Remembering & Regaining Images: Malayali Women’s Engagement with Photography

by: Vipula P.C. , June 25, 2022

by: Vipula P.C. , June 25, 2022

I was born in Kerala, a state on the southwestern coast of India, which was officially formed in 1956 by merging three geographical regions (Malabar, Kochin and Travancore) which experienced different political and cultural circumstances under the British colonial period. Even before the official formation of the state of Kerala, these regions underwent many phases of modernisation—reforms of familial and marital laws and laws relating to land, the spread of education, and diverse forms of occupation —and in each phase there occurred serious clashes between tradition and new ideas (Jeffry 1987). Kerala’s history of colonialism, as well as its feudal past, affected cultural formations in the region. It was a society comprised of different caste groups (ranging from Malayala Brahmins at the top and Pulaya, as well as Paraya, castes at the bottom), and caste practices and norms that differentiated them and acted as a code of conduct that regulated day-to-day life. Dress, eating habits, and access to amenities and privileges were determined by this code (Logan 1951, Nambutiripad 1965; Devika 2007).

Though small in size, Kerala has been exposed to many foreign influences via its coastline. While examining the historical moments that shaped the region of Kerala, the period of colonial modernity has been considered as a ‘fancied point of beginnings’ of these changes; a period which has changed the lifestyle practices of the state (Sreekumar 2009). The reform movements that occurred in the region emphasised modern education, codification of customary laws, and fighting against social inequalities and caste atrocities. In the piece that follows, I focus on how photography in Kerala has been incorporated into the formation of the region’s larger culture, and on how it has affected the lives of women. I focus in particular on two photographs of my mother, taken in Kerala in the 1970s at a transitional moment in her life.

Into the World of Visual Images

Soon after its appearance in Europe in 1839, photography made its appearance in India. The arrival of photography in the Indian subcontinent was a colonial enterprise. Amateur photography was introduced to the general population in various urban centres, and through the emerging Indian middle class, even though the earliest clients were Europeans (Pinney 2008; Thomas 1981). Kerala was also not far away from this tide. Being a ‘fashionable’ product of modernity, photographic technology along with other popular print and other forms of visual representational media made its journey through the Malayali [1] homes and interacted with women’s lives.

I remember, as a young girl, cutting and collecting images of favourite film stars, writers, and politicians from newspapers and popular magazines, fragments of the handwriting of family members, and many other things which I felt to be important. Amongst the cuttings and images, I also kept old photographs of family members, along with other materials in the scrapbook. There were only a very few photographs, which were taken mainly for official purposes, including headshots collected from college, library, or official identity cards. Everything went into my scrapbook collection, which was not well-organised, and mostly resembled a huge pile of random paper cuttings which would have been found meaningless by anyone else. During those days, I never bothered about what it meant for others, or what would happen to the collection in the future. But for me, it was a major treasure in my life, and viewing them regularly and adding new pieces to the scrapbooks consumed a major part of my weekends. This habit continued until my graduation days. When hostel life began post-graduation, I no longer paid attention to the scrapbooks, and they were locked inside my study table, untouched for years.

‘Do I Have Photographs!’ My Mother and the Forgotten Photographs

In 2018, while navigating through archival sources for my Ph.D. research, my focus settled on the under-explored family photographic collections of Kerala. As the region witnessed the penetration of cameras into familial spaces in the early years of the 20th century, I realised that exploring family archives could provide a way to understand the place of technology in women’s lives. As expected, I faced several practical difficulties in accessing personal collections. I decided to use every possible contact—from social media networks to immediate as well as distant personal connections.

Throughout the initial phases of my fieldwork, I worked from my family home. As days passed, the difficulties I had to face in getting positive responses from individuals and the practicalities of accessing photographs started to give me anxieties over my proposed work. It gradually began to affect my mother, who always stood with me in every stage of my academic life, sensing my passion for higher studies and the severities of criticisms I had to face from society during my PhD. I had never shared anything about my work with her. One day, in an attempt to relieve some of my stress, I mentioned my anxiety over my Ph.D. and tried to explain to her what kind of data I was planning to analyse, and how it had proven hard to access.

My mother Sarojini, who is in her late 60s, is a retired government schoolteacher who currently leads a life immersed in her motherly and grandmotherly duties. She was born to a lower caste Paraya family of central Kerala. Both her parents, Kunjukuttan and Ammu, were illiterate, daily wage earners, and yet they managed to ensure formal education for their three daughters, despite the criticisms and financial difficulties they had to face.

Hearing my anxieties over data collection, my mother decided to intervene. She started contacting her classmates from school and college, as well as her colleagues from her time spent teaching. She also suggested approaching my aunt, her elder sister Thanka, and asking her to check with families with whom their parents used to work as ‘purampanikkar’—people who work outside the household premises. People from lower caste communities used to work for the landlord or ‘janmi,’ but were prohibited from entering their houses. Therefore, they were appointed as non-domestic workers. My mother’s family have always maintained good relationships with these families in spite of caste hierarchies, especially because of their courage in educating their three daughters. My mother recollected the photographs displayed in the ‘verandas’ of those huge houses, and she decided to take a chance at refreshing her childhood friendships. To my surprise, I could see not just the care she showed towards her daughter’s dreams and ambitions, but her own ambitions as a seeker of knowledge. My mother and aunt sat together and started discussing possible families who might have photographic collections for my research. My discussions with them gave me access to people and archives that were previously unknown to me.

As days went by, a passing memory of my mother’s old photographs struck me, but I could not find them anywhere in the house. When I approached my mother to ask about their whereabouts, she could not remember where they were. However, my research interest in old photographs reminded her that she did have a few photographs to suggest, one or two photographs of herself, and others of her sisters. Both photographs of her sisters were kept hanging on the walls in wooden frames. Although she brought the photographs of herself to her marital home, they were never displayed nor were they shown to anybody other than her family members.

Although she cherishes her memories, and had recently shown interest in getting a smartphone to share photographs and to be connected with her peers, she did not show any interest in searching for the missing images of her earlier life. She was certain that they must be ‘irretrievably’ lost amidst the series of other important things in life. She insisted that I consider other photographs, including portraits of her sisters, but I was curious about the images of my mother, which showed that a lower caste woman had gained access to a novel technology, which was a costly venture in those days. I could clearly remember the two wooden framed studio portraits of my mother, and how, as a child, I used to feel jealous of her because she reminded me of an actress who appeared in the regional cinema.

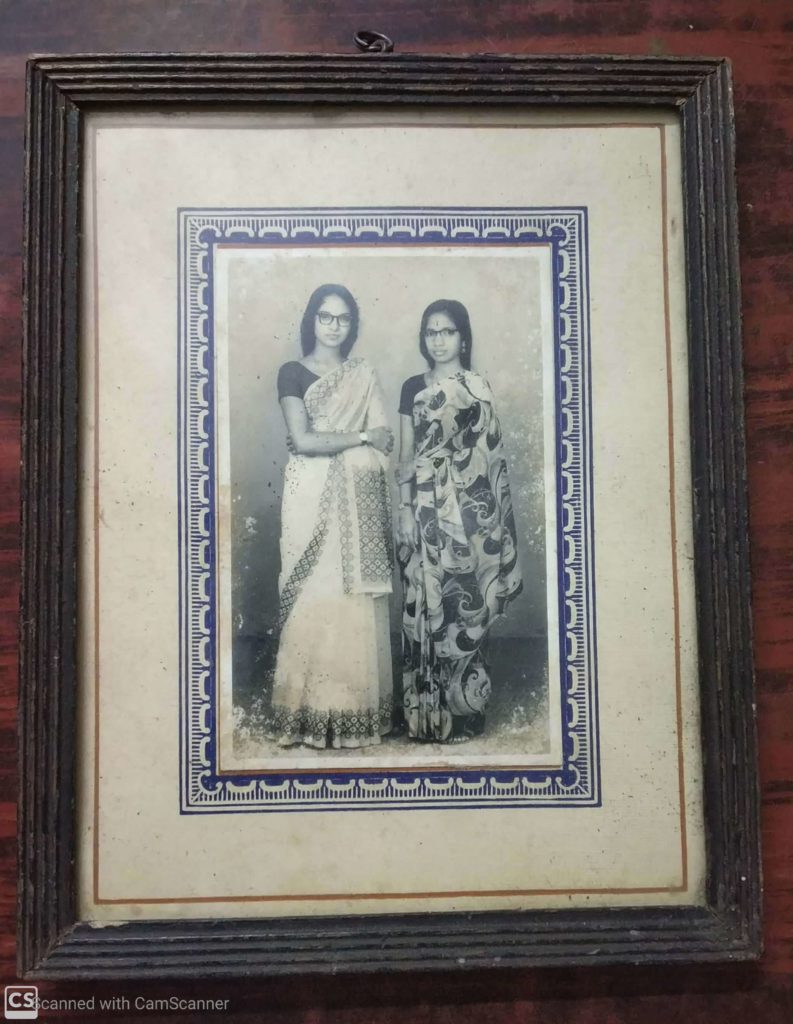

After a month’s search, I found the images of my mother amongst my old scrapbook collections, which had remained ignored —yet safely locked away—for years. There were two photographs, and due to the carelessness with which they were abandoned, the glass frames were on the verge of breaking. One of the portraits showed my mother with her classmate from her Bachelor of Education (B.Ed) course, and the other was taken with my father Chandran, soon after their marriage. Both were studio photographs. Even though there were only two images, I was curious about the stories behind them.

My mother sat next to me while I took one of the photographs to remove the broken glass from the frame. It was a gelatine print of her with her husband, mounted on a thick off-white cardboard sheet, with a yellow border surrounding the photograph. As a result of its sustained contact with the air, the image had started to fade. The other image, taken with her friend, remained intact.

I tried to have a conversation with my mother about the photographs, but she shared only a short description with minimal words. The photographs were taken a year apart. When she got married and moved to my father’s place, she carried them with her instead of keeping them at her parents’ house. She stopped speaking after mentioning the context in which they were taken, as if she had nothing more to say about them. Throughout our conversation, she kept silent or distant from the photographs, which confused me, and instead of talking about the photographs of herself, she spoke about those of her sisters. I could not decode her ‘disinterest’ in what I perceived as a valuable memory of her life.

But at a later moment, she took up the photograph that shows her with her friend Chandramathy, and looking at the photograph she said, ‘See, it is still not that damaged, even if it is old.’ After a year’s break on completing her bachelor’s degree at the Little Flower Convent, my mother had joined the B.Ed. course at Thrissur in 1973. Even though she had initially wanted to be a medical practitioner, she chose to be a teacher after considering the financial, as well as social, insecurities of her parents. It was a respectable profession for a woman aspiring to be a part of what was then considered ‘modern’ and ‘civilised’ life. For her parents, who dreamed of their daughters becoming government jobholders, her decision appealed because it was safe. The educational institution was almost 37 km from her birthplace. By then, her marriage was also fixed with my father, Chandran. He was serving as a clerk in the Food Corporation of India. He lived in a place closer to the institution she joined to study, and my father and his family found it risky for a woman whose marriage had been fixed to travel so far every day, and for that reason she had to stay at a hostel for the duration of her course. ‘His family knew the place better than us,’ my mother said.

Sarojini and Chandramathy were close friends during this period. Chandramathy is from the Malabar region of Kerala, which is almost 200km away from where she and my mother studied. Chandramathy stayed with her maternal uncle, who was an officer at the police training academy near their institution. Even though she did not stay at the hostel, the friends were always together. At the end of their course, the women decided to go to a photography studio to have their portrait taken together as a sign of their friendship.

In the photograph, both are wearing saree with a short-sleeved blouse, which was fashionable among the women then. By the mid-20th century, saree had become a fashion among college-going as well as married women. As I have mentioned above, for Sarojini, her very appearance in the photograph has many meanings and evokes overwhelming emotions. It was not her first experience of being photographed—during the end of her matriculation, as well as in her college days, taking group photographs was the norm. But she never had the economic privilege to pay for and keep a copy for herself. The photograph of her with her friend, dressed in her saree, was the first time she had the financial means to purchase a copy.

In those days, having a saree of one’s own was prestigious and a privilege. After her graduation, Sarojini had to take a break and taught in a regional tutorial college, before enrolling for her B.Ed. The college where she finished her BA insisted that students wear either saree or half saree, which she found unaffordable. Hence, she had to manage with a used saree given to her by the well-off family for whom her parents worked. Since it was compulsory to wear it only once a week, it did not become damaged, and she could reuse it for the whole year.

Being a woman whose marriage was fixed, and who had moved to a more urbanised setting, she had to put more care into her appearance. With the money she saved from the previous year’s earnings, she managed to buy her own saree. When she started to wear a saree, she remembered that none of her female ancestors had worn them before, because they belonged to the lower caste community and were systemically prohibited from wearing clothing reserved for the upper caste, and that she and her sisters were the first to do so. It made her proud and she felt responsible for what she had to attain in her life with the educational opportunities she had, both a symbol of what she had achieved and what she had to prove.

Conclusion

Strategies to shape modern Keralan society have focused on efforts to end caste and gender inequalities. Socio-political, as well as religious, reformist actions were deliberately keen on ensuring the distribution of resources among the public, with an agenda of building a ‘modern’ society based on secular values. Reforms were made to improve the status of women in terms of increasing education, health care facilities, and access to modern-day technologies. This was done with the agenda of improving their abilities in handling spaces of modern domesticity, and modern family relationships (Devika 2007 & Pinney 1987). For systemically oppressed class groups, these efforts offered nothing but a choice to grab the very first offer to have higher education and a ‘modern family’ relationship. Historically, Parayas, as a lower caste group community, were systemically kept away from access to better living conditions and resources. They stood on the lowest strata of the social-cultural and economic ladder.

My mother’s experience is an example of the opportunities and life choices that modernity offered a lower caste Malayali woman of that period. Born into the Paraya community, she had to prioritise her struggles to ensure the utilisation of opportunities that offered mobility in social status. Photography is among such luxuries that she tries to enjoy and possess among her other struggles of life. Besides being a ritualistic activity or norm of middle-class life, the camera can be an ‘extension of genius in the hands of any one of us’ (Sandbye 2014). It is not a surprising that the photograph of my mother and her friend was taken—it was a common practice among the educated youth—but for my mother the photograph holds great symbolic weight. Everything mattered in that photograph, and it is connected to her past as well as her concerns for the future.

To use her words, ‘the only thought we had while deciding to take the photograph was to have something to keep as a memory, but it was beyond that.’ For her, this photograph reminds her of the anxieties she had while completing the B.Ed. Her course was coming to an end. She was about to be separated from a friend who was her sole support during her stay away from home. After finishing the course, what awaited her next was her marriage. From her experience of staying at the hostel itself, she realised the presence of a new relationship that had already started deciding things for her. She knew that her chances of meeting her friend again in the future depended on decisions made by other people.

Acknowledging the role of photography in the period’s larger project of disciplining subjects, it is also worth inquiring about the possibilities it opened. In examining my family archive, we can find the seeds of rebellion against the hegemony of the ‘new patriarchy’ by women (Sarkar 1992). The experience of taking the portrait with her friend before her marriage, and her decision to keep it with her after moving to a different place and beginning her new life, formed a valuable, if largely buried, part of her life. Here the photographs stand not just for the material imprint of a momentary act imprinted on a piece of paper, but rather for the adventure of visiting a photographic studio space undertaken by two women in their twenties, without a male companion, and acknowledges them as modern, educated, and independent.

While prioritising her life choices, what my mother Sarojini had to give up was her freedom, or control over certain choices. The photograph of her with her friend is a reminder of the struggle for women’s spaces and the accessibility of leisure and luxuries. It is also clear that preserving the memory of her own life experience is a luxury for a woman like my mother, who was married to another first-generation learned man from the community, and with whom she shared the collective responsibility of improving their social status and material circumstances.

Attempts to preserve memories in material form by women can be regarded as a mode of resistance, without being submissive to an oppressive structure. In the case of my mother Sarojini, her old photographs, especially that of herself and her friend, stand as a reminder of the spaces she had given up while becoming a modern family woman. Her memories of her adventures as a young college-going girl remind her what she is capable of, as much as her discussions with me in which she reminisced about the past serve as reminders of her struggle to conform and to deal with the pressures of life.

Notes:

[1] Malayalam is a Dravidian language spoken in the Indian state of Kerala. The Malayali people are those who belong to the ethnolinguistic group originating from the state of Kerala.

REFERENCES

Devika, Jayakumari (2007), En-Gendering Individuals: The Language of Reforming in Twentieth Century Keralam, New Delhi: Orient Longman Private Limited.

Jeffrey, Robin (1987), ‘Governments and Cultures: How Women Made Kerala Literate’, Pacific Affairs, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 447-472.

Logan, William (1951), Malabar Manual, Madras: Government Press.

Nambutiripad, Sankaran N Kanipayyur (1965), Ente Smaranakal (My Memoirs), Vols. I, II and III, Kunnamkulam: Panchangam Press.

Pinney, Christopher (2008), The Coming of Photography in India, London: British Library.

Sandbye, Mette (2014) ‘Looking at the Family Photo Album: A Resumed Theoretical Discussion of Why and How’, Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Vol. 6, No. 1, 25419, DOI: 10.3402/jac.v6.25419

Sarkar, Tanika (1992) ‘The Hindu Wife and the Hindu Nation: Domesticity and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Bengal’, Studies in History, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 213-235.

Sreekumar, Sharmila (2009), Scripting Lives: Narratives of Dominant Women in Kerala, New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Private Limited.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey