Spectral Legacies & Haunted Subjectivity: Feminist Temporality in Nina Bunjevac’s Fatherland and Bezimena

by: Marija Antic , March 30, 2023

by: Marija Antic , March 30, 2023

Despite their aesthetic and narrative differences, Fatherland: A Family History (2014) and Bezimena (2019) by Serbian Canadian graphic artist Nina Bunjevac overwhelmingly focus on traumatic experiences and their formative role in the construction of subjectivity and one’s sense of time. Both graphic narratives open with an enigmatic conversation between two women: Nina herself and her mother in Fatherland, and Priestess and Bezimena the Old in Bezimena. The comics begin in the prolonged present moment, within which the linear conception of time collapses, engendering the women’s traumatic return to the past. The female characters are haunted by unresolved traumatic experiences, traces of which appear in the present. It is through their memories that they reconstruct the story-worlds of troubled male protagonists. Such positioning of female characters in the opening chapters—followed by the narrative focalisation of the male perpetrators—largely complicates the process of the reader’s identification and their ethical engagement. What precisely are the implications of showing the reader the perpetrators’ circumstances through the initial prism offered by female characters? This article proposes that the narrative and representational strategies discernible in both Fatherland and Bezimena are politically informed, for they expose larger socio-historical structures of violence and oppression. They imply a critical distance and reflection, while at the same time opening up space for empathy and blurring the distinction between the victim and the perpetrator. Between these concurrent, even opposing orientations towards which Bunjevac’s graphic narratives gesture, we learn how to live more ethically within alternative temporalities and in harmony with the recurring ghosts of our past.

Bunjevac’s comics belong to a growing number of female-authored graphic works rewriting the past through the prism of gender violence and trauma. This movement can be attributed to recent socio-cultural shifts, such as the resurgence of popular feminism, the intensification of ‘testimonial culture’ (Ahmed and Stacey 2001), the global significance of the #MeToo movement and the public’s ever-increasing interest in graphic (auto)biographies. Her work engages with intensely personal and political issues, most notably domestic and gender-based violence, intergenerational history and politics, as well as issues arising from her own complex intercultural belonging. The aim of this article is to examine the interplay between intergenerational trauma, gender violence and the negotiation of cultural identity in Bunjevac’s two graphic novels, Fatherland and Bezimena. Although not strictly autobiographical, both narratives feature Bunjevac’s self-representation, fractured temporality engendered by the traumatic returns of the past, liminality and displacement as means of coming to terms with her own identity. Moreover, both comic books ostensibly centre on the traumatic experiences of the male perpetrators—Bunjevac’s own father in Fatherland and a fictional male character in Bezimena—to draw attention to the pervasive masculinist culture of violence and its impact on women. Drawing on feminist trauma studies and Jacques Derrida’s notion of hauntology (1994), this article proposes that Bunjevac’s reimagined figure of the father whom she never met in Fatherland conjoined with the history of her home country (which no longer exists), as well as her own experience of sexual abuse heavily coded within the registry of myth and symbolism in Bezimena, function as affective workings of Derridean spectres and recurring ghosts. The purpose of these is to excavate silenced or marginalised stories and identities and shine light upon them.

In what follows, I contextualise Bunjevac’s graphic narratives and delineate the key theoretical concepts and frameworks used for my analysis, before turning to close analysis of key textual features of Fatherland and Bezimena. The article will proceed in five parts. The first section provides an overview of Bunjevac’s work while situating it within the context of female-authored diasporic intercultural production. The second part introduces the concept of hauntology in relation to the feminist approach to memory and historiography. The third section explores the relationship between documenting trauma and the artistic form of comics, with an emphasis on how broadening the conceptualisation of trauma affects the (auto)biographical graphic narratives’ relationship with the past. The fourth and fifth sections turn to the representation of multiple temporalities in Bunjevac’s Fatherland and Bezimena, more specifically focusing on how ghostly presences from the traumatic past interfere with the present and the future to conjure a more ethical relationship between the haunted self and the injustices invoked by the ghosts.

Situating Bunjevac’s Work

Bunjevac is a Canadian-born comic book artist who grew up in the former Yugoslavia with her mother and the maternal side of the family, before returning to Canada around the beginning of the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. Her culturally interstitial identity is reflected in both the content and form of her graphic narratives, which prominently feature nested, trauma-informed storytelling and multiple temporal layers. Recollection of personal and collective traumatic memories plays a crucial role in her oeuvre. Her debut collection of comics, Heartless (2012), was well-received by critics, who noted the influence of the American underground ‘comix’ tradition alongside that of the Yugoslav Black Wave cinema, particularly in its focus on social issues and ‘the gritty reality of everyday life mixed with dark humour’ (Lynch 2012: 7). Her subsequent graphic memoir, Fatherland, achieved mainstream international success, appearing on the New York Times best-seller list, and winning the 2015 Douglas Wright Graphic Arts Best Book Award, while her third book, Bezimena, won Best Drawing at the 2019 Angoulême International Comics Festival Award (Sordjan 2021).

Although it is important to acknowledge Bunjevac’s indebtedness to the American alternative ‘comix’ scene and the longstanding production of feminist autobiographical graphic narratives by Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Alison Bechdel and Phoebe Gloeckner, her work should not be considered solely within the Anglo-American context. Moreover, despite her presence in the Balkan underground comics scene and the importance of her Serbian cultural identity to her creative output, Bunjevac herself primarily identifies with ‘the displaced children of Yugoslavia’ (Obradović 2015). For this reason, I argue for the importance of the intercultural locus of her work in ‘a transnationally expanding field of feminist comic art’ (Fägersten et al. 2021: 2), simultaneously within and outside of the North American context that is often considered historically central to the production of feminist comics. Her work can be compared to the Persepolis series (2000-2003) by celebrated French Iranian cartoonist Marjane Satrapi, not only for its cross-cultural mode of testimonial address, but also for its strong affective impact and its efforts to increase readers’ inclination to ‘recognize the humanity of another, and the legitimacy of their suffering’ (Naghibi 2016: 10). However, unlike Satrapi’s minimalist drawings, Bunjevac’s painstakingly detail-oriented visual style creates photo-realistic images that evoke a strong sense of presence, and thus engender empathic connection. By suggesting that Bunjevac produces work that is relevant to both former Yugoslav and Canadian geo-cultural spaces, I follow Mihaela Precup, who argues that Bunjevac ‘occupies an important place in both the Canadian and the Serbian community of alternative comics, not only because of the author’s double national allegiance, but also because she is deeply invested in exploring topics that foreground crucial aspects of both cultural spaces, with a focus on the marginal and the displaced’ (2020: 107). Therefore, both in terms of cultural affiliation and her narrative and aesthetic strategies, Bunjevac’s artistic output expresses her intercultural perspective, shaped not only by her Yugoslav national identity, but also by the North American cultural contexts within which she produces her work. Her comic books thus occupy an ambiguous discursive space characteristic of exilic and diasporic identities. This enables her to explore the issues of cross-cultural mobility, agency, and struggle through displaced and traumatised characters’ personal trajectories.

Fatherland centres on the life and death of Peter Bunjevac (Nina’s father), who, exiled from Yugoslavia because of his ideological opposition to the ruling communist party, settles in Canada. Isolated and unable to integrate into the mainstream Canadian society of the time, he joins the anti-communist terrorist organisation called ‘Freedom for the Serbian Fatherland’ (Srpski Oslobodilački pokret Otadžbina, or SOPO), which aimed to topple the Yugoslav government. He dies in an explosion in 1977, alongside two fellow saboteurs, while making a bomb intended for the Yugoslav consulate in Toronto. Fatherland recounts important, highly traumatic historical events from Peter Bunjevac’s native land that contributed significantly to his exile and demise. It also deals with the effects and legacy of his choices on the Bunjevac family, primarily Nina and her mother.

Like Fatherland, Bezimena (the Serbian word for a ‘nameless’ female) tackles personal and traumatic issues for Bunjevac by creating a narrative distance from painful events. In Bezimena, unlike Fatherland, this is not achieved by recounting historical facts via a third-person omniscient narrator, but rather through the use of intertextual citations, most notably from Greek mythology. By drawing on the myths of Artemis and Actaeon, Siproites, and Callisto, Bunjevac fictionalises and estranges her own experience of sexual abuse. Paradoxically, however, Bezimena focuses on the subject of Benny, a young mentally ill man whose sexual obsession with his former classmate develops to the point where he commits horrific acts of sexual violence against underage girls. Benny’s true actions are revealed only at the very end of the graphic narrative, to his own surprise as well as that of the reader. As a consequence of traumatic experiences, the boundary between fantasy and reality becomes highly porous in Bezimena, creating a hermetically enigmatic text within which the surreal imagery generates the polysemy of meaning and potential interpretations.

Hauntology & Disjointed Temporality

The crux of my analysis of Fatherland and Bezimena is focalising the stories’ fractured spatio-temporal registers, characteristic of both exilic subjectivity and the traumatic experience, in relation to Bunjevac’s graphic representational and narrative strategies and her gendered rewriting of the traumatic past. To that end, I use the concept of ‘feminist temporality,’ which comes from Brydie Kosmina’s (2020) feminist reworking of Derrida’s concept of hauntology.

The notion of hauntology first appears in Derrida’s Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, in which he puts into question Francis Fukuyama’s (1992) ‘end of history,’ —proclaimed after the collapse of communism following the Fall of Berlin Wall in 1989—and traces the spectrality evoked in Marxist thought. Notoriously difficult to define, hauntology is a term, coined by Derrida as an almost-homonym (in his native French) of ontology, that eschews the line of demarcation between presence and absence, between what is and what is not. In other words, the spectre undermines the ontological premise of presence; it is ‘a heterodidactics between life and death’ (Derrida 1994: xviii) and it exists and produces effects despite its physical non-existence. Crucial to hauntology is defying the concept of teleological linearity, as hauntology is most profoundly distinguished by a ‘broken sense of time’ (Fisher 2012: 18). As in the epigraph that opens Spectres of Marx, Hamlet’s phrase ‘The time is out of joint’ offers an opportunity to Derrida to exemplify the logic of haunting and disjointed temporality (within which past, present and future are not separate, easily distinguished categories) in the pursuit of justice and an ethical relationship with time. This is exemplified in Hamlet, as it is the ghost of Hamlet’s dead father who appears to announce the truth and seek justice. As Derrida writes: ‘A spectral moment, a moment that no longer belongs to time, if one understands by this word the linking of modalized presents (past present, actual present: “now,” future present)’ (1994: xix). By collapsing the conventional understanding of time characterised by clear distinctions between then and now, hauntology points to dual directions that operate simultaneously (Fisher 2012, Shaw 2018). As Mark Fisher, a music hauntology scholar, explains:

The first [direction] refers to that which is (in actuality is) no longer, but which is still effective as a virtuality (the traumatic ‘compulsion to repeat,’ a structure that repeats, a fatal pattern). The second refers to that which (in actuality) has not yet happened, but which is already effective in the virtual (an attractor, an anticipation shaping current behavior) (2012: 18).

Both directions are inherently tied to alternative temporalities and a sense of mourning. Importantly, the blurring of distinctions between presence and absence is increasingly facilitated by (tele)technologies: forms of media that connect us to spectres (Derrida 1994: 63)

Nevertheless, as Kosmina points out, the notion of spectrality bears a pressing relevance to the feminist project of gendering history, especially given the uneasy relationship with the past and history for women at large, and specifically for feminist activists and authors who seek to recuperate and/or revise history from the feminist perspective (2020: 902). Within these feminist historiographies, she argues, the metaphor of the spectral presence is inextricably tied with the invisible and/or hidden figures of women (2020: 903). For this reason, she proposes that Derrida’s notion of disjointed time and ‘spectrality represent the beginnings of a non-linear feminist temporality that repurposes narratives of the past for and in the present, while also functioning as a means of lifting the veil and making these ghosts of the past visible’ (2020: 904). I argue that this framework can be used productively to explore and potentially resolve problematic historical legacies and illuminate the relationship with the continuous and pervasive presence of the past for the present and future in Bunjevac’s work. Although prominent in both Fatherland and Bezimena, the mode of authorial self-inscription and hauntological representation take different forms. Both projects are painfully personal and offer a chance for a therapeutic reconsideration of spectral figures and traumatic events in Bunjevac’s life.

Undoubtedly, the representation of such disjointed temporal registers within which the ‘undead’ past and the alternative futures exist simultaneously and produce effects in the present moment—which cannot only be defined as present—is particularly challenging, yet more feasibly expressed through the medium of comics, in which time is rendered spatially. The attributes of each panel—their shape, size and placement—indicate duration, and set the pace or rhythm of actions depicted in comics (Chute 2010: 7). Moreover, as Art Spiegelman, the author of Maus (1991), notes, comics:

are about time being made manifest spatially, in that you’ve got all these different chunks of time—each box being a different moment of time—and you see them all at once. As a result you’re always, in comics, being made aware of different times inhabiting the same space (qtd. in Chute 2006: 201-202).

Nevertheless, Bunjevac’s disruption of time conceived as a linear progression from past to present and future is less manifested in her page design layouts than Spiegelman’s work exemplifies. Rather, it is suggested in her use of splash pages breaking out of frame and her comics’ narrative structure of telling stories within a story. This produces a ‘Babushka’ effect, in such a way that the texts include latent meanings and coexisting multiple temporal layers.

Haunted by the Past: Traumatic Graphic Narratives

Unlike hauntology, trauma studies is a lens frequently used to analyse the formal and textual qualities of comics. In fact, a number of scholars in the field of comics argue that this medium has unique attributes that make it ideal for representing traumatic experiences (Chute 2010, Kunka 2017). Often deemed ‘unrepresentable’ and intrinsically tied to the historical and cultural significance and remembrance of the Holocaust, the exploration of the representability of trauma is at the crux of comics studies which, as Dominic Davis and Candida Rifkind note, is ‘repeatedly drawn to issues of memory and postmemory [that] the field finds itself similarly stuck to the concept of trauma’ (2020: 9, emphasis in original). For Ruth Leys, who traces the etymology of the term, trauma is ‘understood as an experience that immersed the victim in the traumatic scene so profoundly that it precluded the kind of specular distance necessary for cognitive knowledge of what had happened’ (2000: 9). Similarly, Cathy Carruth defines it as ‘an overwhelming experience of sudden and catastrophic events in which the response to the event occurs in the often delayed, uncontrolled appearance of hallucinations and other intrusive phenomena’ (1996: 11). Moreover, Caruth argues that trauma, as ‘the wound of the mind—the breach in the mind’s experience of time, self, and the world—is not, like the wound of the body, a simple and healable event’ (1996: 4). She notes that ‘trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way that its very unassimilated nature—the way it was precisely not known in the first instance—returns to haunt the survivor later on’ (1996: 4). Following Caruth, Dijana Jelača writes:

Trauma is never merely a single event that took place in the past (thus the term ‘post-traumatic’ appears somewhat inadequate, as it implies that trauma is locatable only in the moment of the original event, while everything else is marked as its ‘after’). Rather, trauma is re-ignited and re-experienced, in various forms, through unwitting recurrences in the present, thus blurring the boundary between ‘then’ and ‘now’ (2016: 5).

In this way, the traumatic past that haunts the present and tends to repeat itself bears a striking resemblance to the conceptualisation of hauntology in the narrativization of the past. Importantly, Caruth emphasises the role that narrative plays in dealing with traumatic memory, profoundly marked by a non-linear understanding of time, and invaded by flashbacks and nightmares (1995: 4).

The embedded and circular forms of the trauma-inflected narrative and repetitive nature of traumatic memory lend themselves well to comics’ system of representation. As Andrew Kunka explains, ‘because memory is both fragmented and usually visual in nature, the fragmented, visual nature of the comics medium as a series of individual panels linked by gutters suits the representation of traumatic experience well’ (2017: 84). Moreover, the ‘belatedness’ of the traumatic experience that Caruth foregrounds opens the door for the concept of postmemory, introduced by Marianne Hirsch (1997). Postmemory signifies the intergenerational transmission of trauma which, unlike the immediate experience of a traumatic event, is often transferred through oral history and the family archive (Hirsch 2008: 103). By expanding the narrow understanding of trauma as a single event affecting a single generation, contemporary trauma studies have shifted from associating trauma exclusively with war and other catastrophic events to recognising the quotidian traumatic experiences produced by the hegemonic power structures of oppression and injustice. Relevant to this is the discussion of trauma generated by gender-based violence and sexual abuse, which pays attention not only to a single traumatic event but also to ‘the more sinister and markedly structural indices of a misogynistic social system that produces violence’ (Davis and Rifkind 2020: 9). Similarly, in her exploration of female-authored graphic narratives, Hilary Chute asserts that ‘the traumatic is infused into the everyday culture of women’ (2010: 61). This shift is pertinent to my discussion of traumatic experiences recounted in Bunjevac’s Fatherland and Bezimena, which seemingly focalise the subjectivity of the perpetrator. I understand these narrative strategies not only as challenging the simplified perpetrator-victim binary but, more importantly, they point out the larger socio-cultural and ideological oppressive forces that have produced these subjects, whose destructive actions (and their ramifications) largely belong to the domain of the quotidian, rather than the monumental and extraordinary.

The Ghost of the Father(land)

In Fatherland, Bunjevac pieces together the fragmented genealogy of her family and reconstructs her father’s life by providing a detailed history of her lost homeland. In this way, the several storylines featuring the self, the enigmatic figure of her dead father and the history of the fatherland are intimately connected. Bunjevac recounts her father’s biography in a way that is interlinked with the socio-historical accounts filled with violent and traumatic events that contributed to Peter Bunjevac’s tragic fate. Even though Bunjevac strives to provide historical facts using a controlled tone of objective detachment, the graphic narrative remains permeated with a sense of trauma and mourning born of an intimate experiential reality of the loss of the parent, family, carefree childhood, and finally the homeland, as an effect of these larger socio-political and ideological forces.

Born in 1936 in a Serbian village in Croatia, Peter Bunjevac grew up with an alcoholic, abusive father and a frail mother, in a family in which domestic violence was pervasive and normalised. During World War II, his father was deported to and killed in the infamous Jasenovac concentration camp, and his mother died of tuberculosis soon after the war. His paternal grandparents sent him off to military school after he exhibited disturbing behaviour, most likely symptoms of experiencing traumatic events during the war, as well as the death of both of his parents. He joined the army, but after aligning himself with a dissident faction against the ruling communist party, he was stripped of his military rank and was forced to leave the newly formed Yugoslav state after the war. Ending up in an internment camp in Austria, he met Nikola Kavaja, who significantly influenced his ideological views and later recruited him to the Serbian diasporic terrorist organisation. He received a visa to go to Canada after being hired by a mining company in Thompson, Manitoba. According to Bunjevac, the company actively sought anti-communist migrants from Eastern Europe to keep union protests in check (in Obradović 2015, Bunjevac 2015), which explains why her father was able to receive his visa so promptly. Once in Canada, he was introduced to Nina’s mother, Sally, through pen-pal ads in a Belgrade-based magazine. After an epistolary courtship in which they exchanged ‘carefully staged photographs’ (Bunjevac, 2014), Sally moved to Canada, where the couple got married in 1959 and started a family. They had three children: Petey, Sarah and Nina. However, soon after their marriage, Sally noticed her husband’s illicit activities and started suspecting that he was involved in a dangerous organisation with some other Serbian expatriates. Moreover, when Sally’s mother, Momirka, a former partisan fighter committed to the goals of the communist party, came to visit her daughter and grandchildren, her views clashed with those of Peter and his comrades. Under pressure from Momirka, and after hearing of a bomb in the nearby Croatian community, Sally decided to escape to Yugoslavia with her children, where Peter could not follow them, as he would be imprisoned for desertion. In 1974, Sally departed from Canada under the pretext of visiting her family in Yugoslavia with the two daughters, leaving her husband behind with their only son. Left alone with Petey, Peter attempted suicide. He and Sally exchanged letters in which she gave him an ultimatum to choose between his family and the political cause, yet he responded that he was unable to leave the organisation, as it would have the most disastrous consequences. In 1977, Sally and her family in Yugoslavia received a telegram with news of his violent death in an explosion.

Bunjevac, however, does not narrate her father’s biography in such a linear, chronological order. Instead, the retelling of his life and death is interrupted by the intimate temporality of lived experiences and the grand narrative in the form of a history lesson. Peter’s story is therefore fragmented and contained within Nina and Sally’s memories in ‘Part I: Plan B,’ and within the genealogy of the Bunjevac family and the complex historical account of the fatherland in the second part, ‘Exile.’ The book thus comprises historical and family archive, oral history and personal narrative of both Nina and Sally’s lived experiences, without imposing a strict hierarchy between these modes of storytelling.

The narrative begins in Nina’s Toronto apartment in 2012, as her mother reluctantly recalls her experience of her marriage with Peter and his death. In Sally’s words, he was ‘not an easy man to live with’ (Bunjevac 2014). In addition to being emotionally abusive and obsessed with politics, his clandestine illicit activities brought fear and terror to the family’s daily life. Constantly anticipating danger, Sally protected her children by barricading their bedroom windows with heavy furniture every night. Sally’s behaviour is mirrored in a later panel showing her present-day paranoia, exemplified by her insistence on hearing Nina’s apartment door lock before she leaves. In this way, Bunjevac illustrates the continuity of trauma as the past produces its effects in the present. For Olga Michael, such ‘repetitions with a difference’ and Fatherland’s ‘structural circularity’ serve to give complexity to ‘the relational figure of the otherwise elusive “monstrous” father, [as] it undoes the “blindness” caused by the label of the “perpetrator”’ (2022: 108). However, as the dialogue between Nina and her mother is disrupted, their memory sharing continues to frame the book’s reiterations of the family’s past. It is these complex stylistic and narrative strategies of fractured storylines that give rise to mirrored and/or repeated panels. They serve a larger purpose of foregrounding the Bunjevac family’s traumatic lived past and its continued relevance in the present time.

Sally’s testimony is underscored by her powerless stance, slouched shoulders and broken sentences carried over across panels. The additional purpose of fracturing her testimony and using it to break the narrative continuity is to experience and comprehend the mother and daughter’s affective states of remembrance of traumatic loss and mourning. Moreover, such narrative decisions guide the rhetoric of the book and place the shared female trauma as the central lens through which Bunjevac’s father is seen and introduced. The prioritised perspective shows that Fatherland’s purpose is not primarily didactic. Even though it is invested in representing historical, political, and social matters at large, its main focus is to indicate their overdetermining effects on the family. Furthermore, as Deborah James points out, by emphasising the act of female solidarity in storytelling through recalling personal memories between herself and her mother, Bunjevac ‘challenges the patriarchal authority over memory-telling’ (2015: 530). This is particularly important given the gendered hierarchies of trauma in the Balkans, which privilege male experiences often attributed to patriarchal nationalist and/or ‘heroic’ agendas, within which women as subjects in their own right remain excluded. Within this paradigm, women and their bodies are frequently coded as objects functioning as allegories of a nation under oppressive regimes (Vuković 2018), whose violation further fuels ethnic divisions and nationalist ideologies. In contrast, in Fatherland, the burden of the past that perpetuates gender violence is negotiated by the female subjects themselves.

Bunjevac’s gender revisionist attitude to her family history strongly relates to Kosmina’s non-linear feminist project of resisting the dominant social and ideological structures of power, which render women as hidden, silenced, or invisible, equally prominent in feminist historiographies excavating female histories (2020: 902). However, the sense of female solidarity in the gendered rewriting of history is complicated by the figure of Momirka, who represents the new egalitarian gender politics of the Yugoslav communist regime, proclaimed after the war in acknowledgement of the vital role women played in the partisan resistance (Murtic 2015: 92). Nevertheless, as the nominal political discourse of gender equality was not accompanied by raising feminist consciousness, or by social reforms assuring women’s personal and economic independence, the traditional culture or ‘spirit’ of patriarchy did not die out (Slapšak 1996). Moreover, Momirka’s strong allegiance to the rigid political ideology and her strict, unwavering moral principles do not adhere to the ethics of care for close ones, nor for the placing of value on interpersonal relationships. For this reason, her behaviour also generates violence and emotional abuse within the family. Not only does she call Nina’s father ‘a cold-blooded murderer’ (Bunjevac 2014) and forbids the mention of his name in her household, but her refusal to allow empathy or affection towards him creates a fearful atmosphere that prompts Bunjevac’s older sister, Sarah, to ask her mother for permission to cry after hearing of her father’s death. By emphasising the detail of Sally holding an empty coffee cup in remembrance of her life with her husband and her mother, Bunjevac draws a parallel between Sally’s description of them as she presents them as similarly authoritarian and intolerant of different viewpoints from their own.

Bunjevac’s recounting of events relies on documents in family archives, including her reconstructions of photographs, maps, and newspaper clippings, which are accompanied by oral memories and histories. In Archive Fever (1996), Derrida notes that the etymology of the word ‘archive’ comes from the Greek arche (origin) and archeion, which was ‘initially a house, a domicile, an address, the superior magistrates, the archons, those who commanded’ (1996: 2). This endows material, archival forms of memory with an official power that also has ‘a promise and a responsibility for tomorrow’ (Derrida 1996: 36). Nevertheless, while the recreated historical and family archives establish a sense of authentic representation, the story’s affective and emphatic power derives from the introductory personal testimonies that frame the always elusive, unattainable, and ghostly figure of Peter Bunjevac. His figure remains cold, puzzling, and enigmatic, just as it often appears in his portrait photographs. As Hirsch suggests, ‘[p]hotography’s relation to loss and death is not to mediate the process of individual and collective memory but to bring the past back in the form of a ghostly revenant’ (1997: 20). This is punctuated by Bunjevac’s aesthetics in Fatherland, as her realistic representation of photographs is stylised with her signature graphic pointillism and crosshatching, which produce ‘frames that resemble family photos’ (Levy 2015: 75) and old family photo albums. Moreover, the historic distance that originates from Bunjevac’s narrational presence foregrounds the culturally formative relevance that family photography has as an interface that connects private and public memories, as well as joining the past with the present. However, as Dragana Obradović aptly points out, although Fatherland ‘assumes the genre of a family chronicle … it becomes clear rather quickly how significantly compounded by long-held secrets and suppressed memories the archive actually is’ (2020: 48). Far from idealising family photographs, Bunjevac replicates them as static images that communicate an experience of suffering and pain. The photo-realism and high level of detail produce imagery frozen in time, and thus imbued with a haunting quality. As Caruth notes, ‘to be traumatized is precisely to be possessed by an image or event’ (1995: 4-5). Bunjevac has discussed the investigative labour and affective power of revisiting the sites of memory, which is a necessary part of reproducing family photographs (2015). She talks about discovering that her paternal grandmother—who was physically abused by her husband—had a black eye while scanning and zooming in on her overexposed photographic portrait (2015). The histories of pervasive violence and abuse, both inscribed and effaced from the original photograph, are therefore excavated by technological means. For Derrida, ghosts and technologies are intrinsically connected, as both bring into presence that which is absent. In Bunjevac’s working process, digitally managing and reproducing photographs brought to the surface these ‘absent’ presences—inscribed yet hidden and repressed memories of gender-based violence.

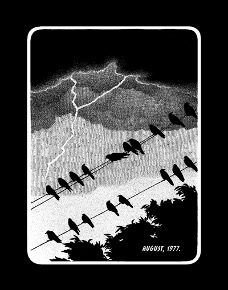

At the same time, the photo-realism of the traumatic events depicted in Fatherland is amplified by the use of symbolism. For instance, the news of Bunjevac’s father’s death is preceded by Momirka’s premonition dream featuring the killing of crows, birds which in Balkan dream interpretations and folk literature signify the news of death (Bunjevac 2014, 2015). The splash pages of the same crows standing on a power line with a thunderbolt in the background and subsequently flying off punctuate the significance of this moment. Furthermore, the overarching preoccupations of Fatherland are foreshadowed by an image of three eggs in a bird’s nest positioned centrally on a black page, which introduces the narrative. These eggs are replicated in a panel showing Bunjevac’s hands drawing them. Arguably, the three eggs represent Bunjevac with her siblings, suggesting an intergenerational bond and the transmission of traumatic memory. The images of birds are similarly used in ‘August, 1977,’ an (auto)biographical short story published in Heartless that dramatises Bunjevac’s father’s death. However, unlike Fatherland, ‘August, 1977’ naively assumes birds’ association with freedom, and their flying away is used as a symbol of Bunjevac’s liberation from the intergenerational trauma, postmemory and legacy of her father’s ideology. By contrast, in Fatherland, the recurrent images of birds function as an ominous motif signalling a ghostly revenant and the mourning of her father. As Derrida suggests, we must ‘learn to live with ghosts [as] this being-with specters would also be, not only but also, a politics of memory, of inheritance, and of generations’ (1994: xviii-xix). In a similar vein, the ending of Fatherland depicts the silhouettes of Aunt Mara, the only person close to Bunjevac’s father, who holds him as a boy while they fall into a dark abyss. This is shown in a panel without a frame, centralising the subjects’ entrapment by darkness that breaks out of time and signals continuity, rather than closure. This endless dark space as a space of buried and repressed memories becomes predominant in Bezimena.

Bezimena–The Unnamed and Untold

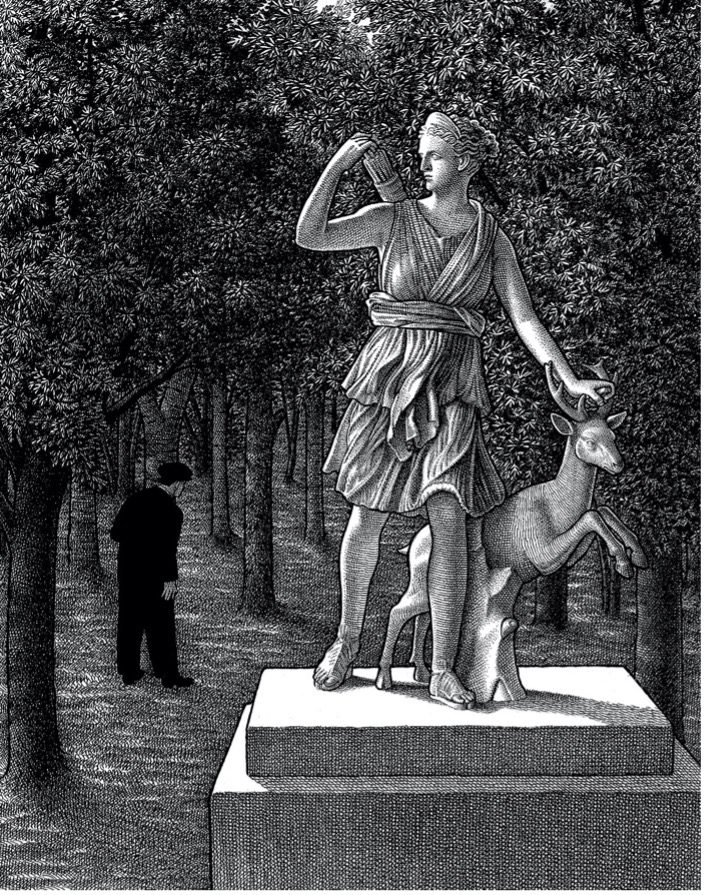

Figure 2: The statue of Artemis (replicated The Diana of Versailles or Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt) on Benny’s walk in the woods and a vignette of an older woman selling an Arktoi (bear-headed) girl as spectres haunting the central narrative of Bezimena.

Highly experimental in form, Bezimena features an embedded, cyclical narrative structure. Its complex textual strategies bury the story’s meaning not only in the primary text; significance can also be discerned from the dark, seemingly empty pages, as well as in Bezimena’s multiple story layers and its extra-textual components (most notably Bunjevac’s ‘Afterword’). However, the spectral presence of these elements—both visible and invisible—is situated in the interstices, gaps, and fissures of the central narrative, through which another story emerges, one more sinister and traumatic than the one presented to the reader.

Bezimena begins in a mythical, atemporal realm in which the titular Goddess punishes the Priestess who disturbs her calm by submerging her under water and initiating her metamorphosis into a strange boy called Benny. Once the Priestess is displaced and reincarnated into Benny, we are immersed into his world as the third-person narrator recounts the story, focalising his perspective. Born into an upper-middle class family in an imaginary European city in the first half of the 20th century, Benny starts showing disturbing sexual behaviour, for which he is brutally punished. Beaten and neglected, he grows up learning to hide his proclivities, yet they manifest in the form of secret predatory voyeurism. Ending up as a janitor at a local zoo, he encounters his old school crush ‘white Becky’ (Bunjevac 2019) —now a grown, beautiful woman—and decides to follow her. By pure accident he finds the sketchbook Becky left behind at the zoo. It is filled with suggestive, erotic drawings, which he believes are an invitation to enact them. The book depicts events that have already happened, such as Benny’s preying on Becky in the zoo and following her home, but it also presents pictures of future sexual encounters scheduled according to lunar phases. The moon and antique pocket watches become recurrent motifs in announcing the sexual fantasies with which Benny becomes obsessed. Following the book’s instructions, he wanders through the woods of the Old Town and recreates sexual events with Becky and her maid, represented in a highly explicit manner, featuring voyeuristic and sadomasochistic scenes. However, after enacting these sexual fantasies, he becomes increasingly tormented and haunted by horrid dreams of his transformation into a stag chased by dogs, and unsettling visions of enigmatic little girls surrounded by teddy bears. After Benny is arrested as the prime suspect in the rape and murder of three underage girls, the sketchbook is revealed not actually to contain these sexual scenes, being filled instead only with children’s drawings. In despair, Benny ends his life by hanging himself in jail. At the moment of his death, Bezimena pulls the Priestess’s head out of the water and asks her: ‘Who were you crying for?’ (Bunjevac 2019).

Depicted through the spirals of transformation, destabilising the initial diegesis as well as its coherent stable identities and temporalities, the book’s central displacement of the subjectivity of the Priestess to be embodied by the troubled boy is reminiscent of Artemis’s infamous punishments, specifically of a young man—Siproites—whom she turned into a woman after he saw her bathing naked. Bezimena’s intertextuality and its use of Hellenistic myths to create spectral characters who inhabit their doubles does not stop here, but is also prominent in Benny’s dream world, in which his partial metamorphosis into a deer takes place. This is a reference to the myth of a celebrated hunter, Actaeon, whom Artemis transforms into a deer for a similar transgression to the one committed by Siproites. Actaeon is then chased and brutally killed by his own hounds. Drawing on these mythical instances of punishment for voyeuristic pleasure—to which Bunjevac alludes in an eerie, mystical way throughout Bezimena—serves to excavate the repressed significative sights of female rebellion, and also suggests the long-standing patriarchal culture of misogyny and sexual exploitation of the female body. The spectre of Artemis follows Benny in his surreal sexual fantasies, which take place in the ancient woods of the Old City, where the Goddess resides. She evidently does so in the form of a marble statue accompanied by a stag, while Benny wanders along the path of the Arktoi stream. Arktoi here refers to little bear-girls (named after the mythical tale featuring Callisto, a she-bear and Artemis’s close companion), which we later see in Benny’s dream sequence. Here it is inferred that Benny’s story shelters within itself his memory of preying on and raping underage girls. In this way, although the mode of narration invites the reader to identify with Benny and follow the story though his point of view, uncanny spectral presences disrupt the dominant story-world and provide cues into the horrible sexual abuse of minors. As Kosmina points out, ‘the spectre functions as a mechanic to draw the past into the present, creating fissures or fractures in the present through which the haunting ghosts of the past can slip’ (2020: 902). These spectral presences hence function as traces or residual layers of the story that belong to a domain prior to that of Benny’s experience, thus alluding to the mystical introduction featuring Bezimena the Old and the Priestess, before her transformation into Benny. Moreover, Benny’s reality full of spectres motivates the reader to reconsider their relationship with the events recounted through Benny’s perspective in the primary text.

Bezimena’s aesthetic style oscillates between realism (recounting Benny’s lived experiences) and dreamlike, symbolic depictions of the moon, owls, and ominous brooch-framed female gazes (the brooch framing of a woman’s eye is also featured on the book’s back cover). However, as soon as Benny finds the sketchbook, Bunjevac almost completely abandons the realistic narrative style in favour of the dreamlike and fairy-tale logic of Benny’s twisted psyche. Importantly, the mysterious sketchbook, as a book within a book, mirrors Bezimena’s drawing design, with a dark space on the left running parallel to a splash page on the right (Manea and Precup 2021: 378). In doing this, Bunjevac highlights the reflexive potential of the medium and Bezimena’s mise-en-abyme. In temporal terms, the sketchbook contains narrative events of the alternative futures situated in the past; it depicts events that have occurred and events that are about to occur, yet, as it is revealed at the end, never existed. Moreover, Bezimena’s timeframes are literally discontinuous and frequently interrupted by Benny’s nightmares and strange visions. The same could be said for the comic’s lack of a clear, stable sense of space. Benny’s city strongly resembles pre-war Belgrade, yet it borrows elements from different cultures, such as the iconography of the Catholic school that Benny attends, with its repressive stance towards transgressive sexuality. Indeed, Bezimena’s spaces often combine mythical elements with real geographic locations and architectural details, suggesting that they exist in ‘the virtual space of spectrality’ (Derrida 1994: 12). This is evidenced in the splash page in which Benny decides to follow Becky as she leaves the zoo. He is shown from behind watching the large stone walls of Belgrade’s Kalemegdan fortress loom over Becky and her chaperone as they walk over the bridge. However, the fortress’s Victor monument is replaced by the statue of the Greek god Hermes, the herald of gods, with winged sandals holding his caduceus entwined by snakes. Highly persuasive and manipulative, he spreads news, but also lies and deception. His figure here clearly signifies the unreliability of Benny’s world, which exists in the interstices between virtual and factual, illusion and reality, producing unease and anxiety that gesture towards the ghostly and seemingly unacknowledged trauma of the female victims, which remains in the dark spaces of Bezimena.

By dealing with the highly sensitive and topical issue of sexual violence against women in an abstract, and rather unemotional and contemplative way, Bunjevac’s representational strategies differ from confessional graphic narratives by Kominsky-Crumb and Gloeckner, whose intimate renditions of sexual abuse are often explicit and largely autobiographical. Dragoș Manea and Precup propose that Bezimena ‘repositions the entire ethical premise of the narrative by suggesting that responsibility for perpetration may lie both within and without the body and consciousness of the perpetrator himself’ (2020: 374). Furthermore, Bezimena’s ostensible lack of focus and care for the victims of sexual violence, and its discounting of the individual culpability of the perpetrator can be interpreted as a self-reflexive critique of the larger socio-political and media discourse on sexual harassment and abuse, which simplifies the systemic power relations of inequality and oppression, engendering gender and sexual violence. In addition, by foregrounding the hypersexualised images of ‘white Becky,’ it comments on how such discourses marginalise non-normative bodies, experiences, and identities. The purpose of Bunjevac’s highly stylised, voyeuristic representations of sexual acts, whose real violence remains heavily coded in myth and symbolism, is to expose the pervasive culture of misogyny and the sensationalisation of sexual violence against women. Felt trauma and suffering are situated in the darkness of the untold experiences of sexual abuse that surround the central story, at times emerging to rupture the illusion of Benny’s fabricated world. This interpretation is supported by the dark ink that signifies the blood or tears of unnamed victims, which flows down the white pages, following disturbing images of penetrating vaginal-shaped windows and keyholes of sexual predators’ scopophilic pleasure. The alternating rhythm of the black pages and flash pages is likewise interrupted by the scenes featuring Arktoi (bear-headed girls) shown in a unit dancing in the woods, as well as by a series of vignettes, one of which shows silhouettes of an older woman selling an Arktoi girl to a waiting man. These images come to haunt Benny and interrupt the diegeses, to which they seem alien and inexplicable. As has been explored by a number of comics scholars, breaking out of the diegeses in this way is regarded as a trauma-informed mode of storytelling that disrupts the domain of the everyday and its temporal logic (Hirsch 1997, Chute 2006). In this way, the perpetual presence and recurrence of trauma are acknowledged by Bezimena’s phantasmatic, uncanny visual register of haunting residual traces of the repressed memory rupturing the narrative.

Bunjevac’s ‘Afterword’ affixes their meaning to the autobiographical as she recounts her own lived traumatic experiences of attempted sexual assault—first as an adolescent in former Yugoslavia, which she explains in detail, then more recently by an older guardian figure who betrayed her trust, about which she chooses to remain silent. In the first one, which takes place in the Serbian town of Aleksinac in 1988, her older high school friend, Snezana, introduced her 15-year-old self to Kristijan by arranging a meeting with him, despite knowing that Kristijan had a history of forcing himself on high school girls and taping their sexual encounters on VHS tapes. The female complicity in sexual violence depicted in Bezimena’s vignette—which Benny witnesses in his hallucinations—thus alludes to Bunjevac’s first experience of sexual abuse. Bunjevac managed to escape Kristijan’s rape attempt, but a similar event occurred once she settled in Canada, and she makes only vague reference to this. As she herself points out in reference to the fatalistic, belated temporality of trauma, ‘the lesson unlearned is bound to return and presents itself with more intensity’ (2019). Bezimena’s textual qualities and narrative structure highlight ‘the temporality of the return’ (Shaw 2018: 6) as the book features spectres that disrupt the conventional linear sense of time. However, it is Bunjevac’s testimony that validates the reading of Bezimena’s spectral use of ancient Greek mythology and fairy-tale symbolism across multiple alternative temporalities to express what remains buried and untold. Surpassing the purely autobiographical, Bunjevac’s commentary stands in solidarity with ‘all the forgotten and nameless victims of sexual violence’ (2019). She ends her confession with a direct address to all those who experienced, and continue to experience, sexual abuse: ‘To find peace, light and drive away the darkness that envelops you.’

Conclusion

Hauntology emphasises the interrelation between past, present, and future, bringing about the crisis of teleological and linear understandings of time. Bunjevac’s narrative and stylistic strategies work to blur not only the boundaries between past and present, but also personal and cultural memory, and victimhood and agency, to challenge the hegemonic masculinist notions of history and to push against the traditional framework of the comics form. In Fatherland, the figure of Bunjevac’s father remains ghostly and unattainable as his image and character is never fully recuperated. Rather, he is framed through shifting female perspectives—those of Sally, Bunjevac herself, and finally aunt Mara, who remains the only person to have had a close bond with him. Similarly, Bezimena’s spectres are elusive, as they rest in the multiple temporal and extratextual layers that at times insert themselves into the central narrative belonging to the fictional perpetrator to announce dreadful sexual violence and introduce its autobiographical and political significance. In both graphic narratives, the haunting memories with which Bunjevac must grapple to conjure an ethical relationship with the self and the past also figure as opportunities to envision more equitable feminist futures that lie at the intersection of gender, body politics, and cultural belonging.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara & Jackie Stacey (2001), ‘Testimonial Cultures: An Introduction’, Cultural Values Vol.5, No. 1, pp.1-6.

Bunjevac, Nina (2012), Heartless: Comics, Greenwich: Conundrum Press.

Bunjevac, Nina (2014), Fatherland, London: Jonathan Cape.

Bunjevac, Nina (2015), ‘Fatherland: A Family History/Nina Bunjevac,’ Stanford CREES, 17 February, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsR1zYRLlBw (last accessed 28 November 2021).

Bunjevac, Nina (2019), Bezimena, Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Caruth, Cathy (ed.) (1995), Trauma: Explorations in Memory, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Caruth, Cathy (1996), Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chute, Hillary L. (2006), ‘“The Shadow of a Past Time”: History and Graphic Representation in Maus,’ Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 199-230.

Chute, Hillary L. (2010), Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, New York: Columbia University Press.

Davies, Dominic & Candida Rifkind (2020) (eds.), Documenting Trauma in Comics: Traumatic Pasts, Embodied Histories, and Graphic Reportage, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Derrida, Jacques (1994), Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, New York and London: Routledge.

Derrida, Jacques (1996), Archive fever: a Freudian impression, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fägersten, Kristy Beers, et al. (eds.) (2021), Comic Art and Feminism in the Baltic Sea Region: Transnational Perspectives, New York: Routledge.

Fisher, Mark (2012), ‘What Is Hauntology?’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 16-24.

Fukuyama, Francis (1992), The End of History and the Last Man, London: H. Hamilton.

Hirsch, Marianne (1997), Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hirsch, Marianne (2008), ‘The Generation of Postmemory’, Poetics today, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 103-128.

James, Deborah (2015), ‘Drawn Out of the Gutters: Nina Bunjevac’s Fatherland, a Collaborative Memory’, Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 527-532.

Jelača, Dijana (2016), Dislocated Screen Memory: Narrating Trauma in Post-Yugoslav Cinema, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kosmina, Brydie (2020), ‘Feminist Temporalities: Memory, Ghosts, and the Collapse of Time,’ Continuum, Vol. 34, No. 6, pp. 901-913.

Kunka, Andrew (2017), Autobiographical Comics, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Levy, Michele (2015), ‘Nina Bunjevac. Fatherland,’ World Literature in Review, Vol. 89, No. 5, pp. 74-75.

Leys, Ruth (2000), Trauma: A Genealogy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lynch, Jay (2012), ‘Introduction’ in Bunjevac, Nina (2012), Heartless, Greenwich, Nova Scotia: Conundrum Press.

Manea, Dragoș & Mihaela Precup (2020), ‘‘Who were you crying for?’: Empathy, Fantasy and the Framing of the Perpetrator in Nina Bunjevac’s Bezimena,’ Studies in Comics, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 373-386.

Michael, Olga (2022), ‘Looking at the Perpetrator in Nina Bunjevac’s Fatherland,’ Journal of Perpetrator Research, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 80-110.

Murtic, Dino (2015), Post-Yugoslav cinema: Towards a Cosmopolitan Imagining. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Naghibi, Nima (2016), Women Write Iran: Nostalgia and Human Rights from the Diaspora, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Obradović, Dragana (2015), ‘I Only Belong to One Tribe: The Displaced Children

of Yugoslavia,’ Balkanist, 14 May, http://balkanist.net/profile-nina-bunjevac-author-of-fatherland/ (last accessed 27 July 2022).

Obradović, Dragana (2020), ‘Filial Estrangement and Figurative Mourning in the Work of Nina Bunjevac’ in Comics of the New Europe: Reflections and Intersections, edited by Kuhlman, Martha and José Alaniz, Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 47-66.

Precup, Mihaela (2020), The Graphic Lives of Fathers: Memory, Representation, and Fatherhood in North American Autobiographical Comics, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Shaw, Katy (2018), Hauntology: The Presence of the Past in Twenty-First Century English Literature, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Slapšak, Svetlana (1996), ‘OGLEDI V-VIII: Žene i rat u bivšoj Jugoslaviji,’ Republika, No.145, pp. 5-8.

Sordjan, Anna Maria (2021), ‘Nameless: Exploring Bezimena by Nina Bunjevac,’ Femme Art Review https://femmeartreview.com/2021/04/12/nameless-bezimena-by-nina-bunjevac/ (last accessed 20 July 2022).

Vuković, Vesi (2018), ‘Violated Sex: Rape, Nation and Representation of Female Characters in Yugoslav New Film and Black Wave Cinema,’ Studies in Eastern European Cinema, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 132-147.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey