Young Women and Alcohol in Lise Myhre’s Nemi

by: Adriana Margareta Dancus , March 30, 2023

by: Adriana Margareta Dancus , March 30, 2023

Lise Myhre (born 1975) is a legend of Norwegian comics. She is the creator of Nemi (1997-), one of the most popular comic strips in and from Norway. It is syndicated as a daily strip to approximately 150 newspapers, magazines, and websites in and outside the Nordic countries by media group Bulls Press (Holen 2021). First released in 1997 as an alternative series with the original title Den svarte siden [The Dark Side/Page], Nemi came into the mainstream spotlight at the beginning of the 2000s, running daily in some of the largest newspapers in the Nordic countries, gaining its own magazine in 2003, while 17 collections have been released in the period 2004-2021 (Gisle and Hole 2021). The main character of the series is Nemi Montoya, a young woman in her twenties, with sexy curves and long, black hair who dresses like a goth [1], and loves metal and hard rock music, books, chocolate, and dragons. Nemi is a complex character with at times conflicting traits: socially engaged, civic minded, determined, naïve, childish, pensive, brutally honest, impulsive, cynic, romantic, funny, and dreamy. She is also a dedicated friend, a loner, a fierce advocate of animal rights, an outsider who struggles to keep a job, and a young woman who has innumerable sexual partners until she meets Grimm, a muscular man with long, black wavy hair who shares her taste in music. Nemi can usually be located in Oslo pubs, where she occasionally drinks too much, often accompanied by her best friend Cyan.

Myhre’s Nemi affords important reflections on gender from the perspective of a young, cis-gendered, white female character. [2] While Nemi does not question her womanhood, she does challenge conventional ideas of femininity, here understood as ‘a construction of socially sustained performances and repetitive acts’ (Romu 2022: 17). Asked to reflect on how it is to be a woman cartoonist, Myhre has pointed out how many readers expect Nemi to be a role model and so are troubled by her swearing, sex life, drinking and smoking (Myhre 2004, Riesto 2004). A common request Myhre has received from concerned readers is that Nemi drink less, have less—or clearly safe—sex, and stop swearing and smoking (Myhre 2004: 122). In this article, I am particularly interested in how Myhre depicts Nemi’s drinking habits, and how these depictions resonate in a cultural and socio-political context. What kind of insights into young women’s drinking cultures does Nemi give readers? How does Myhre use the cliché of the drunk woman to promote a feminist agenda?

I begin by placing Nemi in the contemporary landscape of Norwegian comics and provide statistics and reflections on women’s alcohol consumption in Norway. I then perform close readings of two short stories which mark important points in Myhre’s Nemi authorship, which to date extends over a period of twenty-five years: the first Nemi story longer than a page, published in the summer of 2000 in the first Nemi album, and the short story ‘Halvt ett, og fortsatt prinsesse’ [‘Half Past One, and Still a Princess’] published in the Nemi Christmas album in 2005, which was a commercial bestseller in the history of Nemi comics (Gisle and Holen 2021). I tie both short stories to other comic strips published in the same period and collected in Nemi: enhjørninger og avsagde hagler (2004, Nemi: Unicorns and Sawed-off Shotguns), which gathers early Nemi comics released in the period 1997-2000, Nemi: Princess of Darkness (2012), which is a collection of Nemi comics from the top-selling years 2005 and 2006, and selected strips from 2010 gathered in Nemi: Med Grimm og gru (2016, Nemi: With Grimm and Horror), in which Nemi goes through a significant change in her life as she and Grimm get together. By choosing comics from 2000, 2005 and 2010 respectively, the article aims to provide a historical perspective on Myhre’s Nemi comics.

Lise Myhre’s Neminism

In the first Nemi book, released in 2004, Myhre explains how Nemi was a turning point in her own life. Myhre was 21, working as a bartender, illustrator, book consultant, graphic designer, cleaner and cartoonist, and about to give up comics when Nemi showed up: ‘A human girl in a goth environment: a figure I had much more in common with than my earlier crocodiles with ties, a girl I could illustrate with credibility’ (Myhre 2004, 3). [3] Nemi quickly grew in popularity. In retrospect, Myhre’s success is quite extraordinary, bearing in mind that American comics saturated the Norwegian market up until the mid-1980s (Birkeland, Risa, Vold 2018: 366). Together with Norwegian comic strips like Pondus (Øverli 1995-), Eon (Lauvik 1998-) and Radio Gaga (Sagåsen 2001-), Nemi broke the monopoly of American comics and paved the way for much greater sales and awareness of Norwegian comics in the 2000s. By 2018, almost 40 per cent of the comics published in Norwegian newspapers were Norwegian in origin—however, only four out of 50 comic strips published in Norway’s main newspapers were created by female cartoonists (Espe 2018). [4] In the 2020s, large Norwegian newspapers have further opened the door to several other women cartoonists from Norway, such as Hanne Monge Sigbjørnsen aka Tegnehanne, Therese Eide, Linn Irene Ingemundsen and Ingrid Bomann-Larsen (Sätre 2019), which testifies to an increased gender-awareness in the Norwegian comics scene.

In the Norwegian media, Myhre is commonly asked to share her experiences as a woman cartoonist in a male dominated industry, and occasionally she is met with derogatory and sexist language. For example, in a 2002 interview with the daily newspaper Dagbladet—in which Nemi has been published since 1999—the male Norwegian journalist asked Myhre whether Nemi was ‘a babe or a bitch,’ to which Myhre immediately snapped: ‘Is this what one can choose from as a woman?’ going on to underscore her character’s complexity: ‘Her [Nemi’s] strength is that she has several more facets than old standard female characters [in comics] … She is not at all a bitch. “Bitch” is a word with negative connotations’ (Sørensen 2002). In 2002, Myhre clearly distanced herself from the feminist tradition of reclaiming derogatory terms like ‘bitch,’ which Finnish feminist colleagues, for example, proudly adopted for reasons of empowerment throughout the 2000s (Romu 2022: 13, 20).

Almost twenty years later, Myhre is still publicly challenged to defend Nemi as something else than a bitch or a babe. In a 2020 debate about the lack of diversity in Norwegian comics, Norwegian cartoonist and illustrator Sigbjørn Lilleeng deplored how women characters were depicted as insipid and boring (Pang 2020). Perhaps surprisingly Lilleeng cites Nemi as an example of that:

Nemi checks off women’s representation in terms of numbers, but she [Myrhe and by extension Nemi] is very fond of making fun of blonde ‘bimbos’ with thin waists and big boobs. Apparently without noticing that Nemi is a black-clad mirror image of them, with equally big boobs and thin waist, no matter how much chocolate she eats. (Lilleeng quoted in Pang 2020)

Once again, Myhre is put in the position of defending Nemi as something other than a female cliché. She dismisses Lilleeng’s accusations, pointing out that ‘she [Nemi] is important to many. It’s the wrong place to kick,’ and adds ‘as an outsider, Nemi has opened fire at impossible ideals and thoughtless idols … I don’t think I have made blonde jokes in the last fifteen years, but I stand by those that were written for, and in their own time’ (Pang 2020). This and the previous example from the Norwegian media illustrate how Myhre’s comics pose difficulties to more than just concerned readers who want Nemi to cut down on swearing, drinking, smoking, and sex. Nemi is difficult to categorise, and Myhre’s comics are full of paradoxes—especially regarding gender construction.

The contradictions at play in Myhre’s comics are interesting to ponder from the perspective of the gender equality discourse in Norway. Both at home and abroad, Norway is regarded as a ‘bastion of gender equality’ (Ishii-Kuntz et al. 2022: 2), commonly holding top three ranking in global gender equality statistics, such as the United Nation’s Gender Inequality Index (United Nations Human Development n.d.) and the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum 2022). There is wide support for feminism and gender equality policy among the population of Norway, with the great majority agreeing that women should work, and men should take an active role in the domestic sphere (Kitterød & Teigen 2021). On the other hand, the Norwegian labor market is highly gender-segregated along occupational lines, and Norway is one of the countries with the largest gender gaps in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education (Ishii-Kuntz et al. 2022: 2). According to a report from 2014—based on interviews with approximately 4500 men and women in the age group 18 to 75—the prevalence of lifetime rape was significant among women in Norway (9.4 per cent), while 29 per cent of the women who responded had never told anyone about their rape (Thoresen & Heimdal 2014). Stereotypical understandings of rape, sexual harassment, and other forms of sexual violence regularly surface in public debates in Norway (see Bitsch 2012), while closed men’s groups on social media argue that gender equality policy has gone too far in Norway, and use the Internet to spread anti-feminist and misogynistic agendas (Stave 2021). Myhre’s Nemi comics tap into these particularly Norwegian paradoxes and tensions.

In addition, Nemi opens dialogue with developments in female-created comic strips from elsewhere. Analysing popular American comic strips by women from 1976 to the present, American comics scholar Susan E. Kirtley points out how these strips display contradictions which both challenge and reinforce perceptions of womanhood and female domesticity (2021: 5). After analysing a large pool of comics, Kirtley also concludes that few female-created comic strips argue for change (2021: 234). Female characters are eventually tamed and/or turned into ungrateful shrews after marriage, and the comic strips ‘largely ignored social and cultural trends, clinging to outdated ideals and a simulacrum of wholesome domesticity’ (2021: 22). These contradictions aside—which Myhre shares with her American counterparts—Nemi stays true to herself throughout the years, neither tamed nor bitterly married. Besides, Nemi abounds in references, which indicates that Myhre is very much in tune with cultural, social, and political trends—highlighting, for example, feminist and environmental issues (Huntebrinker 2020).

Myhre’s feminist project is however not anchored in theoretical discussions of patriarchy or didactic information about gender issues, as in the comics of the Swedish cartoonist Liv Strömquist (Frangos 2020). Neither does Nemi have a primary focus on recognising gender hierarchies and empowering women by showing examples of resistance and ridiculing gender essentialism, as can be seen in Finnish women’s comic magazines of the 1990s and 2000s (Romu 2020). In an email to Myhre, a fan once opined that the series deserved its own -ism: ‘neminism’—a pledge for women to do less of what others expect. and to dare to be themselves (Brandvold 2005). From this perspective, it is particularly interesting to investigate Nemi’s relationship with alcohol, which many readers contest, because alcohol is commonly thought to have an un-inhibiting effect on the consumer, making them care less and have less control over their actions. Before I turn to close readings of selected material from Nemi, a few considerations on the relationship between women and alcohol in Norway must be put forward.

Women, Alcohol & ‘Fylleangst’

Norwegian sociologist Edle Ravndal (2008) discusses how challenging it can be to say something conclusive about Norwegian women’s alcohol consumption based on existing statistics, except the fact that Norwegian women today drink more and in far more situations than before (Ravndal 2008: 61-2). Ravndal also points out that although men continue to top the alcohol statistics in Norway, it is often women’s relationship to alcohol that triggers the biggest concern among researchers and public opinion (Ravndal 2008: 38, 53). She even identifies five myths about women’s relationship to alcohol that have historically coloured research as well as public debate: 1) the woman who hides her addiction and drinks in silence (‘the Mona Lisa’), 2) the sinful female addict who prostitutes herself, 3) the completely destroyed woman for whom treatment can do little, 4) the active and double-employed professional woman who uses alcohol to decompress, and 5) the good mother whose strong caring instincts steer her away from drinking (‘the Madonna’) (Ravndal 2008: 41).

Another recent Norwegian study based on four large surveys of women of different ages (15-20, 21-30, women students at the University of Oslo aged 20-35, and adult women aged 15+) points out that the number of women who drink heavily has gone up in all age groups (Vedøy & Skretting 2009, 31, 44, 52, 59). Women in Oslo drink more than in the rest of the country (Vedøy & Skretting 2009: 7), while women under thirty drink more than women in the age group 31-60 (Vedøy & Skretting 2009: 60). The same study finds a correlation between Norwegian women’s increased alcohol consumption and higher risks of liver damage and cancer, injuries, accidents, fights and quarrelling, unwanted sexual attention, and problems at work and school (Vedøy & Skretting 2009: 8 & 61).

While this research relies primarily on quantitative methods, the Norwegian sociologist Eivind Grip Fjær has conducted in-depth interviews with young social drinkers of both genders from Norway. Particularly interested in how youths evaluate their behaviour the day after heavy drinking, Fjær highlights the experience of fylleangst. Fylleangst and fylleångest are unique Nordic terms that exist only in Norwegian and Swedish respectively. They are compound words combining ‘fyll’ (binge/alcohol intoxication) and ‘angst’/ ‘ångest’ (angst). Both refer to a perceived anxiety following heavy drinking. Fylleangst is not the same this as a hangover, for which Norwegian has a separate word: fyllesyke (binge sickness). While the symptoms of fyllesyke are physiological (headache, dry mouth, vomit, dizziness), fylleangst is a rather vague affective response which Fjær in his research analytically translates into the moral emotions of guilt, shame, and embarrassment (for the want of a more precise English term).

As Fjær proceeds to analyse his interview data, he points out a limitation of his study: in the informants’ accounts, guilt, shame, and embarrassment blur into one another, which makes it difficult for Fjær to decide precisely which of these three emotions was most prominent. Fjær sees this limitation as being a result of a methodological choice, which ‘future studies can avoid by including more precise operationalizations in their research designs’ (309). I suggest it is not so much the research design that was the problem, as much as the process of cultural translation that Fjær initiated. Fylleangst is not the same as shame, guilt, and embarrassment, which explains why Fjær could not ‘decide precisely’ which of these moral emotions featured in the specific interviews he conducted.

Instead, I propose conceptualising fylleangst through the concept of ugly feeling, as introduced by American literary scholar Sianne Ngai (2005). According to Ngai, ugly feelings are ambient, non-cathartic, intentionally weak and politically ambiguous emotions that are particularly able to diagnose situations that are ‘marked by blocked or thwarted action’ (2005: 27). Envy, paranoia, irritation, anxiety, ‘stuplimity’ (a combination of stupefaction and sublimity), and disgust are the ugly feelings Ngai discusses in detail through close analysis of various literary works. I argue that fylleangst is a Nordic ugly feeling with gender dimensions, as discussed by (amongst others) Norwegian journalist Marian Godø (2008) in the first chapter of a non-fiction book meant to disrupt and transgress female shame.

Godø’s chapter suggests fylleangst is a common experience among women in Norway in the 2000s and is closely tied to female shame. [5] The Norwegian women interviewed by the journalist testify to the various ways fylleangst can manifest the day after heavy drinking: mental lists of embarrassing or forbidden things what one may or could have done while inebriated, annoying inner voices, flashbacks and random sentences that pop into one’s head, fear of contacting and meeting others, panic mixed with paranoia every time a new message appears on one’s phone, a general sense of disorientation, distrust, grief and loss of control (Godø 2008).

Godø’s discussion is laudable for the way in which it describes the ugly feeling of fylleangst felt by her female informants. The extent to which Godø succeeds in her feminist project of minimising female shame and making women care less in relation to moral codes and norms for female behaviour while inebriated is, however, debatable. Godø’s choice to mix own reflections with quotes from anonymised female informants thins out her feminist agenda, and the book was only printed in a limited edition. In comparison, Nemi, and implicitly Myhre’s neminism, are both condensed and have broad public appeal, which puts the comics series in a particular position not only to give insights into young women’s relationship with alcohol, but also to change perceptions of womanhood.

Alcohol is a recurrent motif in popular comic strips from Scandinavia—for example in the Norwegian Pondus or the Swedish Rocky (Kellerman 1998-2018), both of which focus on male friendships. In the Nemi comics, the perspective is female, for nowhere is Nemi more at home than in the pub with a beer or a glass of wine next to her. In the following analysis, I will investigate Nemi’s relationship with alcohol, as well as the ugly feeling of fylleangst which regularly overwhelms her.

Nemi, Alcohol & Treatment

The first Nemi story longer than one page is rendered in black, white and shades of grey in the first Nemi book, and comprises ten pages (Myhre 2004: 99-108). On the first page of the story, eights panels of various sizes are structured along three rows. We see Cyan happily entering a bar, where Nemi has been drinking since ‘four o’clock,’ ‘Yesterday,’ as she adds. Cyan becomes visibly irritated and expresses her concerns for her friend’s mental health. Then she drags Nemi out of the bar in the hope of ‘fixing’ her. On the third row of this first page (Figure 1), Myhre uses a large panel to show the chaotic, noisy, and filthy world outside the bar and which Nemi meets with an angry face, grinding teeth and a sarcastic exclamation, ‘The world!’ (Myhre 2004: 99).

If Nemi is a woman of few words, passive and seemingly content up until Cyan drags her out of the bar, she is for the rest of the story enraged, very vocal and in full control. She grabs Cyan by the collar and screams into her face: ‘This is why I never go out before it gets dark. To avoid crashing auras with ladies in fur and fanatic joggers. Why are you doing this to me?’ (Myhre 2004: 100, bold in the original). ‘There is someone I want you to meet,’ says Cyan. After a short quarrel, Cyan uses chocolate to bribe Nemi into her car, and the two women go to meet Cyan’s father, a bald man with a white beard and small round glasses who works as a psychologist. The sign on the door reads ‘Dr. Fraud,’ a wordplay that pokes fun at Freudian psychoanalysis and sets the tone for the rest of the therapy session. Dr. Fraud immediately offers Nemi pills of various kinds, subjects her to Rorschach test, attempts hypnosis, and finally—at Nemi’s suggestion—invites her to talk.

In the next fifteen panels, Myhre uses irony as a tool to disrupt conventional understandings of gender and female madness and incites readers to accept Nemi’s perspective. She juxtaposes Nemi’s answers to Dr. Fraud with visual representations of what Nemi does. The contrast between Nemi’s rhetoric and practice has a humorous effect. ‘But you drink?’ asks Fraud. ‘In moderation,’ answers Nemi, a verbal exchange that is illustrated with a frontal shot of Nemi from the breasts up, pouring tequila and salt directly from the containers into her wide opened mouth (Myhre 2004: 105). ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ asks Dr. Fraud. ‘Well, not one, no,’ answers Nemi, in a different panel that shows her cuddling in bed with five other people and then four panels that illustrate her last dates: a punk, whom she describes as normal, a man with long hair, puffy eyes, a cigarette in his mouth and a yoyo in his hand, whom Nemi describes as healthy, a courteous boyfriend, who is screaming out loud, and finally, a generous boyfriend, who is depicted as Scrooge McDuck. When Dr. Fraud asks Nemi about her clothing style, she can no longer pretend and explodes: ‘Listen, I smoke and drink every day, have frequent sex with men I don’t know, I rarely wake up before four and I have never kept a job for more than a month’ (Myhre 2004: 107). After proclaiming the right of ‘confused’ people to be right, Nemi repudiates a life of routine, boredom, and economic stability which she accuses Dr. Fraud of leading. On the way out, she lights a cigarette, declares herself mentally sane, and drags Cyan out of the doctor’s office in a similar fashion to the way in which Cyan dragged her out of the pub, commenting: ‘And you say that I am wasting my days’ (Myhre 2004: 108, bold in the original).

This short story gives important insights into Nemi’s relationship with alcohol. For Nemi, alcohol is neither an ice breaker nor a type of social glue. She drinks alone at the bar day in and day out in what appears to be an attempt to escape the noise, filth, dysfunction, and unfairness of the outside world. Once dragged out of the bar, and still clearly inebriated, Nemi is neither empty-headed, nor completely lost. That treatment can do little for her points to the inefficiency of the psychiatric system rather than Nemi’s destructive addiction. She turns roles upside down when she emasculates Dr. Fraud and reveals him as a failed psychologist pushing pills and using outdated, dubious, and standardised methods of therapy and a set of predictably superficial questions for discussion.

The short story also witnesses contradictions and unresolved tensions. On the one hand, Myhre uses her line to disrupt Ravndal’s five myths of women and alcohol (2008: 41). Nemi is neither a Mona-Lisa nor a Madonna, neither sinful and destroyed nor a double-employed professional woman needing to decompress. In an early strip, Nemi explains to a woman at the pub, leaning against the table and with an angry face: ‘“I was drunk” is shorthand for “I threw away all inhibitions and did precisely what I wanted to,” and if you provoke me, I will do it again’ (Myhre 2004: 47). Nemi feels provoked when others question her lifestyle—including her drinking habits—and at Dr. Fraud’s office, she is in full control.

On the other hand, the short story reinforces gender stereotypes and gendered behaviour. Loud screaming and irrational female quarrelling characterise Nemi and Cyan’s interactions. Nemi’s craving for chocolate is stronger than her will, for it only takes a bar to bribe Nemi into Cyan’s car. During the Rorschach test, Dr. Fraud shows Nemi various ambiguous forms in the inkblots, to which she provides quite unexpected and, at first, reluctant interpretations. When finally shown an erect penis, Nemi puts a big smile on her face and the accompanying speech bubble contains just an ellipsis. Nemi’s quiet and happy reaction to the penis hints that she is more emotionally in sync than her previous farfetched interpretations may have suggested. Using an erect penis to confirm a woman’s sanity is a cliché that Myhre bolsters even as she advocates for women’s right to have multiple sex partners and explore their sexual drive.

There is also something very vulnerable about Nemi drinking alone in the bar and scolding Dr. Fraud for wasting his best years at the library and his money on things that are not ‘cool’ (Myhre 2004: 107). Cyan’s genuine concern for her friend and suspicion that Nemi is deeply depressed is not resolved in the story, although she seemingly comes out of the confrontation with the psychiatric system which Dr. Fraud represents on top. Myhre’s use of irony and parody tones down Nemi’s anxiety, but the noise, unfairness, and dysfunctionality of the world Nemi meets outside the bar has interesting parallel in another black-and-white strip published in the first Nemi book (Myhre 2004: 147).

This strip consists of four equally sized panels arranged two-by-two on the page. It is a concise and effective representation of Nemi’s fylleangst through what American comics scholar Elisabeth El Refaie calls a verbo-pictorial metaphor. [6] In the first panel, Nemi is surrounded by a shaming and alien-looking crowd. In the next panel, Nemi has entered a war scene reminiscent of apocalyptic films (Figure 2). There are clear similarities between the mob in this four-panel comic strip and the noisy and dysfunctional world outside the bar in the short story discussed above. While the war metaphor in the comic strip captures how Nemi’s fylleangst feels, the short story alludes to the reasons why Nemi experiences this unnerving feeling besides the more obvious alcohol intoxication: an overarching depression at the unfairness and ugliness of the world where people rush by, crash into, and exploit each other.

Nemi’s fylleangst in the short story bears witness to a situation marked by blocked and frustrated action. Nemi is unable to leave the bar until Cyan drags her out. Cyan’s attempt to put her friend into therapy is aborted, as the therapy session turns out to be a complete waste of time, although it indeed sobers Nemi up. In the four-panel comic strip, Cyan’s intervention is presented as much more auspicious. When Cyan joins Nemi, Nemi grabs her desperately by the t-shirt and begs for help. When Cyan innocently asks, ‘Binge nerves?’ the violent mob is no longer in the background of the panel (Myhre 2004: 147). This suggests the importance of Nemi and Cyan’s friendship when dealing with fylleangst. In the later Nemi comics, the Nemi-Cyan duo drinking together and helping each other through fylleangst becomes more and more common. An illustrative example of that is the short story ‘Half Past One, and Still Princess’ from the 2005 Christmas album. I want to turn attention to this story, which adds new layers of complexity to the relation between women and alcohol in the Nemi universe.

Fylleangst, Faith & Growing up

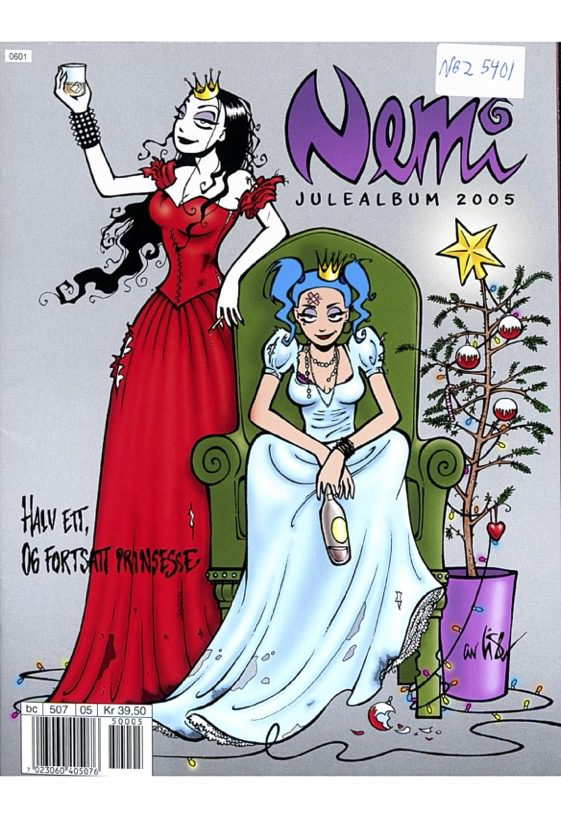

The cover of the 2005 Nemi Christmas album shows Nemi and Cyan in a familiar situation: the two friends drinking heavily together (Figure 3). The first page of the short story shows Cyan waking up in panic on a bus in a parking lot in Germany. On the second page, the emotional and colour palettes shift abruptly: from panic to melancholia and sadness; from strong complementary colours (blue, yellow, red, green) to pastel shades of mostly blue and violet. Nemi is in the company of her imaginary friend Mornon, a red goblin with tail and horns who gradually fades into grey and vanishes as Nemi ponders the dangers of having too much or no faith, and of growing-up. The melancholic tone and philosophical reflections on this second page stand in contrast to the cover of the Christmas album and the opening page of the short story, which build on clichés of the drunk woman partying hard and waking up in panic in an unknown place. For the rest of the story, Myhre masters the balance between the philosophical and the mundane, magic and reality as she cleverly unpacks Cyan and Nemi’s fylleangst in a random bar somewhere in Berlin on 23 December.

Both Nemi and Cyan are overwhelmed by fylleangst, which Nemi describes as a ‘cheap feeling’ and Cyan as ‘[a] nightmare from hell’ (Myhre 2005: 5). ‘Do you want to talk about it?’ asks Nemi as both she and Cyan sit on high stools with their backs leaning against the bar counter, where two beers and two whiskeys are placed. ‘No,’ replies Cyan, holding her hands in her lap, staring down with heavy eyelids covering half her eyes. A moment of silence follows, represented by a panel with no text showing the two women sitting in the same position as in the previous one. Cyan’s facial expression is, however, changed. Her eyes and mouth are wide open in an expression that indicates fear and panic. Then, Nemi and Cyan start talking, and they do so for the rest of the story as they embark on the journey back to Oslo. All along, fylleangst follows them like a heavy, atmospheric load that is impossible to escape. Many of the following panels are heavy in text, which suggests that an important strategy for Nemi and Cyan to deal with fylleangst is to talk through it. Unlike the verbal therapy at Dr. Fraud’s office, Nemi engages in long discussions with her friend. The conversation swirls around relationships, dating and marriage, but Myhre uses these topics, traditionally thought of as feminine in nature, to disrupt rather than reinforce female stereotypes. I argue that the gothic plays an important role in achieving that disruption.

The gothic is a very lucrative, dynamic, and mobile mode of cultural production with its own chronology, several phases, and different heights of revival throughout history, as well as specific geographic inflections (Boom 2020, Edwards and Monet 2012). Because the gothic adapts and mutates to different times and spaces, it is hard to give a conclusive definition of it. In his introduction to the Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Gothic, historian and literary scholar Clive Bloom (2020) repeatedly comes back to how the gothic combines popular and pulp appeal with seriousness when it explores themes such as otherness, social fears, physical and mental alienation, loneliness, liminality or living on the margins, to name but a few. Literary scholars Justin D. Edwards and Agnieszka S. Monnet argue that the defining feature of the gothic is its preoccupation with blurring the boundaries between the real and unreal, authentic and inauthentic, copy and counterfeit, and its resistance to gender and sexual norms (Edwards and Monnet 2012: 2-4).

While Bloom uses examples primarily from architecture, literature, and film, he also mentions how goths are influenced by the gothic tropes and ‘the tradition of gender fluidity, romanticism and masquerade inherent in the gothic art of the nineteenth century,’ although they may not necessarily take an interest in gothic literature and horror movies (Bloom 2020: 24). Goth emerged in the 1980s as a musical subgenre of post-punk, a counter-culture music scene that came to be associated with radical politics and a distinct style and sound: ‘black clothes; black hair; black merchandise; amphetamines; drum machines and big bass lines; dry ice; jangly guitars; minor chords and deep mournful voices, deep meaningful lyrics’ (Spracklen & Spracklen 2018: 186). In the 1990s, various subgenres of metal started to take on the fashions and claims of goth as an effective way to underscore transgression and alternativity (Spracklen & Spracklen 2018: 186). By the 2000s, goth was increasingly commodified and became mainstream, a trope of popular culture and a fashion choice (Edwards & Monnet 2012, Spracklen & Spracken 2018). Sociologist Karl Spracklen and his wife Beberly, both associated with the goth scene since the 1980s, deplore this development (2019: 188-9). Instead, Edwards and Monnet are more interested in flashing out how the mainstream goth or what they call “Pop Goth” builds on the legacies of the gothic not only to sell out, but also to transgress and resist gender and sexual norms (Edwards & Monnet 2012: 16).

The symbiosis between the gothic, goth, metal, and ‘Pop Goth’ plays out in interesting ways in Nemi. On several occasions, Myhre talks about her fascination for gothic aesthetics, but she also explains how she specifically did not want to lock Nemi in the goth subcultures of the 1990s and 2000s despite Nemi’s great love for black clothes and metal music (Myhre 2004: 145, Brandvold 2005): ‘[m]y attraction to the underground has been based on the fact that you can be yourself, but in time, it can change to the opposite. The style ends up being a uniform’ (Brandvold 2005). If Nemi dresses goth throughout the series, her alternativity is sustained not so much through her fashion style and music taste, as through her behaviour and mindset. The way in which Nemi talks through and deals with her fylleangst in ‘Half Past One, and Still Princess’ is suggestive of how Nemi resists and transgresses gender and sexual norms.

As Nemi and Cyan engage in long discussions about relationships, dating and marriage, it also becomes clear that Nemi does not believe in either marriage or monogamy (Myhre 2005: 6, 8). Cyan is consumed by her inability to trust new partners after going through a bad break-up. Nemi’s fylleangst is instead coupled with the fear of growing up and becoming cynical and faithless. In the story, Nemi’s faith—and loss thereof—are represented through the goblin Mornon, as well as a ring, which Nemi loses in Norway before ending up in Berlin (Myhre 2005: 6). It takes a perilous road trip back to Oslo before Nemi can regain possession of her ring and restore her faith. Along the way, Myhre mobilises gothic and horror tropes to destabilise the myth of the distressed, inebriated woman under the threat of sexual violence.

In Berlin, Vlad (Dracula) joins Nemi and Cyan at the bar, where he eavesdrops on their conversation and delivers occasional lines in German, but the two women are too absorbed into their own discussion to even notice him. When Nemi and Cyan rush out of the bar to catch a ride back to Norway with a truck from Toten Transport—which they spot from the bar—Dracula is seemingly awed by their guts. Toten, which is a small place in Norway, means ‘dead’ in German, but this Dracula is not up for a ride to hell, so he chickens out and stays behind in Berlin (Myhre 2005:7).

Nemi and Cyan’s journey across Germany with Toten Transport is uncanny. The truck driver, a bald man with black, unruly hair on the sides, warns Nemi and Cyan that they should not hike alone at this time of the year. ‘Hey, you wanna see something really, really scary?’ he says in English, a famous line from the prologue of the horror film Twilight Zone: The Movie (Dante, Landis, Miller, 1983), which Nemi immediately recognises (Myhre 2005: 8). Then, the driver lifts the curtain behind the chairs and shows Nemi and Cyan a mass of bloody pig heads loaded in this truck. ‘I hope none of you are hangover,’ he says, as Nemi and Cyan start to throw up. In the next panel, the women have safely arrived in Copenhagen and get ready to catch the ferry back to Oslo. ‘Wow. What an incredibly creepy guy,’ says Cyan. ‘I liked him a bit. He helped us after all,’ confesses Nemi (Myhre 2005: 9).

Myhre uses classic gothic figures such as Dracula and the creepy driver to deliver a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the public discourse on female drunkenness which demonises the female drunk (Ravndal 2008) and blames inebriated women for being sexually abused. Irony and magic have a long tradition in the literary gothic (Bloom 2020: 5, 11). In ‘Half Past One, and Still Princess,’ Myhre uses irony to neutralise the male monsters in the story, for neither Dracula nor the creepy driver are of any real threat to Nemi and Cyan despite the gruesome iconography sustained by both figures. Nemi and Cyan arrive back in Oslo unharmed, but still under the grip of fylleangst.

A magic intervention is needed to restore Nemi’s lost faith and dissolve her fyllangst. As Nemi and Cyan walk through a snow-covered park in Oslo, a raven—another gothic trope—drops Nemi’s lost ring from its beak. The last page of the story is a splash panel that shows the goblin Mornon, restored to its original red colour, peeping from behind a snow-covered fir tree, while Nemi and Cyan walk away. Against the dark-blue, starry sky, Myhre writes a message to the reader in white letters: ‘Dear reader, the only real event in this story is the most unlikely: the bird and the ring. The world is a magic place! Merry Christmas!’ (Myhre 2005: 12). The boundaries between the real and unreal are thus blurred, and Nemi’s fear of growing up and ceasing to believe in goblins and magic is for now put aside.

The coupling of fylleangst with the fear of growing up is an enduring element in Nemi, even after Nemi embarks upon a stable relationship with Grimm (see Myhre 2016: 102). Nemi’s fylleangst is never tied to breaching moral norms of female behaviour, though Grimm can be amused by the domestic disclosures Nemi makes while very drunk. In a one-page comic published in Nemi book 12, Grimm and Nemi are in their living room, both dressed in black and with long, wavy dyed black hair falling on their shoulders (Myhre 2016: 103). With a smile on his face, Grimm sits on the couch and helps himself to a muffin from a plate on the coffee table in front of him. He asks Nemi whether she remembers how she shared her secrets the night before when they came back from the city and she drank the rest of the wine all alone: that she fakes cross-stich with a pen, buys muffins from the bakery and spoils them with salt so that they appear home-made, glues her dress with superglue and staples the edges of the curtains. In line with Grimm’s disclosures, Nemi’s facial expression changes from being content to surprised and finally angry. ‘It is probably nothing to flag to Team Housewife, but I would have made a big hit with McGyver,’ replies Nemi with a grin as she moves the tray of muffins away from Grimm (Myhre 2016: 103). Here, Nemi does not contest feminine domesticity, but her creative and unconventional solutions to chores traditionally associated with women, as well as her shamelessness following her disclosure, argue for changing perceptions of womanhood.

Conclusion

Lise Myhre’s Nemi comics display contradictions in the ways in which she depicts Nemi’s relationship with alcohol. In the short stories discussed above, Nemi’s love for chocolate, or Nemi and Cyan’s interminable conversations around relationships and dating, bolster female stereotypes. On the other hand, Myhre depicts Nemi in situations that disrupt conventional understandings of the drinking and drunk woman. None of the five myths that Ravndal (2008) describes in her research apply to Nemi. She is neither Mona Lisa nor Madonna, neither sinful nor destroyed, and neither is she a successful professional woman who uses alcohol to decompress.

As to the social functions of alcohol: it provides arenas for female bonding between Nemi and Cyan, but it does not work as a social icebreaker. At the bar in Berlin, Nemi and Cyan are deeply absorbed into themselves and their conversation. When they pay attention to others around, it is an unfortunate distraction rather than a welcome opportunity to meet other people. Heavy drinking triggers their fylleangst as an ambient, morally vague, non-cathartic, and intentionally weak emotion. In fylleangst, Nemi and Cyan are troubled by the dysfunctionality, unfairness, and cynicism of the world rather than by the fear of having failed the moral norms of female conduct while inebriated. Fylleangst aside, the consequences of heavy drinking are not connected to higher risks of liver damage or cancer, while fighting and quarrelling are also what Nemi does when not inebriated. Unwanted sexual attention is successfully deflected, for the male monsters are frauds (Dr. Fraud, Dracula) and less dangerous than appearances may suggest (the creepy, but helpful driver). If Nemi has a hard time keeping a job, her alcohol consumption is not presented as a reason, as much as dull tasks, human stupidity, or the simple fact that the job does not fit Nemi’s personality and routines.

After getting together with Grimm, Nemi continues drinking, meaning that love has not tamed her into a docile partner, although she pretends to be baking and sewing. If anything, Myhre seems to suggest that (heavy) drinking is something that Nemi and Cyan just do. Nemi may not be a ‘typical girl,’ to use a phrase deployed by Kirtley in the analysis of popular, female-created American comics, but Myhre argues that drinking—and heavy drinking—are just as typical and normal for young women as they are for men. Her feminist agenda is, then, not to draw attention to the negative effects of alcohol abuse on women, but rather to normalise young women’s contested relationships with alcohol, which in Norway has been the subject of much public feedback and ambivalent attitudes.

Notes

[1] I follow Karl Spracklen and Beverly Spracklen and choose not to capitalise ‘goth’ in order to underline that the term is here used a descriptor of a music genre, a look, a style and a scene, rather than a proper noun, which is used to describe a nomadic Germanic people (the Goths). Spracklen, Karl & Beverly Spracklen. The Evolution of Goth Culture: The Origins and Deeds of the New Goths (2018), Bingley, UK : Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 3.

[2] Despite its success, there is surprisingly little scholarship on Nemi in Norway. Two master theses put gender at the core of their analysis when they compare Nemi with Pondus (Øverli, 1995-), which to date tops the list of most sold Norwegian comic strips. Odddrun P. Løkken, «’Jeg har et halvt hjerte på to steder—og sitter hjemløs i midten.’ Samliv og samlivsbrot i Pondus og Nemi», University of Oslo, 2013 and Martin P. Wollert-Nielsen, «’Jeg skjønner meg ikke på damer, jeg’: en undersøkelse av hvordan mannlige og kvinnelige aktører skaper mening i tegneseriene Nemi og Pondus», University of South-Eastern Norway, 2016.

[3] This and all following translations from the Norwegian media and the Nemi comics are mine.

[4] Espe mentions four comic strips created by women cartoonists: Nemi by Lise Myhre, the Swedish comic strips Zelda by Lina Neidestam and Lilla Berlin by Ellen Ekman, as well as Ting jeg gjorde by Danish-Norwegian-Sami Maren Uthaug. In my research, I have contacted the National Library of Norway and the Norwegian comics organization Norske Tegneserieforum (NTF) to get more precise statistics, but neither organization keeps specific records based on the gender of the comics artists.

[5] One of Godø’s anonymised informants describes fylleangst as ‘an even cheaper relative of shame’ (Godø 2008: 21).

[6] According to El Refaie, a verbo-pictorial metaphor in comics is ‘[t]he combination of a picture of a concrete element and a verbal message that together create metaphorical meaning’ (El Refaie 2019: 116).

REFERENCES

Birkeland, Tone, Gunvor Risa & Karin Beate Vold (2018), ‘Teikneseriar,’ in Norsk barnelitteraturhistorie, 3rd Edition, Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget, pp. 366-378.

Bitsch, Anne (2012), Bak lukkede dører. En bok om voldtekt, Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

Bloom, Clive (2020), ‘Introduction to the Gothic Handbook Series: Welcome to Hell,’ in The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Gothic, pp. 1-28, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-33136-8_1 (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Brandvold, Åse (2005), ‘Neminismen er her,’ Klassekampen, 19 December 2005, https://arkiv.klassekampen.no/32581/article/item/null/neminismen-er-her (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Edwards, Justin D. & Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet (2012), ‘Introduction. From Goth/ic to Pop Goth,’ in Justin D. Edwards & Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet (eds.), The Gothic in Contemporary Literature and Popular Culture: Pop Goth, New York: Routledge, pp. 1-18.

Eik, Espen (2004), ‘Rollemodell for slemme piker,’ Aftenposten, 8 October 2004 (retrieved from Atekst 4 March 2022).

El Refaie, Elisabeth (2019), ‘A Tripartite Taxonomy of Visual Metaphor in Graphic Illness Narratives,’ in Visual Metaphor and Embodiment in Graphic Illness Narratives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 81-117.

Eon (1998-), created by Lars Lauvik.

Espe, Lasse (2018), ‘Hvorfor publiserer ikke de største avisene dagsstriper tegnet av kvinner?,’ Aftenposten, 13 May 2018. https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kronikk/i/qnMRxE/hvorfor-publiserer-ikke-de-stoerste-avisene-dagsstriper-tegnet-av-kvinner-lasse-espe (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Fjær, Eivind Grip (2015), ‘Moral Emotions the Day After Drinking,’ Contemporary Drug Problems, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 299-313.

Frangos, Mike C. (2020), ‘Liv Strömquist’s Fruit of Knowledge and the Gender of Comics,’ European Comic Art, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 45–69.

Gisle, Jon & Øyvind Holen (2021), ‘Nemi,’ Store norske leksikon, 18 September 2021, https://snl.no/Nemi (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Godø, Marian (2008), ‘En ekskursjon i fylleangst,’ in Skamløse damer og kunsten å blåse i det som ikke gjør noe,. Oslo: Kagge Forlag, pp. 9-20.

Huntebrinker, Berit (2020), ‘Narrating environmental citisenship: social responsibility in Lise Myhre’s Nemi,’ paper presented at the 2020 International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference, 29 June 2020, https://figshare.arts.ac.uk/articles/presentation/Berit_Huntebrinker_-_Narrating_environmental_citisenship_social_responsibility_in_Lise_Myhre_s_Nemi/12580445 (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Holen. Øyvind (2021), ‘Lise Myhre,’ Store norske leksikon, 18 September 2021, https://snl.no/Lise_Myhre (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Ishii-Kuntz, Masako, Guro K. Kristensen & Priscilla Ringrose (2022), ‘Introduction: Comparative Perspective on Gender Equality in Japan and Norway,’ in Masako Ishii-Kuntz, Guri K. Kristensen & Priscilla Ringrose (eds.), Comparative Perspective on Gender Equality in Japan and Norway. Same but Different?, New York: Routledge, pp. 1-12.

Kirtley, Susan E. (2021), ‘Introduction. The Women’s Liberation Movement in Comic Strips,’ in Typical Girls. The Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips, Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, pp. 1-31.

Kitterød, Ragni H. & Mari Teigen (2021), Feminisme og holdninger til likestilling – tendenser til polarisering?, Oslo: Institutt for samfunnsforskning. https://samfunnsforskning.brage.unit.no/samfunnsforskning-xmlui/handle/11250/2756827 (accessed 13 November 2022).

Lilla Berlin (2013-), created by Ellen Ekman.

Løkken, Odddrun P. (2013), «Jeg har et halvt hjerte på to steder – og sitter hjemløs i midten”. Samliv og samlivsbrot i Pondus og Nemi, Master thesis, University of Oslo.

Myhre, Lise (2004), Nemi: Enhjørninger og avsagde hagler, Oslo: Egmont serieforladg.

Myhre, Lise (2005), Nemi julealbum, Oslo: Egmont serieforlaget.

Myhre, Lise (2012), Nemi: Princess of darkness, Oslo: Egmont serieforladg.

Myhre, Lise (2016), Nemi: Med Grimm og gru, Oslo: Egmont serieforlag.

Ngai, Sianne (2005), ‘Introduction,’ in Ugly Feelings, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 1-37.

Pang, Xueqi (2020), ‘Kritiserer norske tegneserier: – Fantasiløsheten plager meg,’ VG, 21 December 2020, https://www.vg.no/rampelys/i/eKzxgQ/kritiserer-norske-tegneserier-fantasiloesheten-plager-meg (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Pondus (1995-), created by Frode Øverli.

Radio Gaga (2001-), created by Øyvind Sagåsen.

Ravndal, Edle (2008), ‘Kvinner og alkohol,’ in Fanny Duckert, Kari Lossius, Edle Ravndal & Bente Sandvik (eds.), Kvinner og alkohol, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, pp. 37-66.

Reisto, Matti (2004), ‘Lar Nemi bli på bar,’ Adresseavisen, 6 October, 2004, (retrieved from Atekst 4 March 2022).

Rocky (1998-2018), created by Martin Kellerman.

Romu, Leena (2022), ‘Smashing the Ideals of Docile Femininity. Humoristic Strategies of Feminist Resistance in Finnish Comics Magazines of the 1990s and 2000,’ European Comic Art, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 7-25.

Sätre, Trond (2019), ‘Ny giv for norske striper,’ Serienett, 2 March 2019. https://serienett.no/serienett/tegneserier-i-norske-aviser/ (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Spracklen, Karl & Beverly Spracklen (2018), The Evolution of Goth Culture: The Origins and Deeds of the New Goths, Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Stave, Tyra K. (2021), ‘Større enighet om likestilling i Norge,’ Kilden. 25 June 2021, https://kjonnsforskning.no/nb/2021/06/storre-enighet-om-likestilling-i-norge (accessed 13 November 2022).

Sørensen, Sigmund (2002, ‘PORTRETTET Kaptein Nemi,’ Dagbladet. 27 July 2002, (retrieved from Atekst 4 March 2022).

Ting jeg gjorde (2013-), created by Maren Uthaug.

Thoresen, Siri & Ole Kristian Heimdal (2014), Vold og voldtekt i Norge. En nasjonal forekomststudie av vold i livsløpsperspektiv, Report no. 1/2014. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress. https://www.nkvts.no/content/uploads/2015/11/vold_og_voldtekt_i_norge.pdf (last accessed 13 November 2022).

Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), dir. Joe Dante, Johh Landis & George Miller.

Vedøy, Tord Finne & Astrid Skretting (2009), Bruk av alkohol blant kvinner. Data fra ulike surveyundersøkelser, SIRUS-Report No. 4, 2009, Oslo: Statens institutt for rusmiddelforskning.

United Nations Human Development (n.d.), ‘Gender Inequality Index (GII),’ https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index?utm_source=EN&utm_medium=GSR&utm_content=US_UNDP_PaidSearch_Brand_English&utm_campaign=CENTRAL&c_src=CENTRAL&c_src2=GSR&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxMn_1ZSr-wIV0BV7Ch1MNgIaEAAYAiAAEgIYFfD_BwE#/indicies/GII (accessed 14 November 2022).

Wehus, Walter (2017), ‘- Avisene svikter kvinnene,’ Empirix, 3 October 2017. https://www.empirix.no/avisene-svikter-kvinnene/ (last accessed 4 June 2022).

Wollert-Nielsen, Martin P. (2016), “Jeg skjønner meg ikke på damer, jeg”: en undersøkelse av hvordan mannlige og kvinnelige aktører skaper mening i tegneseriene Nemi og Pondus, Master thesis, University of South-Eastern Norway.

World Economic Forum (2022), Global Gender Gap Report 2022, https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022/ (accessed 14 November 2022).

Zelda (2007-), created by Lina Neidenstam.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey