Three Generations

by: Amanda Hopkinson , June 12, 2022

by: Amanda Hopkinson , June 12, 2022

As a child in the 1950s, I would go twice a year to the Brompton Cemetery with my mother, Gerti, to visit her parents’ grave. We would enter on the south side, via the Fulham Road entrance. Almost immediately on our left, backed up against a brick wall, stood the grey marble gravestone, its scalloped twin tops faintly reminiscent of the lace doilies invariably placed on plates of apfelstrudl and vanillekipferln when guests came to our Hampstead home.

I was always more aware of the garden than the grave. ‘Dog roses,’ Gerti called them—apparently due to the resemblance of the hooked spines to dog canines—climbed over the headstone, entwining around a metal hoop at the top. We visited to view the roses in their early summer bloom, and to clip a bunch to take home. Then again in early winter to see them pruned, and for Gerti to have an annual argument with the groundsman over why the grass growing between the little walls that marked the edges of the double burial site had not been trimmed to her satisfaction, despite allegedly ‘exorbitant’ and ever-increasing annual charges. I don’t recall when I first considered the remains beneath the grass and the dog roses. How ironic it would be, after these repeated rituals, to learn if either grandparent were not lying under the grass.

One evening, as Gerti accompanied my self-conscious singing of Schubert’s Schöne Müllerin on the Blüthner grand piano—shipped out with a flat’s-worth of carpets and furniture from her native Vienna in 1936—I imagined a link to the gravestone. Shyly enquiring whether Schubert’s roses (‘half red and half white’ adorning the grave of the doomed lovers) were ‘my grandparents’ roses,’ she laughed aloud, then suddenly became tearful.

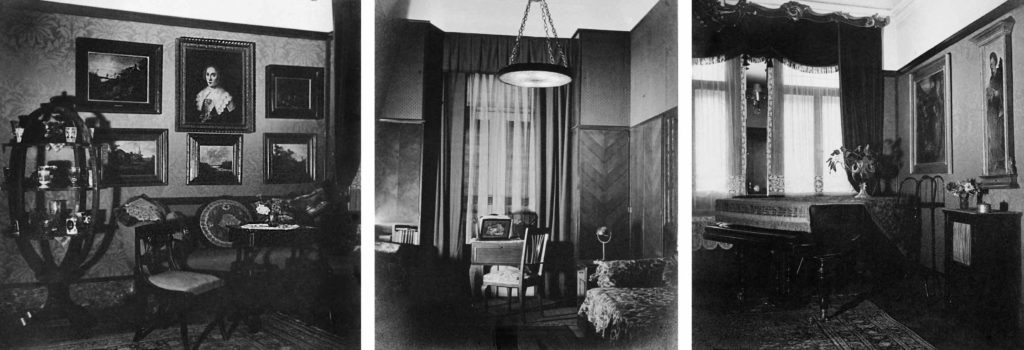

Gradually, I noticed that these grandparents whom I had never met were born long ago in another century (in Victorian times, it seemed to me, still unaware that their ‘long ago’ was under the old Austro-Hungarian empire). Victor was almost exactly twelve years Ricka’s senior, their dates of birth being 28 June 1874 and 25 June 1886. When they married in 1904, he was already 30 and she not yet quite 18. They died a decade apart, Victor predeceasing Ricka on 29 June 1938, three months after Nazi troops invaded and annexed Austria. When I was a teenager, my English father recounted a story of how Stormtroopers had entered the apartment at Gusshausstrasse, tipping the Meissen china dinner services out of upstairs windows and slashing the Bokhara rugs that my grandfather collected; of how Victor either suffered a heart attack, or a pre-existing heart condition suddenly deteriorated in consequence.

My grandfather’s given name was variably spelt either Victor or Viktor; my grandmother’s followed a bourgeois fashion for French names: Henriette. A tradition she maintained when her only child was born on 19 December 1908, naming her Gertrude Hélène. In turn, Gerti would name her own eldest daughter, born 3 January 1942, Nicolette.

‘Henriette’ puzzled me. My mother’s dressing table held a set of tortoiseshell-backed brushes, cut glass makeup boxes with silver-plated lids, silver powder compacts and a silver hand-mirror, all embossed—as the bed linen, napkins and ‘face towels’ were, at one corner —with ‘R.D.’ in modernist lettering.

‘What was the “R” for?’ I asked Gerti.

‘Ricka,’ she told me.

‘Why Ricka?’

‘It was the name of her favourite doll, and when she was a child, she wanted everyone to call her by it.’

But was she nick-named after her doll or the other way around?

There were two dolls, and Ricka was the brown-haired doll of the pair, both handmade by Käthe Kruse. She was passed through Gerti to Nicolette then on to me. The blond one was called Maia. With cloth bodies and bisque heads, they survived many moves, adorning our living rooms until the 1970s. Then burglars removed the twin dolls and the two Leicas (1928 and 1936 models), in what was clearly a targeted burglary.

I only ever once saw a Käthe Kruse doll again: in Buenos Aires in 1992. By then a writer on photography and photographers, I had gone to interview Grete Stern. I had become particularly interested in the photo-studio she and her best friend, Ellen Rosenberg, had established in Walter Peterhans’ former studio in Berlin. Called ‘Ringl und Pit’ after the women’s childhood dolls, its output combined Bauhaus clarity of light and line with modernist graphics to create a successful commercial studio. It closed once Hitler took power in 1933 and forced exile of the two Jewish photographers took Grete to Buenos Aires and Ellen to New York.

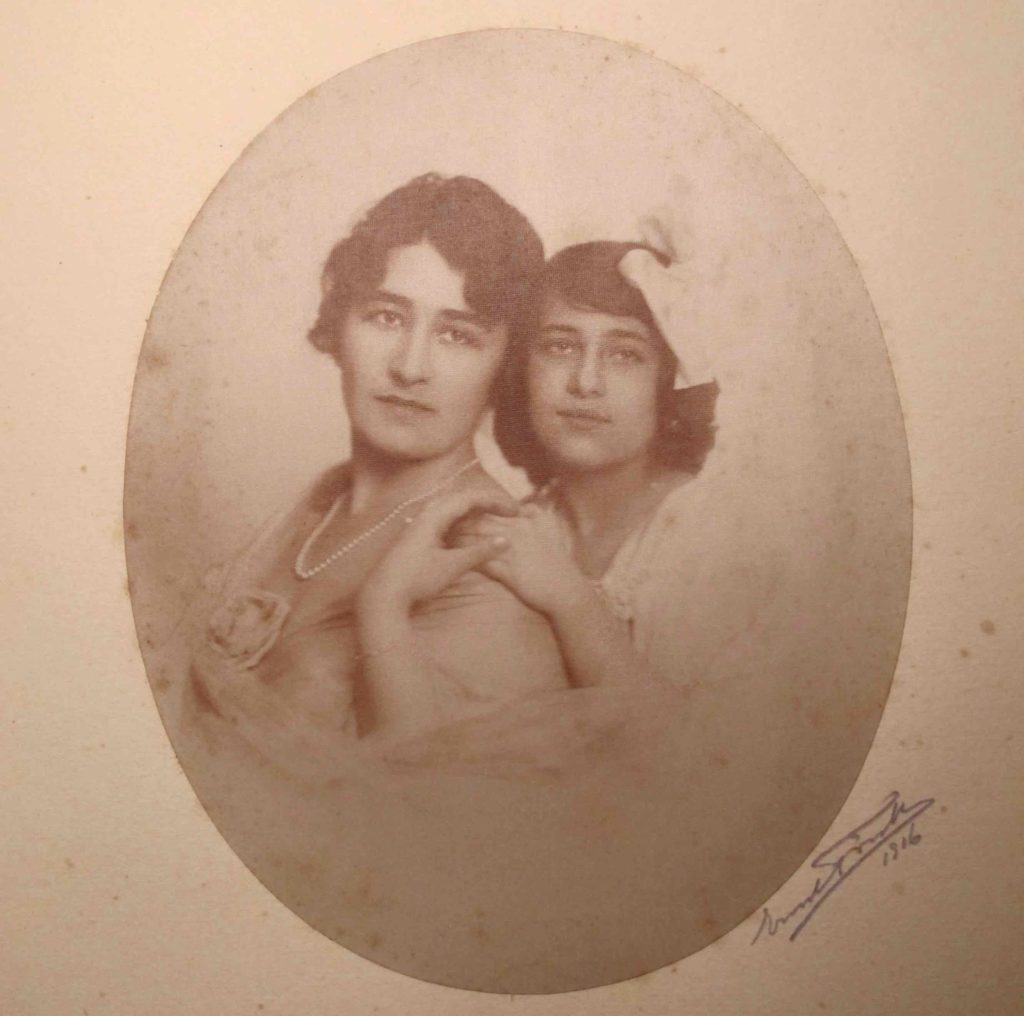

Even then, in the 1990s, I remained unaware of the importance of the camera in either Ricka or Gerti’s life. Ricka seems to have regularly visited photo-studios, always in the lavish fashions of the day, swathed in reams of luxurious taffeta and silk or wrapped in furs. She appeared to favour a three-quarter angle, head tilted slightly to look into camera. Deeply dark hair with a soft sheen and wave to it, a fine brow and almond eyes beneath wide eyebrows, a strong nose and clearly defined mouth; she was reckoned to have been ‘a beauty,’ proficient at music and dancing, gifts her daughter inherited.

Yet Gerti never forgave her mother for treating her like ‘a doll,’ brought down from her room to entertain guests, dancing a ballet suite to piano accompaniment, or to give precocious renditions of Chopin and Schumann, Beethoven and Schubert.

Ricka might intermittently have performed on the piano at the close of her regular bridge parties, but she preferred to show off the talents of her child. She was also a voracious consumer of culture, attending umpteen new theatre and opera productions (with an album of cartes de visite signed by Caruso, among others), New Year’s balls in grand hotels, and reading widely in three languages, with a particular interest in poetry, history and classical literature. My father told me that her first romantic preference had been for a cavalry captain billeted at the barracks in her home city of Olmütz (now Olomouc). It was one her family opposed, possibly on the grounds that he was not Jewish.

Gerti’s description of her parents’ marriage was ambiguous. Victor apparently came from a lower social stratum than Ricka. His place of birth was in Polish Jablunkau, annexed and rebranded Austrian Silesia two years before his birth. It was hard graft and a strong personality rather than an inheritance which helped him attain his title of ‘rope manufacturer to the [Hapsburg] Crown.’ And it was his warehouses on the waterfronts of Trieste, then still part of that empire, which stored rigging for the Austrian navy until it was disbanded in 1918. From then on Victor’s love of oriental silk carpets dominated, becoming incorporated into the residual business supplying chandlery for leisure craft.

Gerti found her father the warmer, gentler, parent. Whenever she fought with her mother, it was he who would tap on the door of her bedroom where she had retreated to sulk, with jokes and oranges to raise her spirits. In the few surviving family portraits, she poses with either parent, never with the two together except in holiday snapshots. The oval-framed picture of Gerti at her father’s knee that hangs in her bedroom is characteristic: their gaze is into camera, but their bodies are relaxed, hers leaning against his.

Yet Gerti’s father was not only the older but the physically weaker parent, suffering from a combination of lung and heart ailments, probably accentuated by his fondness for smoking both cigars and cigarettes. By June 1936, when Gerti was holding her first photographic exhibition in London [1], Ricka was occupied in accompanying her husband to consultations with top medical specialists, and to take numerous ‘cures’ in Austrian and Italian spas. For the last months of his life, until June 1938, Victor resided in an elegant former palace which once belonged to Empress Maria Theresa, situated between the Vienna Woods and the Danube, in leafy Döbling. In 1920, Baron Albert von Rothschild had converted it into a military hospital for soldiers suffering from ‘nervous ailments’ (most likely shellshock resulting from the First World War). While not specifically a Jewish hospital, the Deutsches’ acquaintance with the Rothschilds may have assisted in securing a place there.

Once her daughter had set out for London to launch her first exhibition and make her name as a photographer, Ricka adopted a routine of writing to her daily, sometimes two or three times a day. Using a dark turquoise ink, her neat handwriting covers four or more pages, and the envelope might also contain a scenic postcard or a pressed flower. Every letter opens with ‘My darling little girl’ and closes with ‘your little Mummy’ [2] sentimental diminutives that typically express affection and closeness. Whatever Gerti’s own feelings of distance from her mother and of a greater proximity to her father, Ricka herself was clearly deeply attached to her daughter. And however strong and admiring Gerti’s feelings were towards Victor, his communications with her are largely confined to adding Herzliche Küsse, Vati. [3]

Ricka keeps Gerti up to date with the gossip. In October 1936, she and Victor are back in their favourite spa hotel at San Remo, hopefully just the place for Victor’s health to improve. Between taking the waters, he gambles alongside ‘wealthy elderly dowagers’ in the Casino. ‘One is spoilt,’ according to Ricka, by the advent of films from the United States, and she ‘adores Greta Garbo.’ She also peruses Alfred Neumann’s Another Caesar (a hefty biographical novel on Napoleon III, of possible contemporary relevance). By October it is Gerti’s social engagements that occupy her: should she send her over a dirndl to wear to the costume ball at the Austrian Embassy in London, and if so which one?

Back in Vienna the Austrian press is full of news of a royal visit. As Ricka relates: ‘We Austrians are getting along famously with England since the King and Mrs. Simpson came and played a round of golf with Jews at the Lainz Country Club, before His Majesty graciously agreed to be made a Club patron.’ She continues: ‘In addition the King sought the medical opinion of Professor Neumann, and went hunting with Rothschild—the only thing he didn’t do was celebrate the Sabbath with us! As of today the government has assembled a new Cabinet —all with Jewish names have been excluded.’ She ends on a note of resistance: ‘So sad for all of us, but our Race remains incorrigible.’ [4]

By late 1936, Ricka’s letters become self-conscious, even surreptitious. She wishes Gerti to make an approach to the Austrian Consulate on her parents’ behalf: surely they have grounds to leave ‘for the sake of his [Victor’s] health.’ She requires details of Gerti’s bank account in order to cash in Victor’s pension and transfer certain large sums of money. The courier she had paid to travel to England with the funds and ‘gold bricks’ (ingots?) had given his word but has let her down. And, unfortunately, Victor’s health only deteriorates.

The woman who once led the life of a socialite was now having to assume responsibility for the declining health of her terminally ill husband, with making major life-changing decisions regarding securing a future, and with transferring all she could of their finances and possessions to her daughter, newly arrived—and as yet unsettled—in England. The once resolutely upbeat Ricka finally admits: ‘I have difficulty in not becoming downhearted.’ Survival may not be resistance but resistance in extreme circumstances can mean survival.

As Victor’s medical issues persisted, so did his spells in various nursing homes. There were repeated visits to ‘Sanatorium Edlach,’ where he took the riverine waters and received a series of ultimately fruitless treatments. By New Year’s Eve 1937, Ricka wrote again on headed notepaper quelling her anxieties and pinning her hopes on Gerti’s forthcoming visit, and plans for her wedding to Tom Hopkinson, deputy editor of Weekly Illustrated. She relays how charmed all their friends were by Tom’s visit earlier in the year to request Gerti’s hand in marriage [5], how much they enjoyed reading his collected short stories; and how Gerti’s portrait of astronomer Sir James Jeans—whose Austrian wife, organist Susi Hock, had been a fellow music student of Gerti’s—had impressed them.

On 13 March 1938, Austrians rapturously welcomed the Nazi invasion with Hitler at its head, tearing down Austrian flags to replace them with swastikas. Shops and homes were daubed with graffiti caricaturing Jewish people and slogans warning Jewish shopkeepers to ‘Go take leave in a Camp,’ alongside a gallows.

On 27 April, Ricka was issued with a Verzeichnis über das Vermögen von Juden from the Nazi administration under the direct control of Field Marshal Göring. [6] From it we learn that the family owned a tranche of building land in Insersdorf (on the eastern outskirts of Vienna) valued at RM5,000, ‘items of special value’—primarily artworks and jewellery—valued at RM4,280, solid silver dishes and cutlery worth RM600, and a quantity of shares held in hemp, jute, and mining industries, exclusive of property and liquid assets. [7]

The pressure to hasten the transfer of as many possessions and assets as she could salvage, and to prepare herself for foreign exile, coincided with emotions and decisions arising from her recent widowhood. Five weeks after Victor’s death, on 6 August 1938, Ricka wrote of how, towards his end, Victor had kept repeating ‘You and Gerti are all I have,’ a phrase which made her feel unable to transport his ashes back to Silesia, where his forbears lie buried. France ceases to be an option and she resolves to bring the ashes to England, to live either with or nearby her daughter in Lowndes Street, Belgravia, SW1.

A week before Victor died, Ricka posted another cautiously veiled letter, franked 24 June 1938. It reads:

I’m not that sure about sending things on [to you] because then I might become suspected of wishing to flee [the country] and I’d like to spare myself unnecessary upset, with only unpredictable consequences. For how long do you have permission to receive possessions from abroad as part of your immigration process? What rules does England have, with regard to furnishing or equipping a home? I’m obliged to get the whole apartment valued and report to the authorities for the purposes of ascertaining and confirming our estate and equity by 30 September. It’s a pity I didn’t follow your advice and send over all the things intended for you—the pictures, silver, porcelain, carpets and curtains, etc—in January.

On 21 September a Veränderung [8] was submitted by the lawyer appointed by Victor to deal with his estate. It effectively denounced the new widow to the Nazi authorities and was copied to the chief Police Commissioner in Berlin.

A letter sent upon Ricka’s return to Vienna (24 August 1938) refers to visiting Paris, adding she’d best withhold comment on the ‘political upheavals’ in either city. While abroad, amid constant pressure to find a way out, possibly as a means of getting beyond grief and loss, Ricka made time to pause and have certain essential items hand-stitched for her daughter’s trousseau. Somehow three have survived: a silk nightdress with matching bed-jacket in what Ricka described as ‘shrimp pink’ with an intricately embroidered nightwear-case, and a floor-length, satin dressing gown with a golden sheen.

Sadly, however, Ricka was unable to attend her daughter’s wedding at the Chelsea Registry Office on 7 October 1938, much as she longed to. She wrote directly to Tom, for, as she had explained to Gerti, she ‘so wanted to show fondness towards him, and send all my hopes for their good fortune together.’ In a separate letter, she says she ‘must be patient until my nerves have calmed down, since the smallest thing upsets me at present.’ She believes there has been a ‘misunderstanding’ with Gerti: a possible reason why she addresses her earlier note to Tom and sends the second without a named addressee.

Unable as yet to leave for England on 22 September—a project on which her heart seems more set than is her daughter’s—Ricka’s final entry in her pocket diary for 1938 is a single word: ‘Breitenstein.’ On 28 September Ricka wrote to Gerti that she had ‘taken refuge in the Breitenstein house.’ ‘Forcible Aryanisation’—in this instance expropriation—had already become the order of the day, as had increasingly brazen attacks on Jewish people by Stormtroopers and the Hitler Youth on the street, even in their homes. Breitenstein seems unlikely to have been a house the family owned (it was not listed in the Veränderung). It is unclear where in the Bavarian Mountain resort she was staying, whether in a house they rented or that of friends. However, it was where Ricka sought refuge once her home was requisitioned, and she was rendered homeless.

Her personal disaster, alongside a generalised—and increasingly violent—persecution, is presumably part of the ‘degradation’ to which Ricka is subjected in Vienna. Her late husband’s business properties, investments and bank accounts were now confiscated. [9] She therefore refers to reduced living standards, having ‘been left with nothing like the income I had anticipated.’ Matters which serve to belie the light-heartedness of her closing quip: that in order to enjoy another rubber of bridge she should come to London, where her bridge partners already anticipate her arrival.

Either way, her Breitenstein stay seems to be of short duration. On 11 October, four days after Gerti’s wedding, a strange letter reaches Chelsea. Its contents read like a hand-copied telegram, intended to double the chances of either version reaching its destination. Both address and letter are in capital letters: perhaps either Ricka’s housekeeper, Anna or Agnes, the cook, had been entrusted to take it both to the telegraph and the post offices.[10] It expresses the utmost urgency and importance to both sender and recipient:

LETTER RECEIVED

ASKING AT LAST

FULFILMENT OF MY WISH / REQUEST

DO NOT VISIT, AS IN TRAVEL PLAN, TRAIN

NO NEWS / CONTACT

NEITHER PHONE CALL NOR LETTER AS POINTLESS [11]

It is clear that Gerti should not attempt the journey to Austria, rather that Ricka is planning her own departure for London. It is unclear whether she has not heard from her daughter or is prevailing on her not to risk making contact by whatever means. Since Tom and Gerti were by then honeymooning in the Portuguese fishing village of Nazaré, Gerti had no plans to travel to Vienna.

Following this unsigned note, Ricka wrote once more to her daughter. This time, she wishes to unburden her unhappiness: there could scarcely be a sharper contrast between her daughter’s joy on starting out on a new life and her own misery at having to abandon her old one. Her handwriting is so shaky, the punctuation so generally missing, as to be illegible in parts. Her apartment has just been emptied and expropriated by the Nazi authorities, according to new laws of ‘Aryanisation.’

Yesterday afternoon, I passed through the Brahmsplatz as the furniture was being taken out and loaded up, and I stole a final glance inside the empty apartment for the last time.

‘Aunt’ [the concierge?] and S[indecipherable] were there—I saw a dog left behind, and envied him [for being] better off than I—but then, matters must unfold according to God’s will. I had overseen the apartment being built, helping out over every problem with both the architect and labourers, and now it seems that even that too was just a ‘loan,’ and counts for nothing, like everything in life. So one can only be glad to have at least enjoyed some good days and precious moments there, and for those I am indeed truly glad and grateful.

A month later, on 2 November Ricka (unusually) admits to a deep depression, possibly the reason she was seeking help from an apparently unsympathetic doctor. Ever since Victor’s death ‘nothing but the thought of joining her only child has kept her from envying her husband his “final rest”’. Her one hope is to be with Gerti and Tom in Chelsea. Her needs and expectations are modest: she does not wish to be a burden, nor to cast the least shadow on their happiness.

After this the letters abruptly stop. We know, however, that in February 1939, Ricka was issued with her formal Abmeldung, a surrender of her citizenship to the Deutsches Reich, instrumented as an essential prerequisite to departure.

Only on 28 May 2021, did it suddenly occur to me to phone Brompton Cemetery with enquiries concerning the grave. From Royal Parks supervisor Callum MacKenzie, I learned that Victor’s ashes had been interred there in January 1939, one month earlier than the Abmeldung was issued to ‘Sara’ Deutsch. [12] It established that Ricka had already fled, since she brought the urn and arranged the interment. Her journey, of which we know almost nothing, would have been the more dangerous without official permission to leave.

Much like present-day migrants across the Rio Grande, Ricka may well have been accompanied by a ‘coyote,’ to guide her around or across frontiers. This was, presumably, the mysterious Czech courier who, having accompanied her into Switzerland, vanished once they reached Paris. Ricka must therefore have reached London between November 1938 and January 1939.

We do not hear from her again until February 1940, when she sends a note to Gerti about coming ‘to town.’ Since it was postmarked Leatherhead, she was presumably staying with friends there, opening up the possibility she may have arrived by plane at London Croydon Airport.

When Nazi forces launched the Blitz in September 1940, Tom rented and moved Gerti into ‘Summer Cottage,’ a former farm labourer’s cottage in Turville Heath, Buckinghamshire. Tom took a still smaller ‘bachelor flat’ (at The Boltons, South Kensington) where he spent the working week editing Picture Post—a ‘reserved occupation’ exempting him from military service.

Tom visited the cottage at weekends, usually bringing one or both of his daughters from his previous marriage to Antonia White. It was so cramped that the girls had their own ‘shed’ down the garden, where they slept guarded by their beloved poodle Jenny, and with their donkey, Jeremy, tethered outside. Also outside, next to the cottage’s front door, was the toilet-come-shower-room, with its own paraffin heater, so apparently the warmest room.

Such accommodation was considered unsuitable for Ricka, although we don’t know if she was consulted. She was moved into a bedsit in North Oxford, clearly in a very fragile frame of mind, where she remained until 1944. According to what Tom told Lyndall as an adult, Ricka planned, and possibly made, her first suicide attempt during her time there. Unfortunately, as always, Ricka does not date her letters, although her birthday, to which she refers, was on 25 June:

Beloved daughter Gerti,

Both you and Tom have my most heartfelt thanks for your loving birthday wishes and for thinking of me also with the bonbons and the flowers! Sadly, these are no times for celebrations and so, out of fear about providing any further commentary, I’ll [semi-legible] get to the heart of the matter [that of my] final destination [semi-legible which includes the word ‘Brompton’] by your father’s side—this is where I’m asking you to inter my ashes. I hope I’m not causing you too much trouble with my final wish. Don’t be too sad, I thank you for all that has been lovely, loving and good that you have brought into my life—Tom too, who has only ever been loving and kind to me. May you bear together the burden of the difficult days to come.

In the right-hand drawer of the chest of drawers is the ‘last minute bag’—key enclosed [ie with this letter]. There you will find the small case with my brooch, earrings and watch—[and a] deposit box [?] receipt from Selfridges. Cheque book and final (or most recent) letter from the Midland Bank—receipts [for?] and inventory [of?] the items that are still with Anna [in Vienna]. Any of my clothes which you can’t make use of [may] be of some service to Heidi Auspitz if you can pass them on, maybe ask Helly if she needs anything for Huschi? Please send my old friend Herzka (?) a box of Havanna [cigars] and three bottles of Pommard [Burgundy wine]. For Helly a box of Black Magic and for Huschi twenty pounds for (indecipherable) birthdays. To Anthony, Ricka’s cousin and the sole survivor of his immediate family … £50 (45 Taylor Hill Road, Lockwood). Give my greetings also to Bertl and her family, the same for Helene Strauss (Cambridge), etc.

Farewell, my heart

your mother, for whom you must not grieve.

The envelope is unstamped, and must either have been sent by hand or, more likely, left somewhere for Gerti to find. On it, Gerti has written in red ink: ‘Farewell before first attempt’: it was evidently not the last.

The evidence as to whether Ricka, at either the second or third attempt, finally succeeded in committing suicide is ambiguous. It was never mentioned as I was growing up, and I now realise that Gerti generally avoided talking of her mother. But in March 2020, I recovered Ricka’s death certificate for 15 January 1948, aged 61 years, at Chiswick House, Pinner. She would have arrived in England by or before the age of 53; even in those days, hardly seriously advanced in years.

The cause of death is, however, not given as suicide. Rather the certificate reads: ‘Acute cystitis and pyelitis, due to generalised arteriosclerosis certified … after post mortem without inquest.’ Private hospitals generally did not wish to have to record suicides and so risk reputational damage. Less clear is whether death would have necessarily resulted from the causes given.

Ricka may have initially found some solace, ironically, during the War years when she could spend time with her daughter and son-in-law, and the granddaughter on whom she doted. Ricka would be left in charge of Nicolette, sometimes overnight, while Gerti went up to London to visit Tom. But the couple’s return to London in late 1944 once again did not accommodate Ricka, either in or nearby their Chelsea home, where she could enjoy their company, or host bridge parties and musical evenings with her fellow immigrés.

Ricka’s life from 1938 onwards is one of increasing absences. Her husband’s death closely followed by the appropriation of her home (and home city) lead to further trauma when her escape to a new life fails to become one of the closeness to her daughter she’d desired. Instead, Ricka seems to become increasingly effaced and lifeless, as she surrenders her hopes. Denied an ongoing physical presence in her family’s daily life, kept at a distance, it is as though she ceased to exist long before her death.

There are no more ‘family’ albums in which she appears with those she fled 1000 miles to join, not even a surviving snapshot. Among the quantities of pictures Gerti couldn’t resist taking of Nicolette, often with her stepdaughters Susan and Lyndall (and their pet donkey, Jeremy and poodle, Jenny) there’s not a single one in which Gerti included—still less took a portrait of—her mother.

After further prompting from me during the writing of this piece, and much searching through her own family albums, Nicolette did find three-and-a-half images on a contact sheet. They appear never to have been printed up, and show Ricka holding her only grandchild, aged about 18 months. What is most immediately striking is how photographically bad the images are: poorly lit and composed, the final one cut half-way across. In two of them Ricka’s face is bleached by light directly onto her face; in the other two, she is half-obliterated by darkness. With her black hair now starkly winged with white, the portraits appear emphatically bled of colour.

Ricka does not look into the camera, and the focus is exclusively on Nicolette, as if Gerti only had eyes for her. Ricka looks strained, although in the photograph (figure six) there is affection as well as hesitancy in the way she holds her granddaughter. The final photo on the strip is of Nicolette with her other granny, Tom’s mother. The contrast to the preceding three is extreme. Here Nicolette and Granny are carefully positioned against a window with a bucolic view, warmly smiling at the photographer. The series came at the end of a film, as if to use it up, rather than to prepare a record capable of prompting visual reminiscence.

It may be reading too much into the portraits to ponder whether Gerti literally did not wish (or at the very least might not have wished) to see, or see into, her mother. Either that, or she did not care overmuch whether or not she had achieved an accomplished photograph. If, as seems likely, these are the last photographs we have of Ricka, this renders them particularly poignant.

Postscript

There is one further factor I only discovered thanks to Dr Kylie Thomas’ intervention near the end of my writing this paper. On 25 May 2021, she forwarded me the results of a search in the Yad Vashem Data Base of Names (of Jews incarcerated in concentration camps), and drew my attention to the fact that Ricka had had a younger cousin, Anastasius (Yakov) Haas, son of Adolf (Yitzhak). And that Anastasius had had a wife, Grete (née Loeffler).

According to Yad Vashem, the couple were seized from their Olműtz home at Dvořáková 20 and removed to the Czech concentration camp at Terezin on 4 July 1942. Four days later, on 8 July, they were transported directly to Maly Trostenets in Minsk, the capital of Belorussia and part of the USSR invaded by Germany. The same day, alongside Jews from Austria, Germany, Poland, the Netherlands and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, they were lined up in front of pits they had been forced to dig and shot in the back of the head. [13]

This information came as a complete shock to me. Although Gerti, Ricka’s daughter and my mother, almost never discussed her family and absolutely never in connection with the War, my elder sister was under the impression that Ricka, like Gerti, had been an only child and that her family was a small one about which nothing was known. Or, it turns out, nothing was told.

Attached to Anastasius’ death notice was a note dated 18 October 2016. It read: ‘My father, Anthony Hare, passed away in London in 2009. I am his daughter and wish to add my contact details’ It was signed Dr Ruth Gutmann. I tried every one of the contacts. The landline was disconnected, and my email bounced back. There was no reply to my letter of enquiry sent to the land address or to the message I left on the mobile phone. Although I had no prior knowledge of Anthony Hare, at least I had confirmation that Anastasius was both Ruth’s grandfather and Ricka’s cousin. And that Anton/Tony was Gerti’s cousin, her daughters’ cousin once removed.

Some months later, in October 2021, and having apparently reached a dead end in my attempt at continuing research, I received an unexpected phone call from Dr Gutmann. Having ensured that I was sitting down, she explained that she had just found my message on an old British mobile phone she had not been using since emigrating to Israel two years earlier. Having rediscovered it in a shoebox at the back of a cupboard and on the point of throwing it away, as an afterthought she checked if there were any messages. She found mine.

We had a long conversation, during which I learnt that Anastasius was not the only Haas relative of whom I knew nothing, but that one of his sons had—through a series of extraordinary adventures—survived the War to end up living in London, where he maintained a long family relationship with his cousin Gerti, some seven years his senior. Yet Gerti had never mentioned him to her daughters, and we have no recollection of ever meeting him. Anton was close enough to Ricka for them to correspond during the War, and for her to leave him some personal possessions in her suicide note, in effect, her Will.

Since then, the conversation has continued, expanded to include Ruth’s brother David (living near Perth, Australia), and sister Deborah (in Kingston-upon-Thames), as well as my sister Nicolette (in Gauting, near Munich). Through Ruth’s research we learnt that the Haas family was indeed a large one. So far, a total of 14 family members are known to have perished either in or on their way to camps. [14]

Also, among those who were deported in 1942/3, were Ricka’s father, Heinrich, as well as her 88-year-old mother, Marie—Hebrew name Miriam—who were murdered in Poland. From information provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum [USHMM], it emerges that Ricka also had three brothers: Rudolf (known as Rudi, her elder brother, born 18.02.1879), and two younger ones, Richard (born 1893), and Robert (1898), with his wife Hilda Loeffler, Grete Loeffler’s sister.

During the war Richard was living in France. He was deported on ‘Transport 18, Train 901-13 from Gurs Camp (France) to Auschwitz Birkenau, Extermination Camp, on 08/08/1942.’ [15] In 1944 Robert, together with his wife Hilde, was taken from their family home in Brno and transported to Terezin. Dr Gutmann has now registered Rudolf as a victim of the Shoah with the United States Memorial Museum and submitted a request for detailed information.

One can only imagine Ricka’s feelings, in a state of not knowing for certain what she dreaded to discover. Not only could matters hardly be worse at home in continental Europe, but Ricka must have felt deprived of the home she had so yearned to be a part of in England. All this together with rumours, if not precise confirmation, of her fate as the last survivor of two generations of her entire family must have been an almost unimaginable load to bear. Yet, as we see from her letters, she refrained from mentioning her fears or her grief, even to her daughter. Some things don’t even bear talking about when there seems nothing that can be done.

Small wonder, then, that Ricka took the only course she felt remained to her.

Notes:

[1] Her reception was facilitated by the Austrian Ambassador Georg Albert von und zu Franckenstein [1878-1953]. A career diplomat (having served at both the Russian and Japanese Courts, and in India and Italy, before joining the Austrian Embassy at the Court of St. James. Being an opponent of the Nazis, he lost his diplomatic position after the Anschluss.

[2] ‘Mein geliebtes Mäderle (varied at times to ‘Gertikind’)’ and signed ‘deine Mutterli.’ There remain no letters from Gerti to Ricka, but the occasional postcard omits the diminutive and addresses Ricka as ‘Mutti.’

[3] ‘Loving (literally, heartfelt) kisses, Daddy.’

[4] Letter dated 04.11.1936. [All dates given are those of posting since the letters only supply days of the week].

[5] He drove out from England with his brother Paul, an army captain. Since he had no German and only poorly-pronounced French, he brought the wedding proposal in a letter for Gerti to read aloud to her parents.

[6] A Register of Jewish Wealth and Property, in which all possessions were itemised and valued in Reichsmarks.

[7] RM[Reichsmark] 1000 in 1938 is the approximate equivalent of €5000.

[8] Modification or Variation on the Register

[9] According to information from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum website there were, in 1933, over 100,000 Jewish-owned businesses. Approximately half were small retail stores dealing mostly in clothing or footwear. Under a preceding ‘Law of Voluntary Aryanisation’, two thirds of Jewish-owned enterprises were put out of business or sold to non-Jews. Jewish owners, often desperate to emigrate or to sell a failing business, accepted a selling price that was scarcely 20 or 30 percent of its actual value.

[10] Although even this is uncertain. Between 1937-8, the Nazis’ process of ‘Aryanisation,’ which had already stripped Jewish people of the right to employment, further stripped from them the right to employ others. Segregation was finalised with laws forbidding ‘Aryans’ such as domestic staff from working in Jewish homes. Anna, in particular, remained in touch with Ricka, and Gerti would visit her whenever she returned to Vienna after the War. But if neither Anna nor Agnes ran the errand to the post/telegraph office, Ricka would have needed to find another trusted friend to do so putting them at risk

[11] I am grateful to German lecturer Mark Ogden for both the translations and exegeses of this text.

[12] It came addressed to ‘Sara’ Deutsch, following a recent law that all Jewish persons be known by the first name either of ‘Sara’ or ‘Israel,’ in order to render them immediately identifiable. Such a system is redolent of the further insult enslaved Africans suffered in having their birth names replaced by that of their new owner.

[13] According to the records at Yad Vashem, Transport Bk, Train Da 226 from Theresienstadt, Ghetto, Czechoslovakia to Maly Trostents, Minsk, Minsk, Belorussia (USSR) on 08/09/1942. They were shot that day.

[14] Their names are inscribed on the walls of the Pinkas Synagogue, Prague, there is the name of at least one of Ricka’s brothers, Robert, alongside the names of Anastasius and Grete. It reads: ‘Czech and Moravian Jews, victims of Nazi genocide between 1939-1945 … and to also commemorate the 153 Jewish communities in Bohemia and Moravia which were destroyed during the War.’

[15] Gurs (in southwest France) was established pre-War in April 1939, initially for Spanish Civil War refugees. It became the largest camp on French soil during the Holocaust. After the Allied liberation of France in August 1944, French officials used Gurs to house German prisoners of war and French collaborators. In June 2022, I found Robert’s name again recorded as inmates in the holding camp of Les Milles, outside Marseille, together with that of his cousin, Georges [both names as in the French]. From there, both men were transported to Gurs, then on to Auschwitz where they were murdered.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey