Solving the Crimes of Patriarchy: Meta-Lucidity and Middle-Aged Women in Happy Valley & Broadchurch

by: Terri Carney , June 14, 2021

by: Terri Carney , June 14, 2021

Introduction

In 2021, there is a growing global awareness of sexual violence, and a mounting public critique of patriarchal society. The international popularity of the female detective in contemporary TV shows offers new formulas for how we solve the crimes of the patriarchy, which are on display in the two TV series analysed in this paper: Broadchurch (2013-2017) and Happy Valley (2014-2016). Both series centre midlife women as victims, criminals, and justice-seekers who face child molesters, murderers, and rapists in contemporary gothic settings. Indeed, the magnificent locales—the shadowy hills of West Yorkshire in Happy Valley and the dramatic cliffs of West Bay in Broadchurch—soon reveal a sinister presence, as if a dark cloud or a murder of crows moved overhead. The women protagonists are fitting insurgents in a male-dominated society that devalues middle-aged women, and they skilfully navigate the systemic misogyny of the legal system and the quotidian miasma of sexism in their personal and professional lives. Both series offer new models for justice that go beyond the simplistic notion of individual culpability to recognise a culture of toxic masculinity as the real criminal.

Once the crimes are solved, the women face the problem of how to raise sons of toxic masculinity, and we ask the larger question: how do we metabolise the sexism and racism endemic to patriarchy? Indeed, these television narratives are gothic allegories for how we might think beyond the patriarchy, developing what Linda Martín Alcoff, in her book Rape and Resistance, refers to as ‘meta-lucid subjects . . . who are aware of the effects of oppression in our cognitive structures and of the limitations in the epistemic practices grounded in relations of oppression.’ (2018: 32) The middle-aged, gothic heroines of Happy Valley and Broadchurch solve complex problems by staying rooted in community and retaining clear-sightedness in the murkiness of patriarchal oppression. Both visual texts stage an interrogation of the formulaic truths of the detective genre and the deceptive comforts of the domestic sphere by positioning women as detectives and justice-seekers, and creating new configurations of women-centred families who must now raise the sons of toxic masculinity and rape culture.

In her book Gothic Television, Helen Wheatley argues that the medium of television is well-suited to gothic narratives, as both are centred in the domestic space. The gothic genre is historically a site of patriarchal critique and a genre produced and consumed by middle-class women. Featuring women as heroines and the secrets and anxieties of family life, the two series in this study follow a long tradition of bringing gothic horrors into the living rooms and everyday lives of British women. As Wheatley contends, the serial and intimate nature of television inscribes an awareness of the viewers as invested in the reflection and analysis of their own experience as women scripted by the patriarchy.

Women Having a Bad Day

In the opening scene of Happy Valley, we can see that Sergeant Catherine Cawood (Sara Lancashire) is having a bad day. She and a fellow female officer respond to a call regarding an intoxicated man threatening to light himself on fire at a local playground. As Catherine talks to the young man, she learns that his girlfriend has just left him for his best friend. She is left to resolve the tense situation while the male expert called in by police is stuck in traffic and never arrives, highlighting a major theme of the show, and the vehicle for much of the dark humour: men in high positions are removed from the messy work done by women at the street level, and when women do not do what men want, there is a threat of violence. Catherine’s sharp wit and irony make her a great cop, and she shows up to the scene with sunglasses and a fire extinguisher that she buys at the corner store, announcing to her colleague who comments on the glasses: ‘Well, he can send himself to paradise—that’s his choice—but he’s not taking my eyebrows with him.’ (S1E1).

It is difficult to overemphasise the horrors of Catherine’s everyday life. Her daughter Rebecca (Elly Colvin) was brutally raped at seventeen, and as a result gave birth to a baby she did not want. When Rebecca killed herself at eighteen, Catherine was left to raise her grandson Ryan (Rhys Connah). Both her husband and son moved out, unable to accept him as their family. Happy Valley is a town devastated by drugs, and Catherine’s policework is mostly cleaning up the mess of that reality, but the drugs keep coming. Her now ex-husband, Richard (Derek Riddell), remarried a younger woman and still turns to Catherine for support and the occasional shag. Catherine’s sister, Clare (Siobhan Finneran), is a recovering heroin addict and alcoholic. In the first episode of season one of the series, Catherine learns that her daughter’s rapist, Tommy Lee Royce (James Norton), has just been released from prison.

While Ellie Miller’s (Olivia Colman) life is not marred by the same tragedies of Catherine’s life, she is a female detective in a man’s world. When we meet DCI Miller in the first episode of Broadchurch, she has just returned from vacation and cheerfully distributes gifts to her work colleagues before reporting to her superior’s office to assume the leadership position she was promised. As she saunters in to collect her promotion, she is all smiles, but her smile quickly fades as she is told the position was given to a man from another town, a DCI who failed to get justice in his last murder investigation. She snaps back to her senior officer, a woman: ‘A man? What happened to I’ve got your backing?’ Ellie is never given a satisfactory explanation as to why she is being replaced, and when she finds out that DCI Alec Hardy (David Tennant) failed to close his last investigation, she is incredulous.

Like Catherine, Ellie is a mother, and they both face struggles familiar to women balancing professional and personal commitments. Children and the spaces they occupy appear in both series from the opening scenes, and raise questions about motherhood and the generational legacy of toxic masculinity. Happy Valley’s playgrounds are overrun with drugs and their damaging effects, and in the first scene Catherine handles the man with the lighter on top of the swing-set while children and moms watch from the sidelines. Broadchurch season one opens with a shot of eleven-year-old Danny Latimer (Oskar McNamara) standing on the cliffs over the ocean in the dark, and then cuts to a camera moving through his house as his parents and sister sleep, focusing on his bedroom door and then his empty bed. These moments are a ghostly foreshadowing of what his family and community will soon learn: that Danny has been murdered. His mother Beth’s (Jodie Whittaker) growing suspicions that something is terribly wrong contrast with the cheerful innocence of a field day for elementary school children who are laughing and running around her as she searches for Danny, who, unbeknownst to her, is already dead.

While both series open with the common trope of the bad day, we soon begin to wonder if every day is a bad day for women in the toxic universe of violent patriarchy. The striking locales and the everyday routines of the women protagonists are haunted by gothic themes of dark secrets, vulnerable women, and evil male villains. However, while we can easily identify individual villains in both shows, it is the amorphous yet omnipresent patriarchy, or toxic masculinity, that functions as the real villain in these updated gothic tales. The insidiousness of such a condition is not easily contained or resolved in the traditional detective genre, with its reliance on rational proof and individual culpability, so each series incorporates gothic elements to convey the eerie durability and pervasive systematicity of patriarchal culture. As Wheatley notes in Gothic Television, the gothic serial incorporates artistic techniques to capture the intense subjective and non-rational experiences of the gothic heroines, as a way to give representation to that which is silenced or lost in a culture that deauthorises women and assigns them a ‘credibility deficit.’ (Martín Alcoff 2018: 48)

Gothic Elements

Happy Valley and Broadchurch bring the incredible resilience and relentlessness of the patriarchy to the small screen, and capture the horror of women’s experience in subjective flashbacks of violence, ghostly visions, and a rootedness in moody and dramatic landscapes. These shows also position middle-aged women more as agents than victims, as they fight back and go to battle in public against the villains of toxic masculinity, armed with their professional status as cops. Gothic heroines as agents rather than victims have a long history, despite stereotypical notions of the genre. (Ledoux 2017: 2)

The gothic genre has long been used to highlight the oppression of women, and to express anxiety over a nameless or formless fear. Both shows in this study share key gothic elements, including settings of natural beauty with a sinister air, female victim-heroines, and male villains. The fictional town of Happy Valley is located on the English moors of West Yorkshire, a classic locale reminiscent of the quintessentially gothic novel Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë. Metafictional references to the novel inscribe an intertextual intentionality that encourages the viewer to connect the two by providing a model of female consumers of gothic texts.[1] In season one, episode one, Catherine tells her sister Clare that Tommy Lee Royce should rot in a shallow grave on the moors, and then the scene cuts to Ann Gallagher (Charlie Murphy) singing in her car to Kate Bush’s song ‘Wuthering Heights,’ moments before she is kidnapped and then raped by Royce. Catherine and her daughter Rebecca share names with classic gothic heroines. In addition to these intertextual winks, Happy Valley creates a gothic atmosphere through Catherine’s frequent visits to the cemetery to spend hours looking at her daughter’s grave, and her disturbing visions of her dead daughter in the back seat of the car, or in the office at work.

A pillar of the gothic genre is the battle between good and evil that is never finished, lending the genre a characteristic moral ambiguity. In Happy Valley, Catherine and Tommy are locked in an intense battle as representatives of good and evil, yet at key moments the series positions them as interchangeable. In the first episode, both Catherine and Tommy say ‘stop wriggling’ as they shove someone into the back of a van. Clearly, the contexts are very different: one is a rapist and criminal kidnapping a young woman, while the other is a cop arresting a young man who is a drug dealer, but the words they utter, and the action of shoving someone into a van, connect the two characters. Later, in season one, episode six, through a scene cut between Catherine’s kitchen and Tommy’s canal boat, we notice the same milk carton on both counters, unifying the two spaces and characters. Repeated phrases and actions, along with shared habits, allow for slippage and bleeding among characters and situations, which further undermines the traditional crime genre idea of good person/bad person. The larger system itself is pervasive and insidious, and we are all actors in the same play, with a limited number of available roles. Such staging points to the impossible criminal who cannot be captured.

If Catherine is the haunted and traumatised heroine of Happy Valley, who obsessively hunts and takes down the villain Tommy Lee Royce, predator of young virginal women, in Broadchurch it is Ellie who is the victim/heroine of the gothic tale. With her boss and partner DCI Alec Hardy, Ellie takes on her first murder investigation, that of Danny Latimer, the son of her neighbours and close friends Beth and Mark Latimer (Andrew Buchan). The methods and procedures of the investigation rely heavily on forensics and empirical data collected through interviews and cameras, but they do not lead the detectives to the killer, who is only discovered when he decides he wants to be caught. The killer turns out to be Ellie’s husband Joe Miller (Matthew Gravelle), and this staggering revelation retroactively reduces her to the status of gothic heroine who has been living in the house with the evil villain all along. In the season one finale, when Ellie returns home to collect belongings for her and her two sons, who will now stay in a hotel while Joe is in custody and the investigation wraps up, she steps on a slug in her living room. The slug and the slimy streak left on the rug symbolise the evil that was in her home the whole time without her knowing. As she leaves the house, she turns for one last look and says ‘We were happy here,’ bringing to life Sara Ahmed’s description of a feminist consciousness as aware of the ‘violence and power concealed under the language of civility, happiness, and love, rather than simply or only consciousness of gender as a site of restriction of possibility.’ (2017: 62)

Like Happy Valley, Broadchurch includes many graveyard scenes, and features a central gothic-style church on the hillside overlooking the town. The vicar of the church is a recovering alcoholic who is often out strolling in the late hours of the night, and Beth Latimer sees a vision of her dead son at the conclusion of a nighttime vigil in his memory. Mark Latimer has recurring dreams of hearing Danny crying, and opening his bedroom door to find him huddled on the floor, soaking wet, where Mark sits next to him and hugs him, also crying. While it is clear that Mark is dreaming, viewers note the eerie similarity to the opening scenes of the series, where the ghost of Danny seems to be floating through the Latimer house, represented by the eye of the camera. Graveyards, churches, mysterious characters, and ghost sightings all contribute to the reading of Broadchurch as a gothic allegory.

Patriarchal Toxic Masculinity is the Real Criminal

In both series, we can identify a male villain: Tommy Lee Royce is the rapist and murderer whom Catherine hunts in Happy Valley, and Joe Miller is the child killer and potential molester in Broadchurch. It is notable that in each story the justice system falls short in terms of finding the truth and meting out appropriate punishments. Tommy Lee Royce never serves time for Rebecca’s rape, and Joe Miller is acquitted of all charges despite his apparent culpability. It soon becomes clear that the justice system is an ineffective way of handling the insidious and cyclical crimes of a toxic patriarchal culture, and each series communicates the pervasive and continual nature of these crimes.

Happy Valley is a nickname for the Calder Valley, where the series is set. The ironic moniker for the fictional town indicates the prevalence of drugs and addiction in the region. Indeed, the effects of widespread drug use, and the mess this creates for Catherine and the justice system, leave her feeling helpless to fight the problem, which permeates all levels of society and cannot be solved at the local level. She complains about it all to her sister Clare, saying that she ‘only gets to mop up the mess at the bottom’ and ‘I just tidy the streets, me’. She also tells her ex-husband Richard, who is a journalist, and enlists him to write a news story about the larger drug problem, which she understands at a global level of international suppliers and chains of money and power that exploit and poison the people of her town. Without that larger view, she contends, there is no way to stop the drugs from coming.

It is the drug trafficking and capitalist greed that create the conditions for the kidnapping, death, and rape of women in Happy Valley, fuelled by male ambition and desire. After stumbling on the local drug traffickers’ operation and getting swept up in a thick web of greed and corruption, a mediocre accountant named Kevin (Steve Pemberton)—referred to as ‘Kev’—orchestrates the kidnapping of his boss’s daughter as a way to get money to send his own daughters to an expensive private school. His boss’s name is Nev (George Costigan), and the two men work in the business their fathers fought over, framing the current struggle between Kev and Nev as long-standing and multi-generational, adding further irony to their interchangeable names. As a result of Kev’s kidnapping scheme with the drug dealers, Nev’s daughter ends up in the hands of Tommy Lee Royce. While moving the kidnapped Anna to another location, Tommy kills Catherine’s colleague and friend Kirsten (Sophie Rundle), a young policewoman who pulls over the kidnapper’s van for a broken taillight. While it is only Tommy who kills Kirsten and rapes and mistreats Anna, we see the connection of these crimes to the larger chains of men with drugs and money who trade and exploit the women in their lives as just another commodity.

It is not just Kev and Nev, or Tommy and the drug dealers, who are part of the chain of violence and destruction that leaves women as victims in their wake. Before she is killed by Tommy, Kirsten has an encounter with a drunk councilman who just had a minor car accident, and he makes a big scene threatening her and calling her a ‘cunt’ when she tries to give him a breathalyser test. Catherine arrives on the scene and has Kirsten’s back: when Catherine finds a small bag of cocaine in his car, she arrests him and presses charges despite his protests, bribes and threats. Later, on the day of Kirsten’s funeral, Catherine’s male superior asks her to drop the case against the councilman, citing the politician’s support for police and other political favours delivered through the old boys’ network. Catherine seems exhausted and perhaps exasperated in this scene, which highlights the insignificance of women’s efforts to be good cops and rid the streets of drugs, while male cops in higher positions enable the cycle to continue and even flourish. Catherine refers to the privileged councilman as a ‘Teflon twat,’ an apt phrase that captures the incredible difficulty in naming or holding accountable the beneficiaries of the patriarchy.

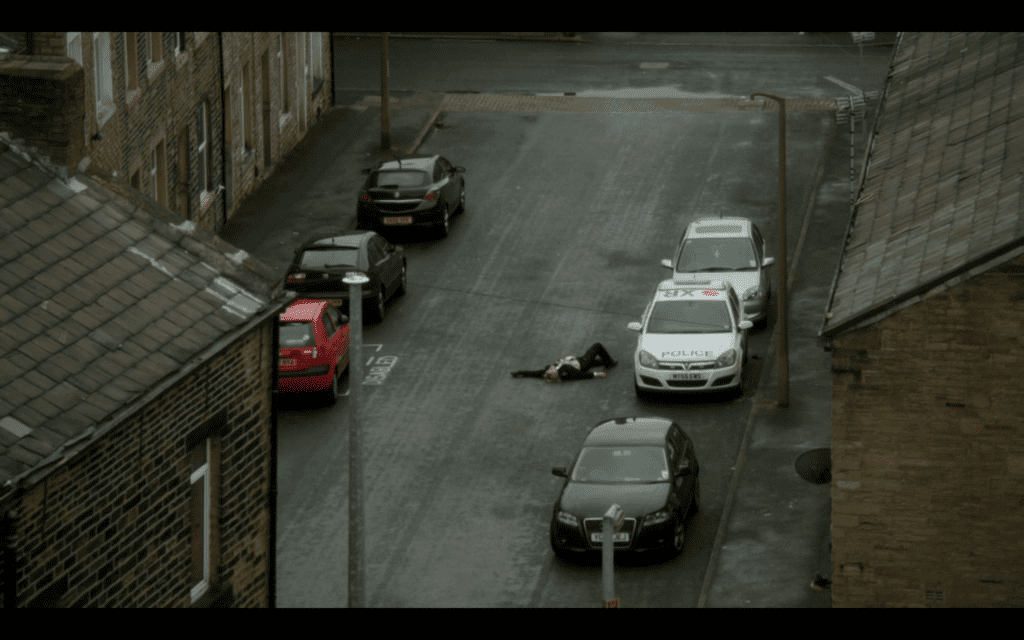

Symbolic of women’s herculean efforts to be good cops and to ‘clean the streets,’ both Kirsten and Catherine suffer terrible and brutal physical attacks by Tommy Lee Royce, one resulting in Kirsten’s death and the other in Catherine’s hospitalisation. Significantly, both women are shown from above laying in the street bleeding or dead, in uniform and immobile. Two professional women fighting the evil villains of toxic patriarchy and rape culture, beaten and left in the street.

In Broadchurch, Joe Miller meets with eleven-year-old Danny Latimer in secret for months so they can be close and hug. When he confesses to Danny’s murder, he tells DCI Hardy that he was ‘in love’ with Danny and that he couldn’t explain it even to himself: ‘all i ever asked was for him to hold me.'(S1E8) Throughout the series we see several instances of characters wanting hugs or secret meetings with children, suggesting a parallel with Joe that invites viewers to compare and judge the different cases. On the least alarming end of the spectrum, we have Beth, who after Danny’s death asks Tommy (Adam Wilson), Ellie’s son and Danny’s best friend, for a hug in the hallway of her house, explaining that she misses Danny’s hugs. Jack Marshall (David Bradley), an older man who runs the convenience store and heads up the boys’ club, also likes to hug young boys, and while at least one young man finds his hugs uncomfortable, Jack’s explanation of missing his young son who died years ago in an accident seems plausible, and goes some way towards assuaging viewers’ suspicions of him as a potential child molester. In season two, we discover that Mark has been meeting Joe and Ellie’s son Tom in a trailer to play video games, and that it is a secret between the two. At one point we see them hug.

This strange leitmotif of requests for hugs from children calls attention to the larger cultural ideas about toxic masculinity and the prohibition of male emotion or desire for affection. In a similar fashion, different women find themselves in the patriarchal position of being blamed for the crimes of men. Ellie criticises suspect Susan Wright (Pauline Quirke) for not knowing her husband was sexually abusing her daughters until he kills one of them. Yet, later in the series Beth questions Ellie in the same way after Joe confesses to the murder: how did she not know it was him? The repeated tropes of the woman blamed for her husband’s criminal actions and the mother who fails to protect her own children speak to the way patriarchy assigns blame and holds women accountable for the actions of others, even while men refuse to take responsibility for their own criminal behaviour.

Catherine blames herself for the deaths of both Rebecca and Kirsten. Ellie blames herself for not seeing that Joe was the killer. Yet men in both shows who are guilty of crimes refuse to take responsibility for actions they clearly took. When Kev is in jail for his role in the kidnapping of Anna, he says ‘it’s not my fault.’ When Mark Latimer visits Joe’s prison cell before the court date, Joe shifts the blame for Danny’s death (‘an accident’ he says) to Mark for being a bad father. Later, in court, when Joe Miller shocks the town with his not guilty plea, he explains to his lawyer that he ‘can’t go to prison for Danny’s death.’

Season three of Broadchurch highlights the disturbing continuum of everyday sexism to sexual assault when rape victim Trish’s (Julie Hesmondhalgh) otherwise supportive and gentle ex-husband and current male partner engage in controlling behaviours that involve stealing her laptop and breaking into her house to install spy cameras, both intending to monitor and control her movements. The sliding scale of misogyny and violence in both series points to an inescapable morass that our heroines must navigate.

Women in Solidarity & the Sons of Patriarchy

While the patriarchy as depicted in these shows is undoubtedly suffocating, the women in Happy Valley and Broadchurch do manage to survive and resist in two major ways that women everywhere use to endure everyday life: friendship with other women, and an ironic consciousness of their position in the patriarchy. Both provide recourse to women, offering support and valuable input with which to understand their own positions in a world that devalues their authority and gaslights them at every turn. Women working together can right themselves in what Martín Alcoff calls the ‘epistemic injustice’ of patriarchal society (2019), and Anna Williams calls ’emotional invalidation,’ a concept from cognitive psychology that she connects with the gothic genre. (2020)[2]

Fittingly, Happy Valley and Broadchurch end a season with an image of feminist solidarity, and a momentary brightness that serves as a pause in the violence and a space for renewal. Broadchurch brings Ellie and Beth together in a scene of renewed friendship surrounded by their children (S2E8); Happy Valley ends with Catherine having put Tommy in prison, now smiling with rare sunshine on her face as she and Clare watch Ryan playing (S1E8). However, these peaceful scenes of centred friendship and collective motherhood are marked by the presence of the sons of toxic patriarchy who serve as gothic Frankensteins: creations of victim and demon who portend an ambivalent and potentially violent future. In her study of ambivalent motherhood in crime television, Amanda Greer refers to children of rape as ‘monstrous’ and examines the ways that ambivalent motherhood can destabilise the patriarchy. (2017: 342) Catherine’s grandson is the son of Tommy Lee Royce. Ellie’s boys are Joe Miller’s sons. Throughout each series the sons of toxic masculinity are presented to viewers as potentially following in their fathers’ footsteps: Ryan’s violent outbursts and constant bad behaviour at school cause even Catherine to doubt his goodness; Tom’s mysterious behaviour in the wake of Danny’s death, his defence of his father during the trial, and the porn she finds on his phone leave Ellie to wonder how he will be influenced by his genes.

Conclusion

Kristyn Gorton’s study of the heroic women of Sally Wainwright’s Happy Valley expands the social realist tradition of British television to give it a woman’s perspective and voice. Women are angry about social injustice. They are tired of life in the patriarchy. Wainwright’s character Catherine Cawood embodies this cultural moment, and provides viewers with a new kind of superhero, one who is not able to completely vanquish the enemy but will keep fighting another day. And who better to bring us this formidable middle-aged warrior than a middle-aged television writer, long over-looked by the patriarchy and from a middle-class background? Sally Wainwright’s northern roots are reflected in Catherine’s rootedness in her small community, a quality connected to her relational morality and complex understanding of justice. (Salter Dromm 2021) And while Broadchurch‘s Ellie may not measure up to Catherine’s level of badass warrior, she certainly fits the pattern of a strong, Northern woman who is caught in the tangle of patriarchy and toxic masculinity, and yet stays in her community to live in the complex aftermath of the family secrets that almost destroyed her and her town.

These contemporary gothic narratives attempt to catch the monster of patriarchal violence in all its pervasiveness and Teflon evasiveness. Whether it is gaslighting, epistemic injustice, or the crooked room of the master’s house, by employing gothic elements in the detective story these visual narratives expand beyond the limits of rational approaches to truth and justice, and signal a pernicious sexism at the heart of western epistemology, one that marginalises the experiences of women. Indeed, feminist critiques of rationality and of philosophical knowledge recenter the experiential and embodied nature of the knower. (Tuana 1992: 116-17)

After reading Southard’s study on the rise of Revolutionary Gothic, I am now convinced that the TV series I analyse in this paper belong to this new vein of gothic: ‘[t]hese stories don’t try to comfort you with victory; they unsettle us with the implications of ongoing defeat.’ (2019) Although Southard’s study focuses on the horror of racism in Jordan Peele’s Get Out and the evils of capitalism in Parasite, the monster of patriarchy in Happy Valley and Broadchurch stands as a matching third pillar of gothic horror in this category.

Notes

[1] Helen Wheatley in her book Gothic Television explores how gothic television inscribes a model of viewership. (pp. 18-21)

[2] Melissa Harris-Perry describes a similar disorientating phenomenon that black women experience as ‘the crooked room’. (2011)

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living the Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University Press.

Gorton, Krysten (2016), ‘Feeling Northern: ‘Heroic Women’ in Sally Wainwright’s Happy Valley (BBC One, 2014),’ Journal for Cultural Research, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 73-85.

Greer, Amanda (2017), ‘‘I’m not your mother!’: Maternal Ambivalence and the Female Investigator in Contemporary Crime Television,’ New Review of Film and Television Studies, Vol.15, No. 3, pp. 327-347.

Harris-Perry, Melissa V. (2011), Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ledoux, Ellen (2017), ‘Was There Ever a ‘Female Gothic’? Palgrave Communications, No. 3, Art. 17042, doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.42, (last accessed 8 January 2020).

Martín Alcoff, Linda (2018), Rape and Resistance, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Salter Dromm, Heather (2021), ‘Breaking Down Sexist Barriers in Happy Valley,’ MAI Issue 3, 20 April, https://maifeminism.com/breaking-down-sexist-barriers-in-happy-valley/ (last accessed 2 May 2021).

Southard, Connor Wroe (2019), ‘Parasite and the rise of Revolutionary Gothic,’ The Outline: Culture, 20 November 2019, https://theoutline.com/post/8279/parasite-us-revolutionary-gothic?zd=1&zi=7fgnz2nc (last accessed 8 January 2020).

Tuana, Nancy (1992), Women and the History of Philosophy, New York: Paragon House.

Wheatley, Helen (2006). Gothic Television. Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press.

Williams, Anna (2020), ‘Grad School Gothic: The Mysteries of Udolpho and the Academic #MeToo Movement,’ Gothic Studies, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 115-130.

TV Series

Broadchurch (2013-2017), created by Chris Chibnall (3 seasons).

Happy Valley (2014-2016), created by Sally Wainwright (2 seasons).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey