Women with Erections

by: Amy McCauley , April 19, 2018

by: Amy McCauley , April 19, 2018

[Penis]

1. The erect penis is [for the most part] absent from the visual vocabulary of the art world & so-called ‘mainstream culture.’ The erect penis is obscene in the Greek sense of ‘hidden from sight’, or “that which is against or off the stage.” [1]

2. This optical castration seems odd, as though the vertical penis is the last untouchable thing; the final, inviolable taboo.

3. Tom Lubbock says: “Western painting, for all the intensity it brings to the human body, hardly ever does sex. It does rape. It does violence. It does solitary nakedness. But two people having normal, mutual sex? Art leaves that to pornography.” [2]

3.1 To whom does the erect penis pose danger? For whose benefit is it expelled? & if erections are excluded to protect the public, what is it the public must be protected from?

4. Williams says MacDonald says: “To a considerable extent […] porn films are about erections. The standard anti-porn response to this is to see the porn film phallus as a combined battering ram/totem which encapsulates the male drive for power … And yet, for me the pervasiveness of erect penises in porn has at least as much to do with simple curiosity.” [3]

5. Merleau-Ponty says: “That which looks at all things can also look at itself and recognize, in what it sees, the “other side” of its power of looking. It sees itself seeing; it touches itself touching; it is visible and sensitive for itself.” [4]

*

*

[Fillette, 1968]

1. Observe the engorged, balloon-like testicles; the way the phallus hangs just above our heads. Note the corroded veins streaming up its sides & splitting as they approach the hood. The reddish-gold rust which traces the folds on its rippled surface. It might be a relic, or an exhumed thing.

2. Now discern the manner in which the beak-like ‘lips’ are thrust aside by the surge of a figure. A little cloaked head emerges from its wrapping & is hauled up & out by the wire attached to a ceiling hook. You struggle to decide whether the figure is thrusting itself out or being vomited up.

3. Is it dead or alive? Is it getting born or being excreted? Is it waste product or act of creation? “The aura of death surrounds statues” says Mike Kelley. “The origin of sculpture is said to be in the grave; the first corpse was the first statue.”[5]

4. Look again & notice the testicles might in fact be overblown breasts; the ‘lips’ resemble the neck-line of a jacket. ‘Fillette’ is suddenly no longer a phallus – yet she is not quite a ‘little girl.’

5. Hans Bellmer says: “The image of a desirable woman […] amounts to a series of phallic projections which progress from one segment of a woman to configure her entire image, whereby the finger, the arm, the leg of the woman, could actually be the man’s genitals […] the phallus is finally the entire woman, sitting with hollow spine, with or without hat, standing erect.” [6]

6. In 1982 Robert Mapplethorpe photographs Louise Bourgeois with her ‘Fillette.’ Bourgeois holds the object with tenderness, cupping it like a prize in the crook of her arm. The breast-testicles, pumped & taut, bloom from Bourgeois’ elbow & her expression emits a shrewd, pure delight.

6.1 She is like a child who has hooked a goldfish at the fair. Only the swag is her own Fillette, her ‘little girl.’

7. The artist’s jacket is apparently made wholly of pubic fur, a fact which lends ‘Fillette’ the authority of a growth, an organism. The way the torso- phallus is slung so casually under Bourgeois’ arm at first suggests an attitude of nonchalance. Yet she tenderly protects the head with her outstretched thumb & index finger.

8. Bourgeois gazes straight down the camera lens wearing a playful, knowing smile. At once she manages to be a mature woman & a little girl. Yet wipe that smile off Bourgeois’ face & the image collapses.

9. You ought to admit that penises [perhaps like ‘desirable women’] are stubbornly & thoroughgoingly unself-conscious; that if anything, this photograph really grasps the ‘thingness’ of the erect penis. The penis becomes utterly & comprehensively objectified. It might be a rifle, for instance, or some perfectly harmless ‘thing.’

10. To be sure, the object resembles a perfectly clean, almost surgical ‘amputation.’ Still, we can’t help thinking of the butcher’s shop.

*

*

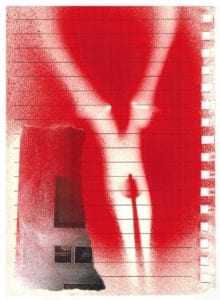

[Action Pants, 1969]

1. In a movie theatre in Munich the assembled clientele are watching pornographic films. They have paid their money & are some way into the programme. Between showings VALIE EXPORT enters the theatre wearing her custom-made ‘Action Pants’: “a sweater and pants with the crotch completely cut away.” [7]

2. EXPORT says, “I told the audience that they had come to this particular theatre to see sexual films. Now, actual genital was available, and they could do anything they wanted to.” [8]

3. There is no urgency & no desire; only a horrible sense of unstoppability about the whole scenario. The actions of undressing & performing oral have become meaningless through repetition, like the motions of shop workers acting out the motions of shop workers. Even the manoeuvring of bodies is a desperate, nostalgic gesture; the desire for a catastrophe which no amount of cash can drag to life.

4. Sontag says Feuerbach says: “our era […] prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, the representation to the reality, appearance to being.” [9]

5. EXPORT carries a machine gun. “I moved down each row slowly, facing people. I did not move in an erotic way” she says. “As I walked down each row, the gun I carried pointed at the heads of the people in the row behind. I was afraid and had no idea what the people would do.” [10]

6. In the world of pornography pleasure does not change, grow or develop. Desire must be destroyed in order to be revived in order to be destroyed in order to be revived in order to be destroyed all over again.

*

*

7. If pornography proposes an ethics of pleasure it is perfunctory. Porn walks alongside desire but never gets to its crux; it touches desire’s edge just as the viewer ‘touches’ sex by proxy. Real desire incites its own proliferation & as such, is porn’s antithesis. Rather than seek dissolution, real desire leans towards continuity, striving, diffusion.

8. EXPORT says, “As I moved from row to row, each row of people silently got up and left the theatre. Out of film context, it was a totally different way for them to connect with the particular erotic symbol.” [11]

9. Moving images carry the residual trace of an event; are brief, untouchable, bounded. Continually referring back to the original incident, cinema offers consolation via nostalgic re- performance. As Paolo Cherchi Usai says: “Be it ever so eloquent, the moving image is like a witness who is unable to describe an event without an intermediary.” [12]

10. But what if the pornographers are right. What if all desire degrades in the end?

Notes:

1. Ackerman, Alan and Puchner, Martin (eds.) (2016), ‘Modernism and Anti-Theatricality’ in Against Theatre: Creative Destructions on the Modernist Stage, London: Palgrave, pp. 1-17, p. 14

2. Lubbock, Tom (2011), Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored, London: Frances Lincoln, p. 95.

3. MacDonald, Scott, quoted by Linda Williams (1990), in Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible”, London: Pandora Press, p. 81.

4. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1969), ‘Eye and Mind’ in The Essential Writings of Merleau-Ponty, New York: Harcourt ed. Alden L. Fisher, pp. 252-286, p. 256.

5. Kelley, Mike (2003), ‘Playing with Dead Things: On the Uncanny’ in Foul Perfection: Essays and Criticism, Cambridge: MIT Press, ed. John C. Welchman, pp. 70-99, p. 87.

6. Bellmer, Hans, quoted by Gilles Néret (ed.) (1993), in Twentieth-Century Erotic Art, Koln: Taschen, p. 21.

7. EXPORT, V., elles@centrepompidou, Exhibition Catalogue (2009), p. 12

8. Ibid.

9. Feuerbach, Ludwig, quoted by Susan Sontag (2008), in ‘The Image-World’ in On Photography, London: Penguin, pp. 153-180, p. 153.

10. EXPORT, VALIE (2009), elles@ centrepompidou, Exhibition Catalogue, p. 12.

11. Ibid.

12. Cherchi Usai, Paolo (2001), The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age, London: British Film Institute, p. 31.

Photography: Amy McCauley // Artwork: Rhys Trimble.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey