Socialist Superwomanhood & Policing the Nation in the Hungarian TV Series Linda

by: Julia Havas , June 14, 2021

by: Julia Havas , June 14, 2021

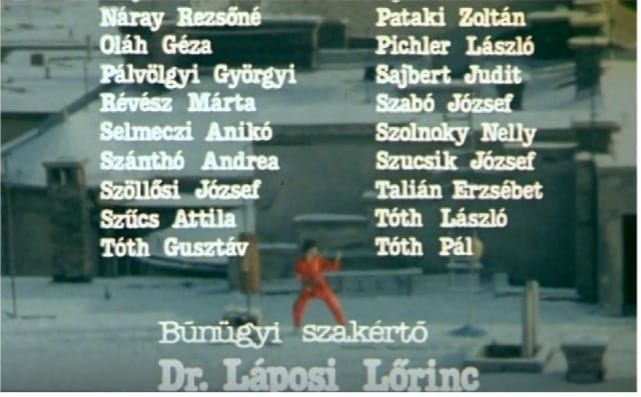

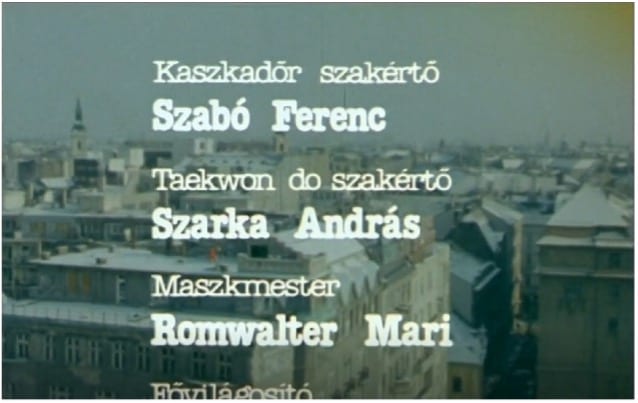

Eastern European popular culture witnessed several curious media phenomena in the 1980s, reflecting the region’s cultural and political transitions. Among these, the Hungarian crime procedural Linda (1984-1991) ranks especially high for its endurance in cultural memory and investment in transcultural and national genre hybridity and intertextuality. But perhaps the most resonant feature of the series is its upsetting of the gender politics of the era’s ‘tough’ crime and action genres in ways that were uncommon for contemporaneous TV cultures on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Encompassing three non-consecutive series broadcast in 1984, 1986 and 1989-1991, and becoming a shorthand media signifier of the decade, Linda follows the titular character, played by freshly-graduated and baby-faced actor Nóra Görbe, as she joins the Hungarian police force right after herself graduating from high school. Linda positions her as an outlier from the get-go: not only is she an unusually young-looking, androgynously skinny, small and fit woman sporting a dark, boyish mullet, seemingly no make-up, and often bizarre outfits—features that in themselves read as markers of difference for late-socialist Hungary’s reigning notions of desirable and recognisable femininity—but is also a green belt practitioner of Taek-won-do, which she deploys to fight the criminal underworld (Görbe learned Taekwon-Do for the role, and had achieved a green belt by the start of the second series). Her fighting skills are inspired by the era’s much-hyped East Asian martial arts films, notably those of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, movies which, according to series creator-producer-director György Gát, were the impetus for Linda’s premise. (Kiricsi 2007) The martial arts element was meant to spice up the crime procedural genre, but while this was already familiar to Hungarian viewers through imported programming (Imre 2016: 200), it was a rarity in domestic television production. Gát’s recounting of Linda’s genesis emphasises how 1970s US television inspired the transplanting of episodic[1] crime programming’s typical visual, narrative, and character motifs into the Hungarian milieu. The Hungarianised blending of martial arts/police procedural genres involved adding two further novelty features: a heightened use of (sarcastic, self-referential, and Hungarian comedy tradition-derived) humour, and a female hero whose incongruous position creates a tension endlessly exploitable for episodic television. (Kiricsi 2007) This gendered novelty is however couched in all-too familiar production history discourses around casting the series’ female star: Gát, who was married to Görbe throughout the series’ run, describes Linda’s development as a casting-couch romance, that is, as his way of seducing then-drama student Görbe by lying that he had a star-making role for her, which then forced him to come up with the pitch. (Kiricsi 2007)

This artist-muse romance’s significance for the series’ position in Hungarian cultural consciousness—beside harnessing the fictional character’s unsettling features into a safely masculinist production historiography—is Görbe’s resultant controversial celebrity and discourses around her acting ability, often framed as being somewhat lacking in relation to the supporting cast of veteran actors surrounding her. Although such celebrity narratives are recognisable from the culture industries’ gendered production histories, Görbe’s parentage exacerbates the discursive dubiousness of her acting skills, and resonates with the series’ portrayal of both fatherhood and the Hungarian media industries: Görbe’s father was János Görbe, legendary stage and film actor and staple of exportable, political art cinema between the 1940s and 1960s. The art cinema pedigree in Görbe’s paternal background has allowed for ‘apple fallen far from the tree’ interpretations of her television celebrity, recalling the discursive value hierarchy between entertainment television and art cinema. The series mobilises this background via intertextuality: Linda lives with her actor father (Gyula Bodrogi), who as a mediocre ham performer forever stuck with third-rate (often TV) roles, is the direct opposite of the kind of acting culture with which Görbe’s own father is associated.

But this brief outline of Linda‘s most luminous features and production background still only scratches the surface of both the series’, the characters’, and Görbe’s own positions as outlandish, unsettling outliers in their respective contexts. Linda was an unprecedented success both domestically and internationally East of the Iron Curtain (Pavlova 2016), thanks to its calculated mixture of recognisable and novel features, which in isolation may be familiar from the era’s different media cultures. These include the upbeat Jazz-Funk theme music composed by jazz musician György Vukán; the offbeat iconography of the opening and closing sequences; the female detective’s embodied difference and liminal position in the police force; recurring motifs such as her yellow Babetta moped, loud-coloured outfits, signature battle cry, and ritual of silently stepping out of her clogs before a fight; the meshing of ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern European’ genre tropes; and the deployment of ironic intertextuality mobilising recognisable local faces and cultural milieus.

Yet, if Linda is an idiosyncratic addition to the pantheon of television’s female detectives, her significance cannot be explained by a supposed uniqueness within, and challenge to, Soviet satellite nations’—putatively homogenous—media environments. Rather, this article argues, it is more productive to engage with how the series’ seeming idiosyncrasy emerges precisely from its time and place. As I will show, this makes Linda and Linda fitting ‘misfits’ in Garland-Thomson’s term, that is, productive agents of an incongruent yet apposite relationship between body-text and environment in material, spatial, temporal terms. (2011: 592-593) We will see this productive misfitting on the levels of embodied characterisation (the late-socialist female action superhero/detective), genre hybridity, and the portrayal of crime through both national(ist), transnational, intertextual and intermedial discourses. But again, it would be a mistake to interpret these misfittings as consequences of geopolitical origins, that is to say late-socialist media’s supposed limitations, but of more complex transcultural, regional and domestic processes which allow for Linda’s misfitting to fit precisely into her cultural context. Through close textual analysis of both the series and Linda as a figure, the article also demonstrates the necessity to consider how national, regional and transnational discourses influence television’s expressive modes (Mihelj 2014), an approach that challenges recent feminist scholarship on crime television. In particular, Linda’s existence upsets dominant Anglo-American academic theorisations of the transnationally popular female sleuth, both in her historic and contemporary incarnations, as will be shown. In the following, I first sketch this scholarly background, then examine the series’ production of the character as productive misfit in Garland-Thomson’s term, by focusing in turn on the series’ expression of gendered transnational intertextuality, Linda’s misfitting femininity, aspects of genre hybridity, and discourses of nation(alism).

The Transnational Female Detective in Television Scholarship

While Anglo-American and Western European feminist television scholarship has theorised the effects of the female detective’s growing presence in the medium’s crime genres since the 1970s and 1980s as responses to Western feminist discourses, this literature (often admittedly) ignores Eastern European media cultures’ relationship to this development. The question of transnational/-cultural interaction beyond Anglophone cultures has only recently gained traction thanks to the influence of Nordic Noir on Anglo-American crime drama. (Coulthard et al. 2018; Klinger 2018) For much of this literature, even Australian and Scandinavian television exist on the ‘periphery’ of global TV culture (Turnbull & McCutcheon 2020: 200), which leaves little space on this academic map for media industries that are ‘peripheral’ not only for their geographic, but also geopolitical and linguistic positions in relation to the global West’s cultural centres. This historic neglect generally characterises media studies; as trailblazing scholar of post/socialist media Anikó Imre shows, until recently Anglophone television scholarship’s interest has been confined to Anglo-American and Western European cultures (2016: 2; see also Mihelj 2014: 8), and such academic discourses implicitly code the term ‘European television’ as ‘Western European television’. (Havens, Imre & Lustyik 2012: 2) Despite some gestures towards decentring Western Europe, even more recent studies of ‘global’ TV (Shimpach, 2020) and trans-European crime television ignore, or only sporadically include, Eastern ‘peripheries’ as European cultural production’s exotic other. (e.g. Toft Hansen, Peacock & Turnbull 2018; see also the ‘Detecting Europe in Contemporary Crime Narratives’ research project)[2]

Simultaneously, studies of the Eastern European region’s media history have until recently tended to ignore television (exempting communication studies’ examinations of news journalism and media systems in their transformations pre- and post-1989, as argued by Mihelj (2012: 14)), rooted in an enduring suspiciousness toward the medium’s entertainment function, and ‘following a Eurocentric hierarchy of high and low culture also embraced by Eastern European intellectual and political elites’. (Imre 2016: 4-5) The elitist hierarchization to which Imre refers is typically exemplified in the prioritization of (art) cinema at the expense of mass entertainment television in Eastern European media historiography. (Imre 2016: 163) It is in the nexus of these academic neglects that televisual flashpoints such as Linda disappear from interpretations of European crime TV’s gendered histories, since lacking organic considerations of Eastern European TV history, old Cold War clichés of the region as a cultural space of ‘scarcity, homogeneity, and brainwashing’ endure to fill in the blanks. (Imre 2016: 7; see also Mihelj 2012 & 2014: 9-11) And while some isolated and brief attempts have been made to consider Linda as an example of late socialist entertainment television and its relationship to gender and policing (Imre 2016: 218-219; Zsámba 2014), the series needs to be paid closer attention, not only in the ways it reflects late socialist television’s ideological transformations, but also to demonstrate its complex ambitions of joining, challenging, and adding to both national(ist), regional and transnational(ist) popular discourses on televisual genre hybridity and gender, projected onto the female detective figure. Thus, what I hope to show is that the series is an object lesson for at least two, artificially bifurcated, strands of media scholarship: Anglo-American and Western literature on crime TV and the female sleuth, and scholarship engaged with Eastern Europe’s gendered television history.[3]

As I argue, following Imre’s (2016: 12-19) and Mihelj’s (2012 & 2014) work on the region’s significance for transnational television historiography, Linda demonstrates not only the historic permeability of Eastern and Western Europe’s media cultures, but also traditions of transcultural, regional travel across socialist nations’ TV products themselves (Imre 2016: 12; Havens, Imre, & Lustyik 2012: 4; Mihelj 2014: 14-16)—and the influence of these travels on mediating gender. For a popular account of the latter, consider Bulgarian journalist Yoana Pavlova’s (2016) praise of Linda as a site of cultural memory and lucrative export across the region, the heroine’s ‘signature squeal and the corny sound effect from her punches reverberat[ing] from every corner of the Eastern Bloc’ (more on that squeal and those punches later). Pavlova understands Linda’s transcultural value not only as exportable late-socialist television, but also as a product of Western aspirationalism within the region: ‘we socialist kids did not really care about the plot—we used to watch Linda as a showcase of a lifestyle and attitude we could not afford. From the cars and the boats, to the colourful knitwear and the memorable batik-dyed skirt, Hungary grew in our imagination as a promised land where things looked almost western and police work could be cool‘. (Pavlova 2016) The touristic, consumerist gaze Linda casts upon Hungary is an aspect to which I will also return for its significance in creating the detective superheroine. But it is worth noting that Pavlova’s anecdotal reminiscence of Hungary as space of quasi-Western coolness projected onto the female superhero resonates with familiar Western imaginaries of the region, which see the Balkans and nations like Romania as the ’primitive East’ while ‘Budapest or Prague [are considered] shinier places that have more confidently erased their communist past’. (Bardan & Imre 2011: 169)

Linda could then be filed away as evidence of the efforts of a Soviet satellite nation located in convenient proximity to the Iron Curtain’s Westerly border to Westernise, in this instance in emphatically gendered terms, by producing a cool superheroine in many ways similar to Anglo-American ‘feminist’ media idols. But this would not fully explain the modes of transcultural, regional, intertextual and intermedial play in the detective heroine’s emergence, nor her significance as a gendered misfit. In the following section, I examine Linda’s figure through these contexts, and in order to illuminate their relevance, I approach them by using the title sequence and theme score—both enduring signifiers of the series in cultural memory—as entry points. I am motivated to use these by the sequence’s clear ambition to encompass the series’ generic-thematic hybridity, and Linda’s own misfitness and superheroism, all shot through with playful nods to ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern (European)’ popular media. In using the credit sequence as entry point for analysis, I am also indebted to Kathleen McHugh’s approach which sees title sequences as paratexts that are key to understanding a series’ meaning-making efforts, since they ‘connect and partake of both the programs they introduce and their commercial, cultural, and industrial context’. (2015: 17) Given the consciously designed iconicity of Linda’s title sequence, the popularity of which spans socialist and post-socialist eras, such an approach seems particularly apt.

Trans/national, Regional Intertextuality & Gender in Linda

Let us start with that theme music. Evidencing the enduring popularity of Vukán’s score not as ironic post-socialist nostalgia but vintage cool for post-millennial urban music scenes, the Hungarian alternative label Budabeats Records released an album in 2015 that contained versions remixed by contemporary DJs. The album website describes the original as ‘classic 70’s funky crime-jazz style (á la Lalo Schifrin, Quincy Jones, etc.), very unusual for communist Hungary especially with such a rich orchestration’. (‘Linda Remixed’ 2015) The mention of 1970s crime funk-jazz offers an entry point into the series’ transnational gender politics: inspired by contemporaneous American crime procedurals, the score is more in the vein of The Streets of San Francisco’s (1972-77) rhythmic, percussion- and bass-heavy, masculine funk-jazz theme, than scores typical of the era’s women-helmed detective, superhero and action series like The Bionic Woman (1976-78), Police Woman (1974-78), Charlie’s Angels (1976-81), Wonder Woman (1975-79) or Cagney and Lacey (1981-88), which tend to apply string-dominated, mellower motifs with more feminine connotations. Another layer to the theme’s funk-jazz cool is the added sound effects that contribute to its dynamic vibrancy, saturated with a large dose of tongue-in-cheek: Linda’s signature (and much-ridiculed) falsetto battle cries, the equally high-pitched sounds of a police whistle and siren, and, contrastingly, a male choir rhythmically crying out ‘Linda!’ The latter recalls the 1960s-70s superhero series’ musical trope of shouting out the superhero’s name—think Wonder Woman and Batman (1966-68). This link signals the layers of Linda’s transcultural intertextuality: American forerunners use this sonic trope to conjure the shows’ comic book genesis, since the shouts typically accompany the credits’ visual allusions to the original cartoon characters. But Linda has no such extratextual comic origins, rather, as we will see, the credits create them to link her to this tradition, condensed into one, second-long action. But even if Linda plays with the notion of a Hungarian comic book superhero of fantastic proportions, it limits this to extradiegetic play without weaving it into the diegesis: lacking split identities, secret lives or complex superheroic origins, Linda’s is a harmonious identity. She is only an exceptionally skilled fighter surrounded by a (mostly) adoring ensemble of colleagues and family members: the predominantly male cop colleagues, her clumsy, effeminate fiancée Tomi (Béla Szerednyei), her widowed father Béla, and Béla’s next-door-neighbour/girlfriend Klárika (Ildikó Pécsi). Importantly, the series’ aesthetics deploy a mode of realism with an ‘Eastern European,’ homely feel (long takes, handheld camera, location shooting, improvised-sounding comedy banter) that mostly keep the visual tropes of fantasy genres at bay, even though the heroine is an over-the-top fantasy of gendered wish-fulfilment. This contrast between fantastical American superheroes and this Eastern European kitchen-sink-realist equivalent is tasked to express a conflicted—aspirational and self-deprecating—relationship with Western cultural imperialism and myths of Americanness; a relationship integral to late- and post-socialist nationalisms. Linda may not be as fantastical as her American counterparts, but she is ‘ours.’

But, as noted, this ‘realist’ superheroine does get a science fiction/comic book origin in the opening credits, which achieve their iconicity by mixing live action with animation, though these are closer in style to the era’s Polish and Hungarian poster art and advertising culture than to American comic book iconographies. This mixture embeds Linda‘s credits in the tradition of Eastern European media’s ‘avant-garde creations [which] were often abstract and even absurd’ (Imre 2020: 389), and which re-imagined Western media products for domestic audiences. The title sequence starts in an animated science fiction space, the camera fixed as stars and meteors shoot past it. The Hungarian national television logo (MTV) zooms into view, á la the star destroyer in Star Wars’ (1977) opening, and disappears into the distance. Next, a large egg-shaped Earth floats into the centre of the image, slowly spinning on its axis. Whooshing ‘space’ sounds accompanying the sequence establish the feel of cosmic equilibrium, its seriousness harnessed by the aminated-cartoon imagery. The Earth-egg rests/spins there for a beat, to be suddenly destroyed from the inside: a white karate suited, live-action Linda kicks her way out of it spread-eagle style, accompanied by her long, signature ‘Ya!’ scream, and is freeze-farmed in this position as cartoon eggshells fly around her. (Figure 1) The freeze-framing carves the image into the viewer’s mind, resonating with—perhaps parodying—Eastern European science fiction culture that transplanted Western blockbuster cinema’s visual iconographies by reimagining them as heady, bizarre poster art. Linda is thus born by bursting out of the Earth-egg; only now do the first beats of the crime-funk score kick in as the credits’ proper start.

This kick-start makes overdetermined statements: at each episode’s beginning, Linda gives herself a violent parthenogenetic birth in playful reference to both Star Wars and Alien (1979; released in Hungary in 1981 to massive success as the first modern Hollywood horror blockbuster to get wide release in the country). But if hers is an alien presence that disrupts a cartoon universe’s equilibrium, its monstrous femininity, in Creed’s influential term (1993), is replaced with a celebration of youthful female destruction/disruption, since the rest of the credits emphasise Linda’s dynamic, confident, comfortable inhabiting of the role of superiorly-skilled misfit. Notably, in the credits’ mixture of live-action and cartoon footage, she is the only one malleably turning from one visual rendering to the other, often in the middle of dynamic movement, making outsized leaps, and appearing as a cartoon figure in odd spaces, such as her police chief’s giant, live-action pipe (signifier of old-school, Sherlock Holmes-style detecting). This signals another feature delineating the character as late-socialist superwoman: her ability to fit into, yet stand out from, most social contexts (as discussed below). The second-long explosive opening then heralds both the novelty of (masculinised) femininity in otherwise masculine genres, and also that the most memorable feature of her strangeness is her mastery of martial arts (rather than, for instance, her detecting skills), of which we get some teasers in the opening via isolated live-action demonstration footage.

Linda as the Misfitting Superwoman in a Trans/national, Regional Context

Beyond the sheer outlandish idea of a Taekwon-Do master ‘detective girl’ (as she is often described), Linda goes to even greater lengths to hammer home that her very existence is alien. The signature squeal is one such, sonic, signifier. The iconicity of the Earth-egg’s explosion cannot be separated from its sonic element: just as the Earth-egg’s shattering visually destroys the space-time continuum, so does Linda’s elongated, high-pitched scream shatter the soothing aural atmosphere. A key signifying motif of Linda, her squeal has been preserved in cultural memory, both as stuff of ironic nostalgia and as an annoying, grating, ridiculous (feminine) noise. As such, this is one contradictory aspect of the series’ place in the Hungarian TV pantheon. While a callback to Bruce Lee’s high-pitched yells formulated as a means of seeking legitimacy through metatextual reference, coming from the body of a small woman such screams are typically associated with the context in which women tend to scream onscreen: in their role as horror cinema’s female victims. As Marie Thompson notes, drawing on Michel Chion, in cinema ‘the scream is depicted as a particularly feminine phenomenon,’ signifying excessive, out-of-control emotion, chaos, victimhood; ‘femininity at its most vulnerable’. Contrastingly, male yelling usually connotes mastery and power. (2013: 151) Linda’s high-pitched scream is uncanny-ridiculous precisely because it uses the sonic register of raw feminine vulnerability (it is much higher than Lee’s screams). Yet it functions as the battle cry of martial arts, that is, as ‘affective scream’ in Thompson’s term, emitted not to express affectedness but to tactically create impact: to intimidate. (Thompson 2013: 154-156) The sound‘s gendered connotation, and its pragmatic, controlled application stand in bewildering contrast, accounting for the diffuse responses to it. The voice, and the sonic element of femininity, bear on Linda’s endurance in a less calculated, extratextual detail as well: audience discourses critical of Görbe’s acting often reference her speaking voice, evoking in their dismissal discussions around Linda’s diegetic scream—annoying and grating—as evidence for Görbe lacking acting skills, and as one aspect of her mis- or unfitness in relation to older, veteran actors in the cast. Linda and Görbe’s grating presence become projected onto the voice as carrier of misfitting.

As indicated, fight sequences are of especial importance to Linda, used in episodic television’s ritualistic manner: episodes open with a vignette of Linda running into a group of male hooligans who start picking on her, culminating in combat. Further fights follow during her investigations, and the episode ends with Linda defeating the crime plot’s villains on her own, handing them over to her notoriously late-arriving cop colleagues. The opening fight is diegetically isolated from the main investigation, but might introduce themes underlying it; its main function is to display physical-athletic skills and visual spectacle. If Linda differs from her Western cartoon-originating superhero(ine) predecessors in her backstory realism and the series’ realist filming methods, the fight sequences do constitute a bubble of stylisation emulating the era’s martial arts films (rapid cuts, zoom ins/outs, whip pans, slow-motion displays of technique). And while for Western postcolonialist eyes such use of Taekwon-Do and martial arts movie styles might constitute a special case of Orientalism that both appropriates East Asian references and further posits Linda as a misfit or Other in her cultural context, such a reading would ignore the local, regional complexity of fight genres’ travel to and popularity in Hungary. Two influences need to be considered here: first, the obvious transnational flow of East Asian martial arts genres hallmarked by Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan films, themselves strategic blends of Hong Kong and Hollywood production cultures with an eye on the global market. Second, the influence of 1970s-80s Italian crime parody/buddy comedy films starring Carlo Pedersoli and Mario Girotti, under the stage names Bud Spencer and Terence Hill, is vital. The Spencer-Hill double act featured trademark comic fight scenes and Spencer’s ‘hammer swing blows’ (Broughton 2016: 155), accompanied by parodistic-corny sound effects similar to Linda’s, and was widely popular in both German-speaking territories and Hungary. (Heger 2009) The latter is measurable by the fact that István Bujtor, the Hungarian actor who provided the dub of Spencer’s voice, produced and was the star of the ‘Ötvös Csöpi’ movie series starting in the late 1970s, which emulated the duo’s signature style of crime and fight comedy, and whose impetus was not only Bujtor’s dubbing of Spencer, but also their physical similarity. As such, Linda as crime/fighting series blending visual spectacle and parody arrived into a cultural space for which complex transcultural, transnational, and regional blendings/emulations/embeddings of martial arts and comic fight crime genres were already familiar, and not at all alien. Considering such specificities of the local context, it becomes even more significant that the series signals its novelty and difference by the dual methods of transplanting these popular genres of cinema to television, and simultaneously gender-bending the fighting hero.

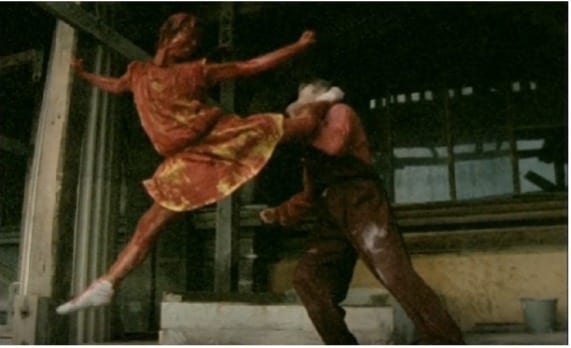

A memorable example of martial arts movie-inspired stylisation in television’s expressive modes, highlighting Linda’s confident yet jarring misfitting through display of fight, is the opening of the episode Piros mint a kármin/Red like Carmine (2:3). The sequence also illustrates each episode’s thematic-stylistic coherence: while narratively isolated, the vignette introduces the story’s main theme, in this case the world of painters and painting, through Linda’s visual rendition. In this opening, she beats up a group of construction workers on a scaffolding who cat-call women walking past underneath. Linda, as one of the harassed women, calls back in challenge and immediately displays kinetic skill as she catches a beer bottle dropped on her. Then another cat-caller spills a bucket of red paint on her head, the camera tracking in slow motion as she becomes drenched in the blood-coloured slime in a visual recall of Carrie (1976). Unfazed, Linda beats up the workers, the footage creating bizarre, slow-motion images of her paint-covered figure mid-fight. (Figures 2-4) The display of martial arts technique is rendered visually eerie through the use of colour, and in conjuring the Carrie imagery (additionally, she is wearing a frilly, initially yellow mini-dress). But once again, the fantasy of female monstrosity through out-of-control power is re-imagined as mixture of playful reference and in-control female competence, while continuing to signify striking difference. The next scene takes place in Linda and her father’s home: she shows up grinning under the red paint and gives him a jump-scare, having presumably walked across town with this look, without bothering to wipe the paint off. (Figure 5)

Similar to the Alien reference, the programme’s knowing use of Western fantasies of destructive, horror-coded femininity is remarkable not, as might be presumed, for such fantasies’ supposed transnational status as deterritorialisable ‘lingua franca’ (see Klinger [2018] on crime noir’s exportable trope of the white female victim), that is, cross-culturally recognisable motifs ready to be recycled in other national contexts.[4] Rather, I argue, it is the modes of seeing, selecting, adapting, and incorporating these into the national-cultural context from the Hungarian vantage point that helps us better understand the significance of television’s transnational and regional flows, and their nationally-specific domestication processes through this example. Here, the cultural context in which these notions of mediated femininity are re-imagined is one that conceives of female power in the terms of what Imre calls socialist superwomanhood, and to which I now turn to further couch Linda’s meanings in their national context, and interrogate the cultural fittingness of her misfitting.

In her pioneering work TV Socialism (2016), Imre discusses how socialist television mediated these regimes’ gender politics which, while refusing Western feminism, conceived of women as key agents of socialist citizenship both through domestic labour and, to some extent, their role in the workforce. (Imre 2016: 197-198) Thaw-period socialist television overwhelmingly represented women in contemporary, realistic settings, most typically in the ‘socialist soap opera,’ as multitasking, often independent, competent, flexible participants in socialist life. Imre sees Linda as an extreme version of this mediated socialist superheroism, emptied of political messaging (2016: 218), that for her presages a future of post-socialist postfeminism dominating the region’s gender politics in the 1990s (2016: 224). Yet while in this reading Linda fits into its era’s TV culture on the grounds that she is yet another (albeit extreme, thanks to Western genre tropes) socialist superwoman, this does not fully account for the text’s overdetermined use of uncanniness and misfitness in Linda’s figure, which were missing from late-socialist drama’s configuration of over-competent womanhood. And notably, Imre discusses Linda in a chapter on socialist soap operas, listing this as one constituent of the series’ genre hybridity. But while Linda does concoct a bizarre cocktail of genres, soap or domestic melodrama is decidedly missing from these. One of the series’ remarkable characterisation methods is the utter lack of conflict in Linda’s identity, replaced with poise and presence of mind both in domestic settings (she looks after her widowed father lovingly, and has a teasing, settled relationship with her fiancée) and workplace (she is self-confidently always steps ahead of the cops in solving crimes). Yet it is this poise that the series uses as an enduring, episodic source of light conflict, as her environment constantly struggles to turn her away from policing and fighting as something unbecoming for a young woman. But as an effective pillar of meaning-making, the theme of Linda’s stubborn insistence on becoming a cop is rendered a conflict solely through comedy television’s ritualistic joke-apparatus nature, not through the soap’s serialised seriousness. As such, while the viewer is invited to share Linda’s frustration with her environment constantly trying to thwart her efforts to excel in law enforcement (since the text unequivocally posits her as the best police), part of the series’ pleasures are the comic situations deriving from the incongruity between Linda’s over-competence and her incompetent environment’s insistence that she is the problem: incompetent and misfitting. Rather than dramatic, evolving, serialized conflict, this dynamic is a comic constant of the series, recalling Feuer’s theorisation of episodic television. (see Note 1 below) In addition to sci-fi and martial arts, it is the intertextual comedy and crime procedural/noir/cop show genres through which the series further articulates Linda’s misfitting superwomanhood. In the following section, I explore these latter genre modalities, and continue to use the title sequence to unpack their mobilisation.

The Ambiguous Comedy of Linda’s Misfitting Femininity

The title sequence features references to Linda’s domestic and professional lives, all infused with Taekwon-Do training as cool fighting skill and exercise. After the Earth-egg’s destruction, slow-motion footage of Linda and Tomi running through a forest in a training session is followed by the two embraced in a long close-up kiss. While the running footage, with Linda in front, evokes the trope of a woman running through the woods in gendered danger—misleading imagery used in a similar capacity by the opening of The Silence of the Lambs (1991; Tasker 2002: 22)—its potential signification of anxiety is immediately shut down by the next image of the pair mid-makeout. Not only does this defuse the sense of danger, but it also confirms Linda’s heterosexuality—albeit with some ambiguity, since the two sport curiously similar mullets. The romantic relationship underscores the gendered ambiguity of this pairing, with Linda occupying the masculine (active, clever, level-headed, fight-happy, heroic) role, and ‘incessantly mock[ing] her puppy dog boyfriend and exploit[ing] him for various services she requires for her detective missions’ (Imre 2016: 218), while Tomi brings comic incompetence and whininess into the dynamic. And although Imre calls him Linda’s ‘boyfriend,’ their relationship is always described as ‘fiancée,’ a position signifying yet another small but significant ambiguity: forever in the limbo state of engagement, Linda is not a married woman (escaping media trappings of that role connoting as it does domesticity) yet semi-fixed in heteronormative coupledom.

If Tomi’s role is part-romance, part-comedy, the latter mode dominates the rest of the ensemble cast, of whom widowed father Béla and neighbour/girlfriend Klárika get their own quirky introductions in the opening, which playfully nod not only to their diegetic position, but also to that of the two actors in Hungarian media culture. Béla, the short, balding, pudgy ham actor stuck in mediocre TV and film roles, and Klárika, his large, tall, husky-voiced, dark-haired, lustful partner, are one axis of the series’ use of situation comedy. This draws on Hungarian film and cabaret traditions of the small comic everyman/large pining woman pairing, seen for instance in the Gyula Kabos-Ella Gombaszögi duo of 1930s Hungarian film comedies. In this pairing, Klárika’s erotic longing for Béla and its forever deferred consummation turns ex-sex symbol, middle-aged Pécsi’s previous star persona (‘the Hungarian Gina Lollobrigida’ [Anon. 2020]) into frustrated sex comedy, which evokes Gombaszögi’s heritage with especial force since both characters’ unfulfilled sexuality is often linked with outsized culinary appetite. (for Gombaszögi’s star persona see Gergely 2016: 262) The credits refer to her star text through yet more absurdist footage: after a cartoon sequence of Linda scaring off an American car by jumping in front of it from a hilltop (with the leap depicted as outsized-superheroic), the image of the turning car shot from between Linda’s bare ankles cuts to Pécsi’s real-life headshot displaying a suggestive, pursed-lips expression, accompanied by a slurping sound. The editing uses an effect that makes the Linda-image look as if it is being slurped up into Pécsi’s mouth. (Figures 6-7) Another slurping sound and editing effect turns Pécsi’s image into live-action Linda riding her moped on the hilltop.

This contrasting (cartoon and live action; agile, slim Linda and sumptuously big-mouthed, big-haired, big-bodied, static Pécsi) telegraphs an embodied dyad of femininities, driving at the supposed novelty of Linda’s sporty, vigorous new womanhood. Pécsi’s casting and allusions to her 1960s-70s star text—now expired, matron-like, and as such the stuff of comedy—play a key part in establishing this new, youthful womanhood. This contrasting of embodied—new and old, ‘Western’ and ‘Hungarian’—femininities also aligns Linda with discourses of gendered nationhood which fascinated Hungarian media in the 1980s as Western liberalisation was underway. Fictional Linda’s case can be juxtaposed with that of Csilla Molnár, winner of the 1985 Miss Hungary beauty contest, whose slim, tall femininity created media buzz around how ‘her physique was uniquely ‘European,’ as such discordant with Hungarian beauty ideals of the time’. (Havas, forthcoming) The corporeal contrast between Görbe/Linda and Pécsi/Klárika signals, in similarly feminised terms Hungarian cultural anxieties about aspirations toward mythical Westernness, yet pride in national traditions (of embodied femininity) as cultural difference.

The episode Erotic Show (3:4) further nuances the putative alienness of Linda’s embodied femininity. The recurring schtick of most episodes’ detective plot involves Linda going undercover successfully in the story’s cultural-professional milieu, where, per Imre, this success signals her flexible superwomanhood. (2016: 218) Plots of undercover work highlight her ability to improvise and excel in any given environment or profession ( for example: operetta singer in Oszkár tudja/Oscar Knows, 1:3; doctoral student of Hungarian history in Panoptikum/Waxworks, 2:5; computer coder in Software, 2:6; entertainment journalist in Pop pokol/Pop Hell, 2:7). Storylines also showcase her extraordinary athletic-acrobatic skills. In A tizennyolc karátos aranyhal/The Eighteen Carat Goldfish (2:1) she takes an acrobatic dive into a pool from a spring-board having just beaten up a band of hooligans who tried to rape her; in Pavane egy infánsnő halálára/Pavane for a Dead Princess (2:2) she goes undercover as a ballerina at the ballet troupe of Pécs; in both Red like Carmine and Víziszony/Hydrophobia (3:1) she swims across the Danube river; in the latter she also learns scuba diving and beats up the villain underwater in diving gear. It is in this contrast that her relative failure at undercover police work in Erotic Show gains its significance: in one of the few instances where the job is linked to sex work, a sleazy club owner refuses to add Linda to the chorus line, deeming her ‘a rake of a woman’ plus too underage-looking; implying that the local male clientele finds this female body type undesirable. Linda’s embodied misfitness of femininity as national difference is made explicit here, while the text constantly celebrates this body’s over-competence in terms of physical fitness, which helps to her solve crimes and defeat undesirable elements of Hungarian society, and thus to fit in.

Let us now turn toward the father, played by beloved comedy actor Bodrogi, whose addition to the ensemble channels Linda’s articulation of the detective superheroine as productive misfit by way of bringing in comic intertextuality. The credits’ playful shorthand for his familiarity is another bizarre method of introduction: Bodrogi’s cartoon face looks at us through cross-hairs á la James Bond, while the choir excitedly shouts out the actor’s name: no other cast member receives this treatment. His extratextual recognizability confirmed, cartoon Bodrogi takes a bow with a sarcastic smile, then pulls the cross-hairs away with his finger, like a cobweb. But while he plays an actor here, a key intertextual running joke is that instead of the popular star Bodrogi was at the time—and which the credits invoke—Béla is archetype of the ridiculously unsuccessful ham actor, cast in small parts while nurturing outsized delusions of grandeur about his acting chops and fame (as discussed, this reverses the extratextual context of Görbe’s own paternal heritage). Using Bodrogi as small-time, struggling actor allows Linda to offer self-referential backstage peeks at the Hungarian cultural industries, and through this playful intertextuality assert cultural legitimacy and relevance akin to American ‘quality’ television’s contemporaneous strategies. (Havas forthcoming 2022) Simultaneously, this allows the show to retain the comic-pitiful everyman figure of Eastern European Jewish comedy traditions—one running joke involves Béla’s different small acting jobs in each episode, such as dubbing an extra in a Soviet war movie or a deer in a cartoon, and roles in adverts and historical TV dramas. While this intense, ironic intertextuality is nothing new in Hungarian TV production (Imre 2016: 148-153), Linda‘s winking self-reflection uses it less as political satire than as further conveyor of the female superhero as popular, exportable fantasy.

Of note is the episode Waxworks, which is full of intertextual references to contemporaneous film and TV cultures, as well as to Budapest as a metropolitan space of vigorous cultural life. In the opening, Linda beats up ticket scalpers outside Filmmúzeum, Budapest’s beloved art cinema of the time. Later, the police uses the iconic TV reality crime chat show Kékfény/Blue Light (1964-) to circulate suspect sketches on television, which allows for footage of this show’s production, and ironically signals harmonious cooperation between socialist law enforcement and television. The crime plot takes place at the waxworks museum inside the catacombs of the Buda Castle Labyrinth, and references are made to a historical film being shot there. Linda gets involved through Béla: a cast of his face is to be used in the creation of a historical figure’s wax sculpture, and the episode revolves around the waxworks exhibition’s international travel being used by the villains for smuggling Hungarian medieval jewellery to the West. The story showcases (and renders eerie) the exhibited waxworks via several guided tours the central characters visit in the catacombs, with the tour guides explaining the figures’ significance in Hungarian history. These visits bookend the episode, and the final tour ends with the guide pointing out the latest addition to the collection as part of modern history: ‘This final waxwork portrays Budapest’s, Hungary’s, perhaps even the whole world’s fastest and most formidable police girl… Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the Buda Castle exhibition’s newest acquisition: Linda.’ At this, we see Linda’s waxwork: wearing her signature yellow raincoat, she is portrayed mid-air fly-kicking an opponent, as visitors gasp in awe. (Figure 8) Among them are the full ensemble cast exchanging knowing smiles as the camera cuts back-and-forth between Linda’s waxwork face and the original. Winkingly adding fictional Linda to Hungarian history’s pantheon of national, exportable, (male) heroes, the programme both anticipates and sends up late-socialist countries’ nationalist projects of Western aspirationalism and post-socialist nation branding through Eurocentric appeals to historical greatness. (Bardan & Imre, 2011)

Nation & Femininity in Linda as Urban Crime Procedural

Waxworks’ use of the Buda Castle Labyrinth’s catacombs and waxwork exhibition as both tourist landmarks and also uncanny, gothic, dangerous spaces, points us toward Linda‘s final key generic feature: its mixture of the noir/cop procedural with the touristic gaze cast upon urban locations of crime. Let us return again to the title sequence and its introduction of Linda’s boss, Major Eősze (Gábor Deme, Tamás Vayer), whose figure transplants the genre trope of the strict-yet-just police chief into the Hungarian context. As mentioned, his introduction highlights Linda’s incongruity in the police force: we see a large live-action profile photo of Eősze with his signature pipe hanging from his mouth. A tiny cartoon Linda walks around the pipe’s brim and falls into it. The pipe is then turned upside down and cartoon Linda falls out as tiny cartoon hearts float around her. This sequence plays up both Linda’s mischievous, impish, girly misfitness in the world of policing, and the jovially paternal/istic relationship between Linda and Eősze, who is the series’ most viable representative of male authority. Yet if Eősze resonates with the archetype of the gruffly loving father figure for the young heroine, the effectiveness of his paternal, authoritative care is significantly curtailed by the portrayal of the police as unsuccessful at detecting.[5] Bar Eősze, the primarily male members of the force are shown through the region’s antiauthoritarian traditions of the cop joke; that is, as stupid buffoons, played by Hungarian comedy stars known for their schlemiel figures (Gábor Harsányi, Péter Balázs).

In her examination of Linda as successor to Anglo-American hard-boiled literature’s female sleuth, Renáta Zsámba (2014) discusses the programme’s reflection on the socialist regime’s relationship to representing crime and detectives. The enduring notion is that these were difficult to depict, since both individualism and the idea of crime in a collectivist, socialist society were incongruous with the ideology. For Zsámba, Linda’s success, aside from late-socialist Westernisation, can be attributed to both the use of femininity, which channels individualism through the novelty of the hard-boiled female detective, and to portraying villains as enemies of the socialist ethos: Western foreigners, Hungarian dissidents to the West, and members of an old-world moneyed Hungarian elite living in the villas of the Buda side of the capital. (Zsámba 2014: 136). Further, the hooligans Linda beats up each episode ‘who either want to mug or harass her … gave an opportunity for the state to show the people what is the right way of using spaces and what is not’. (Zsámba 2014)

Zsámba’s interpretation is a mixture of factually wrong, and neglectful of the contexts both of (late-socialist) television and several key elements of Linda that inform its portrayal of crime. Regarding factual misinterpretation, while there are examples of the kinds of villains Zsámba posits as most typical of the series, they do not dominate it. Rather, in a recurring trope, criminals tend to be Hungarian representatives of local cultural life and specialist professions (Pavane…, Red like Carmine, Waxworks, Software, Pop Hell, Hydrophobia, Aranyháromszög/Gold Triangle [3:2], Stoplis angyalok/Angels in Soccer Shoes [3:3] etc.). In the memorable case of The Eighteen Carat Goldfish, the bad guys are a group of young Hungarian men hunting for, and gang-raping, young German tourists on Margit Island, another touristic landscape of the capital. This episode employs gendered gothicisation similar to Waxworks’ use of catacombs and wax statues: in one scene, the gang chases Linda into a deserted, decaying part of Margit Island’s outdoor swimming pool, visually re-coding this popular public location as unsettling and dangerous. Goldfish is remarkable also for openly mobilising the series’ ever-present subtext: that the threat of sexual violence follows Linda everywhere in her investigations, and often occasions the episode-opening fights, seen for instance in Red like Carmine. This is of course integral to the language of female-centred crime narratives, but in this context, it cannot be divorced from the series’ representation of Budapest and its effect on its portrayal as a cool, culturally buzzing European metropolis in which modernity (including Linda’s new womanhood) and history harmoniously coexist. The opening credits’ final few seconds certainly convey the latter: as the live-action/cartoon sequence ends and the funk-crime theme fades out, a short montage sequence bridges the credits with the episode start. This montage shows Budapest’s hallmark statues and monuments (the lions of Chain Bridge, the Millennium Monument of Heroes’ Square, the Liberty Statue of Gellért Hill) to the tune of solemn, pathos-filled orchestral music. But these cues to the city’s grand architectural history through prestigious old monuments are showcased via the visual language of the martial arts movie, that is, by using whip pans and snap zoom-ins/outs. While this signals Linda’s ambition to show Budapest as a centre of European history seen through postmodern, cosmopolitan eyes, and thus to drag it out of the darkness of the socialist past into the light of a cool, Westernised present, Linda’s emphatically gendered adventures among these landmark public spaces, and the overwhelming maleness of the villains, complicate this reading. Most episodes open, after the ‘monuments’ montage, with aerial shots of an emblematic public space providing a backdrop to Linda’s lonely fight against a collective of hostile men (in Aranyháromszög/Golden Triangle [3:2], for example, she beats them up outside the Parliament building). The programme’s episodic-ritualistic structure renders the touristic gaze ambiguous: while reassuring that Linda will always triumph against male aggressors, episodic TV’s repetitive apparatus also suggests that male (sexual) violence is just as much a part of the fabric of this charming modern metropolis as its grand statues (of male historical figures), however vigorously Linda works on eradicating it. It is the sexualised nature of the threat of male criminality and the effect of episodic television that Zsámba fails to consider in concluding that the series’ treatment of street hooligans propagandistically instructs the viewer of the proper usage of public spaces.

The treatment of crime plot villains is just as ambiguous, and complicates the ‘socialist propaganda against foreign threats’ reading. As I have noted, villains are often members of modern Hungary’s intellectual, cultural, professional middle class; and crucially, the nature of the crimes often has less to do with a compromising Western influence, and more to do with a domestic misuse of exportable Hungarian resources. A roster of crime plots revolves around Hungarian criminals smuggling to the West the country’s historical (Waxworks, Rebeka [2:4], Hydrophobia), artistic (Red like Carmine, Pop Hell, Golden Triangle), intellectual (Software), or commercial (Oscar Knows) properties. Implied in this is these properties’ superior value in capitalist Europe. In the use of both smuggling and sexual violence (spoiling local touristic goods and spaces; in Goldfish, via sexually abusing German female tourists who visited this supposedly Westernised, i.e. civilised capital in good faith), criminals are imagined as locals exploitatively abusing the ongoing project of Western aspiration—and it is only Linda’s new, violent, flexible superwomanhood, as opposed to the police force’s traditional methods, that can (temporarily) stop them. This is where the misfitting, fighting detective girl fits into her space and time, self-confidently inhabiting a transitional Hungary in search of a future post-socialist, transnational, cosmopolitan identity. The series’ closing sequence, matching the opener in its iconicity, literally shouts from the rooftops that Linda is the sole person in control of this conflicted world: it shows her training with a punching bag to the theme score on the snow-covered rooftop of a tall Budapest building, wearing a red satin karate suit against the white background. Following her workout routine for a while, the camera slowly backs away until she becomes invisible among the large buildings, and the lengthy aerial shot casts a last, 360-degree birds-eye-view, look at the city centre’s landmarks; uniting old and new in one take. (Figures 9-12)

Conclusion

This article examined the detective heroine’s portrayal in the 1980s Hungarian police procedural Linda. As an enduring media hallmark of the region’s transitional cultural processes, the series’ most talked-about feature is its centralisation of a female martial arts hero whose superwomanhood domesticates Western influences. In examining key aspects of this domestication, such as genre mixing, intertextuality, the corporeality of a ‘new’ femininity, and configurations of policing and crime in relation to space and the touristic gaze, I argued that Linda’s cultural work cannot be chalked up to transplanting Western tropes into the local context, thereby creating a putatively culturally incongruous, novel fantasy figure. Equally, her emergence cannot be explained with theories of the female-centred noir/crime genre’s exportable transnationalism and transcultural recognisability either. (Zsámba 2014; Klinger 2018) Through the concept of what, following Garland-Thomson, I term ‘productive misfitting’, I showed that on closer inspection Linda is very much of its time and place, even though the gender-bent twist of a Taekwon-Do fighting ‘detective girl’ seems incongruous with her local environment.

Linda is of course a highly suitable candidate for such transcultural and transnational analysis, given the culturally-geopolitically-ideologically complex backdrop of its origins, and I have shown how the programme signifies the conflicted projects of Western aspirationalism and nationalist protectionism characterising Hungarian discourses at the time of the series’ production. But I also argue that such considerations should always be applied in making sense of the transnationally viable female detective figure, and of transnational media generally. All too often, such discourses limit themselves to arguing the ‘lingua franca’ or ‘exportable’ capacities of Western media, in this process inadvertently reproducing the (otherwise condemned) phenomenon of Anglo-American cultural imperialism. This limiting also underlies recent feminist literature on a reverse-directed television export, the female-helmed Nordic Noir’s transnational malleability and transplantation into Anglo-American and Western European contexts. Recurringly framing Nordic Noir as a cultural influence from ‘peripheral’ nations on the centre (itself an Anglo-and Eurocentric take), these discourses neglect to consider the ‘national’ in such transnational cultural currents. Although Linda is a blatant example of a programme expressing a national (cultural, ideological) identity in its transnational, regional, intertextual meaning-making around gender, what we can learn from it for discussions of transnational exports/imports is the always-present influence of specific national and regional discourses; an element which Anglo-American scholarship tends to sidestep as informing media texts. Such considerations are all the more urgent in an era when Western media cultures and academic discourses recurringly camouflage Euro- and Anglocentrism through commitments to a putatively progressive, yet Western-centric, rhetoric of blanket postcolonialism, multiculturalism and feminism. Such performative progressivism merely expands the centre and reproduces the dynamics it critiques by approaching places, ideas and texts as if they only exist in relation to and as a response to a Western benchmark.

Acknowledgements

All photo credits: MTVA Archívum.

The author would like to thank to Gábor Gergely and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on previous drafts of the piece.

Notes

[1] I use the term episodic television to refer to the established nomenclature of scripted television’s narrational traditions, which differentiates between episodic versus serialised storytelling. E.g. for Jane Feuer, episodic television is characterised by storylines in which the narrative enigma is resolved within the same episode while ‘the underlying social problem … [is] retained as an ‘absent cause’ for the ensuing series’ (1986: 107)—a formulation particularly apt for Linda’s storytelling as will be shown.

[2] Project website: https://www.detect-project.eu/detect2021/ (last accessed 10 May 2021).

[3] In this, I follow Sabina Mihelj’s (2014) call to overcome a binary between methodological nationalism and transnationalism in the study of television. The former, Mihelj argues, often leads to national exceptionalism (an approach typical of socialist media studies, ‘restrict[ing] the possibilities for theoretical innovation that will be relevant beyond our little field’ (2014: 14)), while the latter ‘focuses almost exclusively on exchanges with the West, which has the unfortunate side-effect of reproducing the west-centric bias of existing work on television’. (Mihelj 2014: 15)

[4] Additionally, the Carrie reference was likely less recognizable for a Hungarian viewer than the Alien one, given the former film’s relative obscurity in 1980s Hungary.

[5] For shifting discourses of paternity in the 1980s-1990s Hungarian films as allegories for the regime’s crumbling authoritarianism, see Orban (2017).

REFERENCES

Anon (2020), ‘Pécsi Ildikó: A magyar Gina Lollobrigida fordulatos élete,’ Újságmúzeum, 27 October, https://ujsagmuzeum.hu/pecsi-ildiko-a-magyar-gina-lollobrigida-fordulatos-elete/ (last accessed 27 November 2020).

Bardan, Alice & Aniko Imre (2011), ‘Vampire Branding: Romania’s Dark Destinations’, in Kaneva, Nadia (ed.), Branding Post-Communist Nations : Marketizing National Identities in the New Europe, London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 168-192.

Broughton, Lee (2016), The Euro-Western: Reframing Gender, Race and the ‘Other’ in Film, London & New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Coulthard, Lisa et al. (2018), ‘Broken Bodies/Inquiring Minds: Women in Contemporary Transnational TV Crime Drama’, Television & New Media, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 507-514.

Creed, Barbara (1993), The Monstrous-feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, London & New York: Routledge.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie (2011), ‘Misfits: A Feminist Materialist Disability Concept,’ Hypatia, Vol 26, No. 3, pp. 591-609.

Gergely, Gabor (2016), ‘Women Directors in Hungarian Cinema 1931-44,’ Studies in Eastern European Cinema, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 258-273.

Havas, Julia (Forthcoming), ‘Dream on Princess’: Cultural Value, Gender Politics, and the Hungarian Film Canon through the Documentary Pretty Girls,’ in Gergely, Gabor & Susan Hayward. (eds), The Routledge Companion to European Cinemas, London: Routledge.

Havas, Julia (Forthcoming 2022), Woman Up: Invoking Feminism in Quality Television, Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Havens, Timothy, Aniko Imre & Katlin Lustyik (2012), ‘Introduction’, in Popular Television in Eastern Europe During and Since Socialism, New York & London: Routledge, pp. 1-9.

Heger, Christian (2009), Die rechte und die linke Hand der Parodie: Bud Spencer, Terence Hill und ihre Filme, Marburg: Schüren.

Imre, Aniko (2016), TV Socialism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Imre, Aniko (2020), ‘The Other Kind of Cold War TV (Not So Different After All),’ in Shimpach, Shawn. (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Global Television, New York: Routledge, pp. 385-400.

Kiricsi, Zoltan (2007) ‘Karatefilm a szocializmusban,’ Comment:com, 21 February, http://comment.blog.hu/2007/02/21/title_2800 (last accessed 22 November 2020).

Klinger, Barbara (2018), ‘Gateway Bodies: Serial Form, Genre, and White Femininity in Imported Crime TV’, Television & New Media, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 515-534.

Linda Remixed (2015), Budabeats, https://budabeats.bandcamp.com/album/linda-remixed (last accessed 22 November 2020).

McHugh, Kathleen (2015), ‘Giving Credit to Paratexts and Parafeminism in Top of the Lake and Orange Is the New Black’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 17-25.

Mihelj, Sabina (2012), ‘Television Entertainment in Socialist Eastern Europe: Between Cold War Politics and Global Developments,’ in Havens, Timothy, Aniko Imre & Katalin Lustyik, K. (eds), Popular Television in Eastern Europe During and Since Socialism, New York & London: Routledge, pp. 13-29.

Mihelj, Sabina (2014), ‘Understanding Socialist Television: Concepts, Objects, Methods’, VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, Vol. 3, No. 5, pp. 7-16.

Orban, Clara (2017), ‘When Walls Fall: Families in Hungarian Films of the New Europe,’ in Ostrowska, Dorota, Francesco Pitassio & Zsuzsanna Varga (eds.), Popular Cinemas in East Central Europe: Film Cultures and Histories, London & New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 248-260.

Pavlova, Yoana (2016), ‘Just for Kicks: How a Kung-fu Fighting Female TV Detective Reshaped Gender Norms in the Eastern Bloc’, The Calvert Journal, 30 August, https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/6656/linda-detective-karate-tv-series-hungarian (last accessed 20 November 2020).

Shimpach, Shawn (ed.) (2020), The Routledge Companion to Global Television, New York: Routledge.

Tasker, Yvonne (2002), The Silence of the Lambs, London: British Film Institute.

Thompson, Marie (2013) ‘Three Screams,’ in Thompson, Marie & Ian Biddle (eds), Sound, Music, Affect: Theorizing Sonic Experience, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 147-162.

Toft Hansen, Kim, Steven Peacock & Sue Turnbull (eds) (2018), European Television Crime Drama and Beyond, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Turnbull, Susan & Marion McCutcheon (2020), ‘Outback Noir and Megashifts in the Global TV Crime Landscape,’ in Shawn Shimpach, S. (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Global Television, New York: Routledge, pp. 190-202.

Zsámba, Renáta (2014), ‘Transforming the American Hard-Boiled Hero: Linda, the Tough Female Sleuth in Socialist Hungary,’ Eger Journal of American Studies, No. 14, pp. 127-138.

Film & TV

Alien (1979), directed by Ridley Scott.

Batman (1966-68), created by Lorenzo Semple Jr. and William Dozier (3 seasons).

Cagney & Lacey (1981-88), created by Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday (7 seasons).

Carrie (1976), directed by Brian De Palma.

Charlie’s Angels (1976-81), created by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts (5 seasons).

Kékfény (1964-), Magyar Televízió.

Linda (1984-89), created by György Gát (3 seasons).

Police Woman (1974-78), created by Robert L Collins (4 seasons).

The Silence of the Lambs (1991), directed by Jonathan Demme.

Star Wars (1977), directed by George Lucas.

The Bionic Woman (1976-78), created by Kenneth Johnson (3 seasons).

The Streets of San Francisco (1972-77), created by Edward Hume (5 seasons).

Wonder Woman (1975-79), created by William Moulton Marston and Stanley Ralph Ross (3 seasons).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey