The Politics of Beyoncé’s Pregnancy: Re-articulating Lemonade’s Narrative Agency through the Public Construction of Black Motherhood.

by: Juliet Winter , September 12, 2018

by: Juliet Winter , September 12, 2018

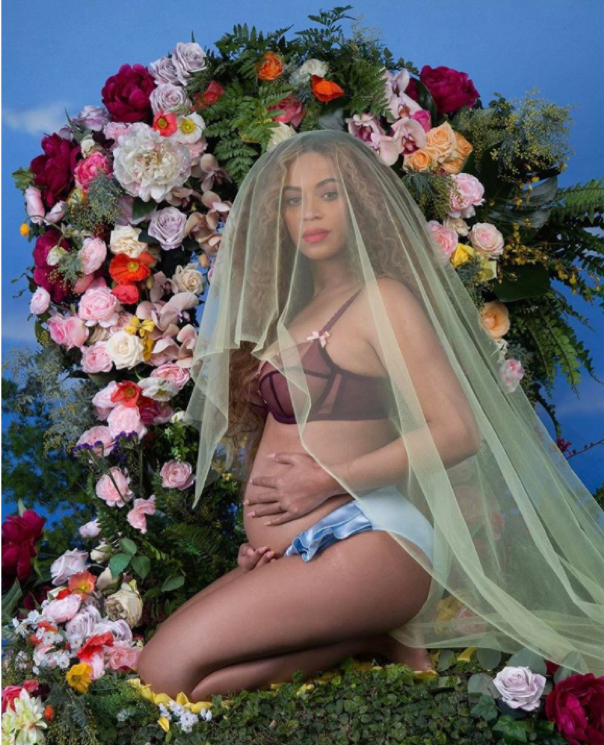

On the 1 February 2017, popular African American music artist Beyoncé announced her second pregnancy via a photograph posted to her Instagram page. Showing Beyoncé kneeling in front of an arc of flowers, wearing lingerie and a veil, and holding her bare pregnant belly, the photo became the most liked Instagram post of all time. Less than two weeks later, on the 12 February, Beyoncé performed songs from her 2016 visual album Lemonade at the Grammy Awards ceremony. The nearly nine minutes-long performance combined visual, audio and stage sequences that spoke to and rearticulated the themes of black womanhood and motherhood explored in the album, and – as with the Instagram photograph – featured numerous images of Beyoncé’s semi-nude pregnant body projected onto the stage. Despite Beyoncé missing out on the majority of the nine awards she was nominated for (she received only two: ‘Best Urban/ Contemporary Album’ and ‘Best Music Film’) as well as the chance to break the Grammy record for most Grammy wins by a female artist, journalists and social media users alike widely considered that her performance had stolen the show (as captured in an article by TIME Magazine which claimed that Beyoncé’s performance ‘made the internet lose its mind’). (Gajanan 2017) Beyoncé later curated both her pregnancy announcement and the award show performance on her website, with each having a dedicated photo album that further documented the events with additional and behind the scenes photographs.

In just under eight hours the Instagram photograph had been liked by over 6.3 million people and (at the time of writing this paper) has since reached 11.2 million Instagram ‘likes’. It remained the most liked Instagram photograph for nine months, until 12 November 2017 when it was surpassed by a photograph posted by footballer Christiano Ronaldo and later reality TV star Kylie Jenner. Both used the social media platform to announce the birth of their children.

Beyoncé Knowles Instagram pregnancy reveal: posted on 1 February 2017

While celebrity pregnancy reveals and magazine photoshoots have become common place in contemporary U.S. popular culture (a trend that infamously began with Demi Moore’s 1991 Vanity Fair cover) [1], what is perhaps most notable about Beyoncé’s pregnancy reveal and subsequent Grammy Awards Show performance are the ways in which she narrativised her pregnancy – and importantly, her pregnant body – and made it central to extending the visual narrative of empowered black womanhood explored in the Lemonade album. In both of these media events, Beyoncé not only comes to embody the Yoruba goddess Osun through the adoption of costume and other visual signs, but also seemingly finds strength in and imagines herself to be protected by the goddess during her pregnancy. That Beyoncé also aligns herself with other powerful African women figures in the photo album is significant. There are references to the ancient Egyptian queen Nefertiti, for example, in extracts of poetry that are featured in the pregnancy photo album and in the photographs themselves, with one featuring a bust of the Egyptian queen appearing alongside Beyoncé while she poses semi-nude and cradling her pregnant belly. The embodiment of Osun and the explicit references to the Nefertiti build upon similar iconographic references made in the 2016 visual album. Moreover, they align Beyoncé and her maternity with constructs of empowered black womanhood that exist historically, geographically and ideologically outside of the racialised formations of motherhood embedded in U.S. culture.

Focussing on the 2017 pregnancy reveal photographs and the Grammy Awards Show performance, this paper assesses the ways in which Beyoncé’s public construction and curation of her pregnancy and motherhood build upon the narrative agency of the Lemonade album. It first summarises our current critical understanding of the history of ideological formations of black motherhood in the U.S. and the contestation of these through visual mediums, specifically photography. Second, and within this critical context, it analyses how Beyoncé’s self-presentation of her maternity and motherhood can be understood within a historical trajectory of black feminist resistance through examining both Beyoncé’s re-imagining of the ‘Black Venus’ and the significance of maternal lineage (as explored in the narrative of Lemonade and re-produced in these two media events). This research forms part of a broader thesis which will consider how Beyoncé’s deployment of positively-coded representations of black maternity and motherhood can be read within the context of the very real crisis of black infant and maternal mortality in the U.S. [2] While important to acknowledge such debates here, analysis of these is beyond the scope of this paper and its situating of Beyoncé’s public construction and curation of her pregnancy within the trajectory noted above. Finally, I argue that through visual self-presentation, Beyoncé becomes not only a site of debate in relation to discourses of race, gender, identity and feminism, but emblematic of empowered black womanhood within the mainstream, dominant whiteness of American popular culture.

The Ideological Formation of Black Motherhood in the U.S.

In order to better comprehend Beyoncé’s self-presentation of her pregnancy and to situate this within our current critical understanding of ideological formations of black motherhood, it is first necessary to briefly summarise how the Lemonade album has been read to have constructed a narrative of empowered black womanhood. While the overarching narrative of the album revolves around marital infidelity and reconciliation, the visual component of the album offers a much more nuanced and complex story of black women’s historical and continued subordination and resistance – in which Beyoncé references her own African American heritage. With visual iconography that speaks to America’s slave history as well as historic and contemporary black liberation movements, it is the visual element of the album, and Beyoncé’s performance within it, that has been read as significant by both popular media and prominent black feminist scholars, including bell hooks (2016), Melissa Harris-Perry (2016) and Brittany Cooper (2016). For many of the commentators, Lemonade symbolised a long-awaited acknowledgment of the ways in which the intersections of racial and gendered oppressions have long shaped the collective experiences of not just African American women, but women of colour around the world. In a thought piece for ELLE Magazine online, Professor Brittany Cooper argued that Beyoncé had captured a narrative of black women’s survival that centred their maternal and intergenerational relationships as a site of empowerment. She stated ‘I love the multigenerational conversation that Bey constructs on this album… In the end, every Black girl I know is saved by what the Black women who came before her bequeath to her in the way of making a way out of no way’ (2017). While some, including black feminist scholar bell hooks, disagreed with this reading of the album, arguing instead that Beyoncé’s performative activism was an ineffective approach to addressing issues of race and gender discrimination, the album was undoubtedly the catalyst for such conversations about race, gender, identity and representation to be had within the whiteness of mainstream American popular culture. Moreover, that these conversations debated Beyoncé as a site of black female empowerment is significant when examining how she later constructed and curated her pregnancy, particularly with regards to the historical and ideological contexts in which she did so.

The fields of critical race theory and black feminist scholarship have long informed understandings of how America’s history of slavery and its surviving legacies have shaped constructs of racial and gendered identity. Historical enslavement, oppression and exploitation has continued to situate women of colour outside of, and in opposition to, prevailing (white) ideals of femininity and womanhood, the construction of which can be traced back to the American frontier and the Antebellum period. As Amy Kaplan suggests, while the white, European women of America’s frontier were ascribed the roles of homemaker, wife and mother, the feminisation of the domestic space inscribed exclusively white ideals of femininity and womanhood into America’s national narrative and notions of national identity. (Kaplan 1998: 582) Such racialised constructs of gender and ideologies of American womanhood are troubling, as famously highlighted by ex-slave and abolitionist Sojourner Truth at the Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. Truth reportedly [3] stated:

‘That man over there says women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?’ (cited in Collins 2000: 14)

Truth illustrates the paradox of being both black and a woman, recognising her exclusion from the privileges of idealised white womanhood and femininity on the grounds of her race and questioning racialised constructs of gender that serve to exclude her from the private sphere. While white women gained from the idealisation of their domestic virtues during this period – what bell hooks has called the ‘cult of womanhood’ (hooks 1982: 48) – women of colour remained trapped by the realities of their enslavement and subordination. In line with Kaplan’s observation that motherhood is a role ascribed exclusively to white women in their occupation of the domestic space, black women’s exclusion from this space in any autonomous capacity (historically only accessing it in the accepted capacity of work – through enslavement, domestic service and childcare) has in turn resulted in their exclusion from the virtues of idealised American maternity and motherhood.

Moreover, the legacies of the widespread sexual exploitation of women of colour, particularly the historical sexual exploitation of female slaves for the purpose of what hooks terms ‘breeding workers’ [4] (1982: 39), is of fundamental importance when examining constructs of black femininity and womanhood. The function of ‘breeding’ for economic purposes (providing a labour force for the production of so-called ‘cash crops’, notably cotton) situates constructs of black femininity within the ‘racialisation of the world of childbirth’ (Davies & Smith 1998: 56), and suggests that black maternity is deficient in the morality and sanctity of human procreation. The conception of black maternity here is oppositional to that of white maternity, constructed in white-dominated culture as virtuous and celebrated as essential in the construction of national identity. (Davies & Smith 1998; Kaplan 1998) In contrast, the situating of black maternity as necessary only for economic gain has long constructed it as unnatural and perpetuated harmful stereotypes of women of colour as ‘hyper-fertile’. In turn, that black maternity has historically served a capitalist and economic function – rather than a virtuous and essential one – has isolated it from the function of motherhood [5].

Identifying the distinction between constructs of black maternity and motherhood is important here. Unlike black maternity (that is, pregnancy and childbirth), which, although constructed as unnatural, has been normalised in American culture as a result of its historical economic purpose, black motherhood continues to be constructed as inadequate and insufficient. Persistent and damaging stereotypes, such as the ‘mammy’ [6], ‘welfare queen’ [7] and ‘matriarch’ [8] serve to reinforce notions of black motherhood in opposition to the virtues of white motherhood. Such racialised formations of motherhood continue to shape how black mothers are represented in contemporary U.S. society. For example, following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Melissa Harris-Perry argued that representations in mainstream media following the disaster reinforced negative racial stereotypes that situated black women as poor ‘refugees’ (Harris-Perry 2011: 14) and black mothers as shameful victims of a country that prides itself on wealth and prosperity. (2011: 19) Moreover, such notions extend beyond the figure of the black mother, as the black family also comes to be excluded from American ideals of the domestic space and family life. Patricia Hill Collins has observed that:

‘If one assumes that real men work and real women take care of families, then African-Americans suffer… black women become less ‘feminine’, because they work outside the home, work for pay and thus compete with men, and their work takes them away from their children.’ (Collins 2000: 47)

As Collins identifies, the black family disrupt traditional notions of family life as shaped by the feminisation of the domestic space (home) and the masculinisation of the non-domestic space (work). While this is also the norm for most white families in the U.S. in the 2010s (with women making up 46.8% of the U.S. labour force, according to a 2017 Pew Research Centre report), and has long been the norm for white working class women who have also historically worked outside the home, what Collins identifies here is the continued scapegoating of the African American family in relation to these gendered ideals, resulting in the stereotyping of black mothers and their black families as dysfunctional.

Such critical understandings of the ways in which black maternity and motherhood have been ideologically constructed in the U.S. throughout its history are of fundamental importance to any analysis of Beyoncé’s revelation and curation of her 2017 pregnancy. This critical context places Beyoncé and her pregnancy within the historical trajectory of the construction and contestation of notions of black motherhood, and, more broadly, on-going debates regarding discourses of race and gender. As a woman of colour occupying the public sphere, Beyoncé’s maternity and motherhood have previously been the subject of harmful racist commentary and speculation. During Beyoncé’s first pregnancy with her daughter Blue Ivy in 2011, rumours circulated in the American media – from celebrity gossip website TMZ to ABC’s News channel – that she had been wearing a fake pregnancy bump to conceal her use of a surrogate. Stemming from a TV interview with Australian news show Sunday Night, in which a fold in her dress caused some to question whether her bump was real, rumours suggested that Beyoncé was using a surrogate in order to preserve her body. The questioning of Beyoncé’s willingness to carry her own baby (although typical of celebrity media gossip – Katie Holmes and Nicole Kidman [9] are just two other examples of women celebrities who have been accused of ‘faking’ their pregnancies) perpetuated questions of inadequacy and dysfunction that continue to inform harmful stereotypes resulting from historical formations of black maternity and motherhood.

The premier of Beyoncé’s self-produced and directed documentary, Life is But a Dream, on HBO just over a year after giving birth to Blue Ivy responded to the commentary she had endured during her pregnancy and early motherhood. The documentary followed Beyoncé throughout her pregnancy and as she navigated a new direction with her music and management. It largely featured clips of home movies and performance footage, intersected with more formal interview-style scenes in which she talked about her career and motherhood. The visual documenting of Beyoncé’s changing pregnant body certainly contested rumours of surrogacy, with featured home-movie footage showing Beyoncé cradling her bare belly as well as silhouette footage of Beyoncé’s naked body during the later stages of pregnancy.

The featured black and white silhouette imagery is aesthetically significant. While audiences consuming the film are of course aware of Beyoncé’s blackness, the absence of race and the black body from these sequences presents Beyoncé’s pregnancy outside racialised constructs of maternity and motherhood by casting her body as a race-less silhouette. Moreover, the accompanying interview scenes and commentary feature Beyoncé talking about her experiences of becoming a mother, largely situating her motherhood as natural and God-given. She states: ‘This was life. I felt like God was giving me a chance to assist in a miracle. There’s something so relieving about life taking over you like that. You’re playing a part in a much bigger show, and that’s what life is.’ Through the use of black and white silhouette imagery and the description of her experience of motherhood in this way, Beyoncé – intentionally or not – challenged the construction of her maternity and motherhood as ‘fake’ and inadequate or unnatural by the media. This visual self-presentation enabled Beyoncé to re-define and self-determine the public image and narrative of her pregnancy and motherhood, aligning it with the qualities of virtue and essential-ness ascribed exclusively to ideals of white motherhood by a still dominant white American culture. Such visual contestation sits within a historical trajectory which has seen women (and men) of colour use visual mediums – such as film and photography – to construct representations of blackness which are self-determined and that challenge persistent damaging stereotypes.

Beyoncé’s 2017 pregnancy photographs should be read not only within the context of her earlier use of visual mediums to achieve an empowered self-representation, but within the wider and historical use of visual mediums as platforms through which narratives of black ‘otherness’ have been both reinforced and fought. Photography in particular has been historically significant in representing blackness in the U.S. Shawn Michelle Smith’s work suggests that photography was particularly important in establishing links between race and national identity in the nineteenth century, observing in the synopsis of her 1999 book, American Archives: Gender, Race and Class in Visual Culture, that: ‘photography and the sciences of biological racialism joined forces… to offer an idea of what Americans look like’, which emphasised whiteness and black ‘otherness’. However, photography has also served to help de-construct such racialised images. Through the use of props and costume, black subjects posing for photographs have historically adopted the ideals of white respectability and affirmed their place within what Smith calls ‘discursive fantasies of national character’. (Smith 1999: 5) Black activists, writers and intellectuals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Sojourner Truth, Fredrick Douglas, Ida B. Wells, and Frances Harper, are notable examples of figures who used photography (particularly the use and dissemination of the self-portrait or ‘carte de visite’) [10] as a means of respectable self-presentation. In their pictures they were forced to aesthetically adopt accepted standards of social respectability in order to gain the support of both black and white Americans in their public work and activism.

In the twentieth century, black artists and photographers during the Civil Rights period (from the 1950s to the 1970s) similarly used photography to contest images that perpetuated and upheld racist and sexist stereotypes. Black photography during the period – and notably within the growing Black Power and Black Liberation Movements – moved away from the adoption of costume and props that signified white notions of respectability, and instead embraced and celebrated blackness, the black body and what Kobena Mercer has called ‘ethnic signifiers’. (Mercer 1987: 37) [11] Deborah Willis and Carla Williams argue that black art and photography of the 1960s and ‘70s responded to ‘a politicised cultural climate’ (Willis and Williams 2002: 5), which endeavoured to re-define blackness outside of harmful racist stereotypes by taking control of black people’s images.

The celebration of the black body is thus a method of contestation. It is in understanding and situating the politics of the black body within racialised and gendered discourse that women and men of colour have been able to challenge and disrupt white hegemony and assert agency through visually embracing their blackness. (Cooper 2010; 41) This includes the bodies of pregnant black women, which when embraced by black artists and photographers during the 1960s, ‘70s and beyond (including Beuford Smith [12] and Renee Cox [13], among others) have drawn attention to what Willis and Williams call black women’s ‘pivotal role as perpetuator of the race’. (2002: 159) Consequently, black maternity has attained new meaning through the narrative agency of black photographers. Through visual representations, damaging stereotypes of black maternity and motherhood are contested, and both are instead constructed as fundamental to the ‘preservation of black life’. (Willis & Williams 2002: 160)

‘Mother Has One Foot in This World and One Foot in the Next’: Re-imagining the Black Venus

The construction and curation of Beyoncé’s 2017 pregnancy follows this trajectory of contestation, self-determinism and the celebration of black life. Unlike her 2011 documentary, her Instagram pregnancy reveal and the subsequent performance at the Grammy Awards Show go beyond aligning her pregnancy with ideals of white maternity and motherhood, and in doing so challenge damaging stereotypes of black motherhood and white notions of respectability. Instead, Beyoncé presents her maternity and motherhood outside of prevailing ideals shaped by dominant white culture, moving beyond the virtues of maternity and motherhood as ‘God-given’ to instead re-imagine her own self as a goddess. She does so by drawing on the narrative agency of the Lemonade album, and repeats visual and narrative signifiers that symbolise an empowered black womanhood to which Beyoncé’s maternity becomes central.

In particular, Beyoncé re-imagines herself as the Yoruba goddess Osun (or Oshun), [14] imagery which features heavily in the Lemonade album. Reviews in Time Magazine, American Vogue, and the digital news company Mic (among others) all read the iconography and costume featured in video sequences to the track ‘Hold Up’ to be Beyoncé’s depiction and/ or embodying of the goddess. Said to be the goddess of love and ‘sweet waters’, Osun is often depicted in art adorned in yellow and wearing gold and brass jewellery. (Murphy 2015: 120) In the video, Beyoncé embodies Osun through her costume (a yellow dress and gold jewellery), as well as in the underwater sequence that opens the track. In playing the part of Osun, Beyoncé elevates herself to the superhuman and empowered status of the deity and, in doing so, her own black womanhood, congruent with the divine and sacred womanhood of the goddess figure. That Osun is a Yoruba goddess demonstrates a diasporic consciousness (paying homage to an African culture connected to African American history through the slave trade and African diaspora) that acknowledges a potential ancestral and cultural heritage outside of America and its ideological formations of black womanhood. Thus, through Osun, Beyoncé is able to re-imagine and re-define black womanhood outside of white Eurocentric constructs of racial and gendered identity.

This iconography of Osun is also repeated in the pregnancy photo album featured on Beyoncé’s website. The collaboration between Beyoncé and photographer and artist Awol Erizku [15] draws upon the same visual signifiers used in Lemonade to symbolise the goddess throughout the images: from underwater shots of a semi-nude Beyoncé draped in yellow cloth which echo the underwater sequences in Lemonade, to the use of the colour yellow as the backdrop in all of the colour images in the shoot. Similarly, yellow features repeatedly in the Grammy Awards performance. Beyoncé drapes her pregnant body in yellow cloth, a sheer gold beaded dress featuring the subtle image of a goddess over the belly, and a gold crown and copious gold bangles around her neck and wrists.

Furthermore, these visual references to the goddess are explicitly acknowledged in the accompanying extracts of poetry written by Beyoncé in collaboration with British poet Warsan Shire. [16] The collaboration between Beyoncé and Shire here is a continuation of their partnership on the Lemonade album, with Shire’s poetry having featured throughout the album’s narration [17]. The poetry featured in the pregnancy photo album names Osun directly, alongside Yemoja, the mother of Yoruba gods and goddesses, and Nefertiti, the ancient Egyptian queen. The extract reads: ‘In the dream I am crowning. Osun, Nefertiti and Yemoja pray around my bed’, suggesting that in Beyoncé’s own imagining of the birth of her children, the goddesses become her birthing partners. It is, of course, necessary to acknowledge her adoption of Yoruba culture and references to figures from other African histories and cultures, given that Beyoncé has appropriated them for commercial (and seemingly personal) self-affirmation (see Hobson, 2015) [18]. However, this is perhaps necessary in her attempt to construct her maternity and motherhood outside of dominant white culture and prevailing systems of racial hierarchy. Her alignment with the goddesses repeats the visual iconography of Lemonade which similarly re-imagines empowered black womanhood, building upon this in a way that situates black maternity and motherhood as sites of empowerment, rather than inadequacy or dysfunction.

Furthermore, Beyoncé also re-imagines western equivalents of these African figures, perhaps most notably the figure of Venus. The pregnancy photo album includes an extract of poetry which reads: ‘girl turning into woman, woman turning into mother, mother turning into Venus’, referring to Venus as the ultimate figure of empowerment in the evolution of womanhood. The Roman goddess of fertility, beauty and love, the image of Venus has been repeatedly re-imagined in European art and literature. Thought of as the counterpart of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, the image of Venus has been defined by Eurocentric notions of beauty, sexuality and feminine virtue, particularly during the Renaissance period (Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus is a notable example). The Venus figure has also come to be closely linked with notions of love, as Catherine Belsey argues, stating that ‘the enigmatic nature of love is widely registered in the representation of the goddess’. (Belsey 2012: 185) Belsey further argues that it is love that has been long ‘perceived as civilising in its effects’ (2012:179), suggesting that notions of love and myths of Venus are closely linked with ideas of civilisation that are Eurocentric in their construction and dissemination.

Such notions of the Venus figure have historically shaped formations of both white and black womanhood. The ‘Sable Venus’ and ‘La Vènus Noire’ (or the ‘Black Venus’) in which the exoticised black female body became the object of sexual desire – what Willis and Williams call ‘a depersonalised object of colonial lust’ (Willis and Williams 2002: 9) – emerged during the spread of European imperialism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The sexualised black female or black mistress is constructed in opposition to the virtues of European womanhood, with historical figures such as Jeanne Duval [19], Saartjie Baartman [20], and later Josephine Baker [21], all acquiring in one form or another the nickname ‘Venus’ in their representations as infamous mistress, exhibit attraction and performer respectively. Furthermore, the harmful ‘Jezebel’ stereotype, which is a construct of black womanhood that represents black women as hypersexualised, lustful and promiscuous (counter to the self-respect and virtue that has shaped white womanhood) – has been shaped by notions of the Black Venus that emerged from colonial and slave histories.

The significance of Beyoncé’s reference to the Venus figure in the construction of her maternity and motherhood is twofold. First, she aligns her embodiment of Venus with the virtues of beauty, fertility and love that are associated with the Roman goddess; situating Venus alongside Osun and embodying both in an empowered re-imagining of her own womanhood. In doing so, Beyoncé disrupts the construct of the Black Venus as an exoticised and sexualised object of white men’s desire, instead centering her semi-nude pregnant body as a symbol of divine and empowered motherhood. The semi-nudity of Beyoncé’s pregnancy photographs and performance at the Grammy Awards Show works to embrace and showcase the empowered black female body, controlling its visibility and resisting racist and sexist constructions of black womanhood (as argued by Cooper). Second, and building on this, the semi-nudity of Beyoncé’s self-presentation of her pregnancy coincides with Willis and Williams’s reading of black women’s visible, pregnant bodies as demonstrating the celebration of ‘nothing less than black life itself’. (2002: 160) Beyoncé’s semi-nudity emerges from a rich history of photographic representations of black maternity and motherhood as self-determined and celebrated. Rather than re-embodying the Jezebel stereotype, Beyoncé’s self-presentation of her pregnancy challenges it and instead demonstrates and celebrates empowered black womanhood and motherhood through the pregnant black body itself. Such online and on-stage representations of empowered black maternity come to hold further significance when situated alongside broader notions of empowered black motherhood which emanate through narratives of maternal lineage in the Lemonade visual album.

Maternal Lineage and the Empowered Black Mother

Throughout Lemonade Beyoncé frequently situates her performances within communities of black women, from dance sequences during the track ‘Formation’ which speak to the iconography of the Black Panther Party,[22] to scenes on a southern plantation where communities of black women wear nineteenth century-style dresses. Beyoncé’s centring of self within the collective of shared black womanhood draws upon well-established yet subtle forms of black feminist resistance. As Collins has observed, it is in black women’s relationships with one another that a ‘safe space’ (2000: 102) is created in which self-affirmation becomes attainable within dominant systems of whiteness and patriarchy. Additionally, Collins proposes that it is the mother-daughter relationship that is crucial in resisting racial and gendered stereotypes, stating that ‘countless mothers have empowered their daughters by passing on the everyday knowledge essential to survive as African American women’. (2000: 102) Her conceptualisation of the importance of black women’s relationships, particularly with their mothers, is one that has been previously realised and explored by African American women artists, such as writers Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. [23]

Beyoncé rearticulates such narratives in Lemonade, perhaps most explicitly in a sequence whereby she narrates a lemonade recipe which fuses into a dedication to a grandmother figure. She narrates:

Take one pint of water. Add a half pound of sugar, the juice of eight lemons.

The zest of half lemon.

Pour the water from one jug, then into the other, several times.

Strain through a clean napkin.

Grandmother, the alchemist.

You spun gold out of this hard life.

Conjured beauty from the things left behind.

Found healing where it did not live.

Discovered the antidote in your own kitchen.

Broke the curse with your own two hands.

You passed these instructions down to your daughter.

Who then passed it down to her daughter.

The lemonade recipe that Beyoncé recites here is framed as a set of instructions to be passed down to daughters and granddaughters in turn, giving them the ingredients necessary to resist and overcome the intersectional oppressions that have shaped their experiences as black women. Beyoncé’s narration pointedly yet subtly draws attention to black women’s collective experiences of oppression through references to healing and surviving what she calls ‘this hard life’. She simultaneously positions the grandmother as a protective figure, passing down instructions to her daughters and granddaughters that will allow them to break ‘the curse’ of their oppression. This point is further illustrated in the home-video clip that follows the instruction sequence, in which Beyoncé’s grandmother-in-law, Hattie, gives a speech at her ninetieth birthday celebrations. Hattie states, ‘I had my ups and downs but I always found the inner strength to pull myself up. I was served lemons but I made lemonade’. Hattie is both the literal and figurative grandmother figure here, and she uses the metaphorical process of making lemonade to connote her inner strength and ability to ‘pull herself up’. Hattie’s account of transformation and transcendence as that which has resulted from her own strength again speaks to the notion of the grandmother figure as protector, as outlined above, and can be aligned with Willis and Williams’ reading of black women as perpetuators of the race and protectors of black life.

The narratives of maternal lineage explored in the Lemonade album are repeated in the pregnancy photo album and Grammy Award’s performance. In the photo album, images from Beyoncé’s pregnancy photoshoot are situated alongside photographs of her grandmother, mother and daughter. In the gallery, there are photographs of Beyoncé’s grandmother holding her then infant mother, as well as one photograph featuring her mother, Tina, pregnant with Beyoncé, and a sequence of photographs of Beyoncé’s first pregnancy with her daughter Blue Ivy (showing her growing belly between the five and nine month stages). The curation of her second pregnancy within this personal narrative of maternal lineage situates the mother-daughter relationship as essential to black women’s self-affirmation and empowerment, building upon the symbolism of the Grandmother and her story in the Lemonade album.

As with the pregnancy reveal photo album, Beyoncé’s Grammy Awards Show performance also featured a narrative of maternal lineage. As the performance began, images of a semi-nude and pregnant Beyoncé were projected onto the stage. The projections showed Beyoncé holding her bare pregnant belly, visually mirroring the Instagram pregnancy reveal, while she read Shire’s poetry (as featured in Lemonade) in voiceover. As Beyoncé recited the words ‘do you remember being born?’ and ‘are you thankful for the hips that cracked. The deep velvet of your mother, and her mother, and her mother’, more and more women of colour appeared in the projection, draping Beyoncé in veils and sitting or kneeling beside her. The projection cuts to a still semi-nude Beyoncé sitting alongside her mother Tina and her daughter Blue Ivy. Sitting in linear order, from Tina to Beyoncé to Blue Ivy, the three figures appear largely isolated from the women who previously filled the stage. This shift in focus highlights Beyoncé’s role as both mother and daughter, and constructs her pregnancy within a visual representation of maternal lineage. That the performance repeats the poetry featured in the Lemonade album makes these narrative links explicit, aligning the album’s themes of empowered black womanhood with Beyoncé’s construction of her pregnancy in the performance.

As with the pregnancy reveal, the repetition of the visual and narrative iconography of Lemonade through the construction and curation of Beyoncé’s pregnant body portrays black motherhood as empowering. By extending the narrative of Lemonade through these two media events, Beyoncé challenges ideological formations of black motherhood as dysfunctional, and instead re-defines and re-envisions it as essential in the preservation, protection and celebration of black life. Crucially, she does not achieve this by aligning her maternity and motherhood with white ideals of womanhood and domesticity, but instead situates the essentialness of her pregnancy within black feminist thought that champions black mothers and maternal lineage as sites of strength and resistance. As a result, her construction of black maternity and motherhood becomes not only essential, but empowered and empowering.

Conclusion

Beyoncé’s self-presentation of her 2017 pregnancy through her online platforms and the Grammy Awards performance sit within a trajectory of the visual contestation of harmful ideological formations of black motherhood. The repetition of visual and narrative signifiers from the Lemonade album extend and build upon the themes of empowered black womanhood that Beyoncé has come to symbolise within the still dominant whiteness of mainstream American popular culture. Her embodiment of and alignment with figures of empowered black womanhood that exist outside of the U.S. and its racialised constructs of femininity, womanhood and motherhood, disrupt the continued construction of black maternity and motherhood as dysfunctional, instead re-defining it outside the parameters of racial hierarchy and white ideals. Furthermore, the construction of black maternity and motherhood as a site of empowerment contests the historical disempowerment of black women in the U.S. (and beyond) through sexual exploitation and exclusion from the private sphere. As a result, Beyoncé’s pregnant body comes to be a site of political and cultural agency that asserts certain principles of black feminist resistance. Moreover, the construction and curation of her pregnancy via these two media events extends existing dialogue that regards Beyoncé as emblematic of empowered black womanhood, and an agent of debate in discourses of race, gender, identity, feminism and representation.

Notes

[1] Demi Moore, seven months pregnant at the time, posed nude for the cover of the August 1991 edition of Vanity Fair. It was the first magazine cover to feature a nude pregnant celebrity, which at the time was unprecedented. It was the high end readership of the magazine and the cultural capital of the photographer Annie Leibowitz that seemingly allowed for the publication of the image. The photograph made TIME Magazine’s 100 most influential images of all time because of both the controversy surrounding it and the cultural shift that followed, which has seen numerous women celebrities follow in Moore’s footsteps.

[2] The crisis of black infant and maternal mortality has been widely reported in the U.S. media, as evidenced in a recent reported featured in the New York Times Magazine which claimed that this racial disparity is worse than in the 1850s, before the abolition of slavery.

[3] It was reported sometime after the event that Sojourner Truth asked her audience ‘Ain’t I am Woman?’, however we do not know what she actually said at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851.

[4] Slave laws in the United States deemed that the children of slaves were born slaves. As such, the ‘breeding’ of slaves to buy and sell for economic gain (growing the labour force) was the usual practice, particularly on the plantations of the American south. Breeding slaves was cheaper than importing them from Africa.

[5] It is important to note here that while maternity and motherhood have been imagined and celebrated as essential in the construction of national identity in the U.S., pregnancy itself has historically maintained a taboo status. With the pregnant belly becoming a visible indication of women’s sexuality and sexual activity (contradicting ideals that have defined white womanhood as virtuous and non-sexual), pregnant women have, until relatively recently, been required to retreat from public life to the private and domestic space. While the same taboo has existed for black women in the U.S. (as constructed from white ideals of womanhood and femininity), their exclusion from the domestic space and the economic function of pregnancy have served only to further reinforce harmful stereotypes that situate black women has ‘hyper fertile’ and black maternity as ideologically oppositional to white maternity.

[6] The ‘Mammy’ stereotype has historically imagined black womanhood in line with the archetype of the black housekeeper and/ or nanny figure. The Mammy is often represented as an older, dark-skinned and overweight black woman (although not always) and is often a submissive and maternal figure who is loyal to her white family. The Mammy remains largely outside of her own home and family unit because of her domestic service within the white household.

[7] The ‘Welfare Queen’ stereotype depicts poor black mother or black single mothers, often demonising them as figures who manipulate the American welfare system for their own gain.

[8] The ‘Matriarch’ stereotype imagines black mothers as aggressive, controlling and opinionated. In addition, it situates black mothers as lacking in the ideals of submissive femininity and motherhood, instead often characterising black mothers as ‘bad’ wives who emasculate their husbands and do not conform to the ideals of traditional family life.

[9] Holmes and Kidman have both been accused by the tabloid media of faking their pregnancies. In 2006, tabloids and celebrity gossips sites, such as E! News, questioned whether Holmes was pregnant because her stomach appeared to be growing and shrinking. Similarly, in 2008 Kidman was accused of wearing a fake bump while her sister acted as her surrogate.

[10] The use of ‘cartes de visite’, small portrait photographs designed to be given to family, friends and associates, were particularly popular in America during the Civil War period in the 1860s. For African Americans during the nineteenth century, cartes de visite became a cheap and easily accessible form of self-portrait photography, with figures (including those noted here) selling their cartes de visite self-portraits at public speaking engagements as a means of disseminating their work and attracting the support of audiences.

[11] Mercer situates the use of ethnic signifiers – such as ‘natural’ afros, dashikis, and gele wraps – as a means of exhibiting diasporic consciousness and resisting or rejecting systems of whiteness and Eurocentric standards of respectability and beauty.

[12] Notably, Smith’s ‘Woman Bathing/ Madonna’ photograph, shot in New York in 1967. The photograph features a naked, pregnant woman of colour standing on a New York rooftop in the rain. It was featured in the 2017 Soul of a Nation exhibition at the Tate Modern art gallery in London, UK.

[13] Cox’s ‘Yo Mama’ series has been said to represent the power of black motherhood. Photographs including ‘Yo Mama and the Statue’ (1993) have been read by Deborah Willis and Carla Williams as Cox presenting ‘heroic views of herself as a black woman, mother and artist’. (2002: 153)

[14] The Yoruba peoples are an ethnic group from what is now the Nigerian and Benin areas of West Africa.

[15] Awol Erizku is an Ethiopian-born artist and photographer whose work focusses on challenging the white aesthetic of the art world. The aesthetics of Beyoncé’s pregnancy photoshoot continue through some of his other recent work, which can be seen on his website.

[16] Warsan Shire was named London’s first Young Poet Laureate in 2014. Her poetry often speaks to experiences of immigration, motherhood and feelings of being displaced or ‘homeless’, reflecting her own experiences of emigration. The use of Shire’s poetry throughout the Lemonade album seems to align the themes in Shire’s work with the collective or shared experiences of African American women to which the album speaks.

[17] Beyoncé credited Shire with ‘Film Adaption and Poetry’, recognising their collaboration on the album.

[18] The power and prominence of the African American diasporic experience and cultural influence arguably affords African Americans relative privilege when it comes to the sharing and adopting of African cultures. Given this, on-going debates regarding the adoption of African cultures and cultural practices by African Americans examines how far this may be considered an act of cultural appreciation and a demonstration of diasporic consciousness, or an act of cultural appropriation and re-invention.

[19] Jeanne Duval was a Haitian-born actress who became famous as the mistress and muse of French poet, Charles Boudelaire in the nineteenth century. Boudelaire gave Duval the nickname ‘La Vènus Noire’.

[20] Saartjie Baartman was born in the British Cape Colony (now South Africa) in the late eighteenth century, and was subsequently brought to Europe to be exhibited in freak show attractions. She became famous for her large buttocks and was nicknamed the ‘Hottentot Venus’. The public exhibition and representation of Baartman’s body was used as, and fed into, the science of biological racism that was prominent during the era.

[21] Josephine Baker was an Africa American singer, dancer and entertainer who found success and fame during the 1920s – particularly in Paris. She was well-known for her revealing costumes, energetic dances and ‘exotic’ beauty. She famously performed (and was photographed) wearing a banana skirt, exemplifying notions of ‘exotic’ blackness for her predominantly white audiences. She adopted the nickname ‘Black Venus’.

[22] As Kobena Mercer describes, the ‘urban guerrilla attire’ which ‘encoded a uniform for protest and militancy’ (Mercer 1987: 39) has become symbolic of the Black Panther Party – an organisation founded in California in 1966 that believed in racial pride and demonstrations of ‘black excellence’ as a means of ‘bettering’ African American communities and achieving self-determinism within a society that continued to privilege whiteness. The wearing of the afro hairstyle and the uniformity of the costume featured in this dance sequence certainly re-imagine the ‘urban guerrilla’ uniformity of the Black Panther Party (something Beyoncé also re-imagined during her 2016 Super Bowl performance).

[23] Writers such as Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou have often focussed their exploration of African American women’s oppression and resistance through the mother-daughter relationship, notably in Morrison’s Beloved and Angelou’s Mom & Me & Mom.

REFERENCES

Angelou, Maya (2013), Mom & Me & Mom, London: Virago.

Belsey, Catherine (2012), ‘The Myth of Venus in Early Modern Culture’, English Literary Renaissance 42: 2, pp. 179-202.

Casablanca, Ted (2008), ‘Two Kidmans, a Baby and the Anatomy of a Rumor’, E! News, 4 December 2008, https://www.eonline.com/news/71566/two-kidmans-a-baby-and-the-anatomy-of-a-rumor (last accessed 24 April 2017).

Collins, Patricia Hill (2000), Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York; Routledge.

Collins, Patricia Hill (2006), From Black Power to Hip Hop: Racism, Nationalism, and Feminism, Philadelphia; Temple University Press.

Cooper, Brittany (2010), ‘A’n’t’ l a Lady?: Race Women, Michelle Obama, and the Ever-Expanding Democratic Imagination’, MELUS, The Bodies of Black Folk, 35: 4, pp. 39-57.

Cox, Renee, ‘Yo Mama’ collection: http://www.reneecox.org/yo-mama (last accessed 20 April 2018).

Davies, J. & Smith, C. (1998), ‘Race, Gender, and the American Mother: Political Speech and the Maternity Episodes of I Love Lucy and Murphy Brown’, Journal of American Studies, 39: 2, pp. 33-63.

Erizku, Awo. Official website: http://www.awolerizku.com/ (last accessed 24 April 2018).

Fetterolf, Janell (2017), ‘In Many Countries, At Least Four-In-Ten In Labour Force Are Women’, Pew Research Centre. 7 March 2017, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/07/in-many-countries-at-least-four-in-ten-in-the-labor-force-are-women/ ((last accessed 25 May 2017).

Gajanan, Mehita (2017), ‘Beyoncé’s Grammy Performance Made the Internet Lose its Mind’, TIME Magazine online. 13 February 2017, http://time.com/4668455/grammys-2017-beyonce-performance/ (last accessed 23 April 2018).

Gornstein, Leslie (2006), ‘Did Katie Holmes Fake Her Pregnancy?’ E! News. 29 April 2006, https://www.eonline.com/news/58134/did-katie-holmes-fake-her-pregnancy (last accessed 25 May 2017).

Harris-Perry, Melissa (2011), Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, London: Yale University Press.

Harris-Perry, Melissa (2016), ‘A call and response with Melissa Harris-Perry: The pain and the power of ‘Lemonade’’, ELLE. 26 April 2016, http://www.elle.com/culture/music/a35903/lemonade-call-and-response/ (last accessed 25 May 2017).

Hobson, Janell (2015), ‘Between Diasporic Consciousness and Cultural Appropriation’, Black Perspectives. 3 October 2015. http://www.aaihs.org/between-diasporic-consciousness-and-cultural-appropriation/ (last accessed 25 May 2017).

Hobson, J. and Bartlow, D. (2008), ‘Representation’: Women, Hip Hop, and Popular Music’, Meridians, 8:1, pp. 1-14.

hooks, bell (1981), Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, London; Pluto Press.

hooks, bell, Panellist in The New School talk, ‘Are you Still a Slave: Liberating the Black Female Body’, New York, 2014, https://livestream.com/accounts/1369487/events/2940187/videos/50178872/player?autoPlay=false&mute=false (last accessed 10 November 2016)

Kaplan, Amy (1998), ‘Manifest Domesticity’; American Literature, 70: 3, pp. 581-606.

Knowles, Beyoncé. Instagram (2017), ‘We would like to share our love and happiness. We have been blessed two times over. We are incredibly grateful that our family will be growing by two, and we thank you for your well wishes — The Carters, 1 February 2017. https://www.instagram.com/p/BP-rXUGBPJa/?hl=en&taken-by=beyonce (last accessed 25 May 2017).

Knowles, Beyoncé. Official Website, Parkwood Entertainment. www.beyonce.com (last accessed 25 May 2017).

Lewis, Phillip (2016). ‘Theory Involving the African Goddess, Oshun, is Mind Blowing’, MIC. 25 April 2016. https://mic.com/articles/141799/this-beyonc-lemonade-meaning-theory-involving-the-african-goddess-oshun-is-mind-blowing#.9cPQ7Nq9u (last accessed 16 June 2016).

Mercer, Kobena (1987), ‘Black Hair/ Style Politics’, New Formations, 3, pp. 33-54.

Morrison, Toni (1987), Beloved, London: Vintage Books.

Murphy, Joseph M. (2005) ‘Osun across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas’, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, 8: 3, pp. 120-121.

Sanders, James R. (2016) ‘Beyoncé’s Oshun and Lemonade’, Vogue. 16 May 2016, http://www.vogue.it/en/fashion/news/2016/05/16/beyonce-oshun-and-lemonade/ (last accessed 20 June 2017).

Smith, Shawn Michelle (1999), American Archives: Gender, Race and Class in Visual Culture, New Jersey; Princeton University Press.

Smith, Shawn Michelle, ‘American Archives: Gender, Race and Class in Visual Culture’, Princeton University Press online. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/6733.html (last accessed 12 June 2017).

TIME: 100 Photos, Demi Moore (2017), http://100photos.time.com/photos/annie-leibovitz-demi-moore (last accessed 16 April 2018).

Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha (2016), ‘Beyoncé’s Lemonade is Black Woman Magic’, Time Magazine, 25 April 2016, http://time.com/4306316/beyonce-lemonade-black-woman-magic/ (last accessed 12 June 2017).

TMZ, (2011), ‘Beyoncé: Stomach Folding Video Ignites Pregnancy Conspiracies’. 10 November 2011 http://www.tmz.com/2011/10/11/beyonce-stomach-video-fake-pregnancy-pregnant-jay-z-australian-talk-show-fold-in-bump-coverup-rumors-collapses-inward/ (last accessed 25 May 2018).

Villarosa, Linda (2018), ‘Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies are in a Life-Or-Death Crisis’, The New York Times Magazine. 11 April 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html (last accessed 16 May 2018).

Willis, Deborah.& Carla Williams (2002), The Black Female Body: A Photographic History, Philadelphia; Temple University Press.

Winter (née Williams), Juliet (2016), ‘Beyoncé’s Lemonade: A Complex and Intersectional Exploration of Racial and Gendered Identity’, U.S. Studies Online; The British Association for American Studies, 6 June 2016, http://www.baas.ac.uk/usso/beyonces-lemonade-a-complex-and-intersectional-exploration-of-racial-and-gendered-identity/ (last accessed 16 May 2017).

Films/TV programmes

Lemonade, Visual Album, Beyoncé Knowles. USA: Parkwood Entertainment, Columbia, 2016.

Life is but a Dream, documentary film, directed by Beyoncé Knowles, USA: Parkwood Entertainment, 2013.

Knowles, Beyoncé. Performance at 59th Annual Grammy Awards, USA, CBS, 2017.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey