The Decolonising Tunisian Woman in Salma Baccar’s ‘Fatma 75’

by: Yasmine Benabdallah , December 13, 2021

by: Yasmine Benabdallah , December 13, 2021

Half a century ago, Salma Baccar made Fatma 75, the first feature film directed by a Tunisian woman. An essay film that crosses genres and bends time, the film intertwines histories of feminism and resistance against colonisation in Tunisia, drawing from such events as the early matriarchal indigenous resistance against the Arab conquest, to the 20th century Muslim feminist resistance against the French colonisers.

Salma Baccar says that the film was a way for her to tell ‘everything [she] had in [her] heart about women,’ wanting to show ‘that women’s emancipation, although written in the Tunisian Constitution, [had] entered neither mentalities nor customs’. (Baccar 2009)

Upon studying film in France, Baccar returned to Tunisia and joined a local film club. At that time in recently independent Tunisia, amateur film clubs were a space for young artists and intellectuals to think about their country’s future in feminist, political, and revolutionary ways, echoing the effervescence of student movements. Fondly remembering the film club days, Salma Baccar told Stefanie Van de Peer, ‘[t]he film club was an amazing circle of friends; we did everything together and supported each other’s work. There was absolutely no funding available for us, so we did everything ourselves’. (Van de Peer & Baccar 2011: 474)

While Fatma 75 was originally funded by the Tunisian ministry of culture as a way to celebrate women’s rights in Tunisia in the context of the 1975 UN International Year for Women, the completed film was censored for thirty years by the government itself. The censorship was a way for the modernist and neo-colonial government led by then-president Habib Bourguiba to maintain his image of the saviour of women, and to silence the female anger the film carries. (Rouxel & Baccar 2016)

Upon Tunisian independence in 1956, women who had fought alongside men in the decolonial struggle, expected their fight to be recognised and to be granted full equality. Decolonisation came, and the first independent Tunisian government granted some, but not all equal rights. That way, the government took on the image of a progressive feminist regime and established state-feminism, all while silencing the people’s feminist community-led struggle. (Mahfoudh 2014: 14)

Bourguiba was responsible for a ‘culture of political patriarchy’. (Mhadhbi 2012) Women affiliated to his political party, the Neo-Destour, were the only ones allowed to express themselves publicly on women’s issues. ‘By effectively outlawing other forms of political leadership, Bourguiba stalled the women’s movement in its broader fight for autonomy from male authority’. (Mhadhbi 2012) After this, there followed two decades of waiting for change, only for women and other dissident communities to realise that their needs and demands were not going to be met unless the fight continued.

That is the context in which Fatma 75 was made, a feminist manifesto made by a woman, about women, calling for new feminist narratives and a revival of the feminist struggle. Today, as the public-space-reclaiming feminist movement Ena Zeda is gaining momentum in Tunisia, more than 70,000 Tunisian women have come forward to denounce sexual harassment and gender-based violence of all kinds. Today, Fatma 75 speaks loudly of the freedom in decolonisation, in both its construction as a work of art, and its discourse in the context of Tunisian history.

The film is a historiography of the feminist struggle for decolonisation, reclaiming the narrative for Tunisian women, away from both the coloniser’s hand and from state-led feminism. It records the different collectivities as well as language practices of the time, as testimonies of social and political dynamics. The film is not bound by a linear sense of space or time, the narrative jumps feeling like multiple introductions to different potential Tunisian feminist narratives. In that way, it is a call for stories, its censorship sadly all the more impactful.

The curating team of the Africa in Motion film festival, where the film was screened in 2017, writes, ‘[o]fficially, the censorship occurred because of the depiction of an explicit sexual education lesson, although it is more likely that the film was banned because of its politicised voice-over and indirect critique of propagandistic policies’. (AiM 2020) I read this and think about a number of Moroccan films that were censored or banned post-independence, in particular during the Years of Lead’—a period of Moroccan history marked by state surveillance and repression—because they were considered to be doing a disservice to the building of a cohesive national identity.

I was born and raised in Morocco, and have recently come back to make films here, after living in France for a few years, so watching and writing about Fatma 75 feels, in many ways, personal. My cultural and geographical proximity to Tunisia growing up allows me to understand certain aspects of Tunisian society, in particular the decolonial experience, as well as certain subtleties in language and the politics behind the choice between using one’s own dialect, standardised Arabic, or French.

Yet there are crucial differences between where I am from and where the film takes place. Growing up as a Moroccan girl, there was always an imaginary of freedom and female emancipation linked to Tunisia. I remember that my father told me, when visiting Tunisia at the age of nine, that they had better access to education, and hence were more accepting more forward-thinking, which meant that they were closer to the ways of the West. Only as an adult did I start to understand the intricacies of the situation, and the feminist fight’s instrumentalisation that was at play.

There is also a gulf in time between me and the film: 1975 to 2021, nearly half a century of political change and shifts in cultural perspectives, of which my generation is the result. I will never fully understand what it was to make or watch Fatma 75 at the time when it was censored, will never feel the urgency of its manifesto in real time. I am watching it now, with the knowledge of the progress and the setbacks that the women of Tunisia and the rest of our region have experienced, as well as the complex dynamics we have with our past colonisers.

Salma Baccar made Fatma 75 in a specific context, but the question remains—even as I write this—of how to reach a balance between being women critical of our own societies and governments and avoiding the perpetuation of the western neo-colonial projected views of our communities.

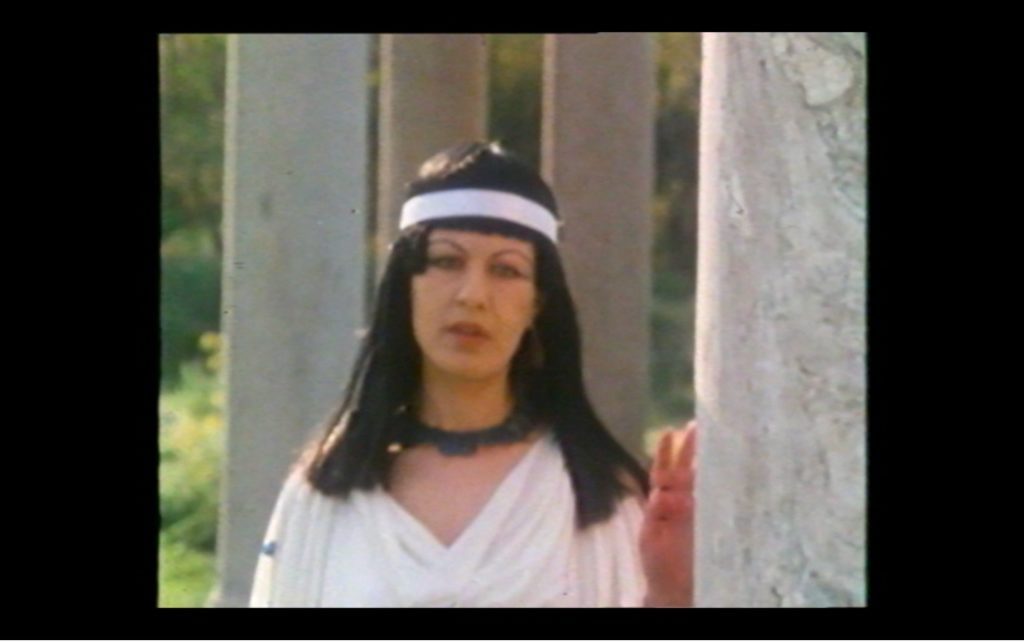

The film opens with an-out-of-focus image of a woman theatrically walking towards the camera, surrounded by the columns and nature of Carthage’s Roman ruins. Once in focus, she says her name, ‘Sophonisbe,’and speaks of her allegiance to the land, telling us ‘my home is Carthage.’ She introduces herself as a native queen of Tunisia from Roman times. This native queen is a Tunisian woman who fights for her land. Her opening speech sets the tone for the film: the right to the land and to equality with men. The freedom of the land can only go hand in hand with the freedom of woman. As the same actress—Jalila Baccar—reappears, she speaks of Kehna, another queen known in history to have defended North Africa from the Arab conquest. She speaks directly to the camera.

In 1975, film in Tunisia—as in many other places—had been a largely male-dominated art form, and was finally seeing more women filmmakers take up the camera and tell their own stories. Baccar, like other women artists of her time, offered an alternative to the camera as a tool of male gaze. Sophonisbe and Kehna look straight at the camera and break the fourth wall, directly addressing the audience as an act of defiance, taking agency and power over the narrative and the voice that tells it. There is a history of colonial art and film where women do not look ahead, their gaze hidden and fleeing, the coloniser laying his oppressive and reductive gaze onto the indigenous woman, object of conquest. In Fatma 75, the women’s gaze is defiant, daring. They return the camera’s gaze, looking at the viewers, showing us that they are in control of what we gaze upon.

Throughout the jumps between the time periods, from the 3rd century BC to the 7th century AD, and later in the film from the 1930s to the 1970s, the actress continuously speaks in Tunisian Derja, the language of the people, a mix of indigenous Chelha, Arabic and European languages like French and Italian. Derja is a language that is rarely used to tell history, since standardised Arabic is the language entrusted with official knowledge. The choice to put Derja forward announces, then, that this is a film made for a Tunisian audience.

Language can be exclusionary and has historically been used to alienate populations. For a long time, French military archival images were the only ones produced and shown in North Africa, either mutely or in French, as a way to sustain imperial political domination and disempower the oppressed through image and language. However, language can also be a tool to decolonise the screen, ‘an effective means of resistance to mental colonisation and its epistemic violence’. (Rettova 2017)

Standardised Arabic is associated with the Qur’an, as well as with belonging to a larger Arab culture of media and politics, whereas the never-written Derja has to do with private spheres, emotions, feelings, and relationships. (Auffray 2014) Derja enables the move away from both French and standardised Arabic, and the direct access to the national in all of its social classes. (Allal & Geisser 2018) Derja calls to defy the official and controlled; it is self-sufficient, independent, ever-evolving, and closest to popular struggles and movements.

In the film, the voice-over is in standardised Arabic, recalling the language of print, archive and education, contrasting with the Derja spoken within the film itself. As for French, it appears in newspapers and is spoken in the scientific classes, but Baccar makes sure that this is always commented upon in the Arabic voice-over.

The similarity between the voice-over and the actress’s voice blends commentary associated with non-fiction—documentary was at the time mostly associated with TV and PSAs—with fiction-related speech. This way, Salma Baccar builds a stronger manifesto by blending documentary with fiction, not only through visuals, but also through sound.

Embodying the changing and yet continuous feminist struggle, one actress plays both the main character and the reenacted icons of Tunisian history. As the main character, she plays a university student doing research on women in Tunisia. She interviews real figures of Tunisian feminism, and thus embodies the documentary director herself.

Through blending sound from both documentary and fiction and directing a single actress in portraying different characters and interviewing real figures of the feminist movement, the film reveals a struggle for expression, but also a strength of resistance and revolution. The filmmaking then allows for a freedom in structure, a collaborative art form that is on the margin, in common with the feminist struggle.

Beyond the film’s introduction, mirroring the bending of fiction and documentary, linear time is also bent through time jumps between three main time periods: the 1930s, the 1940s up to independence, and from independence to 1975.

We are first thrown into the year 1936 in the Tunisian countryside. On the green mountains, a woman’s voice chants in honour of a dead resistance hero who was killed at the start of the century. A man and a woman work the land together under the oppressive gaze of the coloniser. Never named, they are Tunisians, both subjected by the French. The voice-over speaks of resistance, of women and men working together towards freeing themselves and Tunisia from colonisation: ‘the white scarves intertwined with the men’s capes. They were one word.

The film then cuts to the year 1975, the present moment of Baccar’s film. A young woman looks straight into the camera and introduces herself. She is Fatma, 23 years old. Fatma is played once again by Jalila Baccar, the director drawing a thread between the eponymous character and the iconic women of Tunisian history. Salma Baccar told Stefanie Van de Peer ‘that she called the heroine Fatma as that was the name every Arab woman received from the colonial administration. The title of the film and the name of her heroine count perhaps as a reappropriation of this identity and an assertion that Fatma is not every woman, but an everywoman in Tunisia’. (Van de Peer 2011: 92) We follow Fatma into a classroom where the students discuss the book Our woman in the Shari’a and society by Tahar Haddad. (1930). Fatma has a presentation due on the emancipation of the Tunisian woman and the impact the book has had in Tunisia.

Tahar Haddad’s book considers women’s education essential in both their emancipation and that of the Tunisian people as a whole, advocating for expanded rights for women and a change in the interpretations of Islam, which Haddad claims to have inhibited women. Upon the book’s release, he was immediately denounced by both the colonial authorities and Tunisian conservatives. Starting from his book, which is taught at university and remembered by official history, Salma Baccar uses Fatma’s research as her main motor by which to tell the stories of different women who are neither remembered nor taught about in school.

Fatma 75 is, then, both a film about an essay and an essay film. In a way, as it takes on Fatma’s research structure as its own, it attempts to fill the gaps left in official history. Shots alternate between those of Fatma walking around a library and pages from Haddad’s book. The voice-over analyses the book and quotes from it (for example, ‘Islam grants the same rights to women as it does to men).’ In doing so, this voice-over transforms the written—something accessible only to the educated few—into the oral, which has the potential to be further-reaching. The overlaying of archive with a voice-over speaking in the plural ‘we,’ participates in the reappropriation of academic and official knowledge by and for the collective.

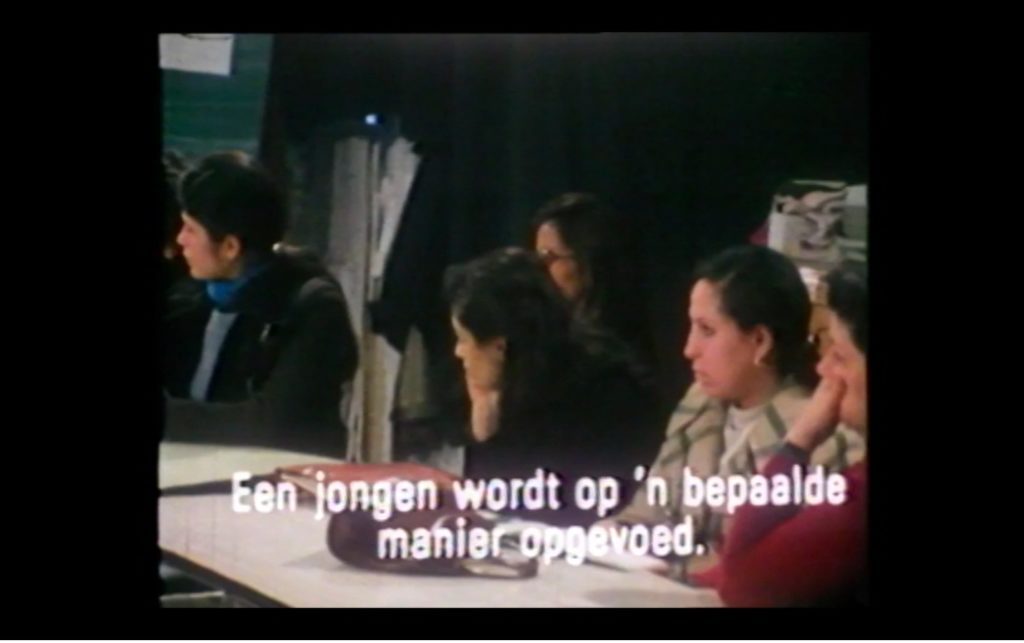

Shifting the set up once again, the woman’s body is discussed for the first time, in a class about human reproduction. In the classroom, female students look on as their male professor teaches them anatomy and reproduction. In French, he tells them that ‘we’—meaning ‘we Tunisians’—raise women and men differently.

The voice-over asks: ‘wouldn’t it be better if they asked these questions to their parents?’ The image immediately cuts to a staged scene of a little girl asking her mom about procreation. Her question is met with a slap and no answer. The fictional scene, shot in a realist aesthetic, serves the strong purpose of visualising the unimaginable. In reality, no one would dare to ask the question. Fiction offers the tools with which to break the taboo.

Back in the classroom a young man asks, ‘Do you think that the Tunisian girl gives a lot of importance to virginity? Still gives importance to virginity?’ The professor answers, ‘We can’t speak of the young Tunisian woman without asking for her opinion.’ Yet the professor does not ask for her opinion. Instead, he moves on with the class. We are left with the young women’s silence.

Fatma’s voice-over then feels all the more essential and free, not only giving the film the weight of a manifesto, but also filling it with context, creating a bridge between the film and people who are not informed or educated.

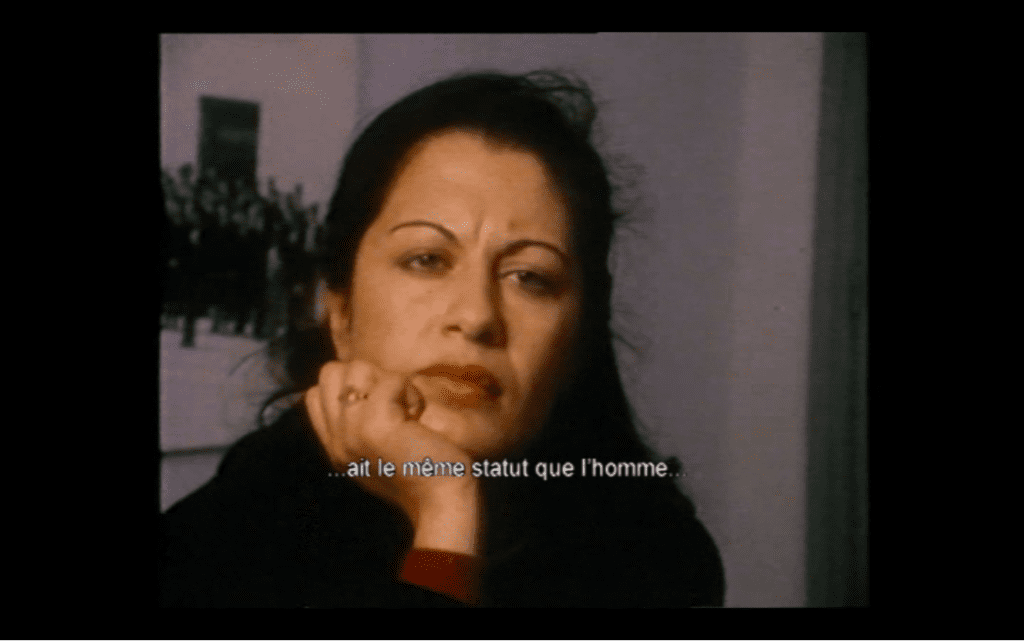

Fatma embodies the voice-over and guides us as she does her research for her presentation. She takes us to a factory, where she discusses gender inequality and the union with the female workers there. A male worker, when asked, says that women work harder but men are paid better. Fatma then talks to the male factory owner, who tries to justify the pay gap. In these scenes, Baccar only grants close-ups to Fatma and never to any man, a way of locating power—the right to speak and to be listened to—in women’s voices. Unfortunately, it seems like the recalling of power stops there, in the hands of Fatma, an educated and privileged young woman who is only at the factory for the sake of her research.

Baccar emphasises Fatma’s feelings of disbelief and anger when hearing these women’s stories. Her face, filmed in a close-up, draws us in as spectators to be Fatma’s accomplices in witnessing the absurdity of the factory boss’s speech. Van de Peer comments in detail on Fatma’s facial expressions and body language: ‘with her head resting on her arm, expressing cynical resignation to the patronising speech, she raises an eyebrow, smiles sarcastically, again raises an eyebrow, and slightly moves the corners of her mouth while she shrugs’. (Van de Peer 2011: 104)

These are the murky waters that both Fatma, as a character, and Baccar, as a filmmaker, navigate: oppressed as women, yet privileged as student, researcher, or artist.

Fatma goes from the factory to talk with Bchira Ben Mrad, founder of the Muslim Women’s Union. Shots of their conversation alternate with scans of archival documents from the start of the Union. A symbol of their own autonomous resistance efforts, the Muslim Women’s Union allowed participants to fight directly within the decolonial struggle. 1956 marked Tunisia’s independence and the establishment of the ‘Code of Personal Status,’ abolishing polygamy, granting women the right to vote, and making girls’ schooling both mandatory and free. (Mhadhbi 2012) The voice-over asks whether society was ready.

This question of whether change should come first from the law or from the people’s ways of thinking, echoes my experience growing up. Morocco gained its independence in 1956—the same year as Tunisia—and immediately passed its first code of women’s rights, the Mudawana. Seemingly advanced for its times, the Mudawana was a way for the government to don a progressive image, all while silencing, keeping control, and setting the context for decades of dictatorship. Amendments were made in 1993 as a way to announce the end of the Years of Lead, and then more change came with a long-awaited revision of the code in 2004. Each time, the Mudawana came with change, but also revealed that feminism could be instrumentalised at key points of a government’s history to rebrand, find a new image, and silence the opposition.

With my experience as a Moroccan woman in mind, I listen to Baccar’s question. It seems to be purposefully open-ended, but to me, although there are always different speeds of change, I believe that our rights can never come too soon.

We come back, one last time, to 1975. The voice-over mentions the plight of those women who have only prostitution as a last option to enable them to survive, as slaves in the ‘Odalisque market.’ The Odalisque, figure of the prostitute/maid, provides a strong closing image for the film. Famously depicted in the 1814 painting ‘La Grande Odalisque’ by Ingres, she is a representation of the fantasised Orient, a symbol of the coloniser’s orientalist and objectifying imaginary. In the orientalist painting, the female gaze is fleeing. Even in their male imaginations, the painters couldn’t picture women looking back. To some extent, unfortunately, the film perpetuates these dynamics, trapped in a way by power struggles that have long been internalised and that exist within struggles of class and patriarchy.

While the voice-over comments that there are other women who ‘hide behind old traditions,’ we follow two women hiding under their veils as they run from the harassing camera. The voice-over then comments, ‘there are other women who won’t change.’ I can’t help but wonder why those women don’t get to speak, why they are only spoken of. Maybe those women did not want to be filmed, or maybe Baccar did not even try to film them. Maybe the voice-over is right, and those women do not want the same as Baccar and her main character Fatma. Although they all experience life in a patriarchal society, there are great gaps of class and privilege between them. There is an inevitably patronising gaze in this part of the film, as it almost seems that Baccar locates the issue of women’s rights as an issue of disagreement amongst women, taking away from the systemic patriarchy at the root of the problem.

Those women flee the camera because the camera has a presence, a movement, and a direction. Image-making and abuse have had intimate ties in colonial spaces, and the camera in public space recalls the memory of the male colonisers and the violence that they and their camera brought onto colonised people—especially onto colonised women. This is part of the weight we carry as filmmakers in postcolonial spaces.

On the other hand, Baccar does try to address the more conservative women, those from rural areas, the ones who did not have access to education or tools of empowerment. Yet the director, who through the voice-over converges with the character of Fatma—educated, privileged, and hence exterior to these marginalised communities—wonders how to talk to women whose lives are out of their hands. The question arises then: who is this film for? Part of me thinks that we will never know. Had the film not been censured, it could have met with rural audiences, maybe even have been used in classrooms in both urban and rural spaces. But maybe upon making the film, Baccar also knew that there was an inherent impossibility in addressing women from different backgrounds.

As a filmmaker, I wonder if taking time to talk with those women, off-camera, to explain what this new camera does differently from the colonial one, to offer the space for their voices, even if they disagree with Baccar’s opinion, would have helped. But then again, perhaps their opinion would have weakened the unity of the manifesto. This is, after all, perhaps a film for the young woman who is already sensitive to the question, who can then use it to confirm and solidify her position, holding it up as a manifesto.

The film ends with Fatma’s presentation. She mentions all the changes in women’s rights that have occurred because of the changes in mentality. She pleads, speaking for the filmmaker, for the change to be allowed to continue. Salma Baccar says that she always fought in her films to express an idea or a thought, leading her to enter a career in politics in 2011, within the Tunisian revolution and upon the ousting of then-president Ben Ali. She says, ‘[m]ost of my films led to scandals, because I was touching upon issues that were still taboo in our society. If I wanted to talk about something, I would’. (Rouxel & Baccar 2016)

By bending time, space, and form, all via a single female actor doubled and tripled through multiple characters and subjectivities, Baccar delivers a timeless decolonising film. Talking about film as ‘social and political interventions,’ she says, ‘for us, image was about reframing the world’. (Rouxel & Baccar 2016) ‘Even when the story doesn’t end well, the female hero in my films still holds on to her goals, to life. Life continues, and women’s destiny will change.’ (Rouxel & Baccar 2016)

REFERENCES

AIM, ‘Africa’s Lost Classics Fatma 75 (1976),’ Africa in Motion Film Festival, https://www2.africa-in-motion.org.uk/africas-lost-classics/exhibition/event/311/ (last accessed 3 September 2020).

Allal, Amin, & Vincent Geisser (2018), Tunisie. Une démocratisation au-dessus de tout soupçon?, Paris : CNRS.

Auffray, Elodie (2014), ‘Le tunisien, l’écrit de la rue,’ Libération, 14 April 2014, https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2014/04/14/le-tunisien-l-ecrit-de-la-rue_997402.

Baccar, Selma (2009), ‘Selma Baccar : femmes à la télévision,’ Tout pour les femmes, August 2009, https://www.toutpourlesfemmes.com/archive/selma-baccar-femmes-la-television (last accessed 30 November 2021).

Mahfoudh, Dorra & Amel Mahfoudh (2014), ‘Mobilisations des femmes et mouvement féministe en Tunisie,’ Nouvelles Questions Féministes, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 14-33.

Mhadhbi, Amira (2012), ‘State Feminism in Tunisia: Reading between the Lines,’ openDemocracy, 7 November 2012, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/state-feminism-in-tunisia-reading-between-lines/ (last accessed 30 November 2021).

Rettová, Alena (2017), ‘Decolonization through Language: The Importance of Language Learning and Teaching for Postcolonial Academia,’ SOAS University of London, May 2017, https://www.soas.ac.uk/cilt/events/10may2017-decolonization-through-language-the-importance-of-language-learning-and-teaching-for-postc.html (last accessed 3 September 2020).

Rouxel, Mathilde & Salma Baccar (2016), ‘Portrait de Salma Baccar, cinéaste et députée tunisienne,’ Les clés du Moyen-Orient, 3 February 2016, https://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Portrait-de-Salma-Baccar-cineaste-et-deputee-tunisienne (last accessed 3 September 2020).

Van de Peer, Stefanie & Selma Baccar (2011), ‘An Encounter with the Doyenne of Tunisian Film,’ The Journal of North African Studies 16, No. 3.

Van de Peer, Stefanie (2011), Negotiating Dissidence, the Pioneering Women of Arab Documentary, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey