Queering Suffrage: Embroidering the Lesbian Life of Vera Holme

by: Sarah-Joy Ford , December 13, 2021

by: Sarah-Joy Ford , December 13, 2021

Introduction

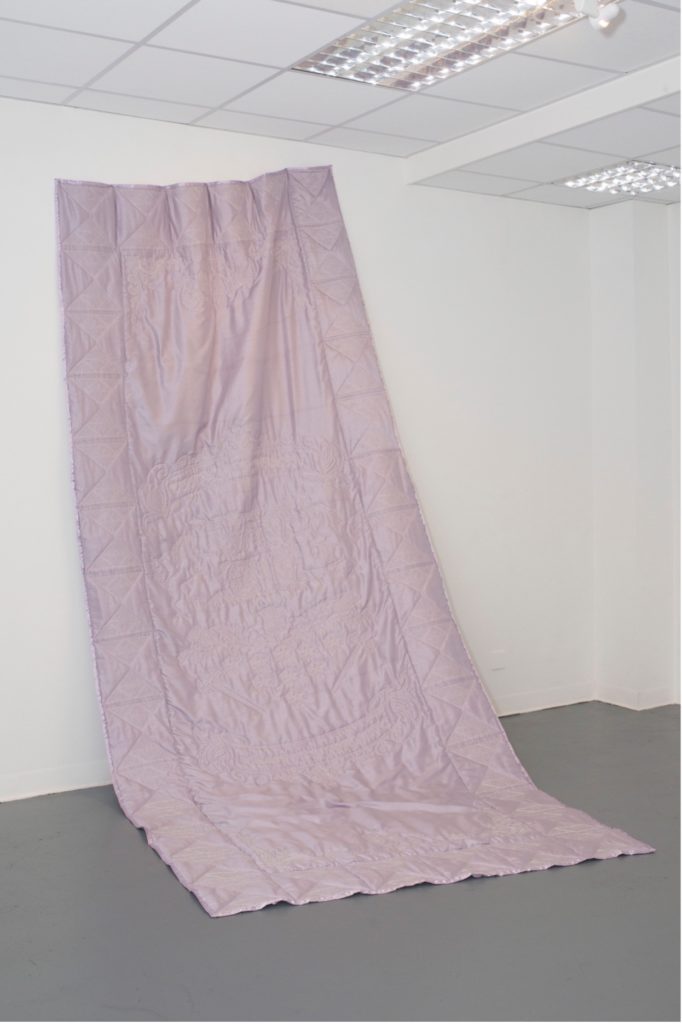

This practice-based paper reflects on the process of making and exhibiting a quilted artwork: V is for Vera who is Keen on the Fun (henceforth the VH Quilt). The quilt and its embroidered motifs re-cite and re-imagine images, anecdotes and symbols from the Papers of Vera (Jack) Holme held at The Women’s Library Archives at The London School of Economics. It was created through a process of patchworking together the imagery and iconography of the suffrage movement alongside the symbols and signifiers of lesbian existence, culture and intimacy. The quilt is an intervention into heteronormative commemorative narratives, and a tender attempt at giving voice to lesbian desire, intimacy and memory in the archive.

The quilt was created as part of the Hard Craft project and exhibition at Vane Gallery in Newcastle, 2018. The collaborative project more broadly explored the significance of politicised craft practices to the suffrage movement, including the making of banners, handkerchief petitions, ceramic tableware, and other ‘disobedient objects’. (Flood & Grindon 2014) This paper situates the quilted strategy within the context of this exhibition, and the lineage of feminist textile art and scholarship that establishes the rich relationship between feminist activism and craft.

The exhibition was organised in response to the 100-year anniversary of The Representation of the People Act, which granted all men and some women in the UK access to the vote for the first time. This anniversary opened up funding and opportunities for cultural events celebrating women’s political histories, as well as handful of newly published books. Although this re-invigorated interest resulted in some exciting projects, interventions, and publications, there was a lack of sustained work undertaken to challenge the collective memory of the suffrage movement as universally white, upper class and heteronormative. (Andersson 2018; Braidwood 2018) Even though relationships, intimacy and love between women clearly threaded through and bolstered the suffrage movement, lesbian histories have been argued over, glossed over, and their life-altering intimacies pushed aside as an irrelevance to the canonical narrative of women’s activism in the UK. What goes on in beds and under quilts has been deemed irrelevant in the politics of public remembrance.

As a lesbian artist making work during the 100-year anniversary of partial women’s suffrage, with a practice dedicated to the work of uncovering and re-visioning lesbian archive materials, making this work felt like an essential intervention into heteronormative narratives of the suffrage movement. The quilt offered me a tender creative method for intervening into the fractured historiographies of the suffrage movement, and the continuing dismissal of the importance of queer women’s relationships and alliances. Informed by lineages of lesbian history and critical theory that negotiate the complexities of lesbian representation, ghosting, and abundance, this quilt takes up the archive of Vera (Jack) Holme in order to shift a small fragment of these hidden intimacies and histories into focus within wider narratives of suffrage history. (Castle, 1993; Jargose, 2002; Traub, 2010) This stitched reconstruction by no means uncovers the full richness of Vera Holmes’s life or lesbian contributions to the suffrage movement, but hopes to open up a space to come into contact with the secrets and silences of the under-explored archive. It is a call for more conversation, more scholarship, and more culture that recognises and represents the importance of queer women’s labours and loves in suffrage history.

The quilt is an intimate object: it protects and warms, covers and comforts. It is the beholder to our most private moments and innermost intimacies. At a centenary celebrating public protest, the lens of quilting relocates the discourse of suffrage memory toward the domestic realm, centring the private friendships, intimacy and love between women that mobilised a movement toward equality.

The Centenary: Politics of Remembrance

The VH quilt and the Hard Craft exhibition were a contribution to the centenary celebrations for the 100-year anniversary of partial women’s suffrage in Britain. [1] Throughout 2018, awareness and interest in women’s history was raised through television, radio and new books including Dianne Atkinson’s Rise Up Women, Helen Pankhurst’s Deeds not Words, Lucy Fisher’s biography of Emily Wilding Davison, the BBC series Suffragettes with Lucy Worsley and plenty of Women’s Hour specials. These have run alongside public programs including: The National Trust’s year of Women and Power; the National Portrait Gallery touring exhibition Faces of Change: Votes for Women; the Museum of London exhibition Votes for Women; A Woman’s Place at Abbey House Museum in Leeds, and Represent! Voices 100 Years On, curated by Helen Antrobus at The People’s History Museum. Cities across the UK erected commemorative statues, including one of Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester by the artist Hazel Reeves, a statue of Annie Kenney created by Denise Dutton in Oldham, and a statue of Alice Hawkins raised in Leicester. Hard Craft was one of many grassroots, community, and artist-led activities that also contributed to the discourses of commemoration.

The centenary specifically celebrates the Representation of the People’s Act 1918, which extended the vote to women after years of hard campaigning. However, this was only limited to women over 30 who met certain economic criteria, and full suffrage for women was not attained until 1928. In this year of celebrating the partial enfranchisement of women, it is important to acknowledge the partial nature of the dominant narratives of commemoration, which often excluded the more marginalised narratives of queer, working class, and women of colour.

The VH Quilt is responsive to the calls from the LGBTQ community for an appraisal and recognition of queer and lesbian suffragettes and suffragists. Ella Braidwood argued in her Vice article that the centenary events showed ‘that the archetypal suffragette has been burned into our collective memory as a certain type of woman, as exemplified by the 2015 film Suffragette: straight, white and able-bodied’. (Braidwood 2018) In her article she highlights The Queer, Disabled, and Women of Colour Suffragettes that History Forgot, interviewing Dianne Atkinson about the Queer Suffragettes featured in her book, including the ‘very open couple’ Lettice Floyd and Annie Williams, who ‘weren’t hiding in any closet; they were out in doing it’. (Atkinson in Braidwood 2018) [2] Pink news published ‘100 Years After Women Were Given the Vote, it is Time to Recognise Queer, Lesbian and Bi Suffragettes,’ quoting MP Angela Eagle:

The prominence of LGBT women in the suffragette movement has often been overlooked, particularly in periods when both society and the law discriminated heavily against LGBT people. But in recent decades rights have been won and attitudes have changed for the better, and we must now proudly celebrate the role that lesbian women played in the suffragette movement. (Eagle in Andersson 2018)

The online lesbian publication Autostraddle posted ‘British Suffrage History: Come for the Democracy and Stay for the Lesbian Drama,’ complete with an L-Word-style map linking women in a network of related pals and gal pals. (Sally 2018) There is clearly a call for a queering of suffrage history, and this kind of history might require some reading between the lines, or between the sheets. This is where the quilt can become an appropriate and evocative tool for shifting lesbian lives out of the institutional archive, and back to the intimacy of the bed.

Hard Craft Exhibition

Women, like craft, are often portrayed as pleasant and placid. This exhibition celebrates protest and outrage, stitched into fabric and fired in the kiln. The suffragettes created a visual language of resistance through posters, pamphlets, banners, sashes, handkerchief-petitions and ceramic tableware.

Many seemingly domestic objects became weapons of dissent and symbols for a societal revolution. On the 100-year anniversary of partial women’s suffrage in the UK, this exhibition of collaborative work draws upon the material histories of dis-obedient craft. (Ford 2018)

This was an exciting year to be a textile artist, as there was a renewed interest in the hand-crafted banners of the suffrage movement in projects such as the 100 Banners organised by Digital Drama and Processions, and commissioned by Artichoke as part of the 14-18 NOW WW1 Centenary art commissions. Working as one of Artichoke’s commissioned artists was a highlight. I was able to collaborate with the LGBT Foundation Manchester, and Republica Internationale women’s football team based in Leeds to create a banner protesting the ongoing homophobia facing women in sport. I was also invited to create banners with Loughborough Students’ Union, and with the young women attending Pavilion’s Rebel Girls summer school program. The Hard Craft exhibition too, included a series of bright banners that reworked and reclaimed archival anti-suffrage postcards depicting suffragettes as cats mewling for the vote.

The Hard Craft exhibition was part of an Arts Council Funded project developed by myself and Juliet Fleming, which took place at Vane Gallery in Newcastle. The project was informed by research at The People’s History Museum (Salford), The Pankhurst Centre (Manchester), The Women’s Library (London School of Economics), and the Palczewski Suffrage postcard archive (University of Northern Iowa). The program included an exhibition, a series of workshops with community groups, an archive screening—There is Power in the Material, showcasing films from the Cinenova archive that ‘explore the politics of domestic spaces and highlight the use of craft mediums within feminist and queer protest movements’—and a talk by Helen Antrobus, entitled Activism on our Sleeves: Radical Women and Dress. (Proctor, in Ford 2018) Spanning three rooms, the exhibition included individual and collaborative works in both textiles and ceramics, as well as a small archive room containing artistic samples, remnants and experiments, alongside information on the archival sources used to inform the work.

Hard Craft: Quilting in the Year of the Banner

At the time of embarking on this project, I had just started my practice-based PhD, which proposes quilt making as an affective strategy for re-visioning lesbian archive material. I initially planned to keep these projects separate, but, as is often the case with art practice, entanglements almost always form between projects. In the light of the calls for more lesbian visibility in the suffrage centenary, I wanted to create new works that broke this sapphic silence. When I came across Anna Kisby’s article detailing the story of Vera Holme’s life from the archival collection at LSE, I knew that this story would provide the ‘material’ for my quilt.

Lesbians have been present mostly as an absence, as an ‘amor impossibilia’ in the centenary year. (Castle 1993) Crafted by lesbian hands, and informed by lesbian sensibilities the VH Quilt, and this subsequent article, shift the lesbian into focus. Situated within an exhibition of banners, pikes and jumpers—all symbols of public marches and parades—this article focuses in on the quietness of the lilac work quilt. The embroidered motifs patchwork together fragments of a lesbian life, stitched in pale thread. Sinking into the fabric, they shift in and out of focus in material synchronicity with the historical obscurity of lesbian lives. Quilts are blankets made up of three sandwich layers to create warmth. They are domestic objects, made for the home and the bed. The use of the quilt shifts suffrage dialogue out of the streets and toward the often invisible intimacies of domestic space.

Central to the quilt are the elaborately embroidered initials EH and VH; all the other designs extend around this central motif. This sapphic monographing directly references the bed that Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield (her partner) shared. After Evelina’s death in 1920, Vera wrote a list of belongings she wanted to be returned from their shared home. On that list was ‘1 Bed with carved sides V.H. and E.H.’ and below ‘1 set of Carving tools’ (Personal Papers 7VJH/4) suggesting not only that their bed was inscribed with their initials, but also that this may well have been done by hand by the women themselves. This cannot be anything other than an act of love, devotion and commemoration, within which these women chose to locate the bed as a site of shared importance to them. Made for the bed, quilts bring warmth and comfort as well as beauty. The quilt is soft, it absorbs—sweat and fluids holding memories like stains. (Sorkin 2012) A quilt can keep stories. This quilt re-tells the story of this romantic gesture. In a year of politics and publics, the quilt returns to the most intimate space of the shared bed.

Suffrage and Disobedient Craft

The use of the quilt—and more broadly, textile crafts as a feminist methodology in this exhibition—is part of a lineage of marginalised and rebellious histories of women’s craft and textiles. The suffrage movement mobilised women’s domestic needle work skills in order to create a visual language of resistance through handmade banners, sashes, handkerchief petitions, and ceramic tableware. These performative objects were steeped in sagacious symbolism, often referencing historical figures such as Joan of Arc, Boudica, and Jane Austen within the suffrage colour scheme of white, green and purple.

After the industrial revolution and the decline of cottage industries, sewing, embroidery and other textile crafts became increasingly associated with feminised domestic labour (Bratich & Brush 2011) These notions contributed to a ‘complex network of power relations’ that excluded women’s crafts from discourses of high art and economic circulation. (Aurther 2012: 210) Craft became a conceptual limit: reducing women’s needlecraft to docile objects, with little meaning beyond function—they were to be produced, consumed and displayed in the home, rather than in the public space of the street or the gallery. (Adamson 2007; Aurther 2012; Jefferies 2020) Embroidery became increasingly associated with notions of the ‘fixed and un-changing, eternally feminine,’ an appropriate activity for the docile and domesticated woman, bent quietly over her ‘timeless, mindless’ needlework. (Parker 1984: 191) These assumptions and restrictions were challenged by the suffrage movement—they brought women’s domestic skills out of the home and into the streets, disrupting the strictly gendered binary division between private and public space.

Banners were particularly important, primarily produced for the WSPU by The Artist Suffrage League using embroidery and appliqué techniques usually reserved for domestic production, repair, or ecclesiastical purposes. (Tickner 1988) Drawing too on the material histories of painted trade union banners (mostly produced on mass by Tutils & Co.), needlework was deployed in alliance with paint. (Tickner 1988) These carefully crafted banners demonstrated the dedication of women to the cause of suffrage by deploying the skills that had been dismissed as domiciliary crafts rather than serious or political artwork, as amateur rather than professional. The banners were intended to ‘evoke femininity, but femininity represented as a source of strength, as opposed to as evidence of women’s weakness’. (Parker 1984: 197)

These feminine values were also upheld by suffrage organisations encouraging women to ‘dress in modest yet feminine clothing,’ and for marches, white dresses ‘showed off the elaborate banners to their fullest, but also evoked images of purity and virginity’. (Cohler 2010: 52) The dress codes upheld racial, sexual and middle-class norms of womanhood, emphasising respectability and that suffrage would not result in the abandonment of the feminised domestic sphere, as was depicted in so much anti-suffrage propaganda. (Antrobus talk 2018)

The stitching of the initials VH and EH on the quilt directly gestures toward the powerful ways suffragettes signed their names in stitch as a political act. In prison, ‘women embroidered handkerchiefs with their signatures, bringing together the tradition of political petition and protest with a female social tradition by which guests would embroider their signatures for the hostess to commemorate a visit’. (Parker 1984: 200) These handkerchiefs were sometimes embroidered with violets like the ones that appear on the quilt, below the initials. The act of signing in stitch continues to be a powerful one.

Feminist Artists & Craft

For the suffragettes, embroidery was part of a carefully constructed spectacle of respectability: ‘employed not to transform the place and function of art, but to change ideas about women and femininity’. (Parker 1984: 197) However, it was the feminist artists of the 1960s, 70s and 80s that would make this a dual challenge. Artists including Eva Hesse, Harmony Hammond, Mariana Abaknowitz, Louise Bourgeois, and Annette Messager were part of a re-evaluation and reclamation of textiles as a deeply fraught and political ground for exploring womanhood, bodies, labour, and the boundaries of art itself. These artists mobilised textiles as ‘a vehicle and a conduit for difficult and complex meanings’ by drawing on its material and metaphorical properties: its closeness to the body, its ability to absorb and contain, warm, and protect. (Dolan & Holloway, 2016; Golda, 2016; Jefferies, 2017, p. 54; Sorkin, 2012) By bringing women’s traditional textile crafts into gallery spaces these artists were centralising the importance of ‘unfairly denigrated, domestic female labour,’ and challenging the ‘sexist, racist, and classist’ standards that had excluded them. (Bryan-Wilson 2017: 14)

Feminist artists utilising textiles invoked and critiqued an idealised femininity that has been ‘ideologically shaped by the domestic sphere and its connotations,’ that equated and conflated women’s bodies and the home. (Kokoli 2016: 94) The domestic became an evocative site for critique and intervention. Quite literally so in projects where the house became a portrait of womanhood, including Woman House led by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro as part of the California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Program in 1972, and Portrait of the Artist as a Housewife by Feministo at the Institute of Contemporary Art (London) in 1977. These interventions into the gendered construction of the home contested ‘the naturalisation of women’s domestic work’ and its restriction of women to the home ‘but also to unproductive (reproductive), non-aesthetic (decoratively ‘creative’) sphere of production’ (Kokoli 2016: 106),

My contemporary practice is heavily informed by the feminist artists who drew on the culturally gendered specificity of the quilt as a rich ground for exploring notions of femininity, domestic labour, and women’s marginalised creative work. In the catalogue for The Artist and the Quilt, Lucy Lippard argued that the quilt is a ‘diary of touch, reflecting uniformity and disjunction, the diversity within monotony of women’s routines’ and a ‘feminist resurrection of our foremother’s lives’. (Lippard 1983: 32)

Contemporary Artists, myself included, continue to draw on textiles as a powerful medium for articulating marginalised experiences. Extending and expanding on the notion of femmage, Queer artists have recognised and reclaimed stereotyped and stigmatised craft practices through a process of ‘reclamation, reappropriation, performance and disidentification’ similar to the reconfiguration of the term ‘queer’ from an insult to a ‘place of empowerment’. (Roberts 2012: 247) My work sits alongside, and in succession to, the queer artists invoking textiles as unruly, unstable and excessive mediums in order to articulate queer identities, histories, desires and temporalities. These include Jesse Harrod, Aaron McIntosh, Josh Faught, Alison Mitchell and LJ Roberts. (Chaich & Oldham 2016)

The use of textiles in the Hard Craft exhibition is explicitly located within these histories. The quilt, with its own specificities and complexities: its direct reference to the domestic, to the bed and to the vulnerable body, is a powerful tool for shifting into focus the hidden lives of women, queers and lesbians.

Lesbians & Suffrage History

The historical materials documenting this period are far from lacking, as the suffragettes were prolific autobiographers: Emmeline, Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst, Ethel Smyth and Constance Lytton each chronicled their contributions to the suffrage movement. (Purvis & Wright 2005) The suffragettes also valued the material culture of the movement, keeping papers, banners, badges, buttons, and crockery which were handed down in families or donated to the Museum of the Suffrage Fellowship—which later became the Suffrage Fellowship Collection at the London Museum—which ‘contributed to their own historical survival’. (Bradley 2000; Kean 2005) The importance of long-lasting relationships between women is well documented. Women including Naomi ‘Micky’ Jacob, Lilian Barker, and the pacifist suffragists Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper all had primary relationships with women that fed, supported, and influenced their political lives.

Virginia Woolf (VW) and the suffragette and composer Ethel Smyth had a long-lasting friendship documented in their letters, wherein they shared their experiences of patriarchy, loving women, and creating a career in male dominated spaces; indeed, in the last 12 years of VW’s life, over a quarter of her letters were written to Ethel Smyth. (Wiley 2004) In a letter to Quentin Bell on 3 December 1933 VW wrote: ‘[i]n strict confidence, Ethel [Smyth] used to love Emmeline [Pankhurst]—they shared a bed’. (Wiley 2004: 395) While researching in the VH archive, I noticed several letters from Woolf’s most famous and long-lasting lover Vita Sackville-West, addressed affectionately to ‘My Dear Jacko.’ Discovering this friendship with another well-known lesbian felt like a pleasurable uncovering of the strands and threads of the incredible Autostraddle lesbian-suffragette chart.

However, in the ‘theatre of memory’ suffrage histories, in particular the sapphic suffrage histories, have been sites of tension. (Samuel in Kean 2005: 1) After a flurry of initial male scholarship on women’s suffrage, feminist historians have gone about the work of challenging what June Purvis calls ‘masculinist discourse’ produced by male historians such as Martin Pugh and David Mitchell. Both authors have used strategic infantilisation and the invocation of hysterical spinsterhood in order to subtly diminish the achievement of suffrage. They situate the achievement as despite, rather than as a result of women’s campaigning, reinstating political efficacy to the male politicians. (Pugh 2007) Mitchell went so far as to suggest that on an unconscious level the suffragettes were so sexually frustrated that they actually wanted to be assaulted and raped by policemen. (Mitchell 1977)

In 2000 the Observer published a short article entitled ‘Diary Reveals Lesbian Love Trysts of Suffragette Leaders,’ pre-empting the publishing of Martin Pugh’s book The Pankhursts. The article discusses his assertion that the leaders of the suffrage movement led ‘promiscuous lesbian lifestyles,’ through evidence found in Mary Blathwayt’s diaries, which contain notes about who was sharing a bed. This claimed that ‘tensions felt, both physically and psychologically, meant the activists had to find sustaining relationships within their own ranks,’ and stated that Christabel, as the most attractive of the Pankhursts, was the subject of ‘a rash of crushes across the movement’. (Thorpe & Marsh, 2000)

This characterisation of women’s relationships as an emotional crutch to be used while separated temporarily from men undermines women’s political efforts, painting them as mentally unstable and sexually frustrated, while trivialising women’s relationships with each other. Purvis has been a strong critic of this ‘masculinist approach’ as lacking engagement with autobiographies and personal testimonies, dismissing them as largely fantasist, and presenting the movement as a single issue campaign. (Purvis 2013) Purvis has published her astonishment at Pugh’s claims that Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney had led a ‘promiscuous lesbian lifestyle,’ the dismissal of Christabel as ‘emotionally stunted because of the lack of men in her life,’ and the characterisation of Emmeline’s life as one of ‘mounting personal tragedy’. (Purvis 2013: 583) However, her argument stops short and fails to engage with the deeply problematic use of ‘lesbian’ as an accusation, insult or method of dismissal. These masculinist discourses have used the accusation of lesbianism to undermine women’s political efficacy, and some feminist historians have failed to acknowledge lesbian relationships, or to challenge the homophobic nature of these critiques.

Purvis does, however, celebrate feminist historical progress through a diversifying of scholarship, to include the transnational, international discussions of spectacle and performance alongside literary, media, and drama-based interpretations. The Hard Craft exhibition and the VH quilt aim to extend this feminist reclamation and scholarship to include lesbians and centralise the importance of intimate relationships between women in the movement.

The Problems of Lesbian History

The work of doing lesbian history faces the dual difficulties of sexism and homophobia, excluded from law as an unspeakable filthiness, dismissed or erased from history and even camouflaged by lesbians themselves. (Castle 1993; Love 2007; Wilton 1995) Femininity and homosexuality have historically operated outside of the field of vision. Sitting at this junction, the problem of lesbian history is often a representational one. In the face of historical and archival gaps, silences and the unimaginable, the question always returns: ‘but what do lesbians do?’. (Castle 1993: 30)

In the ground-breaking book Surpassing the Love of Men, Lillian Faderman highlights that lesbianism has primarily been regarded ‘as a sexual act,’ and that historians have been ‘unwilling to give it the dimensions they might attribute to a serious male-female love relationship’. (Faderman 1985: 37) In 1989, the women of the Lesbian History Group asked ‘Does it really matter if they did it?’. (Jeffries 1989) This is indeed a strange burden of proof to bear in the face of so much evidence of passion, dedication, and intimacy between women through the diaries and letters of suffragettes. Is it really necessary that we prove they had sex before claiming them as part of queer history? In her talk at LSE Sapphic Suffragettes: the Role of Lesbians in the Fight for Votes for Women, Hilary McCollum (2017) asked, rather frustratedly: ‘what are we looking for, a smoking dildo?’

The quilt is a refusal of these technologies of dismissal and invisibility. It is a direct re-imagining of the lesbian bed: the site of the unknown and un-imaginable activities between women; a material intervention into absence and silence.

Quilting in the Archive

The VH quilt’s intervention into the lesbian silences of suffrage historiography is pieced together from the wealth of materials held in the Papers of Vera (Jack) Holme, held at The Women’s Library at The London School of Economics. The quilt is digitally embroidered, with images and texts sketched and re-imagined from the archive and elsewhere. I approached the collection holding a thrifty quilter’s patchwork method in mind—I gather fragments from archives, alongside my own memories, imagination, lesbian symbology, culture, and iconography. Often the thrift of piecing is necessary when working with the spaces, silences, and lack of lesbian history as a process of reclamation and re-evaluation of the scraps and gaps left behind. But in this archive, I was faced with abundance rather than scarcity, and a wealth of materials I could never hope to engage with in the little time I had. In pale thread, snippets of her extraordinary life are stitched.

The quilt’s dusky lavender colour is a reference to one of the three suffrage flag colours. It is also a candid wink to the historical association of lavender and homosexuality—as in lavender marriage, lavender scare, and Lavender Menace (a New York lesbian activist group that later became The Lesbian Avengers). The pale stitches sinking into the lavender satin call the viewer closer, to untangle and decipher the embroidered images and texts.

Vera Holme (1881-1969), nicknamed Jack or sometimes Jacko, was the daughter of a timber merchant. When her diaries start in 1903 she is only receiving a small, erratic allowance from her father, and needs to earn a living as an actress, singer, and model. (Murphey 2017) These diaries include references to a relationship with ‘Aggie’ with whom she shares a bed—on one instance being joined by Rosie for ‘great fun’. (Kisby 2014: 124) She toured with theatre companies, a contralto for the D’Oyly Carte chorus at the Savoy (1906-1908), played Hannah Snell in A Pageant of Great Women, and was even a reluctant artist model. (Kisby 2014; Stone 2013) Searching for visual material to inspire me, I was rewarded with some fantastic publicity photographs of Vera Holme wearing the garb of the cross-dressing acts of the Edwardian music hall era.

Measuring 180cm x 400cm, the quilt slouches from the top of the wall, spilling onto the floor of the gallery. It is too big for a bed, not quite a quilt. It does not fit on the wall either, so it is not really a wall hanging. It is theatrical, like the woman it was made for. Protruding into the room it reflects the nature of lesbian history—hard to define, and a little bit difficult, its material indistinctness resonating with the ambiguous position of lesbian histories in research, slipping through marginalities and disciplines.

In 1908 Vera Holme joined the WSPU and also became a member of the Actresses Franchise League, who performed outside Holloway prison to raise the spirits of those incarcerated. Vera herself spent time in Holloway in 1911 after being arrested three times for stone throwing and obstruction. (Campaign for Women’s Suffrage 7VJH/1) In 1906 Vera Holme and Elsie Howey hid overnight inside an organ at the Colston Hall in Bristol. and interrupted a men-only speech given by Augustine Birrell (the Liberal MP for Bristol North), shouting ‘Votes for Women! Give Women their political freedom!’. (Atkinson 2018: 145) The small flowers on the quilt mirror the flower designs used in suffrage pin badges, marking her dedication to the cause of suffrage.

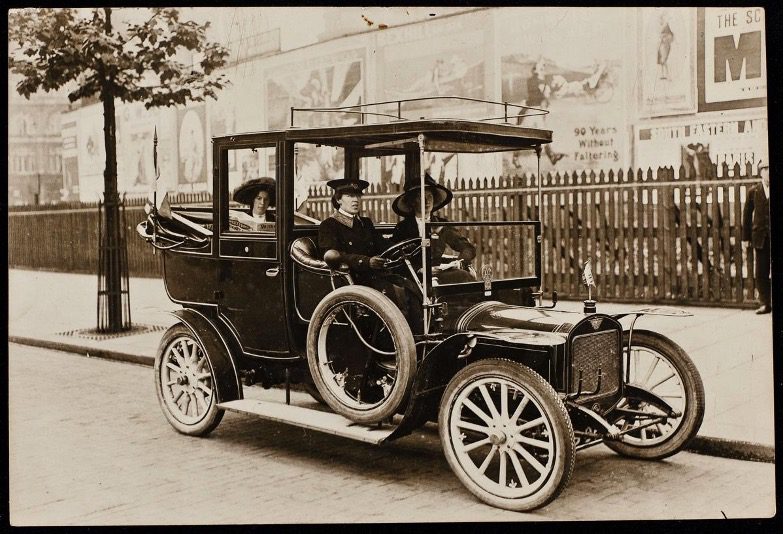

Vera Holme became the first female chauffeur in Britain, as chauffeuse to the Pankhursts. The car that she drove is embroidered on the top of the quilt, clearly a source of pride both for her and for the WSPU, who sold images of her in uniform as postcards to raise funds. At the centre of the quilt, two horses rear up, representing her passion and prowess as a rider, as someone who stewarded marches on horseback, and in 1909 rode ahead of Mrs Pankhurst from the Women’s Parliament to carry a petition to Herbert Asquith. (Atkinson 2018) It was during this period that she began a long-lasting relationship with Evelina Haverfield. Also a member of the WSPU, Evelina established the Women’s Volunteer Reserve; a women’s auxiliary unit that trained women to work in transport to support the war effort, of which Vera became a major in 1914. (Kisby 2014) In 1915 they both joined the Scottish Women’s Hospital unit, and were deployed to Serbia as an ambulance driver and head of the transport unit respectively. (Murphey 2017)

To an excited lesbian in the archive, the image of them photographed together in striking military uniforms sits in a lineage of lesbian culture depicting lesbian war ambulance drivers, including The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall, and The Night Watch by Sarah Waters. It may appear as an outward expression of cultural lesbian identity, but there is no evidence that, at the time, a cross dressing, ambulance driving, trouser wearing suffragette would necessarily be read as lesbian. (Doan & Garrity 2006) [3] The uniformed women ambulance drivers attending the front lines were ‘depicted as combining manly virtues of mechanical competence, driving skills and courage with female qualities of nurture and tenderness’. (Hall 2016: 125)

In 1915 they were held as prisoners of war for four months, after which Vera Holme worked on the front lines in Russia and Romania. A letter from the Joint War Committee documents the return of photographs courtesy of the Austrian Government, highlighting how fortunate it is that these photographs have survived. After some time in Scotland, Vera returned to Bajina, Serbia, as an administrator and aid worker for the Honourable Evelina Haverfield’s Fund for Serbian Children, although here she had relationships with other women, and Evelina reduced the amount of money left to her in her will. (Kisby 2014: 132) It was here that Evelina passed away from pneumonia in 1920, which is painfully recorded in Vera’s diary. Having never viewed archival diaries before, I was unsure where to start—but knowing the date of Evelina’s death, I looked for the 1920 diary. Vera’s diaries are tiny, and her handwriting unbelievably cramped and almost impossible to read for someone not trained in palaeography. The front of the diary is stamped with THE HON, EVELINA HAVERFIELDS FUND FOR SERBIAN CHILDREN. In order to read the fragile thing, I laid it out gently on a paper pillow to rest its old spine. Her pain, its immediacy, is present in the miniature scrawl, recording her temperature each day, washing her hair and staying up with her until 4am recording her delirium and visions, her calls of ‘who will look after my children now?’. (Diaries 7VJH/6) At the end she kept saying Vera’s name. The quilt is embroidered with small crowns taken from the Serbian Flag, representing the place where Vera worked with Evelina and eventually lost her. Vera’s life, and love life, did not end here in Serbia, though. The embroidered Scottish thistles represent the land where she chose to settle, and she lived with Margaret Greenlees and Margaret Kerr until she moved into a nursing home in Glasgow, dying in 1969.

The quilt records too, her joys: depicting hunting dogs and horses that are in so many of the archive’s photographs, reflecting her keenness as a hunter revealed in the poems that she wrote for Evelina. This includes fox hunting, playfully referred to in one of her poems; Alphabet for Evelina Haverfield written on 24th December 1911: H Stands for Hounds.

There are also spaces of silence in the archive, the loudest of which being the lack of letters between Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield. This absence opens up so many questions, about where they are and who might have removed them. It is common for women’s correspondence to be destroyed or hidden, particularly when they document love between women—sometimes, indeed, by the women themselves as an act of camouflage and self-preservation. (Castle 1993) The quilt stitches Vera Holme into contemporary lesbian history and culture, adding in the symbol of the labrys, or double-headed axe, which was not yet in use as a lesbian symbol at the time. This patchworking of temporalities is a wilful reclaiming and reinscribing, a folding into the lesbian imaginary. As an artist I am able to stitch into the silences of the archive and fill them with my re-imaginings. Creative practice allows me to make new assemblages of meaning from the past, taking pleasure in filling up, and stuffing the gaps and spaces in historical records.

The digital quilting is done in a variegated white thread, just visible rather than contrasting with the fabric; this echoes the long tradition of quilted white work (white thread on white fabric). Mennonite white work quilts are said to use white on white, as it symbolises purity, service, submission, and a lack of sinful pride in one’s work. (Epp 2008) The quiet stitches play with notions of silence, invisibility, and pride. Like lesbian history, it is not instantly readable: the viewer must move closer to the quilt in order for the images and text to become legible.

With the scale of the collection and the richness of this carefully documented life, it seems odd that no full biography has ever been written. The best biography remains Anna Kisby’s article, written while she was the archivist at The Women’s Library between 2006 and 2009, during which time she oversaw the acquisition and cataloguing of the Vera Holme archive. (2014) Although she has been mentioned in lesbian and suffrage history books by Dianne Atkinson, Rebecca Jennings, and Emily Hamer, there remains much to be done. As Kisby highlights, the diaries in the collection have never been fully read or transcribed, which would provide a rich ground for future research. Perhaps the letters between Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield could even yet be found.

What do Lesbians Do in Bed?

In a blog post, the socialist-feminist writer-historian Esther Freeman asks: Lesbian History: is it any of our business? Freeman proposes focusing on women’s ‘daily struggles of breaking with heteronormative values’ rather than ‘picking apart the bedroom antics of some of our most important women’. (Freeman n.d.) This kind of reduction of lesbian history to ‘picking apart bedroom antics’ needs to be challenged. The quilt is a material answer to this tedious question. Rather than unpicking, the quilt offers stitching as a strategy for materialising the pleasures, and the political importance of what suffragettes do in bed.

The question what do lesbians do in bed? has always been a political one. In patriarchal phallogocentric logic, lesbianism, and what lesbians do in bed, has been outside of the field of vision, as the unimaginable. In terms of legalisation, lesbian sex has never been directly prohibited in law—instead it has been subject to ‘an incredulousness that would deny the space of possibility’. (Jargose 2002: 3) An amendment to the Criminal Law Act of 1885 was proposed in 1921 to include ‘acts of gross indecency between female persons’—the clause was dropped, as it would ‘do harm by introducing into the minds of perfectly innocent people the most revolting thoughts’. (Oram, Alison & Turnbull 2001: 168) This was the ‘rhetoric of incredulity’ functioning ‘as a mechanism of prohibition’ through omission; lesbianism was constructed as the unspeakable, ‘not only as ontologically impossible, but as epistemologically obscure’. (Traub 2010: 34)

In 1985, Caroline Sheldon offered an answer to this question in her 10-minute film: 16 Rooms or What do Lesbians do in Bed? The film begins with a tongue in cheek graphic of white arrows on a black background pointing toward ‘clinical terminology’ in the centre including ‘tribadism,’ ‘manual manipulation,’ and ‘cunnilingus.’ The film shifts to documenting lesbians reading, knitting, eating, spending time with children, pillow fighting and petting cats in bed. The film plays with expectations, and heterosexist fascinations of the impossible mechanics of lesbian sex outside of the phallogocentrism of the straight mind.

The bed is established as a complex site for intimacy, learning, sustaining and pleasure all at once. In a heterosexist world, making space for lesbian intimacy and politics in the bed is essential. The film was screened as part of the Hard Craft exhibition and the There is Power in the Material screening, organised in collaboration with Cinenova Feminist Film and Video Archive. Situating this film alongside a Suffrage-themed exhibition created a connective attachment between the histories of lesbian suffragettes and the lesbian activism of the 1980s and 1990s, where the bed functioned as a site for female pleasure, power, and activism.

The quilt is another answer to this question, its material form insisting on the importance of the intimate domestic spaces and collective living situations in which women of the suffrage movement loved, collaborated, and fought for equality. It is an invocation of the literal bed belonging to Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield, physically marked by lesbian love as a site of significance. Their act of carving their initials onto the wood of their shared bed is repeated and re-made in stitch. This private act documented in one line, in a list, in an archive, is made monumentally public. We might not know what they did in bed, but it was clearly a site of great shared importance, and it is really not that hard to imagine. The quilt opens up a space for the pleasurable lesbian imaginary, as a materially resonate strategy for stitching into the spaces of silence, incredulity, and the unimaginable.

Figure 7: Sarah-Joy Ford, V is for Vera who is Keen on the Fun (detail), 2018. Photo: Judith Fieldhouse.

What do Suffragettes do in Bed?

The question of what suffragettes did in bed is of central importance to their history, not only in their presence in each other’s beds, but in their absence from the heterosexual marital bed.

Above and below the initials on the quilt are scrolled the words: Votes for Women, Chastity for Men—the term coined by Christabel Pankhurst in The Great Scourge and How to End It, her blazing manifesto on sexually transmitted diseases and women’s rights. In this, she argues that ‘[v]otes for Women will strike at the Great Scourge in many ways’ bringing respect for women both in public life, as well as domestic. (Pankhurst 1913: viii) She silenced the criticisms of suffragettes’ destruction of property with ‘the retort that men have destroyed and are destroying the health and life of women in pursuit of vice’. (Pankhurst 1913: xi) She defended too the right of women, including herself, not to marry. Her voice shifts the suffrage movement away from the single cause narrative of the vote, and politicises the bed as a battleground for women’s rights, proposing the withdrawal of women’s sexual labour as a weapon for emancipation—a tactic that was later used by the political/separatist lesbians in the 1970s and 80s, who advocated lesbianism as a feminist political strategy to withdraw labour and escape from the patriarchy. (Enszer 2016; Group 1981; Lesbians 1970)

Christabel’s refusal of men has been illustrated as irrational, as a frigid spinsterhood. As Purvis and Wright highlight, her lack of male partner is constantly used to illustrate her social and mental deviance in the writings of both David Mitchell and Martin Pugh. (Purvis & Wright 2005) This fear of women acting outside the binds of heterosexuality was pre-empted in George Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935), which describes the masculine militant suffragettes as comprising a movement of ‘pre-war lesbianism’ (Cohler 2010: 34), though he takes pains to desexualise this lesbianism by describing it as ‘more sensitive than sensual’. (Dangerfield 1935: 148) Equally, Anne Lister’s (1791-1840) diaries—published by Helena Whitbread in 1988—were assumed to be a hoax, so unimageable in their ‘jaunty sexual explicitness’. (Castle 1993: 11) Even when lesbianism is acknowledged, lesbian sex remains the unimaginable in suffrage history.

To my knowledge, Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield were not involved in Christabel Pankhurst’s campaign against vice, but I wanted to bring this important and overlooked text into contact with their story. Although Evelina had a husband and children, and Vera had many other lovers (both while Evelina was alive and after her death), they withdrew their labour from the economy of heterosexuality in order to fight for justice and the political freedom of others. Photographed together in their SWH uniforms, the couple represented the ‘twin spectres of culturally masculine and domestically absent voting women’—a fearful figure, often represented in anti-suffrage propaganda to symbolise ‘the deterioration of gender norms and the dissolution of an enclosed domestic sphere’. (Cohler 2010: 40)

Their initials on the quilt are crowned not only with the labrys symbol, but also the blue nautical star, which was used by lesbians in Buffalo, New York in the 1940s and 50s as a wrist tattoo that allowed them to recognise each other. (Lapovsky Kennedy & Davis 1993) This piecing together of timelines and iconographies opens up new and unexpected encounters between the past and future of lesbian lives. As part of this lesbian quilt, Votes for Women Chastity for Men is re-contextualised and queered, and the love between Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield is recontextualised in the bed and within lesbian sexuality and intimacy.

Conclusion

Lesbianism is not, and has not been a separate part of women’s lives but an inalienable part of the fabric of their experiences and their choices. (Hamer 1996: 10)

The relationship between Vera Holme and Evelina Haverfield was clearly important in many ways, and marked Vera for the rest of her life, through her dedication to campaigning for Serbian Aid and Reparations long after Evelina’s death. Similarly, the relationship between suffragist Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth clearly shaped their politics, leading them to create the proto queer private publication Urania in collaboration with Irene Clyde/Thomas Baty in 1915. (Hamer 1996: 67) These relationships between women are so much more than ‘bedroom antics:’ they were loves that were both emotionally profound and profoundly political.

The quilt offers a form for ‘queer rhetorical worldmaking around memory’ as a specifically lesbian memory making tool outside of hegemonic, administratively sanctioned monumentality. (Dunn 2017: 212) The quilt is situated within a lineage of women’s politicised craft practices, and the critical reclamation of domesticity as a site for radical actions, and a tool for dissent.

The quilt, in its reference to the bed, is a direct engagement with—and material intervention into—the fraught debates about what lesbians did in bed. Taking up the fragments of the archive, the quilt is a tender re-making of a small moment in two politically and emotionally entangled lives: the act of carving their initials on the bed. The quilt repeats and re-visions this exclamation of devotion, in the stitches that pierce the soft layers of the quilt carving out dips and furrows, creating shadows. These stitches are an intervention into the suffrage historiographies that have found the lesbian suffragette un-imaginable. The quilt imagines the un-imaginable, and claims the suffragette bed as a politically significant site for the re-working and queering of suffrage histories.

This quilt is one small intervention, and does not have the scope to uncover much additional information about Vera Holme’s life, instead focusing creatively on re-visioning one small gesture from the archive. Like a patchwork quilt, public memory is made up of many encounters and stories, accumulated over time. In order to queer suffrage history, this work must be pieced together alongside the voices of other lesbian suffragettes and suffragists through the contemporary re-visioning work of other activists, writers, and artists. Through the exhibition, I hoped to open up a space of dialogue, curiosity and compassion in the hope that more work will be done, and more queer love stories uncovered in the future.

Finally, this was only the anniversary of partial suffrage, the centenary for full British women’s suffrage of all classes falls in 2028. This will mark the year when the second instalment of the women’s suffrage bill ‘easily passed all the stages’ with little opposition. (Atkinson 2018: 522) I hope that we can take the opportunity to create different kinds of public programs that challenge perceptions of suffrage as a white, straight, middle class movement. This is our second chance, to celebrate and illuminate the full richness of the lives of queer, differently-abled and women of colour who fought for suffrage and equality.

Notes

[1] It was not until the Great Reform Act in 1832 that women were explicitly excluded from voting, while 300,000 more men were enfranchised. (Atkinson 2018: 3) Following John Stuart Mill’s repeated attempts to pass an amendment to the second reform bill, the National Union of Women’s Suffragette Societies was founded and led by Millicent Fawcett in 1897. The more militant Women’s Social and Political Union was then formed in Manchester in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, supported by her family. (Atkinson 2018)

[2] Others discussed include: disabled suffragette Rosa May Billinghurst, who founded the Greenwich WSPU branch and took part in the window smashing campaign of 1912; Sophia Duleep Singh, who handed out newspapers and was arrested; and her suffragist sister Catherine Duleep Singh who had a lesbian relationship with German governess Lina Schafer. (Braidwood 2018)

[3] The complexities of the emergence of the masculine lesbian cultural identity in Britain are excellently mapped in Laura Doan’s book: Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture. She situates the trial of Radclyffe Hall in 1928, in particular the images used by the press, as a tipping point in the popular association of masculine dress and lesbianism.

REFERENCES

Adamson, Glenn (2007), Thinking Through Craft, London: Bloomsbury.

Andersson, Jasmine (2018), ‘100 years after women were given the vote, it’s time to recognise lesbian, bi and queer Suffragists’, Pink News, 6 February 2018, https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2018/02/06/100-years-votes-for-women-suffragettes-bi-lesbian-queer/ (last accessed 16 June 2020)

Atkinson, Diane (2018), Rise Up Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes, London: Bloomsbury.

Auther, Elissa (2012), ‘Fiber Art and the Hierarchy of Art and Craft, 1960-80’, in Jessica Hemmings (ed), The Textile Reader, London: Berg, pp. 210–223.

Bradley, Katherine (2000), ‘Women’s Suffrage Souvenirs’, in Michael Hitchcock & Ken Teague (eds), Souvenirs: The Material Culture of Tourism, London: Aldershot, p. 87.

Braidwood, Ella (2018), ‘The Queer, Disabled, and Women of Color Suffragettes History Forgot’, Vice, 2 May 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/9kz54p/uk-suffrage-centenary-anniversary-women-color-queer-disabled-activists (last accessed 14 June 2020)

Bryan-Wilson, Julia (2017), Fray: Art and Textile Politics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Castle, Terry (1993), The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture, New York: Columbia University Press.

Chaich, John, & Todd Oldham (2016), Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community, New York: AMMO BOOKS.

Cohler, Deborah (2010), Citizen, Invert, Queer: Lesbianism and War in Early Twentieth-Century Britain, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dangerfield, George (1935), The Strange Death of Liberal England, London: Penguin Publishing Group.

Doan, L., & Garrity, J. (2006), Introduction, in Sapphic Modernities: Sexuality, Women and National Culture. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403984425

Dolan, Alice & Sally Holloway (2016), ‘Emotional Textiles: An Introduction’, Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 152–159.

Dunn, Thomas R. (2017), ‘Whence the Lesbian in Queer Monumentality? Intersections of Gender and Sexuality in Public Memory’, Southern Communication Journal, Vol. 82, No. 4, pp. 203–215.

Enszer, Julie R. (2016), ‘“How to stop choking to death”: Rethinking lesbian separatism as a vibrant political theory and feminist practice’, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 180–196.

Epp, Marlene (2008), Mennonite Women in Canada: A History, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Faderman, Lillian (1985), Surpassing the Love of Men, London: The Women’s Press Ltd.

Flood, Catherine & Gavin Grindon (2014), Disobedient Objects, London: Harry N. Abrams.

Ford, Sarah-Joy (2018), ‘Hard Craft’. Vane Gallery. https://www.vane.org.uk/exhibitions/hard-craft (last accessed 20 June 2020).

Freeman, Esther (2020), ‘Lesbian History – is it any of our business?’, Esther Freeman, 31 July 2020, https://esther-freeman.medium.com/lesbian-history-is-it-any-of-our-business-11bb2744a996 (last accessed 23 November 2020).

Golda, Agnieszka (2016), ‘Feeling: Emotional Politics Through Textiles’, in Hazel Clark, Diana Wood Conroy & Janis Jefferies (eds), The Handbook of Textile Culture, London: Bloomsbury, pp. 401–415.

Leeds Revolutionary Radical Feminists. (1981), Love your Enemy?: Debate between Heterosexual Feminism and Political Lesbianism, London: the Onlywomen Press Collective.

Hall, Lesley (2016), ‘Sentimental Follies or Instruments of Tremendous Uplift? Reconsidering Women’s Same-sex Relationships in Interwar Britain’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 124–142.

Hamer, Emily (2016 [1996]), Britannia’s Glory: A History of Twentieth Century Lesbians, Bloomsbury.

Jack Bratich Z. & Heidi M. Brush (2011), ‘Fabricating Activism: Craft-Work, Popular Culture, Gender’, Utopian Studies, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 233–260.

Jagose, Annamarie (2002), Inconsequence: Lesbian Representation and the Logic of Sexual Sequence, New York: Cornell University Press.

Jefferies, Janis (2017), ‘Cloth, Language and Contemporary Art Discourse’, in Sarah-Joy Ford (ed), Cut Cloth: Contemporary Textiles and Feminism, Leeds: PO Publishing, pp. 53–59.

Jeffreys, Sheila. (1989). Does it matter if they did it? In Not a passing phase: reclaiming lesbians in history 1840-1985 (pp. 19–29). London: The Women’s Press Ltd.

Jefferies, Janis (2020), ‘Textiles’, in Fiona Carson & Claire Pajaczkowska (eds), Feminist Visual Culture, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 189–206.

Kean, Hilda (2005), ‘Public History and Popular Memory: Issues in the Commemoration of the British Militant Suffrage Campaign’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 14, No. 3-4, pp. 581–602.

Kisby, Anna (2014), ‘Vera “Jack” Holme: Cross-dressing Actress, Suffragette and Chauffeur’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 120–136.

Kokoli, Alexandra M. (2016), The Feminist Uncanny in Theory and Art Practice, London: Bloomsbury.

Lapovsky Kennedy, Elizabeth & Madeline D. Davis (1993), Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (20th anniversary), London: Routledge.

Lesbians, Radical (1970), Woman Identified Woman, Pittsburgh: Know Inc.

Lippard, Lucy (1983), ‘Up, Down and Across: A New Frame for New Quilts’, in Charlotte Robinson (ed), The Artist and the Quilt, New York: Knopf, pp. 32–43.

Love, Heather (2007), Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mitchell, David (1977), Queen Christabel, London: The Book Service Limited.

Murphy, Gillian (2017, March), ‘Vera ‘Jack’ Holme – one of the stars of the Women’s Library Collection’, LSE Library Blog, 15 March, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsehistory/2017/03/15/vera-jack-holme-one-of-the-stars-of-the-womens-library-collection/ (last accessed 10 November 2021).

Oram, Alison & Annmarie Turnbull (2001), The Lesbian History Sourcebook, New York: Routledge.

Pankhurst, Christabel (1913), The Great Scourge and How to End It, London: Lincoln’s Inn House.

Parker, Rozsika (1984 [2nd ed]), The Subversive Stitch, London: IB Tauris.

Purvis, June (2013), ‘Gendering the Historiography of the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Britain: some reflections’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 576–590.

Purvis, June & Maureen Wright (2005), ‘Writing Suffragette History: The Contending Autobiographical Narratives of the Pankhursts’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 14, No. 3-4, pp. 405–433.

Roberts, Lacey Jane (2011), ‘Put your Thing Down, Flip it and Reverse it: Reimagining Craft Identities Using Tactics of Queer Theory’, in Maria Elena Buszek (ed), Extra/Ordinary Craft and Contemporary Art, Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 243–258.

Sally (2018), ‘British Suffragette History: Come for the Democracy, Stay for the Lesbian Drama’, Autostraddle, 17 April 2018, https://www.autostraddle.com/british-suffragette-history-come-for-the-democracy-stay-for-the-lesbian-drama-414891/ (last accessed 10 November 2021).

Sorkin, Jenni (2012), ‘Stain: On Cloth, Stigma and Shame’, in Jessica Hemmings (ed), The Textile Reader, London: Berg, pp. 59–67.

Thorpe, Vanessa & Alec Marsh (2000), ‘Diary reveals lesbian love trysts of suffragette leaders’, The Guardian, 11 June 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/jun/11/vanessathorpe.theobserver (last accessed 10 November 2021).

Tickner, Lisa (1988), The Spectacle of Woman: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-14, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Traub, Valerie (2010), The Renaissance of Lesbianism in Early Modern England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wiley, Christopher (2004), ‘”When a Woman Speaks the Truth about Her Body”: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and the Challenges of Lesbian Auto/Biography’, Music & Letters, Vol. 85, No. 3, pp. 388–414.

Wilton, Tamsin (1995), Lesbian Studies: Setting an Agenda, London: Routledge.

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey