Periperformative Speech & Performance of Sororidad in Jazmín Varela’s ‘Tengo unas flores con tu nombre’

by: Andrea Aramburú Villavisencio , March 30, 2023

by: Andrea Aramburú Villavisencio , March 30, 2023

The 3rd June 2015 was a significant day in the history of Argentinian feminism. It was on this date that a public demonstration against gender violence was called on the streets of Buenos Aires, one the aftermath of which would radically transform the workings of Latin American feminism. The movement behind this demonstration, known as Ni una menos (Not One [Woman] Less), arose in the context of a specific case of femicide, the murder of Chiara Páez, heavily mediatised within social media platforms. More broadly, it signalled women’s exhaustion in the face of generalised and long-lasting gendered violence. In Argentina, this particular form of violence had become an everyday staple that seemed to be ignored—even availed—by official and legal systems. In 2021 alone, 251 people were victims of gender-based violence; of this number, 231 were the direct victims of femicides. The statistics are considerably higher for some population groups, particularly indigenous and black women (Pérez-Rosario 2018: 283). Since 2015, Ni una menos—and its various powerful hashtags, such as #VivasNosQueremos and #NosMueveElDeseo—has become a region-wide feminist collective led by a young, fierce generation of women and trans, non-binary, and queer people battling this reality. Furthermore, the historical moment of buzzing, emergent, and timely resistance prompted by Ni una menos’ massive congregations has given rise to a graphic movement of art collectives making illustrations and comics, whose articulating axis is fighting against gender-based violence and oppression. This essay will draw on feminist and queer theory to examine one particular comic within this graphic panorama: Tengo unas flores con tu nombre (guía práctica de sororidad) by Argentine Jazmín Varela.

Born in 1988, Varela is a comics artist from Rosario and an active member of Cuadrilla Feminista, one example amongst this wave of graphic collectives. [1] Varela has published several fanzines, including ¿Para qué fumás? (2014) and Un peso, dos piezas (2015), as well as the books Crisis capilar (EMR, 2016), Guerra de soda (Maten al Mensajero, 2017), Tengo unas flores con tu nombre (guía práctica de sororidad) (Maten al Mensajero, 2018) and Cotillón (Maten al mensajero, 2020). Tengo unas flores con tu nombre (guía práctica de sororidad), with which this paper is concerned, is a non-narrative comic in which Varela collects portraits of women and queer people speaking phrases of support to each other. The aim of the following reflections is to explore Varela’s use of the comics medium to protest gendered violence in Argentina in 2018. The trajectory of my argument will follow two interwoven threads. I will focus on Varela’s use of drawn and spatialised text as periperformative speech, an aesthetic tactic that, I argue, is put to work in order to challenge the hegemonic frameworks that keep normalising violence against women in Latin America. At the same time, I will propose that Tengo unas flores… plays with the non-narrative potential of the comics medium to embody the performance of sororidad, understood as a specific practice of coalition and care of Argentinian feminisms.

***

A Brief Note on the History of Feminist Comics in Argentina

Before proceeding with the analysis, it is key to contextualise Varela’s work within a genealogy of feminist comics in Argentina. An important piece on the history of feminist comics across the region was published in 2016 in the online Spanish comics journal Tebeosfera. The article, titled ‘Historieta feminista en América Latina: autoras de Argentina, Chile, Brasil y México’, compiled texts by a group of country-specific scholars of the medium, namely Mariela Acevedo (Argentina), Katherine Supnem (Chile), Gabriela Borges (Brazil), and Maira Mayola (Mexico), each surveying the now-blooming Latin American feminist comics panorama. In relation to Argentina, Acevedo situates the early days of feminist comics within the publication of Fierro, a comics magazine first released in 1984. Fierro, according to Acevedo, began to publish women authors who now belong in the feminist canon of national comics, such as Maitena and Patricia Breccia. The magazine also featured work by Diana Raznovich, Ana Von Rebeur, Alicia Guzmán, and Silvia Ubertalli, amongst others, bringing their names into the mainstream comics industry (2016). Nonetheless, as Acevedo rightly asserts, these authors still occupied a marginal position within a male-dominated panorama, and (for example) during the magazine’s first period, none of them was offered a cover to illustrate and sign with their own name (2016).

Taking a similar perspective, in their article ‘Chicks Attack! Making feminist comics in Latin America’ Amadeo Gandolfo and Pablo Turnes contend that ‘[h]istorically, female comic creators in Argentina have occupied a subordinate and even anonymous position in comparison to their male counterparts’ (2020: 2). In the context of this assertion, the pair open their essay by rescuing the names of cartoonists Ada Lind, Martha Barnes, and Blanca Cotta as three authors who were making comics as early as the first half of the twentieth century, and whose work has been little documented. Gandolfo and Turnes also include some of the names recognised by Acevedo, as they characterise the 1980s as a ‘decade [that] saw the appearance of several important women cartoonists in tune with the growing and expansive feminist movement of the 1970s’ (2020: 2).

Indeed, the last decades of the 20th century paved the way for the blossoming Latin American comics scene that came with the new millennium. This was a cultural panorama at the intersection of the global and the local, of which feminism was a crucial tenet. The scene heralded by artists such as Powerpaola in Colombia, Marcela Trujillo (Maliki) in Chile, and Amadeo and Renso Gonzales (editors of the magazine Carboncito) in Perú, has expanded over the past decade with a growing number of high- and low-brow publications. Chicks On Comics, an online dialogue about gender-related issues in comics form, was founded in 2008 by Powerpaola and Joris Bas Baecker. The group has now become one of the best-known international comics collectives, of which several members are from Latin America. During the 2010s, a number of feminist comics magazines were released, such as Tribuna Femenina Cómix (Chile, 2009-2012), Clítoris (Argentina, 2011-2017), and Brígida (Chile, 2018-). In Argentina, we highlight the role of Clítoris, edited by Acevedo, which was published for the first time in 2011 and very soon became a key output for showcasing the work of the new generations of feminist authors, including the work of women, non-binary, trans, and queer people (Gandolfo and Turnes 2020: 3). Similarly, the Vamos las pibas! festival, created in 2017 and still going on today, was one of the first DIY, self-managed spaces where women and dissident populations could exchange, sell, and share their comics and fanzines, discovering each other as referents, far from the normative parameters and patriarchal restrictions of the mainstream.

The contemporary feminist comics scene in Argentina to which Varela belongs shares many characteristics with what Charles Hatfield has termed ‘alternative comics’ in the US and Canada. Hatfield uses this term to refer to a set of works that introduced into the comics market an ‘unprecedented sense of intimacy’ (2005: 7) and ‘potential for radical cultural argument’ (2005: 114). In his monograph, he argues that because alternative comics play with ‘the frontiers of self-exposure, spotlighting their own manias and fears,’ they bring onto the page a ‘harrowing intimacy’ that ‘authenticates their social observations and arguments’ (2005: 114). However, even if the scene that concerns me presents a sense of radical intimacy similar to that which is noticed by Hatfield, it ought to be noted that this intimacy is especially linked to the artists’ gendered experience. In keeping with this, the contemporary comics scene in Latin America can perhaps better be identified as heirs to feminist underground comix made by collectives in the 60s and 70s such as Tits and Clits, Wimmen’s Comix, and Twisted Sisters (which, amongst other things, criticised the patriarchal gaze of their male colleagues). Susan Kirtley, for example, claims that feminist underground comix became popular in tandem with the rise of second-wave feminism in North America; they ‘proffered a form perfect for self-examination and analysis, echoing the notion that the “personal is political”’ (2018: 271). She continues by saying that ‘feminism invited artists and authors to investigate the importance of one’s own experience, confront inequities large and small, and, in the process, render a more comprehensive understanding of the problems of society, all while depicting a vision of a new world marked by possibility and promise’ (2018: 283). In many ways, these collectives modelled the politics of the ordinary that I associate with feminist Latin American comics.

We must remember, nonetheless, that feminism has had its own trajectory in Latin America. Varela may have a similar aesthetics to that of Trina Robbins, yet her comics are produced and received in the specific context of contemporary feminisms in Argentina. Such specificity links her work to Ni una menos, for example; however, when we read her work as feminist, we must also place it within a longer history of distinct women’s movements in the country, such as Las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo, who protested the military regime of the 70s, and the thousands of people disappeared by the government at the time. Keeping this in mind, when reading Varela’s feminist comics, one may need to ask, as Claudia Andrea Bacci does in her article ‘Ahora que estamos juntas,’ how we conceptualise feminist temporalities desde el cono sur? (2020: 5). Looking at the comic’s own subtitle — ‘(guía práctica de sororidad)’—may be a suitable starting point to approaching this complex task.

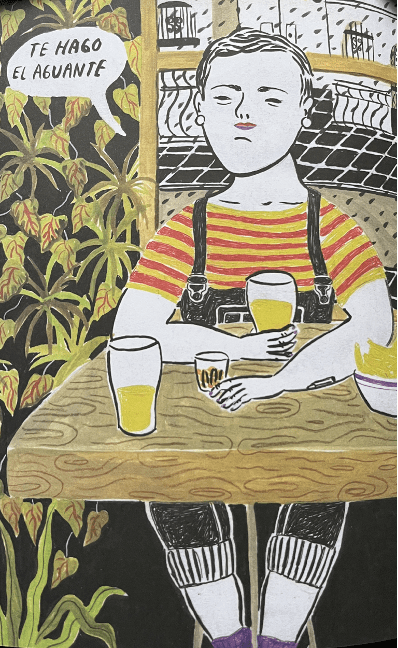

Latin American Sororidad

In Latin American feminist politics, the concept of sororidad differs from the North American use of ‘sorority,’ a term that conventionally refers to women’s circles within universities in the USA. While sororidad is closer to what US feminists in the 60s called ‘sisterhood,’ the concept has a special focus on the question of difference. For Bacci, ‘sororidad’ implies ‘[un] carácter ético [que] propone prácticas de cuidado frente a las diversas formas de violencia contra las mujeres, sexual y de género’ (‘[an] ethical character [that] proposes practices of care in the face of the various forms of violence against women, sexual and gender-based violence’) (2020: 3). [2] At the same time, the practice of sororidad is recurrently challenged by the fact that what falls under the category of women is a heterogeneous group of individuals with different struggles and histories. Bacci therefore affirms that ‘la cuestión de la diferencia tensiona de inmediato la unidad imaginaria de “las sororas”’ (‘the question of difference immediately strains the imaginary unity of “las sororas”’) (2020: 7). While hegemonic notions of sorority coined in the Global North emphasise seamless unity within a common context, the concept of sororidad points to a network of mutual care across a variety of positionalities and living situations. The title given to the present piece—‘Te hago el aguante’—is taken from one of the comic’s portraits (Fig. 1), for it appropriately captures the nuances of sororidad as a specific practice of coalition proper of Argentinian feminisms. ‘Te hago el aguante’ is an Argentinian expression used to voice support for someone else, where aguante figuratively emphasises the physicality of carrying or holding the other’s experience as it is. The phrase, therefore, gives way to an embodied, caring form of resistance in the context of difference.

Ordinary Struggles

In Tengo unas flores con tu nombre, Varela puts together 20 portraits of women in their everyday lives speaking words of support to each other, such as the previously cited ‘Te hago el aguante.’ In an interview with El Ciudadano, Varela explains that the idea came after a conversation she held with a woman taxi driver who was taking her home late at night. It occurred to her to assemble a comic doubling as a guía práctica de sororidad, picturing women offering words of support to each other. She started carrying a diary notebook, where she would write down phrases she heard from her friends or on the radio, that she read on the internet, or that came up in conversations with her family (Varela 2018b).

Varela’s work lingers in the liminal space between the autobiographical and the fictional. She evokes a reality that, while of global reach, points particularly to a Latin American context, and more specifically to Argentina in 2018. Central to this setting, as mentioned in the introduction, is the increasing number of femicides in the country. The Informe de Femicidios de 2018 published by the Argentinian government states that there were 275 victims of femicides in that year alone (2019: 8). In a volume on artistic interventions surrounding Ni una menos, entititled Recuperar la imaginación para cambiar la historia (Proyecto NUM), ‘feminicidio’ (‘femicide’) is defined as ‘mujer asesinada por un hombre que la considera su propiedad’ (‘woman killed by a man who considers her his property’) (2017: 68-69). The focus on proprietorship in this definition foregrounds the fact that femicide is part of a larger patriarchal structure built upon asymmetrical and gendered power relations. As Rita Segato writes in her article ‘Colonialidad y patriarcado moderno,’ ‘las relaciones de género son, a pesar de su tipificación como “tema particular” en el discurso sociológico y antropológico, una escena ubicua y omnipresente de toda vida social’ (‘gender relations are, despite their typification as a “particular subject” in sociological and anthropological discourse, a ubiquitous and omnipresent scene of all social life’) (2014: 76).

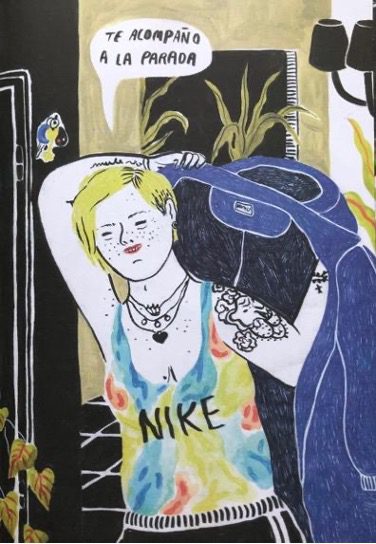

Figure 2. Words of sororidad, in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

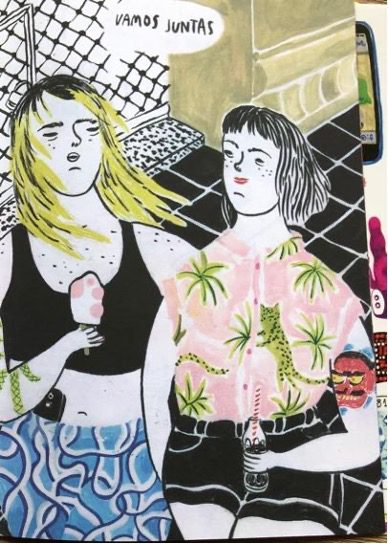

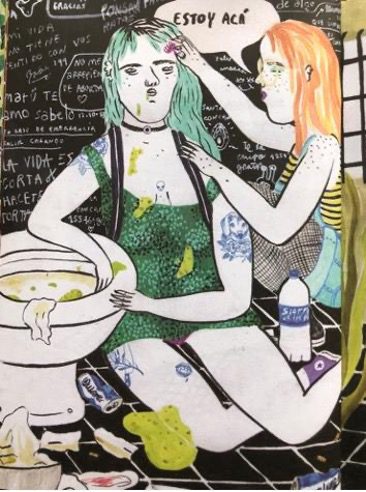

The portraits in Tengo unas flores belong in the kind of social life of which Segato writes. They represent ordinary lived experience between friends, while evoking a context in which each added femicide matters and perpetuates a patriarchally-upheld system of violence. The phrases included in the comic are words of support that point to the all-encompassing gender violence that takes over the characters’ ordinary lives, yet do so from a tangential angle. For example, one of the portraits shows a woman about to leave her house, as she says: ‘Te acompaño a la parada’ (‘I’ll walk you to the bus stop’). Another one shows two women arm-in-arm. One of them says: ‘Vamos juntas’ (‘Let’s go together’) (Fig. 2). A further one shows a woman combing her friend’s hair next to the toilet seat of a public toilet, where the latter has been sick. She says: ‘Estoy acá’ (‘I’m here’) (Fig. 3). The wall behind is covered with writing in the form of phrases and tags, featuring expressions such as ‘No me arrepiento de abortar’ (‘I don’t regret having an abortion’), ‘La vida es corta y hacete torta ’(‘Life is short: become torta [lesbian],’ or just glimpses of some statements saying ‘Gracias’ (‘Thanks’) or ‘Todas estamos recuperándonos de algo’ (‘We are all recovering from something’).

Figure 3. Feminist wall, in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

In this panel, the proliferation of messages that only indirectly—if at all—reference the notion of femicide echoes how, in the years after 2015, the slogan ‘Ni una menos’ was translated into a multiplicity of phrases populating the banners at demonstrations, carrying a set of demands ‘that questioned different aspects in which machismo manifests itself in society’ (Abbate 2018: 148). In this manner, the phrases selected by Varela reflect on how the women’s movement in Latin America has since 2000 distinguished itself by articulating an array of struggles, such as those related to sexual dissidences, queer and trans groups, ‘questioning essentialisms, appealing to the deconstruction of the sex/gender system, and to all relations of domination that seek some kind of determination over individuals, re-signifying social institutions such as work, education and medicine’ (Lamadrid Alvarez & Benitt Navarrete 2019: 7). The comic thus shows that even if Ni una menos emerged as a phenomenon articulated around specific and mediatic cases of femicide, as a movement, it quickly became an axis to spotlight and bring awareness to other gender issues and pressing demands. Here, gender-based violence is imagined as a significant part of a patriarchal social fabric that encompasses the spheres of productive and reproductive labour. In the words of Marina Larrondo and Camila Ponce in their edited collection Activismos feministas jóvenes: emergencias, actrices y luchas en América Latina,

Además del pedido básico ‘Vivas nos queremos,’ los colectivos feministas avanzan sobre la denuncia de prácticas discriminatorias en torno al trabajo y la desigualdad salarial, la denuncia en torno al acoso laboral, callejero, el derecho al acceso al aborto, la visibilidad y el reconocimiento de las disidencias sexuales entre otras demandas. En nuestra región, al movimiento feminista y a las demandas y reivindicaciones de género—en numerosos colectivos—se suman aquellas de clase y las demandas étnicas que han estado presentes históricamente (2019: 21). [3]

This continuous proliferation of demands underlines how, even if the feminist movement in Argentina has achieved several victories (for example, the legalisation of abortion in 2020, after a 5-year long battle, as well as the creation of the Registro Nacional de Femicidios de la Justicia Argentina (RNFJA) and the Unidad de Registro, Sistematización y Seguimiento de Femicidios y de Homicidios Agravados por el Género), [4] the situation of everyday violence lived by women has not seen drastic and systemic changes. The phrases collected by Varela, in this sense, portray situations that, at first glance, may seem cheerful and merely ordinary. However, when read more closely and in relation to each other, they offer testimony of the daily, shape-shifting violence that continues to be experienced by women and gender non-conforming minorities, in spite of the movement’s many victories.

By proposing to read the phrases in Varela’s comic ‘more closely,’ I build on Hannah Miodrag’s theorisations on the medium as outlined in Comics and Language. Miodrag argues that ‘comics’ writing operates according to a mode different from prose or poetry’ (61), and that the forms in which text is placed on the page are more relevant to some comics than others. For instance, she uses the example of North American cartoonist Lynda Barry as a comics artist who puts words to work in a very literary manner, and who is ‘ill-served by a conception of the form that sidelines textual content’ (2013: 41). For Miodrag, text in comics, like images, can be equally made spatial within configurations whose purpose exceeds adding dialogue or storyline to the illustrations. She thus encourages the reader to examine if a comic may be demanding a kind of engagement that would look beyond the image-text relationship that can occur between a drawing and its narrative caption. Following Miodrag’s lead, one can argue that Varela’s Tengo unas flores is a comic in which the text is central and thus demands a specific kind of analysis.

If we return to Varela’s bathroom wall portrait (see Fig. 3), we can begin to outline the kind of analysis that, I argue, the comic demands. The drawn and tagged wall that stands behind the characters can be read as a feminist canvas evoking the overall interwoven structure of the comic itself, where utterances from different contexts are brought together within the same material space. Here, Varela creates a collage effect through techniques of assembly, although this may not strictly be a collage in its narrowest definition (it does not use mixed media). Similarly, each of the phrases spoken by her characters, even if laid out in sequence, encourage the reader to picture them spatially with and against each other, so within this ‘collaged’ arrangement they can acquire further significations. Eve K. Sedgwick’s concept of the ‘periperformative,’ to which I now turn, is a useful tool to understand how ordinary phrases are spatially related in Varela’s comic.

Periperformative Speech

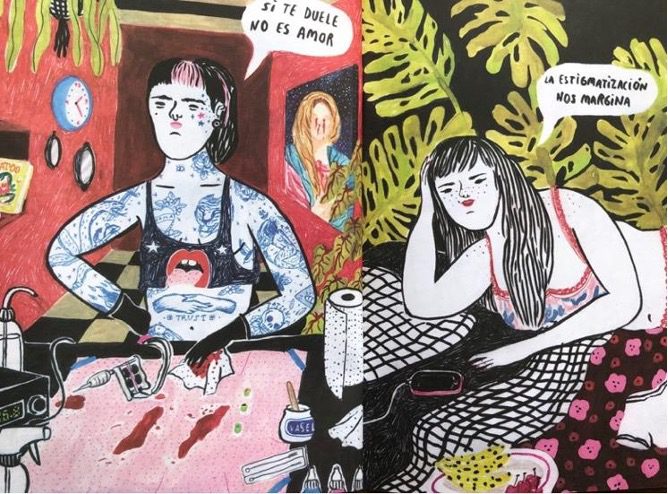

Sedgwick, drawing on J. L. Austin’s theorisations of speech acts and Judith Butler’s ideas on the performativity of gender, coined the concept of the ‘periperformative’ to refer to acts that are ‘in the neighbourhood of the performative’ (2003: 68). Anna Poletti explains this term’s workings clearly: she writes that the periperformative, in spatial proximity to the performative, ‘seeks to disentangle its speaker from the assumed consensus that emanates from the performative utterance and its speaker’ (2016, 368). In other words, the ‘periperformative’ alludes to, but also challenges, the implicit unanimity on a usually hegemonic matter. In Varela’s account, the phrases collected are not in direct dialogue with each other, in what it would otherwise be a collective consensus. Instead, phrases such as those shown in Figure 4—‘Si te duele no es amor’ (‘If it hurts, it’s not love’) and ‘La estigmatización nos margina’ (‘Stigmatisation marginalises us’)—each respond in their own context to a specific experience of violence against women. It is, therefore, their periperformativity in relation to gendered violence which assembles them as a common set of utterances. In this interpretation, violence against women is read as a generalised and performative context, which has become the norm by way of repetition and naturalisation.

Figure 4. Periperformative utterances in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

I do not claim that these phrases are not performative speech acts in themselves. If we take Sedgwick to the letter, many of them are exactly this, because they use the ‘first-person singular present indicative active form that would signal a performative act’ (Sedgwick 2003: 78). Promises of care, and statements of support and companionship are made when someone says ‘Yo te creo’ to another woman (see Fig. 5). What I am arguing is that these speech acts are not spatially sustained by the same ‘relations of visibility and spectatorship’ (Sedgwick 2003: 72) that underpin other authorised performative utterances, particularly those that belong to the frameworks of the heteronormative, such as heterosexual marriage, for example. In the context of the latter, an ‘I do,’ or even an ‘I love you,’ is lawfully welcome to be pronounced explicitly both within private and public settings. Instead, the words featured in Tengo unas flores, using Sedgwick’s phrasing, are closer to being ‘negative performatives:’ ‘marked, in almost every instance, by the asymmetrical property of being much less prone to becoming conventional than the positive [ones]’ (2003: 70).

Figure 5. ‘Yo te creo,’ in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

Reading the comic’s utterances as ‘periperformative’ implies recognising, firstly, that these words are not uncalled-for and, secondly, that Varela has not arbitrarily grouped them together. Instead, these phrases surround a complex, gender-based, violent framework which, as referenced, has historically been—and continues to be—the norm in Latin American countries such as Argentina. Even if phrases such as ‘Yo te creo’ (‘I believe you’) and ‘Vamos juntas’ (‘Let’s go together’) (Fig. 5), placed within frames alongside each other, do not reference the same act of violence, they do respond to a systematic oppression that has been naturalised and institutionalised; ‘they cluster around [it], they are near [it] or next to [it] or crowing against [it]’ (Sedgwick 2003: 68). The historical course during which gendered violence became ingrained within Latin American societies is overdetermined by racism, capitalism and colonialism, as Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, Diana Gómez Correal and Karina Ochoa Muñoz write (2014: 16). [5] In particular, the complexity of these interwoven structures of power can be traced back to the process of the primitive accumulation of capital as Europe expanded and conquered the continent. This process, as Alejandra Ciriza writes, came ‘a expensas de la desposesión y sometimiento a servidumbre y esclavitud de miles de seres humanos cuya humanidad fue puesta en cuestión,’ amongst whom were women (Ciriza 2018: 67). [6]

Contemporary legal systems in Latin America, in this sense, are built on the basis of this historical framework in which what should be the dehumanising exception has become the norm. In the terms used by Giorgio Agamben, governments become ‘states of exception’ (2005) in which laws are organised in a system which has space for the rights of some but excludes those of anyone deemed other. Argentina, in particular, has a recent history of military state repression in which the guarding of the heteropatriarchal family became a building-block to justify a political rhetoric of exception and repression. In this context, the need to say to the other I believe you or I’ll come with you to care for your well-being is a configuration of the social, as Segato affirms, that is constituted by forms of gendered violence that are not effectively addressed by legal systems (2014) or that are indeed justified in their absence. Because gendered violence is often condoned by the institutions regulating structures of desire—such as the law and the church—which often turn a blind eye to femicides, the expression of everyday solidarity amongst women emerges as a way of taking things into our own hands.

Another way to put it would be to say that the resistance represented by Varela in her assemblage of phrases is ‘periperformative’ because it belongs to an autonomous current of feminism. Silvia Lamadrid Alvarez and Alexandra Benitt Navarrete, writing in the context of Chile but applicable to the region as a whole, point out that feminism in Chile is fragmented between, on the one hand, an ‘institutional’ current, linked to the state and the regulation of public policies, and, on the other, an autonomous one (2019: 2). For the authors, this division limits the effectiveness of the action of the autonomous current, whose demands may be massive, mediatic and powerful, but remain far from generating changes in the institutional sphere (Lamadrid Alvarez & Benitt Navarrete 2019: 3). Even if an autonomous feminism may be operating at the level of ordinary life, what remains protected by the law and the institutional sphere are the rights which protect the heteropatriarchal notion of the ‘family.’ It is important to note here that what may be admitted in the institutional category can take many shapes. For example, while there has been considerable progress on women’s issues, sexuality, and gender identity in the last two decades since the so-called pink tide governments, [7] as Elisabeth Jay Friedman and Constanza Tabbush point out, ‘the engagement of left parties with issues of class, gender and sexuality could be characterised as rather ambiguous’ (2020: 27). While there were exceptions, such as the case of Uruguay, [ 8] many pink tide governments promoted the legalisation/institutionalisation of the most media-friendly issues at the international level, such as same-sex marriage, while relegating those related to women’s reproductive rights and the context of ongoing gendered violence (27).

In this sense, we may say that the promises to care for the other represented by Varela are oriented toward the project of surviving a historical context of violence, a crisis-shaped ordinary, where women are required to be constantly ‘cobbling together ways to attach to the world that cannot be subsumed into an identity or bionarrative’ (Poletti 2016: 376). By drawing attention to the periperformativity of the ‘Yo te creo’ (Fig. 5), beyond the identitarian space or specific life story located at the other side of the conversation, Varela makes a powerful move: she highlights the survival structure that a web of autonomous sororidad can provide to victims, however precarious this may be. In the face of a lacking system of governmental and official support, the characters in Tengo unas flores speak up and stand together.

Another way to understand how this space works is to put it in the terms of Jacques Rancière, as done by Florencia Abbate in her writings about the Ni una menos demonstrations in Argentina. Abbate follows Rancière in distinguishing between the concepts of ‘police’ and ‘politics.’ For Rancière, the police make use of power devices to determine the division of bodies and their societal roles, or as she puts it, ‘un orden de lo visible y lo decible’ (‘an order of what may be visible and sayable’) (2018: 149). The police, then, in Sedgwick’s terms, would correspond to the performative sphere, to that which is endorsed by institutional discourses. Meanwhile, politics, in Abbate’s reading of Rancière, corresponds to ‘una actividad antagónica al orden policial’ (‘an activity antagonistic to police order’), an action of disidentification and dissent that carves out space for new subjectivations to emerge (Abbate 2020: 149). Varela’s characters flourish in the space of politics. Their utterances of care unsettle the workings of the institution and their conventional ideas of ‘support,’ built upon compulsory heterosexuality and what this notion implies on a normative and ideological level (Abbate 2020: 153).

Relatedly, a final point to highlight here is the format chosen by Varela in her comic: the ‘guía práctica de sororidad’ (‘a practical guide for sororidad’). The format echoes the pamphlets published by autonomous feminist organisations in contexts in which institutions are absent or inadequate regarding issues of feminist care. Therefore, ‘practical guides’ are published and distributed in DIY activist spaces; these can include, for example, instructions to learn how to have an abortion with pills at home, or how to recognise cases of domestic violence camouflaged under the patriarchal notion that ‘love hurts’—hence Varela’s phrase ‘Si te duele no es amor’ (‘If it hurts, it’s not love’). In keeping with this, Tengo unas flores can be placed within a genealogy of feminist comics in Argentina that reappropriate the manual or practical guide format, such as a comic by Diana Raznovich with texts by Lucrecia Oller, published in 1989, entitled Manual de instrucciones para mujeres golpeadas (Manual of Instructions for Battered Women). [9] According to Acevedo, the Raznovich manual ‘remite a las demandas feministas de visibilizar las agresiones contra mujeres en manos de sus parejas y exparejas como expresiones de una violencia estructural de carácter patriarcal’ (‘refers to feminist demands to make visible the aggressions against women at the hands of their partners and ex-partners as expressions of a structural violence of a patriarchal nature’) (2020: 13). Similarly, Varela’s ‘guía práctica de sororidad’ reworks the format of the manual. However, while the former makes visible a chilling experience for women, the latter draws attention to the network of care that clusters around that frightening reality—periperformatively we may say. Here, violence is only referenced adjacently. Caring actions and utterances take centre stage, embodying a practice of sororidad grounded in community and love. It is towards this alternative subjectivation that I now look.

A Loving Collective

Varela’s comic portrays collective action not only in relation to a brutal context of gender-based everyday violence, but also in tune with the love and camaraderie that has characterised Latin American feminism over the past decade. Borrowing the words of Mariella Peller and Alejandra Oberti, we may say that her representations not only ‘marcan la trama social que produce las violencias—y sus responsables—sino que también despliegan políticas de resistencia que permiten a las mujeres imaginarse más allá de victimizaciones en un colectivo amoroso’ (‘mark the social fabric that produces violence—and those responsible for it—but also deploy politics of resistance that allow women to imagine themselves beyond victimisation in a loving collective’ (Peller and Oberti 2020: 1). Via the use of periperformative phrases, Varela tackles the spatial aspect of the movement’s politics of resistance. However, her collection of utterances has further aesthetic effects on the reader. Turning again towards Miodrag’s encouragement to observe ‘how comics’ use of words has recourse to particular visual-verbal effects’ that may not be pictorial at all, we may also point out that the comic uses short statements (the majority of them having between three or four words) to ‘control the reading pace, effectively inscribing comic timing on the page’ (Miodrag 2013: 77). For the reader, this creates a flow, as though in each portrait the characters were replying to what the other were saying, although they do not share the same spatio-temporal context. An alternative possibility of enunciation is created amongst women, in a series in which each of them can take the other as referent and interlocutor. The weaving of the textual within a thread that remains multiple highlights that it is not a matter of who takes the (hegemonic) centre stage when speaking, but rather of building a network of sororidad in which all women can speak and be heard.

By means of its paced rhythm, Varela’s comic also gestures towards the repetition of songs and phrases in loop during a demonstration. The phrases perform textually a form of public refusal that is articulated as celebratory and sororal, like the forms of organisation we have seen across Latin American countries over the past decade (Bacci 2020: 2). Examples include the aforementioned Ni una menos, which was replicated across the region, or the performance by the Chilean interdisciplinary feminist collective Las Tesis in 2019, initiated to protest against repeated instances of sexual assault by the police and the state during public demonstrations against the government of Sebastián Piñera. The performance of Las Tesis was also replicated and adapted to various regional contexts. Of the latter, Bacci writes that, ‘en Argentina, su apropiación introdujo el reclamo por la despenalización y legalización del aborto; en Perú, se replicó en quechua (Cusco); en Brasil, se agregó la pregunta ‘¿Quem matou Marielle [Franco]? Seu legado está presente!’ (Florianópolis)’ (‘in Argentina, its appropriation introduced the demand for the decriminalisation and legalisation of abortion; in Peru, it was replicated in Quechua (Cusco); in Brazil, the question “Who killed Marielle Franco? Her legacy is present!’ was added’) (2020: 5).

The repetition of what was started by Las Tesis throughout Latin America, according to Bacci, ‘señalaba la transversalidad generacional y étnica de estas violencias’ (‘pointed to the generational and ethnic cross-cutting nature of this violence’) (2020: 4). In Varela’s comic, we can also note how the phrases she uses can be read alongside other contexts beyond Argentina. The use of concise phrases such as ‘Yo te creo’ (‘I believe you’) or ‘Te espero hasta que entres’ (‘I’ll wait for you until you get inside’) evokes a context of gendered violence that transcends borders. Their claims produce a feminist ‘reverberation,’ in the sense used by Joan W. Scott and referenced by Bacci—that is, they trace ‘el modo en que circulan y se conectan estrategias y conceptos feministas cuyos sentidos se adaptan y transforman en diferentes contextos, generando solidaridades anacrónicas que reacomodan la unidad (siempre ficticia) entre las mujeres’ (‘the way in which feminist strategies and concepts circulate and connect, whose meanings are adapted and transformed in different contexts, generating anachronistic solidarities that rearrange the (always fictitious) unity among women’) (Bacci 2020: 4).

National & Transnational Sororidad

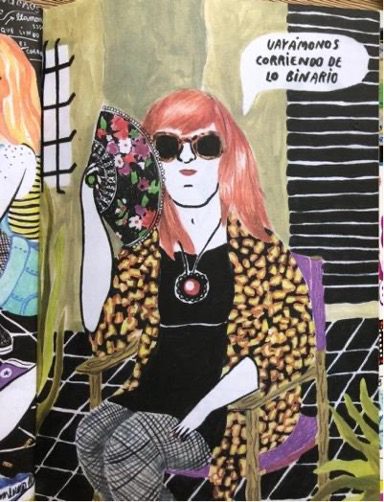

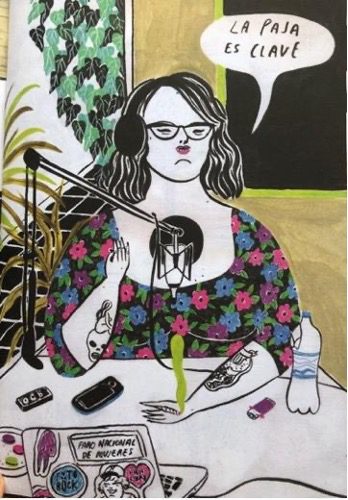

In relation to this last point, we may signal the ways by which Tengo unas flores builds its aesthetics of sororidad as it threads together national and transnational references that allude to different expressions of feminism. The comic presents itself as a cultural object codifying itself through certain co-ordinates of identity politics, as a product of a historically situated and specific aesthetics of ordinary life, that of Argentina in 2018 from Varela’s perspective. The series of portraits includes feminist icons and generational references that are specific to the context of feminist millennials in Argentina. Lozano’s women listen to the same music (Futurock) and to the same revolutionary podcasts (like that of Señorita Bimbo’s reminding them the importance of masturbation; ‘La paja es clave,’ she says). They follow Georgina Orellano, a sex worker who leads the fight for the rights of her community, and Susy Shock, artist and trans activist (Fig. 6). By embedding the comic in Argentinian pop culture, Varela makes the reader aware that, in 2018, the wider feminist revolution was reverberating locally. She is also suggesting that politics and culture are not processes that can be thought of independently of each other. In some manner, this becomes a self-referential claim: she is highlighting the importance of her own comic, and art practice more broadly, as tools of intervention within the activist sphere.

Figure 6. A struggle of a generation, in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

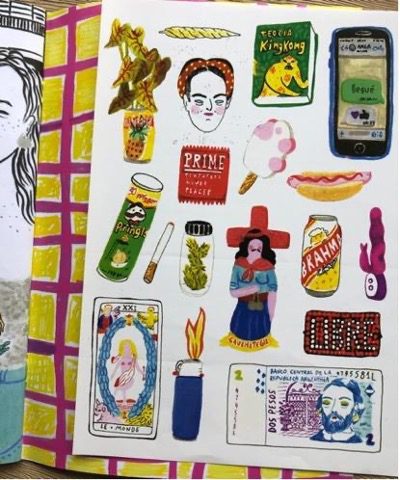

At the same time, the comic comes with an add-on sticker plate featuring an array of images that contrast with this ‘localised’ representation, pointing instead to a much more internationalised version of feminism. The page of loose stickers, shown in Figure 7, inscribes the comic within a globalised feminism ‘without borders’ by alluding to transnational referents of the feminist movement that have been successfully made ‘international:’ the manifesto King-Kong Theory (2006) by French Virginie Despentes, a key book on feminist politics with an international readership; a phone with a text message saying ‘Ya llegué’ (‘I’ve arrived’); and a cartoon version featuring the US icon Rosie the Riveter who says, ‘We can do it’—amongst other equally ‘internationalised’ yet not politically charged images, such as a can of Pringles. The reverberation of these referents falls differently than the more ‘local’ ones cited earlier. These are images that present feminism as a global, generational struggle, and therefore risk losing the specificity of difference that is key to the concept of sororidad. Instead of presenting feminism via an array of ever-changing cultural referents that matches the heterogeneity of its own struggles, these images rather seem to portray feminism as a commodified phenomenon, co-opted into a massive movement that erases alterity. The fact that these take the form of stickers, products whose purpose is to circulate amongst peers and various surfaces, foregrounds how these are referents that have been deterritorialised, removed from the particularity of a community or local context, to become part a global popular culture. The inclusion of these referents prompts us to ask, borrowing Malena Nijensohn’s words in La razón feminista, about the complex crossroads at which contemporary mass feminism finds itself:

¿Cómo podrían los feminismos hoy en día esbozar estrategias de resistencia que no queden atrapadas en las coordenadas neoliberales en las que se encuentran insertos? Pues este feminismo masivo, al mismo tiempo que se posiciona en contra del neoliberalismo, se encuentra en el neoliberalismo. (2019: 25). [10]

In the context of this question, it is striking that none of the actual bodies in the comic have been coloured, maintaining the same skin tone (paper white) in all characters. Although we can read this decision as related to Varela’s specific style, it may come across as a lack of engagement in an important aspect of the battle she is fighting, that of intersectionality and race representation.

Figure 7. International feminism, in Tengo unas flores (Varela)

Bearing in mind that any representation of alterity will always already be challenged and questioned by power relations, we can return to the way in which Varela is figuring the project of sororidad in Argentina. Overall, Varela’s representation of sororidad creates a powerful feminist message built upon phrases of support that reverberate transnationally and which, read alongside Sedgwick, make visible the context of violence confronted by women and dissidents everywhere. Yet it is important to acknowledge that her figurations of the movement come from a social perspective that is specific to a particular population group—the middle-class, or Varela’s circle of acquaintances and references—and that feminism and violence are not lived by all women equally. Reading the comic with this in mind can remind us that we must ask ourselves, again and again, how women and dissident subjects can be in relationship with each other while supporting a feminist struggle that recognises difference. This is what Ahmed implies in Living a Feminist Life when she speaks of feminism as a ‘project’ always in the making, ‘because we still have not reached that point’ (2017: 30). As Bacci also points out, in Latin America, the feminist project of sororidad is constituted by a heterogeneity that at times, and for some, can be difficult to acknowledge, because it may imply recognising privilege; ‘cada vez que la diferencia surja como ruptura’—so she states—‘el feminismo debería preguntarse “¿Quiénes podemos llegar a ser estas feministas que somos?”’ (‘whenever difference emerges as rupture … feminism should ask “Who can become these feminists we are?”’) (2020: 12).

Conclusions

My aim over the course of these reflections has been to consider Varela’s use of the comics medium to both portray and imagine the project of sororidad. By exploring the nuances of this concept in relation to Latin American realities, I have asked about the trajectories of feminism desde el cono sur, and how these take shape in a comic such as Tengo unas flores. I have read the comic as a collection of portraits and periperformative speech showcasing how contemporary feminist struggle is permeated by ordinary violence as much as it is constructed upon autonomous and loving care. Varela’s phrases are periperformative because they are represented, across ordinary life, as adjacent to a deeply ingrained context of gendered violence. Because this context is only present in an indirect manner and relates differently to each utterance, the assembly of these words within the same space is then able to take further significations. In this way, the comic portrays Argentinian feminism and its project of sororidad as a loving collective, characterised by its heterogeneity, and marked by an intention to recuperate alterity and care with political intent. However, as I have considered towards the end of the essay, the comic also brings us to think about the proliferation of certain feminist referents within an international version of the movement, and the risks that such commodification may pose, such as the erasure of alterity. Overall, Varela’s graphic work, as I have shown, is particularly significant because it allows us to understand the feminist project of resistance both as unified and containing points of rupture.

Notes

[1] Cuadrilla Feminista is a collective from the city of Rosario, created in October 2017, bringing together 17 comics artists, illustrators and graphic designers. One of the group’s initial actions was to make and distribute posters with feminist slogans, designed for wallpapering the city walls. Another prominent example is Línea Peluda, created in 2018 through social networks. Línea peluda is made up of women, non-binary people, and trans people In support of the struggle for legal, safe, and free abortions (Iribarren 2019: 508).

[2] All translations from Spanish are mine.

[3] ‘In addition to the basic demand “We want us alive,” feminist collectives are making progress in denouncing discriminatory practices related to work and wage inequality, workplace and street harassment, the right to access abortion, and the visibility and recognition of sexual dissidence, among other demands. In our region, the feminist movement and the demands and demands of gender—in numerous collectives—are joined by those of class and ethnic demands that have historically been present.’ (2019: 21)

[4] See https://www.argentina.gob.ar/derechoshumanos/proteccion/genero/unidad-de-registro.

[5] For a more updated account of the intersectional categories underpinning contemporary feminist Latin American thought, see also Trayectorias Del Pensamiento Feminista En América Latina, edited by Julia Antivilo, Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2022.

[6] See Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch (2004) for a feminist-Marxist account of reproductive work as part of the process of capital’s primitive accumulation. In the landscape of contemporary capitalism, see also Federici’s Witches, Witch-Hunting and Women (2018).

[7] At the beginning of the 21st century, Latin America went through what was internationally known as ‘the pink tide,’ a period lasting about 10 years, during which many of its governments turned to the left (Friedman & Tabbush 2020). In the context of these transformations, the region saw the emergence of various types of social movements questioning the neoliberal models imposed during the previous years, when the majority of countries were led by governments of democratic transition, in the aftermath of the dictatorships of the last decades of the 20th century (Lamadrid Alvarez & Benitt Navarrete 2019: 2).

[8] The pink tide government of Uruguay legalised abortion and same-sex marriage, and recognised the law of gender identity (Friedman and Tabbush 2020: 58)

[9] The comic was included in the exhibition and catalogue ‘Nosotras contamos. Un recorrido por la obra de autoras de comics y humor gráfico de ayer y hoy,’ curated by Mariela Acevedo. The initiative was promoted by various members of Feminismo gráfico, and brought together comic materials by female authors published in different formats between 1930 and 2019 (Acevedo 2020: 6).

[10] ‘How can feminisms today outline strategies of resistance that are not trapped in the neoliberal coordinates in which they are embedded? For this mass feminism, while positioning itself against neoliberalism, finds itself in neoliberalism.’ (2019: 25).

REFERENCES

Acevedo, Mariela (2020), ‘Nosotras contamos. Notas en torno a construir genealogía feminista en el campo de la historieta y el humor gráfico (Argentina, 1933 – 2019),’ Revista Tempo e Argumento, Vol. 12, No. 31, pp. 1-28.

Agamben, Giorgio (2005), State of Exception, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ahmed, Sara (2017), Living a Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University Press.

Alvarez, Silvia Lamadrid & Alexandra Benitt Navarrete (2019), ‘Cronología del movimiento feminista en Chile 2006-2016,’ Revista Estudos Feministas Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 1-15.

Abbate, Florencia (2018), ‘Procesos de subjetivación feminista en las movilizaciones #NiUnaMenos en Argentina,’ Letras Femeninas, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 147-158.

Bacci, Claudia Andrea (2020), ‘Ahora que estamos juntas: memorias, políticas y emociones feministas,’ Revista Estudos Feministas Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 1-15.

Butler, Judith (1990), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York: Routledge.

Ciriza, Alejandra (2018), ‘Tras los pasos de las relaciones entre mujeres e ilustración en tierras nuestro-americanas: Notas para un debate’, in Eduardo Rueda and Susana Villavicencio (eds), Modernidad, Colonialismo y Emancipación En América Latina, Buenos Aires: CLACSO, pp. 59-84.

Espinosa Miñoso, Yuderkys, Diana Gómez Correal & Karina Ochoa Muñoz (2014), ‘Introducción,’ in Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, Diana Gómez Correal & Karina Ochoa Muñoz (eds), Tejiendo de otro modo: Feminismo, epistemología y apuestas descoloniales en Abya Yala, Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca, pp. 13-40.

Friedman, Elisabeth Jay, Felicitas Rossi & Constanza Tabbush (eds.) (2020), Género, sexualidad e izquierdas latinoamericanas: El reclamo de derechos durante la marea rosa, Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Gandolfo, Amadeo & Pablo Turnes (2020), ‘Chicks Attack! Making Feminist Comics in Latin America.’ Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 2-22.

Iribarren, Laura Andrea (2019), ‘Imágenes de la resistencia: Diseño emergente en la lucha por la despenalización del aborto,’ in ACTAS – Jornadas de Investigación, pp. 508-19.

Larrondo, Marina & Camila Ponce Lara (eds.) (2019), Activismos feministas jóvenes: Emergencias, actrices y luchas en América Latina, Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Ministerio de Seguridad (Presidencia de la Nación, Argentina) (2019), Informe de Femicidios, October 2019, http://www.dpn.gob.ar/documentos/Observatorio_Femicidios_-_Informe_Femicidios_2018_-_SSEC_OFDPN.pdf (last accessed 25 August 2022).

Miodrag, Hannah (2013), Comics and Language: Reimagining Critical Discourse on the Form, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Peller, Mariela & Alejandra Oberti (2020), ‘Escribir la violencia hacia las mujeres. Feminismo, afectos y hospitalidad,’ Revista Estudos Feministas Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 1-13.

Poletti, Anna (2016), ‘Periperformative Life Narrative,’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp. 359-79.

Pérez-Rosario, Vanessa (2018), ‘On Beauty and Protest.’ WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 1-2, pp. 279-85.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (2003), Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham: Duke University Press.

Segato, Rita Laura (2014) ‘Colonialidad y patriarcado moderno: expansión del frente estatal, modernización, y la vida de las mujeres,’ in Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, Diana Gómez Correal & Karina Ochoa Muñoz (eds), Tejiendo de otro modo: Feminismo, epistemología y apuestas descoloniales en Abya Yala, Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca, pp. 75-90.

Varela, Jazmín (2018), Tengo unas flores con tu nombre (guía práctica de sororidad), Buenos Aires: Maten al mensajero.

Varela, Jazmín (2018b), ‘Un ramo de dibujos ayuda a entender qué es la sororidad’ Interview by Arlen Buchara. Diario El Ciudadano y la Región (blog), 25 May 2018, https://www.elciudadanoweb.com/un-ramo-de-dibujos-ayuda-a-entender-que-es-la-sororidad/ (last accessed 23 March 2023).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey