Survival of the Knittest: Craft and Queer-Feminist Worldmaking

by: Daniel Fountain , December 13, 2021

by: Daniel Fountain , December 13, 2021

In A Theory of Craft (2007: 55), Howard Risatti suggests that ‘in one important way or another, by containing, covering, and supporting, craft objects help in our struggle for survival in an otherwise indifferent, if not hostile, world.’ Risatti goes further to explain that craft is a physiological necessity, but he does not give an indication as to who ‘our struggle’ might encompass, and neither does he acknowledge that this assertion may be more pertinent to some social groups over others. In this article I therefore argue that for queer individuals this notion of craft as a survival strategy has perhaps never rung truer. The title of this article, Survival of the Knittest, is a crafty pun on the phrase ‘survival of the fittest,’ which we associate with a process of adjusting to hostile environments to ensure survival. After all, craft, or more broadly the practice of crafting, is an essential part of queer-feminist survival. This article therefore defines craft as a process, as ‘a way of doing things’ and a ‘way of being in the world,’ rather than necessarily just a fixed set of physical objects or skilled practices. (Adamson 2007: 3-4; Cvetkovich 2012: 168) Both queer lives and sexual practices often rely on processes of crafting—of crafting of community and crafting of the self: ‘there is no guidebook or inherited cultural roadmap … [t]hese are the things we have to create ourselves’. (Harrod 2017: 33)

In order to establish a critical frame of reference from which to build upon, I begin the article with some key context around the feminist legacies of craft, before moving on to talk about notions of queer craft(ing), drawing on examples such as the exhibition Queer Threads and the Museum of Transology collection. The article then focuses on the work of two queer artists, LJ Roberts (b.1980) and Jesse Harrod (b.1979), as a site for analysis to explore these connections between craft, survival, and queer-feminist worldmaking. Both of these artists engage with textile techniques and processes such as knitting and macramé, which not only ruminate on the legacy of 1970s feminism and fiber art, but also offer new and more inclusive perspectives on worldmaking drawn from their own identities, subjectivities and experiences from the present.

Feminist Legacies of Craft

Several scholars have persuasively argued that the development of a hierarchy of the arts coincided historically with a similar one between the categories of male and female. For instance, in Rozsika Parker’s influential text The Subversive Stitch (1984: 5), she argues that ‘the development of an ideology of femininity coincided historically with the emergence of a clearly defined separation of art and craft.’ Deemed ‘outside’ the modes of masculine, capitalist production, these fiber and textile craft practices were historically considered unproductive activities and hobbies, particularly due to their ability to be conducted in a home environment. She also observes that this gendering of craft continued well into the eighteenth century, where tasks were ‘consigned to the “appropriate” gender’ within the academy. (Parker 1984: 5; Tucker 1996: 52) In turn, this lasted at least into the 1980s, particularly in Britain, where ‘boys’ would study carpentry and ‘girls’ would study embroidery. (Katz-Freiman 2008: 180)

Many artists who formed part of the second-wave feminist movement sought to deliberately exploit this relationship between craft and gender, using craft as a ‘weapon of resistance’ to unpick and unravel the very binaries between high/low, art/craft, male/female. (Parker 1984: xix) This was marked by the revolution of what became known in the American tradition as ‘fiber art,’ which by the late 1970s had come to signal any work that utilised techniques such as stitching, quilting, knotting, knotting, braiding, beading, and so on. (Auther 2010: 7) Fiber artists recognised the potential of categories such as ‘soft art’ or ‘soft sculpture’ to traverse the divide separating art from craft. (Auther 2008: 29) In particular, feminist artists during this period saw fiber art as ‘a highly productive force in the art world by virtue of its perceived inferiority,’ and used these very techniques to push back against stereotyping of fiber-crafts as domestic, passive and inherently feminine. (Auther 2010: p.xxx) As Elissa Auther (2008: 31) astutely summaries, this ‘shared marginality between the female traditional artist and the contemporary feminist artist helped the latter negotiate the paradoxical goal of seeking recognition in the mainstream art world, while at the same time attempting to critique it.’

In the 1970s, art projects such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Womanhouse certainly paved the way for much of the feminist art we see today. This was an exhibition initiated as part of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Programme, which encouraged their students to organise and generate content for the exhibition. It took place at an abandoned mansion in Hollywood, running from 30th January to 28th February 1972. Artworks on display included the likes of Faith Wilding’s Crocheted Environment (1972)—more commonly known as ‘Womb Room,’—which was an immersive installation of a web-like crocheted structure that formed a cosy environment in the small, dark room in which it was exhibited. However, while such projects have been well-documented, academics still often approach craft purely through the lens of gender rather than sexual identity, despite there having been landmark exhibitions uniting both. One of these key exhibitions was the 1980 Great American Lesbian Art Show which took place at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, California, from 3rd to 31st May. The project aimed to celebrate the work of queer-feminists who were engaging with craft-based processes to explore their identities as both female and lesbian [1]. It marked a key intersection between the gay and women’s liberation movements, introducing at-the-time newly coined terms, such as ‘lesbian feminist’. (Hammond 2000a: 63) Its goals included: ‘to celebrate lesbian art by making it public, visible, and accessible; to build a national network of lesbian artists and a permanent slide collection of lesbian art; and to increase awareness of the power of lesbian vision and sensibility’. (GALAS Inform-Hers Packet, in Thompson 2010: 263) For the artist Harmony Hammond (b.1944), ‘lesbian art’ represented what she called a ‘braid with three strands … gender, sexuality, and art’. (Hammond 2000b: 10) She adds, ‘[e]ach strand touches the others as it weaves back and forth across the center line, giving it dimension, fullness, and presence, a flexible rope of incredible strength and beauty’. (Hammond 2000b: 10) Hammond exhibited two sculptures at this exhibition, Adelphi and Durango (both 1979), which did not overtly represent lesbian bodies, but rather evoked what she called ‘sensuous times and spaces between women’. (Thompson 2010: 266) In common with many of Hammond’s sculptures created between the late 1970s and mid 1980s, they were made of wrapped fabric strips which she saw as a ‘creating out of self’. (Thompson 2010: 266) Skin-like, tactile, sensuous, and a record of hand and holding, the corporeal process of making represented a deepening awareness of her own desires; desires which included same-sex attractions. (Thompson 2010: 266; Bryan-Wilson 2017: 84) She therefore sought to ‘give form’ to both herself and her sexual feelings through the very materials associated with women’s work; resulting in works with ‘soft’ looking exteriors, but with incredibly ‘strong cores’. (Reed 2011: 192)

Queer Craft(ing)

In her book Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017), Julia Bryan-Wilson begins to open up an important avenue for this queer interpretation of craft—what she terms a form of ‘queer handmaking’. (Bryan-Wilson 2017: 40) She illustrates this through an analysis of various works that include the trash(y) homemade costumes of drag troupe The Cockettes, panels from The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, and also Hammond’s own Floorpieces (1973) which were created the year that the artist publicly came out as a lesbian. Particularly in relation to Hammond’s floor works, Bryan-Wilson (2017: 89) discusses these as euphemistic for ‘going down’—a term used to describe oral sex between women—thus resonating as a kind of lesbian visual politics. She also suggests that Hammond’s handiwork especially ‘explodes one persistent assumption about craft as rooted in the domestic, primarily straight, domestic sphere’. (2017: 88) Bryan-Wilson (2017: 84) further explains: ‘[t]he three strands of the braid invoke what I want to argue is for her [Hammond] a radical queer “third space” that represents an orientation beyond the heteronormative binary.’ This ‘third space’ not only represents a move beyond the heteronormative binary in Hammonds’ own work, but it is also reflective of Bryan-Wilson’s own approach to writing about craft, which seeks to move beyond heteronormative concepts of the ‘home,’ the ‘domestic’ and the ‘feminine.’ Such a perspective encourages readers to consider the particular relationship between gender, craft and sexuality—which this article also advocates.

More recently, the exhibition Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community sought to explore the associations between fiber art and queer identity, showcasing a far more diverse array of artists identifying as LGBTQ+. It was curated by John Chaich, and was first shown at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York from 17th January to 16th March 2014. It has since toured around the United States in various different iterations, and with some new artists being chosen to exhibit each time. Aside from including work by both Roberts and Harrod, the initial exhibition included many other influential queer-feminist artists who work in fiber, such as Shelia Pepe and Allyson Mitchell, whose work Ann Cvetkovich discusses in her book Depression: A Public Feeling. (2012: 154-202) In the Queer Threads exhibition pamphlet Hunter O’Hanian, the Leslie-Lohman’s Director at the time, stated that it ‘is only natural that artists seeking to explore a queer sensibility would look to something so ubiquitous to explore a perspective that may seem so foreign’. (O’Hanian 2014: 2) Despite these landmark shows of queer-feminist art, and such assertions that queer artists would naturally look to craft as an appropriate medium, the interest of queer-feminist artists engaging with craft has continued to stand outside of academic interrogation until recent years. This article therefore suggests that attention needs to be given to the ways in which craft’s own historic position as ‘other’ to fine art might intersect with non-normative gender identities and sexualities.

Although this article has so far also approached craft in terms of a set of materials and practices—that is, fiber art—it hopes to advocate that craft might more usefully be viewed as a process, as in crafting an identity, or crafting a community. Although not necessarily concerned with the intersections between craft, gender, and sexuality, Glenn Adamson (2007: 3-4) is a leading critic in the field of craft studies who has suggested that craft ‘only exists in motion. It is a way of doing things, not [just] a classification of objects, institutions, or people.’ Such conceptualisations of craft allow for it to be theorised as a wider field of cultural production which allows makers to move ‘nimbly between and beyond high and low’ and between any materials they see fit. As Adamson acknowledges, ‘craft’s inferiority might be the most productive thing about it.’ Furthermore, with their nomadic potential and status as a ‘low’ or ‘marginalised’ form of making, fiber art is particularly ripe for queer work.

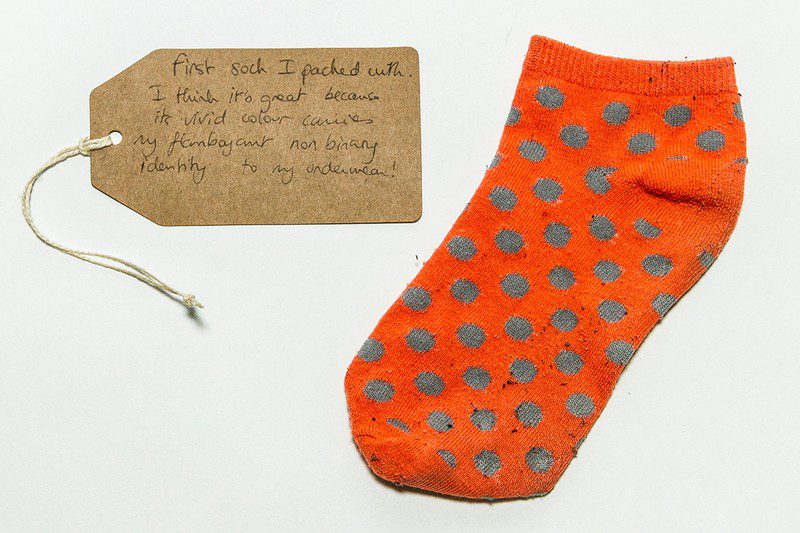

Bryan-Wilson also reminds us that these materials are literally woven into the fabric of everyday life, particularly for queer people. As she observes: ‘non-gender-conforming folks like drag queens, drag kings, butch lesbians, and femmy fags (as well as transgendered folks who aim to pass “seamlessly,” to invoke a sewing metaphor) have had to make their own clothes, significantly tailor garments, and invent body-altering modifications’. (2017: 60) There is no denying that craft scholarship remains heavily rooted in both heteronormative and cisnormative binaries. However, Bryan-Wilson’s long list of queer individuals who enact processes of crafting on a daily basis reminds readers that we need to acknowledge the complex role that craft(ing) has for those who identify as gender non-conforming, non-binary, and transgender, to name but three examples. The ongoing collection project called the Museum of Transology, curated by E-J Scott, offers another prime example of this. When E-J undertook ‘top surgery’ (a mastectomy), they kept everything from their room: the hospital gown from one of their procedures, the needle used for their morphine prescription and the pillowcase from their bed. (Tsjeng 2017) Scott’s own personal collection eventually grew into the museum as it is known today, encompassing hundreds of deeply personal and everyday items from trans people from across the United Kingdom. Donors are also asked to fill out a travel tag in their own handwriting, explaining the significance of the artefact to their own gender journey. (Gander 2017) The amount of textile objects in the collection is vast; signalling that they do indeed play an important role in the fashioning of the self. Aside from items like dresses and trousers, there are other items of clothing or textiles which have been used craftily, inventively, and queerly. For example, there is an orange spotty sock with a label that reads: ‘first sock I packed with. I think it’s great because its vivid colour carries my flamboyant non-binary identity to my underwear!’ (Fig.1) Packing is the act of wearing padding or a phallic object in the front of underwear in order to provide a bulge, thus giving the appearance of having a penis. Silicone packers are available, but individuals who want to pack often begin to experiment with using items that are more readily available and less costly, like a ball of socks, in the first instance. Another object in the collection is a breast binder, which is used to give the appearance of a flatter chest. The label reads ‘this was my first binder, I quickly grew out of it and bought more, but when I grew out of those, I couldn’t afford a new one so used parts of this one to make them bigger’. (Fig.2) Through its collection of objects, the Museum of Transology challenges the idea that gender is fixed, binary and biologically determined. (Brighton Museum n.d.) In this case, it also supports in demonstrating how hand-crafted objects (particularly textiles) can support queer subjects in crafting their own identities.

Having established an important critical context relating to the legacies of feminist craft, as well as the role of craft for many members of the queer community today, this article now moves towards a discussion of artworks by LJ Roberts and Jesse Harrod. Much like Hammond, their respective bodies of work seem to unite these strands of gender, sexuality, and art, demonstrating a queer-feminist approach to materials and practices.

LJ Roberts

LJ Roberts finds that the issues of marginality they encounter as a queer, gender non-conforming and non-binary person mirror the positions of textiles and craft within visual culture. (Fountain & Roberts 2020) Reflected at both a material and conceptual level of their practice, the artist therefore explores ideas of marginality through processes of handicraft which have also been marginalised and relegated to the status of ‘other’ throughout history. This is perhaps best exemplified in their knitted work The Queer Houses of Brooklyn in the Three Towns of Breukelen, Boswyck, and Midwout during the 41st Year of the Stonewall Era (2011).

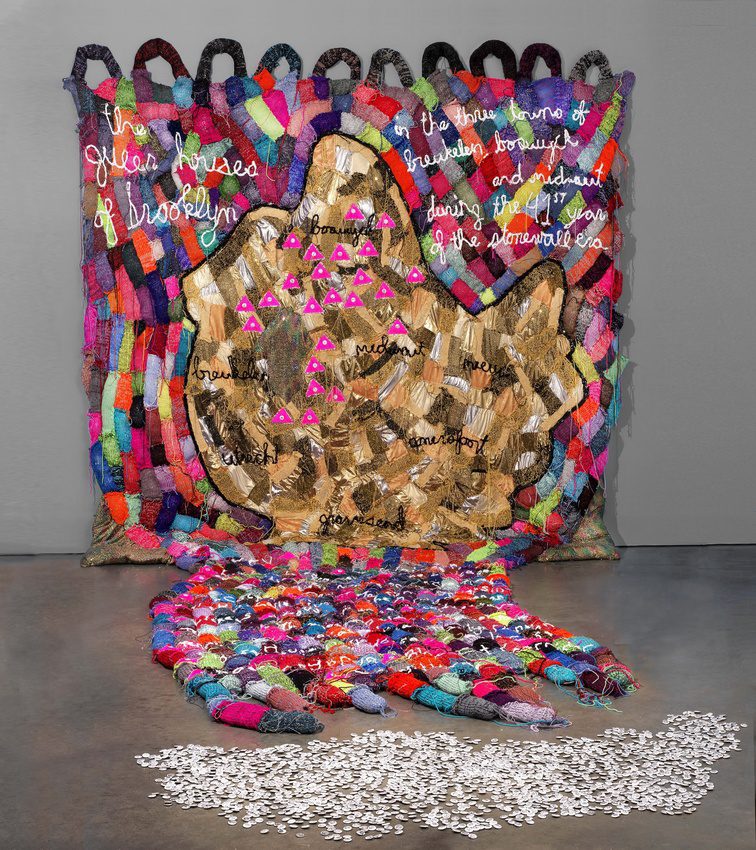

The artwork celebrates the crafting of alternative kinship structures. It takes the form of an abstract knitted map of Brooklyn, and the locations of twenty-four queer collective houses are marked by pink triangles, each adorned with a badge to represent its respective house name. (Fig.3) The pink triangle is an important symbol in queer culture, having been inverted and reclaimed as a source of strength from its darker origins as a Nazi concentration camp badge during World War Two, where it was primarily used to identify homosexual men [2]. The map is based on an original drawing by Daniel Rosza Lang/Levitsky which plots the locations of queer collective houses across Brooklyn between 2010 and 2011. The artist designed the map for a community building event called Queer House Field Day—an event organised by QUORUM (Queers Organizing or Radical Unity and Mobilization)—to make visible the geography of these houses and to connect them to the underlying colonial history and gentrification of Brooklyn; hence the Dutch names present within the work’s title. (Smithsonian American Art Museum 2012)

The large, knitted version created by Roberts cascades from the wall to the floor, and at the end of the fringes there is a sea of scattered badges designed by another collaborator, Buzz Slutzky, which viewers can ‘go down’ or ‘bend over’ to pick up and take home. The take-away element provides a subtle nod toward the work of Félix González-Torres (1957-1996) who is well-known for his use of multiples through works such as Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), and whose work remains an important point of identification for Roberts. Each of the twenty-four different badge designs correspond to a house on the map, and features their own characteristic name and symbol which subvert traditional iconography associated with coats-of-arms and archaic heraldic devices. Rather than lions, crowns and shields, there are vulvas, leather daddy devils and pansies to illustrate their respective house names: Le Pouse Palais, Den of Sin, and Pansy Commons, for instance. (Fig.4)

Given that the work celebrates the existence of alternative kinship structures, it can be said to exemplify the concept of ‘queer worldmaking’ which has been widely credited to Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner’s essay Sex in Public (1998). The aim of their text, Berlant and Warner (1998: 548) argue, is to describe ‘the radical aspirations of queer culture building: not just a safe zone for queer sex but the changed possibilities of identity, intelligibility, publics, culture, and sex that appear when the heterosexual couple is no longer the referent or the privileged example of sexual culture.’ Writing from the position as a ‘queer femme, a housing organiser in New York City, and a founder of a queer home in Brooklyn,’ Katie Goldstein (2018: 269) rightly notes that ‘home can be a fraught place for many queers.’ They add: ‘[t]he act of creating queer homes redefines what home is and can be, and it challenges the invisibilisation and marginalisation of queer community’. (Goldstein 2018: 269) In Goldstein’s view, ‘[c]reating queer homes puts a queer mark on a non-queer landscape and, through that act, demands that queerness be recognised as an identity that must be seen’. (2018: 269) Roberts’ work therefore quite literally enacts this process of making queer homes visible, using the iconic symbol of the pink triangle to put a queer mark on a non-queer landscape.

To construct the work, Roberts utilised a wide range of methods and techniques such as a toy Barbie knitting machine, single-strand hand embroidery, a small sock-making machine, quilting, and appliqué. Roberts notes that as a queer person who struggled with being raised in a conservative suburb just outside of Detroit, textiles have been a pertinent material through which to work through such ideas. Aside from being ‘crafty,’ most of these methods are portable, accessible, and can adapt to a variety of circumstances, which Roberts confesses ‘is also how I aim to move through life’.(Fountain & Roberts 2020) Other works such as Portraits (2011-)—a series of small 4’’ x 6’’ embroideries depicting Roberts’ kin—are often stitched by the artist on the subway and then stashed away in their backpack. As a homespun textile piece, The Queer Houses of Brooklyn is, therefore, particularly fitting for such a commentary, serving as a metaphor to express how queer people often craft the houses they are ‘born’ into. The piece is also assembled, patched, and unites a variety of individual knitted pieces which can be seen as a poetic metaphor on the politics of queer community building. (Fig.5)

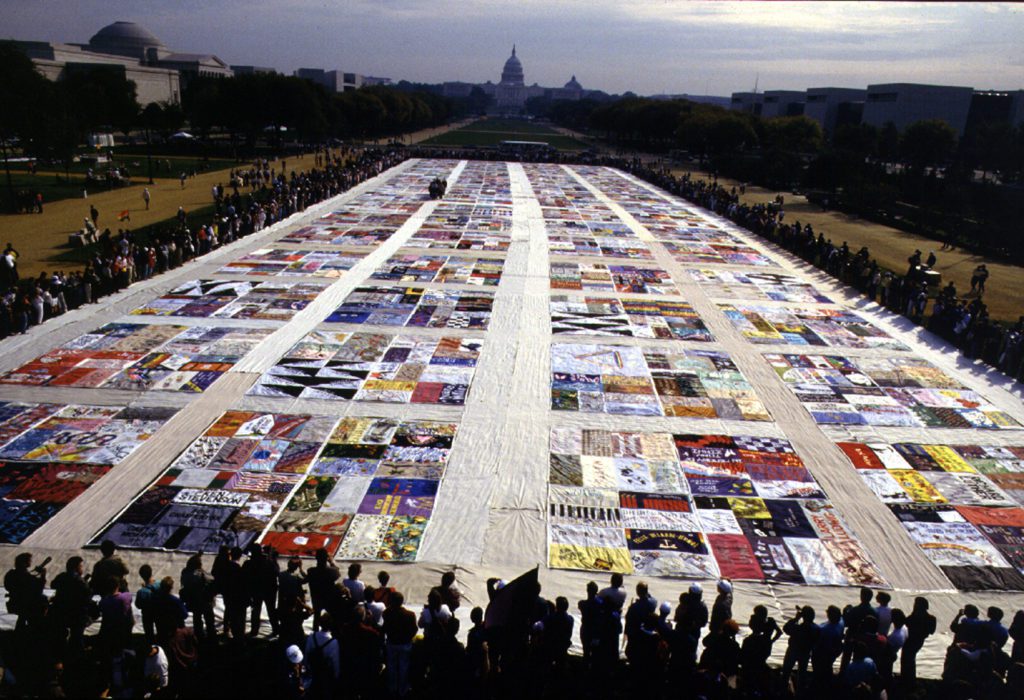

Its large scale and patched nature directly references community stitching projects such as The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt which greatly inspired Roberts when they were coming to terms with their identity. (Fig.6) At the age of 15 they were enrolled at an all-girls boarding school in Maryland, and were the only student who opted to go and see the Quilt displayed in its entirety on the Washington Mall when it was offered as a field trip. ‘It was the first time I had seen a queer collection of symbols … seeing rainbow flags and pink triangles and a lot of love expressed was a really profound thing,’ they recall .(Bowdoin College 2016) The AIDS Quilt, as it is more commonly known, was initiated on the 27th November 1985 by the activist Cleve Jones, at a candlelight vigil in the Castro District of San Francisco to mourn the murder of Harvey Milk. Given the increasing numbers of people dying in the District, Jones and a friend named Joseph Durant handed out blank placards and marker pens so that attendees could inscribe these with the names of their kin who had died from AIDS-related illnesses. (Jones 2000: 105) Rather than discarding the placards after the vigil had ended, demonstrators placed their boards on the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building as a symbol of resistance against President Reagan’s administration. (Jones 2000: 106) Jones (2000: 107) recalls an epiphany in front of the growing patchwork of names: ‘[s]tanding in the drizzle, watching as the posters absorbed the rain and fluttered down to the pavement, I said to myself, It looks like a quilt. As I said the word quilt, I was flooded with memories of home and family and the warmth of a quilt.’ The project is dedicated to a wide range of individuals who have died of AIDS-related causes, and is ongoing—it is currently the largest community art project in the world, consisting of around 48,000 individual memorial panels at the time of writing. (AIDS Quilt n.d) Each panel measures three feet by six, the average size of a human grave. (Hawkins 1993: 97) Eight of these panels are then sewn together by the Foundation to create a 12ft x 12ft ‘block.’ Although the blocks could be shown independently, each individual panel would therefore never be shown alone; the intention is ‘to see each name—each life—not as isolated, but as ensconced in a ‘visual dialogue’ with one another. (Bryan-Wilson 2017: 190) The interdependency of the blocks is therefore vital to the way the AIDS Quilt operates on a formal level. This sense of community is echoed in patchworked nature of The Queer Houses of Brooklyn in which many disparate sections are united together through the reparative stitch. Here, the use of thread parallels the potential for connectivity: ‘as individuals we are strands; as communities we are interwoven’. (Chaich 2014: 3)

Although The Queer Houses of Brooklyn is now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the work continues to live on outside of the institution through the endless supply of badges designed by Slutzky. That said, the notion of the queer world as ever-changing must not go unacknowledged, particularly given that many of the collective houses the work illustrates have since disbanded or have had to relocate to new apartments as a result of rising rents and the gentrification of queer spaces. The work, completed in 2011, therefore marks a specific snapshot in time when queer individuals could afford to live in closer proximity to one another. Looking at the work retrospectively, the loose threads that dangle down from each of the knitted sections seem to foretell the fate of many of these communities that have since come undone and no longer exist. A staunch traditionalist would argue that craft requires great skill, but many queer artists working in fiber deliberately work with more ‘sloppy’ aesthetics in order to deliberately subvert, or queer, dominant hierarchies of value and taste [3]. As the materials Roberts uses are ‘malleable and ever-changing,’ they successfully convey how queer worldmaking is always ‘fragile’ and certainly ‘ephemeral’. (Fountain & Roberts 2020; Berlant & Warner 1998: 561)

Sarah Schulman’s ground-breaking book The Gentrification of the Mind (2012) charts the process of intense gentrification that New York faced during the years 1981 to 1996, when the AIDS epidemic swept through the City. She names the most gentrified neighbourhoods in Manhattan (East Village, West Village, the Lower East Side, Harlem, and Chelsea) and compares them to the findings of a report on the social impact of AIDS published in 1993 by the National Research Council, which recorded that Manhattan’s highest rates of infection were also in these areas. The horrific reality was that AIDS-related deaths meant that there was a drastic turnover of apartments, particularly given that fact that people’s partners or kin often had no legal right to these residences. Rebellious queer culture and a vibrant underground arts scene was decimated—apartments were simply sold off and replaced by a predominantly white, middle-class cohort. This is an important point to make, as for Schulman gentrification has a dual referent. While she posits that gentrification is a literal ‘concrete replacement process’ in which communities are displaced, she also suggests that it is simultaneously a process of spiritual gentrification, an ‘internal replacement that alienated people from the concrete process of social and artistic change’. (Schulman 2012: 14) Many members of the LGBTQ+ community therefore flocked toward cheaper areas of inner cities, such as Williamsburg in Brooklyn which had cheaper rents and an emerging queer culture. Although this did give rise to new opportunities for social and cultural connectivity, scholars such as Goldstein (2018) have written first-hand accounts that demonstrate how gentrification is still rife within these neighbourhoods in Brooklyn, causing an increasing divide between social classes, and posing a threat to many queer communities. The queer world must therefore be thought of as a transient space which is not locatable by a fixed concept of ‘home.’ It is a space made up of ‘entrances, exits, unsystematised lines of acquaintance, projected horizons, typifying examples, alternate routes, blockages, [and] incommensurate geographies’. (Berlant & Warner 1998: 558)

At the time of writing, Roberts is finishing an ongoing large-scale piece entitled VanDykesTransDykesTransVanTransGrandmxDykesTransAmDentalDamDamn, which began in 2013. (Fig.7) They describe the work as a ‘fiber collage of a post-apocalyptic speculative conversion van’. (Roberts n.d.) It particularly evolved as part of a Studio Views: Craft in the Expanded Field residency at the Museum of Art and Design in New York in 2017. The work extends similar themes around the transitory nature of queer spaces, by continuing to ruminate on both the promises and problems of queer and alternative kinship structures. Within the work, Roberts pays homage to pioneering lesbian, queer, and transgender histories and themes of nomadism, landlessness, movement, and identity, by drawing influence from so-called conversion van culture. (Roberts n.d.) Alongside their colourful use of fiber, Roberts also uses materials such as shoelaces, leather, zippers, and metal studs, as a nod towards the iconography associated with these queer subcultures: just as the vans can be customised, so can we. The work was inspired by a 2009 article by Ariel Levy which appeared in The New Yorker, and discussed the Van Dykes: a lesbian ‘van gang’ that traversed North America in the late 1970s. (Roberts n.d.; Levy 2009) The Van Dykes were founded by Heather Elizabeth and Ange Spalding in 1977, and quickly grew to become a much larger collective of lesbian separatists and non-monogamous women, all of whom took on the surname Van Dyke. (Levy 2009) Living life together on the road, the group were totally ‘devoted to living in an alternate, penisless reality,’ and would only stop at outposts of Women’s Land over the United States and Canada. (Levy 2009) These were places that were owned by women, and where only women would be welcome—so much so that they were more commonly referred to as ‘wimmin’s land’ or ‘womyns land’ in an attempt to ‘keep men out of their words as well as their worlds’. (Levy 2009) As Levy (2009) notes, their attitude was: ‘Why capitulate, why compromise, when you could separate, live in a world of your own invention?’

These traditions still continue today, but are far less separatist, with other queer and gender-non-conforming individuals reviving the transient and creative culture of these van gangs to craft more inclusive and communal travelling kinships. As Roberts states, despite drawing influence from these cultures of worldmaking it is ‘important to remember that “feminist” spaces can create margins, whether [they are] excluding trans people or people of colour’. (Saint Thomas 2017) Examples of contemporary van gangs are documented in zines such as Vanifesto, produced by Damien Luxe, which even contains an instructional guide and a list of recommendations of places to purchase vans and suggested DIY (do-it-yourself) customisations such as ‘exxxtra plush seating’ for the bed-cum-bench area. (Luxe 2011: 18) The culture has extended far beyond just a process of inhabiting otherwise, but has become an entire way of life and an artform in itself. For example, the Heels on Wheels Glitter Roadshow is a ‘dazzling cabaret of performance art works by queer folks on femme/inine spectrum genders’ that tours the United States annually to re-vision ideas of what ‘thriving and surviving as femme folks can be’. (Luxe, Ács & Ibarrola 2015: 19) Roberts therefore both celebrates the queer-feminist legacy of nomadic worldmaking, and also considers its current relevance to communities who have also had to use resourcefulness and imagination to craft alternative ways of living and being.

In short, Roberts’ experience in the world ‘requires flexibility, adaptability, resilience, and resourcefulness,’ and this is reflected at the very level of their material choices which are accessible, portable, and move nimbly between class structures. (Fountain & Roberts 2020) Their work serves as an important reminder of the role that crafting has for many members of the queer community—beyond heteronormative and cisnormative concepts of home and family. In addition to the role of crafting spaces and communities, which Roberts’ work exemplifies, Berlant and Warner (1998: 558) also highlight how making a queer world has required the ‘development of kinds of intimacy that bear no necessary relation to domestic space, to kinship, to the couple form, to property, or to the nation.’ Moving on from a focus on worldmaking and community building, this article will now turn towards other forms of worldmaking that Berlant and Warner highlight—namely the crafting of intimacy and sexual cultures.

Jesse Harrod

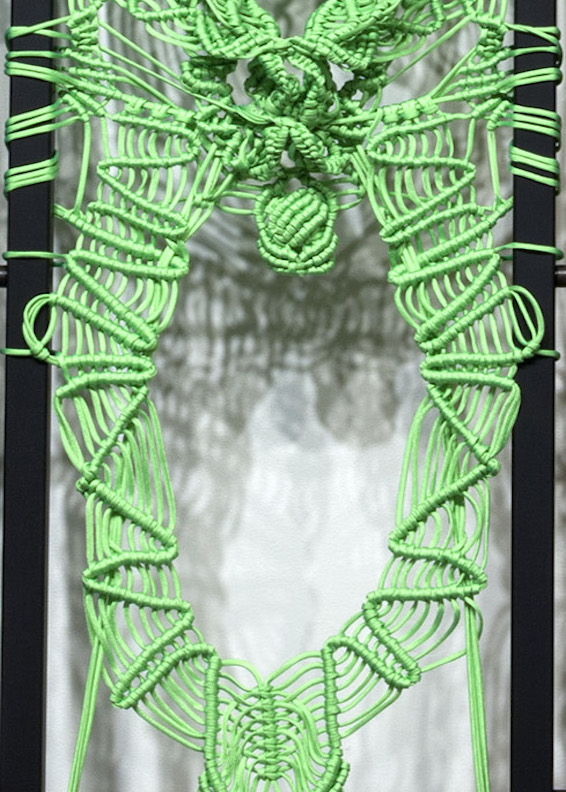

Much like Roberts, Jesse Harrod also states: ‘[t]he politics of cloth seem inescapable, and material and technical histories are fundamental to my choices as a maker … [t]he materials are stand-ins for political ideas, for people, for moments, for gender expressions’. (Chaich & Oldham 2017: 140) Much of Harrod’s work is dominated by abstracted phallic and labial forms which droop, sag, hang and unfold in the spaces in which they are exhibited as a result of their imaginative suspension systems. Sculptures such as the Pensile Arrangement series (2013) explore the sexual prosthetics of queer and lesbian sexuality through the malleability of phallic and labial forms. Although they are ‘well hung’ from the ceiling, the inclusion of steel frames and cock rings, which the supports are attached to, mean that the sculptures take on a more intermediate state within the space; they are simultaneously flaccid and erect in mid-air. (Fig.8) The references to strap-on harnesses, sex swings, cock rings and fetish objects are all part of what Berlant and Warner (1998: 558) would describe as the ‘inventiveness of queer world making’ in relation to queer sexual culture. Despite these important points of reference, much of Harrod’s work does not bear overt references to physical anatomy. Instead, it stages a series of encounters and personal interpretations that exploit the register of cloth to allude to bodily organisms and sexual practices. This is perhaps most notable in Harrod’s Rangers series (2014-), which consists of individual welded frames that are covered in decorative macramé. They are then assembled together in a large-scale modular installation that creates a wall of leaning ‘bodies’. (Fig.9) The series started in 2014, but the artist revealed that they see it as ongoing; continuing to take new forms, variations and personalities that assert non-normative ways of being and loving.

The Rangers are created following traditional macramé techniques involving processes of hitching, but they are made from netted parachute cord (more commonly known as paracord) instead of traditional materials such as hemp rope or jute. Macramé—a decorative off-loom technique of lateral knotting which dates back to Babylonian times—became incredibly popular in the 1970s (particularly in Britain and America), and was mainly used for creating household and functional objects such as hanging planters, lampshades, and hammocks. (Auther 2008: 24) It later established a very specific stereotype as something ‘hippie’ or ‘homespun’ associated with the period. (Auther 2008: 24) The macramé hobby craze was problematic for the fiber movement because it reinforced assumptions about fiber as a women’s medium, of ‘low’ art status, and as a domestic hobby. (Auther 2008: 25) For Harrod though, macramé and its associations offer further opportunities for exploring different ‘relationships between the medium and other cultural developments of the period, like psychedelic music, glam rock, altered states of consciousness, and shifting ideas about dress and gender-identity/presentation’. (Orendorff 2017: 15) Rather than refuting macramé’s hobbyist associations, Harrod exploits macramé’s links to do-it-yourself cultures in order to explore how for queer-feminists, the crafting of worlds, identities and cultures is also a do-it-yourself practice.

Paracord is a utilitarian nylon rope which was originally used as a suspension line for military parachutes during World War Two. (Paracord Galaxy n.d.) It now has a wide range of uses but it is primarily used for activities like climbing and camping—all survivalist practices. More importantly, the use of hitched rope also evokes associations of strap-on harnesses and BDSM practices. While more natural materials such as hemp or jute rope are traditionally used in the bondage community, blogs such as Lovesense (n.d.) suggest that paracord might now be a more favourable material due to its versatility, durability, and the fact that it is less likely to cause skin irritation. Because of its use in military operations, paracord would mainly have been made in military approved colours such as olive green, brown, black and beige; but here Harrod queers the use of paracord, using fluorescent and garish colours for decorative effect. Harrod claims a maximalist aesthetic for their work, which is a term often used to describe forms of artistic production that celebrate richness, excess and decoration—terms that have commonly been used to reinforce the ‘lowness’ of craft in the cultural hierarchy. In relation to their work, Harrod explains that ‘maximalism is about conveying, through an abundant use of colourful materials, the enormity and messiness of feeling in the face of political structures that oppress marginalised people, particularly queer and transgender people’. (Harrod 2017: 33) This extends from Harrod’s own experience of living in rural Virginia, which was a particularly challenging environment because, they recall, ‘feminism, queerness, and diversity were challenging notions for many in my midst’. (Salomone 2017) Harrod therefore works from a personal place exploring their own subjectivities—‘the personal is political, right?’—but simultaneously wants us to think about second-wave feminism within a contemporary context that is inclusive. (Chaich & Oldham 2017: 140) The maximalist aesthetic helps to employ a direct form of address: ‘I want my installations to scream at you much like the proto-typical 1970s militant feminist screams at you!’. (Harrod 2017: 33) Harrod notes that while they borrow aesthetic components from their mother’s generation of feminism, they fuse this with current reference points and practices of queer intersectional feminism in order to build a bridge between the two. (Salomone 2017) ‘Formally speaking, playing with scale, color, and materials can connect macramé to the present, while remaining in conversation with the aesthetics of formative feminist art,’ they explain. (Salomone 2017. Their work is therefore ‘tied up,’ quite literally, ‘not just with the important work of political defiance and critique, but also with visualising and inhabiting otherwise’ (Getsy 2016: 15)

Eight of these Rangers were exhibited during Harrod’s solo show Low Ropes Course, which took place at NurtureArt in Brooklyn from 12th September to 11th October 2015. The latter portion of the exhibition title is a play on a type of team-building course that consists of a series of obstacles designed to challenge the participants’ resilience, and the reference to a ‘low’ course hints towards fiber as a particularly ‘low’ form of making. (Sorkin 2017: 61–62) In this exhibition, five of the sculptures leaned against a wall together like a clique of friends, mid-conversation, while two were coupled together as if sneaking off on their own. Another is left separated and alone, possibly acting as voyeur. Each of the eight pieces in the series feature components that allow them to connect or stack in a variety of ways. The ways in which they can be moved, coupled, or separated therefore aids in this activation of their forms as ‘bodily’ objects. Their groupings and couplings (or subsequent de-groupings and un-couplings) are decided by Harrod as reactions to the site in which they are installed, as a result of experimental play. (Orendorff 2017: 15) Much like human relationships, the connections can break apart, or they can be pieced back together. In this sense, the forms become stand-ins for human lives, and operate as queer kin for Harrod. Harrod explains: ‘I am building or creating a fictional community given that I have moved so much and don’t have a strong community in my daily life’. (Samson & Harrod 2017: 112)

The process of macramé also allows the artist to construct particular shapes through the use of negative space. This is exploited here, as Harrod uses hitches in a very open spread, resulting in a series of orifice-like forms that infuse their seemingly innocent content with direct references to anatomy. Harrod’s artistic practice usually splices bodies apart; they usually take inspiration from a particular limb or organ and work on abstracting its form. However, in the Rangers series we have full sized bodies which are actually sized to Harrod’s own height and width, with the orifice-like areas lining up with the position of their own genitalia. (Chaich & Oldham 2017: 140) Some provoke more overt anatomical forms, such as when the more close-knit and built-up hitching forms 3D structures, which, in the case of one of the sculptures, does appear rather clitoral. (Fig.10) Despite this, Harrod suggests that the works actually draw more upon plant morphologies to ‘explore ideas of sexual growth, pollination and the perversity of natural forms,’ than they do human biology. (Harrod, n.d.) Other elements of the series are certainly much more ambiguous; simply forming many open-work structures that do indeed look more like the veiny structure on the surface of a leaf than any human anatomy. (Fig.11) While the physicality and three-dimensionality of Harrod’s sculptures often provoke associations with bodily relations, the Rangers do not directly imagine the human. Rather, queer capacities are engendered by what art historian David Getsy (2017: 254) calls the ‘activating’ of relations … between forms, against an opposition or context, or (in the case of complex forms) among the internal dynamics of their components.’ Harrod’s use of paracord is therefore particularly relevant for exploring these notions of the sexed body, but it allows for the representation of a greater range of gender identities whereby the forms are not easily readable as a particular gender. This form of bodily abstraction therefore seems to produce ‘less determined and more open ways of accounting for bodies and persons’. (Getsy 2015: xii)

Despite the fact that this article has referred to Harrod’s Rangers as ‘sculptures,’ the artist explains that they actually see the works as ‘drag performers’. (Harrod 2017: 34) As they put it, ‘like these drag acts who used thread and cloth to create their own communities and worlds, I view my works as themselves members of a dynamic queer community’. (Harrod 2017: 34) The metal bases form a supporting structure, or solid body, but the macramé and more decorative embellishments masquerade on the surface, functioning much like the use of clothing or make-up. Furthermore, the references to bondage and harnesses remind the viewer that such ‘decoration’ is not merely superfluous, but rather functions as a particular signal for what Harrod describes as ‘other ways of being, knowing and relating’. (Harrod 2017: 34) These notions of support are perhaps more obvious in a series of small pride floats Harrod began creating in 2013, simply titled Floats. At the time, Harrod was living in Chicago, and recalls the ‘humorous and tragic’ sight of a string of empty floats outside their window at around 6AM in the morning, as if waiting to be ‘activated’ by the queer performers. (Harrod 2017: 33) Harrod notes: ‘what struck me most of all was that these floats were the hidden and unacknowledged material support for the performance; they were what, in the end, would make the unfolding of a queer community possible’. (Harrod 2017: 33) Each of the floats are also named after a particular icon who has formed an important part of identification for Harrod—such as poet Eileen Myles, rock-star Suzi Quatro and writer Judy Blume. (Fig.12) Through their work, they therefore make visible the often-invisible effects of material support that are essential for queer-feminist survival. In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009) José Esteban Muñoz considers the idea of queerness as a ‘stage,’ playing on both the ways in which parents with queer children often delusionally cast their child’s queerness as a ‘stage,’ as well as the role of the physical stage in places such as gay bars and independent rock clubs. In a particular paragraph about one of Kevin McCarty’s photographs of a stage at LA’s Silver Lake Lounge, Muñoz mentions how ‘messy drag queens perform their crafts’ under the white neon sign that reads ‘Salvation’. (Muñoz 2009: 108) Muñoz seems to provide a nod towards the role of drag-as-craft here, but the word ‘salvation’ particularly resonates with the transformative powers of nightlife that queers, and particularly queers of colour, have always flocked to for a sense of community and culture. (Muñoz 2009: 108) In a similar vein, Harrod’s small empty floats seem to express notions of the staged self and make visible the support structures that enable queer individuals to rise up, to congregate, to float. Moreover, their emptiness depicts a certain degree of potentiality which, as Muñoz suggests, ‘is always in the horizon and, like performance, never completely disappears but, instead, lingers and serves as a conduit for knowing and feeling other people’. (2009: 113)

Bringing the Threads Together

One of the key similarities in the work of both Roberts and Harrod is the ways in which they draw influence from 1970s culture and second wave feminism. This is perhaps most evident in Roberts’ VanDykes, which takes inspiration from lesbian ‘van gang’ culture, and Harrod’s Rangers series which draws on both traditional macramé techniques associated with the period, as well as its sexual revolution. Yet, while these forms of crafting might certainly be seen to represent a nostalgia for the past, both of these artists seem to craft a new set of feminist intellectual politics that is not separatist, but is inclusive of the present-day queer experience. Roberts achieves this by drawing inspiration from more contemporary and inclusive ‘van gangs’ in order to offer up a glimpse into what a potential postapocalyptic, nomadic, queer community might look like. Harrod, on the other hand, queers the use of traditional macramé processes to demonstrate the do-it-yourself nature of queer, particularly lesbian, sexual cultures, while also offering up queer imaginations of the body that do not conform to either human or plant morphologies. Through these strategies, both artists affirm the importance that craft(ing) has for surviving in a world ‘inimical to one’s own survival’.(Cvetkovich 2012: 34)

Just as this article has woven together an eclectic array of references, it is also worth noting how Roberts and Harrods also draw inspiration from a range of sources—from queer communal living, the AIDS Quilt, lesbian van gangs, BDSM sexual cultures, and drag performers respectively. This not only highlights the multifaceted use of craft in queer culture, but it also demonstrates the ways in which queer subjectivities are often formed out of an eclectic array of (sub)cultural references and reworkings of dominant cultural representations. This seems to be echoed by much of their work featured here—particularly in Roberts’ The Queer Houses of Brooklyn and in Harrod’s Rangers and Floats. All three works seem to illustrate the particular importance of support structures in enabling queer-feminist survival. They do so by making visible the often invisible. Roberts plots a map of queer communal houses in Brooklyn to show their existence and draw attention to issues of gentrification. Harrod uses metal bases in Rangers and the symbol of empty stages in Floats as powerful metaphors and mediations on supporting structures. Through their processes of ‘queer handmaking,’ the artists seem to emphasise that those who have previously been denied a world and communities of support can, quite literally, craft one into being. (Bryan-Wilson 2017: 40)

In short, Roberts and Harrod illustrate the do-it-yourself nature of queer worldmaking, with Roberts’ work primarily conveying the literal crafting of kinship structures, and Harrod’s the inventiveness of queer sexual cultures. Both, however, seem to convey the support systems needed for queer-feminist survival to even to take place for an ‘unfolding of a queer community’ to become possible. (Harrod 2017: 33) Through an analysis of their work, this article has demonstrated that craft, or more broadly the notion of crafting, is an essential strategy for living and loving ‘otherwise.’ It is hoped that many more scholars will pick up the threads that have been laid out here, allowing us to continue braiding together the three strands of gender, sexuality, and art in future craft scholarship.

Notes

[1] Hammond attempted to curate an earlier show titled ‘Lesbian Art Show’ in 1978 at the 112 Greene Street Workshop in New York, but many artists were anxious about showing their work in a lesbian framework. Writing in the Encyclopaedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures, Harmony Hammond (2000a: 64–65) also recalled that aside from the exhibitors being female and lesbian, the 1980 GALAS show was particularly noteworthy for the way in which it ‘marked the first time that lesbians of color participated in a major exhibition of lesbian art,’ which were the African American artist, Lula Mae Blocton, and Cuban-American artist Gloria Longval.

[2] Although it was primarily used to mark homosexual men, it is widely suggested that this category would extend to a wide range of individuals whose sexuality and gender identity was deemed ‘deviant’ by these forces, particularly bisexuals and transgender men. Earlier, homosexual male prisoners were identified with either: a green triangle (criminals), red triangle (political prisoners), the number 175 (referring to Paragraph 175, the section of the German penal code criminalising homosexual activity), or the letter A (which stood for Arschficker, literally ‘ass fucker’).

[3] The relations between queerness and sloppy craft are not my primary focus here, but for more on this see: McBrinn, Joseph (2015), “‘Male Trouble’: Sewing, amateurism, and gender”, in Elaine Cheasley Paterson and Susan Surette (eds), Sloppy Craft: Postdisciplinarity and the Crafts, London: Bloomsbury, pp.27–44; Auther, Elissa and Elyse Speaks (2015), ‘Sloppy craft as temporal drag in the work of Josh Faught,’ in Elaine Cheasley Paterson and Susan Surette (eds), Sloppy Craft: Postdisciplinarity and the Crafts, London: Bloomsbury, pp.45–59.

Acknowledgements

To LJ Roberts and Jesse Harrod—for creating such important work and for their time in answering my questions. Thanks to Professor Hilary Robinson and Dr Mo White for their comments on earlier versions of this work, which extended from my practice-led PhD research. Lastly, to the editors and reviewers at MAI, for helping to craft such an important home for intersectional scholarship relating to feminism and visual culture.

REFERENCES

Adamson, Glenn (2007), Thinking Through Craft, Oxford: Berg.

AIDS Quilt, ‘The AIDS Memorial Quilt,’ https://www.aidsquilt.org/about/the-aids-memorial-quilt (last accessed 25 June 2020).

Auther, Elissa (2010), String, Felt, Thread: The Heirachy of Art and Craft in American Art, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Auther, Elissa & Elyse Speaks (2015), ‘Sloppy craft as temporal drag in the work of Josh Faught,’ in Elaine Cheasley Paterson and Susan Surette (eds), Sloppy Craft: Postdisciplinarity and the Crafts, London: Bloomsbury, pp.45-59.

Berlant, Lauren & Michael Warner (1998), ‘Sex in Public,’ Critical Inquiry, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Winter 1998), pp.547–566.

Bowdoin College (2016), L.J. Roberts: ‘Queer Strategies, Queer Tactics,’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8b4663x30A&t=581s (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Brighton Museum, ‘The Museum of Transology,’ https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/brighton/exhibitions-displays/brighton-museum-past-exhibitions/past-exhibitions-2019/the-museum-of-transology/ (last accessed 27 June 2020).

Bryan-Wilson, Julia (2017), Fray: Art and Textile Politics, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chaich, John (2014), ‘Queer Threads,’ Queer Threads Catalog, 23 January 2014, p.3-4, https://issuu.com/leslielohmanmuseum/docs/queerthreadscatalogue_final (last accessed 7 June 2020).

Chaich, John, and Todd Oldham (2017), Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community, Korea: AMMO Books.

Cvetkovich, Ann (2012), Depression: A Public Feeling, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Fountain, Daniel & LJ Roberts (2020), ‘LJ Roberts’ Queer Epics,’ Decorating Dissidence, https://decoratingdissidence.com/2020/04/03/lj-roberts-queer-craft-epics/ (last accessed 3 June 2020).

Gander, Kashmira (2017), Museum of Transology: The Exhibition of Everyday Objects that are Extraordinary for Trans People,’ The Independent, Wednesday 25 January 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/museum-transology-trans-people-lgbt-exhibition-london-college-fashion-objects-gender-sexuality-a7543781.html (last accessed 27 June 2020).

Getsy, David (2015), Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in The Expanded Field of Gender, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Getsy, David (2016), Queer, London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Getsy, David (2017), ‘Queer Relations,’ ASAP/Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, (May 2017), pp.254-257.

Goldstein, Katie (2018), ‘Queer Homes in a Non-Queer World’ in Elizabeth McNeil, James E.Wermers, and Joshua O.Lunn (eds), Mapping Queer Space(s) of Praxis and Pedagogy, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.269–278.

Hammond, Harmony (2000a), ‘Art, Contemporary North American,’ in Bonnie Zimmerman and George E. Haggerty (eds), Encyclopaedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures, New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc, pp.63–66.

Hammond, Harmony (2000b), Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History, New York: Rizzoli.

Harrod, Jesse (2017), ‘Militant Cloth’ in Jesse Harrod, Low Ropes Course, Rotterdam: Publication Studio, pp.32–34.

Harrod, Jesse (n.d.), Rangers, http://jesseharrod.com/rangers/ (last accessed 28 June 2020).

Hawkins, Peter S. (1993), ‘Naming Names: The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt,’ Critical Inquiry, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Summer, 1993), pp. 752-779.

Jones, Cleve (2000), The Making of an Activist: Stitching a Revolution, New York: Harper Collins.

Katz-Frieman, Tami (2008), ‘Craftsmen in the Factory of Images,’ in Boys Craft, Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art.

Levy, Ariel (2009), ‘Lesbian Nation,’ The New Yorker, February 23 2009, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/03/02/lesbian-nation (last accessed 28 June 2020).

Lovesense (n.d.), Bondage Rope 101 – 12 Useful Tips And Extensive Rope Rundown, https://www.lovense.com/bdsm-blog/bondage-rope (last accessed 28 June 2020).

Luxe, Damien, (2011) Vanifesto: A Mediation on Van Lust, http://www.damienluxe.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/VANIFESTO_final.pdf, (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Luxe, Damien, Heather María Ács, Sabina Ibarrola (2015), Glitter & Grit: Queer Performance From the Heels on Wheels Femme Galaxy, Portland: Publication Studio.

McBrinn, Joseph (2015), “‘Male Trouble’: Sewing, amateurism, and gender”, in Elaine Cheasley Paterson and Susan Surette (eds), Sloppy Craft: Postdisciplinarity and the Crafts, London: Bloomsbury, pp.27–44

Muñoz, José Esteban (2009), Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York: New York University Press.

O’Hanian, Hunter (2014), ‘Greetings,’ Queer Threads Catalog, 23 January 2014, p.2, https://issuu.com/leslielohmanmuseum/docs/queerthreadscatalogue_final (last accessed 7 June 2020).

Orendorff, Danny (2017), ‘Introduction: Best Friends,’ in Jesse Harrod, Low Ropes Course, Rotterdam: Publication Studio, pp.12-15.

Paracord Galaxy (n.d.), What is 550 Paracord, https://paracordgalaxy.com/content/8-what-is-550-paracord-parachute-cord-550-cord (last accessed 28 June 2020).

Parker, Rozsika (1984), The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, London and New York: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd.

Reed, Christopher (2011), Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Risatti, Howard (2007), A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

Roberts, LJ (n.d.), Studio Views @ MAD, http://ljroberts.net/index.php?/work/studio-views-craft-and-the-expanded-field/ (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Saint Thomas, Sophie (2017), ‘Artists Sarah Zapata and LJ Roberts Use Textiles to Express Their Identities,’ Allure, September 13 2007, https://www.allure.com/story/queer-artists-exhibition-museum-of-arts-and-design (last accessed 28 June 2020).

Salomone, Andrew (2017), ‘“Knotty” Macramé Works Bind Feminism, Queerness, And Diversity,’ Vice, 11 March 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/pgwkqz/knotty-macrame-works-bind-feminism-queerness-and-diversity (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Samson, JD &Jesse Harrod, ‘Interview,’ in Jesse Harrod, Low Ropes Course, Rotterdam: Publication Studio, pp.108-19.

Schulman, Sarah (2012), The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, 40 Under 40: L.J.Roberts, 8 June 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YxnyPQ7YATg&feature=emb_title (last accessed 4 June 2020).

Sorkin, Jenni, ‘Material Bodies,’ in Jesse Harrod, Low Ropes Course, Rotterdam: Publication Studio, pp.60-63.

Thompson, Margo Hobbs (2010), ‘DIY Identity Kit: The Great American Lesbian Art Show,’ Journal of Lesbian Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2-3, pp.260-282.

Tsjeng, Zing (2017), ‘The Museum of Everyday Objects That Makes Transgender Lives Visible,’ Vice, January 16 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/gyxg34/museum-of-transology-ej-scott-curator-interview (last accessed 26 June 2020).

Tucker, Marcia (1996), A Labor of Love, New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey