‘Misery is actually the only thing interesting’: Happiness Critique in Swedish Feminist Comics

by: Mike Classon Frangos & Maria Margareta Österholm , March 30, 2023

by: Mike Classon Frangos & Maria Margareta Österholm , March 30, 2023

Happiness may be said to be one of the most prominent themes of the feminist boom in Swedish comics since the 1990s. Though Swedish feminist comics have increasingly received scholarly attention in the form of articles on specific creators or trends, the critique of happiness as a feminist concern has not been addressed in detail. [1] This article focuses on representations of ‘bad feelings’ in Swedish feminist comics and graphic novels—including depression, anxiety, narcissism, homesickness, longing, and trauma. We consider how Swedish feminist comics artists explore such psychological and physical states in order to criticise the expectation of happiness associated with neoliberal ideals of the autonomous individual. Examining comics and graphic novels published from the end of the 1990s to the 2020s, we show how an explicitly feminist critique of the promise of happiness emerged in Swedish-language comic art. Though not meant to be exhaustive, our material consists of a broad selection of comics and graphic novels by comics creators who most prominently address the issue of happiness: Johanna Rubin Dranger, Åsa Grennvall, Nina Hemmingsson, Liv Strömquist, Nanna Johansson, Lisa Ewald, Lotta Sjöberg, Edith Hammar, and Bim Eriksson. Drawing on affect studies and queer theory, we read this material in order to trace the development of happiness and its critique as a central preoccupation of Swedish feminist comics in radically different forms and genres.

In The Promise of Happiness, Sara Ahmed identifies what she calls the ‘happiness turn’ (2010: 3) in feminist discourse, an emerging critique of the ‘happiness industry’ of self-help, life coaching, and positive thinking. Happiness discourse is premised on a promise of happiness to those who follow certain life schedules, leading to a situation that Lauren Berlant calls, in the context of neoliberalism, ‘cruel optimism’ (2011: 1), in which an expectation of the good life becomes an obstacle to its own fulfilment. We proceed from Ann Cvetkovich’s analysis of depression as a cultural discourse in her work Depression: A Public Feeling. For Cvetkovich, depression is an example of ‘feeling bad’ (2012: 158) more than a medical diagnosis. She focuses on feminist and queer cultural expressions that point to possibilities of hope beyond the biomedical discourse of mental illness. Cvetkovich writes about what she terms ‘political depression’ (2012: 2) in order to question the focus on the individual in neoliberal discourse as opposed to collective and political issues, calling for ‘embracing rather than glossing over bad feelings’ (2012: 3). Cvetkovich’s understanding of depression as a political emotion works with Ahmed’s feminist critique of the promise of happiness inasmuch as both see feminist potential in alternatives to the happiness scripts of cisheteropatriarchal society.

In Sweden , the critique of the pathologising of femininity through its association with depression can be found in feminist scholarship since the 1970s. In her influential work Den mörka kontintenten [The dark continent], Swedish historian of ideas Karin Johannisson (1994) described the medicalisation of women’s bodies from a feminist perspective, with a focus on the origins of psychoanalysis around the end of the 19th century. In subsequent works, Johannisson would go on to explore how the pathologising of the female body takes place through the proliferation of both historical and current diagnoses from hysteria and hypochondria to paranoia and melancholia. Significantly, Johannisson’s monographs were published by mainstream publishers, reviewed and discussed in major newspapers and radio programs, with a major impact as a public intellectual. During roughly the same period, there emerged a growing debate about consumption in the wake of the turn to neoliberal government after 2006. In 2007, journalist and literary scholar Nina Björk sparked a debate, the so-called ‘Väskdebatten’ [Hand-bag debate], taken up in a number of Swedish newspapers about the new forms of consumerism taking shape at the beginning of the 21st century. Critiques of consumerism are not new in Sweden, but with Björk’s texts, culminating in her book Lyckliga i alla sina dagar [Happily ever after] (2012), this critique began instead to focus on the ideal of the happy and ‘fräsch’ [fresh] individual featured in neoliberal ideology. This concern with happiness under neoliberalism has been a recurring interest in a number of media, including for example journalist and radio host Hanna Hellquist’s popular documentary series from 2011-12 on the search for happiness, and, in the 2020s, Gina Dirawi’s TV series Gina Dirawi lever och dör [Gina Dirawi lives and dies].

In comics scholarship, comics and graphic memoirs particularly about depression have been shown to complicate the neoliberal ideal of the autonomous and independent individual. In her work on graphic narratives about depression, Elisabeth El Refaie (2019: 173) points out the prevalence of ‘fractured’ or ‘split’ selves as visual metaphors. Through their spatial form, comics can visually represent experiences of the splitting of the subject associated with experiences like depression. Not conforming to the expectation of a coherent, individual life story, visual representations of the fracturing of the subject in comics offer a clear contrast to the ideal of the autobiographical subject. As Amelia DeFalco (2015: 224-225) has shown, graphic memoirs can instead lend themselves to representations of care, interdependency and embodiment. In her reading of Ellen Forney and Allie Brosh’s depression comics, Robin Alex McDonald shows how such comics provide ‘alternative anchoring options’ in response to ‘the disorienting, painful, and despairing experience of depression’ (2019: 110). As we will show in this article, comics and graphic novels that represent bad feelings can use these experiences to offer a critique of the neoliberal expectation of happiness and its ideal of the autonomous individual.

Scholarship on Swedish feminist comics has tended to focus on the use of satire and humour in the expression of feminist critique among the most well-known and celebrated Swedish comics artists. In her reading of works by Nina Hemmingsson and Liv Strömquist, Ylva Lindberg argues that both artists use laughter and the grotesque as a form of ‘critical thinking about the world’ (2016: 27). In this context, Lindberg points out especially Hemmingsson’s expressionistic drawing of ‘psychological states’ of ‘contemplation, joy, desire, and tenderness, but also anxiety, sadness, and destructiveness’ (2016: 13-14). The theme of happiness within heteronormative romance and relationships can be traced back to Swedish feminist comics of the 1960s and 1970s, as Nordenstam and Wallin Wictorin have documented (2019: 89-90). Comics that satirise the traditional gender expectations of marriage and family were common in feminist comics anthologies such as Fnitter, for example. In our research on lifelines in Swedish feminist comics, we show how a number of comics artists imagine alternatives to reproductive futurism in the form of a ‘skev’ [skewed] (2021: 32) or fractured relation to heteronormative happiness scripts. Through readings of comics by Liv Strömquist, Karolina Bång, Mats Jonsson, Sofia Olsson, Sara Elgeholm, Linda Spåman, Åsa Grennvall and Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, we focus on representations of having children, or the desire to have or not have children, in which the normative ideal of reproduction is complicated or disrupted. Taking up happiness as a feminist theme, the current article contributes to this emerging scholarship on Swedish feminist comics as a medium for critique and a possibility to imagine alternatives.

To explore the significance of happiness critique in feminist comics, we take up graphic narratives that question the discourse of happiness at different historical moments, through different forms and genres, but sharing a feminist and queer approach. We begin with an overview of the Swedish feminist comics phenomenon since the 1990s through works by Johanna Rubin Dranger, Nina Hemmingsson, Liv Strömquist, Lisa Ewald, Lotta Sjöberg, to document the prevalence of happiness as a feminist issue in this material. We then focus on three examples of Swedish-language comics in different forms and genres, each published roughly 10 years apart, approaching the topic of happiness: Åsa Grennvall’s Mie (2000), Nanna Johannson’s Välkommen till din psykos [Welcome to your psykosis] (2012), and Edith Hammar’s Homo Line (2020). Each example is illustrative of an approach to happiness as a feminist issue in Swedish-language comics in different contexts – the latter of which written and drawn by a Finland-Swedish comics artist and published by a Finnish publisher. Taken together, these comics call into question the individual ego in happiness culture, while pointing to alternatives through their often experimental and playful approaches. The works we analyse by Grennvall, Johansson and Hammar illustrate the splitting of the autonomous, autobiographical subject, expressing experiences of bad feelings and offering alternative versions of happiness from feminist and queer perspectives. Through their different forms and styles, we argue that these works dramatise desires for happiness beyond cisheteronormativity and the neoliberal individual.

The Critique of Happiness in Swedish Feminist Comics

Among Swedish comics artists from the 1990s, Johanna Rubin Dranger is one of a number who treated happiness as a feminist theme. One of her works, Fröken livrädd och kärleken [Miss scaredy-cat and love] (1999), begins with a female figure, who may be a self-representation of the author, in bed next to a man, thinking, ‘Men oj! Vad har hänt? Jag är ju lycklig!’ [Wow, what happened? I’m happy!] (1999: n.p.). In the narrative that follows, the main character’s happiness unravels as she encounters the disappointment that results from the failure of her own expectations of happiness in heteronormative romance. In her next book, Fröken märkvärdrig och karriären [Miss remarkable and her career] (2001), Rubin Dranger depicts feelings of fear and anxiety in the form of a ‘ghost’ or ‘demon’ following her (see Nordenstam & Wallin Wictorin 2021: 25-27). The narrative’s resolution comes with the death of the main character’s ‘storslagna förväntningar’ [grandiose expectations] (2001: n.p.), and the realisation that life continues anyway. Taken together, Rubin Dranger’s works dramatise the promise of happiness and its disappointment in the failure to live up to the expectations of heteronormative patriarchy.

Heteronormative romance and its consequences are also significant themes for two of the most prominent Swedish feminist comics artists: Nina Hemmingsson and Liv Strömquist. Nina Hemmingson’s Jag är din flickvän nu (2006) begins with a single-panel comic in which a female figure wearing a pink dress and pink ribbon in her hair sits with her hands crossed on a table. Below the figure appears the caption text: ‘Men då slog jag näven i bordet och sa till mig själv: hädanefter ska jag fanimej vara lycklig. Och kan man tänka sig, det har jag varit sedan dess’ [But then I banged my fist down on the table and said to myself: from here on out I’m fucking going to be happy. And can you imagine, I have been since then] (2006: 4). The figure’s face is half-illuminated by candle and half-concealed in a dark shadow that extends across the left half of the panel. The expectation of happiness expressed in Hemmingson’s text contrasts with the ominous shading of the image and the aggressive language of the caption, lending a cruel edge to such promises. Throughout the book, Hemmingson’s distinctively drawn figures respond to and often resist the conventional expectations of happiness associated with heteronormativity. Featuring a dark-haired figure who often appears as a self-representation of the artist, Hemmingson’s Jag är din flickvän uses humorous comics to explore gendered social expectations and their consequences especially for women. Depression is a recurring theme of the book. In one four-panel comic with the title ‘några tecken som kan tyda på depression’ [some signs that can indicate depression] (2006: 24), conventional symbols of happiness—summer, tulips and the summer cabin—are responded to by the dark-haired figure with sardonic incomprehension: ‘Har det varit sommar? Var det nyligen eller?’ [Has it been summer? Was it recently?] (2006: 24).

In her book of satirical comics, Prins Charles känsla (2010), Strömquist takes as her point of departure the famous moment when Prince Charles remarked in an interview, ‘Whatever ‘in love’ means’ in response to the interviewer’s observation that he and Diana appear to be ‘very much in love.’ Strömquist’s comic goes on to explore the unequal expectations of heteronormativity and how the promise of happiness through romance is structured differently for gendered subjects. In examples from Prince Charles to Ingmar Bergman to Whitney Houston, Strömquist illustrates the gendered experiences of love and attachment in a heteropatriarchal society. In Strömquist’s view, love can be considered a secular religion. As she puts it, ‘Både religion och kärlek har ett inneboende löfte om perfekt lycka’ [Both religion and love have an intrinsic promise of perfect happiness] (2010: 79). The promise of happiness through romantic love, according to Strömquist, motivates men and women to commit to relationships based on the demand for sexual ownership, or monogamy, a form of attachment that negatively affects especially women’s future life satisfaction, and is thus a feminist issue.

One comics artist who extends the critique of happiness in an even more overtly political direction is Sara Granér. In her book, Det är bara lite aids (2008), dog-headed figures in white laboratory coats attempt to give advice to patients in acute medical situations using positive thinking. In the scene quoted in the book’s title, a doctor informs a patient, ‘äh det är inte så farligt, det är bara lite aids!’ [Oh, it’s not that bad, it’s just a little AIDS!] (2008: n.p.). In another single-page comic, a bed-ridden figure tells a doctor, ‘Livet är så hemskt’ [Life is so terrible], to which the doctor responds, ‘Ja, men snart är det slut’ [Yes, but soon it’s over] (n.p.). In these examples, Granér develops a critique of neoliberalism’s bureaucratic and rationalising discourse, exemplified in this case by the health care system, which had undergone significant neoliberal reform in Sweden during the period of centre-right government after 2006. [2] In the book’s final two single-panel comics, two figures stand in a desert landscape holding dead children and are told by a figure in a suit, ‘ja, det där är smällar man får ta om man lever i en kapitalistisk världsekonomi’ [That’s just the blows you have to take if you live in a capitalist world economy], and ‘Jag tycker du ska se det som en unmaning!’ [I think you should see it as a challenge!] (n.p.). In Granér’s comics, happiness discourse is clearly associated with a destructive neoliberalism whose consequences are war and death on a global scale.

By the 2010s, happiness critique had become a well-established concern of Swedish feminist comics. Titles of satirical comics such as Det kan alltid bli värre [It can always get worse] by Lotta Sjöberg, Allt kommer bli bra [Everything is going to be alright] and Måste carpa [Gotta seize the day] by Lisa Ewald, demonstrate the recognisability and currency of the theme of happiness. As Maria Margareta Österholm has argued, Ewald uses techniques such as collage to tie together cuteness with aggressivity, looking for example at pages in which ‘twisted versions of self-help’ (2018: 374) are used to emphasise images of grotesque femininity. In comparison to Ewald, Sjöberg uses a distinctive approach of comics craftivism to satirise the instance on happiness in contemporary culture. [3] Sjöberg’s Det kan alltid bli värre focuses explicitly on depression and the expectation of happiness in contemporary society. The book’s opening chapter, ‘Ett lyckligt liv’ [A happy life] begins with a definition of the word ‘lycklig’ [happy], ‘en känsla av att må mycket bra och känna sig tillfreds med sitt liv. Trots att det finns krig, rasism, mobbing, miljöförstöring, kvinnohat, homofobi, riskkapitalister, pedofiler, barnfattigdom, kärnkraftsavfall, barnarbetare, djurplågare, våld, cancer, död, förruttnelse, med mera’ [a feeling of doing very well and feeling satisfied with one’s life. Despite there being war, racism, bullying, environmental destruction, misogyny, homophobia, venture capitalists, pedophiles, child poverty, nuclear waste, child labourers, animal abusers, violence, cancer, death, corruption, and more] (2014, 8). In Sjöberg’s work, happiness as the ultimate form of fulfilment in life sits uneasily with the ongoing injustices of contemporary society.

As we have seen, by the time of Ewald’s and Sjöberg’s works in the 2010s, happiness culture had become widespread concerns of the Swedish feminist comics scene, immediately recognisable as a recurrent target for satire and critique. These comics and graphic novels published since the late-1990s adopt somewhat different approaches to the theme of happiness, but each contribute to a broader discussion of happiness culture and its consequences from a feminist perspective. In what follows, we closely analyse three particular examples of comics in which the critique of happiness is further developed.

Misery & Community in Åsa Grennvall’s Mie

Åsa Grennvall’s graphic novel Mie (2000) is an autofictional narrative focused on the gothic and depressive Åsa who feels like an outsider and realises that the hierarchies that rule high school are just as present during her art education, in which she is in her 3rd year. The first pages of the text show how she is lonely, not comfortable at parties, and does not appreciate the sun like her classmates. In the beginning of her third year, Åsa meets Mie, a first-year student, with whom she immediately feels a strong connection. Åsa and Mie’s sense of community is expressed through gothic subculture and music with black clothes, dyed-black hair, black-painted walls in their studio, and references to well-known goth bands. Already in their first conversation—which takes place on a bench which they have moved into the shade—they progress to more personal matters, with Mie talking about her mother’s alcoholism. At first. Mie thinks she has crossed a line and startled Åsa with her ‘misärhistorier’ [misery stories], but Åsa loves misery stories, she exclaims, saying, ‘Vad bra … misär är ju egentligen det enda som är intressant här i världen’ [Good … Misery is actually the only thing interesting in this world.] (2000: n.p). In the next frame they are silent, looking into each other’s eyes, and in the last frame of the page Åsa rests her head in Mie’s lap and closes her eyes. Mie has one hand on Åsa’s cheek and a cigarette in the other. In contrast to their classmates, Mie and Åsa find community in misery, anxiety, and anger. Letting Åsa and Mie express their feelings together, Grennvall suggests hope, foreshadowing the remainder of the story in which Åsa and Mie explore their feelings of misery together. [4]

The girls’ anxiety is personal but also political, and stems from living in a heteropatriarchal society. At a restaurant they run in to one of Mie’s ex-boyfriends. He is happy to see her, but Mie is uncomfortable, and even more so when he mentions that he is glad to see her eat, since ‘det blev ju inte så mycket av det innan’ [there wasn’t so much of that before] (2000: n.p.). When he leaves Mie has lost her appetite: ‘som han så fint påsken sa hade jag ätstörningar när vi var tillsammans… och jag blir så förbannat han inte fattar att det var p.g.a. honom jag hade det]’ [as he politely mentioned I had eating disorders when we were together… and I get so angry that he does not understand that it was because of him I had them] (2000: n.p.). Åsa tells a similar story about a guy who thought that she was ‘världens ledsnaste’ [the saddest person in the world] (2000: n.p), not understanding that her sadness was caused by his behaviour. Mie exclaims, ‘ibland undrar jag om inte vissa killar får stånd av att man har ångest’ [sometimes I wonder if some guys get a hard on when you have anxiety] (2000: n.p.). The last frame contains Åsa’s and Mie’s silhouettes behind the restaurant window, wondering why they must live with these fellow humans, comforting themselves by saying that they already lived a third of their lives.

In the girls’ discussion of depression and anxiety it is clear they view their experiences as effects of the heteropatriarchal society in which they live. In the next section, taking place the day after, Mie shows up in the studio angry, exclaiming ’jag hatar alla som inte är feminister’ [I hate everyone who is not feminist] (2000: n.p.). She kicks a hole in the wall—the only white wall in the studio, not painted black because Åsa had run out of paint—and then she laughs and asks for a pen. She writes beside the hole: ‘ALLA SOM INTE ÄR FEMINISTERS RÖVHÅL’ [EVERYONE THAT IS NOT FEMINIST’S ASSHOLE] (2000: n.p.), suggesting they can use it to kick at. The black hole in the wall can be interpreted as a visual metaphor that makes negative affect visible on the comics page, drawing attention to and politicising their experiences of sexism. Åsa and Mie’s black hole can also be seen as a work of feminist art within the context of the narrative, placed prominently on the wall of their art studio expressing their experiences of depression and anger as political feelings.

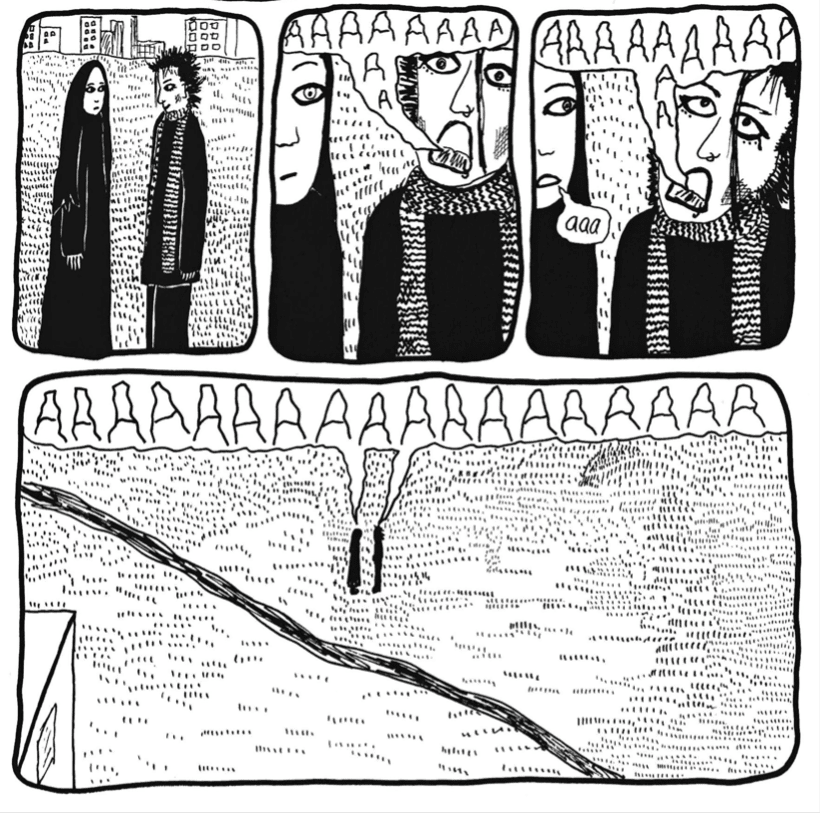

Together Åsa and Mie wonder why they ever engaged in relationships, talk about never feeling present during sex, and the sexual assaults and violence they have experienced. Mie mostly talks about men but mentions that sex with women has been uncomfortable too. [5] Åsa exclaims: ‘Hur FA-AN BLEV JAG HETERO’ [HOW THE HELL DID I BECOME STRAIGHT?] (2000: n.p.). Finally, Mie says that they must stop taking the blame and that it is not their fault, hugging Åsa. On the next page Åsa discloses that the worst of her relationships was with a man who hit her. Mie is shocked and they sit in silence. Åsa is not able to talk about the violence but maybe she should make a graphic novel about it, she says, before acknowledging that she cannot: ‘jag orkar inte’ [I don’t have the energy] (2000: n.p.). [6] Mie takes Åsa by the hand and they walk out on a big empty field. The last frame is of the two of them screaming together and a joint speech bubble filling the upper part of the page and breaking the panel border with a line of fifteen disordered capital A:s. In Mie, there are no words or pictures for Åsa’s experience of trauma, and the comics form itself is destabilised by Mie and Åsa’s scream breaking out of the border of the panel. As El Refaie has discussed (2012: 99-101), trauma in graphic memoirs frequently appears as unrepresentable despite the author’s overt attempts to share the story, with metatextual strategies as a way of pointing to this tension. Similar to the black hole in the wall that Mie paints on the wall of their studio, Mie and Åsa’s screaming in the field offers a way to handle the pain caused by living in a heterosexist society without dismissing or recuperating those feelings, using art and community with others as a tool.

Even though Mie in the story is presented as real person, interacting with, and even seen by people other than Åsa—and is also in conflict with her on one occasion—there are indications that she is in fact just a part of Åsa’s imagination. On the cover their heads are grown together, and on the last page Mie says: ‘Du vet om att jag inte finns på riktigt va?’ You know I don’t really exist, right?’ (2000: n.p.). Åsa responds, ‘Ja, men det gör inget. Du finns för mig,’ followed by, ‘Det här är lite som i Fight Club’ [This is a little like in Fight Club¨ (2000: n.p.). As Nordenstam and Wallin Wictorin point out (2021: 32), the name Mie can also be read as ‘Me,’ implying that the narrator is both characters at the same time. In this interpretation, Mie’s more outspoken behaviour is juxtaposed with Åsa´s melancholy, a way for Grennvall to illustrate different sides of the same character and move beyond realism. However, reading Mie as an imaginary character implies that Åsa has actually been alone through her experience of depression. We suggest a more ambivalent reading wherein Mie also can be understood as a character in her own right in the context of the narrative in which she is seen as interacting with others independent of Åsa. The book’s cover image in which Åsa and Mie are drawn as Siamese twins further highlights the connection and community between the girls. In Mie, Grennvall challenges the limits of the comics form to represent autobiographical experience, gesturing more towards a form of autofiction that blurs the line between autobiographical and fictional representation. [7] In this view, the experiences of sexism, violence, depression, and eating disorders are not individual, but also collective and political, expressed in the form of Åse and Mie’s shared stories and mutual belonging.

Happiness beyond the Self in Nanna Johansson’s Välkommen till din psykos

In the comics collected in Nanna Johansson’s Välkommen till din psykos, the desire for happiness is typically attributed to a subject whose desire resists prevalent social norms. For example, in one single-page comic, a caption reads, ‘Lycka / Att känna håret och pattarna fladdra i vinden’ [Happiness / Feeling your hair and tits flutter in the wind] (2012: 29). Beside the caption, a female figure with blonde hair and pronounced red lipstick stands in profile with four lines representing the wind. The figure’s breasts are drawn as exaggeratedly long, blowing in the same direction as her hair. In another single-page comic, two men with blond hair exclaim, ‘Blondiner har roligare’ [Blondes have more fun] (32). One man is holding a martini glass and the other has his hand on his hip and his leg bent upward, as though dancing. In the foreground of the panel, a brown-haired male figure observes the two blond men with a pronounced frown and a single tear of dismay. Attributing these desires to men who may be interpreted as gay, the comic opens up a queer space of identification in which the refusal of heteronormative gender allows for more fun. Since the expression ‘Blondes have more fun’ is typically used to describe women, the comic also satirises the chauvinist view of female-identified subjects as objects of visual pleasure.

Nanna Johansson’s Välkommen till din psykos is a work of satirical collages consisting mostly of single-panel comics. Though the book is not a graphic memoir, photographs of the author are included in the text to mark divisions between sections, an allusion to the conventions of the graphic memoir in which the author’s photograph is often used to add authenticity to the narrative. [8] However, Johansson’s photographs are marked over with black pen, giving herself mouse whiskers, a moustache, or a Frida Kahlo unibrow. The names for the book’s section divisions are taken from the Freudian terms for the parts of the psyche: ‘superego,’ ‘ego’ and ‘id.’ In this way, the division of Johansson’s Välkommen till din psykos into sections according to the Freudian model of the psyche reflects the splitting or fracturing of the coherent, autonomous subject. The first section, ‘superego,’ takes the form of a letter from Johansson to herself: ‘Hej Nanna! Vad roligt att du/jag ska teckna en ny bok!’ She encourages herself to ‘teckna snyggt’ [draw prettily], ‘gå en liten kvällskurs’ [take an evening course], not to take ‘billiga poänger’ [cheap shots], and not to come across as a ‘dampigt psycho’ [manic psycho] (2012: 6-7). The letter concludes with the exhortation, ‘Gör mig/dig nu inte besviken Nanna. Tänk på alla fina recensioner boken kommer få + Urhunden-priset. Allt går om man bara anstränger sig’ [Don’t disappoint me/yourself Nanna. Think of all the nice reviews your book will get + the Urhunden prize] (7). Johansson’s satirical letter to herself from her ‘superego’ splits the subject into first- and second-person voices, between the superego’s demands and ego’s desire to seek reward and avoid disappointment. Johansson satirises the neoliberal ideal of the autonomous individual by identifying the demand of not being a ‘psycho’ with social norms that the book as a whole cannot live up to, as exemplified by the title, Välkommen till din psykos. Not being a ‘psycho’ is associated with adapting to social norms in terms of also art and writing, norms that are repeatedly challenged in the following sections of the book.

The comics contained in the ‘ego’ section do not contain a narrative of any particular subject so much as they satirise the situation of the ego and its desire in various situations. In one whole-page panel, a woman responds to an ambiguously gendered figure’s request for a place in a lifeboat: ‘Min livscoach har sagt att jag måste bli bättre på att säga ifrån. Så: nej.’ [My life coach has said that I have to get better at speaking up. So: no.] (2012: 12). Another figure in the lifeboat pats the woman on the back and says, in English, ‘Good for you.’ The use of English in the comic associates life-coaching and self-help with transnational, neoliberal discourses in popular culture and media. In this case, life-coaching involves a narcissistic attention to the individual ego at the expense of others. The words of the companion on the lifeboat confirm the woman’s perception of the situation, one in which her own self-definition is more important than a person who risks drowning, a danger that is emphasised by the lightning in the background of the panel. The drowning figure’s question, ‘Finns det plats för en till?’ [Is there room for one more?], contrasts with exaggerated use of space on the life boat to show that there obviously is room for the drowning figure. In this comic, word and image are ironically juxtaposed to call attention to the subject’s insistence on her own desire in the face of social norms.

In the ‘id’ section of Johansson’s book, a long sequence of single-page comics is introduced by a collection of figures including a mushroom and a cupcake gnome with hands and feet, announcing, ‘Välkommen till din psykos!’ [Welcome to your psychosis!] (2012: 91). At one point, in an ink drawing on a pink background, an elderly naked woman exclaims, ‘Kolla! Jag har rakat unibrow på fittan!’ [Look! I’ve shaved a unibrow on my pussy!]. In the foreground, a man gazes up lovingly at the woman, saying, ‘Hon är för rolig, frugan!’ [She’s too funny, the missus!] (116). This single-page comic page shows an ambivalent scene in which a woman invites a man to observe her as she observes herself in the act of observing. The Frida Kahlo unibrow places the comic in the tradition of feminist art history, a satire of the male gaze and the female body as an object of visual pleasure. The man in the comic is shown as enjoying the women’s enjoyment of her own position as both subject and object of the gaze. Since the man’s position of looking is also shared by the reader, we are also drawn into this scenario of visual pleasure that unsettles the distinction between subject and object, observer and observed.

(Un)happy Queers in Edith Hammar’s Homo Line

Finland-Swedish comics artist Edith Hammar’s Homo line is a graphic narrative that poetically explores a longing for something ‘better’ in between the metropoles of Helsinki and Stockholm. Though not a Swedish comics artist, Hammar belongs to the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland, having lived and studied in Stockholm, with comics published primarily in Swedish, and current exhibitions in both Sweden and Finland. For the unnamed, non-binary main character of Homo Line, neither Helsinki nor Stockholm serves as a singular ‘home,’ or object of nostalgic attachment. At the centre of the text is a feeling of ‘hemlängtan’ [homesickness], a longing for home set ambiguously in between Finland and Sweden, the past and the future, reality and the imagination—ultimately taking shape on the Viking Line ferry in transit between the two. The narrative of Homo Line takes place in Helsinki and Stockholm, as well as the space between the two cities on a cruise ship reminiscent of the Viking Line ships—in Hammar’s book transformed into ‘homo line.’ The cruise ship is depicted and alluded to several times, both as a means of transportation between the two cities and as a queer utopia. ‘Min resa går mellan dimension hemlängtan och dimension Viking Line’ [My journey goes between dimension homesickness and dimension Viking Line] (2020: 47). The main character’s moving between cities is pervaded with a feeling of always being out of place, of longing and not belonging. The ferry represents this constant in betweenness, a promise of happiness in the of a ‘bättre’ [better] life that cannot be attained but which continues to inspire the main character’s longing to move in between the cities.

The book’s surrealistic imagery and the narrator’s recounting of dreams and memories makes it difficult to identify any stable time and place for the act of narration. The main character is drawn repeatedly in the form of a giant beside the Viking Line ship, first on the book’s cover and on a number of pages in the beginning, middle and end of the narrative, when the main character is drawn as a giant playing in the water next to (54), riding on top of (107), or submerged up to their face beside (160) the ferry. On one page, the main character is shown sitting alone in the bathtub, playing with a toy version of the ship (12), implying that the entire narrative may occur in the bathtub, and therefore only in their fantasies and memories. In the following pages, the main character is nevertheless shown to rise out of the bathtub and leave the apartment which may or may not be their own, implying actual movement in space and time. As the text explains, ‘Hemlängtan är att lämna, att komma tillbaka, ändå längta, sakna, att sitta fast i en dimension där jag alltid kommer ha hemlängtan’ [Homesickness is to leave, to come back, still long, miss, to be stuck in a dimension where I will always have homesickness, homesickness as chronic condition] (2020: 13-25). Ahmed has pointed out how migration narratives are characterised ‘too many homes and hence no Home, too many places in which memories attach themselves’ (2004: 78), and, in Homo Line it is impossible to determine if the main character’s homesickness refers to Helsinki, Stockholm or both. Instead, each city offers a vision of happiness in the future, a promise of life that may be ‘better’ in an undefined way.

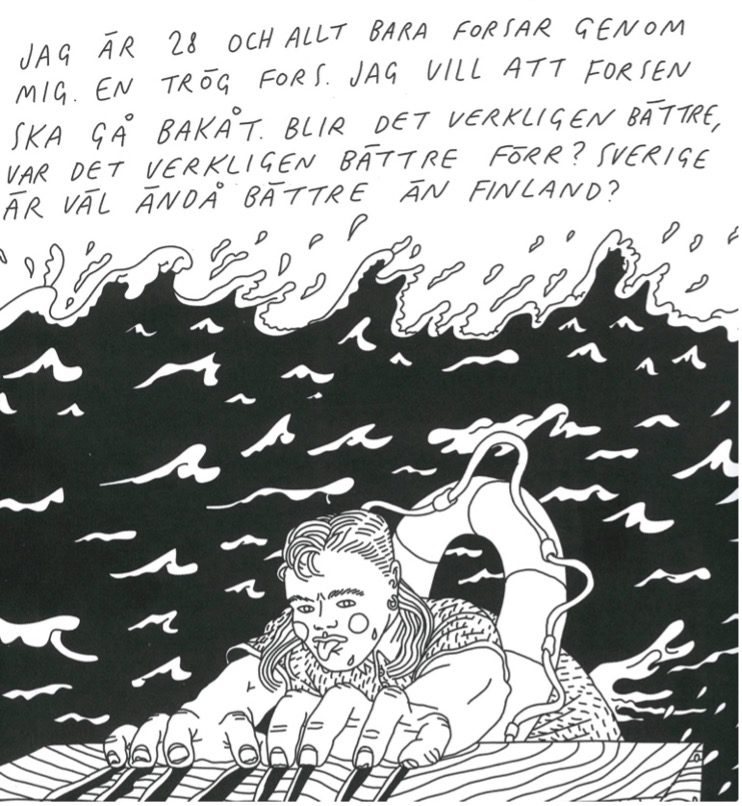

The first urban setting depicted in Homo Line is Helsinki, which is portrayed through an experience of homophobic violence outside a McDonald’s on a central street, Stora Robertsgatan. On the brink of one of many transits from Helsinki to Stockholm, the main character ‘dreams a little’ only to find that ‘när jag vaknar finns där en sexig vegetarisk restaurang, snygga bartenders med ansade skägg och tatueringar som snygga män har… tydligen ett bättre alternativ än mäkken’ [when I wake up there is a sexy vegetarian restaurant, attractive bartenders with trimmed beards and tattoos as attractive men have… apparently, a better alternative than McDonalds] (2020: 40). For the main character, gentrification appears ‘better’ as an ‘alternative’ to homophobia, but this alternative brings with it the logic of the market and the loss of the past. ‘Måste framtiden vara så fräsch och vinstdrivande’ [Must the future be so fresh and profit-driven] (43), asks the main character on the way to the ferry to Stockholm. Much later, the main character mentally compares the gentrification in Helsinki and Stockholm, concluding, ’Här är det ändå samma sak. Helsingfors är också en huvudstad som inte kan värja sig mot gentrifieringen’ [Here it’s still the same thing. Helsinki is also a capital that cannot hold off gentrification] (110). The image of the future as ‘fresh’ or ‘better,’ yet inevitably compromised by neoliberalism, applies both to Helsinki and Stockholm at various points in Homo Line. At one point, the main character reflects, ‘Men ibland är det svårt, just för att framtiden känns så fräsch. Jag känner mig inte så fräsch’ [But sometimes it’s hard, precisely because the future feels so fresh. I don’t feel so fresh] (81). Helsinki and Stockholm each represent the promise of a better alternative while nevertheless failing to deliver on their promise. Later, they continue, ‘Blir det verkligen bättre, var det verkligen bättre förr? Sverige är väl ändå bättre än Finland?’ [Does it actually get better, was it actually better before? I guess Sweden still is better than Finland?] (106).

Throughout the book, the main character is typically depicted alone, in the bathtub, in their apartment, in their cabin on the ferry, or entering the cruise ship by themselves. In one sequence, the main character describes their therapy session, one of the few scenes of connection with another that are not narrated as a dream or fantasy: ‘Jag och min terapeut gick igenom mina olika erfarenheter av våld. Hon berättade att det finns de som menar att det tar sju generationer att komma över krigstrauman’ [My therapist and I went through my different experiences of violence. She said that some people think it takes seven generations to get over war trauma] (2020: 73-74). During their session, the therapist is shown to be writing in her notebook the word ‘homo’ (75), a shortened form of ‘homosexuell’ [homosexual], linking queerness with the main character’s intergenerational trauma. Later in the book, the main character is drawn in a number of erotic encounters taking place ‘i drömversionen av Helsingfors’ [in the dream version of Helsinki] (123), including men in World War II uniforms in various sexual positions. The main character describes telling visitors in Helsinki the story of how Tom of Finland had sex with a man at the Stockman clock, during the blackouts in the Second World War. As Vuorinne and Kauranen (2022) have documented, Homo Line alludes to the recollections of Touko Laaksonen, creator of Tom of Finland, presenting wartime Helsinki as a moment of freedom for queer men, despite homosexuality being illegal in Finland at the time. In Homo Line, the main character wishes they could experience something similar to Laaksonen’s recollection, but not during war, they think in which a sequence in which the main character is drawn with their head in the lap of someone in black jeans, caressing their naked chest. The thought of this hope is written on a buoy floating in the water and attached to their foot with a rope, a fantasy keeping the main character afloat.

José Muñoz (2009) has famously argued that fantasies and longings for a queer past are also a way of imagining a queer future. Muñoz’s queer utopian memory, the desire for what may be, drawing on imaginations of the past, is at play in the final sections of Homo Line, foreshadowing and making possible a queer utopia on the Viking Line in transit between Stockholm and Helsinki. In the book’s final sequence, the pages are turned upside down, revealing a queer utopian community on the Viking Line that can only be seen when read from another perspective. [9] Immediately before the upside-down sequence, the main character is drawn in the form of a giant crying into the sea on which is written the words: ‘Viking Line. Gråt Line. Homo Line.’ [Viking Line. Crying Line. Homo Line.] When the book is turned upside down, a representation of what ‘Homo Line’ could be is revealed. The ship now displays the name Glory, a queer allusion to glory holes, filled with naked and half naked queer people enjoying themselves in swimming pools, information desks, bathrooms, beds and on toy motorcycles—kissing and caressing each other in all corners of the ship. Vuorinne and Kauranen (2022) note that the word ‘homo’ in the book signifies multiple queer sexualities, and in the narrative’s queer utopian ending multiple sexualities are depicted in through a variety of bodies and desires. The main character is part of this queer utopia, glancing at the reader over their shoulder on the final page. Since March 2022 Viking Line actually has a ship called Viking Glory, but in 2020 when Hammar’s book was published, this was still in the future. In Homo Line, the Viking Line of the future becomes a site for imagining a queer utopia in which bad feelings are not disavowed in the search for a ‘better’ or ‘fresher’ option, but explored and embraced as a strategy for keeping the queer utopia afloat.

Conclusion

Muñoz has famously suggested that queerness can be understood as something not yet here, something that ‘does not yet exist, but can be glimpsed if we ‘squint’ and ‘strain our vision’ to ‘see otherwise’ (2009: 22). This form of squinting and seeing otherwise is a central feature of Homo Line, and its utopian imagining of the queer, and indeed, of much of the material we have considered. This can be viewed as a reparative strategy, not glossing over bad feelings, but transforming them to keep the queer utopia afloat, as in the Viking Line Glory imagined on the horizon of the future in Homo Line.

Another significant example of queer speculative comics about happiness is Bim Eriksson’s Baby Blue (2021). In a future Sweden, a fascist regime is introduced to maintain social order through the elimination of antinormative feelings, forbidding, for example, music, public displays, and Google searches about depression. Eriksson’s dystopian narrative draws on the well-established critique of happiness discourse in Swedish feminist comics to show how neoliberal ideology depends on the disavowal of bad feelings that trouble the ideal of the autonomous individual. Within the dystopia depicted in Baby Blue, an alternative, queer utopia emerges located in the forest outside the city, a refuge for the queer subjects who do not conform to the norms of the dominant society. Here too, queer utopia becomes a matter of form, as the contrast between the two spaces is signaled through the use of minimalistic drawing and white space for the city, a thinly veiled version of Stockholm, and the queer utopia outside the city, drawn with detailed, intricate backgrounds. Through the dystopia of Baby Blue is not overturned at the end of the narrative, the main characters continue their ‘motståndsrörelsen’ [resistance movement] (2021: 259), driving off in their classic car for the refuge of the queer utopia.

As we have seen, the critique of happiness is a prominent theme of Swedish feminist comics. The promise of happiness, as Ahmed has shown, has been associated with the ideal of the ‘happy housewife,’ and a critique of this image has been central within feminist discourse since the 1950s. Happiness as an expectation within heteronormative romance has been a recurring theme for a number of Swedish feminist comics artists, including some of the most well-known and established. By the 2010s, in the wake of neoliberal government in Sweden, the ideal of the happy and ‘fresh’ individual of neoliberal ideology came under increasing critique from a feminist perspective. In Swedish feminist comics, as well as feminist and queer theory, the neoliberal happiness industry is critiqued for its view of happiness as an individual rather than a political issue. In this article, we have analysed happiness and its critique in a broad selection of comics and graphic novels in a variety of forms and genres, with close analysis of works by Åsa Grennvall, Nanna Johansson, and Edith Hammar. As we have argued, Swedish feminist comics frequently criticise neoliberal and cisheternormative discourses of individual happiness through the representations of bad feelings and the imagining of queer alternatives.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Swedish Research Council project Contemporary Swedish Feminist Comics as Medium for Political Activism and Critique, VR2018-01165.

Notes

[1] Swedish feminist comics research has by this point become too large to summarise, but we are especially indebted to articles by Nordenstam & Wallin Wictorin (2017, 2019, 2021, 2022) which provide an important foundation in the field. See also Lindberg (2016), Österholm (2018), and Frangos (2020).

[2] Nordenstam and Wallin Wictorin (2017) describe the political context for the rise of Swedish feminist comics in terms of the reaction to the neoliberal reforms of the centre-right government after 2006.

[3] Nordenstam and Wallin Wictorin (2022) have called attention to Sjöberg’s ‘craftivist’ technique, using digital images of embroidered fabrics to place her satirical comics in a feminist art tradition.

[4] The beginning of Mie and Åsa’s relationship also foreshadows the many misery stories to come in Grennvall’s later autofictional works (see Nordenstam & Wallin Wictorin 2021, Österholm 2022).

[5] Though much of Åsa and Mie’s dialogue concerns heterosexual relationships, their relationship is also intimate and physical from the start. Through much of the book they also discuss prominent subcultural men such as Trent Reznor and Daniel Ash, a conversation that oscillates between identification, attraction, and dreams of belonging, which we suggest can also be read as a queer identification beyond the gender binary.

[6] Grennvall’s next book Sjunde våningen [Seventh Floor] actually tells this story (see Nordenstam & Wallin Wictorin 2021).

[7] See Ernst (2017, 79-85) for a discussion of Grennvall’s works in terms of autobiography and autofiction. The use of fictional devices and different names for the main characters (only sometimes the same as the author) complicates any reading of Grennvall’s works as straightforwardly autobiographical.

[8] On the use of photographs in some prominent Swedish graphic memoirs, see Ernst 2015.

[9] Vuorinne and Kauranen (2022) read the upside-down pages in Homo Line as a kind of epilogue. An analysis of upside-down pages in comics would be beyond the scope of this article, but compare for example the upside-down pages in Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara (2004), The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ahmed, Sara (2010), The Promise of Happiness, Durham: Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren (2011), Cruel Optimism, Durham: Duke University Press.

Björk, Nina (2012), Lyckliga i alla sina dagar: om pengars och människors värde, Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.

Cvetkovich, Ann (2012), Depression: A Public Feeling, Durham: Duke University Press.

DeFalco, Amelia (2018), ‘Graphic Somatography: Life Writing, Comics, and the Ethics of Care,’ Journal of Medical Humanities, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 223-240.

El Refaie, Elisabeth (2012), Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

El Refaie, Elisabeth (2019), Visual Metaphor and Embodiment in Graphic Illness Narratives, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eriksson, Bim (2021), Baby Blue, Stockholm: Galago.

Ernst, Nina (2015), ‘Photographs in Graphic Memoirs by Jonsson and Moissenen,’ Image & Narrative, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 65-83.

Ernst, Nina (2017), Att teckna sitt jag. Grafiska självbiografier i Sverige, Malmö: Apart förlag.

Ewald, Lisa (2013), Allt kommer bli bra, Stockholm: Galago.

Frangos, Mike Classon (2020), ‘Liv Strömquist’s Fruit of Knowledge and the Gender of Comics,’ European Comic Art, Vol. 13, No.1, pp. 45-69.

Frangos, Mike Classon & Maria Margareta Österholm (2021), ’När ska du ha barn? Skeva livslinjer i svenska feministiska serieböcker,’ Tidskrift för genusvetenskap,Vol. 42, No. 2-3, pp. 27-48.

Granér, Sara (2008), Det är bara lite aids, Stockholm: Galago.

Grennvall, Åsa (2000), Mie, Göteborg: Optimal Press.

Hammar, Edith (2020), Homo Line, Helsinki: Förlaget.

Hemmingsson, Nina (2006), Jag är din flickvän nu, Stockholm: Kartago.

Johannisson, Karin (1994), Den mörka kontinenten: kvinnan, medicinen och fin-de-siècle, Stockholm: Norstedt.

Nanna Johansson (2012), Väkommen till din psykos, Stockholm: Galago.

Lindberg, Ylva (2016), ‘The Power of Laughter to Change the World: Swedish Female Cartoonists Raise Their Voices,’ Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 3-31.

McDonald, Robin Alex (2019), ‘Comics, Corn, and the Queer Phenomenology of Depression,’ Literature and Medicine, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 96-112.

Nordenstam, Anna & Margareta Wallin Wictorin (2017), ‘The Future in Swedish Avant-Garde Comics 2006-2014’ in Francesco-Alessio Ursini, Adnan Mahmutović & Frank Bramlett (eds), Visions of the Future in Comics: International Perspectives, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, pp. 211-228.

Nordenstam, Anna & Margareta Wallin Wictorin (2019), ‘Women’s liberation. Swedish feminist comics and cartoons,’ European Comic Art, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 77-105.

Nordenstam, Anna & Margareta Wallin Wictorin (2021), ’Swedish feminist comics and cartoons at the turn of the millennium: Joanna Rubin Dranger & Åsa Grennvall’ in Kristy Beers Fägersten, Anna Nordenstam, Leena Romu, & Margareta Wallin Wictorin (eds), Comic Art and Feminism in the Baltic Sea Region: Transnational Perspectives. New York: Routledge, pp. 17-39.

Nordenstam, Anna & Margareta Wallin Wictorin (2022) ‘Comics Craftivism: Embroidery in Contemporary Swedish Feminist Comics,’ Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 174-192.

Muñoz, José (2009), Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York: New York University Press.

Rubin Dranger, Joanna (1999), Fröken Livrädd & kärleken, Stockholm: Bonnier.

Sjöberg, Lotta (2014), Det kan alltid bli värre, Stockholm: Galago.

Strömquist, Liv (2010), Prins Charles känsla, Stockholm: Galago.

Vuorinne, Anna & Ralf Kauranen (2022), ‘Visions of Queer Places: Migration and Utopia in Finnish Queer Comics,’ European Comic Art, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 26-45.

Österholm, Maria Margareta (2018), ‘Rainbow Coloured Dots and Rebellious Old Ladies. The Gurlesque in Two Contemporary Swedish Comic Books,’ European Journal of Women’s Studies: Femininity Revisited: Figuring Critical Femininity Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 371-383.

Österholm, Maria Margareta (2022), ‘The Pain and the Creeping Feeling: Skewed Girlhood in Two Graphic Novels by Åsa

WHO SUPPORTS US

The team of MAI supporters and contributors is always expanding. We’re honoured to have a specialist collective of editors, whose enthusiasm & talent gave birth to MAI.

However, to turn our MAI dream into reality, we also relied on assistance from high-quality experts in web design, development and photography. Here we’d like to acknowledge their hard work and commitment to the feminist cause. Our feminist ‘thank you’ goes to:

Dots+Circles – a digital agency determined to make a difference, who’ve designed and built our MAI website. Their continuous support became a digital catalyst to our idealistic project.

Guy Martin – an award-winning and widely published British photographer who’s kindly agreed to share his images with our readers

Chandler Jernigan – a talented young American photographer whose portraits hugely enriched the visuals of MAI website

Matt Gillespie – a gifted professional British photographer who with no hesitation gave us permission to use some of his work

Julia Carbonell – an emerging Spanish photographer whose sharp outlook at contemporary women grasped our feminist attention

Ana Pedreira – a self-taught Portuguese photographer whose imagery from women protests beams with feminist aura

And other photographers whose images have been reproduced here: Cezanne Ali, Les Anderson, Mike Wilson, Annie Spratt, Cristian Newman, Peter Hershey