Unmasking Inequality: An Arts-Based Feminist Response to a Global Pandemic

by: Miriam Kent , October 5, 2020

by: Miriam Kent , October 5, 2020

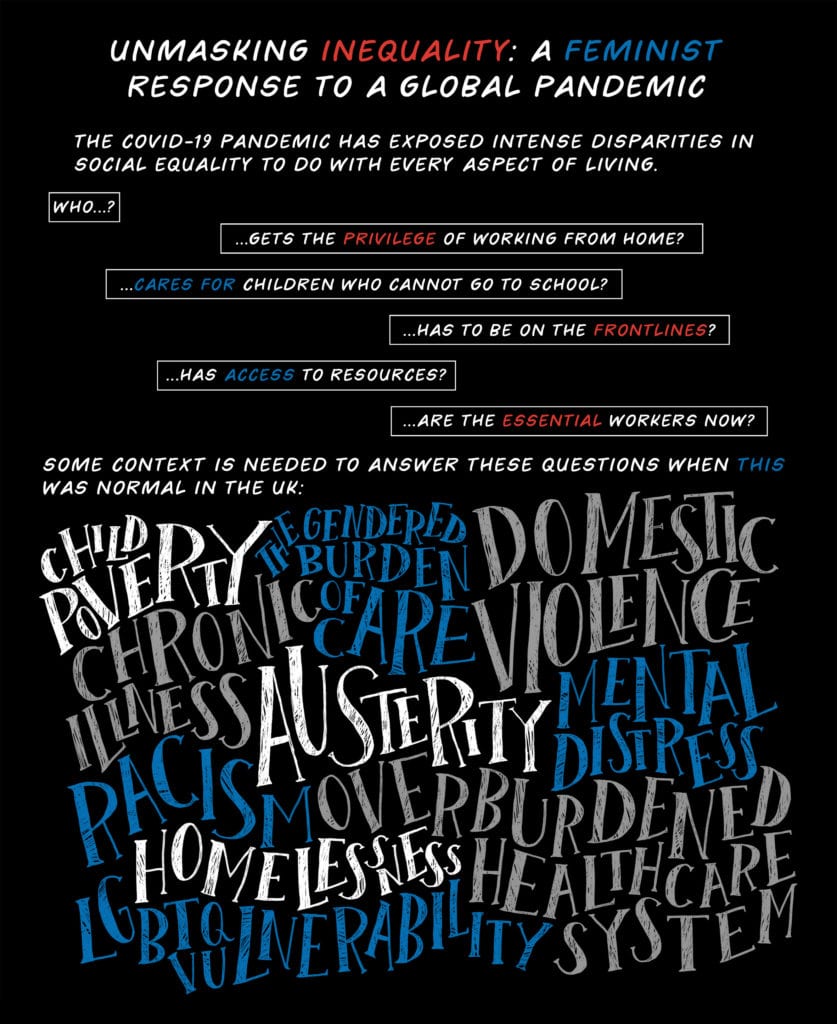

In 2020, a global pandemic disrupted ordinary life for people around the world—though it is important to note that ‘ordinary,’ does not mean ‘equal.’ Survival became more difficult for many people, not because COVID-19 was some all-encompassing villain, but because every aspect of the pandemic aggravated existing social inequalities—from the identification of ‘essential’ workers through access to healthcare and childcare during varyingly-enforced and observed lockdowns. My fellow feminist scholars and I fundamentally oppose these inequalities, and we are interested in unpacking their media representations. Likewise, media producers at all levels can and must speak to such issues. Accordingly, this project is a feminist response to the COVID-19 pandemic that takes an arts-based form, and straddles visual art and comics. It contemplates the intersections of the pandemic and social inequalities that relate to gender, race, sexuality, and class, and expresses these through creative, critical imagery.

The existing literature on the social dimensions of pandemics reveals that the exaggeration of existing inequalities that COVID-19 has brought about is not unique. For example, during the later waves of the plague, the disease ‘took on meaning as a symbol of the divide between rich and poor. Fear of the plague and fear of the poor went hand in hand’ (McMillen 2016: 20). In the 20th century, the AIDS pandemic was inextricably linked to both colonialism in Central Africa and developments in gay liberation in the US (Honigsbaum 2019: 163-65). This, in turn, had social implications through widespread discourses about ‘gay cancer’ and at-risk groups being blamed for the disease, as well as the stigmatisation of HIV+ people that continues to this day. More recently, in 2015, Jennifer Terry noted that ‘the 2014 Ebola outbreak laid bare the reality of an unequal economy of life according to which some lives are valued over others,’ particularly in the actions of the World Health Organisation and national authorities, who treated the outbreak as urgent only after a handful of white Westerners contracted the disease (Terry 2015: 6). Meanwhile, Pamela Scully has commented on the gendered nature of Ebola as a ‘woman’s disease’ inextricably linked to the gendered division of labour in households within a particular society (Scully 2015: 5).

Retrospective representations of pandemics remain just as socially significant. As outlined by Jane Elizabeth Fisher, the 1918 influenza pandemic ‘has increasingly become a convenient literary trope available to popular culture, encouraging the perpetuation of heterosexual romance, marriage, and medical research to control influenza’ (Fisher 2012: 38). In arguing that the period of the influenza pandemic was itself ‘a tumultuous transitional period when war and peace, health and illness, masculinity and femininity were all simultaneously being negotiated,’ affecting both medical and social responses to the disease, Fisher highlights a point that is particularly salient: that COVID-19 is inextricably related to now.

The intersecting social and cultural issues brought forward by COVID-19 were immediately made clear by headlines ranging from how parents should cope with childcare to where the homeless should go, as well as questions about precisely who should have the privilege of working from home. They are especially apparent in the government’s discursive reframing (see Stevano 2020) of ‘key workers,’ often low-wage, low-status, devalued people whose work had suddenly become more obviously crucial to the day-to-day running of the UK. While the mainstream media has become adept at articulating (certain) gender issues, these are often still framed within particular conventions, notably those informed by a postfeminist culture that takes into account—even embraces—feminist goals, while still keeping them suitably contained by ‘other’ identity facets such as race, class and disability. Helen Lewis’ Atlantic piece, ‘The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism’ (Lewis 2020), for instance, largely centralises heterosexual ‘dual-earner couples’ in its discussion of caregiving labour distribution during the pandemic, with some mention of single parents and minor concern for race. The issue of whether or not it is ‘feminist’ to employ a cleaner reasserted itself in some venues of cultural commentary (Ditum 2020; Silverman 2020), presumably informed by ideas, similar to those of Lewis, that dual-earner couples, having previously had the privilege of being able to afford childcare, now found themselves at a loss for how to care for their children while working, with no attention paid to what kinds of people are in the position to buy and sell this type of ‘unskilled’ manual labour. While the concern that ‘child care and elderly care can be ‘soaked up’ by private citizens—mostly women’ (Lewis 2020) is valid and true, many issues that have affected friends and colleagues (and myself) are ones that have fallen between the cracks in mainstream media commentary. These media discourses also became problematic through language that framed the pandemic within militaristic and nationalistic ideology (the assertion that we are at war with COVID-19), the possibility of gender essentialism (white men over fifty appear to be more at risk), and a new-New Scientism (the idea that, in contrast with the hard sciences, the humanities are useless against a virus).

This project was inspired, in part, by the discussions and panels in which I remotely participated during the 2020 New England Graphic Medicine Conference, which took place in the early days of lockdown, and which had been reworked into a virtual conference that included a panel on COVID-19. Graphic Medicine is a field that arguably sits at the intersection of comics studies and medical humanities (and often spills over into activism) and, according to Briana L. Martino, places ‘emphasis on transversalising medical knowledges via the visual’ (2020), and is thus suitable as a form of feminist pedagogy.

Graphic Medicine falls firmly within the domain of arts-based research (ABR). ABR is, broadly, an interdisciplinary mode of scholarly inquiry that centralises acts of artistic creation and writing at any point in the research process. A rhizomatic and complex form of knowledge-creation (Irwin 2010: 42), it blends theory and practice through an ongoing process of asking questions. It queries boundaries between disciplines, identities and ‘habits of knowing’ (Irwin 2008: 27). Perhaps ironically, given the current focus in popular commentary on the new found opportunities for the creation of art that lockdown has offered (as a means of passing ‘free time’), ABR breaks down a common binary assumption that science is true and necessary, while art is superficial and frivolous (Eisner & Powell 131-32). Through what Springgay, Irwin and Kind refer to as ‘living inquiry’ through a practice of ‘a/r/tography,’ in which the line between artist and researcher is blurred (Springgay, Irwin & Kind 2005), ABR generally ‘provide[s] access to forms of experience that are un-securable or difficult to secure through other representational forms’ (Eisner 2006: 11). These values informed the creation of my graphic piece, while the process of its assembly enabled me to further contemplate crucial issues and what actions might be taken. Finding myself lost for words, I turned to artistic forms of expression—and, as proponents of Graphic Medicine suggest, comics is a powerful and political medium for both creator and consumer.

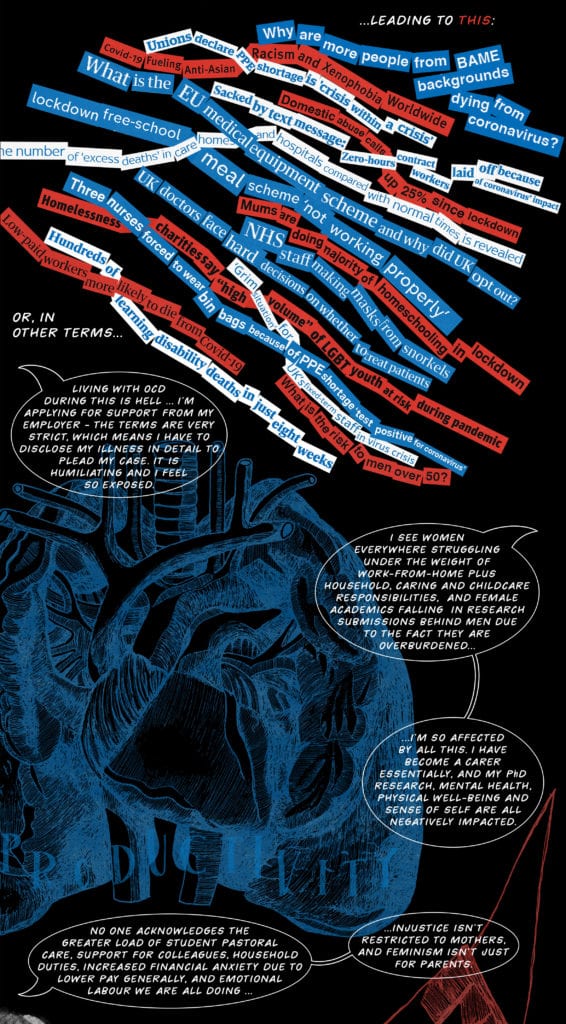

As initial studies and opinion pieces by scholars across multiple disciplines have noted, responses to the COVID-19 crisis must be intersectional: ‘It is not possible to fully understand the gender inequalities unless we examine how they intersect and articulate with other forms of class and race inequality’ (Stevano 2020). In this project, my aim has been to draw attention to these issues through a piece of practical work that also included the voices of volunteers who were willing to share their experiences with me. Graphic Medicine harnesses ‘the power of unorthodox sources, including comics, to convey meanings otherwise over-looked in conventional medical humanities scholarship’ (Squier 2015: 48), covering issues related to mental illness and disability, but also, crucially, facets of identity that inform people’s experiences of these (and, often, further marginalise them). It also has a pedagogical function, using comics as a means of expressing these issues inside and outside the classroom. For this reason, my piece is somewhat linear, with an internal narrative that outlines the situation, where it originated and what effect it has had (and what might be done in response). It was created with both pedagogical, personal and political dimensions in mind. It is sprawling and intentionally chaotic. The more I tried to incorporate panels that contained the content, the less it felt like an adequate response to the situation. Its spatial and temporal dimensions are confusing because this is a confusing time.

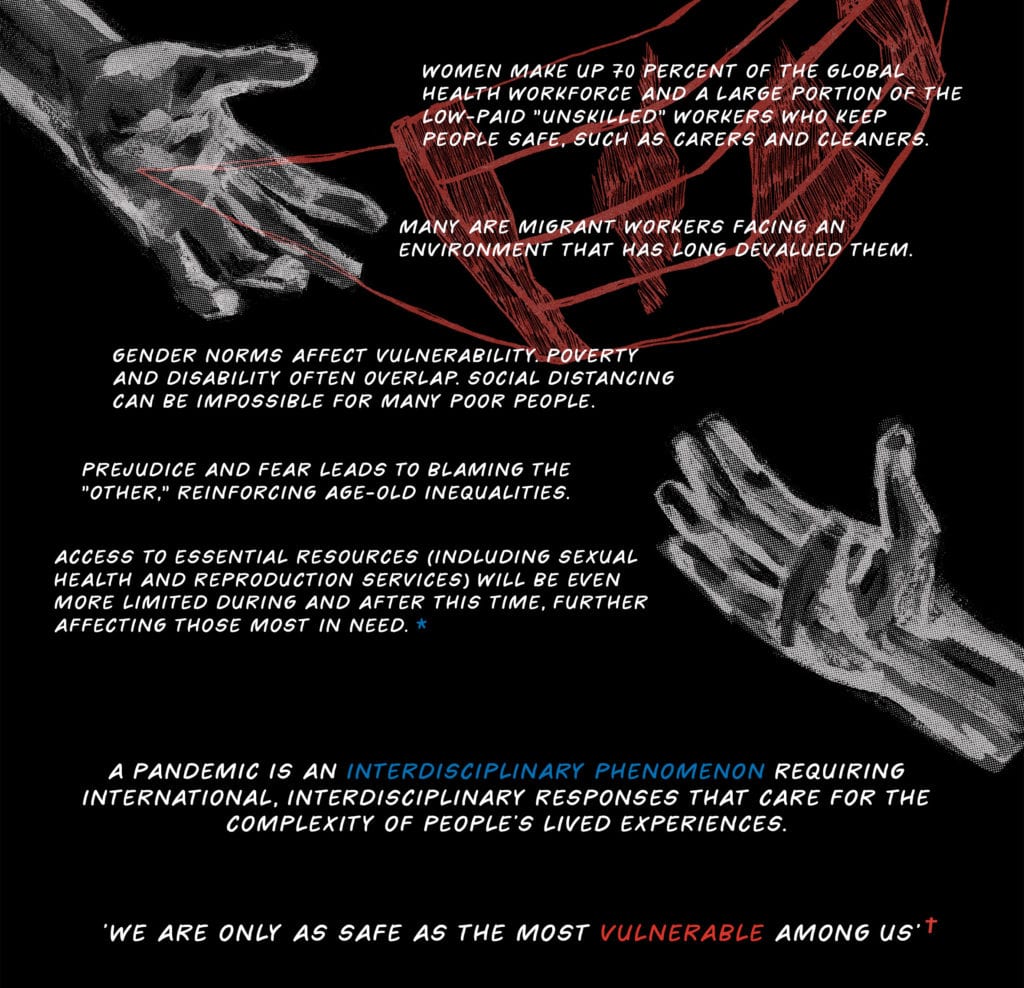

Speaking to the subject of connections and contexts, I aimed to highlight how the UK’s existing socio-economic landscape is linked to the responses, which required a kind of blanket image that merged issues of inequality while simultaneously keeping them distinct from each other. This image takes the shape of these issues hand-lettered alongside each other, struggling for space while co-existing. Finding myself in a UK context, I opted, somewhat ironically, to use the patriotic colours red, white and blue throughout the piece. This was not informed by any sense of patriotism, given the incongruity between current Conservative government policies and my political beliefs. It was instead shaped by the thematic concept of the image of lungs and a heart at the centre of the piece: lungs being the key organ affected by the disease, one that supplies the blood with oxygen, which the heart pumps around the body. In scientific illustrations, oxygenated and deoxygenated blood is represented by blue and red. This, and the metaphor of circulation as a whole, informed the arrangement of newspaper headlines that sprawl out from the hand lettering in a vein-like composition, crossing over and under each other. I chose what has become known as ‘NHS blue’ (also known as Pantone 300; see England 2000) as a key colour to stress the importance of an ostensibly socialist healthcare system at this time. The colour has become synonymous with the UK National Health Service as part of a rebranding scheme informed by New Labour policies in the early 2000s, which itself came under some scrutiny, given the contentious relationship between care and capitalism. The NHS has been dismantled by neoliberal policies that prioritise capital, and this connects with the current pandemic in the deficit of personal protective equipment and shortage of vital resources. In the interest of feminist community, I included, in speech bubbles, some quotations from participants reflecting on their own struggles during this time (these were mostly from fellow academics or early-career researchers, an imbalance I aim to address in future projects). The input from participants was collected via Google Forms, with full consent provided. I finish the piece with some initial findings from scholarly work published on the pandemic, illuminating gendered dynamics that affect how people experience it, also linking these to race, class and disability. This is accompanied by stylised paintings of hands reaching out for each other, representing the tension of social distancing, around a drawing of a facemask, an object which has become both symbol and symptom of social inequalities, both in its physical scarcity and as a means of exposing inequalities that have previously been obscured.

I am aware of my privileged position, writing and creating from a place of relative comfort and safety which has allowed me to undertake this creative research (while unemployed) in the UK, having been made redundant from my fixed-term lectureship some months ago, when the HE job market was already strained. It is imperative that marginalised frontline workers are centred in representations concerning COVID-19 in the future. The global implications of the pandemic, its media representations and the political responses it induced, should likewise not be underestimated. Feminist activists in China responded in imaginative ways to the increase in domestic violence triggered by COVID-19, highlighting the pandemic’s potential as what Hongwei Bao describes as ‘a good opportunity to experiment with flexible and creative modes of social and political activism’ (Bao 2020). In the US, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw has drawn parallels between governmental responses to the pandemic and those delivered in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Both were informed by centuries-old racial inequalities: ‘Rescues past and present illuminate in striking clarity whose vulnerability warrants robust interventions and whose does not’ (Crenshaw 2020: 11). As Crenshaw aptly puts it, ‘modern disaster relief helped turn Blackness into a pre-existing condition’ (Crenshaw 2020: 10). The situation in the US currently intersects with recent Black Lives Matter protests after the murder of George Floyd by the police, the ripples of which have been felt globally, further illuminating not only the interconnectedness of oppressions but of people standing against them. In the spirit of feminist connections, then, I end the short narrative of my graphic piece with a call for disciplines to creatively collaborate with each other, and with researchers, activists and communities.

REFERENCES

Bao, Hongwei (2020), ‘“Anti-Domestic Violence Little Vaccine”: A Wuhan-Based Feminist Activist Campaign During Covid-19’, Interface: A Journal For and About Social Movements, June 2020, pp. 1-11.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams (2020), ‘Racial Disaster Capitalism: How Modern Disaster Relief Helped Turn Blackness into a Preexisting Condition’, The New Republic, June 2020, pp. 10-12.

Ditum, Sarah (2020), ‘The Underlying Sexism of the Conversation About Cleaners and COVID’, The Spectator, 14 May 2020, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-underlying-sexism-of-the-conversation-about-cleaners-and-covid/ (last accessed 8 June 2020).

Eisner, Elliot (2006), ‘Does Arts-Based Research Have a Future? Inaugural Lecture for the First European Conference on Arts-Based Research: Belfast, Northern Ireland, June 2005’, Studies in Art Education, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 9-18.

Eisner, Elliot and Kimberly Powell (2002), ‘Special Series on Arts-based Educational Research: Art in Science?’, Curriculum Inquiry, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 131-59.

England, Paul (2000), ‘A new visual identity for the National Health Service’, Journal of Audiovisual Media in Medicine 23: 1, pp. 27-8.

Fisher, Jane Elizabeth (2012), Envisioning Disease, Gender, and War: Women’s Narratives of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Honigsbaum, Mark (2019), The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris, London: Hurst.

Irwin, Rita L. (2008), ‘A/r/tography’, in Lisa M. Given (ed), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, London: SAGE, pp. 26-29.

Irwin, Rita L. (2010), ‘A/r/tography’, in Craig Kridel (ed), Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies, London: SAGE, pp. 42-3.

Lewis, Helen (2020), ‘The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism’, The Atlantic, 19 March 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/feminism-womens-rights-coronavirus-covid19/608302/ (last accessed 8 June 2020).

Martino, Briana L. (2020), ‘Graphic Medicine as Feminist Pedagogy’, MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture, No. 5, http://maifeminism.com/graphic-medicine-as-feminist-pedagogy/ (last accessed 8 June 2020).

McMillen, Christian W. (2016) Pandemics: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Scully, Pamela (2015), ‘Combatting Ebola Requires Much More Than Science’, Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 4-6.

Silverman, Rosa (2020), ‘Does Asking Your Cleaner to Work Make You a Bad Feminist? Negotiating the Covid-19 Rule Change’, The Telegraph, 14 May 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/work/does-asking-cleaner-work-make-bad-feminist-negotiating-covid/ (last accessed 8 June 2020).

Springgay, Stephanie, Rita L. Irwin and Sylvia Wilson Kind (2005), ‘A/r/tography as Living Inquiry Through Art and Text’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 11, No. 6, pp. 897-912.

Squier, Susan Merrill (2015), ‘The Uses of Graphic Medicine for Engaged Scholarship’, in MK Czerwiec (ed), Graphic Medicine Manifesto, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 41-66.

Stevano, Sara (2020), ‘The Feminist Economics of COVID-19’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KF_jfLuQgbQ/ (last accessed 8 June 2020).

Terry, Jennifer (2015), ‘Ebola and the Unequal Economy of Life’, Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 6-12.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey