‘Surface: Skin & Scab—Porous Virality:’ An Interview with Claudia Bitrán

by: Rebecca Shapass , June 25, 2022

by: Rebecca Shapass , June 25, 2022

Claudia Bitrán works primarily in painting and video, frequently using DIY aesthetics to represent the hyperbolic worlds of social media and pop culture. The artist employs a wide range of painting strategies to metamorphosise her source material, resulting in dense and thick surfaces that transform the content of the artist’s videos. She holds an MFA in Painting from Rhode Island School of Design (2013), a BFA from the Universidad Catolica de Chile (2009), and was recently an artist-in-residence at Pioneer Works, New York. Bitrán teaches painting at Sarah Lawerence College, Pratt Institute, and Rhode Island School of Design. She lives and works in Brooklyn.

Her work can be viewed at https://www.claudiabitran.com/ and on Instagram @claudiabitran

*

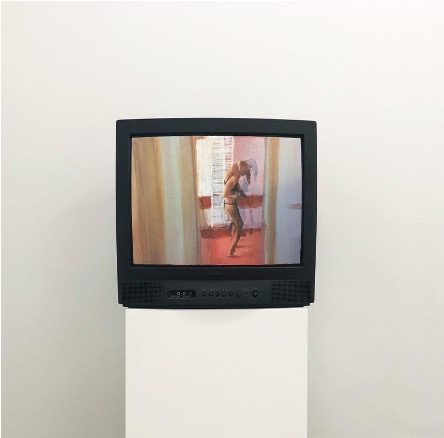

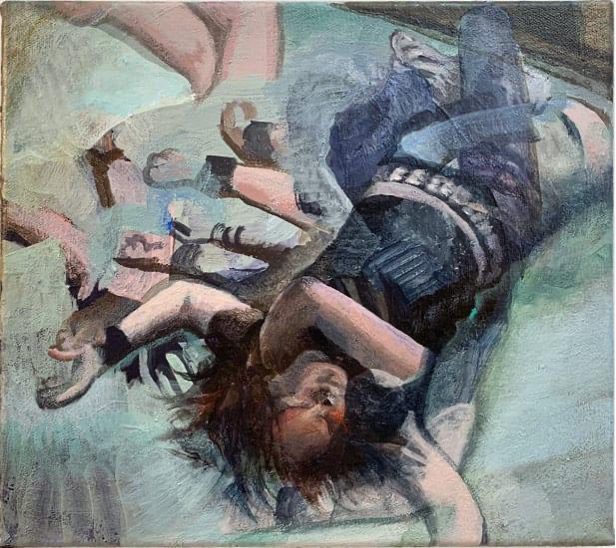

In 2019, Claudia Bitrán arrived at my studio to borrow a few CRT monitors for an exhibition she was installing at Cindy Rucker Gallery. We had been connected through Smack Mellon, where I was currently a resident in the exact studio Claudia once inhabited. The exhibition she was preparing for was called Fallen, and it included Claudia’s first series of stop-motion painting-animations that depict videos of inebriated bodies in various states of reverie or decay. The videos—equally specific and anonymous—were carefully curated by Bitrán through social media browsing, and then meticulously re-animated as she painted frames atop frames on a single canvas, and photographed them to create short, stop-motion animations.

I continued to follow Claudia’s work over the next few years, witnessing her wrestle with the vernacular of virality in both Frenzy (2020) and Be Drunk (2021), where her transmutation of ‘disaster videos’ probe the fragility of our own mortality through the pursuit of reckless euphoria. Throughout these series, Bitrán’s subjects went from playfully intoxicated to teetering on the edge. Her selection of visuals—a glowing meteorite tenderly tracing an arc on screen before presumably landing in an unseen mess of fiery ruin, a drunken teen doing cartwheels and kicking her friend in the face—propel an audience to a place between humour and ruin. She creates curiosity where repulsion may take the lead, rendering scenes of vomit as multi-colour, impressionistic waterfalls from the mouth, inviting the audience to sit with what might be seen as one of a million viral videos within a lengthy social media scroll.

With Claudia’s work, I always find myself compelled by a push and pull; she has a knack for pointing to media moments that breed consumption both ways: the viewer consumes the image, and the image consumes the viewers. This is a consistent theme in her oeuvre, which has, over the course of a decade, often engaged with iconic media from films such as Titanic to the music videos of Britney Spears. However, Claudia engages with her scavenged material with a sense of tender awareness of her role as an additional disseminator, a filter, and vessel of transformation for these images. In her most recent show, Stereotypies, at Cristin Tierney Gallery, fragments of Be Drunk and new watercolor animations collide with Bitrán’s ongoing engagement with Britney Spears. The combination, though uncanny, results in a timely two-way mirror. Though Britney is easily identified amongst the otherwise anonymous subjects, Bitrán raises a question about viewership. As Bitrán abstracts recycled media, she offers a space of doubt. Pushing beyond the real, Bitrán approaches these viral documents as opportunities for active engagement: ways to advance beyond the digital skin and interrogate the images of our consumption.

*

Rebecca Shapass (RS): Your recent show, Stereotypies brought together three different bodies of work through the lens of compulsive repetition. This is, of course, performed by the work—videos that repeat in endless, short loops—but it is also performed by you as you make the works. For me, the word ‘stereotypies’ also evokes an image of the sort of repetitive scrolling and clicking one does while encountering media online. Can you talk about your process, and how it informs the work and vice versa?

Claudia Bitran (CB): For the majority of us, compulsive scrolling is both a soothing action and a useless one, that ultimately weakens the soul and alienates us from the tangible world. It is through compulsive scrolling that I find the subjects for my paintings. From the very beginning of the process of animating, I am torn between the pleasure that I feel in consuming viral images of Britney Spears’ face, people vomiting, animals behaving erratically and the guilt of knowing that there are serious atrocities happening in the world, and these images can be seen as distractions. Nevertheless, I see these videos as symptoms and/or backlashes of larger atrocities. I see memes, gifs, and fails, as examples of an underlying malaise; they act as comic relief—morphine for the pain. Yes, to scroll unstoppably through these videos is an escapist ritual; however, I need a bit of comic relief. As I scroll, I collect videos and photos that get added to my extensive archive which houses an array of epic fails and a thousand close-ups of Britney’s face. The process of animating these videos makes me aware of my superficial consumption. By painting each frame, I feel like a participant and not just a passive scroller. Painting every frame helps me to connect with what’s actually going on under these videos. It’s like getting to rediscover them through re-performing them.

RS: The quality of under-ness occurs doubly in these works. While your painting-animations allow the viewer to see all the successive frames contained beneath the final static frame on the canvas, the paintings bear only the final image of the animation. These works seem to vibrate with traces of movement and residue from the previous frames present—a seepage of under-ness, if you will. I am thinking about this in relation to how images live online, and also how they live in the mind/body?

CB: Through animating bodies frame after frame, I want to make the subjects that I represent travel through different pictorial worlds. I try to employ as many painting moves as I can when animating: mark-making styles, gestures, different uses of line, naturalistic to graphic uses of colour and shapes, diverse levels of rendering, speeds, pressures. I like to make my subjects become cartoons, hyperreal, cubist, graphic, abstract expressionist throughout the duration of the videos. In some videos I vary more than others. Sometimes I try to impersonate specific painters.

The stasis lasts ¼ of a second in the video, but I know that the viewer is able to identify all of these registers whether consciously … or subconsciously. I try to put much attention to every single frame and have them be as specific as I can, in order to inject narrative tangents and explorations within the predictable and dehumanising and homogenising nature of virality. I see the final paintings as the remains of all that just happened. Like fossilised mayhem.

The images I work with are of fast consumption and fast forgetting, but they will never be erased from the internet. They will infinitely exist as attachments, as pixelated, overshared residues of their short lived virality. I think of these files as dust particles floating around our popular digital landscape; they are light and scattered, innocent comic dust, they bring you a smile, a brief entertaining endorphin release, and then keep floating. But if we could recollect all of the dust particles of the image of Britney’s shaved-head episode—if we were able to gather all of those files, memes, gifs, all the photoshopped bully and fan art, paparazzi photos … if we could collect all of that ‘dust’ it would probably add up to the size of a nuclear plant.

RS: Yes, this idea of what takes up space is relevant, right? Because the Baudelaire poem that the Be Drunk series references, speaks to a sort of emptying of self—a freeing of the self to make room for the throes of life.

You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it—it’s the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk.

But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk.

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . .ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: ‘It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.’

(From Charles Baudelaire, ‘Be Drunk’)

RS: For this reason, I am intrigued and exhilarated by the cohabitation of Baudelaire and Britney. Baudelaire’s poem speaks to a sense of exuberance & resilience. I think Britney’s—dare I say—hero’s journey embodies the ethos of his writing. Where do you see dissonance or resonance between the two?

CB: In our initial conversations the gallery had expressed enthusiasm in exhibiting both my recent Britney portraits and my Be Drunk series (in which animals and mostly female teenagers are falling and getting hurt). I felt like the conversation between these two works poignantly addressed ongoing online aggression towards women in vulnerable states. However, I still felt that I needed to give agency to the subjects by creating a bridge between the two works, so that the content could expand into a broader conversation that would complicate the subject beyond criticising the consumption of these images as an act of violence.

The videos Britney posted of herself on Instagram dancing in her living room during the last year of her conservatorship were a perfect embodiment of that agency and control despite entrapment. After all, her freedom was achieved through her persistent and eclectic use of social media. Her posts were, and still are, described as bisarre, delirious, erratic, too confessional, scary. I saw the posts of her dancing, specifically her twirling, as a metaphor for her capacity to connect to her performance on a deep uncensored level—to not give a shit, to heal, to be expressive and escape.

When I saw the gallery, I realised it looked a little bit like a ballet studio: bright light, clean wooden floor, and I thought it could be a good place to make Britney dance. Coincidentally, both Britney’s living room and the gallery space have these long windows in the back, which I used as a formal frame for Britney Twirling—the video playing in the centre of the gallery—mirroring the windows of Britney’s home within the gallery space.

The final work included in the show is much more direct, and addresses the prison of repetition from a less mediated perspective. It is a watercolour animation of Gus, the polar bear who lived in the Central Park Zoo for over twenty years. People used to call him ‘the neurotic polar bear.’ It is likely that his repetitive swimming pattern made his captivity less paralysing. This animation is located in between the Be Drunk Series, at the left of The Britney Twirling animation. The show comes together: Britney, polar bear, erratic animals, drunk people falling. In ways, they are all still being watched and pitied in the context of the gallery, as they may have been online. However, when I re-share these images as painting animations, I present my subjects’ repetitive tics as glorious choreographies, reframing the ‘throw away’ image with newfound dignity and attention (my own and the viewers’).

RS: Of the many images of Britney in the digital sphere, your Britney works take on a new meaning when contextualised with other viral images—images of non-celebrities, people in their daily lives. I am fascinated by how Britney has re-emerged in your practice through the spaces of virality that you have been exploring. Britney is ‘viral’ in so many ways—her music has touched so many, and her fans are devoted. On the flip side, her public-facing life has potentially negatively impacted her own experience at times while simultaneously propelling her virality to new levels.

CB: I am often asked how I feel about using Britney’s image to create my work: Don’t you think that she’s been over exploited enough? Why do you engage in this system that uses her image over and over again? Are you capitalising on her image? [These are questions] that I have asked myself during these 15 years of making work about Britney—from performing as an impersonator of her on TV, remaking her videos, participating in the Britney Spears Dance challenge, and now when creating paintings and watercolours of her public presence. The answer is: No, my work is a homage. I don’t think that it is harmful to show her image one more time, because the way that I am doing it adds complexity to the image. I am inspired by her. I am digesting and rewriting her work through a labor-intensive, involved processes full of affect. Of course, I use humour, but I use humour [as] a nervous laugh—a cathartic tool to convince viewers that she’s not the crazy one. In my process, I slow down her videos and take a closer look at each one of her steps, her expressions, her versatile power, her radical joy, and sexuality. If anything, these are not harmful depictions of Britney. I create these to fix what’s already out there.

RS: Your subjects (celebrity, human, and animal) all occupy the same surface, whether this occupation be at the origin—on your phone or computer—or in the completed work, which is to say a canvas or screening monitor. Your painting-animation process is one of creating, covering, blurring, blending, and transforming surfaces. How would you describe your relationship to surfaces?

CB: Right before meeting Britney in 2017, I was standing in a line of a dozen fans in a cold hallway backstage at Planet Hollywood. The hallway was anything but glamorous, it was the electric room under Britney’s stage, painted with a dirty light yellow-ochre glossy latex paint; there were hundreds of cables lit by malfunctioning fluorescent lights and glazed with rumbling generator sounds. All of us fans were nervous and congealed. At the end of the hall, there was a sheet of white vinyl that would illuminate every time the flash of the camera from the meet and greet went off. Every time, for one millisecond, it would cast the shadow of Britney and the fan who was getting their photo taken with her. Like lightning, the flash would reveal her silhouette on the vinyl screen, and then it would disappear. Every time I was one fan closer to meeting her. I hyper-focused on her silhouette and started thinking about Plato’s cave and enlightenment: the beginning of drawing, the discovery of truth after coming out of darkness, and ‘Your turn Miss, come around, do not touch Miss Spears, do not ask her any questions, just pose and smile for the photo and keep walking to the other side.’

I had never thought about her as a 3D body, I had only seen her on flat surfaces. I am responding to this question with this anecdote because it changed how I thought about flatness. There are organs, blood, consciousness, living cells behind flatness. There is history, movement, and humanity behind flatness.

RS: For me, your work is a reminder that Baudelaire’s drunkenness combines acts of reverie and refusal. How do you—in the spirit of Baudelaire—stay ‘drunk’ on your work?

CB: When I first began these bodies of work, I wanted to poke at us social media consumers, comparing our distant relationship to the subjects on screen to the persona of the flaneur, safe in our homes touristing around the world watching others live their mundane lives, consuming their failures from a distance, commenting here, posting opinions there. The word ‘Epic’ in the genre ‘Epic Fails,’ made me think of this poem, because in [it] Baudelaire invites us to find the epic, the inspiration, and the passion in any place we can: ‘in wine, in poetry, in virtue, as you wish.’ He invites us to be surprised by the everyday scenery, by the bird, the star, the clock, everything that is speaking, singing, rolling, growling … I was making these works right after the pandemic hit, as the refrigerating trucks for dead bodies in the hospital next door were being filled up with corpses.

I can’t escape the fact that I am still a flaneur, comfortable, safe, which grosses me out. But dissecting, slowing down, and reimagining the humans and animals that protagonise these epic fails was a repetitive, soothing activity that kept me sane during the entrapment, and the unknown of the beginning of the pandemic.

*

To see further documentation of ‘Stereotypies’ installed at Cristin Tierney Gallery, please visit: https://www.cristintierney.com/exhibitions/78-claudia-bitran-stereotypies/cover

REFERENCES

Baudelaire, Charles (1997), ‘Be Drunk’, Modern Poets of France: A Bilingual Anthology, translated & edited by Louis Simpson, Story Line Press, p. 73.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey