‘Talking about me… doesn’t interest me at all’: An Interview with Ana Penyas

by: Isabel Seguí , March 30, 2023

by: Isabel Seguí , March 30, 2023

Ana Penyas (Valencia, Spain, 1987) is a graphic novelist and illustrator. She has numerous publications, including Estamos todas bien (We are all well, 2017), which is about her grandmothers and the generation of women that survived Francoism. The Spanish Government awarded this work with the National Comic Award in 2017. In 2021, she published Todo bajo el sol (Everything under the Sun), a critique of the impact of the capitalist economic model on the territory, and way of living, of the inhabitants of the East coast of the Spanish state, where she is from. Currently, the Valencian Institute of Modern Art is holding a major exhibition by Penyas, with the social researcher Alba Herrero, called En una casa (In a House), that runs until the end of April 2023.

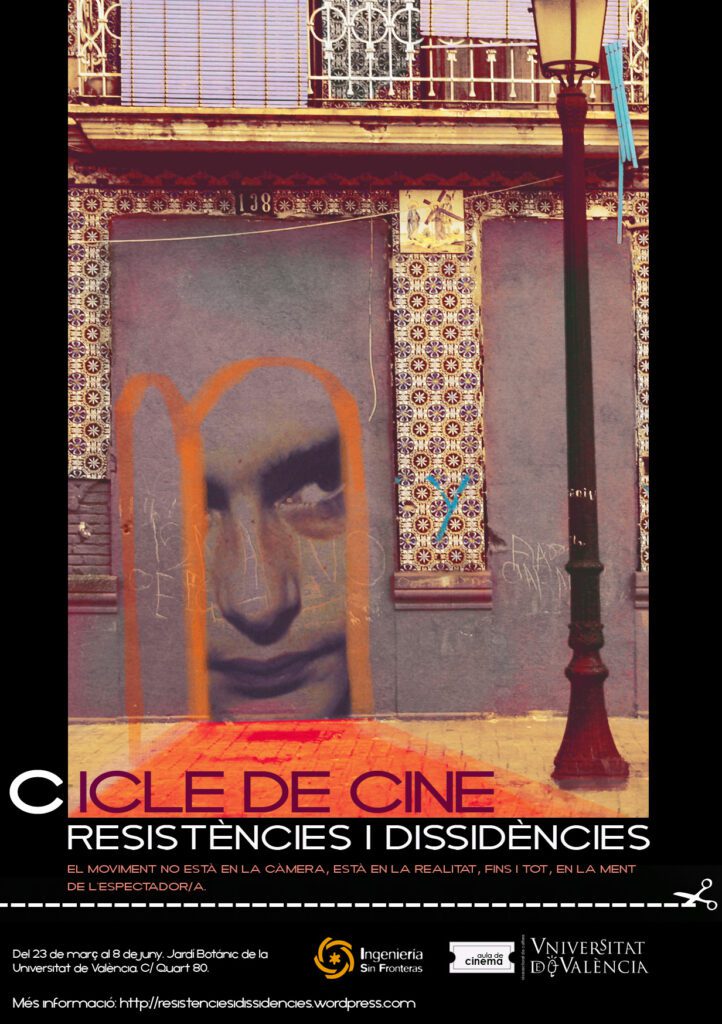

I met Penyas when she was an undergraduate student of Fine Arts. Although she was just starting out, her vocation was clear. She demonstrated the quality of her work and her ability to communicate complex ideas through illustration when she created the poster for a film series we were organising (see fig 1). Since then, I have only seen her grow as an artist and storyteller, able to convey sophisticated social analysis to the general public and generating both visual pleasure and strong emotional responses without relinquishing the radicality of her political stance.

***

Isabel Seguí: Let’s start at the beginning. How do you become a graphic novelist?

Ana Penyas: At first it was an encounter. I was not planning to become a graphic novelist. I wanted to be an illustrator. I started Fine Arts with that clear idea. Before starting my degree, in 2010, I had already taken an illustration course in Barcelona. And there I found my call. When I was finishing my degree in Fine Arts, I took an illustration course. As the final assessment, they made us present a small four-page comic exercise. And suddenly, something happened. It was very organic. The language of comics—perhaps because I used to watch a lot of movies, or I’m interested in photography—seemed to be something that I owned already, almost intuitively. And right there, as a class exercise, I started the story of We are all well. I later enlarged it into an eight-page fanzine and was told by a publisher that the work had potential. He encouraged me to do a graphic novel.

The graphic novel, as a format, was an encounter in my life. And even today, when people ask me, I say that I am an illustrator, but in reality, I think it would make more sense to claim myself as a comic author because that is what I have been doing in recent years. In the field of illustration, I felt safer because it consists of interpreting and giving visual form to texts that are not my own. Instead, the comic format asks for a script and requires a narrative invention. Before, I thought I was not good at storytelling; finding myself comfortable as a narrator has been a learning process based on external recognition.

IS: Within the comic tradition, is there any school or author that has influenced you? What are your references?

AP: When I started, I didn’t come from the world of comics. I wasn’t your typical comic book reader. Until recently, this world was very small and sort of inbred. Comic authors used to be people who had been reading comics all their lives. I was not like that. I had read Mort and Phil as a child, like everyone else. I sporadically consumed graphic novels because I liked them, but I was probably more interested in other fields such as cinema and photography. I started making comics without even having to break the rules because I didn’t know them. I created my own language. But I didn’t intentionally break anything because I wasn’t clear on what I was breaking.

Instead, right now, I’m beginning to have a broader understanding because I’ve been going to comic fairs for a few years now. I have references from Belgium, France, and Germany. Avantgardist authors who play with ugliness, with surrealism. People who already broke everything many years ago, in the 70s and 80s. I could name Anke Feuchtenberger or Brecht Evens as references. I feel close to people who experiment.

The field that inspires me the most, in any case, is photography. I work a lot with collage. And, in fact, when I start a project, I always look for visual references from the photographic medium. I have more photo books than comics. The chosen colour and framing inspire me when starting a project. For example, for Everything under the Sun, I was influenced by the work of photographers like Txema Salvans and Ricardo Cases. I am also interested in documentaries and docu-fiction. My work is a kind of documentary-comic. If I did something audiovisual, it would be nonfiction. But the advantage of the comic is that it allows you to experiment a lot because the means of production are very cheap, and the only investment is the work time you want to dedicate to it. You don’t need expensive equipment or a crew. For my comics, I enjoy the punctual collaboration of many people, but the one sitting down drawing is me.

IS: Apart from visual culture, what other things influence you?

AP: The fields of history, anthropology, politics… I am closer to a militant environment than to an artistic milieu. The tradition from which I come is anarchist, away from political parties and very marked by feminism. I participate in feminist groups in self-managed spaces. For example, when I lived in Madrid, I was in two collectives, Autodefensa Feminista (Feminist Self-Defense) and Carabancheleando (a social research group from the periphery). Now, in Seville, I participate in an assembly called Feminismo de los sures (Feminism of the Souths), conformed by several collectives such as the association of prostitutes of Seville, the Kellys (union of hotel cleaners), and the organisation of women day labourers from the strawberry fields in Huelva. Because of my acquaintances, I land in those spaces when I change cities. And the people in the art world that I interact with are also often quite politicised.

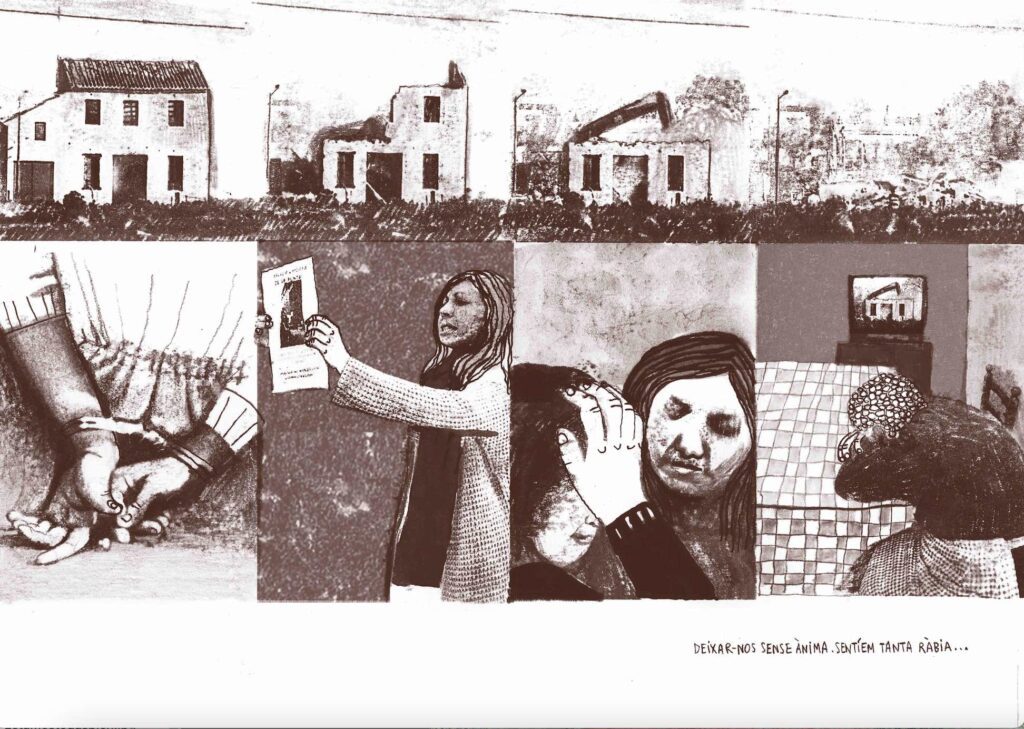

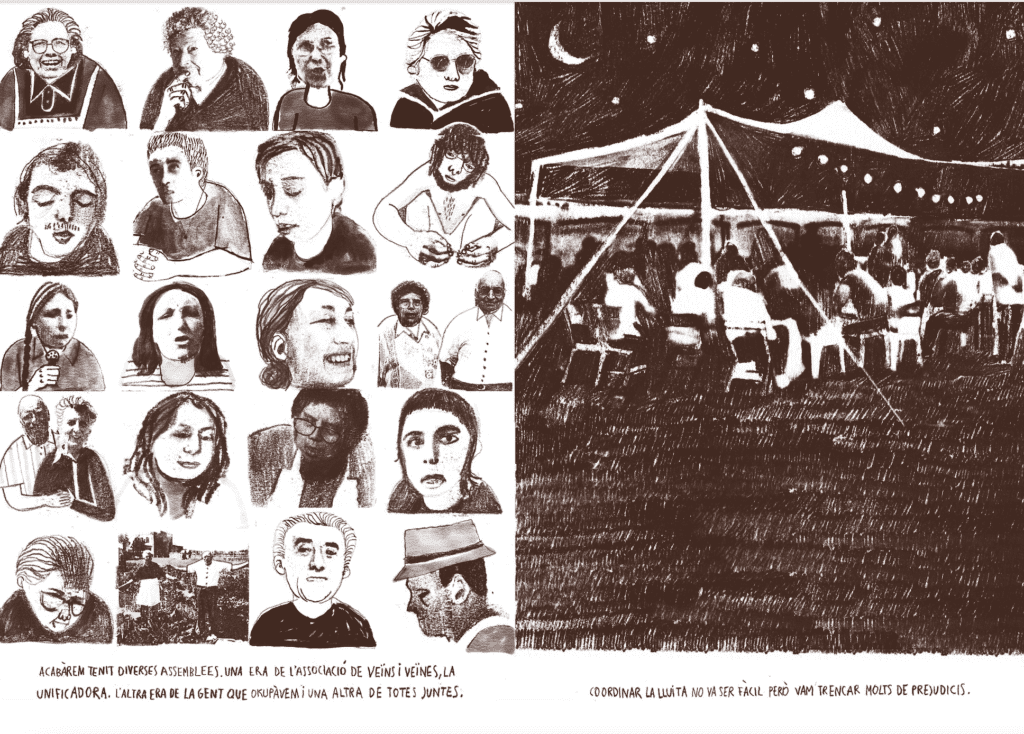

Fig. 2 & 3. Fanzine No van ser tres mesos de lluita, van ser dos anys d’aprenentatge, 2018.

IS: You are a publishing phenomenon in the comic sector, but you are also a militant anarcho-feminist. Do you think that in the Spanish State your political position is understood, and your work adequately contextualized within the Iberian anarchist tradition?

AP: The media does label me a feminist. I think because it is an issue that has been fashionable in recent years. In the interviews I establish what my political position is and where I come from. But, in general, later they do not write it down. I agree that the way the mass media frame my work is often flat. But you know how this country is.

IS: Yes, I know. The reading of your work by the mass media neutralises the historical criticism of the Spanish political and economic system that you make. Let’s talk about the autobiographical as a form of pigeonholing female voices…

AP: Talking about me, about what I am, doesn’t interest me at all. It’s not that I hide it, but I don’t like to feel exposed and even more so today with social networks. I’m scared of it. I don’t want to go into that either politically or emotionally. On the other hand, after the success of We’re all well, which is the story of my grandmothers, what I didn’t want was to be pigeonholed into the subject of biography, micro-stories and so on. I had the need to do something more macro, a structural theme told through characters that have nothing to do with my family; totally invented so as not to label myself. In that sense, I have an excellent editor, Catalina Mejía, from Salamandra Graphic. She told me that she wasn’t going to ask me to make a book about the things that now sell. For example, you get pregnant and make a comic about your pregnancy. She didn’t want me to worry about sales because the success of We are all well, with ten editions and counting, was not going to be repeated. Catalina has encouraged me to consolidate myself as an author with total freedom. In that aspect, I have been very well accompanied.

IS: You have to give credit to the editors. Let’s go back a bit. Your first work was Los días rojos de la memoria (The Red Days of Memory). How did this project come about?

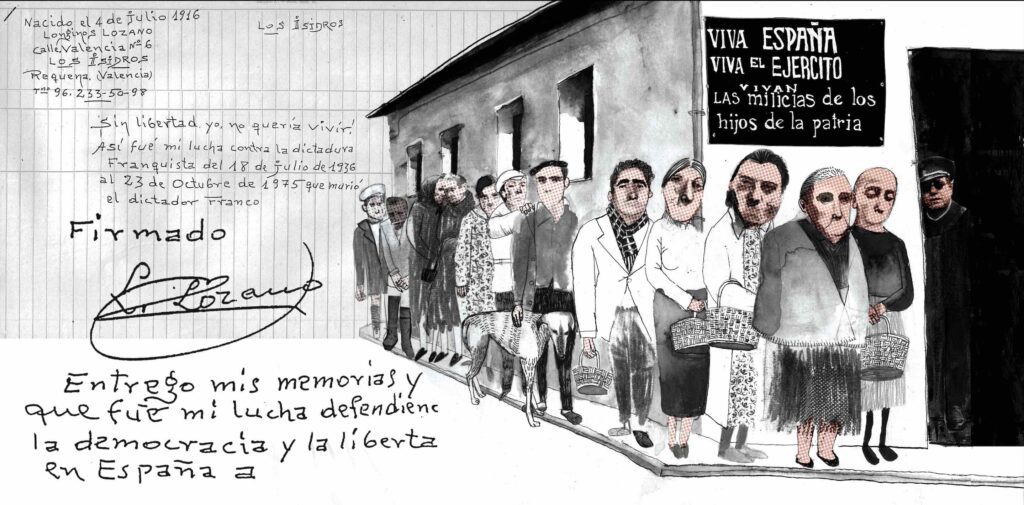

AP: This work was crucial and began in parallel to We are all well. I had to do my final degree project. My friend Álvaro Ibáñez worked in the archive of the town of Requena and told me that he had found Longinos Lozano’s memoirs which, in a few pages and simple language, recount many mechanisms of Franco’s repression. He put together a small interdisciplinary team to interview people from the area and make a book that was to be a mix of memoir, essay and illustration. In the end, the book was not made, but that project was very enriching for me. I submitted the drawings as part of my thesis. Also, in that team, I met two feminist sociologists, Arantxa Alfaro and Isabel Gadea, whose work methodology collecting life stories of older women helped me a lot in the elaboration of We are all well.

Other essential lessons learned from this project, The Red Days of Memory, are the reflections that it allowed me to make on the issue of ‘truth’ in testimonial narratives. Longinos, in his memoirs, wrote that he had been unjustly imprisoned, and his family had been tortured. That was true, but he did not explain something important, that he had acted as a liaison for the maquis (anti-Francoist guerrilla). Also, due to the trauma, he lost his mind. These data made the story of Longinos seem even more compelling to me. I was not interested in having access to ‘the truth.’ He was a very complex character full of fears and contradictions. That complexity interested me more than telling the story of a martyr of Francoism.

The book did not finally come out because the rest of the team considered the story too complicated, but it totally changed my mindset. In fact, We are all well also has to do with that. I wanted to delve into the character of my grandmother Maruja, a woman who did not know how to love. It is not the portrait of a self-sacrificing granny. I am interested in people who are not heroes or heroines. However, their story is not less important for that reason. I was already dealing with the theme of the historical memory of Francoism and feminist methodological approaches. Hence, when I started to embody Longinos, an anonymous person who was telling a half-truth (or the version of his life that he wanted to show the world), suddenly and intuitively, I saw that the history of my grandmothers was very close. Everything was already there: historical memory, life stories of anonymous characters, and a feminist perspective.

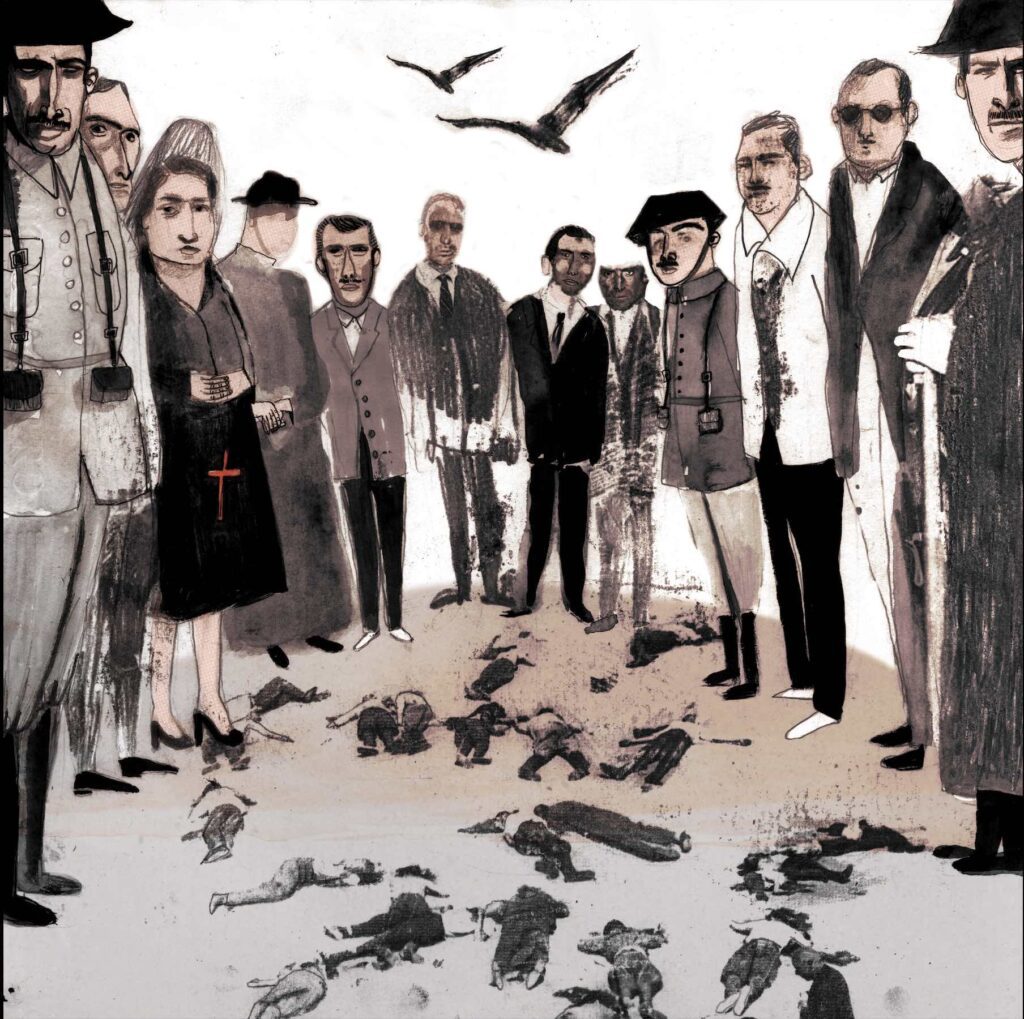

Fig. 4 & 5. Los días rojos de la memoria, 2014.

IS: Much has been written on We are all well. Do you want to explain anything else in this interview?

AP: On a more intimate level, as I have told you, the driving force was my most bitter grandmother, Maruja. I had a wonderful bond with her, but she was the typical machista woman. She was the stereotype of the mother-in-law who crushes her daughters-in-law and is suffocating with her sons. But I wanted to make people understand what happens to a person’s life to become like that. That is the emotional engine of the story. I did not want to sugar-coat my grandmothers or save them. Sometimes I explain this, but I don’t think it is well understood. It is more common that the interviewers opt to enhance aspects such as vindication of care work. But for me, intimately, I was claiming that, even if you are a bloody woman, your story deserves to be told.

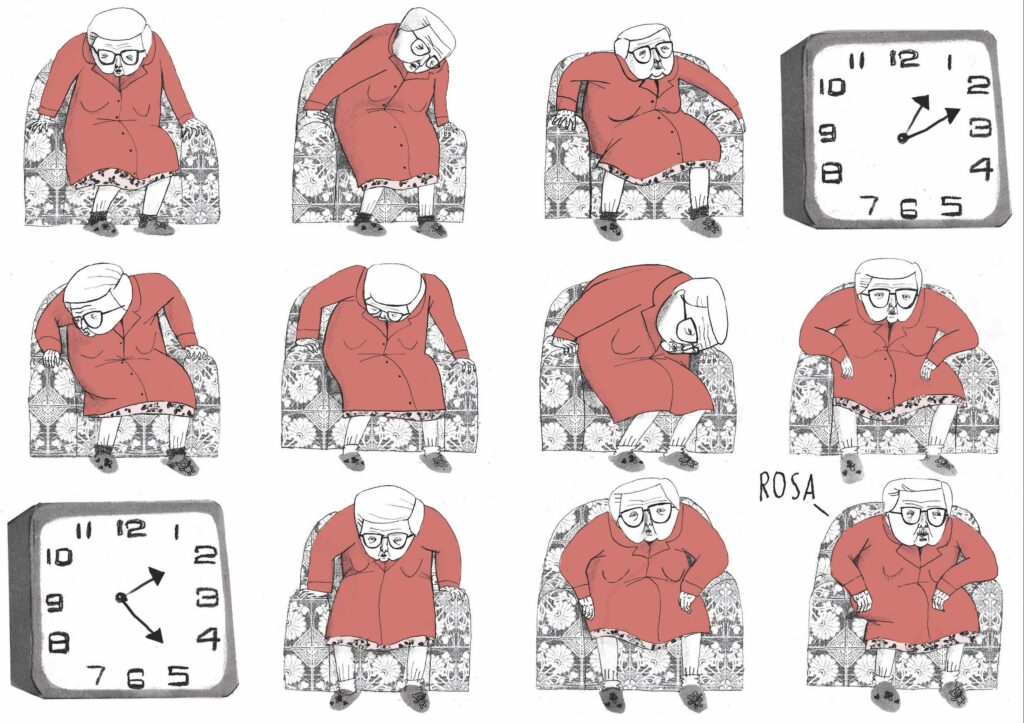

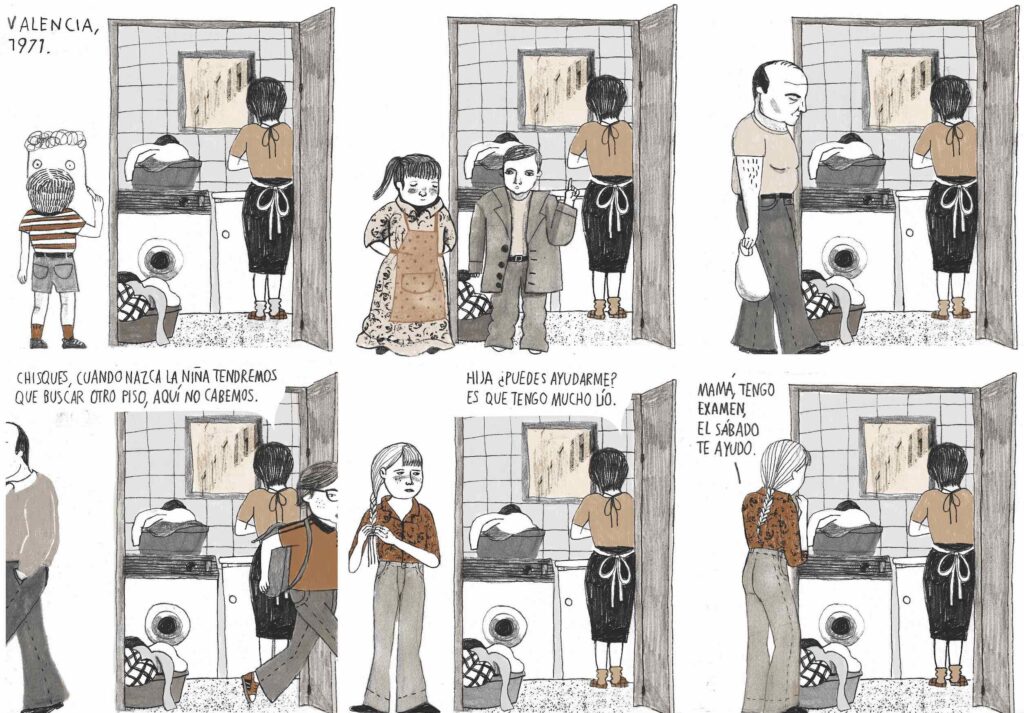

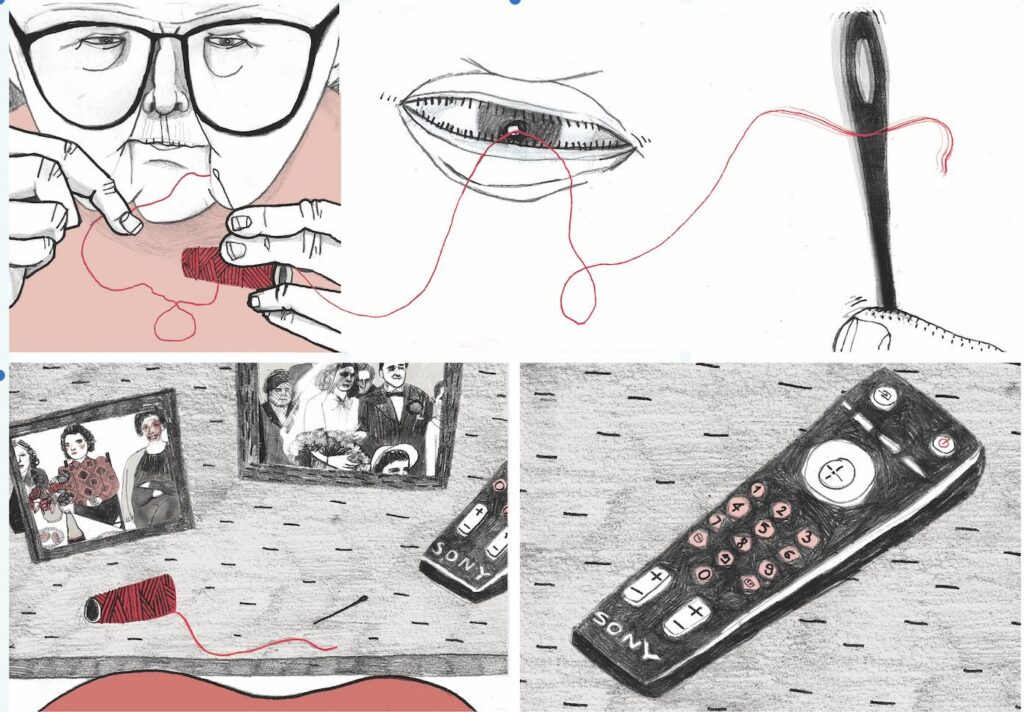

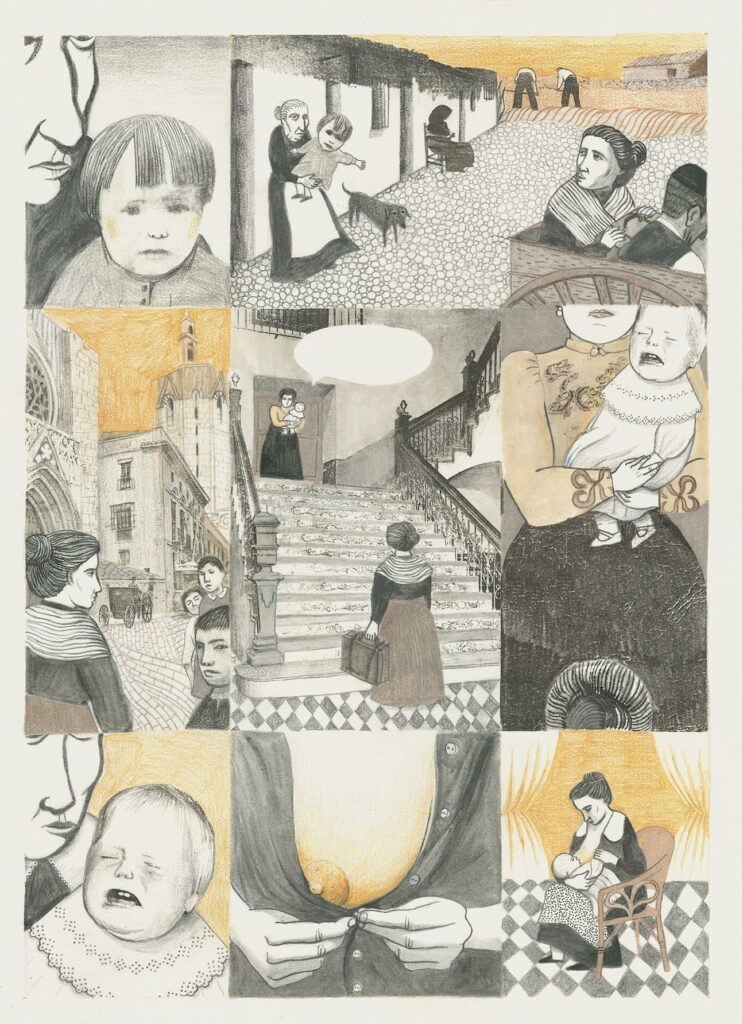

Fig. 6, 7 & 8. Estamos todas bien, 2017.

IS: One of the formal characteristics of We are all well, and of your work in general, is the protagonism of the objects. How do you work the balance between objects and characters?

AP: I go by the maxim of ‘less is more’ even if it doesn’t seem like it (laughs). Nothing is meaningless. If I draw three things on a shelf, they are there for a reason. The critic Álvaro Pons says that, in my work, the background counts the same as the foreground. For the investigation of We are all well, in addition to interviewing my grandmothers, Maruja and Herminia, I reviewed their photo albums and took many pictures of their houses. However, what brought about the idea for the story were the objects because, in the case of Maruja, she had surrounded herself with things that reaffirmed that repressive model of woman. All those figurines and reproductions of paintings that populated her house spoke of a moral and sentimental education that filled the space she inhabited like a mandate. In addition, almost all the anecdotes my grandmothers told me happened in the domestic space, so the objects served me to make time jumps from the present to the past because they were always present.

IS: And Everything under the Sun follows the same logic, but outside, outdoors…

PA: Sure. I was already aware of it. So, if the critic had said that backgrounds count, I was going to give it all! (laughs). In Everything under the Sun, I had to be explicit regarding the passage of time because the story focuses on the economic and political changes affecting the landscape and the territory. Thus, in the images everything changes: the architecture, the billboards, the car models, the businesses, the clothing of the characters, everything speaks about the different epochs. That was a lot of fun at the research level. Also, I made very intense use of colour. The Mediterranean colour range is very bright.

IS: Yes, it appeals straightforwardly to the people who have lived in that time and place. The reproduction, so well researched, of the material life of each era awakens in the readers a precise visual memory of the time, a nostalgia, or rather anguish, in my case (laughs).

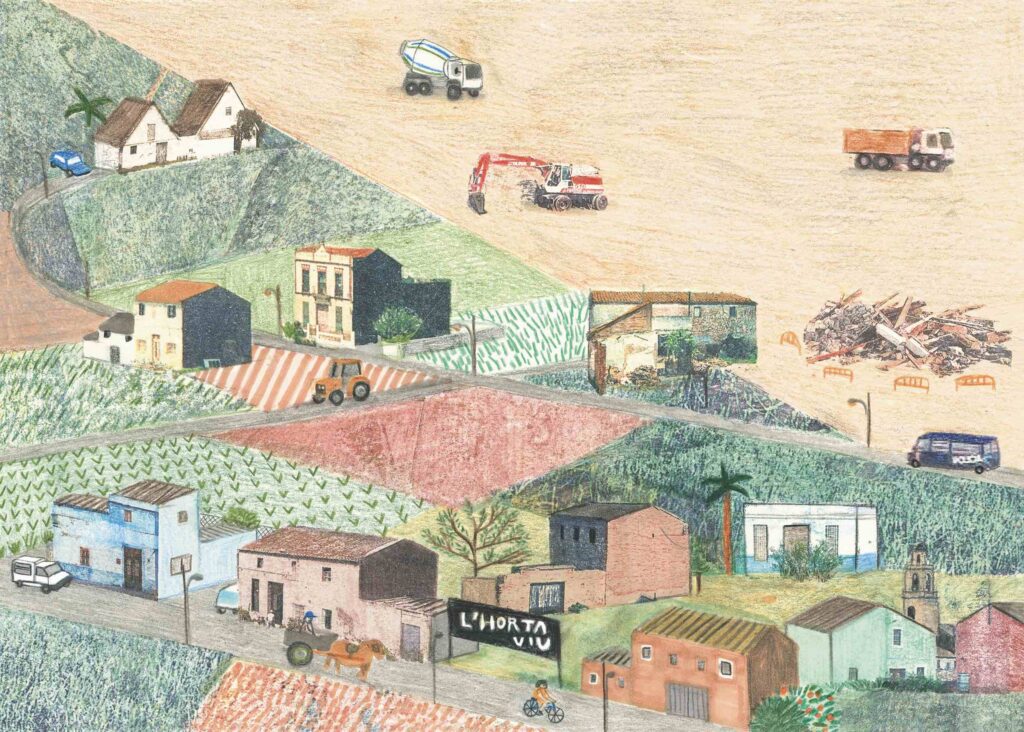

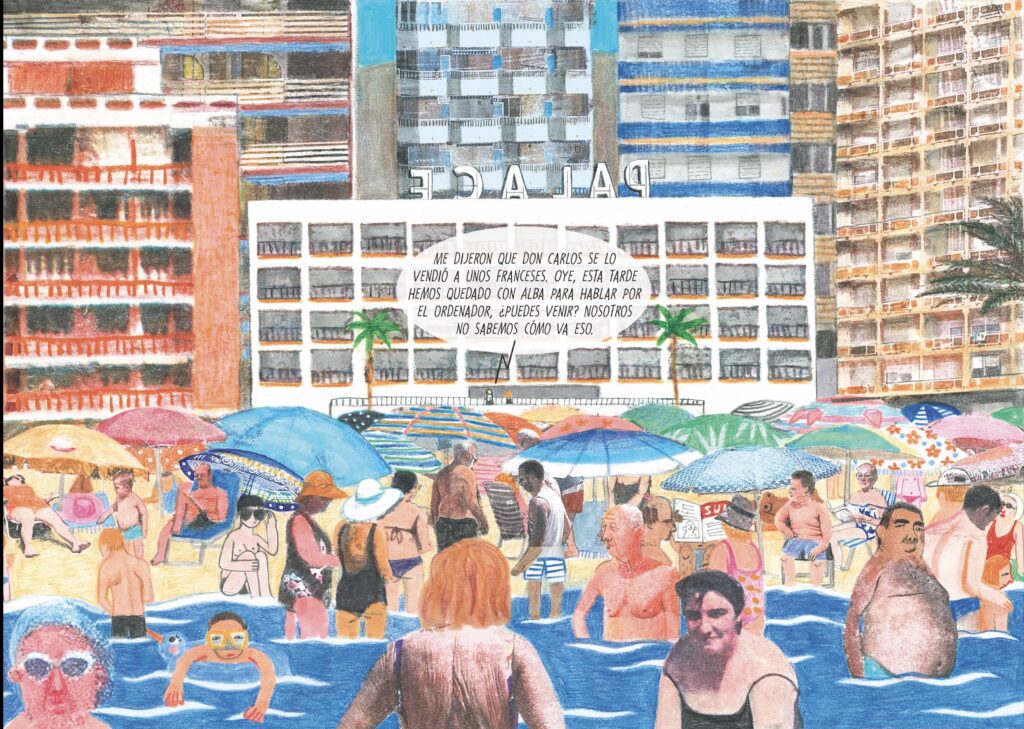

Fig. 9 & 10. Todo bajo el sol, 2021.

IS: Let’s go back to We’re all well, a novel with which you became the first woman to win the National Comic Award in Spain. How was that experience?

AP: For me, the news was that a story about old women had won. A story like that would have been totally invisible not long before. It was not so interesting that I had won but that society’s sensitivity had advanced. On a personal level, it was overwhelming, but I was lucky to have just moved to Madrid and didn’t know many people. I protected myself by indulging in anonymity. Also, at that time, I was doing therapy which also came in handy. In any case, that year everything had gone in crescendo because I had previously won the New Author Award at the Barcelona Comic Fair and another award at the Guadalajara Book Fair (Mexico). Suddenly, I went from having no publications to receiving awards. It was all very fast. But the nerves came later when I had to face the next project, because of the expectations and the fear of other people’s opinions. But the good thing about this job is that you spend most of the time at your drawing table. You are not directly exposed to the public, like musicians do, for example. In addition, the world of comics and illustration is quiet and very little showbiz.

IS: Isn’t the world of comics sexist? From the outside, it looks like it.

AP: It is sexist, just like any other space. Nevertheless, the world of illustration is much less sexist because it is very feminised due to the centrality of children’s literature in it. The men who enter there have a different attitude. The world of comics is more male-centered, it has stars and all the superhero stuff, but it is not a world of big egos. There are not many established critics. It is less pretentious. No one makes a lot of money either. There are some male chauvinists, but it’s a less petty and more relaxed world than other artistic worlds. The year they gave me the National Award, I went to the Black Week in Gijón, and I spent my time with a group of women Spanish comic authors from older generations like Marika Vila, Laura Pérez Vernetti and Antonia Santolaya. They all welcomed me wonderfully. In general, I have felt welcome.

IS: Among your references, you have not named me any Spanish woman comic author. Is that genealogy a bit broken?

AP: Yes, there is a gap. Before, there were very few women. Marika Vila began to do some feminist stories in the eighties in Barcelona. But this is a very precarious world, and life is complicated. She became a mother, published in shorter formats and never made a long story. Times have changed now. Before, there were not so many graphic novelists. But I must also confess that I like other schools like the French or the Belgian more. In Spain, in the beginning, I had as a teacher the Argentine based in Madrid, Jorge González, who is not only an excellent drawer, but I also admired him because of his deep reflection on political issues. In any case, when I won the National Award, I felt intrusive because I didn’t know the genealogy of Spanish comics very well. As I said before, I had read very little.

IS: Let’s talk a bit about your technique. Explain the transfer collage technique that is so characteristic of your work.

AP: I mix drawing with collage by solvent transfer. For the image to be transferred to the paper, you have to scratch it with a pencil. I often transfer only parts of the object or the character and finish the figures by drawing. In the end, you don’t know if it is a photo or a drawing. It’s both. In short, the phases would be, firstly, searching for visual references. Then I make a sketch and put it in Photoshop. There, I add the photos that I have chosen in the investigation. I print that. And I make the transfer onto the paper that is going to be the original. After the transfer, I finish by drawing everything on the original. It’s a back-and-forth process between digital and analogue, but the digital side is often more present during the process, and the final result is analogue. Sometimes, I finish some small details digitally, like adding speech bubbles.

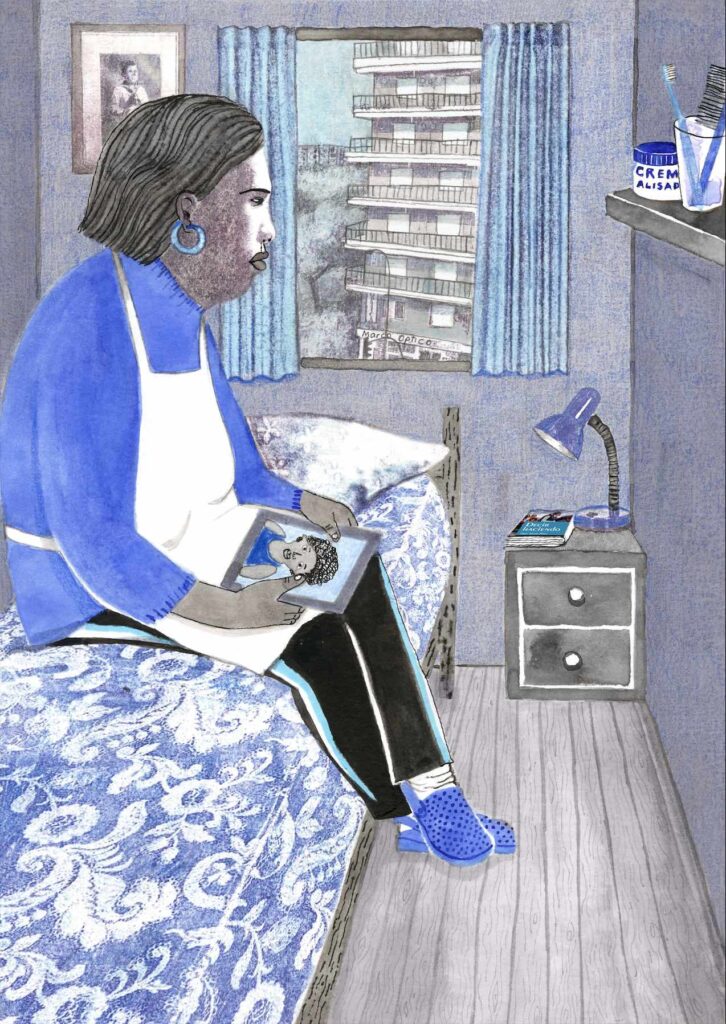

Fig. 11 & 12. En una casa, 2022.

IS: Finally, tell us about your first solo exhibition that can still be visited this month at the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM).

AP: The exhibition In a house: Genealogy of Domestic and Care Work and is a collaboration with the social researcher Alba Herrero based on thirty-five interviews with women domestic and care workers —that is, people employed in other people’s homes— from different generations, from the post-civil war period to the present. We have also interviewed middle and upper-class women employers. Men are not present in the exhibition because their contribution was not relevant.

Based on the interviews, I have made about forty drawings that go by era but with more emphasis on contemporary representations. Sometimes they are composed using different life stories. We also did workshop sessions with a group of domestic workers. The result is a fanzine that is part of the exhibition too. Other essential elements, such as archival and audiovisual material, are on display, and the audios of the testimonies corresponding to the drawings are available to be heard with headphones while you look at the images.

IS: I’m going to Valencia in a couple of weeks to see the exhibition before it finishes. I am looking forward to it. Thanks, Ana!

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey