Tactics and Praxis: A Manifesto

by: Isabelle McNeill , Louise Haywood & Georgina Evans , January 27, 2020

by: Isabelle McNeill , Louise Haywood & Georgina Evans , January 27, 2020

As women and as academics we have found ourselves increasingly troubled by two things. Firstly, where is the time for our creativity, pleasure, exploration, discovery and curiosity? Secondly, in the midst of relentless pressure, how to respond to political and environmental crisis? Where is the connective tissue for collectivity? How can activism happen while working for institutions entrenched in multiple forms of privilege? Is it possible to use what power is accorded to us within such a system to stand with and work for those who have less?

We believe these two aspects are fundamentally linked, that our stress, our anxiety, our dissatisfaction, and even our depression, are political. This has been argued, compellingly, by scholars such as Ann Cvetkovich, who in her book Depression: A Public Feeling proposes that we consider personal mental health in the light of ‘histories of colonialism, genocide, slavery, legal exclusion and everyday segregation’. (2012: 115) She argues:

The intimate rituals of daily life, where depression is embedded, need to be understood as a public arena, or alternatively as a semi-public sphere, that is, a location that doesn’t always announce itself or get recognized as public but which nonetheless functions as such. (2012: 156)

Cvetkovich also suggests that creative practice might offer one path towards collective and individual healing. She sees this not as a ‘magic bullet’ but rather as part of ‘the slow, steady work of resilient survival, utopian dreaming, and other affective tools for transformation’. (2012: 2) We, the three authors of this manifesto, engage in a range of creative activities outside of our academic lives, and Cvetkovich’s words resonate with us. Yet, we have found it difficult to reconcile these activities (and ideas and feelings) with our experience of research and teaching.

In this manifesto, we propose that bringing creative praxis into institutional space enables us to rethink academic labour. We turn to tactics as feminist pedagogy (in the most inclusive sense of feminism and pedagogy) in order to create spaces and practices that work against the patriarchal, neoliberal structures of power that shape academic life and teaching.

Interlude: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s A Dialogue on Love

Writing, my perfectionism gets all over everything. I wrestle and contort to keep it at bay long enough for words to get onto the screen. Like Michelangelo knowing what’s supposed to emerge from the marble block, my task is to excise everything that isn’t that. Maybe it’s called ‘knowing what you’re doing’; it feels less and less good.

But in this other, indiscriminate realm, that conscience has no foothold. What am I doing? Mess with ‘stuff’. Having materials in my hands; seeing, at an instant of pause and speculation, whether there’s something satisfying, something surprising to me, that they almost are.

Little to ask! When

they turn into anything

(lovely) – I’m in joy. (Kosofsky Sedgwick 1999: 199)

The Context

When our Faculty, the Faculty of Modern & Medieval Languages and Linguistics at the University of Cambridge sent out a call for seminar funding applications, we decided to use this opportunity to set up a series of seminars that would explore the intersection between academic work and creative practice, challenging the boundaries normally operating between theory and praxis, as well as between institutional and intimate experience. These gatherings would create a space for aspects of our work and experience that were normally supposed to be excluded from the professional sphere of the university.

Our starting point is our experience as three women academics (teachers and researchers) finding that academia is fully permeated by the contemporary ‘achievement era’ (Han 2015), in which the disciplinary negativity of ‘should’ has morphed into the excessive positivity of ‘can’: ‘Prohibitions, commandments, and the law are replaced by projects, initiatives, and motivation’. (Han 2015: 9) As neoliberal subjects, we are expected to work on ourselves, rather than on collective, social change. In teaching, this leads to ‘a place where education has been undermined by teachers and students alike who seek to use it as a platform for opportunistic concerns rather than as a place to learn’. (hooks 1994: 12) For feminism, this can mean—as Sarah Banet-Weiser has pointed out—the visible display of ‘I’m with her’ rather than the political actions of ‘we’re with each other’. (2018: 184) It is helpful to understand this neoliberal kind of self-work in terms of what De Certeau calls strategies, as opposed to tactics: ‘every “strategic” rationalization seeks first of all to distinguish its “own” place, that is, the place of its own power and will, from an “environment”’. (1984: 36) Institutions too are strategic places that demarcate spaces and accumulate gains in the form of grant funding, prizes, star ratings etc. In their current form, they are, therefore, ill-placed to foster solidarity, transgression from norms and creativity; they are not conducive to feminist pedagogy.

Tactics, on the other hand, have no ‘proper’ place and must ‘seize on the wing the possibilities that offer themselves at any given moment’. (De Certeau 1984: 37) De Certeau found in popular, working-class culture a model called la perruque: tactics for diverting institutional time and resources and using them against the grain of the system. (1984: 24) He explains:

The worker who indulges in la perruque actually diverts time (not goods, since he uses only scraps) from the factory for work that is free, creative, and precisely not directed toward profit. In the very place where the machine he must serve reigns supreme, he cunningly takes pleasure in finding a way to create gratuitous products whose sole purpose is to signify his own capabilities through his work and to confirm his solidarity with other workers or his family through spending his time in this way. With the complicity of other workers (who thus defeat the competition the factory tries to install among them), he succeeds in “putting one over” on the established order on its home ground. (1984: 25-6)

For De Certeau such tactics are not a game—though they may be playful—but rather a way of countering institutional strategies that stifle creativity and solidarity. Applied in academia, diversionary tactics would lead to ‘a return of the ethical, of pleasure and of invention within the scientific institution’. (1984: 28) We believe that such tactics can contribute to the ‘utopian dreaming’ and ‘affective tools for transformation’ invoked by Cvetkovich. We use institutional spaces and funding to bring people into contact with each other and with ways of being and doing that can feel impossible in our ordinary working lives.

Aims

This seminar series has become a project or even a movement—or, perhaps more accurately, a wave that is sweeping us along and bringing other people into the current—that was not planned or calculated in advance. We are working thoughtfully and collaboratively, and we are inspired by the hard intellectual and activist work of fellow spirits both past and present. But we are making it up as we go along, making mistakes and continually learning—essential components of pedagogy, especially when understood through Bernice Fisher’s idea of education ‘taking place in the process of action’, rather than as a product to be possessed. (1981: 21) Writing this manifesto is a first step towards taking stock and setting down what we are learning. From the outset, however, we have been working with the following aims:

- To challenge the neoliberal emphasis on ‘outputs’, which understands academic work in terms of product and productivity and reinforces patriarchal and hegemonic power systems.

- To question the institutionalisation of academic writing and publishing and its imbrication in structural inequities and hegemonic ways of thinking.

- To foster solidarity and alternative, collaborative networks. We also value the individual for their presence and their contribution as a fully equal member of the community.

- To valorise affect and the body in teaching and research contexts and to open the possibility of channels of communication between ‘professional’ life and intimate experience. We support, recognise and acknowledge affective and embodied responses and connections between individuals in a community context where these occur and challenge the silencing of such connections and experiences.

- To site creativity at the centre of academic life, including creative practice that does not always easily or obviously relate to our teaching and research expertise. We understand all kinds of creative practice not only as an antidote and resistance to the demands of working life but also as offering new ways of thinking and acting, ethically, politically and intellectually.

We explore these aims further through the following sections, each of which considers the above ideas in relation to the seminars we held in 2018-19, with Kathryn Rudy, Katherine Angel, Shreepali Patel, Catherine Grant, Emma Cayley, Afrodita Nikolova, Leila Mukhida and Jane Partner.

Resisting the Productivity Model

Everyone is busy. It has become important to be seen to be busy to the point of breakdown in university life. If you are not, it means you are shirking. Conversations over lunch or at conferences can descend into competitive martyrdom. Overwork is also a fact of life, as Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber point out in their important book The Slow Professor: ‘the very idealism that drives intellectual and pedagogic endeavours is easily manipulated by the university … the more committed we are to our vocation, the more likely it is that we will experience time stress and burnout’. (2016: 16) Between being over-committed and needing to perform this excessive working, where is the time to go slow, to reflect, to resist the prevalent model of education conceived in purely economic terms, with students as consumers and teachers and researchers as producers of ‘outputs’?

This is also a feminist problem. Whether or not we are parents or carers (and all three of us are), the tasks of nurture and emotional labour often fall predominantly to women, and such work tends to remain obscured and undervalued, compared to the prized ‘outputs’ we are pressured to churn out. Not enough has changed since Adrienne Rich wrote:

It is difficult to imagine, unless one has lived it, the personal division, endless improvising, and creative and intellectual holding back that for most women accompany the attempt to combine the emotional and physical demands of parenthood and the challenges of work. To assume one can naturally combine these has been a male privilege everywhere in the world. (1979: 147)

We attended an open meeting in our institution to hear the findings of a large research study on the impact of caring roles (not only parenthood) on career progression and research. At the meeting, a woman whose job it is to promote diversity and equality in the university stood up and described a scheme run by the institution that offers financial support to help carers return to work by, for example, providing funds for children and partners to travel to conferences etc. For several of us present, it was a bitter moment: because the scheme was only open to those employed in the most narrowly defined terms by the university (i.e. not including those in temporary posts or those employed by any of the University of Cambridge’s thirty one Colleges), we were not eligible to apply, and nor would be any member of the vast cohort of teachers and researchers who conduct much of the university’s daily labour on a casualised basis. This is far from unique to Cambridge. Across higher education in the UK and elsewhere, huge numbers of teachers and researchers without secure contracts cannot even hope to benefit from institutional measures which claim to be motivated by a vision of equality. Even when eligible, such schemes can end up contributing to the institution’s gradual encroachment into, and colonisation of, a private or personal life led outside of its boundaries. They effectively steal bits of the lives of the person or people you care for and put them to the service of the institution, whilst taking on the appearance of supporting the careers of those eligible. This pattern is widely replicated, and one need only read Rebecca Harrison’s critique of Athena SWAN (2018b) to see how glossy schemes which purport to make things better continue to place disproportionate burdens on those already working at a disadvantage, while simultaneously refusing to address urgent questions about who is being excluded from the conversation altogether. Where the productivity model prevails, this will not improve: structural transformation is needed.

Berg and Seeber approach this by thinking about time. They survey some of the advice literature for academics that promotes ‘time management’ and conclude that ‘these models of time management and productivity strike us as unrealistic and simply not sustainable over the long haul for most people’. (2016: 20-21) They propose a ‘counterculture, a slow culture, that values balance and that dares to be sceptical of the professions of productivity’. (2016: 21) Timelessness must counter time management.

Living in a constant state of guilt and self-reproach, as many colleagues do, is not beneficial for our students. Indeed it precludes feminist pedagogy. When we attend meetings about student welfare we hear time and again the consternation from those around the table: why are our students so stressed? Why is their mental health so poor? Surely we just need to look around at each other to find the answer. At its negative extreme, wry observations about the snowflake generation fall from the lips of those most invested in the culture of self-martyrdom, shoring themselves up in the display of productiveness and efficiency; after all, they mutter, it never did us any harm, did it?

Michelle Boulous-Walker has argued for the importance of slowness for philosophical thought, proposing that a slow and meditative form of attention, or ‘reading’, is vital for a kind of thinking that has ethics and creativity at its heart. Reading that is abstract, formal or disengaged, ‘fails to return us to the world’. (2011: 272) On the other hand, slow philosophy encourages ‘anxiety-free exploration’. (2011: 275) It ‘opens the space of reading to ethics by providing the leisure and time to engage; the opportunity to question and to continue to question in the midst of an age of “work”’. (2011: 275)

Our sessions offer an opportunity to slow down in a communal space and moment of mutual recognition, even for a brief while, and to encourage each other to value fallow time which may appear to be wasted or unproductive. This also means opening up to unforeseen outcomes rather than producing outputs. For her session in January 2019, Catherine Grant suggested—among other things—that we read Marion Milner’s On Not Being Able to Paint (2010). Milner analyses her experience of trying to learn to paint and compares it to her practice of ‘free drawings’, or doodles. The latter illuminates how we engage with and incorporate or distance ourselves from objects in the world. In the process of her investigation she concludes that the creative process does not work from purpose to deed (2010: 169), but rather flows from ‘vague uneasy feelings and an urge to follow certain trickles of curiosity wherever they might lead’. (2010: 169) Through a ‘lived’ experience of experimenting, drawing, and thinking—a form of slow philosophy, perhaps—she comes to the belief that ‘new things are not produced by an omnipotent command from above’ but rather ‘by a free interplay of differences with equal rights to be different’. (2010: 170) Milner’s work shows that resisting the productivity model is not only about ‘slowing down’ but also about freeing up. When we remain focused on producing ‘outputs’, just taking more time to manufacture them might not be enough. Sometimes, plunging in and making, doing or writing quickly—using speed to unfold into the flow and counter inhibitions, fears, judgement—might open up the ‘anxiety-free exploration’ that Boulous-Walker proposes. Timelessness is not only about ‘slow’ or ‘fast’ but about radically rethinking our relationship to time. Our sessions have allowed us to experience this through practical activities such as doll painting or ‘river journeys’ (more in Section 5 below): new and rapidly executed tasks, which shifted our focus away from economic conventions of a ‘valuable’ product and onto process and discovery.

Rethinking Academic Writing

Academic writing has become stagnant in part because it is expected to perform exactly the masterful ‘command from above’ that Milner identifies as a barrier to new ideas and forms. From the abstract, grant proposal or book proposal onwards, each project must appear to be shaped in advance. Once written, the introduction already anticipates the conclusion in a coherent and stable structure. In her conclusion, Milner exposes the myth of her introduction’s mastery: ‘[t]he habit of thinking in terms of purpose to deed was still so strong that when writing the Introduction, after the book was nearly finished, I almost believed that it was a true statement of how this investigation had begun’. (2010: 169) Many academic writers, we feel sure, will feel a rush of recognition here: we know this is how we work, that thinking happens through process, through writing. It is rarely a question of simply ‘writing-up’, particularly in the Arts and Humanities and in qualitative Social Sciences.

In our seminars, we found ourselves returning often to the idea of ‘covering up’ or ‘covering our tracks’: the paths travelled to produce ‘outputs’ must be meticulously effaced in the final product. This includes all aspects of the creative process, such as the often strange, personal reasons we are drawn to particular topics, as well as the circuitous, emotionally complex labour involved in reaching our tentative conclusions and shaping them into text. As Harrison has written poignantly of what she calls the ‘Brilliant, Creative Woman’: ‘All her projects are polished until they shine so that no one guesses at all the crying, the sweating, the bruising, the difficulty sleeping that she pricked and stuffed and thrust into her brilliant work’. (2018a) Tellingly, the all-too-recognisable narrative that Harrison unfolds of the Brilliant, Creative Woman is one where she is perpetually, ‘standing toward the back of the stage, in the shadow of the man that undermined her, assaulted her, or manipulated her’. (2018a)

The nature of academic writing was a current along which discussion flowed in Katherine Angel’s seminar. Her first book, Unmastered: A Book on Desire, Most Difficult to Tell, had roots in her doctoral research in the history of psychiatry and sexuality. In the seminar, she described her experiments in voice and exposure, the entanglement of form and content, and confronting the very real danger which could arise from writing and speaking, publicly and personally, about desire, as a woman. After publication, many told her of her ‘bravery’. She did not feel brave, but did sometimes fear how a certain kind of man might react, whether she would be seen to be ‘asking for it’. It was also a bold step not to choose a conventional monograph as the ‘output’ from her doctoral thesis. In the seminar, we considered creative writing as a potential alternative to the rigidity of academic discourse and its conformism. Angel also writes in more traditional academic modes; we do not reject these. We are aware, however, that, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick has shown, ‘peer review has its deep origins in state censorship … and … was intended to augment the authority of a journal’s editor rather than assure the quality of a journal’s products’. (2009: 11) Such origins hover in the background of the contemporary review process, which often tends to emphasise authority—whether of the individual scholar or the journal (which might be rated according to its prestige). Rosalind Gill has pondered why review seems so prone to degenerate into hostility and concludes that it ‘is produced by the peculiarly toxic conditions of neoliberal academia’: repressed rage emerges in a desperate bid for mastery. (2010: 239) Unmastered destabilises academic writing, the idea of the masterful writer and also unmasters us as readers too. It shows how writing might be, as Kathleen Stewart puts it, ‘like catching your breath. A time-out scanning the surface of what’s going on for a place to begin. Words touch bodies and things, light on what might unfold, nudge a line of composition for good or for bad’. (2018: 188)

VII.3. I love this thing in here.

I shudder and laugh; this phrase delights me.

My laughter amuses him. We laugh a lot: in bed, in the kitchen, on the phone. His laugh is a deep staccato, almost spoken. I feel it in my belly. It triggers mine; that triggers his. Before long, we are a festival of laughter.

VII.4. He knows I am writing about sex. On the phone, on a day when I am at a desk in London and he is by a fire somewhere, I tell him I have written a lot today. He says, You know, I have just now put these things together: you and I have sex, and you are writing about sex. He laughs— wide open laugh. (Angel 2014: 64‑65)

Is this academic writing? Is it memoir? Is it fiction? Is it literary? Non-academic? Was it peer-reviewed? Who is a peer? Is it peer-less? Peerless? What is its value? How is it valued? Is it valueless? Why are the sections numbered? Why, oh why, are there so many blank spaces and pages? Is that writing?

Is it informed by a deep and in-depth grasp of the subject? Who judges?

Subject? Topic? Matter? Substance?

Subject? Her? How can she write about sex, her sexual desire and intimacy? What gives her the right?

Subject? Him?

He wants his own words.

He has his own words. (Angel 2014: 65)

Subject? Me? How does it make me feel? Am I a voyeur? Am I curious? Am I envious? Am I aroused? Does it give me pleasure? Am I angry? Am I outraged? Do I recognise myself? Is this my desire? Do I judge? By what measure? Who?

Subject? We?

I.8 We are women whose bodies can only rage—rage with desire—in response to this sanitized hyperreal. (Angel 2014: 220)

Fresh ways of approaching academic and intellectual enquiry also became the subject of Catherine Grant’s session when she told us how she, a film studies scholar, had come to work with video and her particular approach to video work. It began with writer’s block and became an entirely new way of working, ‘not only learning to love your unconscious but letting it flower and bloom’. It was a period during which Catherine was lucky enough to be able to take a few years away from a full time academic post that created space for this flourishing. Rather than a conventional output, her immersive reading during that time led to the creation of Film Studies for Free, described on the site as a ‘pluralist, pro bono, and purely positive web-archive of examples of, links to, and comment on, online, Open Access, film and audiovisual media studies resources of note’.

Catherine also began experimenting with video, seeing it in terms of the ‘humming’ that Claire Pajaczkowska (2007) found in Milner’s work (an acoustic counterpart to doodling). Catherine described her praxis as an embodied, unknowing play that opens up within a ‘framed gap’, or regular constraint of time and space, ‘within which something may be found that is not available for encounter anywhere else’. (2007: 47) A blank piece of paper, the timeline in video editing software, as much as the analytic session or daily journaling practice may all constitute a ‘framed gap’ to enable such play to take place. In Catherine’s own practice, this involves working or playing with found materials, altering and juxtaposing sequences of films to allow new connections and ideas to emerge. Within this ‘material unthinking and unknowing’, aspects of synchronicity and coalescence take shape in the framed gap of the timeline. The Haunting of the Headless Woman (2019) is a powerful example of an argument that is recognisably academic, bringing a new understanding of Lucrecia Martel’s 2008 film The Headless Woman, but which took shape through various experiments and reworking, in form and length, and through projections in different settings. The final observation, Catherine told us, ‘came at the moment of finishing the work’. Catherine continues to write academically about film, often in the form of a reflection on her own videos, but this comes at the end of a process that rejects traditional models of research, publication and singular authority, in favour of a relinquishing of full control and ownership and a recognition of the porous boundaries between the inside and outside of the self.

Fitzpatrick argues for a shift in the way we think about academic writing in the digital and social media era. Beyond collaborative authorship, she argues that collaboration is and should be at the heart of all academic writing: ‘what we will need to let go of is not what we have come to understand as the individual voice, but instead the illusion that such a voice is ever fully alone’. (Fitzpatrick 2009: 8) Such collaboration might take on the form of post-publication rather than pre-publication review, as exemplified by the publication process of Fitzpatrick’s own book and in initiatives such as MediArXiv, a community-led, digital archive for media, film and communication research founded by Catherine Grant and others.[1] Certainly we may want to preserve, as Michael Bérubé argues, the ‘fragile’ yet protective aspects of ‘protocols of scholarly communication’ that peer review offers in the age of social media storms and the ‘swell of online outrage’ which can also act as censorship. (2018: 137) It is a question of thinking carefully and radically about what to jettison and what to keep.

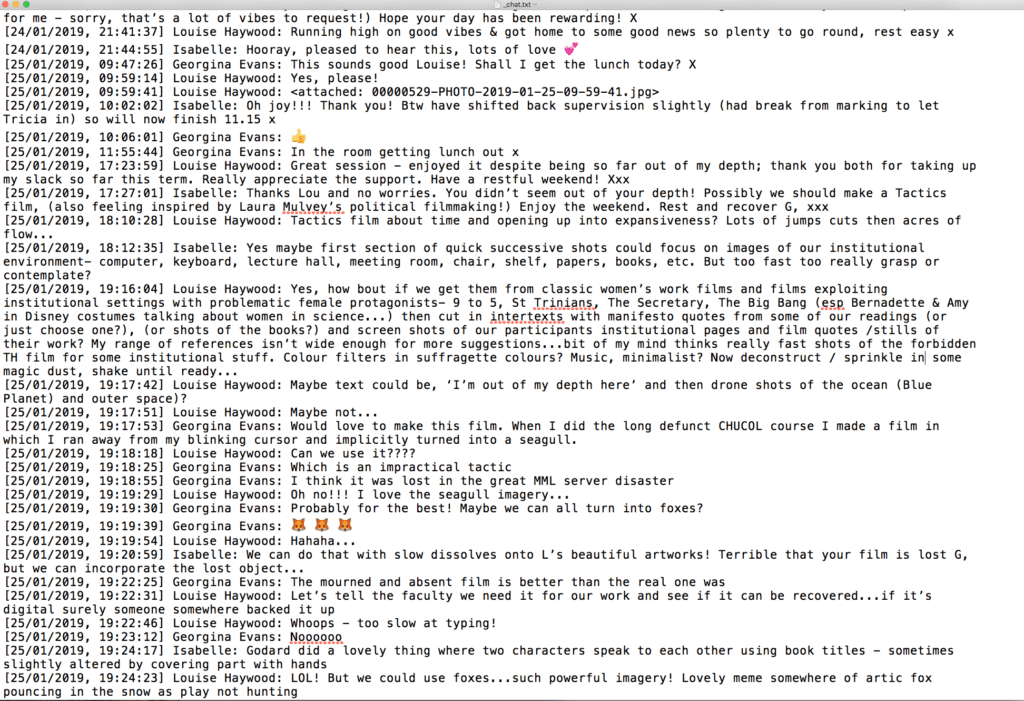

In terms of feminist pedagogy, our collaborative work for and through the seminars has revealed the hugely generative and creative potential of collaborative intellectual thinking and labour, which in our current institutional structures are both invisible and discouraged. (Fig. 1) To return to Stewart, ‘[w]riting now, we might find ourselves caught up in something we’re composing, like music or a conversation that’s taken hold’. (2018: 188)

Fig. 1 Tactics Group WhatsApp Messages, January 2019.

Solidarity & Shared Pleasure

In each event we organise, we aspire to create an inclusive and supportive space. We acknowledge the limits of what individuals can manage, resisting the potentially limitless demands of institutional working lives, in addition to home lives. As Philip Mirowski has argued, ‘The summum bonum of modern agency is to present oneself as eminently flexible in any and all respects’ (2014: 108), a pressure that underpins the exploitation inherent in the ‘gig economy’. Such exploitation particularly affects those in precarious employment— as common in the casualised workforce of academia as everywhere else.

With such limits in mind, our sessions take place at lunchtime to minimise conflicts with childcare arrangements. In addition, we are acutely aware that participants’ timetables are overfull, so we encourage people to drop in as and when they can, without censure for arriving late or leaving early. In collaboration with our speakers, we share reading and/or viewing material in advance of each session in order to stimulate exchange and discussion. However, we know all too well that it can be difficult to find time to prepare: to this end we always offer a brief presentation of the readings or viewings for the session, so that no-one feels excluded from the discussion.

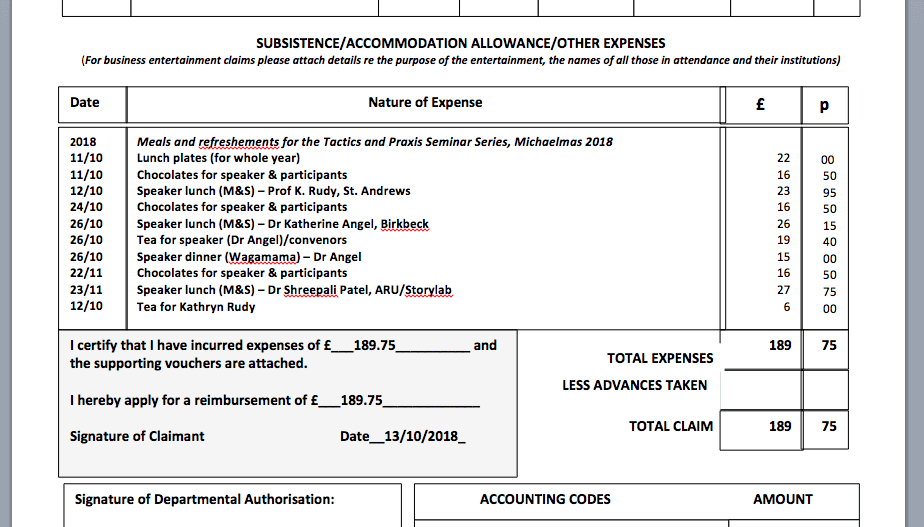

We encourage participants to bring their own lunch but also include a sharing of food and drink that is never excessive or ostentatious, but acts as a signal that sensory pleasure will be actively encouraged and valued in our gatherings. We supply vegan chocolates which allow for almost all dietary requirements; where possible, we continue conversations over tea or a further meal. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2 Expenses Claim for Tactics & Praxis Seminar

We also try to alter the atmosphere of the environment in which our interactions take place, by decorating the room with props, such as examples of creative work, books that inspire us, family heirlooms. A glass apple, a crochet mermaid tail, a grandmother’s tablecloth have been joined over the year by an array of other objects such as a giant letter ‘T’ (for Tactics) cushion, scented with home-grown lavender and made from a patchwork of upholstery samples which were received as a gift by one of the convenors. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3 Patchwork Tactics Cushion

We strive to create complicity and solidarity in our sessions, resisting atomisation and competition, rejecting hierarchy: our doors are open to everyone. We reject the patriarchal academic star system and performative celebrations of hierarchy that are so common in the presentation of colleagues at talks. We introduce our speakers with love and enthusiasm, rather than deference. In addition to their intellectual brilliance, we admire them for their other strengths and values: courage, creativity, activism, solidarity. We tell the true stories of how we came to connect with them and their work, rather than reproducing stock narratives rooted solely in matrices of professional renown and narrowly determined models of brilliance.

We work collaboratively as a group of women and all of our guests so far have identified as women. This is not a fixed rule that we have given ourselves. However, we have found a liberating and energising aspect of Tactics and Praxis has been found in the way group dynamics function differently when those who identify as women form a majority and set the tone for interactions. Our group is emphatically open to all genders and we have some keen male participants. Nevertheless, it is a ‘women’s space’ in the sense that all participants—ourselves included—feel able to contribute freely in a spirit of mutual nurturing, rather than one of competitive display. Writing in 1973-4, Rich noted the ‘familiar ring’ of discourse used to describe what happens in academic contexts: ‘defending, attacking, combat, status, banking, duelled, power, making it. They suggest connections— actual and metaphoric— between the style of the university and the style of a society invested in military and economic aggression’. (1999: 129) The prevalence of a masculine ideal of domination still permeates University life today, joined by the aforementioned emphasis on individual realisation and success. Through Tactics and Praxis we aim to contribute towards what Rich called a ‘female counter-force’. We join the many who have, over the years, responded to Rich’s still-relevant call to ‘choose what we will and won’t accept and what we will reject of institutions already structured and defined by patriarchal values’. (1999: 133)

To be clear, our understanding of women in a ‘female counter-force’ includes, as Sara Ahmed has put it, ‘all those who travel under the sign women’ (2018: 14), which is an infinitely diverse constellation with an array of different gaps and intersections. Whilst we believe it is vitally important to nurture shared pleasures and joy, we recognise that awkwardness, difficulty and anger can be necessary aspects of feminist work and pedagogy. Ahmed writes of women of colour creating tension in feminist groups: ‘you can be a killjoy at feminist tables because of who you are, what you say, what you do; because of a history you might bring up just by entering a room’. (2018: 176) At the University of Cambridge and elsewhere, students are often the ones leading the way in a feminist pedagogy that exposes the structural racism of our institutions. In her essay ‘Academia and Unbearable Whiteness’, Lola Olufemi asks that we ‘address the ideological reasons behind this institution’s insistence on relying on a singular form of knowledge production’ (2019: 57), an important reminder that structural racism and privilege are embedded in the institutional spaces we inhabit and lives we lead, as well as our curricula. Following Ahmed and bell hooks, we aspire to host gatherings where we contain and value difference and complexity, ‘where we can engage in open critical dialogue with one another, where we can debate and discuss without fear of emotional collapse’. (hooks 1994: 110) As three white, able-bodied, cis women, we have much work to do here; we do not intend to shirk from it.

Interlude: On Collapsing & Being Held

For me a really valuable aspect to being without fear of emotional collapse in Tactics and Praxis is that the group allows and sustains emotion and affect; in fact, you could collapse emotionally in joy, in grief, in anger, in excitement and it’d be fine; somehow. It’s possible to allow grief or anger or joy or excitement or incomprehension and to let it be known publicly without, yes, this is it, without fear of censure, comfortable in the fact the group will hold it without judgement. It’s been so powerful, for personal grief and depression but as part of the process of expressing anger at the inequities of this bloody patriarchal system and the everyday and/or institutional sexism we all encounter. (Seminar Participant)

Feeling Our Way

There was no doubt in our minds that something highly irregular was happening in institutional space as we carried Louise’s tall, wooden standard lamp across Trinity Hall Front Court to the room where the seminar would be held that lunchtime. We later brought down ornaments, books and props like those described above. When Kathryn Rudy, our speaker, arrived, the first thing she did was to ask us to close our eyes, and put into our hands something soft and dense. Our fingers felt long, large furry ridges on a woven background. ‘It’s cashmere corduroy’, she said and our eyes opened to bright pink-orange lines of cashmere along a backing of delicate, almond-green silk.

We had pre-circulated Cvetkovich’s chapter ‘The Utopia of Ordinary Habit: Crafting, Creativity and Spiritual Practice’ (2012). This encounter with texture resonated with Cvetkovich’s idea that craft could offer a ‘redefinition of what counts as politics to include sensory interactions with highly tactile spaces and with other people—or, in other words, feelings’. (2012: 177) Plunging our fingers, eyes closed, into a beautiful sensory object made with great skill, hard work and tenderness by a woman we had only just met felt like the professional and the personal colliding—it gave us hope and it felt joyful.

But Kathryn’s presentation was not only a sharing of the pleasures of her weaving practice: she spoke of her clinical depression and the profound loneliness of moving to Scotland, making friends with the coastline rather than other people. Her life became a pattern of walking on the beach, of weaving and of writing. She had difficulty making ends meet and was determined to get promoted so she could pay her bills. Caught in a productivity culture, she needed to write and publish. She did so, furiously. The walking and the weaving helped her write. The walking produced textures and colours that she wove with yarn into patterns on her loom. (Fig. 4) Her loom was an heirloom that helped her to resist the feelings of grey and nothingness she found in Scotland. She told us of the mountains and of walking high enough to burst through the clouds in the peaks to discover outrageously beautiful rainbows splashed across the sky. The cloud eats sound, disorienting one in space. The loom creates a huge sound, and is as physical and effortful as climbing mountains. Weaving, like archival work, is a heavy, physical labour.

Fig. 4 Kathryn Rudy, Don’t Let Go of My Waffle (photograph by Brendan Cavaunagh)

Thinking it through for our seminar, Kathryn observed that the walking, the feeling her way and the weaving were an intense training in noticing, which affected her academic work on medieval manuscripts. It became practice for an art historical method. Her noticing wove in and out of her work and time spent in nature. Touching the ‘clip’ of the sheep she made friends with, working unspun wool into her weavings, she thought about tactility in manuscripts. She noticed smeared images that told a story of a ritual of touching the book repeatedly in certain places. Sometimes those places were where textures met: smooth gold leaf and the rougher parchment.

In our collective discussion of these intersections between loneliness, depression, nature, weaving, and the multi-sensory qualities of manuscripts, we observed how the connections between intimate experience and professional life can be worth attending to and thinking about. In this session we did not only learn from Kathryn’s attention to these connections, but also began our own interweavings: paths towards a different way of understanding our individual and collective work.

Shreepali Patel’s session also made us think about the intersections between our personal experience and the political and social dimensions of our work. She situated her multi-screen and gallery work The Crossing, which we watched as an online short film for the seminar, in relation to her feelings of protectiveness towards her own daughter. The film grapples with how to transmit the disturbing testimony of a woman survivor of sex trafficking, seeking new ways of conveying an embodied experience of violent alienation. Among her powerfully innovative storytelling methods, Shreepali used drone filming to offer a non-human view of urban space, moving through the dimensions of the city in unfamiliar ways; this is interwoven with images and evocations of the vulnerability of the human body. (Fig. 5) The film makes palpable the co-existence of London as a buzzing centre of commerce with a hidden economy of brutal sexual exploitation.

Fig. 5 Shreepali Patel, The Crossing

Our commitment to ‘feeling our way’ arises in the tradition of feminist pedagogy, as summarized by Megan Boler:

[F]eminist pedagogies emphasize how processes of learning, social change and education are intimately bound up with feeling. Integrating theory and praxis, education practices enabled students to understand emotions as a legitimate source of knowledge’. (2015: 1491)

Importantly, thinking about The Crossing, which manages to tread a careful line between proximity and distance, such legitimisation of emotions and embodied experience remains alert to what Boler has theorised as ‘the risks of empathy’, too often sold as ‘a teachable prescription to remedy ills ranging from injustice to inefficient workplaces’. (2015: 1492) Rather, Boler calls for a ‘pedagogy of discomfort’, which may disrupt our assumptions and sense of self as we re-evaluate ‘cherished beliefs and assumptions inherited from the dominant culture’. (2015: 1492) As Fisher simply proposes, ‘feeling helps us define what the world is like and how we want to change it’. (1981: 21)

Making & Finding

To make is to feel; to make is to find. Our speakers have all shared different ways in which, feeling their way, they have made things and found new understanding.

Jane Partner’s seminar, ‘The Muses’ Anvil: Metalwork, Academia and Creative Inspiration’, offered a richly textured exploration of the encounter between practical making and intellectual labour. Jane gave us a fascinating account of her own jewellery-making practice in relation to her research in the art and literature of the Renaissance. Images of her workshop alongside those of her historical forebears drew us into the kinetic, muscular and fiery business of shaping metal, a sense which flowed into both new and historical perspectives on writing as practical, creative graft and the role of tools and spaces in such making. Looking at her exquisite jewellery, we considered again the politicised distinctions drawn between art and craft. (Fig. 6)

We talked about the intimacy of jewellery, its specificity to the wearer and her visual language, and about the body as a place of vulnerability and self-expression. Jane’s title also moved us to question the distinction between the muse, so often framed as the passive object of masculine inspiration, and the beloved friend for whom we create a gift.

Fig. 6 Jane Partner’s Sculptural Metalwork Jewellery

Jane’s session took the group into a discussion about the fragility and hostility of many understandings of academic work, and what it is supposed to mean to have an academic ‘career’. Why is the parallel pursuit of creative practice so often deemed to be somehow inimical to our research? What kind of perspective is being valued, if our interlocutors think that doing other things diminishes our understanding? What kind of gatekeeping is being perpetuated by the ‘all or nothing’ vision of academic research, which recoils even at part-time posts, never mind at recognising the status of every researcher as an embodied individual with a life which might, indeed must, radiate in multiple directions?

Fig.7 Isabelle & Louise (Photograph by Georgina Evans)

When Emma Cayley, arrived in the seminar room, the first thing she did—after introducing us to her latest Bratz made-under doll—was array her reclaimed dolls, cleansed of makeup (with spookily bare eye sockets) and stripped of their pop-star costumes, in a crescent moon around the tables we set up for her workshop. Holding the dolls, dressing them, and giving them new faces was both pleasurable and discomforting. There was a feeling of joy and care in bringing the dolls back to life, creating a new image, and reclaiming their style from the extreme sexual objectification implied in the Bratz features and clothing. (Fig. 7) At the same time, the naked, faceless dolls felt vulnerable, even to our own internalised and conflicted feelings about female beauty and appearance, drawing our attention to ‘the enmeshing of sex industry practices throughout culture’ (Reist 2009: 13), including in children’s culture.

Interlude: Katherine Angel’s Unmastered

1. I grew up acutely, unhappily, aware of the pull of sex, of what young female bodies could elicit.

I remember standing on a bus, around the age of thirteen, feeling the heavy stare of a sagging, tired man, around the age of my father. It was threaded with hostility; hostility and desire. It wanted me, but it hated me for making that want arise. …

I remember a pushy older boy at school lifting my skirt up as I passed by with friends. I had a glass of coke in my hand; I poured it neatly, decisively, over his gelled head. …

3. I was always aware, I think, of my hunger for men: the sharp arrow of excitement when they walked into a room. Of wanting their hard, uncompromising bodies. Their tough surfaces. Their urgent, wilful desire.

4. I wanted to plunge into my senses. To bring my body to life! (Angel 2014: 182‑83).

Seeing so many of those dolls in one space created a striking visual image of the pervasive commodification of the female body. There were so many different shades of doll but only one anatomically impossible hour-glass figure and face shape. Here too was an image of the many ways in which both our bodies themselves and our feelings about them do not belong to us. In our hands, the dolls became children again, freed from the burden of sexual exploitation. Yet often they mirrored us in terms of colouring or style: Louise and her made-under doll (both in Fig. 7 above) were not atypical in this ‘mini-me’ aspect. But they still tended to conform to certain ideals of prettiness and femininity, such as large eyes or lack of skin blemishes. Our choices were not, could not be neutral. There was a pedagogy of discomfort at work in the seminar, alongside the utopian atmosphere and shared delight in diversionary tactics at work.

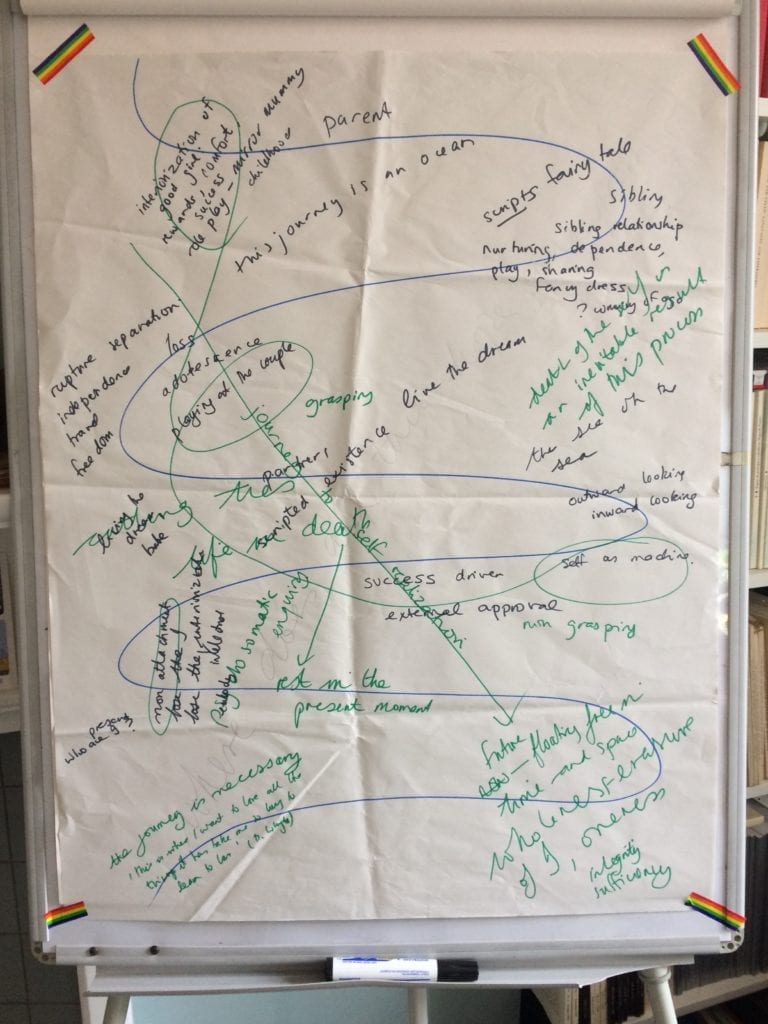

Our next session, a workshop led by Afrodita Nikolova, brought further contemplation of the intertwining of creating with research, with a focus on Susan Finley and Gary Knowles’ collaborative essay ‘Research as Artist/Artist as Researcher’ (1995). Before coming to her session, we watched Afrodita’s powerful TEDx University of Cambridge talk (2018) on poetry as a research tool and, in the session itself, were lead on a reflexive journey of self-enquiry through a variety of techniques that she has developed or brought into dialogue with one another. Part of the session involved using a river journey mapping tool and Dixit cards to enquire into our own experience and motivations to increase our self-knowledge. (Fig. 8) There was much pleasure and laughter in this session but there were also uncomfortable, sometimes disturbing, moments of self-recognition, silences and even gasps, which Afrodita held compassionately, ethically and with integrity. Many of us achieved deep insights which are permitting us to approach our identities and praxis in more informed ways; insights into the ways in which we split our identities between personal and professional space or how past pleasures have given way to present pressures.

Fig. 8 An Example from One of the Participants Inspired by Dixit Cards (with permission, Photograph by Louise Haywood)

Our seminars have offered insight into the diversity of ways in which creative practice can interact with academic work. Following from Finley and Knowles’s exploration of how ‘artistic and aesthetic experiences and events have shaped our thinking about research’ (1995: 110), we find that it might not be a question of treating praxis as a traditional research method with a predetermined goal. Finding through making often seems to come through a contemplation of the gaps between an academic project and something apparently ‘outside’ and disconnected from it. What if this were another form of Milner’s idea of ‘framing the gap’?

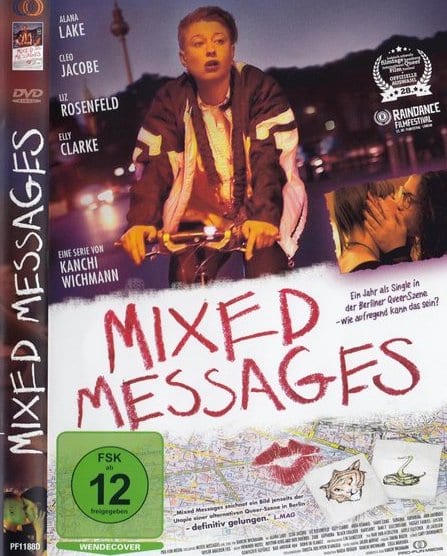

Leila Mukhida spoke about these gaps in her session, reflecting on her work in filmmaking and her work as a scholar. Her hands-on creative work—making a film about queer Muslims in Berlin and producing a humorous web series about the Berlin lesbian scene—seemed to belong to a different sphere from her research. (Fig. 9) She had seen her films as focused on storytelling and the representation of individuals, in opposition to her usual interest in the subversive power of experimental aesthetic forms. Yet Leila’s attention to what film can do, as well as what it can show, revealed resonance between her filmmaking and a research project on an unmade film script, conceived by exiled members of the Frankfurt School in 1945-46. In her films, she was presenting people who tended not to fit recognisable, familiar images: showing Mixed Messages (2017) in a ‘straight’ Festival, the audience were baffled by the opening scene depicting an awkward breakup between a queer, polyamorous couple. The screenplay for Below the Surface, on the other hand, collectively composed by Siegfried Kracauer and others, including an MGM scriptwriter, exaggerated identifiable stereotypes (signalled through accents and markers of ethnicity, religion and class) with the aim of testing audience prejudices. Thinking about these very different works alongside one another raised important questions about the relationship between subject and audience in film—about orthodoxies of spectatorship and how to break or expand them, and the role that pleasure (aesthetic, comedic) might play in that. Leila’s experience in the making of films confronted her with living experience—for example working, in The Greatest Gift (2011) alongside co-director Subir Che Selia, with people whose identity as queer and Muslim needed to be protected for their safety—that can often be kept at a distance in academic writing about film.

Fig. 9 DVD Cover for Mixed Messages (courtesy of Leila Mukhida).

Threshold

This seminar series, along with its myriad offshoots in terms of coalitions formed, informal discussions both on and off-line, creative stimulation and future planning, has given us hope because it illuminates a shared appetite for change and for collaborative experimentation. We are heartened that we have been given the resources we need to continue running the seminar for a second year, with the chance to host another wonderful set of guest speakers, each of whom will bring a new perspective to the ongoing conversation. The momentum built up collectively over this year has also helped us secure funding and practical support to hold a Tactics and Praxis conference in July 2020, and, with that, the chance to think about how the academic conference model can be remade in a better, more collaborative form. The same energy is flowing into proposals for other ventures, which we hope will help us share what we have gained (in every sense), more widely across our community, especially with those who have not thus far been present at the seminars. One of the most exciting, and pressing, of our next challenges is to extend what we have learned in the relatively protected space of the seminar into established and dominant pedagogical structures which have, like so much in academic institutions, for too long gone unquestioned. We are confident that we are not alone in wanting to do things differently.

Notes

[1] In a post script, we wanted to add how different the experience of being reviewed for a feminist publication was from other review experiences we have had: both the reviewers broadly agreed (when did that ever happen?), we were not instructed to cite anyone, and the advice was phrased positively and constructively so that we were able to act on it without angst. This piece is the result of wide collaboration (not just the three of us but also the seminar participants) and the reviewers have been part of that process too.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our seminar speakers, listed below, and participants for many of the items cited. Although written by the three of us, this is the work of many more, including:

Katherine Angel, writer, history of sexuality specialist (Birkbeck, London)

Emma Cayley, gender activist, workshop leader, medieval French specialist (Exeter)

Catherine Grant, videoessayist, film studies specialist (Birkbeck, London)

Leila Mukhida, film-maker, German and Austrian film studies specialist (Trinity Hall, Cambridge)

Afrodita Nikolova, poet, workshop leader, arts-practice in prison and education specialist (Wolfson, Cambridge)

Jane Partner, artist, silversmith, Early Modern English specialist (Trinity Hall, Cambridge)

Shreepali Patel, film-maker, Director of the Storylab Institute (https://aru.ac.uk/storylab), multiplatform and cross-disciplinary practices specialist (Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge)

Kathryn Rudy, weaver, medieval art historian (St Andrews)

Our full programme is available on the non-institutional site: https://www.tacticsandpraxis.org/.

Readings and visual materials are hosted on Moodle at the University of Cambridge: please contact us for access.

Our Twitter feed is actively curated @TacticsPraxis.

We welcome collaborations.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2018), Living a Feminist Life, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Angel, Katherine (2014 [2012]), Unmastered: A Book on Desire, Most Difficult to Tell, London: Penguin.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah (2018), Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Berg, Maggie & Barbara K. Seeber (2016), The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy, Toronto, Buffalo & London: University of Toronto Press.

Boler, Megan, (2015), ‘Feminist Politics of Emotions and Critical Digital Pedagogies: A Call to Action’, PMLA, Special Topic: Emotions, Vol. 130, No. 5, pp. 1489-1496.

Boulous-Walker, Michelle (2011), ‘Becoming Slow: Philosophy, Reading and the Essay’, in Graham Oppy & N. N. Trakakis (eds), The Antipodean Philosopher: Public Lectures on Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand, Volume 1, Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto & Plymouth UK: Lexington Books, pp. 265-280.

Cvetkovich, Ann (2012), Depression: A Public Feeling, Durham & London: Duke University Press.

De Certeau, Michel (1984), The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Finley, Susan & Gary Knowles (1995), ‘Researcher as Artist/Artist as Researcher’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 110-142.

Fisher, Bernice (1981), ‘What Is Feminist Pedagogy?’, The Radical Teacher, No. 18, pp. 20-24.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen (2009), Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology and the Future of the Academy, New York: New York University Press.

Gill, Rosalind (2010), ‘Breaking the Silence: The Hidden Injuries of the Neoliberal University’, in Rósín Ryan-Flood and Rosalind Gill (eds) Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections, Abington and New York: Routledge.

Grant, Catherine (2019), The Haunting of the Headless Woman, https://vimeo.com/301095918 (last accessed 28 August 2019).

Han, Byung-Chul (2015), The Burnout Society, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Harrison, Rebecca (2018a), ‘On Brilliance: Making Light of Women’s Creative Labour’, MAI: Feminism and Visual Culture, No. 1, http://maifeminism.com/on-brilliance-making-light-of-womens-creative-labour/ (last accessed 6th September 2019).

Harrison, Rebecca (2018b), ‘Athena SWAN is an Ugly Duckling’, Times Higher Eductation, 3 May 2018, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/athena-swan-ugly-duckling#node-comments (last accessed 27 August 2019).

hooks bell (1994), Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, Oxford: Routledge.

Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve (1999), A Dialogue on Love, Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Milner, Marion (2010 [1950]), On Not Being Able to Paint, New Introduction by Janet Sayers, London & New York: Routledge.

Mirowski, Philip (2014), Never Let a Serious Crisis Go To Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown, London & New York: Verso.

Nikolova, Afrodita (2018), ‘Why Spoken Word Poetry is an Essential Research Method’, TEDx University of Cambridge, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xO-qPnuy8M (last accessed 17 October 2019).

Olufemi, Lola (2019), ‘Academia and Unbearable Whiteness’, in A Fly Girl’s Guide to University: Being a Woman of Colour at Cambridge and Other Institution of Power and Elitism, Birmingham: Verve Poetry Press, pp. 56-68.

Pajaczkowska, Claire (2007), ‘On Humming: Reflections on Marion Milner’s Contribution to Psychoanalysis’, in Lesley Caldwell (ed.) Winnicott and the Psychoanalytic Tradition: Interpretation and Other Psychoanalytic Issues, London: Karnac Books, pp. 33-48.

Rich, Adrienne (1979), ‘Toward a Woman-Centered University’, in On Lies, Secrets and Silence: Selected Prose 1966-1978. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 125-155.

Stewart, Kathleen (2018), ‘Writing, Life’, PMLA, Vol. 133, No. 1, pp.186-189.

Tankard Reist, Melinda (2009), ‘The Pornification of Girlhood: We Haven’t Come a Long Way, Baby’, in Melinda Tankard Reist (ed.) Getting Real: Challenging the Sexualisation of Girls, Melbourne: Spinifex, pp. 5-39.

Films & TV Series

The Headless Woman/La mujer sin cabeza (2008) dir. Lucrecia Martel.

The Greatest Gift/Das Schönste Geschenk (2011) dir. Subir Che Selia and Leila Mukhida.

Mixed Messages (2017), Web Series, dir. Kanchi Wichmann.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey