art) since the 1970s, when craft objects started to make irreversible inroads into spaces previously reserved for fine art. [2] Craft has alternately been defined as a popular art form, as something that is functional or has a use (M. Anna Fariello in Buszek 2011: 36), or something that is authentic in its use of materials. (Langlands 2019: 22) Another recurring definition has resorted to the making of the craft object: the trace of the maker in the finished product, its essentially handmade nature. [3] While this definition is problematic, obviating, as it does, the handmade nature or the making of craft’s seeming other (art) in the historic dominant discourse, it is the making or craft, in other words the process, that is the common thread binding these definitions. Some claim that it is in the difference between the two disciplines—art and craft—that the value of craft lies; others say that the discipline of craft is at the heart of a contemporary art agenda. (Bryan-Wilson 2013: 7-10) Others, such as Louise Mazanti, argue that we should break with these definitions and move concepts of craft away from the ‘making’ to the ‘being’, from the ‘process’ to the ‘doing’, to examine the role of craft in contemporary society. (Buszek 2011: 60) Following Mazanti, I believe that these definitions are not enough to contain the dynamic slippage of ‘craft’ the verb and ‘craft’ the noun. In this essay, I propose that a more useful consideration of the crafting process, or the application of craft to ‘art’, lies in the approach of new materialism: in the intra-actions [4] that occur between artist, materials, tools, technique, spectator, and dominant discourse. These intra-actions give rise to a vibrant relationship where meaning is not fixed, identity becomes unstable, and it is only in the configuration of this ‘becoming’ that an understanding of Charlotte Hodes’ work is possible.

This essay looks at the crafting process in the production of work that is classified as ‘art’—defined as such through its inclusion in spaces set aside for the exhibition of art: museums and galleries. The crafting process behind this artwork is essential to its meaning or, in Mazanti’s words: its ‘doing.’ Charlotte Hodes’ artwork takes crafting techniques and objects associated with traditional—particularly feminine—crafts, and displaces the values commonly linked with art/craft. She undoes the aura of ‘authenticity’ traditionally associated with the handmade nature of craft objects, and refocuses attention on how her art comes about through a process of intricate labour. When her work incorporates craft objects, in the form of ceramics, these ceramics have come about as the result of an industrial production process, with transfers imposed in a factory. Thus, a consideration of her work undermines frequently made assumptions about the intensive labour invested in the craft object, compounding values associated with craft and conceptual art (assumed to involve intellectual rather than manual skill). It is partly in this reversal of values that preconceptions and assumptions are challenged, and where technique becomes an active agent for shifting our understanding of the art/craft discourses to open up new spaces for meaning.

Charlotte Hodes is a multimedia artist who trained as a painter at the Slade School of Art, UCL in the early eighties. She has exhibited widely since then, and her work is held in public collections at institutions that traverse the art/craft divide: from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, the Berengo Centre for Contemporary Art and Glass Murano, to the Spode Museum. Hodes draws on craft processes to create imagery that is situated within the language of fine art. She brings her experience as a painter to both her intricate papercuts and large-scale installations, in which ceramic ware serves as her alternative canvas. It is within this cross-over or dissolution of boundaries that Hodes’ work resonates.

Work in Progress

This is an essay about the artistic process, and as such it made sense to Charlotte, and to myself, to focus on a work in progress to allow for an immediate interrogation of tools and technique. The essay is based on a correspondence that progressed through a series of questions (mine) and answers (hers) over email in 2020/21. I began by asking Charlotte to describe the piece she is currently working on:

I have been working on a new series of papercuts that are around women (no surprise) that will be part of a body of work to include a ceramic installation. It is centred on professions/activities (across science and humanities such as astronomy, aviation, oceanography, writing, activism) and on women who have been pioneering in each area. This will be a homage to women’s impact on others, their contribution to the professions and to advancing society for the benefit of all. It has taken me a while to shape the project though I have already made a few papercuts over this past year. They are not portraits as such (another conversation), and while the figure silhouettes are pivotal, the images also depict tools and attributes associated with the professions and the women themselves.

There is another underlying theme around communication, with women endeavouring to connect and communicate with each other through various means. This idea began with my papercut series, ‘Perpetual Night’ 2019, in which a woman, confined within an interior space, makes her way through, over and across furniture, but it has been brought into sharper focus since the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is only through making the drawings and papercuts that I begin to get a grip on the ideas that are indistinct in my mind. It is always a rather painful and slow process to begin when you don’t know quite what you are doing.

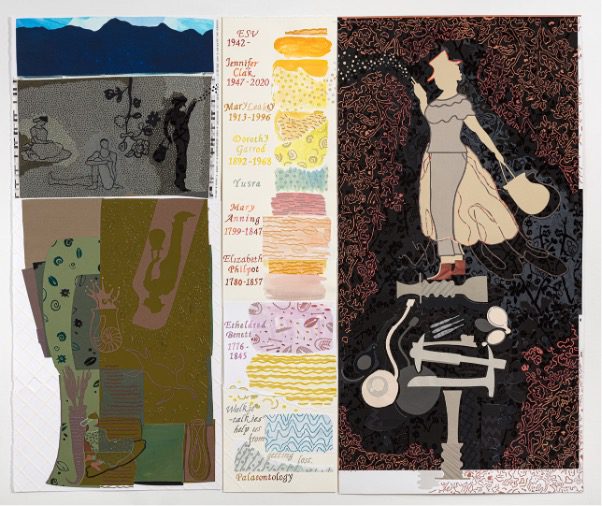

This work is still in the studio and unseen, so I am not sure if this is good or not. It is certainly current. I enclose a few studio pics. It is in 3 sections, total dimension 126 x 150cm. Lots of detail.

(Figure 2, reproduced below, is the work Charlotte is referring to.)

As Charlotte remarks, the theme of the new work is no surprise. Her work has almost always incorporated representations of the female form, from her first solo exhibition of paintings in 1991 to Surfing History in 1999—which drew upon female representations in art history—to 2019’s After the Taking of Tea. The female figure, often a self-portrait, is an omnipresent feature of her work, as I have noted elsewhere. (Westley 2016) Here, we see Charlotte giving those female figures a clear social and professional identity. I enjoy the way in which the tools of this male-dominated profession, with their hard lines and pointed edges, contrast with the round and softened contours of the female figure. The intricacy and detail of the overlaid papercuts recall here the lined patterns and indentations in the fossils these women might have found. Again, I am unsurprised to learn that the project will include a ceramic element. Charlotte’s shift into forms other than painting began over thirty years ago, first with collage, and then ceramics after a 1996 invitation to visit the factories in Stoke-on-Trent, a British city known since the seventeenth century for its manufacture of pottery.

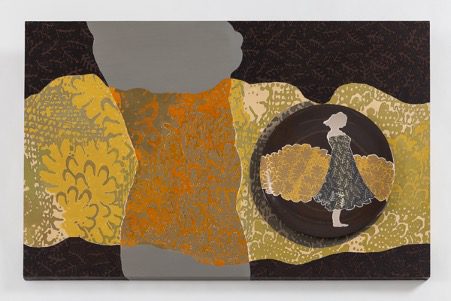

Within the context of the craft debate, Charlotte’s use of ceramics provides an interesting starting point. For an artist for whom process is paramount, and whose engagement with materials runs parallel to thought (working with the materials engenders new ideas, while new ideas might dictate different materials), she demonstrates a certain indifference as to how those ceramics are made. Indeed, she calls her ceramics ‘ready-mades’. (For an example, see Figure 3) In the use of this term, the incorporation of plates in her paintings recalls the Surrealists’ use of the readymade, through which they questioned the process by which an object becomes art and which, over the course of the twentieth century, became a staple feature of much contemporary art. About his now-celebrated readymade, the porcelain urinal entitled Fountain, Duchamp wrote: ‘[w]hether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—and created a new thought for that object’. (1917: 5) Duchamp’s statement is typically disingenuous: the urinal’s ‘useful significance’ did not disappear, but was transformed—it remained, in the scandalised gaze of its contemporary public, a signifier of use. If use has traditionally been a defining characteristic of craft—in the words of William Morris, ‘[h]ave nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’ (2018: 57)—have Charlotte’s ceramic objects been rendered useless, or has their use simply been transformed? In a later exchange in which Charlotte answers my questions about her ceramics, she writes:

I work with ceramicists who make the forms—mould-made, hand built and thrown—and who do all the technical work on glazing and firing etc. I myself work on the ceramics using techniques that include hand painting; application of ornamental elements (sprigs); applying coloured slips through hand cut stencils (so working with unfired clay though I haven’t done this for a while, see work from my Wallace Collection exhibition and Marlborough Gallery exhibition) and silkscreen and digitally printed enamel transfers that I hand cut and apply to the glazed ware.

This commentary reveals that Charlotte’s use of ceramics in her paintings designates them as readymades, but they are not, in fact, similar to Surrealist readymades, whose artistic function or signification was the disruption of the artistic process. Hodes’ multimedia pieces signify as a whole: the ceramics are simply already made [5], and as such enter into a repertoire of readymade elements at the artist’s disposal, including, as we will see, fabric motifs and other archival images.

I ask Charlotte how she appropriates, transforms and uses her readymades:

If I am working on ready-made tableware, for example After the taking of Tea , I develop my drawings and visual research using the computer to create the collage material that I then output for ceramic application. I use photoshop to create transfer ‘positives’ that I then have silkscreen printed. I print texts and some transfers digitally through a bureau. In this way, I accumulate multiple colour and pattern printed ‘sheets’ that I then cut up with the scalpel, applying and layering them onto the ware. A colleague fires them in her kiln. Not having my own kiln impinges on the potential to experiment but I guess this limitation is useful as I don’t get involved with the chemistry of ceramics which I have no interest in or creatively, have no need to be engaged with.

Sara Ahmed provides a helpful perspective in her interrogation of ‘use’ in What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use (2019). Ahmed cites Howard Risatti’s notes in A Theory of Craft:

[u]se need not correspond to intended function. Most if not all objects can have a use, or, more accurately can be made usable by being put to use. A sledgehammer can pound or it can be used as a paperweight or lever. A handsaw can cut a board and be used as straight-edge or to make music. A chair can be sat in and used to prop open a door. These uses make them ‘useful objects’ but since they are unrelated to the intended purpose and function for which these objects were made, knowing these uses doesn’t necessarily reveal much about these objects. (2007: 26)

Ahmed develops Risatti’s logic further, and asks when the story of use would begin; perhaps, she suggests, the starting point for use is always arbitrary, ‘use takes us back to how such-and-such thing came to be recognisable as such-and-such thing’. (2019: 24) Charlotte’s ceramics may not have a conventional use, but she uses them as plates in her paintings for their very quality as plates. In other words, the ceramics function as signifiers of use.

If Charlotte’s work with ceramics, through its incorporation of the craft object, aligns more with Peter Bürger’s definition of the avant-garde (1984)—traversing the art/life dichotomy by blurring that distinction through the appropriation of familiar or functional objects into an art sphere—than with the concept of art for art’s sake [6], what strikes me as significant here is her subversion of the crafting imperative. If the Arts and Crafts movement’s intention was to maintain the indexical mark of the maker in the unique handmade nature of the object, Charlotte reverses this strategy. She effaces herself from the crafting/making of the craft object, the plate, which is manufactured in a factory, like the objects of the industrial revolution that Morris’ movement needed to distinguish itself from, or the ephemeral objects of turbo-consumerism that the current Craftivists reject. Instead, she handworks and crafts the surrounds that hold and frame the craft object. In this way, the original use/function of the plate is transformed, and the values commonly used to define studio craft reallocated. To further muddy the waters, I recall that at its root, the word ‘manufacture’, which we associate with industrial mass production, actually means ‘to make by hand.’

My exchange with Charlotte continues thematically. Our conversation is shaped by the technological medium of its communication: questions asked and answers received that once sent cannot be retracted, like the definitive cut of a scalpel’s blade. Nevertheless, this commentary, in its transposition from email to document, can be rejected, reconsidered and replaced. As I ponder the starting point for our essay, I ask Charlotte about the starting point for her working process. I search for articles in digital archives, looking for scholarly debate and definitions. What is the role of research (for example, of motifs) in her work? What variety of sources does she use? And how is this source material re-(con)figured through both analogue and digital means?

On Pencil Drawings

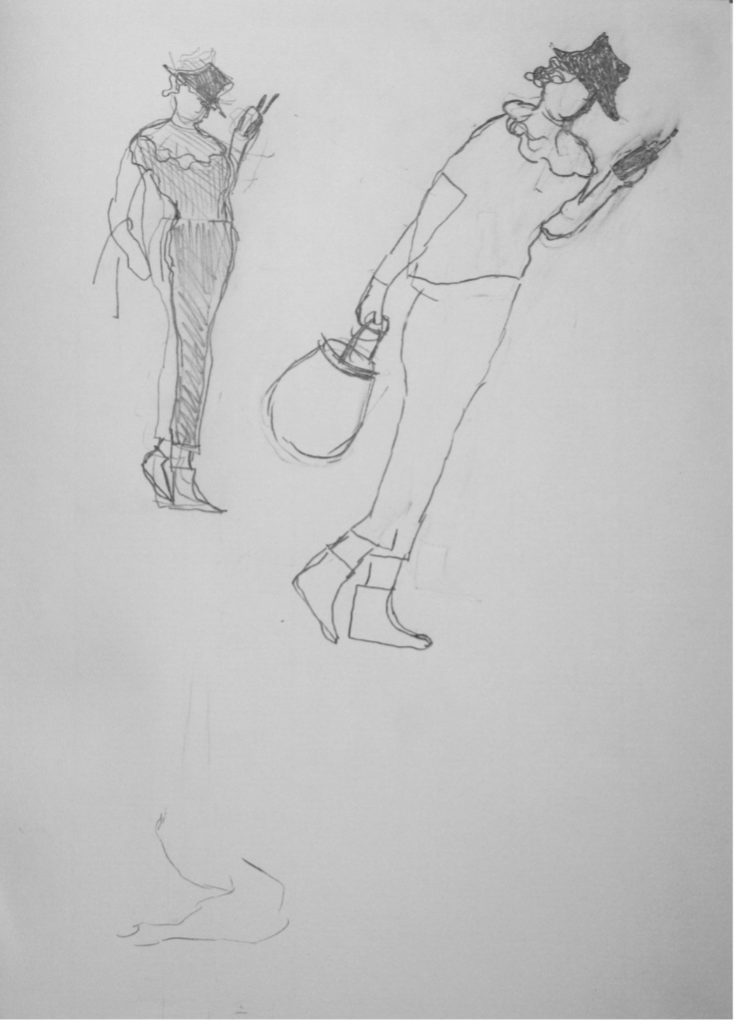

In the first instance, I trawl for images. Through a drawing response to my initial observed drawings (I don’t just dream it up, in fact I don’t invent anything), I make further drawings to re-configure these to evoke new elements and figures. By working and reworking through drawing, they become ‘real’ in my mind, maybe becoming like actors or protagonists in a play.

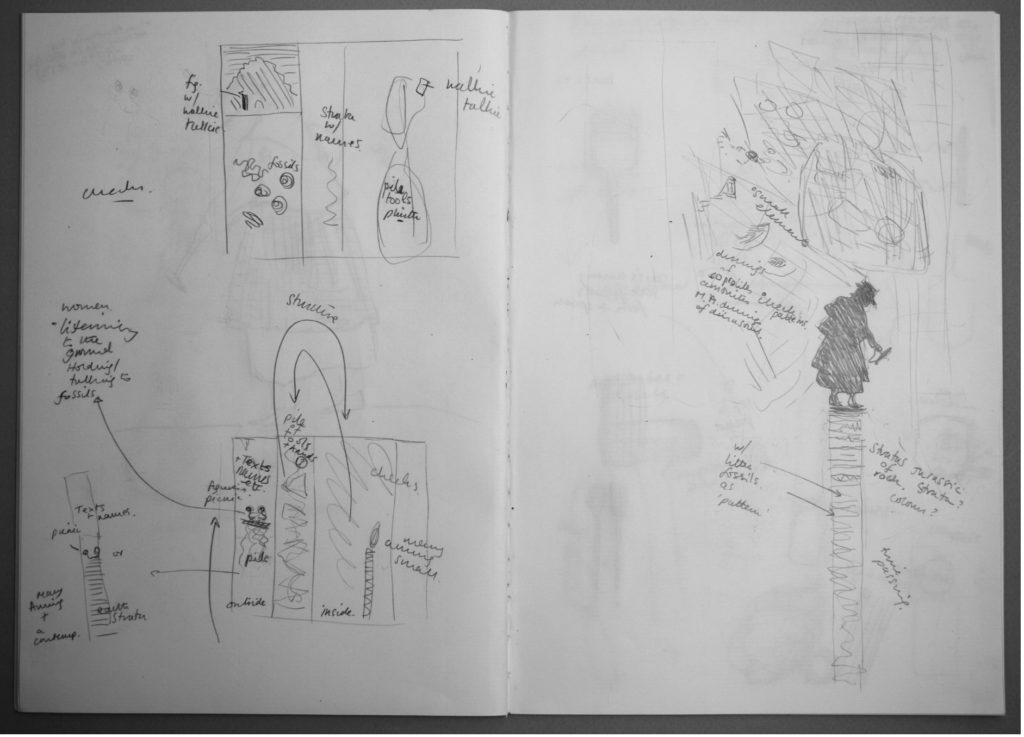

I begin with pencil drawing on sheets of paper or in drawing books, not too large, up to about 20 x 30cm. (Figures 4 & 5) I often trace these drawings with pencil and carbon paper, (sometimes I use the line quality of the carbon paper), I photograph them with my phone camera, digitally manipulate them and print them out at different sizes, sometimes enlarging them using wall projections, and tracing them back onto paper. I flip and overlay drawings to create unexpected juxtapositions. I do similar or equivalent actions in the digital space as in the analogue, studio space. During this ‘messing around’ period of trial and error, unexpected things happen and from the start, I disrupt and undermine my actions. The computer and more recently the phone camera have changed my practice though my final outputs are analogue. I work with the phone camera as if it is a drawing book, intuitively and directly. It also serves as an additional ‘sketch’ book for when I am out and about at museums etc. I select from these photos, often drawing directly from them. I draw from actual elements observed, from archives, photos and from still and moving images online. I generate patterns using the computer, something that would be unnecessarily onerous by hand. For example, I might photograph a piece of taffeta textile, print it out on paper, trace it, photograph the tracing and then re-work it on the computer to build patterns. I don’t use a pattern making programme. Although I spend time connecting the units of pattern I am drawn to the mismatch and collisions of units of patterns where they don’t connect properly.

I continually hand re-draw/copy /re-trace drawings and juxtapose individual elements together so one element is in relation to another rather than in isolation. I am interested in the changes that occur from one drawing to the next, the slippages and transformations. A drawing can go from an inert tracing to be reanimated as something quite different.

Figure 4: On the mobile phone (2020), pencil drawing, 29.7x21cm.

One of the central tenets of new materialism, agential realism, is how the object of our research is shaped or enacted by how we research it. Karen Barad writes:

[p]ractices of knowing and being are not isolable; they are mutually implicated. We don’t obtain knowledge by standing outside the world; we know because we are of the world. We are part of the world in its differential becoming. The separation of epistemology from ontology is a reverberation of a metaphysics that assumes an inherent difference between human and nonhuman, subject and object, mind and body, matter and discourse. (2007: 185)

In articulating her process, Charlotte reveals how materials and their intra-action become a determining factor in the progression of the work: reworking drawings until they assume autonomy—an existence that is distinct and separate to that of the maker: ‘like protagonists in a play;’ looking to see how shapes respond to one another, how these shapes assume new and unexpected affiliations. The material itself becomes agential; an inert tracing is reanimated and new connections are formed.

Artist and academic Charlotte Gould has remarked (2013) on how craft and new technology may initially have seemed to be counterintuitive bedfellows, yet new media has allowed for fresh advances to be made, and new collaborations to form, both in crafting communities and contemporary art practice. Online communities provide an alternative public sphere for craft activities (Bratich & Brush 2011) collapsing the traditionally private (domestic) sphere of feminine crafting while the relationship between craft and new technology also functions analogically: ‘the complexity of repetitive and extended sequences necessary in knitting and embroidering can be compared to the workings of a computer’. (Gould 2013: 30) Charlotte Hodes’ use of contemporary technology (phone camera and computer), augments—rather than replaces—analogue ways of working; her camera and computer are used to interrogate the specificity of her primary media, just as her paper and pencil allow for new uses of the camera phone and computer. Tools and technique become mutually defining in such a manner that leads us to confound categories of old versus new.

Parallel to Charlotte’s trawl for images, I trawl through online databases for fresh scholarly insights into craft and crafting techniques. I find that definitions that once seemed clear have in fact always been contested territory: binary oppositions to which society attributes greater or lesser worth are a convenient fiction whereby ‘different from’ becomes synonymous with ‘better than.’ In her introduction to Extra/Ordinary, her book on contemporary craft in art, Maria Elena Buszek notes that ‘still-lingering definitions of craft as “technical knowledge” and art as “aesthetic” or “conceptual knowledge” arguably began not with late modernism, but with the era that literary scholars call “early modern,” with the hierarchies imposed upon the arts by the High Renaissance’. (2011: 6) But these artistic hierarchies were always already subsumed by the greater social structural divide of gender. [7] For decades now, academics have explored the ways in which traditionally domestic and feminine pursuits (as well as the creative traditions of communities of colour and of artists in the developing world) tend to be dismissed as ‘craft’, as distinct from ‘art’ or ‘design’. In their ground-breaking collaboration, Old Mistresses, Women, Art and Ideology, Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock (1981) grant stitching, embroidering, and patchwork a central place in the history of women’s art. Parker goes on to explore the question in-depth, concluding that craft is a gendered issue: ‘[w]hen women paint, it is acknowledged to be art. When women embroider, it is seen not as art, but entirely as the expression of femininity. And, crucially, it is categorized as craft’. (1984: 4-5) In this binary logic, and despite William Morris, craft was devalued through its association with the feminine in opposition to ‘worthier’ and more valuable art, associated with the masculine.

For as long as I have been looking at Charlotte’s work, I have considered her techniques to derive from these feminine and domestic crafts: needlework, lacework, embroidery, quilting. Her description above of moving and flipping pieces to generate patterns, seeking the moment when the visual field coheres, is reminiscent of the process in quilt-making of juxtaposing random and leftover scraps of material, looking for that moment when unrelated patterns from different cloths come together to form a new connection. I have slotted her techniques conveniently into a feminist lineage that dates back to when these domestic pursuits (laboured and leisured) were first put to active political use by social reform movements in nineteenth century America. [8] I have also remarked upon how Charlotte’s work harks back to the 1970s, when female artists such as Faith Ringgold, Judy Chicago, Joyce Scott, and Miriam Schapiro used feminine craft objects and techniques to bring feminism and civil rights to the heart of the art world. (Westley 2016)

But then I come across British archaeologist and medieval historian Alexander Langlands’ Craeft (2017), in which he provides a discussion of the etymology of the word ‘craft.’ He explains that when the term ‘craeft’ first emerged in England during the Middle Ages, it connoted power, physical strength, and skill. However, as early as 1200, it began to mean ‘cunning’ or ‘sly’ (a meaning still retained in the word ‘crafty’). Later, perhaps due to its association with power, it also began to hint at the supernatural. It was only later still that it began to carry connotations of dexterity or detail. In semiotic logic, the signifier, here the word, is fixed, but the signified floats free, its meaning only anchored by factors external to itself. As the signified shifts, so do gendered connotations. It pleases me to know that the early meanings of craft were associated with physical strength—that masculine attribute. Many of the feminist artworks of the 1970s involved soft materials such as twine and wool (not to be confused with the 1960s movement in soft sculpture), materials that involved the intertwining or bringing together of disparate elements. It is easy, and very tempting, to compare Charlotte’s patterns to textile or lacework or embroidery. Indeed, she sources many of these patterns from collections of textiles such as the one at the Victoria & Albert museum. But when I ask Charlotte to list her tools, this is what she replies:

Pencil, scalpel, scissors, paint brush, mobile phone camera, computer, digital printer.

And I reflect that there’s nothing very soft, or squidgy, or unifying, about the line drawn by a pencil, or cut by a scalpel. Later, I ask Charlotte how she thinks the cut edge differs from the drawn line, and she replies that each are distinct in terms of experience and in effect:

In brief, the pencil has nuance in touch, thickness, tone and colour. It is an additive process. The cut line is a reductive process, and it is unchanging (as long as you use the same blade). It is more similar to a line made in a vector programme on the computer, in that without a touch tablet it does not change with pressure. The cut line is devoid of emotive energy in itself except that it is the result of a destructive action. Pencil lines can describe nuanced and modulated shapes or forms. Cut lines offer up shapes only that can be removed or added.

Lines, drawn or cut (Figure 6), are not inanimate, but imbued with properties that affect the objects that surround them—just as those objects’ properties have multiple connotations. For an artist who spends so much time with lines, I am constantly surprised by how Charlotte achieves the slippage, the spillage, the effect of dissolution in the shapes and forms she uses. In work from her series of papercuts, Walking Amongst Vessels, the female figures are alternately veiled in patterns, or partly assimilated into the background in shades of dark and light. In the painting series Surfing History, copies of historical portraits of women are juxtaposed with a contemporary female nude, who leans on or drifts over them like a phantom from the future. Recalling the hovering, sometimes nebulous figures from paintings by Nancy Spero and David Salle, Charlotte’s female figures co-exist with drapery, fashion plates, pots. She refers to her nudes as membranes: they offer a selective barrier, a filter for vision. The painter Paula Rego observed about Hodes’ painting:

[p]attern is like an incantation. You fill in whole areas compulsively like a magic doodle. It is the opposite of modelling a form. When you model a form, you have to use light and it becomes sculptural, and it implies that inside that form there are guts and intestines, ovaries and what-not if it is a woman; if you use a pattern it is one way of filling in the outline. But in Charlotte’s pictures the pattern does not stay within the outline. It overlaps and takes on an existence of its own. So you get a lack of adjustment of the object—a lack of focus—everything is pulling away from everything else. (1991)

It seems as though Charlotte’s direct engagement with the concrete contours of materials, their physical delineation, reaches its actual and conceptual limit in the representation.

My email correspondence with Charlotte has both spontaneity and restraint. As I formulate questions to ask, I find myself making previously unimagined connections. Articulating ideas in writing is another form of thinking, with its own internal structure. How has Charlotte settled on a structure for this work?

On Structure

My papercut, ‘The Palaeontologist’, is in three sections, with each section indicating a different time and place. The larger right section depicts an ‘interior’ space that contains a woman on a ‘pedestal.’ The left section depicts a ‘landscape’ space. The central panel depicts a close-up strata that records a selection of female palaeontologists through time, my own genealogy. Each section is treated differently in terms of technique and style, so each has a particular quality and ‘look.’ Therefore, one of the questions is how to both work with these three distinct sections and make them connect. You may see on the lower far left side a criss-cross collaging of white on white that spills over to the middle section. There is a lot of ‘spilling’ over and seepage across the composition that unsettles the forms and pattern. But it also connects the contrasting parts. The dots are radio waves that emanate from the large woman’s walkie talkie. These float across the middle to the left section where there is a further woman with her walkie talkie. They are based on the same figure so they are an echo of each other. They try, probably unsuccessfully, to make contact and communicate. The quote ‘Walkie-talkies help us from getting lost’ is from a blog post. This papercut and the ones in the series, focus on tools. The palaeontologist’s tools make up the pedestal. The bag that the woman holds is taken from historical images of Mary Anning. [9]

On Scale

I use hand tracing and photocopy to change the scale of the elements. As I am sure you have observed, there is a lot of detail in many areas that is in direct opposition to the large-scale nature of the whole papercut. One of my questions is how to move between the details, working close-up and the overall image. In this way, the work is different from quilting or tapestry where you can rely on the ‘known’ overall design whilst working on each section. If there is no ‘animation’ between the contrasting scales of the fragments and shapes, then it doesn’t matter what else is working, I destroy it by cutting up the entire area. This is true of the middle section that I had intended to be a watercolour. It was very flat, so I cut it into pieces and rearranged it. You can see now it is made up of watercolour-painted cut fragments. All of the letters are hand cut. I often repeat the same elements in varying scales, this repeat referring to pattern making. The tree-like element coming down from the top edge of the dotted part (middle left section) is an enlarged detail of the digital floral pattern. It is cut from plain black paper.

Charlotte requires the contrasting scales of fragments and shapes to be ‘animate’ and to connect. This sends me back to the Baradian term of intra-action, which understands agency as not an inherent property of an individual or human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces (2007: 141) in which all designated ‘things’ are constantly exchanging and diffracting, influencing and working inseparably. It is through the active engagement with her materials, tools, ideas, and technique that both the work and the artist assume their identity.

I enjoy the fact that in an exchange about the artist’s tools, we also talk about tools depicted. Charlotte’s description of the three sections (a triptych complete with a pedestal constructed of tools that are conventionally coded masculine, on top of which stands a woman) evokes the contrast between the detail and the scale. Like the zoom on a camera, or the tracking shot of a film camera, the artist must move in and out of the image to consider the focus or, in this instance, the ‘animation’ in the composition. The word ‘detail’ returns me to another gendered genealogy in art history, so clearly delineated and described by Naomi Schor in Reading in Detail, ‘[t]o focus on the detail, and more particularly on the detail as negativity is to become aware … of its participation in a larger semantic network, bounded on one side by the ornamental, with its traditional connotations of effeminacy and decadence, and on the other, by the everyday, whose ‘prosiness’ is rooted in the domestic sphere of life presided over by women.’ (1987: 4) If the ornamental in western culture was traditionally considered to be decorative embellishment, and therefore extraneous to or devoid of meaning, feminist discourse sought to rehabilitate the ornamental as sensuous, seductive, and free from the constraints of modernist austerity. (Negrin 2006: 219) Yet, as Llewellyn Negrin has contested, such recuperation of the ornamental celebrated its femininity, but continued to leave it empty of meaning, reinforcing the limitations of that earlier categorisation. She argues that ornamentation must be understood as a signifier replete with cultural values. In Charlotte’s work, the detail is neither an embellishment nor supplementary to meaning (Schor 1987: 91), rather it is constitutive of meaning. The detail signifies both as form and content: it emerges from within dominant discourse to assert its alterity. Detail and the scale of Charlotte’s work, the way it foregrounds its own decorative technique, recalls to us the labour of its production. [10] In traditional craftwork by women (lacework, crochet, embroidery, needlework samplers), detail reveals the otherwise invisible labour. Charlotte’s work seems to tease us with this notion—the labour is hidden in plain sight. Depending on how the light falls on her subtle palette, the incremental layering of paper and colour reveals itself to, or conceals itself from, the viewer. At times, the intricacy of the process discloses itself, while at other times it remains wholly hidden.

On Technique

When I ask Charlotte about the physical labour involved in her work, she replies:

The papercuts often begin with me applying largish shapes across the surface. I spend crazy amounts of time hand cutting patterns and pieces that I have hand drawn/traced and then I don’t use but they become part of my collage ‘bank’ that can be used later, at any time. I move fragments, coloured shapes and silhouettes around a lot before adhering a section and then continuing. I use my linear pencil drawings to cut flat cut colour or patterned shapes. Sometimes I cut out large sections of the papercut, reworking the entire composition. Again, all cut areas can be re-used, sometimes turned around and added as a further disrupting fragments [sic]. My technique is to cut with the scalpel, the same 10A blade always, changed at least one a day, sometimes scissors for large areas and the same adhesive (Lascaux 498) as always.

I can’t think until I have begun either drawing or collaging. And then when I am cutting an area of paper that I have decided on or sticking down fragments that are ready, it’s a different more meditative process of using my hands enabling me to think. But everything is provisional, even when its position is decided, it can be removed or re-positioned. Nothing is done ‘mechanically.’

Until now, I have used those standard green rubber cutting mats, though am very excited to have found a new type that is custom cut to size and softer, so less tough on my fingers. I pad out the scalpel blade with tissues and masking tape. It is important to get these things right. I work on the table, horizontally, but then view the work on the wall before finalising as it looks different vertically. That is a disruptive surprise too. There is a huge difference working flat or vertically in terms of your body position and weight. Sometimes, I stand at the table to work, gravity enables your arms to relax. Sitting brings my eye close to my ‘cutting’ hand and to the papercut, an intensity that blocks out the ‘world’ around.

I have become increasingly sensitised to paper, to different surface qualities and colour. Even a tiniest fragment can be tweaked or replaced.

I am very conscious of the impact of the pace of working, and always have been. And to the way the speed of working is impacted by technique. Perhaps we could discuss this point together?

Just as Charlotte’s thinking happens through her materials, so too do my arguments form as I cut, paste, and reflect upon passages of our correspondence. My pace of working is intermittent and irregular: black symbols appear on a white screen at varying speed and intensity, and I’m aware of a nagging ache in my lower back against the chair. I remember days pre-Covid when I visited Charlotte’s studio, an area filled with colourful paper, bags of collage resources, stacked canvases. The table where Charlotte does her cutting is strewn with paper. When she works with her scalpel, she sits or stands, her body inclined, her weight leaning into the repetitive gesture. The investment of the artist’s body in the production of the work of art has been explored from the Renaissance to the present day. The dominant image critiqued by feminist art historians is the body of the male artist, either standing in front of the easel (Christine Battersby 1990) or horizontally, in bestial fashion, over the work. (Pollock in Bois & Krauss 1997) In the sphere of craft, however, the crafter’s body has been largely rendered invisible—the hand acting as a synecdoche standing in for the body. Craftwork has been described as work of dexterity, deriving from the Latin ‘dexter’ meaning ‘skilful’ and ‘right hand’, and in sixteenth century French coming to mean to mean both ‘skill in using the hands’ and mental adroitness. This fetishisation of the hand, like Ahmed’s exploration of Lamarck’s blacksmith’s arm, traces a lineage of craft dexterity, a lineage that is wholly distinct from the Cartesian logic of the primacy of vision that dominated Modernist art. Dexterity, in the narrative of high modernism was, according to Greenberg, further grounds for disqualification as an artist: women were seen as skilled labourers, not artists. Greenberg states that it is, ‘not skill or dexterity but inspiration, vision, intuitive decision, [that] counts essentially in the creation of aesthetic quality’. (Auther 2004: 3)

Ahmed describes Lamarck’s blacksmith’s arm as operating like a phantom limb. Used throughout the nineteenth century as an example to demonstrate Lamarck’s principle—the law of exercise—it became forever associated with Lamarck, despite the fact that Lamarck never used the example. She observes, ‘[w]e can treat the absence of a reference to the blacksmith’s arm in Lamarck as a teachable moment; we learn how what is missing comes to matter’. (2019: 88) Similarly, the dematerialisation of the craft-person’s body in the discourse around craft that emphasises the indexical trace of the hand in the finished craftwork comes to matter when we look at images of the artist/craft-person at work. Photographs of Charlotte at work in her studio, inclined over her desk, the weight of her body behind her arm, guiding her hand, recall the seventeenth century canvases referenced by Chadwick. [11] (Figure 7) Manual labour is physical labour; the body matters, is essential matter; the final work is the result of embodied knowledge (Hodes: it’s a different more meditative process of using my hands enabling me to think). The physical labour invested in the process of cutting signifies as process; indeed, according to Charlotte, it has the effect of slowing down time and opening up contemplative space.

Craft, as we have seen, is commonly defined as an activity that is based on skill and acquired knowledge. Hodes’ commentary on her own craft reveals to me the equal importance of not knowing: I can’t think until I have begun either drawing or collaging. If the artist is working from a subject position that is both embodied and embedded in her materials, this relationship demonstrates that matter too is fluid, dynamic and, at times, unpredictable: a limited range of material holds unlimited possibilities:

The papercut is made up of printed and painted papers (some painted before cutting up and some painted into after the paper fragments have been applied) using the scalpel and sometimes scissors for larger pieces. I am acutely aware of each and every painted paper that have different physical qualities and colour to each other and to printed papers. I use many types of paper with different thicknesses, so before I even begin, I have a range of material like quilt-making. Quilt-making usually has a strict and simple structure in terms of how the shapes are stitched together (even if the design is complex). I also have a limited range of materials to work with, with unlimited possibilities within that. But in contrast, my method is intuitive, nothing is ‘designed’, the structure enables me to work spontaneously. I respond to even the tiniest fragment as I go along. I don’t conform to uniformity of size (akin to quilting). Complex quilts have systems.

The ‘cut’ of the scalpel acts as a line drawing or it produces shape, as with the sea animal form on the lower left section. This form is ‘transparent’ with a lot of detail. In contrast, the upside-down, green figure is a ‘negative’ silhouette shape, and the seaweed form bottom, far left is ‘positive.’ The little seated figure, bottom left is in two sections as if there is light or shadow across her body, dissolving her form. She is detailed and also delineated by a cut line. The dot pattern—middle part of the left section—has been re-worked over in paint (a further physical contrast).

Transparency is a significant part in terms of my language. It contrasts, I think, with ideas embedded in craft practice, of the physicality of making. The dress that the large figure is wearing; the small ‘dotted’ figure; the tools making up the pedestal are like ‘holes’ that render them useless. (Figure 2)

Matter can be added to; it can also be taken away from. As the artist works, her gestures may slow down and become repetitive. Repetitive labour engenders its own reflective rhythm and mood:

The digital print has a uniformity that I work with and against. For the ‘The Palaeontologist’ I created floral and dot patterns for the ‘ground’ surface. My floral pattern was originally hand drawn, sourced from a hand painted wall found on the beautiful house, Herregården, in Larvik, Norway. From then on, my intervention, disrupting the unified and smooth digital surfaces is analogue, hands-on in the studio.

The right section has the floral print across the entire piece. The central section has no digital print, and the left section has the dot pattern only in part. This immediately makes each section very different; they can never merge. The pattern on the right side has been cut into with the same pattern (papers of varying oranges placed underneath). It is a kind of stitching (btw I hate sewing).

Cutting the pattern into a large area is repetitive. I draw it out on the back of the paper and cut it from the back, so I have a guide. (Btw the cut edge made from the back of the paper has a different quality from when it is made from the front.) I make decisions about what to remove, but it is quite a meditative process—I feel a change in mood. It opens up a thinking space for me to consider the decisions that I may make next with the papercut and the connections between the ideas.

I think of the papercut in terms of drawn marks. It is important how the fragments are juxtaposed both beside each other and on top as well as the contrasting scales.

Sera Waters (2012) has explored the notion of repetitive crafting in a discussion of how it changes the relationship not just between body and materials, but also between the artist and their sense of lived time. Waters argues that these repetitive gestures have connective power: obsessive gestures become investigations into contemporaneity and time. In working with, and building upon, the materiality of the everyday as well as the monotony of habit, routine and gesture, she argues that repetitively crafted works shift from critiquing culture from without, and instead build connections from within. Charlotte’s repetitive labour, the investment of her body in a time-consuming process, interrupts the inexorable motion of linear time. This is another point of conjunction between Charlotte’s work and the current craftivism movement, which posits ‘slowness’ as a form of resistance. Charlotte’s engagement with materials is deliberately, thoughtfully, contemplatively slow. The traces of this temporality in her technique are thus visible to the viewer. This temporal delay is experienced by and through the artist, and is materialised in the work that connects the maker and the spectator. The temporal delay inserted into the viewing experience of Charlotte’s work reflects or echoes the temporal delay inserted into her process. The time invested in the physical labour, her crafting process, becomes part of the spectator’s experience of time. Beholding a large or a small-scale work by Hodes demands close attention. I go back to my own papercut (Figure 1) and notice how the colour and forms send my eyes in different directions over the paper: the observation of detail demands detailed (slow) viewing.

In his exploration of craeft, Langlands observes how craft techniques change our engagement with the material world in such a way that our relationship to it is also altered. In the original sense of the word ‘craft’, knowledge, wisdom and resourcefulness pertain to the way this material engagement (knowledge of one’s materials) gives rise to an understanding of how objects and systems are built, and how they fall apart. In the definition of craft that involves its functionality, there is an active relationship between object and other, which makes redundant the word viewer, spectator, or audience. Traditionally the crafted object is destined to be used, touched, handled: from the maker’s hands to the user’s hands, interpretation of the object involved tactility, an active engagement with the object. We might argue that there is no such thing as the passive contemplation of a work of art. For Jacque Rancière’s ‘emancipated spectator’, interpreting the visual field is a means of transforming it or reconfiguring it; the spectator is always already active. (2011: 13) I would argue that the craft inherent in Charlotte’s art foregrounds this active spectatorship. The viewing experience of Charlotte’s work is bound up in the history of its making: the detail that is revelatory of the process situates a viewing experience that signifies diachronically (through time) as well as synchronically (in the simultaneous visual apprehension of the image). If craftivism has gained popularity in reaction to the speed and economics of a dematerialised capitalist system, the viewing experience demanded by Charlotte’s work similarly valorises an alternative conception of embodied time and material engagement. Subjective time is contingent upon the artist’s relationship with her materials, how those materials act upon one another, and how this action is reanimated in the spectator’s experience of the work.

In the space between the visual and verbal opened up by my exchange with Charlotte, it has become clear that the phenomenology of process in the artist’s work signifies within a complex network of discourses. Moving away from notions of old materialism, whose Cartesian epistemology considered matter to be inert or passive, towards the new materialism, which posits matter as dynamic and relational, we must start to think about how the material properties of the finished work embody their coming-into-being, and how these objects intra-act within multiple discourses to create a space where identities are shifting and unstable, where the old dualisms (craft/art, masculine/feminine, object/subject, mind/matter) collapse and epistemological conventions are interrupted to open up new spaces for signification.

Notes

[1] Papercutting is an artistic technique that involves the cutting and combining of shapes from paper. The cutting can be performed with a variety of tools, including scissors, scalpel or laser. Papercuts, collage and montage have a long history in the work of women artists, notably Hannah Hoch (1889-1978), Anne Ryan (1889-1954), Pauline Boty (1938-1966) and Barbara Kruger, as well as, more recently, the cut-out silhouettes of Kara Walker and the collages of Wangechi Mutu. For further reading on how collage and papercuts have known a recent revival in contemporary art, see ‘Cut and Paste: Charlie White on the Collage Impulse Today’, History of Photography, 2019-04-03, vol. 43 (2), pp. 122-129.

[2] For further reading on how art historical discourse has traditionally obscured the craft involved in the making of art, as well as the artistic qualities of craftwork, see Sally J. Markowitz on ‘The Distinction between Art and Craft’ in The Journal of Aesthetic Education (1994).

[3] For a nuanced discussion of the complex relationships between skilled artisans and factory manufacture during the Industrial Revolution, see Glenn Adamson’s The Invention of Craft (2013).

[4] ‘Intra-action’ is a term coined by Karen Barad to replace ‘interaction.’ If interaction involves pre-established bodies that participate in action with each other, intra-action understands agency as not an inherent property of an individual but as a dynamism of forces (Barad, 2007: 141) in which all things, including matter, work together.

[5] The use of ceramics in the art world has recently come back into the spotlight through work by artists such as Ai Weiwei, Anish Kapoor, Sterling Ruby and Jennie Jieun Lee. However, while these ceramics might be exhibited as part of multimedia installations, few artists (with the notable exception of Andrew Rafferty) are combining ceramic ware in/onto their canvases.

[6] An expression first popularised by the nineteenth century Romantics in a desire to detach art from an increasing stress on rationalism and the fear that art should or could become utilitarian. The concept had an afterlife in twentieth century high modernist theories of Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried.

[7] See Whitney Chadwick’s account of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, where women’s work was not categorised by division into arts and crafts or their attendant genres but lumped together in a single display area. (1991: 211)

[8] The political activism that is the legacy of such crafting reaches its apotheosis in today’s craftivism (Greer 2014), as explored by such scholars as Heimerl a& Levine (2008), Gauntlett (2011), Bratich & Brush (2011) and Bryan-Wilson (2011 & 2017).

[9] Mary Anning, 1799-1847, an English fossil collector, dealer and palaeontologist, is one of the names mentioned in the central column of Hodes’ piece.

[10] For an art historical contextualisation of the representation of female labour in craftwork, see Whitney Chadwick’s (1991) analysis of seventeenth century Dutch genre painting, which included descriptive domestic scenes of women engrossed in the activities of needlework, sewing, embroidery, and lacemaking. Female artists of the time, she observes in reference to the work of Geertruid Roghman, emphasise the labour of these crafts over their decorative element, which receives the main focus in male contemporaries such as Vermeer and Caspar Netscher. ‘Roghman’s figures are often in strained poses with their heads bent uncomfortably close to their laps as if to stress the difficulty of doing fine work in the dim interiors of Dutch houses of the period. Surrounded by the implements necessary to their activities- spindles, combs, bundles of cloth and thread—they demonstrate the complexity and physical labour of the task’ (Chadwick 1991: 115).

[11] Hodes’ multimedia work also includes printmaking, a process which similarly involves being bent over the plate, stone, or screen as well as the printing bed of the press.

REFERENCES

Adamson, Glenn (2013), The Invention of Craft, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ahmed, Sara (2019), What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use, Durham: Duke University Press.

Auther, Elissa (2004), ‘The Decorative, Abstraction, and the Hierarchy of Art and Craft in the Art Criticism of Clement Greenberg’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol 27, No. 3, pp. 341-64.

Barad, Karen (2007), Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham: Duke University Press.

Battersby, Christine (1990), Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bois, Yves-Alain and Rosalind Krauss (1997), Formless: A User’s Guide, New York: Zone Books

Bratich, Jack Z. and Heidi M. Brush (2011), ‘Fabricating Activism, Craft-Work, Popular Culture, Gender’, Utopian Studies, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 233-260.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia (2011), Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, University of California Press.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia (2013), ‘Eleven Propositions in Response to the Question: “What is Contemporary about Craft?”’, The Journal of Modern Craft, 6:1, pp. 7-10.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia (2017), Fray: Art and Textile Politics, University of Chicago Press.

Burger, Peter (1984), Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Buszek, Maria-Elena ed. (2011), Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, Durham: Duke University Press.

Chadwick, Whitney (1991), Women, Art, and Society, London: Thames and Hudson.

Duchamp, Marcel, Henri Pierre Roché & Beatrice Wood (May 1917), ‘The Richard Mutt Case’, The Blind Man, no. 2.

Gauntlett, David (2011), Making is Connecting. The Social Meaning of Creativity, From DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0., Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gould, Charlotte (2013), ‘Crafting the Web: New Media Craft in British and American Contemporary Art’, InMedia http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/673 (last accessed 1 February 2021).

Greer, Betsy (2014), Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism, Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Heimerl, Cortney & Faythe Levine eds. (2008), Handmade Nation, The Rise of DIY, Art, Craft, and Design, New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Langlands, Alexander (2019), Craeft: An Inquiry Into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts, London: Faber and Faber.

Markowitz, J. Sally (1994), ‘The Distinction between Art and Craft’, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 55-70.

Morris, William (2018), Hopes and Fears for Art: Five Lectures Delivered in Birmingham, London, and Nottingham, 1878-1881, Victoria: Leopold Classic Library.

Negrin, Llewellyn (2006), ‘Ornament and the Feminine’, Feminist Theory, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 219-235.

Parker, Rozsika & Griselda Pollock (1981), Old Mistresses, Women, Art and Ideology, London: Pandora.

Parker, Rozsika (1984), The Subversive Stitch, Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, London: The Women’s Press.

Ranciere, Jacques (2011), The Emancipated Spectator, New York: Verso Books.

Rego, Paula, in Conversation with Francesca Rossi (1991), http://charlottehodes.com/text/paintings-1991-1992-eagle-gallery/ (last accessed 20 January 2021).

Risatti, Howard (2007), A Theory of Craft, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Robertson, Lisa (2020), The Baudelaire Fractal, Toronto: Coach House Books.

Roche, Henri-Pierre, Beatrice Wood, and Marcel Duchamp eds. (1917), Blindman, New York.

Schor, Naomi (1987), Reading in Detail: Aesthetics and the Feminine, London: Routledge.

Waters, Sera (2012), ‘Repetitive Crafting: The Shared Aesthetic of Time in Australian Contemporary Art’, craft+ design enquiry, No.4, p. 69.

Westley, Hannah (2016), Now You See Me: Self-representation in the Work of Charlotte Hodes, London: London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London.

White, Charlie (2019), ‘Cut and Paste: Charlie White on the Collage Impulse Today’, History of Photography, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 122-129.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey