Tracing Mendieta, Mendieta’s Trace: The Silueta Series (1973-1980)

by: Hatty Nestor , June 14, 2021

by: Hatty Nestor , June 14, 2021

‘My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures, I become one with the earth’. (Mendieta 1981: 10)

Ephemeral, corporeal and fragmentary, The Silueta Series has been described as both ‘life and death-in-life as something like a mystical force’ (Esteban Muñoz 2011: 193) and a ‘deconstruction or subversion of identity.’ (Best 2007: 72) Ana Mendieta’s experimentation with the self, through absence and presence, subversion and temporality, questions the philosophical undertaking of the ‘trace’ and its relationship to performance and art. This essay conceptualises Mendieta’s Silueta Series in relation to Derrida’s notion of cinders, to question how temporality and erasure is bound to the works’ inherent performativity, as a feminist inscription into the earth. Derrida’s short book Cinders (2014)—a text centred on the very erasure of the self—is, like The Siluetas, a profound experimentation with embodiment, presence and absence. In Cinders, Derrida reckons with cinders by announcing ‘cinders are there’ (2014: iv) a phrase which re-traces itself, through repetition, as a philosophical treatise on presence and remains. The signification of presence and recognition found in Cinders is employed in this essay to unravel the feminist duration and temporality inherent to Mendieta’s Siluetas. As Susan Best commented, Mendieta’s Silueta Series signifies a ‘feminist space [of] dwelling’, where the ‘female body [is] at once present in outline and yet absent in actuality.’ (2007: 81-82) This absence and presence situates The Siluetas in conjunction with critical questions of performativity, fragmentation and repetition. Moreover, Best’s comment also generates the following question: can The Siluetas’ performativity bear witness to the exclusions of Mendieta’s name, from the past as a trace? Or, as Jose Muñoz asks, ‘[w]hat is attempted when one looks for Ana Mendieta? What does her loss signify in the here and now?’ (2011: 191)

Mendieta’s practice broadly explored the materiality and conceptualisation of traces through the body, land and time, particularly in her Silueta Series (1973-1980). Initially constructed in Iowa and Mexico, Mendieta’s Silueta (Silhouette) Series began in 1973, and created abstracted female figurations by physically inscribing her body into the land, as an expression of belonging. As Mendieta noted ‘I have no motherland, I feel a need to join with the earth.’ (1988: 76) Mendieta was re-tracing herself, partly, in relation to her exile from Cuba, and her relationship to the US. Mendieta and her sister were among many of the children within Communist Cuba who were exiled to the United States in the 1960s as a part of Project Peter Pan. Her mother joined them in Iowa three years later. Perhaps as a result of this, The Siluetas have an intimate quality, a universal, performative expression of the self-enmeshed within them. They often consisted of a variety of materials: tree branches, moss, sand, fire, and gunpowder—even on occasion animal hearts. Five years later, in 1978, The Siluetas began to reference goddesses (from Taíno and Ciboney cultures), gods, and other spiritual beings, where Mendieta carved formations into limestone grottos and mud. In 1981, she travelled to Cuba and created the Rupestrian Sculptures (1982) [Fig. 1] in Jaruco Park outside of Havana, which have slowly, but not completely, eroded over time. Over two hundred Siluetas were made between 1973-1980, and in form, location and concept they are all bound by universal omnipotence of energy and female figuration, mark-making, and perishability. [1] They all leave, as the title suggests, a Silueta of the body. They are traces of the body, a double displacement.

Much like The Siluetas, Jacques Derrida’s Cinders is a performative text, one which explores liminality, presence and absence philosophically, both in form and content. Derrida defines a cinder as a formation which ‘comes to disjoin or dis-adjust the identity to itself of the living present’ (2014: xiv) through the presence of ‘there [as a] mourning that can never achieve completion and for that reason still clings, interminably, to something still ‘there.’ (2014: 25) This location of ‘there,’ much like the outline of Mendieta’s body in The Siluetas, is precisely Cinders’ temporality as a ‘becoming-space of time’ of which life and death are only traces.’ (2014: 25) A cinder, much like ash, is the process of cross-referential tracing which ‘erases itself totally, radically, while presenting itself’ (2014: 53), as a sense of dwelling, of Mendieta’s not quite present. This presence of the body found throughout The Silueta Series is not just a dwelling, but also a self-induced mourning through nature’s elemental forces.

In response to the hegemonic, historic tradition of reducing The Siluetas simply to Mendieta’s identity as a woman exiled from Cuba to the US, the work cannot be considered solely through the prism of personal displacement, but also as an expression of the universal need for belonging. Thus, the mourning found in Mendieta’s Siluetas is considered here in line with Rebecca Schneider’s explanation of absence and performativity. As she writes, ‘loss is not an anxious flirtation, not riddled with desire, displacement or dislocation. Loss is present—literal, exigent, palpable.’ (1977: 119) Indeed, the series does more than present a linear sense of loss, instead provoking profound questions of liminality, of nationality, belonging, and feminism. Jane Blocker references the problems with reducing The Siluetas to a singular act of disappearance, when she writes:

her feelings of loss and uprooting were the sources of her series Silhouettes in progress. [Mendieta] uses her work as a means to establish a ‘sense of being’, of healing the ‘wound’ of separation. … Perceiving herself as an exile, Mendieta used her art to heal herself thus by provoking and perhaps healing others. (Blocker 2021: 77)

Therefore, throughout the Silueta Series, the incision of the body into the land generates a mark-making that is undone by the earth’s materiality and temporal transformations. When The Siluetas appear on the beach, their trace is removed by the ocean; when sculptures of the body are set on fire, they turn to ash, symbolising cremation and cinders. When a figure is made of ice, it slowly dissipates and absolves through its temporal erasure. Therefore, in The Siluetas, there seems to be a double bind (be alive, but stay dead) at play; both in the inscription of her subjectivity as a trace, and as a dwelling, a temporary inscription of the body into the land; ‘an identity anywhere.’ (Blocker 2012: 78)

***

When viewing Mendieta’s work, I encounter a dwelling that falls between absence and presence, memories folded into one another, fragments scattered across time and history. For instance, when I experience a sensation of a trace in the margins of a book on Mendieta someone has read before me— a note the reader has written to themselves—Mendieta’s trace is felt in the psyche of another, a trace I re-trace linguistically in the present. When I trace this, I am responding to what Derrida called a ‘cinder’ (remains, or ash), and these remains of traces allow me to imagine differently. Cinders are prefigured in Mendieta’s work, because the book itself is a performance of selfhood, a pursuit of giving elliptical, poetic language to the living dead. Indeed, the word ‘trace’ has a multidimensional relationship to Mendieta, both due to the metaphysical, figurative traces of life and death found within her work, and the tracing following her afterlife, linguistically and visually.

The exhibition Ana Mendieta: Traces (24 September-15 December 2013), was the first UK retrospective of Mendieta’s work solely dedicated to her art. It displayed notebooks, films, photographs, and drawings of works created by Mendieta across her twenty-seven-year career. The curator, Stephanie Rosenthal told Art in America (2013) that ‘her tragic death was always present in my mind … but it had no place within my curatorial concept.’ (Donnelly 2013) The accompanying exhibition book Traces (2013) also has an uncanny relationship with the notion of a cinder, the presence and absence of traces, and what an ethical tracing of a woman who is dead might mean for an exhibition. [2] The Silueta Series (1973-1980) particularly binds the temporal, ephemeral, and self-subject trace explicitly, where Mendieta’s body is both marked and always in a state of disappearance, self-effacement. Through the application of natural materiality—fire, water, sand, and ice, Mendieta’s figure is a presence tied to a specific time, place, and witnessing. Sediments are left, ashes dwell and move (into embers, cinders), figures are erased by lunar movements, bodies erode, diminish. The subjectivity of Mendieta, or indeed Mendieta’s subjectivity, is remade and undone, and cannot be archived, recorded, or experienced. Yet is burning the most charged form of dematerialisation?

These are complicated issues, not just of origin but also of how we witness The Siluetas in the present, as photographs of formations that were purposefully destroyed at the moment of their conception. Thus, one might also question how The Siluetas—sculptures that rely on and are constructed by the passing of time and transformation of materiality—were initially captured as photographs, static objects transfixed tangibly. In The Serial Spaces of Ana Mendieta (2007), Susan Best quotes Roland Barthes, noting that The Siluetas bind photography’s temporality to a universal sense of ‘here.’ Photography’s fixed temporality references the moment of capturing but also what cannot be seen outside the frame: as Barthes writes, ‘[photography creates] the illogical conjunction of the here and the formerly.’ (2007: 74) Thus Mendieta’s Siluetas, like the actual present, are always bound to a sense of disappearance, ungraspability, loss. In this vein, to view photographs of The Siluetas is only to experience them as a cemented moment, a fragment of the very conceptual grounds in which they were conceived. Thus their ephemerality, always dispersing and changing, becomes an object of revisitation, restlessness. Making sense of the performativity in these images is dependent upon preconceived imagery—of utilising photographs to imagine what existed outside the frame (before, after) and the linguistic descriptions of their demise. [3] Regarding the witnessing of The Siluetas, Mendieta wrote in a notebook that, ‘in galleries and museums the earth-body sculptures come to the viewers by way of photos, because the work necessarily always stays in situ. Because of this and due to the impermanence of the sculptures the photographs become a very vital part of my work.’ (Mendieta 1996: 186) Similarly, Dr. Joan Marter, claims the photographs of The Siluetas are both ‘body earthwork and photo,’ (O. Viso 2004: 70) presenting the notion that the physical Siluetas and the photographs of them are not solely documentation, but separate artworks in their own right.

Perhaps due to the different domains in which The Siluetas dwell, they are particularly ripe for re-tracing. I wonder: if the photograph is a trace of The Siluetas, how does witnessing function as an extended, trans-temporal act of tracing, or as a cinder? The Siluetas’ transient permeability remains as a two-dimensional image, albeit one which sought to possess recognition of the body. The photographs, although punctured in a temporal moment, are the only enduring archive of The Siluetas, yet are never distinguished as separate from their referent: I Mendieta, I (Derrida) the cinder. Photography is also another layer to the traces’ multidimensional quality, enticed by a temporal moment we can only witness, never enter. The images are an ambivalent pursuit of disclosure where the past, present, and future legacy of the photographs are defined in a singular there, a singular cinder. This trajectory is thus one in which the ontological is surmounted by the presence of what is captured, by the cinder (remains) in the visual framing of the figure.

Many believe Mendieta was already citing her body as an absence before her death, and the trace of her death is present in her life, in her mark-making in the land. As Blocker eloquently describes it, ‘the use of her/the body almost always approached erasure or negotiation: her ‘body’ consistently disappeared’. (2012: 33) The trace of the body is also an announcement of the self, and the absence of the body, a form of self-definition. Kaira. M Cabañas describes this as a ‘corporeal presence [which] demanded recognition with the female subject’.(1999: 14) This referring back to her work creates an uncanny temporal loop when investigating what is lost and re-found, and what remains in the present.

***

Part of The Siluetas’ enduring appeal is how they question the aestheticisation of the body and its omnipotence, which speaks to a larger reclaiming of the self; effacement, for Mendieta, was always a pursuit of earnest subjectivity. A profound expression of effacement is apparent in the untitled 1977 Silueta created in Iowa [Fig. 2]. Executed from ice, a limbless figure—unidentifiable as ‘female’— lies corpse-like in a lake. Acutely bound and constituted by the ice, the figure fails to offer the viewer plenitude or a sense of absence or presence. It is evocative, in terms of both death-in-life and life-in-death. Thus the dwelling (ethos) of the figure resides only in its material precariousness; it will perish as the ice melts. The figure’s malleability is its most compelling quality; it is inherently performative due to its changing state, despite being photographed as a static object. The amorphous state that dissolves back into the land is The Siluetas’ redeeming quality, as it both dislocates control of ever being retained as solid, and is subject to a perishing, a vanishing. In The Ethics of Earth Art (2010) Amanda Boetzkes comments that ‘[for Mendieta] the earth is not just the material of the artwork, or even its catalyst but the unfathomable presence engaged in a kind of quasi-intersubjective exchange’. (2010: 160) In this quasi-intersubjective exchange, the phenomenological, performative encounter of the figure and the earth is both dependent upon and intertwined with the substance and soil in which they are rendered. The very temporality of these works uncouple one another in their liminal temporality—both body and earth undo each other through The Silueta’s disintegration, as a universalism. Or, as Blocker comments, ‘it’s a map of Cuba made in the Iowa mud and as a result it’s neither here nor there; is a body in exile … they produce the condition, however fleeting, of the exilic.’ (2012: 82) This is not to mobilise a rhetoric where Mendieta re-performs her exile through The Silueta Series, but instead to note that the condition of their erasure (through natural forces) creates a liminal sense of exile, through their physical movement and change. They can be considered, then, as both an ephemeral expression of exile and an act of disrupting this unearthing.

Derrida’s Cinders also has a sense of movement and performative transformation, both in its subject matter and the physical experience of reading the book. For instance, when reading Derrida, I become acutely cognisant of the very real pleasures that are to be derived from apprehending language as a material textuality, from exploring the turns of critical reading, and from feeling and acknowledging the effect of traces, cinders, and time. Listen, for instance to the affective lyricism in ‘cinders are there’ there, where? and for whom?’ (Derrida 2014: 19) The tracing of a trace is perpetually indebted to what came before. The same could be claimed of The Siluetas; multiple agencies dwell, yet there is a concurrent presence and non-presence that orchestrate a material there. Repetition is bound to the very materiality of The Siluetas, as Anne Raine argues in her brilliant essay ‘Embodied geographies: subjectivity and materiality in the work of Ana Mendieta:

Obsessive repetition of Mendieta’s silhouettes both resists and points to absence and death, because the material/maternal presence they invoke is always a substitute for the imagined state of originary plenitude, and is always already lost before it can be repeated in representation. (1990: 316)

Therefore repeatability contains what has passed away and is no longer present and what is about to come, and has not yet arrived. The present is always complicated by non-presence. The trace, Derrida claims, ‘must carry the repetition within itself’ of the trace to which it responds. (2014: xi) The trace constitutes the cinder whilst rendering as other, yet ‘the cinder is exact’ Derrida writes, ‘because without a trace it precisely traces more than another, and as the other trace(s).’ (2014: 39) The cinder’s exactness and preciseness derive from its constitution being bound to a dwelling (ethos) of the living present or present non-living. It is instead a life/death relationality beyond the limits of spoken language. The cinder, following the trace, is the self-presence of the living present. The cinder— although of a similar ontological tautology as the trace—differs from the trace in that it has specific materiality, contingency, or remains; ‘a cinder is what burns in language in lieu of the gift or the promise of the secret of that ‘first’ burning, which may itself be a repetition’ Derrida writes. (2014: 9) The cinder both remains and reconfigures; it is the ember, the reminiscence of a trace.

In Cinders, Derrida’s proposition appropriately turns to the question of mourning—of how to locate the object in which to mourn—and the ambivalent temporality produced when one arrives ‘there.’ If to mourn is always predicated on a sense of responsibility, what are the demands of an absent other, of the dead? The Siluetas meditate (and produce) a sense of the lost other, provoking the viewer not to search for responsibility from within oneself, but instead to cultivate an ethicality that derives from the very recognition of Mendieta’s erased body. This introjection (absence through figurative presence) forms a singularity of ‘there’ for Derrida. The following statement demonstrates that a recognition of ‘there’ is in fact the situation for mourning (as an ethic) to derive, where a form of justice (as responsibility) might prevail:

But when you arrive ‘there’ you will not find ‘him’ or ‘them’ or even ‘it’; you will find only cinders, the traces that remain, a ‘becoming-space of time’ of which life and death are only traces. (2014: 25)

Firstly, take note of the words ‘but’ and ‘not,’ both of which reconcile with the shifting of responsibility and recognition of what one is registering as the object (Mendieta) to mourn. Yet there is something to be wary of here in Derrida’s progression from ‘him’ to ‘them’ to ‘it.’ Where one might ask, physically and subjectively is her or she? Taken as a linguistic absence, perhaps to engage with The Siluetas is not simply to register the erasure of figuration, but precisely to ask what Derrida has failed to present as a tangible object to reconcile with: her/she. Similarly, the phrase ‘becoming-space of time’ (2014: 25) is the recognition that a loss has taken place, that there is the demise of life and death, but also where something else dwells. Therefore Derrida’s ‘there’ is an elegy not simply for ‘remembering,’ but a gendered omnipresent female force of lost mourning, which calls for political action and perhaps a re-writing of that the very figuration and arrival of ‘there.’

If applied to Mendieta, this mourning puts forward the possibility to imagine the body anew, instead of re-imposing a failure to recognise her as an exiled, and indeed marginalised, woman. Mendieta’s Siluetas do not simply remain materially as an expression of being exiled; they do something further, where absence and presence meditate on both states as fluctuating, ever-changing. Perhaps their ‘light envelopes itself in darkness even before becoming subject.’ (Derrida 2014: 26) Yet to declare The Siluetas as constituted by darkening or dampening does not account for tracing others who might be found within them. The failure to apprehend the ever-changing voice in The Siluetas undoes the veracity of performing/becoming, an ‘I’ that might be dependent upon another. As Derrida writes, ‘the words ‘another voice’ recalls not only the complex multiplicity of people, they ‘call,’ they ‘ask for’ another voice.’ (2014: 9)

***

Returning to the question of performativity in the Silueta Series, the existing photographs of their creation render the female figure as ghostlike, neither present, absent, dead nor alive, where ontology is preserved by a dwelling, an otherness (see Levinas, Altérité et transcendance, 1995). The Siluetas portray an elusive identity which cannot be grasped temporally, where Mendieta’s refiguring of the body is a letting go of preservation. Not only does Mendieta prompt the viewer to question the presence and absence of witnessing, but she also destroys the witnessing of herself to herself. Mendieta traces her past through a delayed afterwardness (Nachträglichkeit) of how The Siluetas are both created and experienced. Natural forces and elements slowly erode the sculptures and performances, which was part of Mendieta’s artistic intention. In the sand, they perished through the sea’s tide, or if set on fire, became ash. Therefore, most of The Siluetas were never uncovered, or located: they were private performances. Their elusiveness is both an unformulated experience, which clears the path for a voice that might, if even fleetingly, bear witness to what Susan Best has termed a ‘future anterior’ embodied presence of the future. She writes, ‘we can say with absolute certainty when looking at The Siluetas: [that] this one will have melted, that one will have been washed away, that one will have been eroded. In short, we know, as Mendieta puts it, that the sites are eventually reclaimed by the earth.’ (2007: 74) Thus the pursuit of recognition is overturned and replaced with a not-quite conceivable trace, a cinder of what might have been. There is no origin, no telos—only a palpable cinder remains. In Bleeding Borders: Abjection in the works of Ana Mendieta and Gina Pane (2011) Alexandra Gonzenbach discusses how within The Siluetas Mendieta questions the stability of the self through permeability. Gozenbach considers Mendieta’s physical body and the trace of it to be all and one of the same temporalities. She writes,

[in] the Silueta series, the body is essential for the creation of the silhouettes, yet once the body disappears, the work destabilizes the notion of a permanent, consumable art object. The ephemeral trace of the artist’s body achieves a ‘stable’ existence through a series of photographs. Again, this stability is tenuous, as the viewer is left with the task of decoding and interpreting the documentary fragments. (2011: 44)

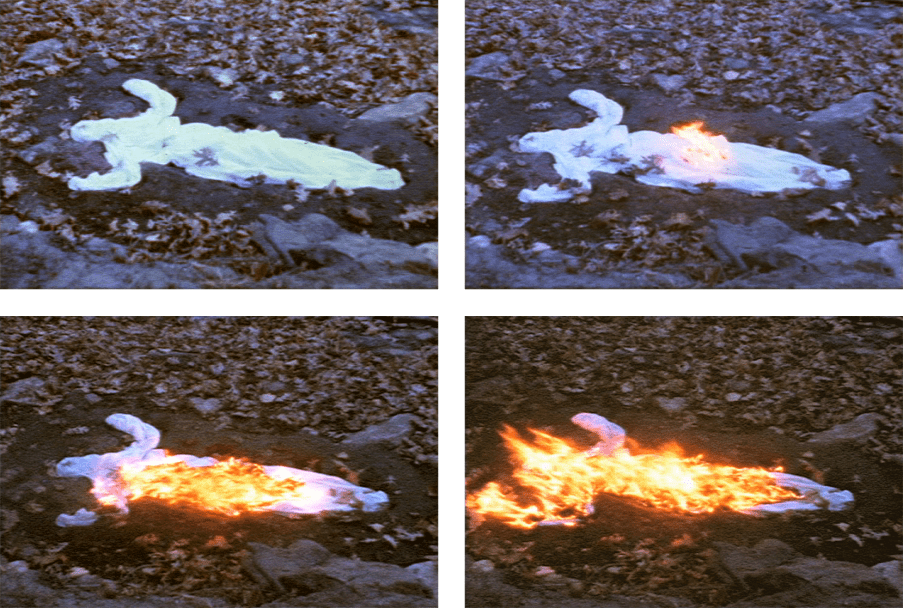

In Alma, Silueta en Fuego (Silueta de Cenizas) (1975) [Fig. 3] for instance, the living presence of the figure is subject to its own demise; it is set on fire. Amongst the quivering flames, traces are flickers of temporality, endurance. As Gonzenbach notes, the photographs of The Siluetas create a stable temporality—and indeed ontology—which is transfixed by the action of capturing and archiving. [2.5] In a similar vein, Derrida writes, with regards to what remains after the act of tracing; ‘at present, here and now, there is something material—visible but scarcely readable—that, referring only to itself, no longer makes a trace, unless it traces only by losing the trace it scarcely leaves.’ (2014: 25) Moreover, the materiality of fire is inherent to the conception of Derrida’s cinder. Fire symbolically alludes to celestial light, an aggravation or ignition. It is a transformational element, symbolic of deconstruction, where something is always left; it can be denoted that fire also creates regeneration, renewed energy. Writer Julia P. Herzberg coins Mendieta’s application of fire to that of Mexican religious imagery, when she writes that Mendieta’s ‘use of fire in tandem with the uplifted arms motif was intended to suggest the well- known subject of the soul burning in purgatory, seen in many examples including those familiar to Mendieta such as Mexican folk art and popular religious imagery.’ (Herzberg 2004: 159) Simek Shropshire also extends the question of Mendieta’s relationship to Mexican ritual and Santería practices in her essay ‘Self Inflamed’: Ephemerality and Essentialist Feminism in Ana Mendieta’s Alma, Silueta en Fuego’ (2017) when she writes that Alma, Silueta en Fuego evoked ‘ritual practices of lighting candles around graves for Day of the Dead vigils and burning paper-mâché figures of Judas on Holy Saturday.’ (2018: 5) One might question that what remains once burnt is ash, which renders Mendieta’s body as ash is also a signal to the ethnic, appropriated other (woman). As Shropshire further writes, The Siluetas and their relationship to Santería practices ‘constitutes a correlation between the individual sculpture and Mendieta’s social identities as a woman and a fetishized ethnic ‘Other.’’ (2018: 5) Therefore, Mendieta’s name and self-recognition are symbolically erased to regain agency, where fire is a compounded energy which quite literally ignites the self, a fleeting orifice of female energy; self-inflamed; a cinder.

Through burning, the destruction of the self occurs in The Siluetas. Yet I believe, just as Blocker does that ‘the disappearance of the work is a serious limitation to writing about it, yet that sense of loss is central to its meaning.’ (2012: 23) Yet fire, Derrida writes, creates the cinder. The cinder is both a consequence of the fire and a demonstration of their presence, dwelling. Its lucidity is both qua fire and predicated on an ontological différence. Consider, for instance, the transformation of fire into a cinder in the following passage:

The fire: what one cannot extinguish in this trace among others that is a cinder. Memory or oblivion, as you wish, but of the fire, trait that still relates to the burning. No doubt the fire has withdrawn, the conflagration has been subdued, but if cinder there is, it is because the fire remains in retreat. By its retreat it still feigns having abandoned the terrain. It still camouflages, it disguises itself, beneath the multiplicity, the dust, the makeup powder, the insistent pharmakon of a plural body that no longer belongs to itself—not to remain nearby itself, not to belong to itself, there is the essence of the cinder, its cinder itself. (Derrida 2014: 43)

I re-print this long section to demonstrate the complexity of fire’s elementality, and its relationship to cinders. Of note here is the attention given to Derrida’s formation of the cinder, as gaining its singular ontology after the fire. The cinder is in part the after-effect of the fire’s demise, yet its ashes, its embers, linger on as their own forms. The Silueta, like the cinder, would not be an ember without Mendieta’s body; ‘no cinder without fire [feu]’ Derrida writes. (2014: 9) The cinders différance (and the The Siluetas) is a process of recognising both loss and what remains. As Derrida eloquently writes,

the all-burning must pass into its contrary, guard itself, guard its own monument of loss, appear as what it is in its very disappearance. As soon as it appears, as soon as the fire shows itself, it remains, it keeps hold of itself, it loses itself as fire. Pure différance, different from (it)self, ceases to be what it is in order to remain what it is. (2014: 26)

Taken in relation to a sense of decay and haunting, différance, where no origin is immediately apparent, and thus cannot be comprehended by a sense of one. Instead, it alludes to what cannot be seen or heard.

***

The connection of Derrida’s cinders did not elude art historian Jane Blocker, either. In the first chapter of Where Is Ana Mendieta? called ‘Fire,’ Blocker explores the essentialist/anti-essentialist binary by deploying Derrida’s use of the cinder to reconfigure that Mendieta’s identity—which is always implicated by dislocation both physically and politically—is predicated on a loss expressed in the Silueta Series. Loss of one’s name—of rebirthing oneself in the earth—with the awareness that such formations will always disappear, is a form of incongruity, enigma. Blocker writes, ‘the paradox of essence is the paradox of identity; it is formed only through loss. There is no essence, only the search for essence; there is no identity; only the name; there is no origin, only the cinder.’ (2012: 34-35) One might conclude that to be named is a recognition that something remained, came before; a cinder. Similarly, the Butlerian notion of identity, one which marks naming as a form of accounting for the self and also a historical tension to dispute, opens on to a questioning of agency, ownership. [4] Employing Butler, as Blocker notes, means that we must work ‘against the history of names …although identity is not a matter of will or free choice, neither are we solely at its mercy’. (2012: 41) [5]

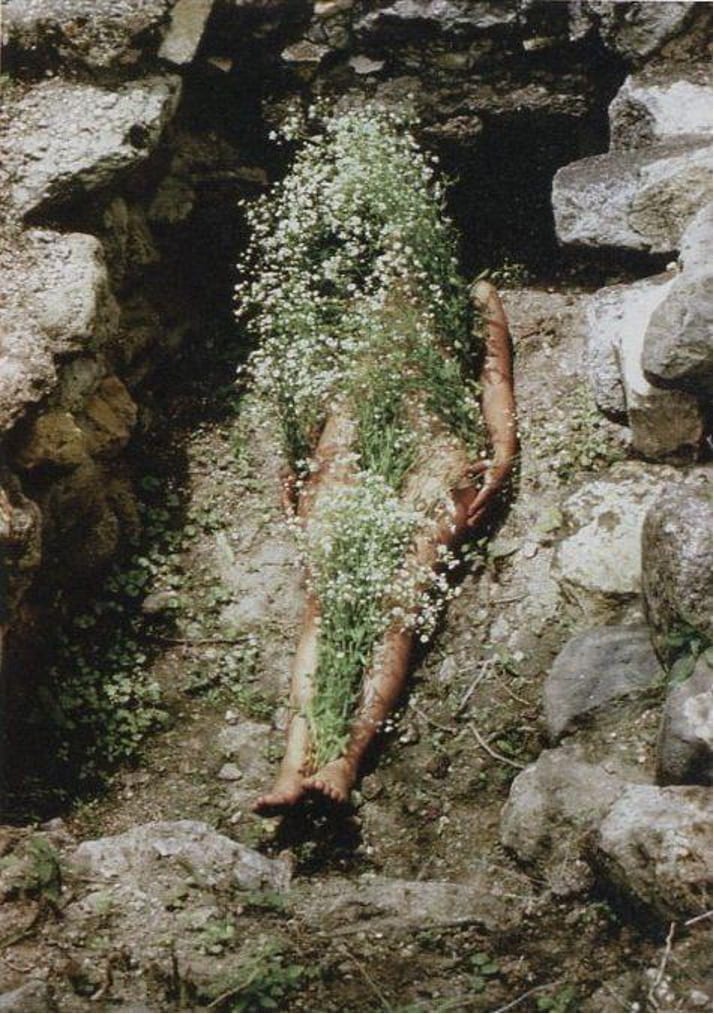

The very first Silueta, Imagen de Yagul (1973) [Fig. 4] was composed by Mendieta in Yagul, Mexico. Mendieta lay naked in a Zapotec tomb with white flowers strewn over her body, obscuring her face and features. Yet, in the photograph at least, her full body is present. In contrast to The Siluetas in which her physical body is absent, Imagen de Yagul is neither a trace, nor a cinder, but Mendieta in unison with the origins of mark-making. Yet mark-making in The Siluetas—the act of inscribing oneself in the land—differs from naming as the pursuit of acknowledgment of recognition. Instead, Mendieta gives recognition to her body situated in Imagen De Yagul. Yet absence is also a state of othering, displacement articulated through the tangible materiality of Mendieta’s physical outline in the earth. The question of essentialism and universalism occurs frequently in questions of Mendieta’s metaphysical presence and application of locality. Particularly in Imagen de Yagul, time feels like a form of corporal-permeability. The earth was a canvas for Mendieta to make an incision of recognition—or societal lack of it—as a disappearance that seems to be the only intersubjective relationality ripe for her agency.

Indeed, Imagen de Yagul is invoked as a possessive action, not of the artwork itself but its inherent quality of demise through the rhythms of the land. It is not necessarily a marking but instead an un-marking, a baptism of origin. The body here could be perceived as a form of (re)birth, a body which produces a dense, indeed flourishing inflorescence. The ritualistic nature of the body in the land is a trans-corporeal act that comes after the event (Nachträglichkeit). It is deferred action, a re-emergence of origin. It encases but also mutes Mendieta’s living self through the immersion of bodily outline. As Jane Blocker writes,

To baptise the earth is to unmark it, that is, to make it disappear from the binary structures that normally mark it as feminine, primitive, or undeveloped in a pejorative sense. It is a deconstructionist move that undoes the very hierarchies by which name is organised. To be unbaptised is to reveal the name as a cinder. (2012: 35)

Of note here is Blocker’s attention to naming as an inversion of agency, and that in (un)baptising the application of one’s identity, what remains is a cinder, a dwelling. Thus to look at The Siluetas’ figuration is to encounter a gendered, indeed feminine object, at least for Blocker. She writes that Mendieta’s Siluetas ‘deals with themes of death and rebirth staged in an earthen, womb-like cavity.’ (2012: 37) Mendieta’s body in these works is not wombed, however, but instead buried, given a sense of the underworld where flowers flourish from her (supposed) corpse, much like a burial ground. The symbolism of a womb, for its materiality at least, is to be encased within a cave; to be bound by possibility, beginnings, abundance, and potentialities.

Within a Derridean notion of the trace there is not solely an undoing of presence, but also a reckoning with such processes of fragmentation and remains. The text Cinders is an enactment of the cinders’ conception, which derives from the register of the trace. [6] As Derrida writes, the cinder is ‘the best paradigm for the trace … the trail of the hunt, the fraying, the furrow in the sand, the wake in the sea, the love of the step for its imprint.’ (2014: 25) If the register of a fragment exposes a cinder, for whom does Mendieta’s Siluetas presently remain? For whom does she remain, die, and rebirth, and what does this mean for mourning, if what remains is a mere ember, cinder? Derrida’s contention of a cinder as it ‘constitutes the self-presence of living present’ (2014: 25) is read back through the trace to resituate that which presence cannot: ‘the cinder is exact,’ Derrida writes, ‘because without a trace it precisely traces more than another and as the other trace(s).’ (2014: 21) The cinder, unlike the trace, is there but not there; ‘the cinder is not here, but there is the Cinder there.’ (2014: 15) The figuration of the cinders constitution is formed through a disjunctive remaining, or better yet a dwelling with the living present formed by traces of the past. The cinder, like The Siluetas, is in and of itself performative, bound to the incineration of traces, of a temporal burning and remaining; ‘cinders remain, cinder there is, which we can translate: the cinder is not, is not what is. It remains from what is not, in order to recall at the delicate, charred bottom of itself only nonbeing or nonpresence.’ (2014: 21)

In one regard, The Siluetas, permit a reconciliation of othering, of creating the space to ethically consider how writing about Mendieta, after viewing the trace of The Siluetas through photographs, might beckon for a sense of responsibility. Yet it is not simply a matter of recognising life or death, but something which dwells in between which cannot be summoned to language. As Wolfe describes in the introduction to Cinders, Derrida encapsulates this affective sense of language’s failure to account for the cinders’ set ontology in the following passage:

Thus the cinder, like the trace but even more than the trace, unsettles the ‘like me’ and ‘life’ of the ‘living present’ because it is ‘extended to the entire field of the living … or rather to the life/ death relation, beyond the anthropological limits of ‘spoken’ language. (Derrida 2014: xiv)

Much like The Siluetas’ material formation, cinders both erase and elicit their existence, but also offer something else. They bear witness to a more fluid, in between, state of haunting, of restlessness, of unattainability. Their performativity is a freedom from fitting into a binary of life or death while also being an instability, and a refusal. As Herman Rapaport beautifully articulates in Performativity as Ek-Scription: Adonis After Derrida (2013), ‘the cinder is the trace that comes unbidden and, upon first hearing (as ‘la cendre’) carries the erasure of its place (‘là’), as if it were merely some ash falling out of the sky, free and unmotivated.’ (2013: 215) Instead, the very act of erasure generates a sense of ontology and embodiment itself. I would like to claim, then, that The Siluetas present neither an ‘empirical or ontological actuality: not toward death but toward a living-on [survive] …of which life and death would themselves be but traces.’ (Derrida 2014: xiii — xiv) The cultivation of ontology, or indeed what might create a sense of living or survival (to use Derrida’s language), opens onto a consideration not of an absence as a signifier of demise, but instead their (arguable) feminist durability. Mendieta’s Siluetas allude to a decolonised desire for belonging, of earthly survival. They beckon towards alternate modes of reliving and giving life within death. The ephemerality of The Siluetas demonstrates that such a state is an irreducible, structural condition of existence. The contention of non-presence is woven by threads of not just linear temporality (chronos), but similar theories of disfiguration. [7] To be disfigured is to lack a personalised sense of someone: their characteristics, their unique qualities, their agency. The Siluetas harbour this quality, despite the knowledge that Mendieta’s body is the origin of mark-making; they propose a wider meditation on the displacement of females in a broader sense. The ambivalence of absence and presence demonstrates that The Siluetas are ‘a figure, although no face lets itself be seen. The name ‘cinder’ figures, and because there is no cinder here, not here (nothing to touch, no color, no body, only words), but above all because these words, which through the name are supposed to name not the word but the thing.’ (Derrida 2014: 53)

When considering The Siluetas as fragments, however, they communicate quite the opposite: they demonstrate that tracing is an effacement, an erasure of presence. They are dually an attainable recognition of a universal need to be bound to the land and location, and a restlessness which haunts the viewer. Yet through the act of linguistic re-tracing what emerges is a re-orientation to Mendieta’s trace as always already a cinder. This trajectory is one Mendieta summoned in her naming, mark-making, trace making. To obtain a sense of the complexity of the word trace at work in regards to Mendieta, we must register The Siluetas as a perishable living absence which renders as a cinder (presence) to be re-traced beyond conceivable liveability. It is ‘extended to the entire field of the living’ as Derrida puts it, and moves ‘us beyond present life … its empirical or ontological actuality: not toward death but toward a living-on [surviving].’ (Derrida 2014: 25) The Silueta speaks, not vocally but aesthetically. It says ‘there are cinders there … cinders there are.’ (Derrida 2014: 5)

Mendieta’s Siluetas demonstrate that erasure and loss which materialises in land reveals a potential for a renewed way of recognising the self, or gaining agency; a dwelling (ethos) of a cinder, a fragility, ‘a ghost, a flame, ashes.’ (Derrida 2014: vii) In this spirit, Mendieta’s Siluetas are not then or now but instead a series of ghosts which sought to find a locality, a burning through ontological dislocation, a capturing of this demise. Therefore, a sense of Mendieta, as a trace in the Silueta Series and the written form, prevails as embers, cinders. Derrida attributes the delicacy of languages’ temporality (via an urn/fire) as ephemera which can be eroded and translated into sediments: ‘the urn of language is so fragile’ Derrida notes, ‘it crumbles and immediately you blow into the dust of words that are the cinder itself.’ (2014: 35) For it is the register of the cinder which is responsible for not just a proto-linguistic signifier in The Silueta Series, but also a physical mark-making that remains once the trace has been dispersed. If the cinder of Mendieta is constituted by a tracing of the cinder—and cannot be registered without such recognition—then one must see her ‘I’ as an effacement, a dwelling, an ‘I’ which yearns for an answerability. Because The Siluetas, if only conceived for their singularity, are much like cinders: strange even to themselves.

Notes

[1] It is important to note that the official date of The Siluetas conception has been widely debated. According to the director of Galerie Long Mary Sabbatino, there are thousands of more images at the Estate of Ana Mendieta archive. This also poses a complicated question as to the life/death binary of The Siluetas, and if such images should all be included under the ‘Silueta rubric’. Indeed, as Charles Mereweather argues the first Silueta was Silueta de Yemaya (1975) or Untitled (Flower Person), a piece often overlooked by the majority of critics. For further information about the historicization of The Siluetas, see Charles Merewether, ‘Ana Mendieta’ Grand Street 17 (Winter 1999) 40:50.

[2] For further reading see Julia Bryan-Wilson, Adrian Heathfield and Stephanie Rosenthal, Ana Mendieta. Traces (Ostfildern: Hatje/Cantz, 2013).

[3] The Siluetas were captured on Super-8 film and 35mm slides, the majority of which are housed at the Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, at Galerie Lelong, New York. The slides and negatives show that Mendieta captured The Siluetas at the moment of their demise and disintegration. The photographs capture a singular temporal moment, which is opposite to the conception of The Siluetas, as forms predicated on a sense of loss. Whether the photographs are artefacts that capture a momentary event of The Siluetas, or function as an extension of the artworks, is difficult to differentiate. Yet they do provide the viewer with further temporal elaboration. What is clear, however, is that Mendieta intended The Siluetas to transcend their decay, to be archived, and remembered. Photographs bear witness to the event, but do not show The Siluetas for their decay and changing state: a gesture in wanting to be remembered.

[4] The question of film in Mendieta’s work and this medium’s difference from photography is discussed in Chapter Seven.

[5] See the section ‘Against Ethical Violence’ (pp. 41-83) in Giving an account of Oneself (2005) by Judith Butler for a further exploration of accountability, morality and recognition.

[6] The role of the trace can be found in the evolution of the text Cinders, too. It was initially performed by Derrida and Carole Bouquet in 1987 for journal Éditions des femmes. They both read the text in its entirety aloud, and recorded on old fashioned tapes. The experimental performativity of the text is not just in its linguistic formality but also its conception — as a tracing of traces. Notice the [elle-là] ‘she’ in the text, which perhaps gives reference to a female voice, or trace of another. For further notes on the performance, and the role of performativity after deconstruction see, Mauro Senatore, Performatives After Deconstruction, (London, New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 197-236.

[7] For further experiments and interpretations of the word ‘threads’ and performative lyricism see ‘Metaphors of Weaving’ by Nisha Ramayya in Threads, Clinic Publishing Ltd, 3rd edition. (2018) pp. 29-46.

REFERENCES

Alvarado, Leticia (2018), Abject Performances: Aesthetic Strategies In Latino Cultural Production, Durham: Duke University Press.

Barthes, Roland (1977), ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ in Image/ Music/Text, trans. Stephen Heath, New York: Hill & Wang.

Best, Susan (2007), ‘The Serial Spaces of Ana Mendieta’, Art History, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 57-82.

Blocker, Jane (2012), Where Is Ana Mendieta? Identity Performativity And Exile, Durham: Duke University Press.

Boetzkes, Amanda (2010), The Ethics Of Earth Art, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia, Adrian Heathfield & Stephanie Rosenthal (2013), Ana Mendieta. Traces, Ostfildern: Hatje/Cantz.

Cabañas, Kaira M. (1999), ‘Ana Mendieta: ‘Pain of Cuba, Body I Am’.’ Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 12-17.

Derrida, Jacques (2014), Cinders, 2nd edition, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Derrida, Jacques (1994), Specters Of Marx, New York: Routledge.

Ryan Donnelly (2013) The Untold: Ana Mendieta, Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/the-untold-ana-mendieta-56344/ (last accessed 11 March 2021).

Gonzenbach, Alexandra (2011), ‘Bleeding Borders: Abjection in the Works of Ana Mendieta and Gina Pane’, Letras Femeninas, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 31-46.

Herzberg, Julia (2004), ‘Ana Mendieta’s Iowa Years: 1970-1980’, n Olga M. Viso (ed.). Ana Mendieta: Earth Body: Sculpture and Performance, 1972-1985, Washington, D.C.: Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, pp.136-179.

Mendieta, Ana (1998), A Retrospective, Exhibition Catalogue, New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art.

Mendieta, Ana (1979), ‘Introduction.’ In Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States. Exhibition Catalogue, New York: A.I.R. Gallery.

Mendieta, Ana (1988), quoted in Petra Barreras del Rio and John Perrault, Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective, Exhibition Catalogue, New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art.

Mendieta, Ana (1996), ‘Personal Writings’, in G. Moure (ed.), Ana Mendieta, Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, pp. 167-222.

Raine, Anne (1990), ‘Embodied Geographies: Subjectivity and Materiality in the Work of Ana Mendieta.’ In Griselda Pollock (ed.), Generations and Geographies in the V Visual Arts: Feminist Readings, New York: Routledge, pp. 228-249.

Schneider, Rebecca (1977), The Explicit Body in Performance, New York, London: Routledge.

Shropshire, Simek (2017), ”Self Inflamed’: Ephemerality And Essentialist Feminism In Ana Mendieta’s Alma, Silueta En Fuego’, Bowdoin Journal of Art, Vol. 4, pp. 2-20, https://www.academia.edu/32427689/_Self_Inflamed_Ephemerality_and_Essentialist_Feminism_in_Ana_Mendieta_s_Alma_Silueta_en_Fuego (last accessed 11 May 2021).

Senatore, Mauro (2013), Performatives After Deconstruction, London, New York: Bloomsbury.

Sontag, Susan (2005), On Photography, 3rd edition, New York: Rosetta Books.

Spero, Nancy (1992), ‘Tracing Ana Mendieta’, Artforum, Vol. 30, No. 8, pp. 75-77.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey