Palatable Political Passion Projects? Feminist Instatoons in South Korea

by: Sarah Molisso , March 30, 2023

by: Sarah Molisso , March 30, 2023

Introduction

This article builds on the work of existing English language-printed academic texts on webtoons and webcomics, and introduces instatoons (a portmanteau of Instagram and cartoon) as a medium used by creators to disseminate feminist ideas. Webcomics, as an instrument of feminist storytelling, are seen worldwide. Dubbati (2017) has examined Deena Mohamed’s webcomic Qahera, an Egyptian hijab-wearing superheroine; the French comic artist Emma (2017) published a series of comics in The Guardian, depicting issues such as ‘the mental load’ and maternity leave; Canadian artist Aminder Dhaliwal’s (2017) Instagram series Woman World tells a story of a post-apocalyptic future where men are extinct; and the Indian webcomic Priya Shakti (2014) follows a rape survivor ‘who, along with the Goddess Parvati, defends women against sexual predators’ (Aldama 2021: 5). Focusing on two South Korean (hereafter Korean) instatoons by the award-winning creator Soo Shin Ji (수신지), the notion of Korean feminist instatoons as palatable political passions projects will be explored. Myeoneuragi (며느라기, also known as SARIN) (2017-2018), and Gone (곤) (2019-2020), were both initially published on Instagram and Facebook. Myeoneuragi follows newlywed Min Sa-rin, tracking her experiences of day-to-day inequalities during her incorporation into her husband’s family, and Gone is set in a fictional world where all women who have had abortions face legal punishments.

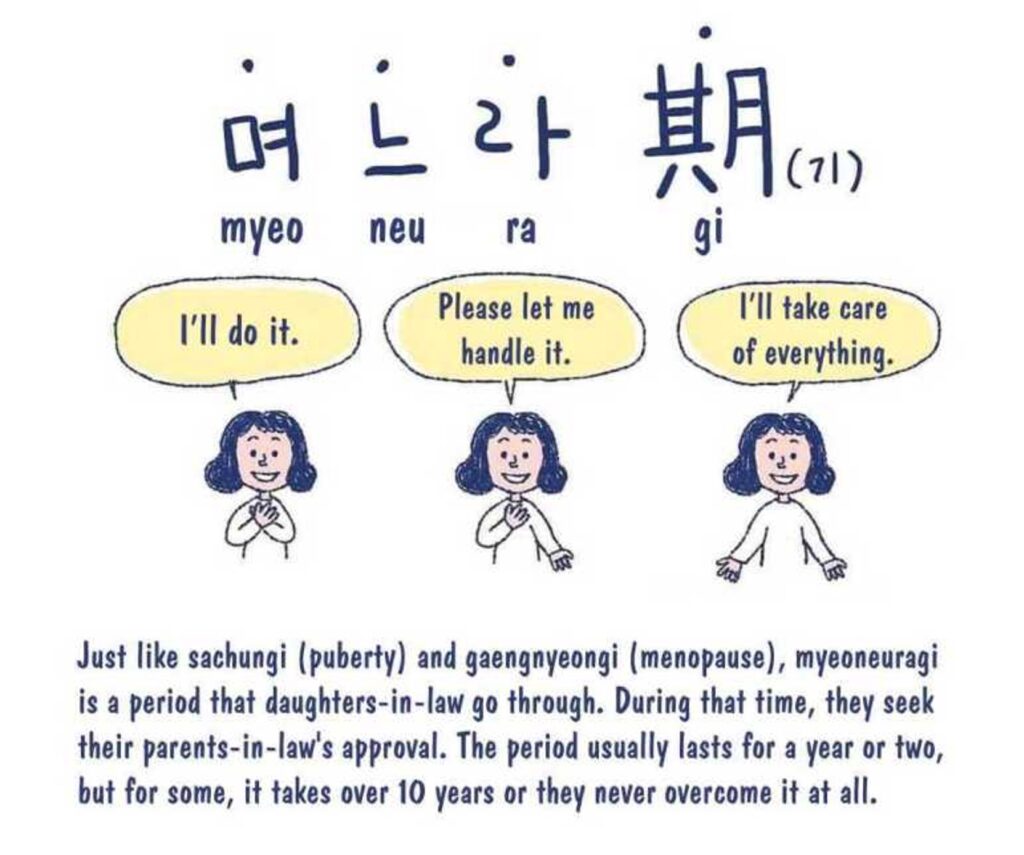

Myeoneuragi, begins with the wedding of the main character Min Sa-rin and her husband Mu Gu-young. The instatoon quickly shows the subtle inequalities that Sa-rin experiences on a daily basis, while she navigates her company job and her new role as a daughter-in-law (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Explanation of the meaning of Myeoneuragi, screenshot taken on 24th August 2020.

Soo Shin Ji has said that ‘as I went along and saw how people reacted to the episodes, I realised that it was a bigger problem than I had thought. I myself in the past hadn’t been aware of issues [regarding sexist discrimination], but I learned through people’s comments and reactions that it was anything but small’ (Yoon 2019).

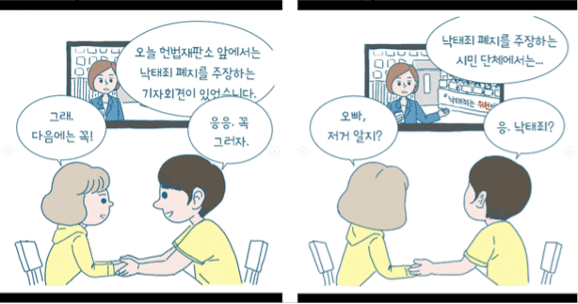

Following the transmedia success of Myeoneuragi, which was acquired by Kakao Webtoon and developed into a streaming television series No, Thank You (2020-), Soo Shin Ji released the instatoon Gone. Gone is set in a dystopian parallel world where the Constitutional Court has ruled that anyone who has had an abortion at least once since 1953 (when abortion was criminalised) will face criminal punishment. This is determined through an Induced Abortion Test (referred to as an IAT), and all women with Korean nationality who were born after 1939 must undergo the IAT. This instatoon has also been obtained by Kakao Webtoon (both webtoons now require a monetary subscription in order to read past certain episodes), although some of the original episodes can still be found on the Instagram page, @noh.family. The early episodes of this instatoon show the innocuous way in which the change in ruling is disseminated to everyday people (fig. 2) and follows the daily lives of three siblings, Noh Min-hyeong, Noh Min-a, and Noh Min-tae. Min-hyeong is a working mother who entrusts the care of her son to her mother, Min-a worries about her career due to an unplanned pregnancy, and Min-tae navigates his relationship with his recently pregnant girlfriend Na Saet-byeol and tries to find somewhere that can perform an illegal abortion (Lee 2020). Over the course of the series their mother receives a positive IAT test after having had an abortion at a public health centre in the past, yet while she is criminalised, the father avoids any punishment. The instatoon reflects the double standards of society regarding abortion and gender discrimination generally.

Both of Soo Shin Ji’s instatoons discuss gender inequalities in Korea through subtle critiques and simple, everyday storytelling with relatable characters. Married women relate to Sa-rin’s situation, and along with Gone, both instatoons provide a reflection on modern society and the injustices, however big or small, that women face.

Korean feminist instatoons can be characterised in three ways: they are palatable, political, and creator- and audience-driven ‘passion projects.’ Korean feminist instatoons engage in a form of palatable feminism; that is, Soo Shin Ji’s instatoons Myeoneuragi and Gone are palatable: they are basic, and easily digestible for readers new to the idea of critiquing their everyday lives and locating it in feminist discourse. Korean feminist instatoons are ‘political projects,’ in the same way that the aforementioned webcomics are. For example, Qahera was created ‘in response to media representation of Muslim women and Egyptian women’s living conditions post-Arab Spring’ (Dubbati, 2017: 438). Nagtegaal (2021) has highlighted Quan Zhou’s contributions to using webcomics as a pathway to fight for gender and racial equality, ‘much of… [which] can be said to participate in the so-called fourth-wave feminist movement’ (Nagtegaal, 2021: 143). Quan Zhou also lends their voice to contest traditional patriarchal tropes and pressures for Chinese women to marry in a similar way to Soo Shin Ji’s social commentary. Finally, instatoons (not Korea-specific) are creator (and consumer) driven ‘passion projects.’ Similar to Korean webtoons’ transmedia capabilities, it is possible for instatoons to transcend their place of origin and gain financial and cultural traction, as Myeoneuragi has done. This article will address each of these notions in turn. Firstly, a (re)definition of palatable feminism will be given and discussed in relation to Soo Shin Ji’s two instatoons. Secondly, to understand the nature of Korean feminist instatoons as a political act, the themes of Myeoneuragi and Gone will be looked at in connection with the current feminist discourse in Korea. Thirdly, the idea of instatoons as ‘passion projects’ will examine Instagram as a platform for webcomics and webtoons.

Palatable Feminism

Instatoons have emerged as a palatable interpretation of feminism (similar to hashtag activism seen in the past, see Kim (2017)), and is one that can both subtly critique gender norms and reach a wider audience in a society in which feminism is a dirty word. The meaning here of my use of the phrase palatable feminism is different from the negative connotations of its previous uses:

I think the student who asked about ‘making feminism palatable’ has a rather bizarre view of what feminism is—as if she/he wants to transform ‘pack, refuel and reload’ into ‘cleanse, tone and moisturise?’—which is awful in a million, million different ways. Making feminism palatable. This has so much to do with ‘rebranding’ masculinity and femininity… In the journey(s) from/to thought/concept/passion, to/from institutionalisation, feminism has undergone a governance makeover, and as a consequence feminism has become palatable for contemporary use, perhaps explaining its mainstream acceptance and even its cultural appeal (Barbarachild et al 2013: 35-70).

The difference of my use of palatable feminism here is that in Korea, feminism is not accepted in the mainstream, and is only culturally appealing to a niche audience. Instead, palatable feminism is one that has been stripped back, omitting more complex discourses and notions of intersectional feminisms. Palatable feminism has the ability to speak to the masses: in the Anglo-American sphere, this would speak to White cis-hetero women; within Myeoneuragi and Gone it speaks to Korean cis-hetero women. Globally, 47% of women identify as feminists (based on a survey of 30 countries with participants aged 16-74) (Ipsos 2022). 48% define themselves as feminist in Great Britain, but only 24% of women surveyed between the ages of 16-74 identify as feminist in Korea. Moreover, Korea had the highest ‘% disagree somewhat/ strongly’ to the statement I define myself as a feminist at 75% (among men and women, compared to a global country average of 48%) (Ipsos 2022). These results show that there is not a mainstream acceptance or cultural appeal of feminism when considering if individuals identify as a feminist.

Gill (2016) has spoken of ‘the cool-ing of feminism’ (2016: 618) to describe the widespread popularity of celebrity and style feminism in the UK (the white, Western, middle-class, cis-hetero, youthful UK), and building on this, Banet-Weiser, Gill & Rottenberg (2020) have argued (tentatively) that ‘neoliberal feminism, with its constitutive notion of a happy work-family balance, has helped to render feminism palatable and legitimate, which has, in turn, facilitated feminism’s widespread diffusion, embrace and circulation within the Anglo-American mainstream cultural landscape’ (2020: 8). Instead of situating palatable feminism within the frame of a happy work-family balance, the instatoons Myeoneuragi and Gone reject neoliberal feminism and frame feminist issues ‘to other inequalities or located in the broader context of neoliberal capitalism’ (2016: 615-616). My use of palatable feminism is more akin to Jackson’s (2021) research on basic feminism:

celebrity feminists represented [basic feminism] whereas a more implicit construction of ‘deep’ feminism signalled an educated, political, and intersectional feminism. However, girls [the research participants] did not apply the term ‘basic’ (or its counterparts ‘surface,’ ‘easy,’ ‘shallow’) in an inherently negative way but rather located it on a continuum where it represented a start point toward a ‘deeper,’ more meaningful feminism (Jackson 2021: 1079).

Korean feminist instatoons are similarly located on a continuum, acting as a start point for audiences who read them, who may not have previously been actively involved in feminist movements. Because of the subtle critiques of society, and the subtle exposure of misogyny in a patriarchal society, Soo Shin Ji’s instatoons are palatable, basic, and easily digestible. Soo Shin Ji has said of Myeoneuragi, ‘the reason I chose to talk about it through a cartoon is because it’s an analogue form of content that you can enjoy on a digital device. People get to choose how much time they will spend looking at a cut of the cartoon. And when they do spend time and linger on a certain line or a scene, then it begins to sink in—it may not become an immediate remedy, but it provides room for thought’ (Yoon 2019).

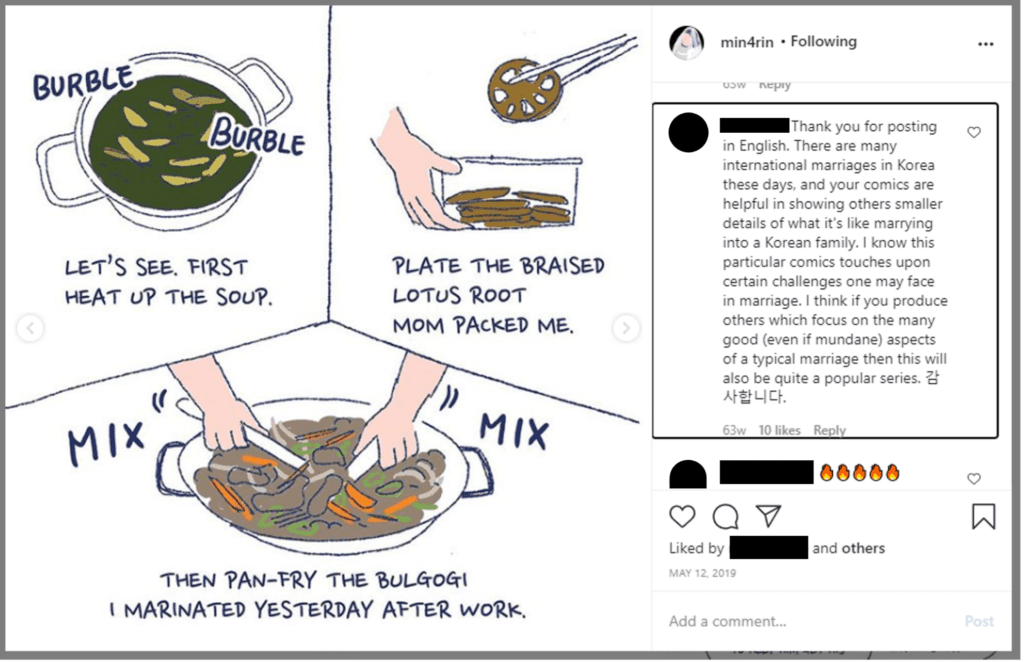

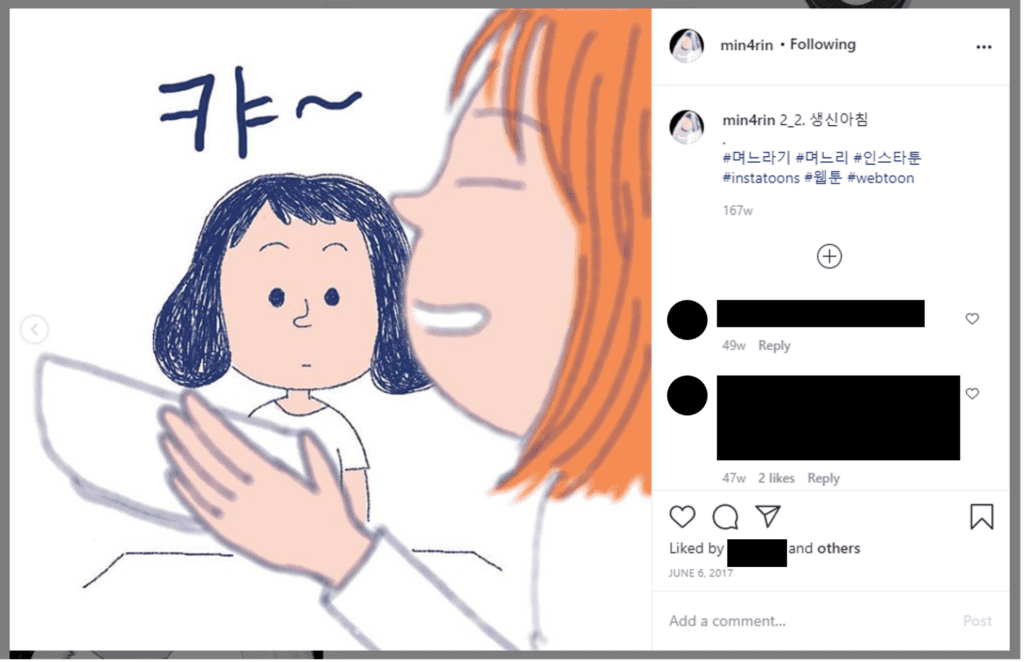

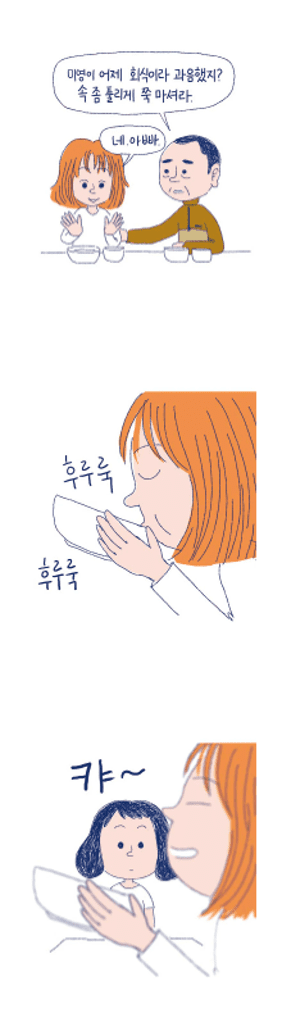

The first episode of Myeoneuragi, posted on 23rd May 2017 (now deleted from Instagram) sets the scene with Min Sa-rin at work being bombarded with messages from her new sister-in-law asking her to make seaweed soup for her mother-in-law’s birthday (a dish traditionally eaten on birthdays in Korea). Upon arriving at her in-laws’ the night before in order to get up early to cook breakfast, Sa-rin tries to act in an appeasing way, although is clearly uncomfortable. Fig. 3 shows a screenshot of part of Episode 2 of the English version. Here, we see Sa-rin preparing breakfast. The comment (anonymised) shows the transnational appeal of Myeoneuragi:

Thank you for posting in English. There are many international marriages in Korea these days, and your comics are helpful in showing others smaller details of what it’s like marrying into a Korean family. I know this particular comic touches upon certain challenges one may face in marriage

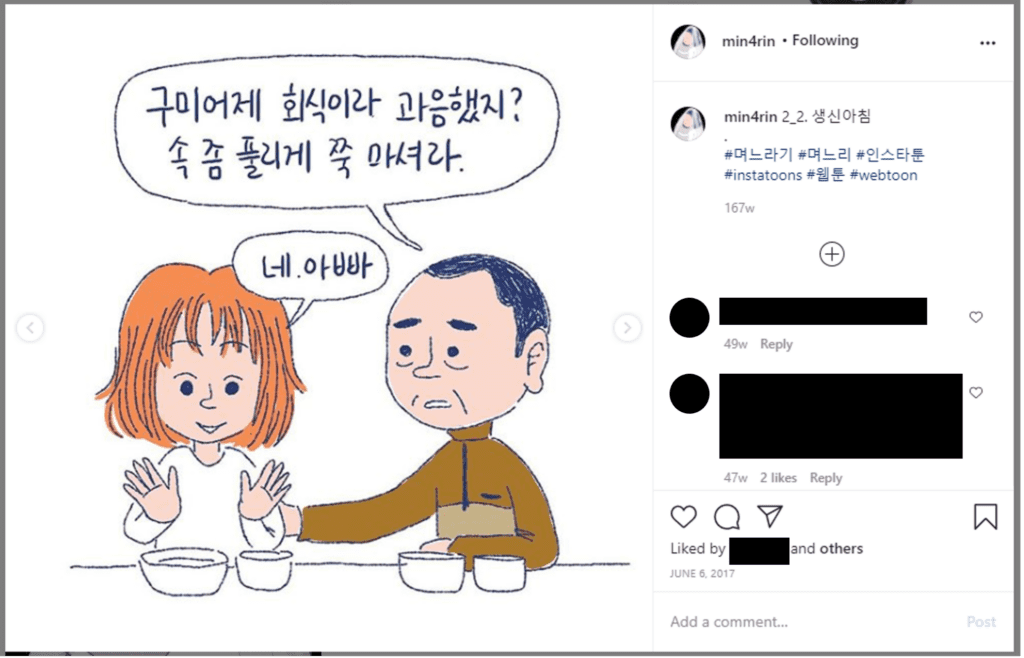

The subtle critique here is that we later find out that Sa-rin’s sister-in-law is hungover from going out the night before with her company. Her father tells her to drink her soup until she feels better, while Sa-rin watches on (fig. 4 and fig. 5). Sa-rin alone has prepared breakfast for her mother-in-law, her husband apologises for not helping, and Sa-rin is visibly annoyed. This experience is clearly not one felt solely by Korean brides, but also brides of transnational marriages, too.

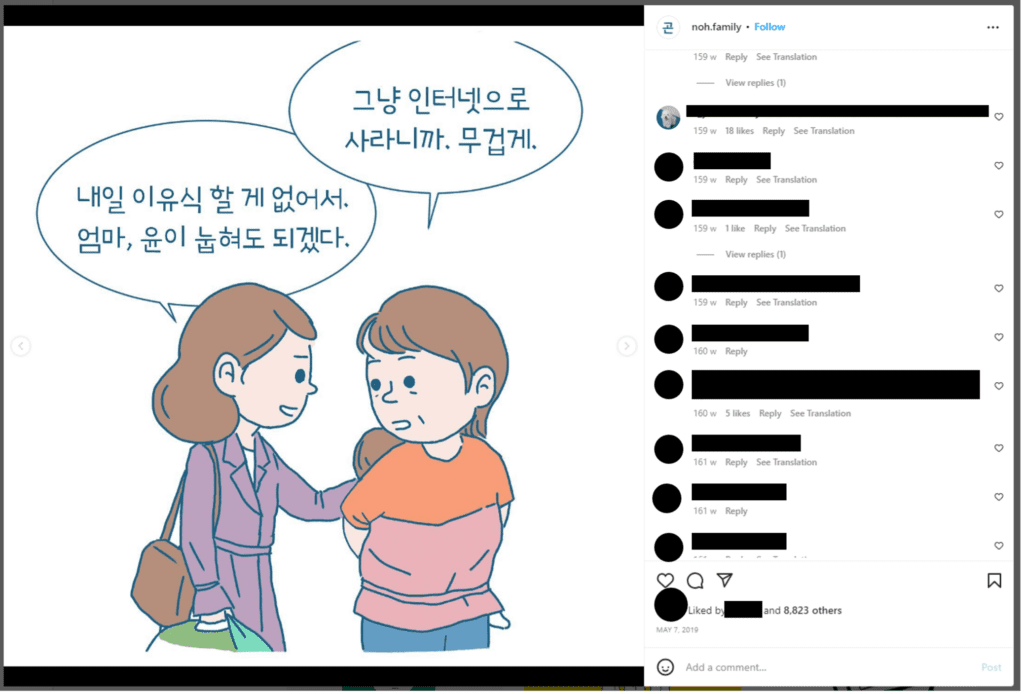

In one of the first scenes of Gone (fig. 6), Noh Min-hyeong and her mother—who looks after her child during the day while she is at work—are chatting after Min-hyeong returns home. This scene shows the gendered domestic work of women who have to juggle work with motherhood, as well as the lack of childcare in Korea for working mothers and dependency on informal childcare. Some of the comments (hidden for anonymity and translated from Korean) read:

‘What are the husband, father-in-law and father doing? ^^ :(.’

***

‘Wow, these are conversations that men wouldn’t even think about.’

***

‘This is me and my mom right now… My tears are running.’

***

‘When I first saw this, I thought it was a single mother’s family :(‘

It appears here that there is a connection between the characters’ situations and the readers of Gone. Where men are allowed to pursue their careers unhindered, it falls to women (wives, grandmothers, aunts, sisters, etc.) to juggle both their careers and family care. The stories depicted in Myeoneuragi and Gone do not require great leaps of the imagination, and they engage in subtle critiques of systemic factors that lead to, or maintain, gender inequality. Instead of focusing on more heavy topics, like gender-based violence (a common occurrence in Korea: Kim (2020) has highlighted the shocking statistic that at least one woman was killed or seriously injured by her male partner every 1.8 days in 2019), Soo Shin Ji’s instatoons have addressed issues that speak to the masses. These issues have been repackaged in a way that makes them palatable, and easily consumable for its audience.

Feminist Instatoons as Political Acts

Myeoneuragi and Gone highlight some of the gender inequalities that exist in Korea today, from traditional expectations of marriage, to working mothers, and domestic and reproductive burdens being women’s issues. Korea ranked 102 out of 156 countries in the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum 2021) due to its low scores in political empowerment and economic participation and opportunity. After the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (also known as the IMF crisis), South Korea’s GDP dropped dramatically in 1998, and women bore the brunt of the employment losses that were to follow (Ma 2014). Women workers were dismissed more quickly than their male counterparts, with pregnant women being the first to be laid off, followed by married women. Due to this, some women postponed reporting their marriage or tried to keep up the appearance of being single and were dubbed IMF cheonyeo (IMF maidens) (Cho 2012).

The after-effects of the financial crisis spelled chaos for women workers: they were relegated to part-time, temporary, and outsourced employment (Cho 2008). Falling birth-rates, along with an increased divorce rate and an increase in the number of unmarried women, were attributed to women’s selfish choices (Nelson & Cho 2016). These issues were rarely linked to women’s unemployment issues and were nicknamed birth strikes and marriage sabotages (Cho 2012). This negative link between marriage (or lack-of) and precarious work is echoed in Gone and Myeoneuragi, where at times Sa-rin’s work is not considered as important as Gu-young’s.

Alongside this negative view of women, new forms of femininity emerged in the early and mid-2000s as a direct result of the IMF Crisis, and Korea’s emerging new neoliberal identity. Starbucks opened its first shop in Korea in 1999, and the consumption of its coffee was seen as an ‘aspirational act of consumerism’ (Song 2014: 430), linked to class and gender differences. Song’s study shows how women navigate Starbucks as a way to subvert gender norms which Song argues are ‘defined by the codes of Confucian patriarchy’ (2014: 431), the coffeehouse provides women with a third place that exists outside of the family and ‘dominant systems of patriarchy’ (2014: 435).

For women, Starbucks was a space that signified privilege, linked to Western lifestyles; but to men, Starbucks was too frivolous and leisurely, and took time and money away from Korean products. The backlash was most strongly targeted towards the female middle-class consumer, branded as soybean paste girl (doenjang nyeo) (the implication being that she only ate soybean-paste stew, a cheap meal, in order to be able to show her high purchasing power at Starbucks). These soybean paste girls were materialistic, obsessed with Western luxury goods, and were criticised for supposedly using men to buy these goods (Song 2014). These qualities existed in direct opposition to the ideal virtuous woman (the wise mother, good wife trope (Choi 2009)), traditionally desired for marriage. The idea of soybean paste girls proliferated as online comics, which showed the tensions in South Korea between ‘class, gender, and national identity’ (Song 2014: 444).

President Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) was a supporter of neo-developmentalism: pro-natal policies were thrown into the mainstream to achieve economic development, with Lee allocating large budgets to several policies which Hur (2013) argues were not representative of women’s voices or their experiences. Women were reduced to their reproductive capabilities based on heteronormative family systems. Lee’s government announced it would enforce existing laws and crack down on illegal abortions in 2010 (Kim & Bae, 2018) (eventually legalised in 2019) to combat the chronic low fertility rate that the country was experiencing. [1] From the beginning of Lee’s presidency, gender equality was tied to the idea of work and family policy (Ma, Kim & Lee 2016). Lee’s government focused less on childcare provisions in bringing women into economic participation, and more on ‘career discontinuity, family friendly businesses, and flexible working arrangements’ (Ma, Kim and Lee 2016: 634), thereby placing the responsibility of both childcare and work on women.

2015 saw a new wave of feminist activism, which has been coined the feminism reboot (see Sohn 2017). The rise in misogynistic discourse since the 2010s has mainly targeted young women (Kim 2021), including slurs such as: kimchi girl (similar to soybean paste girl which shows disdain towards women’s independence and autonomy), sam il han (meaning a woman should be beaten every three days), sang pye nyeo (disparaging old women or those with no sexual appeal), and me gal chung (comparing the users of the radical feminist website, Megalia, to a pest) (Ahn et al 2016; Kim 2018). The website Megalia (2015-2016) was created concurrently with other online acts of feminist activism. Megalia sought to expose accepted misogynistic language through mirroring: instead of kimchi girl, kimchi man ridiculed men’s excessive purchasing of sex (Y Kim 2021) and mocked their ‘6.9cm penises’ (Oh 2021). A splinter site, Womad, was established in 2016 which is more shocking in content, and more closely aligned to raet pem, self-identified radical feminists.

Along with the creation of Megalia, hashtag activism started to gain traction. The hashtag #IAmAFeminist was the ‘first public and collective cry of those who identify as feminists’ (Kim 2017: 805). This hashtag simultaneously mobilised existing self-identified feminists, as well as introducing a chance for others to identify as one too. The hashtag was used in conjunction with a variety of issues, such as ancestral rites, sex-selective abortion, domestic work, gender pay gaps—amongst others—making feminist issues and women’s rights more relatable to a broader audience. The hashtag #IAmAFeminist enabled a wide range of people to share similar concerns and ideas, consequently lowering the barriers of feminist identification. Other hashtags highlighting issues of sexual violence have occurred, including #sexual_abuse/violence_in_000, #MeToo, #WithYou (showing support for the victims), and #ISurvived (in response to the 2016 murder of a 23-year-old woman in a public toilet near Gangnam station to report everyday gender-based violence). Another type of feminist activism is sticky note activism—the use of post-it notes as a tool to disseminate feminist ideas—which originated in Megalia’s 2015 Post-it Project and was also used in response to the Gangnam murder. Post-it notes are independent, personal, easy to use, universally available, and easy to remove in order to clean a space (placing less of a burden on cleaners, who tend to be women) (Kim 2021).

The largest women’s rally against male violence seen in Korea, also known as the Hyehwa Station demonstrations, took place in 2018 in response to the double standards of police response to perpetrators of image-based sexual abuse. By December 2018 after six rallies, 350,000 accumulated participants had taken part in these women-only protests (Park 2020). The protests spawned the infamous slogan My Life is Not Your Porn along with other feminist acts of solidarity. The feminist faction Tal Corset (Escape the Corset) performed acts of head-shaving, along with delivering speeches on the corset and male violence (Park 2020). Tal Corset rejects the notion of femininity, arguing that ‘beauty practices are a marker of women’s inferior social status [and that] women … seek to be respected as humans, not sexual objects’ (Park 2020).

Similar feminist movements include 4B (4-Nos), who address existing feminist groups’ inaction in addressing the precarity faced by young women. The 4B movement refuses to engage in traditional patriarchal relationships: heterosexual marriage, childbirth, romance, and sexual acts (Lee & Jeong 2021: 637). As of 2019, 48.9% of Korean women in their 20s identify as feminists, yet almost 80% recognise the seriousness of gender stereotypes and discrimination against women; there is also a high level of support among women for the #MeToo movement (88.8%), the Tal Corset movement (56.3%), and the Hyehwa station demonstrations (60.6%) (Korean Women’s Development Institute 2019). There appears to be a dissonance between feminist issues, feminist movements, and feminist identity.

As part of my PhD research, I conducted a survey through Qualtrics, gaining 521 responses. In response to the question asking participants if they thought Myeoneuragi was a feminist webtoon/instatoon and why, responses highlighted the widespread and universal feeling of gender inequalities and patriarchal systems, including the realities of marriage, conservatism, and traditional rites:

‘It depicts real struggles that many women face in Korean society’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘It describes how your life can change just because you are a woman who decided to get married in Korean culture. It resonated with my own experience a lot as well. To improve a situation like this individual stories have to be shared because there are people who simply do not know that this type of issues exist [sic.]. Even though this webtoon does not talk about how to solve issues or what to do differently proactively, I think it is a very good feminism material because it shares stories of people who were suffering quietly without realising that it is a social problem. They might have been internalising these issues like ‘I am not bold enough to say whatever I want to say to my inlaws, it is my personality.’ or ‘I am being too sensitive.’ etc etc.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘In my opinion, the webtoon well describes the reality of Korean wedding and marriage culture. Very unfair for female and patriarchy.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘It describes about married Korean woman’s life and Korean culture especially patriarchy and 제사 [ancestral rites]. It’s quite hilarious that so many old Korean regards 제사 as their important thing but don’t do that themselves and force to do to daughter in law (who is totally from other familly and don’t have any blood heritage about their family [sic.].)’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘Korea is a very conservative country where more modern ways of life are still struggling. The old generation does not even try to understand the youth and imposes only its own opinion. Of course, traditions are traditions, but in the 21st century everything is arranged in a new way and it is tedious to learn according to new foundations. 며느라기 [Myeoneuragi] does not want her family to be conservative and tries to achieve equality in the family … but unfortunately her husband is satisfied with the traditional foundations, where a woman is a slave of her family and husband.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘It shows the absurdity of the patriarchal system prevalent in Korea, and as a reader, it gives room to think about how to improve the problem.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘It’s a simple and uncomfortable situation that was hard to express in words.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘The author easily tells stories that any woman living in Korea can relate to through cartoons. Readers sometimes sympathize, sometimes angry, and criticize the contradictions of those who belong to the patriarchy. I think it is a work that reveals perhaps the most honest feminism by calmly portraying the part where the main character is discriminated and alienated just because she is a woman.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

***

‘Feminism considers women’s lives, which were considered personal, to include revealing that they are not individual problems, but universal and structural.’ (Anonymous Respondent)

The storylines in Myeoneuragi and Gone show the lingering pressures on working women and the aftereffects of neo-developmental policies. Bringing these issues into the online sphere through a widely accessed social networking service. [2] Whereas feminist websites such as Megalia and Womad anonymise the user, Instagram is directly related to the user in that their account will (usually) have pictures of themselves, their lives, and their locations, all available for public access. This differs slightly from Twitter which, while also personal, has a level of intimacy removed. Associating your image to a positive comment on an instatoon is a radical, political act in a society where victims of online crimes are plenty. The backlash that someone could face for publicly aligning with feminist discourse could include misogynistic abuse and threats, doxxing, and other forms of harassment within the framework of toxic technocultures (Filipovic 2007; Oh 2021).

‘Passion Projects’

Cho (2021) has argued that Korean webtoon creation shows the ongoing and growing reliance on webtoons platforms, in what Cho has dubbed ‘the platformisation of culture’ (2021: 75). Within these platforms a three-tier competition has usually operated, promoting competition to reach the top-tier through positive feedback and ratings (Kim & Yu 2019). Pyo, Jang and Yoon (2020) focus on three core agents in webtoon production: webtoon creators (the artists), producers (recruiter and managers of creators), and platform companies. While professional webtoon creators have to navigate highly competitive webtoon platforms to gain any traction (utilising ‘competition crowdsourcing’ (Kim & Yu, 2019)), Instagram can serve as a cheap, accessible medium to challenge normative gender roles and identities. Since February 2017, when Instagram first let users upload more than ten pictures per post, the platform has become a perfect platform on which to read short comics. Instead of scrolling vertically, as is characteristic of webtoons, readers can ‘swipe through the gallery’ (Van 2020), that is, they can scroll horizontally between panels of the instatoon. Instagram’s gallery feature enables readership to be controlled by the creator, to a certain extent, as it helps to ‘maintain narrative coherence within each episode’ (Tréhondart 2020). Therefore, creating instatoons can be seen as a labour of love, as a passion project for the artists who act simultaneously as the creators, producers, and managers of their Instagram accounts.

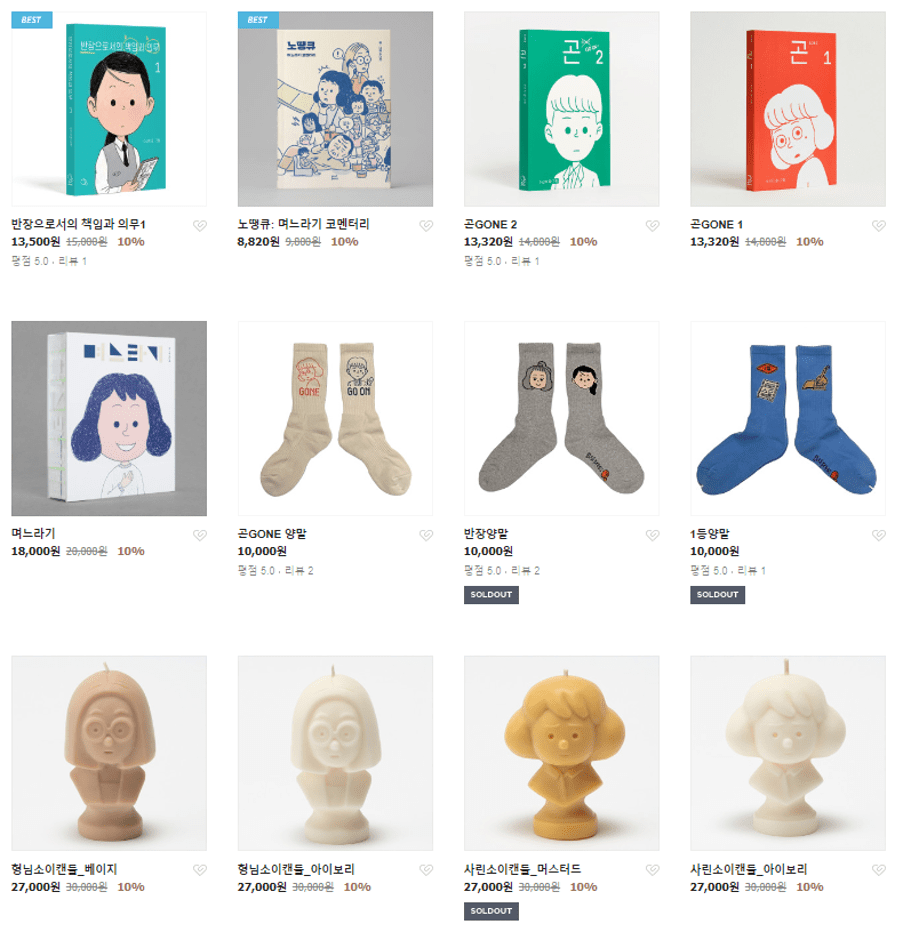

The idea of instatoons as creator passion projects can also be seen in their transnational capabilities. Generally, webtoons on webtoon platforms benefit from the contributions of fan translators, also known as ‘transcreators,’ who are vital in promoting the global spread of webtoons (Yecies et al 2020; Nam and Jung 2022). By contrast, the early English translations of Myeoneuragi on Instagram were also posted by @min4rin instead of a separate fan base, although as noted earlier on these translations were greatly welcomed by the readers. In the move to Kakao Webtoon, these were deleted from Instagram along with much of the Korean version. On the other hand, Gone has been translated into Japanese and is available to buy as a book, which is advertised on @no.family. Myeoneuragi is available to buy in Mandarin, and both Myeoneuragi and Gone are available in Korean. These are advertised on Soo Shin Ji’s Instagram page, @sooshinji. A whole host of merchandise is also available to buy, including books, socks, and candles (fig. 7).

Myeoneuragi displays elements of transmedia and transnational crossovers found in other webtoons. No, Thank You (2020-2022) is the Kakao TV series based on Myeoneuragi, which was the first Kakao TV drama to place in the top 10 most popular dramas list on the streaming platform, Wavve (Lim 2021). To date there have been two series, each consisting of twelve 20-minute episodes. Of course, Kakao’s acquisition has transformed Myeoneuragi from an instatoon to a webtoon. In doing so, the act of reading Myeoneuragi has reverted to the traditional webtoon format: scrolling vertically down a screen instead of horizontally between panels (fig. 8). As mentioned previously, the original posts of the instatoon were deleted, which also deleted all of the reader engagement: friends who had been tagged, likes, and comments. The Kakao Webtoon page has its own comments section, where comments can be liked, disliked, or replied to. However, I believe the essence of Myeoneuragi as a political feminist instatoon has been dampened here; you need a Kakao Webtoon account to interact with other readers—in other words, you need to already be reading webtoons to read this one as well.

Conclusion

‘Through Instagram, comic artists can share their ideas, express their ideas, and influence public opinion’ (Audinovic and Nugroho, 2021: 296), and politicised virtual spaces for women that are comfortable and familiar are critical for producing and maintaining online feminist communities (Choi, Steiner & Kim 2006). Instatoons are similar to other movements on social media, specifically hashtag activism in the way that they can introduce feminism in a non-confrontational way, and potentially bridge the gap between feminist issues, movements, and identity. Hashtag activism has introduced feminism to an audience that was not necessarily seeking feminist content, and has helped to move feminism into a public space where issues are tangibly related to the author of the content found under the hashtags. Similar to sticky note activism, Instatoons are created by individuals, but they are tangible products that can be ‘picked up’ and distributed among friends and peers. Instatoons also transcend these social media movements in that they have transmedia capabilities. What started as a passion project has developed into a television series, become a printed text, and has been translated into other languages. In the same way that post-it notes can be seen anywhere by anyone, the books and the television series that came from Myeoneuragi have widened its reach even further than was possible on Instagram.

However, it is important to recognise that even though these introductory feminist mediums have the ability to stimulate discussion on everyday misogynistic practices, neither of the instatoons Myeoneuragi or Gone explore the stories of any marginalised groups. Emergent feminist visibilities on Instagram are just as curated as on other social media platforms, with some ‘feminist viewpoints … more effortlessly reconcilable with Instagram’s interaction order’ (Savolainen, Uitermark & Boy 2020: 559). The palatability of Myeoneuragi and Gone as a softly-softly approach to disseminating feminist ideas has a wide reach, but a superficial one nonetheless. Focusing on issues within traditional marriage systems and double standards towards men and women omits a large and vast number of problems and does not take into account other intersectional issues.

The narratives of the everyday woman/ family as seen in Myeoneuragi and Gone exclude issues of class/ economic disparity (Korea’s economic inequality has seen a large polarisation since the IMF crisis; a ‘widening gap between the top income group and the rest of the population … [and] growing income disparity occurring in the labour market, between regular and non-regular workers and between employees of large firms and of medium-to-smaller firms’ (Koo 2021)), migrant workers, who occupy most of the 3D industry: dirty, dangerous, and demeaning jobs (Denney 2015), and LGBTQI+ communities, among others, as well as addressing the White neo-colonial discourses that shape much of the back-and-forth between extremist groups (Oh 2021). These include Megalia’s mockery of 6.9 cm penises, which is steeped in racism about Asian men’s emasculation (Oh 2021). Similarly, Womad’s exclusionary practices towards transwomen were even seen at the Hyehwa Station demonstrations, which transwomen were actively discouraged from joining.

When viewing feminist instatoons as a palatable medium, perhaps surface-level feminism is all that they are capable of, and all that they should be capable of. In acting as a vessel to introduce feminist discourse in the basic form of gender inequality, double standards, and misogynist practice, Myeoneuragi and Gone represent an exciting and growing medium that is being created by passionate artists, activists, and storytellers, in their attempts to introduce feminist ideas to wider audiences.

Notes

[1] As of 2022, Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world (Kim 2022).

[2] Of the 521 survey responses, 392 participants reportedly use Instagram, which is almost triple the number of those that use the second and third most popular services, Twitter (138) and Daum Café (137).

REFERENCES

Ahn, Sang Su, In Soon Kim, Jung Hyun Lee & Bo Ra Yun (2016), ‘Basic Research on Korean Men’s Life (II): Focus on the conflict in values of young men concerning gender equality,’ Korean Women’s Development Institute, 1 May 2016, https://eng.kwdi.re.kr/publications/researchReportDetail.do?page=1&idx=101144 (last accessed 25 August 2022).

Aldama, Frederick Luis (2021), ‘Gender and Sexuality in Comics: The Told, Untold Stories,’ in Frederick Luis Aldama (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Gender and Sexuality in Comic Book Studies, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 1-12.

Audinovic, Vizcardine and Rio Satria Nugroho (2021), ‘Comics as Social Media Criticism of Community Activities Restrictions Enforcement Due to COVID-19 in Indonesia,’ Muharrik: Jurnal Dakwah dan Sosial, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 295-313.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill & Catherine Rottenberg (2020), ‘Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation,’ Feminist Theory, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 3-24.

Barbarachild, Zephyrine, Pip Buckingham, Heather May Morgan & Marysia Zalewski (2013), ‘Making Feminism Palatable,’ in Marysia Zalewski (ed.), Feminist International Relations: Exquisite Corpse, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 33-40.

Cho, Heekyoung (2021), ‘The Platformization of Culture: Webtoon Platforms and Media Ecology in Korea and Beyond,’ The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 73-93.

Cho, Sung-Nam (2008), ‘Globalisation and Women in South Korea: Labor Participation and Women’s Identity,’ in Yunshik Chang, Hyun-ho Seok & Donald Baker (eds), Korea Confronts Globalisation, London: Routledge, pp. 43-62.

Cho, Uhn (2012), ‘Gender inequality and patriarchal order recontexualized,’ in Hee-Yeon Cho, Lawrence Surendra & Hyo-Je Cho (eds), Contemporary South Korean Society: A Critical Perspective, London: Routledge, pp. 18-27.

Choi, Hyaeweol (2009), ‘‘Wise Mother, Good Wife’: A Transcultural Discursive Construct in Modern Korea,’ The Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 1-33.

Choi, Yisook, Linda Steiner & Sooah Kim (2006), ‘Claiming Feminist Space in Korean Cyberterritory,’ Javnost – The Public, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 65-83.

Denney, Steven (2015), ‘South Korea’s Migrant Workers in the Public Eye,’ The Diplomat, 10 September 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/09/south-koreas-migrant-workers-in-the-public-eye/ (last accessed 25 August 2022).

Dubbati, Barkuzar (2017), ‘The Woman in Hijab as a Freak: Super(Muslim)woman in Deena Mohamed’s Webcomic Qahera,’ Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 433-449.

Emma (2017), ‘The gender wars of household chores: a feminist comic,’ The Guardian, 26 May 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/26/gender-wars-household-chores-comic (last accessed 24 August 2022).

Gill, Rosalind (2016), ‘Post-Postfeminism?: New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times,’ Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 610-630.

Hur, Songwoo (2013), ‘Expanding the Feminist Politics of Reproduction in the Context of the Developmental Hegemony of South Korea,’ Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 116-148.

Ipsos (2022), ‘International Women’s Day 2022,’ Ipsos, March 2022, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2022-03/Ipsos%20-%20International%20Women%27s%20Day%202022%20-%20Equality%20Work%20Careers_0.pdf (last accessed 26 August 2022).

Jackson, Sue (2021), ‘‘A Very Basic View of Feminism’: Feminist Girls and Meanings Of (Celebrity) Feminism,’ Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 1072-1090.

Kim, Arin (2020), ‘Most Victims of Dating Violence in Korea are Women: Police,’ Korea Herald, 29 June 2020, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200629000695 (last accessed 24 August 2022).

Kim, Jinsook (2017), ‘#iamafeminist as the ‘Mother Tag’: Feminist Identification and Activism Against Misogyny on Twitter in South Korea”, Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 804-820.

Kim, Jinsook (2018), ‘Misogyny for Male Solidarity: Online Hate Discourse Against Women in South Korea,’ in Jacqueline Ryan Vickery & Tracy Everbach (eds), Mediating Misogyny, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 151-170.

Kim, Jinsook (2021), ‘The Resurgence and Popularization of Feminism in South Korea: Key Issues and Challenges for Contemporary Feminist Activism,’ Korea Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4, pp. 75-101.

Kim, Sam (2022), ‘Korea Shatters Its Own Record for World’s Lowest Fertility Rate,’ BloombergUK, 24 August 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-24/fastest-aging-wealthy-economy-breaks-own-fertility-record-again (last accessed 25 August 2022).

Kim, Youngmi (2021), ‘Mirroring Misogyny in Hell Chosŏn: Megalia, Womad, and Korea’s Feminism in the Age of Digital Populism,’ European Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 101-134.

Kim, Hyosin & Hyun-A Bae (2018), ‘A Critical Assessment of Abortion Law and its Implementation in South Korea,’ Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 71-87.

Kim, Ji-Hyeon & Jun Yu (2019), ‘Platformizing Webtoons: The Impact on Creative and Digital Labor in South Korea,’ Social Media + Society, Vol. 5, No. 4.

Korean Women’s Development Institute (2019), ‘A Survey of 20-Year-Olds’ Perceptions of Feminism in Korean Society,’ Korean Women’s Development Institute, 8 March 2019, https://eng.kwdi.re.kr/publications/cardDetail.do?page=1&idx=102201 (last accessed 26 August 2022)

Lee, Shinji (2020) ‘[Heopeu inteobyu] Weptun ‘myeoneuragi’ husokjak ‘gon’ SooShinJi jakga-neun ‘naktaehan yeoseong-i modu cheobeolban-neun sesang-eul baranya’ go munneunda’ ([Huff Interview] The author of the sequel to Myeoneuragi, Gone, asks ‘Do you want to live in a world where all women who have had an abortion are punished?’), HuffPost, 25 October 2020, https://www.huffingtonpost.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=102081 (last accessed 07 November 2022).

Lee, Jieun & Euisol Jeong (2021), ‘The 4B movement: envisioning a feminist future with/in a non-reproductive future in Korea,’ Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 633-644.

Lim, Jang-won (2021), ‘Kakao TV’s ‘No, Thank You’ rank on Wavve top-10 drama list,’ Korea Herald, 26 January, http://m.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210126000894&a=99 (last accessed 07 November 2022).

Ma, Li (2014), ‘Economic Crisis and Women’s Labor Force Return After Childbirth: Evidence from South Korea,’ Demographic Research, Vol. 31, pp. 511-552.

Ma, Kyoung Hee, Seung-Kyung Kim & Jae Kyung Lee (2016), ‘Work and Family Policy Framing and Gender Equality in South Korea: Focusing on the Roh Moo-huyn and Lee Myung-bak Administrations,’ Development and Society, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 619-652.

Nagtegaal, Jennifer (2021), ‘From “Accidental” Autobiography to Comics Activism: Tracing the Development of an Andalusian-Chinese Feminism in the Work of Comics Artist Quan Zhou,’ in Frederick Luis Aldama (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Gender and Sexuality in Comic Book Studies, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 134-148.

Nam, Jinyoung & Yoonhyuk Jung (2021), ‘‘Digital Natives’ Snack Content Consumption and Their Goals: A Means-End Chain Approach,’ Telematics and Informatics, Vol 63.

Nelson, Laura C. & Haejoang Cho (2016), ‘Women, Gender, and Social Change in South Korea Since 1945’ in Michael J. Seth (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Modern Korean History, London: Routledge, pp. 326- 342.

Oh, David C (2021), ‘‘Feminists Really Are Crazy’: The Isu Station Incident and the Creation of an Androcentric, Misogynistic Community on Youtube,’ Journal of International and Intercultural Communication.

Park, Hyejung (2020), ‘Throwing off the Corset: A Contemporary History of the Beauty Resistance Movement in South Korea,’ Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence, Vol. 5, No. 3.

Pyo, Jane Yeahin, Minji Jang & Tae-Jin Yoon (2020), ‘Dynamics between agents in the new webtoon ecosystem in Korea: Responses to waves of transmedia and transnationalism’ in Dal Yong Jin (ed.), Transmedia Storytelling in East Asia, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 93-110.

Savolainen, Laura, Justus Uitermark & John D Boy (2020), ‘Filtering Feminisms: Emergent Feminist Visibilities on Instagram,’ new media & society, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 557-579.

Sohn, Hee Jeong (2017) Peminijeum ributeu: Hyeomo-ui sidae-reul ttulko naon moksori-deul (Feminism Reboot: The Voices from the Era of Hate) Seoul: Namu Yeonpil, as cited in: Kim, Jinsook (2021), ‘The Resurgence and Popularization of Feminism in South Korea: Key Issues and Challenges for Contemporary Feminist Activism,’ Korea Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4, pp. 75-101.

Song, Jee Eun Regina (2014), ‘The Soybean Paste Girl: The Cultural and Gender Politics of Coffee Consumption in Contemporary South Korea,’ The Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 429-448.

Tréhondart, Nolwenn (2020), ‘When Comics Become ‘Literary Salons’ on Instagram,’ Biens Symboliques / Symbolic Goods, Vol. 7, http://journals.openedition.org/bssg/493 (last accessed 09 November 2022).

Van, Trevor (2020), ‘Instagram Is The New Home Of Webcomics,’ How to Love Webcomics, 13 November 2020, https://www.howtolovecomics.com/2020/11/13/instagram-is-the-new-home-of-webcomics/ (last accessed 11 November 2022).

World Economic Forum (2021), Global Gender Gap Report 2021, March 2021, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf (last accessed 24 August 2022).

Yecies, Brian, Ae-Gyung Shim, Jack (Jie) Yang & Peter Yong Zhong (2020), ‘Global Transcreators and The Extension Of The Korean Webtoon IP-Engine,’ Media, Culture & Society, Vol. 42, Issue 1, pp. 40-57.

Yoon, So-Yeon (2019), ‘Web Comic Captures the Unfair Realities of Married Life: ‘Myeoneuragi’ Resonates With Korean Women Who Face Many Inequalities,’ Korea JoongAng Daily, 21 February 2019, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2019/02/21/features/Web-comic-captures-the-unfair-realities-of-married-life-Myeoneuragi-resonates-with-Korean-women-who-face-many-inequalities/3059686.html (last accessed 26 August 2022).

@aminder_d (2017), ‘#internationalwomensday seems as good a day as any to launch my next comic, this one is called #WomanWorld (more below) […],’ Instagram, 9 March 2017, https://www.instagram.com/p/BRZvWT-Dmug/?hl=en (last accessed 24 August 2022).

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey